History of Ireland facts for kids

The story of humans in Ireland began about 33,000 years ago. More signs of early people have been found from around 10,500 to 8,000 BC. After the ice melted around 9700 BC, the Stone Age started. This included the Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age), Neolithic (New Stone Age) from about 4000 BC, and the Copper Age around 2500 BC. The Bronze Age began around 2000 BC, followed by the Iron Age around 600 BC with the arrival of the Celts.

Ancient Greek and Roman writers wrote a little about Ireland during this time. By the late 300s AD, Christianity slowly started to replace the old Celtic religions. By the end of the 500s, writing was introduced, and a strong Christian church changed Irish society a lot.

From the late 700s AD, Vikings from Norway started raiding and settling in Ireland. This led to new ideas and changes in how people fought and traveled. Many of Ireland's towns, like Dublin, started as Viking trading posts. Coins also appeared for the first time. The Vikings didn't take over all of Ireland, and their power lessened after the Battle of Clontarf in 1014.

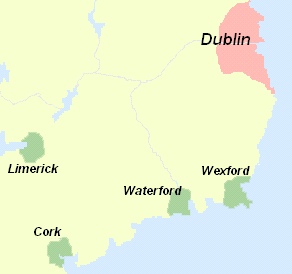

In 1169, the Normans arrived, leading to English involvement in Ireland for over 800 years. At first, the Normans gained a lot of land. But over time, the native Irish fought back and regained control of most of the country, except for walled towns and the area around Dublin called The Pale.

The English Crown didn't try to fully conquer Ireland again until the early 1500s. It was a slow and costly process because Ireland was divided into many small areas, and the people were strong fighters. The Irish also resisted the new Protestant faith. This led to the Tudor conquest of Ireland, which lasted from 1534 to 1603. Henry VIII declared himself King of Ireland in 1541.

Ireland became a battleground in the religious wars between Catholic and Protestant Europe. England tried to control or change both the old Norman-Irish lords and the native Irish areas. This caused many wars, like the Desmond Rebellions and the Nine Years War. During this time, thousands of English and Scottish Protestant settlers arrived, taking land from the native Catholic landowners. Gaelic Ireland was finally defeated at the battle of Kinsale in 1601. This marked the end of the old Gaelic system and the start of Ireland becoming part of the English, and later, British Empire.

In the 1600s, the split between the Protestant landowners and the Catholic majority grew stronger. This conflict became a major part of Irish history. Protestant control was made stronger after two religious wars: the Irish Confederate Wars (1641-52) and the Williamite War (1689–91). After this, political power was mostly held by a small group of Protestants. Catholics and other Protestant groups faced harsh rules called the Penal Laws.

On January 1, 1801, after the United Irishmen Rebellion, the Irish Parliament was closed. Ireland became part of the new United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Catholics didn't get full rights until 1829, thanks to Daniel O'Connell. The terrible Great Famine hit Ireland in 1845. Over a million people died from hunger and disease, and another million left the country, mostly for America.

Irish people continued to seek independence. Charles Stewart Parnell's Irish Parliamentary Party tried to get Home Rule (self-government) from the 1880s. They finally won the Home Rule Act 1914, but it was put on hold when World War I started.

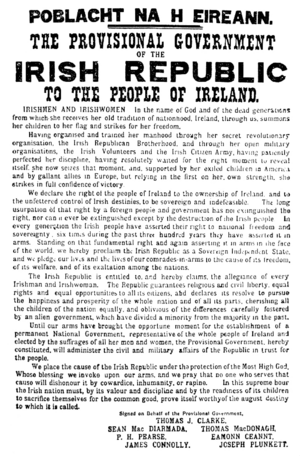

In 1916, the Easter Rising in Dublin turned public opinion against British rule. In 1922, after the Irish War of Independence, most of Ireland left the United Kingdom to become the independent Irish Free State. However, six counties in the northeast, known as Northern Ireland, remained part of the UK. This created the partition of Ireland. The treaty that caused this split led to the Irish Civil War, which the "pro-treaty" forces won.

The history of Northern Ireland has been shaped by the division between (mostly Catholic) Irish nationalists and (mostly Protestant) British unionists. These differences led to the Troubles in the late 1960s. Violence continued for 28 years until the Good Friday Agreement in 1998 brought a difficult but mostly successful peace.

Contents

- Ancient Ireland (10,500 BC–400 AD)

- Early Christian Ireland (400–800)

- Early Medieval and Viking Era (800–1166)

- Norman Ireland (1168–1535)

- Early Modern Ireland (1536–1691)

- Protestant Control (1691–1801)

- Union with Great Britain (1801–1912)

- Home Rule, Easter Rising, and War of Independence (1912–1922)

- Free State and Republic (1922–present)

- Northern Ireland (1921–present)

- Modern Ireland

- Flags in Ireland

- Images for kids

- See also

Ancient Ireland (10,500 BC–400 AD)

What we know about Ireland before Christianity comes from Roman writings, Irish poems, myths, and archaeology. Some very old tools have been found, but it's not certain if people lived in Ireland during the earliest Stone Age. However, a bear bone found in 1903 with cut marks from stone tools suggests humans might have been in Ireland as early as 10,500 BC.

From Stone Age to Bronze Age

The first confirmed people in Ireland were Mesolithic hunter-gatherers. They arrived after 8000 BCE when the climate became warmer. Ireland was separated from Great Britain by water around 14,000 BC. These people remained hunter-gatherers until about 6000 BCE.

Around this time, the world's first signs of complex farming appeared with the discovery of the Céide Fields. This led to a rich Neolithic culture. People started making pottery, polished stone tools, and rectangular wooden houses. They also built huge stone tombs for their communities, called megalithic tombs. Some of these, like Newgrange, are massive stone monuments and are lined up with the sun or stars.

The Bronze Age began in Ireland around 2000 BC. During this time, people made beautiful gold and bronze jewelry, weapons, and tools. Instead of large communal tombs, people started burying their dead in smaller stone boxes or simple pits. These could be in cemeteries or under circular mounds of earth or stone.

Iron Age

The Iron Age in Ireland started around 600 BC. During this period, small groups of Celtic-speaking people slowly moved into Ireland. Celtic styles from Europe, like the La Tene style, appeared in the north of the island by 300 BC. Over time, the blending of Celtic and native cultures led to the rise of Gaelic culture by the 400s AD.

By the 400s, important kingdoms began to form in Ireland. These kingdoms had a rich culture. Society was led by powerful warriors and learned people, possibly including Druids.

Linguists realized that the language spoken by these people, called Goidelic languages, was a branch of the Celtic languages. Some believe this happened because Celts invaded from Europe. However, other research suggests that the culture developed slowly. Celtic language and ideas might have come from trading with Celtic groups in Europe from the Stone Age to the Bronze Age.

The Romans called Ireland Hibernia. Ptolemy wrote about Ireland's geography and tribes in 100 AD. Ireland was never part of the Roman Empire, but Roman influence reached beyond its borders. Some experts think Roman-backed Irish forces might have even invaded Britain around 100 AD.

Irish groups, called the Scoti, attacked and settled in Great Britain around 367 AD. For example, the Dál Riata settled in western Scotland.

Early Christian Ireland (400–800)

The middle centuries of the first millennium AD saw big changes in Ireland. The old tribal system was replaced by ruling families by the 700s. Irish pirates raided the coast of western Britain, similar to how the Vikings would later attack Ireland. Some of these pirates even started new kingdoms in Scotland and parts of Wales.

It's thought that some of these returning Irish people, perhaps as rich traders or slaves, first brought Christianity to Ireland. Some early stories say missionaries were active in southern Ireland long before St. Patrick.

Tradition says that in 432 AD, St. Patrick arrived and worked to convert the Irish to Christianity. His own writing, Confession, is the earliest Irish historical document. It tells us a little about him. However, another writer, Prosper of Aquitaine, said that Palladius was sent to Ireland by the Pope in 431 as "first Bishop to the Irish believing in Christ." This shows there were already Christians in Ireland. Palladius seems to have worked with existing Christians, while Patrick, who might have arrived later, focused on converting the pagan Irish in other areas.

Patrick is often given credit for keeping and organizing Irish laws, changing only those that went against Christian ways. He is also said to have brought the Latin alphabet, which helped Irish monks write down old oral stories. However, historians still debate how much of this is true. The "myth of Patrick" developed centuries after his death.

Irish scholars became very good at studying Latin and Christian ideas in the monasteries that grew quickly. Missionaries from Ireland traveled to England and Europe, spreading news of this learning. Scholars from other countries came to Irish monasteries. These monasteries helped keep Latin learning alive during the Early Middle Ages.

This period saw a flourishing of Insular art, especially in illuminated manuscripts (decorated books), metalwork, and sculptures. Famous examples include the Book of Kells, the Ardagh Chalice, and the many carved stone crosses around the island.

The first English involvement in Ireland happened during this time. English students came to Ireland to study or live in places like Tullylease and Maigh Eo na Saxain, founded by 670. In 684, an English army from Northumbria raided Brega in Ireland.

Early Medieval and Viking Era (800–1166)

The first recorded Viking raid in Ireland happened in 795 AD when Vikings from Norway looted the island. These early raids were usually quick and small. They interrupted the golden age of Christian Irish culture and started two centuries of fighting. Vikings plundered monasteries and towns across Ireland. Most of these early raiders came from western Norway.

The Vikings were skilled sailors. By the early 840s AD, they began to set up settlements along the Irish coasts and stay through the winter. Vikings founded towns in several places, most famously in Dublin. Records from this time show that Vikings moved inland to attack, often using rivers, before returning to their coastal bases.

In 852 AD, Vikings landed in Dublin Bay and built a fortress. After a few generations, a group of mixed Irish and Norse people emerged, called the Gall-Gaels (Gall means foreign in Old Irish).

In 902 AD, the Irish king Muirecán pushed the Vikings out of Ireland. They were allowed to settle in England but later returned to retake Dublin.

However, the Vikings never fully controlled Ireland. They often fought for or against different Irish kings. The Battle of Clontarf in 1014 marked the start of the decline of Viking power in Ireland. But the towns they founded continued to grow, and trade became an important part of the Irish economy.

Norman Ireland (1168–1535)

Arrival of the Normans

By the 1100s, Ireland was divided into many small kingdoms. Powerful families fought for control over the whole island. One of these kings, Diarmait Mac Murchada of Leinster, was forced out by the new High King, Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair. Diarmait went to France and got permission from King Henry II to recruit Norman knights to help him get his kingdom back.

The first Norman knight landed in Ireland in 1167. More Normans, Welsh, and Flemish fighters followed. Diarmait regained some of his lands and named his son-in-law, the Norman Richard de Clare (known as Strongbow), as his heir. This worried King Henry II, who feared a rival Norman state in Ireland. So, he decided to take control himself.

With permission from Pope Adrian IV, King Henry landed in Waterford in 1171. He was the first English King to come to Ireland. Henry gave his Irish lands to his younger son John, calling him "Lord of Ireland." When John later became King of England, the "Lordship of Ireland" came directly under the English Crown.

Lordship of Ireland

The Normans first controlled the entire east coast, from Waterford to eastern Ulster, and moved far inland. King John, the first Lord of Ireland, visited in 1185 and 1210. He helped strengthen the Norman-controlled areas and made Irish kings promise loyalty to him.

Throughout the 1200s, English Kings tried to weaken the power of the Norman lords in Ireland. The Norman-Irish community faced challenges that stopped their expansion.

Gaelic Comeback and Norman Decline

By 1261, the Normans were clearly weakening. Fineen MacCarthy defeated a Norman army at the Battle of Callann. Wars continued between different lords for about 100 years, causing much destruction, especially around Dublin. In this chaos, local Irish lords won back large amounts of land they had lost.

The Black Death arrived in Ireland in 1348. It hit the English and Norman people harder because they lived mostly in towns. The native Irish, who lived in spread-out rural areas, were less affected. After the plague passed, the Irish language and customs became dominant again. The English-controlled area shrank to a fortified region around Dublin, known as the Pale. Outside this area, English authority was very weak.

By the end of the 1400s, central English power in Ireland had almost disappeared. England was busy with its own wars. The Lordship of Ireland was controlled by the powerful Fitzgerald Earl of Kildare family. They ruled the country using military force and alliances with Irish lords. Local Irish lords grew more powerful, but the Dublin government's power was limited by Poynings' Law in 1494. This law put the Irish Parliament under the control of the English Parliament.

Early Modern Ireland (1536–1691)

Conquest and Rebellions

From 1536, Henry VIII decided to conquer Ireland and bring it under his control. The Fitzgerald family, who had been the real rulers of Ireland, had become unreliable. They had even supported a rival to the English throne in 1487. In 1536, Silken Thomas Fitzgerald openly rebelled against the King.

After putting down this rebellion, Henry decided to bring Ireland under full English government control. He didn't want Ireland to be a base for future rebellions or foreign invasions of England. In 1541, he changed Ireland from a lordship to a full Kingdom of Ireland. Henry was declared King of Ireland by the Irish Parliament that year. This was the first time Gaelic Irish chiefs and Norman-Irish nobles attended the Parliament together.

The next step was to extend the English Kingdom of Ireland's control over all its claimed territory. This took almost a century, with English leaders either negotiating or fighting with the independent Irish and Old English lords. The Spanish Armada in Ireland suffered heavy losses in storms in 1588.

The conquest was finished during the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I of England, after several harsh conflicts. After this, English authorities in Dublin finally had real control over Ireland. They brought a central government to the whole island and disarmed the native lords. However, the English failed to convert the Catholic Irish to Protestantism. The brutal methods used by the English, including using military law, increased anger against English rule.

From the mid-1500s to the early 1600s, the government carried out a policy called Plantations. Scottish and English Protestant settlers were sent to parts of Ireland, like Munster and Ulster. These Protestant settlers replaced the Irish Catholic landowners who were removed from their lands. These settlers formed the ruling class in future British governments in Ireland. Several Penal Laws were introduced to encourage Catholics to convert to the official Church of Ireland.

Wars and Penal Laws

The 1600s were very bloody in Ireland. Two periods of war (1641–53 and 1689–91) caused huge loss of life. Most of the Irish Catholic landowners lost their land, and Catholics were put under the harsh Penal Laws.

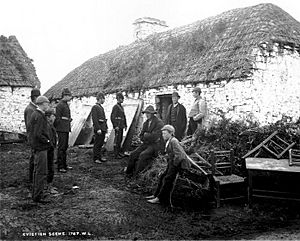

During the 1600s, Ireland was torn apart by eleven years of warfare. It began with the Irish Rebellion of 1641, when Irish Catholics rebelled against the control of English and Protestant settlers. The Catholic gentry briefly ruled the country as Confederate Ireland (1642–1649). Then, Oliver Cromwell reconquered Ireland from 1649–1653 for the English government. Cromwell's conquest was the most brutal part of the war. By the end, up to a third of Ireland's population was dead or had left the country. As punishment for the 1641 rebellion, the best lands owned by Irish Catholics were taken and given to British settlers.

Ireland became a main battleground after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 in England. The Catholic James II left London, and the English Parliament replaced him with William of Orange. Wealthy Irish Catholics supported James to try to reverse the Penal Laws and get their land back. Protestants supported William and Mary to keep their property. James and William fought for Ireland in the Williamite War, most famously at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, where James's forces were defeated.

Forced Labor

From the 1400s to the 1700s, Irish, English, Scots, and Welsh prisoners were sent to the Caribbean for forced labor. Even more people came voluntarily as servants who worked for a set time. In the 1700s, they were sent to the American colonies, and in the early 1800s, to Australia. The English often described the Irish as "savages," which made it seem okay to take their land. In 1654, the British parliament allowed Oliver Cromwell to banish Irish "undesirables." Cromwell gathered Catholics and sent them on ships to the Caribbean, especially Barbados. By 1655, 12,000 political prisoners had been forced into servitude there.

Protestant Control (1691–1801)

Most people in Ireland were Catholic farmers. They were very poor and had little political power in the 1700s. Many of their leaders became Protestant to avoid harsh economic and political punishments. However, a Catholic cultural awakening was growing.

There were two Protestant groups. Presbyterians in Ulster in the North lived better economically but had almost no political power. Power was held by a small group of Anglo-Irish families who were loyal to the Anglican Church of Ireland. They owned most of the farmland, where Catholic farmers did the work. Many of these families lived in England and were absentee landlords. The Anglo-Irish who lived in Ireland increasingly saw themselves as Irish nationalists. They were unhappy with English control of their island. Their spokesmen, like Jonathan Swift, wanted more local control.

Irish resistance ended after the Battle of Aughrim in July 1691. The Penal Laws were made even stricter after this war. The Anglo-Irish ruling class wanted to make sure Irish Catholics couldn't rebel again. Power was held by the 5% of the population who were Protestants belonging to the Church of Ireland. They controlled all major parts of the Irish economy, most of the farmland, the legal system, and local government. They also had strong majorities in both houses of the Irish Parliament. They didn't trust the Presbyterians in Ulster and believed Catholics should have very few rights. They didn't have full political control because the government in London had higher authority.

Irish anger towards England grew because of Ireland's economic situation in the 1700s. Some absentee landlords managed their lands poorly. Food was often grown for export rather than for people in Ireland to eat. Two very cold winters led to a famine between 1740 and 1741. This killed about 400,000 people and caused over 150,000 Irish to leave the island. Also, Irish exports were limited by laws that put taxes on Irish products entering England. Despite this, most of the 1700s were peaceful compared to the previous centuries, and the population doubled to over four million.

By the 1700s, the Anglo-Irish ruling class saw Ireland, not England, as their home country. A group in Parliament, led by Henry Grattan, pushed for better trade with Great Britain and more independence for the Irish Parliament. However, reforms stalled over giving Irish Catholics full voting rights. This was partly allowed in 1793, but Catholics still couldn't become members of the Irish Parliament or government officials. Some people were inspired by the French Revolution of 1789.

Presbyterians also faced some unfair treatment. In 1791, a group of Protestants, mostly Presbyterians, formed the Society of the United Irishmen. At first, they wanted to reform the Irish Parliament, allow Catholics to vote, and remove religion from politics. When their goals seemed impossible, they decided to use force to overthrow British rule and create a non-religious republic. Their efforts led to the Irish rebellion of 1798, which was brutally put down.

Ireland was a separate kingdom ruled by King George III of Britain. He set policy for Ireland through his appointed representative, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. In practice, the representatives often lived in England, and Irish affairs were largely controlled by an elite group of Irish Protestants. This changed in 1767 with the appointment of a strong English representative, George Townshend. He had the support of the King and the British government, so most major decisions were made in London. The ruling class complained and got new laws in the 1780s that made the Irish Parliament more effective and independent of the British Parliament, though still under the King's control.

Mostly because of the 1798 rebellion, Irish self-government ended completely with the Acts of Union 1800.

Union with Great Britain (1801–1912)

In 1800, after the Irish rebellion of 1798, the British and Irish parliaments passed the Acts of Union 1800. This created a new country called the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland starting January 1, 1801. Part of the agreement was that laws discriminating against Roman Catholics and other Protestant groups would be removed. However, King George III blocked these attempts.

In 1823, a Catholic lawyer named Daniel O'Connell, known as 'The Liberator', started a successful campaign for Catholic rights. This led to the Catholic Relief Act 1829, which allowed Catholics to sit in Parliament. O'Connell later led a campaign to undo the Act of Union, but it was unsuccessful.

The second of Ireland's "Great Famines," An Gorta Mór, hit the country from 1845–49. A disease affecting potatoes, along with political factors, led to widespread starvation and people leaving the country. The population dropped from over 8 million before the Famine to 4.4 million in 1911. The Irish language, once widely spoken, sharply declined after the Famine and with the new education system. English largely replaced it.

Outside of mainstream nationalism, there were several violent rebellions by Irish republicans. These included one in 1803 led by Robert Emmet, a rebellion in 1848 by the Young Irelanders, and another in 1867 by the Irish Republican Brotherhood. All of them failed, but the idea of using force for independence remained.

The late 1800s saw major land reforms. The Irish National Land League demanded "Fair rent, free sale, fixity of tenure" for farmers. Parliament passed laws that allowed most tenant farmers to buy their lands and lowered rents for others. These laws effectively ended the era of the absentee landlord and solved the "Irish Land Question."

In the 1870s, the issue of Irish self-government became a major topic again under Charles Stewart Parnell. He founded the Irish Parliamentary Party. Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone tried twice to pass Home Rule (self-government) laws, in 1886 and 1893, but failed. Parnell's leadership ended when he was involved in a scandal and died in 1891.

After a law in 1898 gave local control to elected councils, the debate over full Home Rule led to tensions. Irish nationalists wanted self-government, while Irish unionists (who wanted to stay with the UK) feared losing power. Most of the island was nationalist, Catholic, and farming-based. The northeast, however, was mostly unionist, Protestant, and industrial. Unionists worried about losing political and economic power in a Catholic home-rule state. Nationalists believed they would remain second-class citizens without self-government. This division led to two opposing groups: the Protestant Orange Order and the Catholic Ancient Order of Hibernians.

Home Rule, Easter Rising, and War of Independence (1912–1922)

Home Rule seemed certain in 1910 when the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) held the balance of power in the British Parliament. The third Home Rule Bill was introduced in 1912. Unionists immediately resisted, forming the Ulster Volunteers. In response, the Irish Volunteers were created to support Home Rule.

In September 1914, as World War I began, the UK Parliament passed the Home Rule Act 1914. It was put on hold for the war. To ensure Home Rule after the war, nationalist leaders supported Ireland's involvement in the British war effort. The core of the Irish Volunteers opposed this, but most left to form the National Volunteers and joined Irish regiments in the British Army. Before the war ended, Britain tried twice to implement Home Rule, but the Irish sides couldn't agree on terms for Ulster.

The period from 1916–1921 was marked by political violence. It ended with the partition of Ireland and independence for 26 of its 32 counties. A failed attempt to gain full independence was the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin. Support for the rebels was small at first, but the harsh way it was put down increased support for them. Also, the threat of Irishmen being forced to join the British Army in 1918 sped up this change. In the December 1918 elections, Sinn Féin, the rebels' party, won three-quarters of all seats in Ireland. Twenty-seven of their elected members met in Dublin on January 21, 1919, to form a 32-county Irish Republic Parliament, the first Dáil Éireann. They declared independence for the entire island.

Unwilling to negotiate anything less than full independence, the Irish Republican Army (IRA), the army of the new Irish Republic, fought a guerilla war (the Irish War of Independence) from 1919 to 1921. During the fighting, the Government of Ireland Act 1920 implemented Home Rule while dividing the island into "Northern Ireland" and "Southern Ireland".

In July 1921, the Irish and British governments agreed to a truce. In December 1921, representatives signed an Anglo-Irish Treaty. This ended the Irish Republic and created the Irish Free State, a self-governing area like Canada. Under the Treaty, Northern Ireland could choose to stay in the United Kingdom, which it quickly did. In 1922, both parliaments approved the Treaty. This made the 26-county Irish Free State independent (it later renamed itself Ireland in 1937 and became a republic in 1949). The 6-county Northern Ireland gained Home Rule but remained part of the United Kingdom. For most of the next 75 years, each area was strongly linked to either Catholic or Protestant ideas, especially in Northern Ireland.

Free State and Republic (1922–present)

The treaty that divided Ireland also split the republican movement. Some were "anti-Treaty" (they wanted to keep fighting for a full Irish Republic). Others were "pro-Treaty" (they accepted the Free State as a first step to full independence). From 1922 to 1923, both sides fought the bloody Irish Civil War. The new Irish Free State government defeated the anti-Treaty part of the Irish Republican Army. This division among nationalists still affects Irish politics today.

The new Irish Free State (1922–37) existed during a time when dictatorships were growing in Europe and there was a major world economic downturn. Unlike many European countries, it remained a democracy. The losing side in the Civil War, Éamon de Valera's Fianna Fáil party, was able to take power peacefully by winning the 1932 election. This showed that they finally accepted the Free State. The Free State remained financially stable due to low government spending, despite an "Economic War" with Britain. However, unemployment and emigration were high. The population dropped to a low of 2.7 million in 1961.

With the partition of Ireland in 1922, 92.6% of the Free State's population was Catholic, and 7.4% was Protestant. By the 1960s, the Protestant population had halved. Many Protestants left in the early 1920s because they felt unwelcome in a mostly Catholic state. Some feared violence, and others saw themselves as British and didn't want to live in an independent Irish state. The Catholic Church also had a rule that children of Catholic-Protestant marriages had to be raised Catholic. After 1945, the rate of Protestant emigration fell.

In 1937, a new Constitution renamed the state Ireland (or Éire in Irish). The state remained neutral during World War II, which saved it from much of the war's horrors. However, there were food and coal shortages. Although officially neutral, recent studies suggest Ireland helped the Allies more than was known, even providing secret weather information for D-Day.

In 1949, the state was formally declared a republic and left the British Commonwealth of Nations.

In the 1960s, Ireland saw big economic changes under Prime Minister Seán Lemass. Free secondary education was introduced in 1968. From the early 1960s, Ireland wanted to join the European Economic Community. It joined in 1973, at the same time as the UK.

Global economic problems in the 1970s, along with some poor economic policies, caused the Irish economy to slow down. The Troubles in Northern Ireland also discouraged foreign investment. In 1979, the Irish Pound became a separate currency, breaking its link with the UK's currency. However, economic reforms in the late 1980s, helped by money from the European Union, led to one of the world's highest economic growth rates. This period was known as the Celtic Tiger.

Ireland's prosperity ended suddenly in 2008 when the banking system collapsed. A huge amount of money was needed to save failing Irish banks. This led to a major financial and political crisis, and Ireland entered a recession. Emigration rose, and unemployment increased.

However, since 2014, Ireland has seen strong economic growth, sometimes called the "Celtic Phoenix."

Northern Ireland (1921–present)

"A Protestant State" (1921–1972)

The 1920 Government of Ireland Bill created Northern Ireland, made up of six northeastern counties. From 1921 to 1972, Northern Ireland was governed by a Unionist government. Its first Prime Minister, James Craig, said it would be "a Protestant State for a Protestant People." This was to ensure a Unionist majority. The Ulster Unionist Party formed every government until 1972.

There was discrimination against the minority nationalist (Catholic) community in jobs and housing. They were also largely excluded from political power. This led to the creation of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association in the late 1960s. This group was inspired by Martin Luther King's civil rights movement in the USA.

The military groups of Northern Protestants and Catholics (IRA) turned to violence. After World War II, keeping peace within Northern Ireland seemed impossible. Economic pressures, stronger Catholic unity, and British involvement led to the collapse of the government. As the civil rights movement in the US gained attention, Catholics in Northern Ireland rallied for similar rights. This led to groups like the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) in 1967. Peaceful protests became important for gaining support.

However, these protests caused problems for Northern Ireland's Prime Minister, Terence O'Neill. He was trying to convince Catholics that they belonged in the United Kingdom. Despite O'Neill's efforts, there was growing unhappiness among both Catholics and Unionists. In October 1968, a peaceful civil rights march in Derry turned violent when police beat protesters. This was shown on international TV, highlighting the conflict in Ireland. A violent reaction from conservative unionists led to civil disorder. To restore order, British troops were sent to Northern Ireland.

The violence in the late 1960s helped strengthen military groups like the IRA. They presented themselves as protectors of working-class Catholics. Recruitment into the IRA increased as violence worsened. British troops were not enough to stop the violence. On January 30, 1972, tensions exploded on "Bloody Sunday." British paratroopers opened fire on civil rights protesters in Derry, killing 13 unarmed civilians. "Bloody Friday" and other violent acts in the early 1970s became known as the Troubles.

The Northern Ireland Parliament was suspended in 1972 and abolished in 1973. Private armies like the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) and the Ulster Volunteer Force fought each other. The British Army and the (mostly Protestant) Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) were also involved. This chaos led to the deaths of over 3,000 people, including civilians and military personnel. Most of the violence was in Northern Ireland, but some spread to England and across the Irish border.

Direct Rule (1972–1999)

For the next 27 and a half years, Northern Ireland was under "direct rule" from London. A British government minister was in charge of Northern Ireland's government departments. Direct Rule was meant to be temporary until Northern Ireland could govern itself again.

Attempts were made to create a power-sharing government, with both nationalist and unionist communities involved. The Northern Ireland Constitution Act 1973 and the Sunningdale Agreement in December 1973 tried this. These acts did little to create unity between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. The 1973 Act said that Ireland could only be reunified if the people of Northern Ireland (and the Republic) agreed. The Sunningdale Agreement brought together political leaders from Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland, and the UK for the first time since 1925. However, all these attempts failed to reach agreement or last long.

In the 1970s, British policy focused on defeating the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) militarily. Although IRA violence decreased, it was clear that a military victory wasn't possible. Even Catholics who didn't support the IRA were unwilling to support a state that seemed to have discrimination. Unionists were not interested in Catholic involvement in running the state.

In the 1980s, the IRA tried to win a decisive military victory with large arms shipments. When this failed, senior republican figures began to look for other ways to achieve their goals, moving towards ending military action. In 1986, the British and Irish governments signed the Anglo Irish Agreement. This showed a formal partnership in finding a political solution. The agreement recognized the Irish government's right to be consulted and guaranteed equal treatment and recognition of Irish and British identities. It also called for cross-border cooperation.

Socially and economically, Northern Ireland had the highest unemployment in the UK. Although public spending helped modernize services and move towards equality, progress was slow in the 1970s and 1980s. Only in the 1990s, when peace became more likely, did the economic situation improve. By then, the population of Northern Ireland had changed significantly, with more than 40% being Catholic.

Devolution and Direct Rule (1999–present)

More recently, the Belfast Agreement (also called the "Good Friday Agreement") on April 10, 1998, brought some power-sharing to Northern Ireland. From December 2, 1999, both unionists and nationalists gained control of limited areas of government. However, the power-sharing government and elected Assembly were suspended several times. This happened due to a lack of trust between political parties over issues like paramilitary weapons, police reform, and removing British Army bases.

In new elections in 2003, the more moderate parties lost ground to the more hard-line Democratic Unionist Party (unionist) and Sinn Féin (nationalist) parties. On July 28, 2005, the Provisional IRA announced the end of its armed campaign. On September 25, 2005, international inspectors confirmed the IRA had fully disarmed. Finally, power-sharing was restored in April 2007.

Modern Ireland

Ireland's economy became more varied and advanced than ever before by joining the global economy. By the early 1990s, Ireland had become a modern industrial economy. It created a lot of national income that helped the whole country. Although farming was still important, Ireland's industries made advanced goods that competed internationally. Ireland's economic boom in the 1990s was called the Celtic Tiger.

The Catholic Church, which once had great power, found its influence on social and political issues in Ireland much reduced. Irish bishops could no longer easily tell people how to vote. Modern Ireland's separation of the Church from everyday life can be explained by younger generations losing interest in Church teachings. Also, there were questions about the actions of some Church representatives. Many in Ireland began to doubt the Church's trustworthiness. In 2011, Ireland closed its embassy at the Vatican, which seemed to be a result of this trend.

Flags in Ireland

The national flag of Ireland is a flag with three colors: green, white, and orange. The green stands for Roman Catholics, the orange for Protestants, and the white for the hoped-for peace between them. This flag dates back to the mid-1800s.

The flag was first shown in public by Young Irelander Thomas Francis Meagher. He explained its meaning: "The white in the center means a lasting peace between the 'Orange' (Protestants) and the 'Green' (Catholics). I hope that under this flag, Irish Protestants and Irish Catholics can join hands in friendship." Another nationalist, John Mitchel, said, "I hope to see that flag one day waving as our national banner."

After it was used in the 1916 Rising, it became widely accepted by nationalists as the national flag. It was used officially by the Irish Republic (1919–21) and the Irish Free State (1922–37).

In 1937, when the Constitution of Ireland was introduced, the tricolour was officially confirmed as the national flag. While it is the official flag of Ireland today, it is not an official flag in Northern Ireland, though it is sometimes used unofficially there.

The only official flag representing Northern Ireland is the Union Flag of the United Kingdom. However, its use is sometimes debated. The Ulster Banner is sometimes used unofficially as a regional flag for Northern Ireland.

Since the partition of Ireland, there has been no single flag accepted by everyone to represent the entire island. For some sports events, the Flag of the Four Provinces is sometimes used and is generally accepted.

Historically, several flags have been used, including:

- Saint Patrick's Flag (St Patrick's Saltire, St Patrick's Cross), which represented Ireland on the Union Flag after the Act of Union.

- A green flag with a harp (used by most nationalists in the 1800s, also the flag of Leinster).

- A blue flag with a harp (used from the 1700s onwards by many nationalists, now the flag of the President of Ireland).

- The Irish tricolour.

St Patrick's Saltire was once used to represent the island of Ireland by the all-island Irish Rugby Football Union (IRFU), before they started using the four-provinces flag. The Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) uses the tricolour to represent the whole island.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Irlanda para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Irlanda para niños