Food in ancient Rome facts for kids

Food and dining in the Roman Empire were shaped by the many different foods available through their huge trade networks. They also kept old traditions from ancient Rome, partly learned from the Greeks and Etruscans. Roman dinner parties, called convivium, focused mainly on food. Big feasts were also a key part of Roman religion.

Making sure the city of Rome had enough food became a big political issue. Roman emperors used food supply as a way to show their care for the people. Roman food sellers and farmers' markets offered meats, fish, cheeses, fresh produce, olive oil, and spices. You could also find prepared food at pubs, bars, inns, and food stalls.

Bread was a very important part of the Roman diet. Wealthier people ate wheat bread, while poorer people ate bread made from barley. Fresh produce like vegetables and beans were also important, as farming was highly valued. Romans ate many kinds of olives and nuts. Even though some important Romans didn't like eating meat, many meat products were prepared, including sausages, cured ham, and bacon.

People thought goat or sheep milk was better than cow's milk. Milk was often made into cheese, which was a good way to store and trade it. While olive oil was essential for Roman cooking, butter was seen as a strange food from Gaul. Sweet foods like pastries usually used honey and wine-must syrup for sweetness. Romans also ate many dried fruits (like figs, dates, and plums) and fresh berries.

Salt was a basic seasoning, but pure salt was expensive. The most common salty sauce was garum, a fermented fish sauce. Local seasonings included garden herbs, cumin, coriander, and juniper berries. Imported spices included pepper, saffron, cinnamon, and fennel. Wine was an important drink, but Romans didn't like drinking too much. They usually mixed their wine with water, as drinking it "straight" was seen as a barbarian custom.

Contents

Roman Food Basics

The main ingredients in Roman dishes were wheat, wine, meat, fish, bread, and various sauces and spices. Wealthy Romans often lived luxurious lives and sometimes hosted large banquets or feasts.

Grains and Legumes

Most people got at least 70% of their daily energy from cereals and legumes (like beans and peas). Grains included different types of wheat such as emmer, rivet wheat, einkorn, spelt, and common wheat. Less popular grains were barley, millet, and oats.

Legumes included lentils, chickpeas, bitter vetch, broad beans, garden peas, and grass peas. Farmers often planted legumes in rotation with cereals to help enrich the soil. Legumes were also stored in case of food shortages. Even though they were usually simple food, legumes also appeared in dishes at fancy banquets.

Puls, a type of pottage (thick soup or porridge), was considered the very first food of the Romans. It was used in some old religious ceremonies that continued during the Empire. This basic grain porridge could be made more interesting with chopped vegetables, small pieces of meat, cheese, or herbs. This made dishes similar to polenta or risotto.

People living in cities and soldiers preferred to eat their grain as bread. Poorer people ate coarse brown bread made from emmer or barley. Fine white loaves were made light and fluffy using yeast or sourdough cultures. The Celts in Spain and Gaul, who drank beer, were known for their excellent breads made with barm (a type of yeast from brewing). A poem called Moretum describes a "ploughman's lunch": a flatbread cooked on a griddle, topped with cheese and a pesto-like sauce, similar to pizza or focaccia.

Having a bread oven was a lot of work and needed space. So, people living in apartment buildings probably prepared their dough at home and then took it to a shared oven to be baked. Mills and bakeries were so important to Rome's well-being that several religious festivals honored the gods who helped with these processes. Even the donkeys that worked in the mills were honored.

Other Produce

Because owning land was so important to Roman leaders, Romans were very proud of serving produce (fruits and vegetables). Leafy greens and herbs were eaten as salads with vinegar dressing. Cooked vegetables like beets, leeks, and gourds were prepared with sauces as first courses or served with bread as a simple meal. The Romans had over 20 types of vegetables and greens. Cured olives were available in many varieties, even for those with less money. Truffles and wild mushrooms, though not eaten every day, were probably gathered more often than they are today.

Roman provinces exported regional dried fruits like figs from Caria and dates from Thebes. Fruit trees from the East were also grown throughout the Western Empire. These included cherries from Pontus (modern-day Turkey), peaches from Persia (Iran), along with lemons and other citrus fruits. Apricots came from Armenia. The "Damascan" or damson plum came from Syria. What Romans called the "Punic apple" was the pomegranate from North Africa. Romans ate cherries, blackberries, currants, elderberries, dates, pomegranates, peaches, apricots, quinces, melons, plums, figs, grapes, apples, and pears.

Berries were grown or gathered wild. Common nuts included almonds, hazelnuts, walnuts, pistachios, pine nuts, and chestnuts. Fruit and nut trees could be grafted to grow many different varieties on one tree.

Meat and Dairy

Even though some important Romans, like Emperors Didius Julianus and Septimius Severus, didn't like meat, Roman butchers sold many kinds of fresh meats. These included pork, beef, and mutton or lamb. Because there was no refrigeration, Romans developed ways to preserve meat, fish, and dairy. No part of an animal was wasted. This led to dishes like blood puddings, meatballs (called isicia), sausages, and stews. People in the countryside cured ham and bacon. Regional specialties, like the fine salted hams from Gaul, were traded. Sausages from Lucania were made from a mix of ground meats, herbs, and nuts, with eggs to bind them. They were then aged in a smoker.

Fresh milk was used in medicines, beauty products, or for cooking. People thought goat or sheep milk was better than cow's milk. Cheese was easier to store and transport to market. Old writings describe how cheese was made, including fresh and hard cheeses, regional types, and smoked cheeses.

Oils and Fats

Olive oil was essential not just for cooking, but for the Roman way of life. It was also used in lamps and for bathing and grooming. The Romans invented the trapetum to press olive oil. The olive groves in Roman Africa were very productive, with trees larger than those in Mediterranean Europe. Large lever presses were developed to extract the oil efficiently. Spain was also a major exporter of olive oil, but Romans thought oil from central Italy was the best.

Butter was mostly disliked by the Romans, but it was a key part of the Gallic diet. Lard (pig fat) was used for baking pastries and seasoning some dishes.

Seasonings and Sweeteners

Salt was the most basic seasoning. Pliny the Elder said that "Civilized life cannot proceed without salt." It was an important trade item, but pure salt was quite expensive. The most common salty sauce was garum, a fermented fish sauce that added a savory flavor, now called "umami". Major producers of garum were in the provinces of Spain.

Local seasonings included garden herbs, cumin, coriander, and juniper berries. Pepper was so important that special ornamental pots (called piperatoria) were made to hold it. Piper longum was imported from India, as was spikenard, used to season game birds and sea urchins.

Other imported spices included saffron, cinnamon, and silphium from Cyrene. This was a strong type of fennel that was over-harvested and became extinct during Emperor Nero's rule. After that, it was replaced with laserpicium, which was asafoetida imported from modern-day Afghanistan. Pliny estimated that Romans spent a huge amount of money each year on spices and perfumes from India, China, and the Arabian peninsula.

Sweeteners were mostly limited to honey and wine-must syrup (called defrutum). Cane sugar was an exotic ingredient used as a garnish, a flavoring, or in medicines.

Farming and Markets

The Roman government actively supported farming. Producing food was the top priority for land use. Larger farms, called latifundia, were very efficient. They helped feed the cities and allowed people to have more specialized jobs. The Empire's network of roads and shipping lines helped small farmers by giving them access to local and regional markets in towns. Farming techniques like crop rotation and selective breeding were shared across the Empire. New crops, like peas and cabbage, were brought to places like Britain.

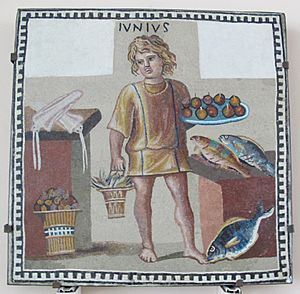

Art from across the Empire shows food sellers. In the city of Rome, the Forum Holitorium was an old farmers' market, and the Vicus Tuscus was known for its fresh produce. Throughout the city, meats, fish, cheeses, produce, olive oil, spices, and the common sauce garum (fish sauce) were sold at macella, which were Roman indoor markets, and at marketplaces in the provinces.

The Annona (Food Supply System)

Making sure the city of Rome had an affordable food supply became a big political issue in the late Republic. The government started giving out grain (called the annona) to citizens who signed up for it. About 200,000–250,000 adult men in Rome received this handout. Each person got about 33 kg (73 lbs) of wheat per month. This meant about 100,000 tons of wheat per year, mainly from Sicily, North Africa, and Egypt.

This food handout cost at least 34% of the government's income. However, it improved living conditions for poorer Romans. It also helped the rich by allowing workers to spend more of their money on wine and olive oil, which were produced on the estates of wealthy landowners.

The grain handout also had a special meaning. It showed the emperor as a generous helper and confirmed that all citizens had a right to share in "the fruits of conquest." The annona, public buildings, and exciting shows helped make life better for lower-class Romans and kept social unrest down. However, the writer Juvenal saw "bread and circuses" (panem et circenses) as a sign that Romans had lost their political freedom. He wrote: The public has long since cast off its cares: the people that once bestowed commands, consulships, legions and all else, now meddles no more and longs eagerly for just two things: bread and circuses.

Romans who received the grain took it to a mill to be ground into flour. By the time of Emperor Aurelian, the government started giving out the annona as a daily ration of bread baked in state factories. They also added olive oil, wine, and pork to the handout.

Eating Out and Prepared Food

Most people in the city of Rome lived in apartment buildings (called insulae) that did not have kitchens. Sometimes, shared cooking areas might be available on the ground floor. A charcoal brazier (a portable heater) could be used for simple cooking like grilling or stewing in a pot (olla). However, these were fire hazards and didn't have good ventilation.

Prepared food was sold at pubs, bars, inns, and food stalls (called tabernae, cauponae, popinae). Some places had counters with openings for pots. These might have kept food warm over a heat source (a thermopolium) or simply served as storage vessels (dolia).

Carryout food and restaurant dining were mostly for the lower classes. Going to taverns was sometimes seen as a moral failing, and emperors or public figures might be criticized for it. Mills and commercial ovens were usually found together in bakery complexes.

Menus and Recipes

The Latin saying for a full-course dinner was ab ovo usque ad mala, meaning "from the egg to the apples." This is like the English phrase "from soup to nuts." A multi-course dinner started with the gustatio ("tasting" or "appetizer"). This was often a salad or a simple dish meant to help digestion. The main meal, called cena, focused on meat. This was a tradition from communal feasts that followed animal sacrifices. A meal ended with fruits and nuts, or with extra desserts (secundae mensae).

Roman writings mostly describe the dining habits of the upper classes. The most famous description of a Roman meal is probably Trimalchio's dinner party in the Satyricon. This was a fictional, over-the-top feast that was not like real life, even for the very rich. The poet Martial describes a more realistic dinner. It began with the gustatio, which was a salad made of mallow leaves, lettuce, chopped leeks, mint, arugula, and mackerel with rue. It also had sliced eggs and marinated sow udder. The main course was tender cuts of kid meat, beans, greens, a chicken, and leftover ham. Dessert was fresh fruit and old wine.

Roman books about farming include a few recipes. A whole collection of Roman recipes is linked to Apicius, a name for several famous "gourmets" from ancient times. The recipes are written like notes from a chef to a colleague, often without exact measurements. However, Apicius uses eight different verbs for how to use eggs in a dish, including one that might describe making a soufflé.

Recipes included regional specialties like Ofellas Ostiensis. This was an hors d'oeuvre made from "choice squares of marinated pork cooked in a spicy sauce with typical Roman flavors: lovage, fennel, cumin, and anise." A special dish called Patina Apiciana needed a complex forcemeat (ground meat mixture) layered with egg and crepes, served on a silver platter.

Roman "foodies" enjoyed wild game, fowl like peacock and flamingo, large fish (especially prized mullet), and shellfish. Oysters were farmed at Baiae, a resort town known for a regional shellfish stew. This stew was made from oysters, mussels, sea urchins, celery, and coriander.

Emperor Vitellius's most amazing dish was supposedly the "Shield of Minerva". It was made of pike liver, brains of pheasant and peacock, flamingo tongue, and lamprey milt. The historian Suetonius emphasized that these expensive ingredients came from far parts of the empire, from the Parthian border to the Straits of Gibraltar. The historian Livy connected the rise of gourmet cooking to Roman expansion. He said the first chefs arrived in 187 BC, after the Galatian War.

Wine and Other Drinks

Even though food shortages were a constant worry, Italian viticulture (grape growing) produced a lot of cheap wine that was sent to Rome. Most provinces could make wine, but regional types were popular, and wine was a key trade item. It was rare for there to be a shortage of everyday wine. Regional wines like Alban, Caecuban, and Falernian were highly valued. Opimian was the most famous and expensive wine.

The main suppliers for Rome were the west coast of Italy, southern Gaul, the Tarraconensis region of Spain, and Crete. Alexandria, the second-largest city in the Empire, imported wine from Laodicea in Syria and the Aegean Sea. In shops, taverns, or special wine shops (vinaria), wine was sold by the jug to take home or by the drink to have there. Prices varied based on quality.

Besides drinking wine with meals, it was also part of daily religious practices. Before a meal, a libation (a drink poured as an offering) was made to the household gods. When Romans visited burial sites to care for the dead, they poured a libation. Some tombs even had a tube for pouring into the grave.

Romans drank their wine mixed with water, or in "mixed drinks" with flavorings. Mulsum was a sweet mulled wine. Apsinthium was a wormwood-flavored drink, similar to absinthe. Even though wine was enjoyed regularly, drinking too much of it was looked down upon. The Gauls also brewed different kinds of beer.

Dining at Home

Since restaurants served the lower classes, fine dining could only be found at private dinner parties in wealthy homes or at banquets hosted by social clubs (collegia). The private home (domus) of a rich family would have had a kitchen, a kitchen garden, and a trained staff. This staff included a chef (archimagirus), a sous chef (vicarius supra cocos), and kitchen assistants (coci).

In upper-class homes, the evening meal (cena) was very important for social gatherings. Guests were entertained in a beautifully decorated dining room (triclinium), often with a view of the garden. Diners relaxed on couches, leaning on their left elbow. The perfect number of guests for a dinner party (convivium, meaning "living together") was nine.

By the late Republic, if not earlier, women dined, reclined, and drank wine along with men. Sometimes, children also attended so they could learn social skills. Multi-course meals were served by household slaves, who are often shown in art from that time as symbols of hospitality and luxury.

Feeding the Military

One of the main challenges for the Roman military was feeding the soldiers, cavalry horses, and pack animals (usually mules). Wheat and barley were the main food sources. Meat, olive oil, wine, and vinegar were also provided. An army of 40,000 people, including soldiers and others like slaves, would have about 4,000 horses and 3,500 pack animals. An army this size would eat about 60 tons of grain and drink 240 large jars (amphorae) of wine and olive oil every day.

Each man received about 830 grams (1.8 pounds) of unmilled wheat per day. Unmilled grain lasted longer than flour. Handmills were used to grind it. The supply of all these foods depended on what was available and was hard to guarantee during wars or bad conditions. The military attracted sutlers (vendors) who sold various items, including food, which soldiers could buy to add to their diet.

During the Republic's expansion, the army usually combined living off the land (finding food locally) with organized supply lines (the frumentatio) to get its food. Under the Empire, provinces sometimes paid taxes in the form of grain to supply the permanent military bases.

Cultural Views on Food

Fancy cooking could be seen as a sign of either civilized progress or a decline into luxury. The early Imperial historian Tacitus compared the rich foods of Roman tables in his time with the simple diet of the Germanic peoples. The Germanic people ate fresh wild meat, gathered fruit, and cheese, without imported spices or complex sauces.

Because owning land was so important in Roman culture, produce—cereals, legumes, vegetables, and fruit—was often considered a more civilized food than meat. The Stoic philosopher Musonius Rufus, who was a vegetarian, believed that meat-eaters were not only less civilized but also "slower in intellect."

"Barbarians" were sometimes stereotyped as very hungry meat-eaters. The Historia Augusta describes emperors Didius Julianus and Septimius Severus as disliking meat and preferring vegetables. However, the first emperor born of two barbarian parents, Maximinus Thrax, was said to have eaten huge amounts of meat.

For Pliny, making pastries was a sign of civilized countries at peace. The basic Mediterranean staples of bread, wine, and oil became sacred in Roman Christianity. Meanwhile, Germanic meat eating became a sign of paganism, as it might have come from animal sacrifice.

Some philosophers and Christians resisted the body's desires and the pleasures of food. They adopted fasting as an ideal. Food generally became simpler as city life in the West declined, trade routes were disrupted, and the rich moved to their country estates where they had to be more self-sufficient. As city life became linked with luxury, the Church officially discouraged gluttony. Hunting and pastoralism (herding animals) were seen as simple but good ways of life.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |