History of education facts for kids

The history of education shows how learning has changed over thousands of years, starting from the very first written records of ancient civilizations. It covers almost every country and how they taught their people.

Contents

- Education in Ancient Times

- Formal Education in the Middle Ages (500–1500 AD)

- Education After the 15th Century

- Recent World-Wide Trends

- See also

Education in Ancient Times

The very first known formal school was set up in ancient Egypt during the Middle Kingdom. It was led by Kheti, who was the treasurer for Mentuhotep II (around 2061-2010 BC).

In Mesopotamia, learning to write the early cuneiform script was very hard and took many years. Because of this, only a few people became scribes and learned to read and write. Usually, only the children of kings, rich families, or important professionals like scribes and doctors went to school. Most boys learned their father's job or became apprentices to learn a trade. Girls stayed home to learn housekeeping and cooking from their mothers. Later, when writing became simpler, more people in Mesopotamia learned to read and write. In Babylon, most towns and temples had libraries. An old saying from Sumer was: "He who would excel in the school of the scribes must rise with the dawn." Scribes became an important group in society, working in farming, as personal assistants, or even as lawyers. Both men and women learned to read and write. For the Babylonians, this also meant knowing the old Sumerian language. They even had special books like dictionaries and grammar guides for students. Huge collections of texts have been found from Old Babylonian scribal schools called edubas (2000–1600 BCE), which helped spread reading and writing. The Epic of Gilgamesh, a famous poem from Ancient Mesopotamia, is one of the earliest known stories.

Ashurbanipal (685 – c. 627 BC), a king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, was very proud of his education. When he was young, he studied things like mathematics, reading, and writing, along with horse riding, hunting, and being a good soldier. During his time as king, he collected many clay tablets with writing from all over Mesopotamia, especially Babylonia. He kept them in the Library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh. This was the first library in the ancient Middle East that was organized in a proper way, and parts of it still exist today.

In ancient Egypt, only a small group of educated scribes could read and write. Only people from certain families were allowed to train as scribes, working for temples, the pharaoh, or the army. The hieroglyph system was always hard to learn, but later it was made even harder on purpose. This helped scribes keep their special status. It's hard to know exactly how many people could read and write in ancient Egypt. Estimates range from 1% to 5% of the population, but some think it might have been higher in cities.

In ancient Israel, the Torah (a main religious text) tells people to read, learn, teach, and write it. This meant that reading and studying were very important. In 64 AD, the high priest made sure schools were opened. Students focused on having good memory skills and understanding what they learned by saying it out loud many times. Girls didn't go to formal schools, but they needed to know a lot to manage a home after marriage and teach their young children. Even with this system, it seems many children didn't learn to read and write. Some guess that only about 3% of Jewish people in Roman Palestine could read and write well.

In the Islamic world, which spread from China to Spain between the 7th and 19th centuries, schooling began in 622 AD in Medina, Saudi Arabia. At first, lessons were held in mosques. Later, separate schools were built next to mosques. The first separate school was the Nizamiyah school, built in 1066 in Baghdad. Children started school at age six with free lessons. The Quran encourages Muslims to get an education, so schools became common in ancient Muslim societies. Muslims also had one of the first universities in history, Al-Qarawiyyin University in Fez, Morocco. It started as a mosque built in 859.

Education in India

In ancient India, education was mostly given through the Vedic and Buddhist systems. Sanskrit was used for Vedic education, and Pali for Buddhist education. In the Vedic system, children started school between ages 8 and 12, while in the Buddhist system, they started at age eight. The main goals of education in ancient India were to build a person's character, teach self-control, raise social awareness, and keep ancient culture alive.

The Vedic system taught the four Vedas (Rig Veda, Sama Veda, Yajur Veda, Atharva Veda) and six Vedangas (like grammar and astronomy).

Vedic Education

In ancient India, knowledge was passed down by speaking, not writing. Education had three steps:

- Shravana: Learning by listening to holy texts.

- Manana: Thinking about, analyzing, and understanding what was heard.

- Nididhyāsana: Using that knowledge in real life.

During the Vedic period (around 1500 BC to 600 BC), most education was based on the Vedas and later Hindu texts. The main goal of Vedic education was spiritual freedom. It included learning how to say the Vedas correctly, rules for rituals, grammar, writing, and understanding nature. Some medical knowledge was also taught, including herbal medicines.

Women's education was important in ancient India. They learned dance, music, and housekeeping. Some women, called Sadyodwahas, were educated until they married. Others, called Brahmavadinis, never married and studied their whole lives. Famous women scholars included Ghosha and Gargi.

The Upanishads, another part of Hindu scriptures from around 500 BC, were "wisdom teachings" that looked at the deeper meaning of rituals. They encouraged students and teachers to explore ideas together, using questions and reasoning.

The Gurukula system was a traditional Hindu school where students lived with their teacher (Guru) in their home or a monastery. Teachers and students were seen as equals. Education was free, but rich students might give a "Gurudakshina" (a voluntary gift) to their Guru after finishing their studies, as a sign of respect. In Gurukulas, students learned about religion, scriptures, philosophy, literature, warfare, politics, medicine, and history.

Two long poems, the Mahabharata and Ramayana, were also part of ancient Indian education. The Mahabharata (possibly from the 8th century BC) talks about life goals and how people relate to society. The Ramayana (compiled between 400 BC and 200 AD) explores themes of human life and duty.

Buddhist Education

In the Buddhist education system, students studied the Pitakas:

- Vinaya Pitaka: Rules for Buddhist monks to live disciplined lives and interact respectfully with people and nature.

- Sutta Pitaka: Buddha's teachings, mostly recorded as sermons.

- Abhidhamma Pitaka: A summary and analysis of Buddha's teachings.

An early learning center in India was Taxila (also called Takshashila), from the 5th century BC. It taught the Vedas and many other skills. It was an important center for both Vedic/Hindu and Buddhist learning until the 5th century AD.

Another key learning center from the 5th century CE was Nalanda. This famous Buddhist monastery in Magadha attracted scholars and students from Tibet, China, Korea, and Central Asia. Vikramashila was another large Buddhist monastery, set up in the 8th to 9th centuries.

Education in China

According to old stories, the rulers Yao and Shun (around 24th–23rd century BC) started the first schools. The first education system was created in the Xia dynasty (2076–1600 BC). During this time, the government built schools to teach rich people about rituals, literature, and archery.

During the Shang dynasty (1600 BC to 1046 BC), ordinary people (like farmers) received basic education, while children of rich families went to government schools. Government schools were in cities and taught rituals, literature, politics, music, arts, and archery. Private schools were in rural areas and taught farming and crafts.

During the Zhou dynasty (1045–256 BC), there were five national schools in the capital city. These schools mainly taught the Six Arts: ceremonies, music, archery, chariot driving, writing, and mathematics. Boys learned ritual arts at age twelve, and later archery and chariot driving. Girls learned rituals, good manners, and how to make silk and weave.

It was during the Zhou dynasty that Chinese philosophy began. Confucius (551–479 BC) was a Chinese philosopher who greatly influenced later generations and the Chinese education system for over 2000 years.

Later, during the Qin dynasty (246–207 BC), officials were needed to control the empire. To become an official, people needed to be able to read and write and know a lot about philosophy. The education system aimed to create morally good and well-rounded people.

During the Han dynasty (206–221 AD), boys started learning basic reading, writing, and math at age seven. In 124 BC, Emperor Wu of Han started the Imperial Academy, which taught the Five Classics of Confucius. By the end of the Han dynasty (220 AD), the academy had over 30,000 students, boys aged fourteen to seventeen. However, education during this time was mostly for the wealthy.

The nine-rank system was used during the Three Kingdoms (220–280 AD) and Northern and Southern dynasties (420–589 AD) to choose government officials. In theory, local officials picked talented people and put them into nine grades based on their skills. But in practice, only the rich and powerful were chosen. This system was later replaced by the imperial examination system in the Sui dynasty (581–618 AD).

Education in Greece and Rome

In the city-states of ancient Greece, most education was private, except in Sparta. For example, in Athens (5th and 4th century BC), the government had little to do with schooling, except for two years of military training. Anyone could open a school and decide what to teach. Parents chose schools based on what they wanted their children to learn and what they could afford. Most parents, even poor ones, sent their sons to school for a few years, usually from age seven to fourteen. They learned gymnastics (sports and wrestling), music (poetry, drama, history), and reading and writing. Girls rarely received formal education. At writing school, young students learned the alphabet by singing and then by copying letters. After some schooling, sons of poor or middle-class families often learned a trade by working with their father or another tradesman. By around 350 BC, it was common for children in Athens to also study arts like drawing and painting. The richest students continued their education with sophists, learning subjects like public speaking, mathematics, and politics. Famous schools of higher education in Athens included the Lyceum (started by Aristotle) and the Platonic Academy (started by Plato).

The education system in the Greek city-state of Sparta was very different. It was designed to create strong warriors who were completely obedient and brave. At age seven, boys were taken from their homes to live in school dorms or military camps. They were taught sports, endurance, and fighting, with very strict rules. Most people in Sparta could not read or write.

The first schools in Ancient Rome appeared around the mid-4th century BC. These schools focused on teaching young Roman children basic social skills and education. It's estimated that only about 1-2% of people could read and write in the 3rd century BC. There isn't much information about Roman education until the 2nd century BC, when many private schools opened in Rome. During the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire, the Roman education system became more organized. Formal schools were set up for students who paid fees (there was little free public education). Both boys and girls usually went to school, though not always together. The Roman system was similar to modern schools, with different levels. The educator Quintilian believed it was important to start education as early as possible, saying that memory is "specially retentive at that age." A Roman student would move through schools like elementary, middle, high school, and then college today. Progress depended more on ability than age, and also on whether a student could afford higher education. Only the Roman elite usually received a full formal education. Tradesmen or farmers learned most of their job skills on the job. Higher education in Rome was often more about status than practical use.

Literacy rates in the Greek and Roman world were generally low, often not much more than 10% in the Roman Empire.

Formal Education in the Middle Ages (500–1500 AD)

Education in Europe

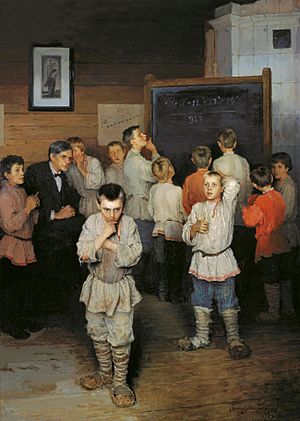

The word "school" in the Middle Ages meant different types of learning places, including town, church, and monastery schools. In the later Middle Ages, students in town schools were usually between seven and fourteen years old. Boys learned basic reading and writing (alphabet, simple prayers) and more advanced Latin. Sometimes, these schools also taught basic math or letter writing for business. Often, different levels of learning happened in the same classroom.

In the Early Middle Ages, Christian monasteries were the main centers of education and reading. They kept Latin learning alive and continued the art of writing. Before formal universities, many medieval universities started as Christian monastic schools where monks taught classes. Later, they became cathedral schools.

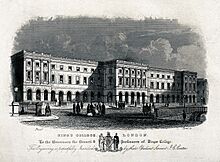

The first medieval places generally called universities were started in Italy, France, and England in the late 11th and 12th centuries. They taught arts, law, medicine, and theology. These universities grew from older Christian cathedral and monastic schools.

Students in the 12th century were very proud of the teacher they studied with, rather than the place. For example, students of Robert of Melun were called Meludinenses, even though they studied in Paris. People in the 12th century were very interested in learning the special and difficult skills that masters could teach.

Ireland became known as the "island of saints and scholars." Monasteries were built all over Ireland and became important learning centers.

Northumbria was famous for religious learning and arts. Monks from the Celtic Church helped spread Christianity there, leading to many monasteries and a unique art style called Insular art. After 664 AD, Roman church practices became official, but the Anglo-Celtic art style continued, seen in famous works like the Lindisfarne Gospels. The Venerable Bede (673–735) wrote his important history book in a Northumbrian monastery.

During the time of Charlemagne, King of the Franks (768 to 814 AD), who united most of Western Europe, there was a burst of literature, art, and architecture called the Carolingian Renaissance. Charlemagne learned about other cultures through his conquests and greatly increased the number of monastic schools and places for copying books (scriptoria) in his empire. Most of the old Latin works that still exist today were copied and saved by scholars during his reign.

Charlemagne was very interested in learning. He made sure his children and grandchildren were well-educated and even studied himself. He invited the English monk Alcuin to his court, who brought with him the excellent classical Latin education from Northumbrian monasteries. This return of Latin skills was important for the development of medieval Latin. Charlemagne's government used a common writing style called Carolingian minuscule, which helped communication across Europe.

Charlemagne also tried to create free basic education for young people through parish priests in 797. He ordered priests to "establish schools in every town and village" and teach children without charging fees, only accepting voluntary gifts.

Cathedral schools and monasteries remained important throughout the Middle Ages. In 1179, the Church ordered priests to offer free education to their communities. The "Scholastic Movement" in the 12th and 13th centuries spread through monasteries. However, by the 11th century, universities started to appear in major European cities, growing out of monastic schools. This made reading and writing available to more people, and there were big improvements in art, sculpture, music, and architecture.

In 1120, Dunfermline Abbey in Scotland established the first high school in the UK, Dunfermline High School. This shows how monasteries helped develop education.

Sculptures, paintings, and stained glass windows were important ways to teach Bible stories and the lives of saints to people who couldn't read.

Education in the Islamic World

The University of al-Qarawiyyin in Fes, Morocco, is the oldest existing university in the world that gives out degrees, according to UNESCO and Guinness World Records.

The House of Wisdom in Baghdad was a library, translation center, and school from the 9th to 13th centuries. Scholars translated works on astrology, mathematics, agriculture, medicine, and philosophy. They gathered knowledge from Persian, Indian, and Greek texts and added their own discoveries. The House was a leading center for studying humanities and sciences like mathematics, astronomy, and medicine. Baghdad was known as the world's richest city and a center for new ideas, with over a million people.

The Islamic mosque school (Madrasah) taught the Quran in Arabic and was different from medieval European universities.

In the 9th century, Bimaristan medical schools were created in the medieval Islamic world. These schools gave medical diplomas to students who were qualified to be doctors. Al-Azhar University, founded in Cairo, Egypt in 975, was a "university" that offered many advanced degrees. It had a Madrasah and taught Islamic law, Arabic grammar, Islamic astronomy, and early Islamic philosophy.

Under the Ottoman Empire, the towns of Bursa and Edirne became major learning centers.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, Timbuktu in West Africa became an important Islamic learning center, attracting students from as far away as the Middle East. It was home to the famous Sankore University and other madrasas. These schools mainly taught the Qur'an, but also logic, astronomy, and history. Many old manuscripts, some from before Islam and the 12th century, were collected there. More than 18,000 manuscripts are kept at the Ahmed Baba center.

Education in China (Middle Ages)

Even though there are over 40,000 Chinese characters, many are rarely used. To be fully able to read and write in Chinese, you only need to know about three to four thousand characters.

In China, children learned written characters and basic Confucian ideas by memorizing three oral texts:

- The Thousand Character Classic: A 6th-century poem with 1,000 unique characters, used for over a thousand years to teach children. It was sung like the alphabet song.

- The Hundred Family Surnames: A rhyming poem from the 11th century listing over 400 common Chinese surnames.

- The Three Character Classic: From around the 13th century, this text taught young children Confucianism. It was written in three-character verses for easy memorization. It taught common characters, grammar, Chinese history, and basic Confucian morals.

After learning characters, students who wanted to rise in society had to study the Chinese classic texts.

The early Chinese government needed educated officials to run the empire. In 605 AD, during the Sui dynasty, an examination system was officially started to choose local talented people. This imperial examination system for selecting officials led to schools that taught the Chinese classic texts. It was used for 1,300 years until 1911, when Western education methods replaced it. The main part of the exams from the mid-12th century was the Four Books, which were an introduction to Confucianism.

In theory, any adult male in China, no matter how rich or poor, could become a high-ranking government official by passing the imperial examination. However, studying for the exam took a lot of time and money, so most candidates came from wealthy land-owning families. Still, there are many stories in Chinese history of people from low social status becoming important officials through success in these exams.

Around 1040–1050 AD, local schools had been neglected. The chancellor of China, Fan Zhongyan, ordered that government and private money be used to fix and rebuild all neglected schools. He also tried to restore county-level schools. Fan's idea of government funding for education started a trend of public schools becoming more important than private ones.

Education in India (Middle Ages)

Even during the Middle Ages, education in India was taught by speaking. It was free, and people thought it was a holy and honorable thing to do. Kings didn't fund education, but Hindu people donated money to keep Hindu education alive. Hindu learning centers, which were universities, were built where scholars lived. These places also became pilgrimage sites, so more pilgrims donated money to them.

Islamic Education in India

After Muslims started ruling India, Islamic education spread. The main goals of Islamic education included gaining knowledge, spreading Islam and its morals, and preserving Muslim culture. Education was mainly given through Maqtabs, Madrassahas, and Mosques. This education was usually funded by rich people or landlords. Lessons were taught orally, and children memorized verses from the Quran.

In the 18th century, local education was common in India, with a school in almost every temple, mosque, or village. Subjects included reading, writing, math, theology, law, astronomy, and medicine. Students from all parts of society attended these schools.

Education in Japan (Middle Ages)

The history of education in Japan goes back to at least the 6th century, when Chinese learning came to the Yamato court. Other cultures often brought new ideas that helped Japan's own culture grow.

Chinese teachings and ideas flowed into Japan from the 6th to 9th centuries. Along with Buddhism, the Chinese system of writing and its literature, and Confucianism were introduced.

By the 9th century, Heian-kyō (today's Kyoto), the capital, had five higher learning institutions. During the rest of the Heian period, other schools were started by noble families and the imperial court. During the medieval period (1185–1600), Zen Buddhist monasteries were especially important learning centers. The Ashikaga School became a major higher learning center in the 15th century.

Education in Central and South American Civilizations

Aztec Education

The Aztecs were groups of people in central Mexico who spoke the Nahuatl language and became very powerful in Mesoamerica from the 14th to 16th centuries.

Until age fourteen, children were educated by their parents, but local authorities watched over them. Part of this education involved learning sayings called huēhuetlàtolli ("sayings of the old"), which showed Aztec ideals. These sayings seemed to have developed over centuries, even before the Aztecs.

At 15, all boys and girls went to school. The Aztecs were among the first people in the world to have required education for almost all children, no matter their gender or social status. There were two types of schools: the telpochcalli, for practical and military training, and the calmecac, for advanced learning in writing, astronomy, politics, and religion.

Aztec teachers aimed to create strong and disciplined people.

Girls were taught skills for home and raising children. They did not learn to read or write. All women were taught about religion, and paintings show women leading religious ceremonies, but there are no records of female priests.

Inca Education

Inca education during the Inca Empire (15th and 16th centuries) had two main parts: education for the upper classes and education for everyone else. Royal families and a few special people from the empire's provinces were formally taught by the Amautas (wise men). Most people learned knowledge and skills from their parents and older family members.

The Amautas were a special group of wise men, like storytellers. They were famous philosophers, poets, and priests who kept Inca history, culture, customs, and traditions alive by telling them throughout the kingdom. They were seen as the most educated and respected men in the Empire. The Amautas were mainly in charge of educating royal family members and young people from conquered cultures who were chosen to govern regions. So, education in the Inca lands was unequal, with most people not getting the formal education that royalty received.

The official language of the empire was Quechua, though many local languages were spoken. The Amautas made sure that everyone learned Quechua as the language of the Empire, similar to how the Romans promoted Latin. This was done more for political reasons than for education.

Education After the 15th Century

Education in China

In the 1950s, the Chinese Communist Party quickly expanded primary education across China. They also changed the primary school lessons to focus on practical skills, hoping to make future workers more productive. Chinese news sources at the time said that ending illiteracy was necessary "to open the way for development of productivity and technical and cultural revolution." Chinese officials saw a strong link between education and "productive labor." Like in the Soviet Union, the Chinese government expanded education to improve their national economy.

Education in Europe

Europe Overview

Modern education systems in Europe came from schools of the High Middle Ages. Most schools then were based on religious ideas, mainly to train clergy. Many early universities, like the University of Paris (founded in 1160), had a Christian foundation. There were also some non-religious universities, like the University of Bologna (founded in 1088). Free education for the poor was officially ordered by the Church in 1179. It said that every cathedral must have a master to teach boys who were too poor to pay. Parishes and monasteries also set up free schools for basic reading and writing. Priests and brothers usually taught locally, and towns often helped pay their salaries. Private schools also reappeared in medieval Europe, but they were also religious. The lessons were usually based on the trivium and quadrivium (the seven Liberal arts) and were taught in Latin, which was the common language for educated people in Western Europe.

In northern Europe, this religious education was largely replaced by basic schooling after the Protestant Reformation. In Scotland, for example, the national Church of Scotland planned for a school teacher in every church parish and free education for the poor in 1561. This was made law by the Parliament of Scotland in 1633, which introduced a tax to pay for it. Although few countries had such widespread education systems then, education became much more common between the 16th and 18th centuries.

Mass compulsory schooling started in Prussia around 1800 to "produce more soldiers and more obedient citizens."

Central and Eastern Europe

In Central Europe, the 17th-century scientist and educator John Amos Comenius promoted a new system of universal education that was widely used in Europe. Its growth led to governments becoming more interested in education. In the 1760s, Ivan Betskoy was appointed by Russian Tsarina Catherine II as an education advisor. He suggested educating young Russians of both genders in state boarding schools to create "a new race of men." Betskoy argued for general education over specialized training. Some of his ideas were put into practice at the Smolny Institute he set up for noble girls in Saint Petersburg.

Poland established a Commission of National Education in 1773. This commission was the first government Ministry of Education in a European country.

Universities

By the 18th century, universities started publishing academic journals. By the 19th century, German and French university models were well-known. The French created the Ecole Polytechnique in 1794, which became a military academy under Napoleon. The German university model, started by Wilhelm von Humboldt, focused on the importance of seminars and laboratories. In the 19th and 20th centuries, universities focused on science and served mostly upper-class students. Science, mathematics, theology, philosophy, and ancient history were common subjects.

Growing academic interest in education led to studying teaching methods. In the 1770s, the first professor of pedagogy (the study of teaching) was appointed at the University of Halle in Germany. Other important contributions to education studies in Europe came from Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi in Switzerland and Joseph Lancaster in Britain.

In 1884, a major education conference was held in London, bringing together experts from all over Europe.

19th Century Europe

In the late 19th century, most of Western, Central, and parts of Eastern Europe began to offer basic education in reading, writing, and math. This was partly because politicians believed education was needed for people to behave well politically. As more people learned to read and write, they realized that most secondary education was only for those who could afford it. After creating primary education, major nations had to focus more on secondary education by the time of World War I.

20th Century Europe

In the 20th century, new ideas in education included Maria Montessori's Montessori schools in Italy, and Rudolf Steiner's Waldorf education in Germany.

Education in France

Before 1789, schools in France were becoming more organized, mainly to train people for the church and government. France had many small local schools where working-class children learned to read. Boys and girls from noble and wealthy families received different educations: boys went to upper schools or universities, while girls might go to a convent for finishing. The Age of Enlightenment questioned these old ideas, but no real alternative for girls' education appeared.

The modern era of French education began in the 1790s. The Revolution abolished traditional universities. Napoleon wanted to replace them with new institutions like the Polytechnique, which focused on technology. Elementary schools received little attention until 1830, when France copied the Prussian education system.

In 1833, France passed the Guizot Law, the first major law for primary education. This law required all local governments to set up primary schools for boys. It also created a common curriculum that focused on moral and religious education, reading, and math. The expansion of education under this law was largely to shape the moral character of future French citizens and promote social order.

Jules Ferry, a politician in the 1880s, created the modern public school (l'école républicaine) by making it mandatory for all children under 15—boys and girls—to attend. Schools were free and non-religious (laïque). The goal was to reduce the influence of the Catholic Church and monarchy on young people. Catholic schools were still allowed, but in the early 20th century, the religious groups running them were closed down.

French Empire Education

French colonial officials tried to make schools, lessons, and teaching methods as standard as possible, influenced by the idea of equality. They didn't set up colonial schools to help local people advance, but rather to bring the French system to the colonies. Having a moderately trained local bureaucracy was useful for colonial officials. The French-educated local elite didn't see much value in educating rural people. After 1946, the policy was to bring the best students to Paris for advanced training. This led to the next generation of leaders being exposed to anti-colonial ideas in Paris.

Tunisia was an exception. The colony was managed by Paul Cambon, who built an education system for both colonists and local people that was very similar to mainland France. He focused on female and vocational education. By the time Tunisia became independent, its education quality was almost as good as in France.

African nationalists rejected this public education system, seeing it as a way to slow down African development and keep colonial power. One of the first demands of the nationalist movement after World War II was to have full French-style education in French West Africa, promising equality with Europeans.

In Algeria, the debate was very divided. The French set up schools based on science and French culture, which the French settlers (Pied-Noir) liked. But the Muslim Arabs rejected these goals, valuing mental skills and their religious traditions. The Arabs refused to become patriotic Frenchmen, and a unified education system was impossible until the Pied-Noir and their Arab allies left after 1962.

In South Vietnam from 1955 to 1975, there were two competing colonial powers in education: the French and the Americans. They disagreed sharply on goals. French educators wanted to preserve French culture among Vietnamese elites. The Americans focused on the general population, aiming to make South Vietnam strong enough to stop communism. The Americans had much more money, and their aid agency funded expert teams. The French strongly disliked the American involvement in their cultural area.

Education in England

In 1818, John Pounds started a school and taught poor children reading, writing, and math for free. In 1820, Samuel Wilderspin opened the first infant school. Starting in 1833, Parliament voted money to help pay school fees for poor children in England and Wales. In 1837, Lord Chancellor Henry Brougham helped prepare for public education. Most schooling was done in church schools, and religious disagreements between the Church of England and other Christian groups were a major issue in education before 1900.

Education in Denmark

The Danish education system began with cathedral and monastery schools set up by the Church. Seven of these schools from the 12th and 13th centuries still exist today. After the Protestant Reformation in 1536, the King took over the schools. Their main goal was to prepare students for religious studies by teaching them Latin and Greek. Basic education for ordinary people was very simple then. But in 1721, 240 "cavalry schools" were set up. Also, the religious movement of Pietism in the 18th century required some reading ability, which encouraged public education. Throughout the 19th century, the Danish system was greatly influenced by N. F. S. Grundtvig, who promoted inspiring teaching methods and the creation of folk high schools. In 1871, secondary education was divided into two paths: languages and mathematics-science. This division was the main structure of the Gymnasium (academic high school) until 2005.

In 1894, the Folkeskole ("public school," the government-funded primary system) was formally established. Steps were taken to improve education to meet the needs of an industrial society.

In 1903, the 3-year Gymnasium course was directly linked to municipal schools by creating the mellemskole ('middle school', grades 6–9), which was later replaced by the realskole. Before this, students wanting to go to Gymnasium had to get private lessons because municipal schools were not enough.

In 1975, the realskole was removed, and the Folkeskole (primary education) became a system where all students go to the same schools, regardless of their academic abilities.

Education in Norway

Soon after Norway became an archdiocese in 1152, cathedral schools were built to educate priests in Trondheim, Oslo, Bergen, and Hamar. After the Reformation in 1537, these schools became Latin schools, and it was made mandatory for all market towns to have one. In 1736, learning to read became compulsory for all children, though it took some years to be effective. In 1827, Norway introduced the folkeskole, a primary school that became mandatory for 7 years in 1889 and 9 years in 1969. In the 1970s and 1980s, the folkeskole was replaced by the grunnskole.

In 1997, Norway created a new curriculum for elementary and middle schools. This plan focused on national identity, being child-centered, and community-oriented, along with new teaching methods.

Education in Sweden

In 1842, the Swedish parliament introduced a four-year primary school for children, called "folkskola". In 1882, two more grades (5 and 6) were added. Some "folkskola" also had grades 7 and 8, called "fortsättningsskola". Schooling in Sweden became mandatory for 7 years in the 1930s, for 8 years in the 1950s, and for 9 years in 1962.

The number of students grew slowly from 1900–1947, then rapidly in the 1950s, and declined after 1962. Birth rates were a big reason. Also, the high school (gymnasium) became open to more people based on talent, not just social class. Central economic planning, the focus on education for economic growth, and the increase in office jobs also played a role.

Education in Japan (After 15th Century)

Japan isolated itself from the rest of the world in 1600 under the Tokugawa shogunate (1600–1867). In 1600, very few common people could read and write. By the end of this period, learning was widespread. Tokugawa education left a valuable legacy: more people could read, there was a belief that hard work led to success, and there was a focus on discipline. Traditional Samurai education for the elite emphasized morals and martial arts. They memorized Confucian classics and often read and recited them. Math and calligraphy were also studied. Education for commoners was practical, teaching basic reading, writing, and how to use an abacus. Much of this education happened in "temple schools" (terakoya), which came from earlier Buddhist schools. By 1867, these schools were no longer religious and were not mainly in temples. By the end of the Tokugawa period, there were over 11,000 such schools with 750,000 students. Teaching involved reading textbooks, memorizing, using the abacus, and copying Chinese and Japanese characters. By the 1860s, 40–50% of Japanese boys and 15% of girls had some schooling outside the home. These rates were similar to major European countries at the time (except Germany, which had mandatory schooling). This foundation helped Japan quickly change from a feudal society to a modern nation under later Meiji leaders, who paid close attention to Western science, technology, and education.

Meiji Reforms

After 1868, reformers quickly modernized Japan with a public education system like Western Europe's. Missions like the Iwakura mission were sent abroad to study Western education systems. They returned with ideas of local school boards and teacher independence. Elementary school enrollment grew from about 40-50% in the 1870s to over 90% by 1900, despite public protests, especially against school fees.

A modern idea of childhood appeared in Japan after 1850 as it connected with the West. Meiji leaders decided the nation should be the main force in organizing individuals—and children—to serve the state. Western-style schools became the tool for this goal. By the 1890s, schools created new ideas about childhood. After 1890, Japan had many reformers, child experts, and educated mothers who adopted this new way of thinking. They taught the upper middle class a model of childhood where children had their own space, read children's books, played with educational toys, and spent a lot of time on school homework. These ideas quickly spread to all social classes.

After 1870, school textbooks based on Confucianism were replaced by Westernized texts. However, by the 1890s, there was a shift back to a more strict approach. Traditional Confucian and Shinto ideas were emphasized again, especially about hierarchy, serving the new state, seeking knowledge, and morality. These ideals, found in the 1890 Imperial Rescript on Education, along with strong government control over education, guided Japanese education until 1945, when they were largely rejected.

Education in India (After 15th Century)

Education was common for elite young men in the 18th century, with schools in most regions of the country. Subjects included reading, writing, math, theology, law, astronomy, and medicine.

The current education system in India, with its Western style and content, was introduced by the British during the British Raj. This followed recommendations by Lord Macaulay, who wanted English taught in schools and a class of English-speaking Indian interpreters. Traditional Indian education structures were not recognized by the British government and have declined since then.

Public education spending in the late 19th and early 20th centuries varied greatly across regions. Western and southern provinces spent three to four times more than eastern provinces. Much of this difference was due to historical differences in land taxes, which were the main source of income.

Lord Curzon, the Viceroy from 1899–1905, made mass education a high priority after finding that no more than 20% of India's children attended school. His reforms focused on teaching reading and writing and changing university systems. They emphasized flexible lessons, modern textbooks, and new examination systems. Curzon's plans for technical education laid the groundwork for later governments.

Education in Australia, Canada, New Zealand

In Canada, education became a debated topic after Confederation in 1867, especially concerning French schools outside Quebec.

Education in New Zealand began with provisions from provincial governments, Christian missionary churches, and private education. The first education law was passed in 1877, aiming to set a standard for primary education. It made it mandatory for children to attend school from age 6 to 16.

In Australia, mandatory education was enacted in the 1870s, but it was hard to enforce. People found it difficult to afford school fees, and teachers felt they were not paid enough.

Education in Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union

In Imperial Russia, according to the 1897 census, 28% of the population could read and write. There was a strong network of universities for the upper class, but less provision for everyone else.

Vladimir Lenin, in 1919, declared that the main goal of the Soviet government was to end illiteracy. A system of universal mandatory education was set up. Millions of adults who couldn't read or write were enrolled in special literacy schools. Youth groups helped teach. In 1926, 56.6% of the population could read and write. By 1937, this rate was 86% for men and 65% for women, making the total literacy rate 75%.

The fastest growth of primary schooling in the Soviet Union happened during the First Five-Year Plan. This rapid expansion was largely due to Stalin's interest in making sure everyone had the skills to help the state's industrialization and goal of international power. U.S. officials visiting the USSR were surprised by "the extent to which the Nation is committed to education as a means of national advancement."

An important part of the early literacy campaign was the policy of "indigenization" (korenizatsiya). This policy, from the mid-1920s to late 1930s, promoted the use of non-Russian languages in government, media, and education. It aimed to counter past Russification and provide native-language education as the quickest way to improve education levels for future generations. A large network of "national schools" was established by the 1930s and continued to grow. Language policy changed over time, with Russian becoming a required subject in non-Russian schools in 1938, and later becoming the main language of instruction in many schools from the late 1950s.

Education in the United States

Education in Turkey

In the 1920s and 1930s, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881–1938) made big changes to education in Turkey to modernize it. He first separated government and religious affairs. Education was key to this effort. In 1923, there were three main types of schools:

- Traditional medreses based on Arabic, the Qur'an, and memorization.

- Reformist schools from the Tanzimat era.

- Colleges and minority schools in foreign languages that used modern teaching methods.

Atatürk modernized the old medrese education. He changed classical Islamic education for a strong rebuilding of schools. He believed educational reform was more important than the Turkish War of Independence for freeing the nation from old ideas. He said:

Today, our most important and most productive task is the national education [unification and modernization] affairs. We have to be successful in national education affairs and we shall be. The liberation of a nation is only achieved through this way."

In 1924, Atatürk invited American education reformer John Dewey to advise him on how to change Turkish education. Education was unified in 1924, making it inclusive and organized like a civil community. All schools had to follow the curriculum of the "Ministry of National Education," a government agency. At the same time, the republic abolished the two religious ministries and put clergy under the religious affairs department, which was a foundation of secularism in Turkey. This unification ended the old "clerics or clergy of the Ottoman Empire," but it wasn't the end of religious schools in Turkey. They were moved to higher education until later governments brought them back to secondary education after Atatürk's death.

In the 1930s, at the suggestion of Albert Einstein, Atatürk hired over a thousand established academics, including world-famous professors escaping Nazi Germany. Most were in medicine, mathematics, and natural science. German exiled professors became directors in many of Istanbul's science institutes and medical clinics.

Education in Africa

Education in French-controlled West Africa in the late 1800s and early 1900s was different from the mandatory, uniform education in France. "Adapted education" was organized in 1903. It used the French curriculum but replaced French information with "comparable information drawn from the African context." For example, French morality lessons included references to African history and local stories. The French language was also taught as a key part of this adapted education.

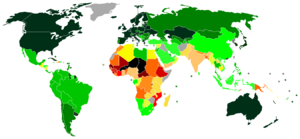

Africa has over 40 million children. In 2000, only 58% of children in sub-Saharan Africa were in primary schools, the lowest rate of any region. As of 2005, 40% of school-aged children in Africa did not attend primary school.

Recent World-Wide Trends

Today, most countries have some form of compulsory education (where schooling is required). Because of population growth and more mandatory schooling, UNESCO estimates that more people will receive formal education in the next 30 years than in all of human history combined.

Illiteracy (not being able to read or write) and the percentage of people without any schooling have decreased over the past few decades. For example, the percentage of people without any schooling dropped from 36% in 1960 to 25% in 2000.

In developing countries, illiteracy and percentages without schooling in 2000 were about half of what they were in 1970. In developed countries, illiteracy rates are very low, often less than 1%. Illiteracy decreased greatly in less economically developed countries (LEDCs) and almost disappeared in more economically developed countries (MEDCs). The percentages of people without any schooling showed similar patterns.

Since the mid-20th century, societies worldwide have seen faster changes in economy and technology. This has greatly affected workplaces and what schools need to teach students for jobs. Starting in the 1980s, governments, educators, and major employers identified key skills needed for the changing, more digital workplace and society. 21st century skills are higher-level skills, abilities, and ways of learning that experts say are needed for success in today's world. Many of these skills involve deeper learning, such as analytical thinking, solving complex problems, and teamwork, rather than just memorizing facts.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la educación para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la educación para niños

- Factory model school

- History of childhood

- Social history#History of education

- History of childhood care and education