History of Worcestershire facts for kids

Worcestershire has been home to people for over half a million years! Even with two ice ages, people have lived here continuously for about 10,000 years. During the Iron Age, the area had many hill forts. People also started making pottery and mining salt. The area wasn't super important during the Roman times, except for its salt mines.

In the Anglo-Saxon era, Worcestershire was a big center for the Church and learning. The county got its name and became a political area in 918 AD.

From the Middle Ages, the city of Worcester became very important. Its merchants, Church leaders, and wealthy families held most of the power. Sometimes, they didn't always agree!

Worcestershire played a key role in the English Civil War. It was a front-line area for the Royalists and already known for metalworking and small weapons. King Charles II was defeated here at the Battle of Worcester in 1651. Local Catholic nobles helped him escape. Many important religious leaders from northern Worcestershire later left the Anglican church during the Great Ejection.

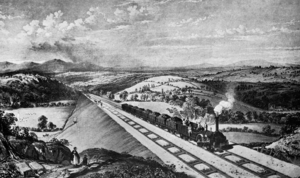

The northern part of Worcestershire, including Dudley and Netherton, was a major hub during the British Industrial Revolution. Dudley was famous for iron and coal. Kidderminster made carpets, Stourbridge made glass, and Bromsgrove made nails. Redditch was known for needles and fish hooks. Canals and railways helped send these goods all over.

Today, Worcestershire is still important for farming, especially in the Vale of Evesham. Some local government changes mean that Dudley and parts of Birmingham are no longer in Worcestershire.

Contents

Ancient Times: Prehistory in Worcestershire

Stone Age: Early Humans (Paleolithic)

We know humans lived in Worcestershire about 700,000 to 500,000 years ago. Flint axe heads have been found near Hallow, close to Worcester. It's hard to find much from this time because these early people were hunter-gatherers. They moved around a lot and didn't stay in one place. Most tools are found in sand and gravel pits.

The first people here likely followed the Bytham River system. This river used to flow east from Evesham. Ice ages pushed people away, but they returned around 300,000 years ago. Nearly 40 hand axes from this time have been found. Fifteen axes were found at Kemerton.

Middle Stone Age: Hunter-Gatherers (Mesolithic)

Between 10,000 and 3,500 BC, the climate got much better. Forests grew, and humans came back to the area. They still hunted and gathered food. We often find evidence of Mesolithic people through their flint tools. For example, 1,400 flint pieces were found near Kidderminster at Wribbenhall.

This site also had post holes, a fireplace, and a pit. It's thought to be the oldest settlement found in Worcestershire, dating back to about 6,800 BC. Pollen shows that people were already growing crops and clearing woodlands.

New Stone Age: Farmers Arrive (Neolithic)

We have more evidence from the Neolithic period. Finds were made before World War II in Bewdley, Lindridge, and Broadwas. A skull was even found in Worcester. Farming left many signs, like crop marks on gravel terraces. We can find settlements from post holes, such as at Huntsman's Quarry, Kemerton.

The most obvious Neolithic evidence comes from their special ritual sites. At Fladbury, a possible "cursus" was found. These were long enclosures that might have been lined up with the sky and stars. At Whittington Tump, a hill was made taller for ceremonies or burials.

Stone axes from this time show that people traded far and wide. Axes came from places like Brittany, Italy, Switzerland, Cornwall, North Wales, and the Lake District. Pottery also started to appear. Finds at Clifton, Severn Stoke, include special "Grooved ware" pottery and burnt stones used for cooking or perhaps even saunas!

Bronze Age: Metal Tools and Farming (Bronze Age)

Bronze Age tools and weapons are found in Worcestershire's valleys. Many are near river crossings on the Avon (like Harvington and Evesham) and the Severn (like Bewdley and Worcester). Flint axes and arrowheads from the Malvern area show early Bronze Age settlers. Burial sites called barrows also tell us a lot. About twenty barrows have been found, and two have been dug up at Holt and Wyre Piddle.

Worcestershire became mostly a farming area during the Bronze Age. Forests were cleared early in this period. Since not many cereal grains are found, it's thought the land was used more for cattle farming. Clearing forests also caused flooding in lower areas. People started living in more open settlements as the land became more settled.

Some of today's field systems might even date back to the late Bronze Age. For example, boundaries from the Bronze Age seem to match modern fields in Kerton and Wyre Piddle. The "Shire Ditch," a large earthwork from around 1000 BC, was a boundary that later settlements respected.

Bronze Age evidence also shows that people were casting bronze and making textiles at Kemerton.

Iron Age: Hill Forts and Industry (Iron Age)

From about 600 BC, iron became the main material for tools. It was harder than bronze and easy to shape. In Worcestershire, the most famous Iron Age sites are the hill forts. There are about ten or twelve still standing, including British Camp, Wychbury Hill, and Hanbury.

Many of these forts could be seen from each other. This suggests they were important centers for organization and power. They might have been meeting places, ways to control animals, places to store grain, homes, or tribal centers.

Farming in this period shows a mix of long-lasting settlements that weren't always perfectly stable. The middle of the Iron Age seems to have seen some farms and hill forts abandoned. However, there was also a lot of continuity into the Roman period.

The Wyche Cutting, a pass through the Malvern hills, was used in the Iron Age. It was part of a salt trade route from Droitwich to South Wales. A discovery in the 1800s of over two hundred metal money bars near the Wyche Cutting suggests that the Malvern area was home to the La Tène people around 250 BC.

Evidence of Iron Age salt production has been found at Droitwich. A pottery industry also started in the Malvern area, selling goods to nearby places. This pottery making continued into the Middle Ages.

Roman Times in Worcestershire

Before the Roman invasion, the Roman Empire had agreements with the Celtic Britons. Emperor Claudius successfully conquered Britain starting in 43 AD.

Excavations at Midsummer Hill fort, Bredon Hill, and Conderton Camp show signs of violent destruction around 48 AD. This might mean that British Camp was also left or destroyed around the same time.

Worcestershire was quickly behind the Roman front lines. This means there isn't much evidence of Roman soldiers here. There are about ten small road defenses, like one near Kempsey that belonged to the Roman Second Legion. There are also bridge remains over the Severn near Kempsey thought to be Roman.

Two forts were found at Dodderhill, next to the Droitwich salt workings. A fancy building with mosaics was also found here in 1847. There's evidence of Roman iron production in Worcester. However, there are no signs of big public buildings, just a small defended site, maybe to guard the river crossing.

Excavations at Kings Norton found signs of a small Roman-British settlement. This included kilns for making pottery. More recently, Roman pottery and a ditch were found near Icknield Street.

Worcestershire wasn't a major area for large Roman villas, except in its southeastern corner near the Cotswolds. This area had well-established Roman-style farming. Worcestershire also wasn't on the main Roman road network, though some smaller roads have been found.

Anglo-Saxon Worcestershire

The Roman system of government seemed to disappear quickly after their soldiers left. However, Worcestershire probably stayed Roman-British in culture, language, and religion. There's not much archaeological evidence from this time. Farming continued in Worcester, with some farmhouses and signs of animal grazing. St Helen's Church in Worcester might even have had British origins. Salt production in Droitwich also continued.

The Hwicce Kingdom

The Anglo-Saxons took over this area fairly late. Gloucester and Bath were captured around 577 by the West Saxons. In 613, the Welsh were pushed beyond the River Dee. In these early years, very small kingdoms might have been set up, like the Weorgoran, from whom Worcester is believed to get its name.

The area we call Worcestershire was part of the early English kingdom of the Hwicce. This kingdom quickly became part of Mercia. The exact borders of the Hwicce kingdom are not certain. But it likely matched the old Diocese of Worcester. The name Hwicce still lives on in Worcestershire in names like Wichenford and Wychbury Hill.

Worcester's Church Power

The Diocese of Worcester was founded in 679–680. Early bishops were called Episcopus Hwicciorum. The diocese seemed to get a lot of support from the kings of Mercia in the 700s. With royal help, the bishopric slowly gained control over important churches called minsters. This process helped the Mercian kings by weakening local rivals and bringing in money from church lands.

Because of this, in the 800s, the bishopric of Worcester was the most powerful church in Mercia. From this strong position, the church used its wealth to buy special rights from the Mercian kings.

Later, King Alfred started to recruit priests and monks from Mercia, especially Worcester. He wanted their help to rebuild the church in Wessex in the 880s. It's believed these priests brought new ideas about the church's role in society. This led to a new way of thinking for the Anglo-Saxon church.

Between 900 and 1060, the church lost some of its lands. This was due to leases and lost records. Leases were often for three lifetimes but often became permanent. By the time of the Domesday Book, about 45% of the diocese's church lands were held by tenants.

Worcester was a center for monastic learning and church power. Oswald of Worcester was an important reformer. He was appointed Bishop in 961, also serving as Bishop of York. The last Anglo-Saxon Bishop of Worcester, Wulfstan, or St Wulstan, was also a key reformer. He stayed in his role until he died in 1095.

Alfred and Edward's Influence

Worcestershire became part of the unified Kingdom of England in 927. This is also when it was first set up as a county. It was briefly a separate earldom in the 900s. Then it became part of the Earldom of Mercia in the 1000s. Before the Norman conquest in 1066, the Church, including Priory Cathedral, Evesham Abbey, and other religious houses, controlled more and more of the county.

During King Alfred's reign, the earls of Mercia fortified Worcester. This was "for the protection of all the people" at the request of Bishop Werfrith. The townspeople were supposed to pay for keeping up the defenses. A unique document from this time describes Worcester's market and court. It also shows how the church and market areas were separate.

Worcester's fortifications likely set the line for the wall that stood until the 1600s. It was called a wall by people at the time, so it might have been made of stone.

Worcester became a center of tax resistance against the Danish Harthacanute. Two of his tax collectors were killed in May 1041. A military force was sent to deal with this. The townspeople tried to defend themselves by moving to Bevere island, two miles up the river. They were then surrounded. After Harthacnut's men sacked and burned the city, an agreement was reached.

The last Anglo-Saxon sheriff of the county was Cyneweard of Laughern.

Medieval Worcestershire

Economy and Life in the Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, much of Worcestershire's economy relied on the wool trade. Many of its thick forests, like Feckenham Forest and Wyre Forest, were royal hunting grounds. Droitwich Spa, with its large salt deposits, was a major salt production center since Roman times. One of the main Roman roads ran through the town.

Farming in the early Middle Ages grew by clearing more land, especially from forests. Extra food was limited, especially after feudal dues were paid. This left peasant farmers with just enough to live on. Poor harvests in 1315, 1316, and 1322 made food prices go up. This likely weakened people's health. The Black Death arrived in Worcestershire in 1348–9. Later outbreaks in 1361, 1369, and 1375 reduced the population by about a third. Some villages were completely abandoned.

The Priory Cathedral was a huge landowner and economic power in Worcester and the county. The Church and other monasteries owned more than half of the land in Worcestershire. This was a very high amount. The Priory also owned the manor of Bromsgrove, given by King Henry III. It was a center of learning and provided schooling. It was also linked to hospitals. The Church received part of local taxes. It had close political ties with leading wealthy families. So, Worcester's Cathedral was central to medieval life. As settled areas expanded into wooded parts, the church gained more wealth.

The Cathedral was one of several religious places in Worcester. Sometimes, rivalry between different religious groups caused problems. Wealthy families often supported specific groups.

The Droitwich salt industry was very important during the Domesday Survey. Bromsgrove alone sent 300 cartloads of wood each year to the salt-works. In the 1200s and 1300s, Bordesley monastery and the abbeys of Evesham and Pershore sold wool to markets in Florence and Flanders. Coal and iron were mined at Dudley from the 1200s.

Norman Conquest and Changes

The first Norman Sheriff of Worcestershire, Urse d'Abetot, oversaw the building of a new castle in Worcester. Nothing remains of it today. Worcester Castle was built by 1069. Its outer area was built on land that used to be a cemetery for the monks of Worcester cathedral. The castle's mound overlooked the river, just south of the cathedral.

Worcester's Bishop Wulfstan was the last Anglo-Saxon bishop in England.

Land Ownership After the Conquest

After the Norman conquest of England, the Domesday Book in 1086 noted that the Crown had no power in seven of Worcestershire's twelve areas called hundreds. The Bishop of Worcester and the Abbots of Pershore, Westminster, and Evesham held this power instead.

At this time, more than half of Worcestershire was owned by the church. The church of Worcester held the large Op.waldslow hundred. It had special rights, like keeping the sheriff out. The profits from all local courts went to the bishop. The two hundreds owned by Westminster and Pershore churches later combined to form Pershore hundred. The Evesham Abbey hundred became Blackenhurst hundred. The county court was held at Worcester.

William the Conqueror gave manors and parishes taken from the Anglo-Saxons to his allies. For example, Dudley and other manors like Selly Oak and Bromsgrove were given to Ansculf de Picquigny. Hala went to Roger de Montgomerie. The Doddingtree Hundred was given to Raoul II of Tosny and others. Despite the Norman Conquest, the Abbeys of Pershore and Evesham, and the Bishop of Worcester still held the rest of the county.

The first Norman Sheriff, Urse d'Abetot, built Worcester Castle. He also took a lot of church land. This land became part of the Crown's hundreds in Worcestershire. d'Abetot had arguments with Bishop Wulfstan over the sheriff's rights in church lands.

The Church's huge landholdings stopped a powerful group of nobles from growing in Worcestershire. Dudley Castle was the only home of a feudal baron. The lands of Urse d'Abitot and his brother passed to the Beauchamps in the 1100s. They owned Elmley and Hanley Castles.

Beauchamp Sheriffs

The job of Sheriff of Worcestershire was passed down in families, which was rare. The Beauchamp family held it. They were in charge of some laws, military duties, and collecting taxes. They had to pay fixed amounts to the King. They also often held Royal Forests, like Feckenham, for a payment. This led to a lot of corruption. In the 1200s, Walter de Beauchamp (justice) and his son William (III) de Beauchamp took taxes for themselves.

Walter de Beauchamp was removed in 1229 but got his job back within a year. No money was paid to the King for many years. William (III) de Beauchamp also didn't pay for Feckenham Forest for 12 years. He used his power to bother free tenants in the Doddingtree hundred until they paid a large yearly fine. An investigation in 1274-5 found he had "taken over" Doddingtree and Halfshire hundreds. He also had a long dispute with Bishop Walter de Cantilupe.

By the end of his life, William (III) de Beauchamp agreed to pay the King £10 a year to clear his debts. But these payments weren't enough. It's surprising that the King put up with the Beauchamp family's abuses.

King Stephen and the Anarchy

The 19-year fight between King Stephen and Empress Matilda for the English crown affected Worcestershire. Matilda's brother was the Earl of Gloucester, so Worcester was near one of her strong allies. When war started in 1138, Stephen attacked Dudley Castle, held by Ralf Pagenal, who supported Matilda. Stephen destroyed the countryside but couldn't take the castle. In 1139, Stephen visited Worcester and made offerings at the Cathedral. He also created the Earldom of Worcester for his ally, Waleran de Beaumont.

In 1140, Matilda's allies were in Gloucester. Rumors of an attack on Worcester by Matilda's forces made the citizens hide in the Cathedral. The attack came in November. Worcester's citizens fought off the attack at the castle, but houses were burned, people were taken for ransom, and animals were stolen. Waleran attacked Sudeley Castle and Tewkesbury in revenge.

Miles of Gloucester, the Sheriff, sided with the Empress. Stephen made William de Beauchamp Sheriff instead. William was put in charge of Worcester's castle in 1145.

In 1150, Waleran sided with Matilda and defended Worcester against Stephen. Worcester was burned and robbed again, this time by King Stephen. The war ended in 1153. Stephen agreed that Matilda's heir would become king after him.

Henry II's Rule

King Henry II quickly took back control in the Marches after he became king. He visited Worcester and was crowned there twice. In 1158, he held a Royal Council meeting in the city.

Henry II made many changes to the legal system. He set up circuits where judges would travel to courts. Worcestershire, Shropshire, Herefordshire, and Gloucestershire formed one of these circuits.

Henry II had a big argument with Thomas Becket. Worcester's Bishop Roger tried to support Becket and the Church's independence. He wrote to the King to help Becket after he was exiled. Henry told Roger to stay away from Becket. Roger ignored this and was also exiled. He stayed in exile even after the Pope tried to make peace. After Becket's murder, Roger was sent to Rome by the King to convince the Pope he wasn't involved.

Richard I and King John

Worcester got its first royal charter from King Richard I in 1189. This meant the city would pay £24 a year to the Crown directly. It also meant the county sheriff would no longer have general power over the city.

King John visited Worcester eleven times. He visited St Wulfstan's shrine in 1207. He seemed to like Wulfstan because he supported the power of kings. However, John didn't renew the city's charter. This allowed him to charge increasing and unfair taxes on Worcester.

John tried to claim the right to appoint English bishops. This led to a long argument with the Pope. Bishop Mauger of Worcester was appointed by the Pope to enforce his Interdict. Mauger was forced into exile, and his property was taken.

John spent Christmas 1214 in Worcester. This was during his arguments with the Barons over justice, before discussions leading to Magna Carta began. In 1216, the barons asked the French Dauphin to remove John from power. This brought conflict to Worcestershire. The county's leaders organized against John. William Marshall, who was loyal to John, took control of Worcester as governor. Ranulph, Earl of Chester attacked the city, took the castle, and robbed the Cathedral. Marshal escaped after being warned by his father.

The priory was fined for helping the rebels. They had to melt down treasures from St Wulfstan's tomb. Worcester city was fined £100 for its role. John could do this because the city didn't have a charter.

John was buried in the cathedral near Wulfstan's altar after he died.

Worcester's Jewish Community

Worcester had a small Jewish community by the late 1100s. It was one of the few places allowed to keep debt records in a special locked chest called an archa. Jewish life probably centered around what is now Copenhagen Street.

The diocese was very unfriendly to the Jewish community. Peter of Blois was asked by a Bishop of Worcester to write a strong anti-Jewish book around 1190.

William de Blois, as Bishop of Worcester, put very strict rules on Jews in 1219. Like elsewhere in England, Jews had to wear square white badges. In most places, this rule was ignored if fines were paid. Blois also tried to limit usury (lending money with interest). He wrote to Pope Gregory in 1229 asking for stricter rules. The Pope then demanded that Christians be stopped from working in Jewish homes and that badges be worn.

Henry III and the Barons' War

King Henry III gave the manor of Bromsgrove to Worcester Priory. This was to support a memorial for his father, King John.

In 1240, Henry III called a meeting of Jewish leaders in Worcester. He wanted to tax them. He "squeezed the largest tallage of the thirteenth century from his Jewish subjects."

Henry III had many arguments with his Barons. In the 1260s, this led to war. In 1263, Worcester's Jewish residents were attacked by a force led by Robert Earl Ferrers and Henry de Montfort. Most were killed. Ferrers used this chance to take the debt records from the archae.

The massacre in Worcester was part of a larger plan by the De Montforts to weaken Henry III. A massacre of London's Jewish community also happened during the war. Worcestershire was the site of the Battle of Evesham in 1265. Simon de Montfort was killed there, ending his allies' hopes of winning the war.

A few years later, in 1275, the Jews still living in Worcester were forced to move to Hereford. They were expelled from all towns under the queen mother's control.

Worcestershire in Parliament

By 1295, Worcestershire had sixteen members in Parliament. Two knights represented the county. Two citizens each represented Worcester city and the towns of Bromsgrove, Droitwich, Dudley, Evesham, Kidderminster, and Pershore. However, most towns stopped sending representatives. Droitwich did so until 1311 and again from 1554. Evesham got its right back in 1604. In 1606, Bewdley sent one member.

Under the Reform Act of 1832, the county sent four members. Droitwich lost one member. Dudley and Kidderminster got their right to send one member each back. In 1867, Evesham lost one member.

Early Modern Worcestershire

Industry and Farming Changes

In the 1500s, Worcestershire's clothing industry employed 8,000 people. It declined in the 1600s, but silk-making later took its place in Kidderminster and Blockley.

King Henry VIII limited cloth making to Bromsgrove, Kidderminster, Droitwich, Evesham, and Worcester. Rural cloth production grew because of poverty and the need for extra income. Trade in Worcester and cloth trade in Kidderminster were still controlled by guilds. Tanning was probably the largest industry across the county.

Glassmaking started in Stourbridge in the early 1600s, brought by Huguenot immigrants. Sir Robert Mansell got a national monopoly on glass production. This helped the local industry grow a lot. They started making window panes, bottles, and pots. In 1615, glass makers were told to use coal for fuel. This was because woodlands were being used up, and timber was needed for shipbuilding.

Northern Worcestershire was already known for metalwork. But it relied on small furnaces until just before the Civil War. Then, charcoal furnaces using water-powered bellows were introduced. Blacksmiths were not organized into guilds. This freedom might explain the industry's sudden growth in the 1600s.

Efforts to make iron with coal began in Dudley in the early 1600s. Dud Dudley wrote about this in his book Metallum martis.

Nailmaking became big in northern parts of the county, like Bromsgrove, Stourbridge, and Dudley. It helped people earn extra money in rural areas. It grew because the River Severn allowed access to national and international markets. Nailmasters, who bought nails from local makers, gained the most from this trade.

Scythe making was centered in the Clent Hills area because it needed water power. It was a skilled job, and scythe makers could be quite wealthy.

This period also saw many changes in farming. For example, tobacco was grown in Worcestershire in the Eckington and Evesham areas. It was banned in 1627 after pressure from colonial producers. Tobacco continued to be grown illegally for most of the century. The potato was introduced but not widely grown. In the northeast, grain production increased, as did cattle and sheep farming. Other new ideas included growing clover.

Hops might also have been introduced to Worcestershire around this time. Flax and hemp, important for the cloth trade, were grown. The county grew many fruit crops, especially apples and pears. Cider and perry production also thrived. Market gardening grew, especially in the Evesham area.

The Reformation's Impact

Worcester Priory ended with King Henry VIII's Dissolution of the Monasteries. The prior, William More, resigned in 1535. He was replaced by Henry Holbeach. More had a reputation for living well. There were also problems with the priory's management.

The Protestant Hugh Latimer was bishop from 1535. He preached for reform and removing religious images. He resigned in 1539 because Henry VIII moved back towards Catholicism. John Bell, a moderate reformer, was bishop from 1539 to 1543, during the priory's dissolution.

In the early 1500s, Worcester had about 40 monks. This number dropped just before 1540. There were 35 Benedictine monks plus Prior Holbeach when the priory was dissolved in 1540. Eleven were given pensions, and the rest became secular canons in the new Royal College. Holbeach became the first Dean.

Ending the monasteries greatly changed education for young people, mostly sons of wealthy families. They had been taught Latin and grammar in monastic schools. King Henry set up new grammar schools, often still linked to the Church. King's School, Worcester is one of these.

The old monastic library had many manuscripts. These are now in libraries like Cambridge, London, Oxford, and Worcester Cathedral. Parts of the priory from the 1100s and 1200s can still be seen. John Bell's successor, Nicholas Heath, was more conservative and Catholic. Records from the dissolution tell us about other religious houses in Worcestershire.

While Worcester Priory's lands went to the Chapter and Dean, others were sold off. Many places were ransacked. The lands were often sold to people connected to the court. Sir John Packington bought 30 manors in Worcestershire. This formed his estate, including Hampton Lovett and Chaddesley Corbett. Still, land ownership changes in Worcestershire were less than in other areas.

Even though Roman Catholicism was officially ended, some of Worcestershire's wealthy families remained Catholic. Several were involved in the Gunpowder Plot in 1604. Some Worcestershire houses have priest holes from the 1500s and 1600s (for example, Harvington Hall has seven).

The Reformation also changed rural customs and festivals. They became less religious. As Puritanism grew in the 1620s and 30s, village sports like Maypole and Morris dancing were attacked. Worcester even raised money to keep players out of the city. These activities did return after the restoration of the monarchy.

The Gunpowder Plot

Robert Wintour and other plotters planned to blow up the new Scottish Protestant King James I. They met at the Wintour's home at Huddington Court. Robert Catesby, the main plotter, was from Northampton. But most of the plotters were from Worcestershire's Catholic families.

Charles I and Growing Tensions

After 1629, King Charles I tried to rule without Parliament. This forced him to raise taxes, which affected Worcestershire. Selling royal lands, especially forests, led to attempts to enclose Malvern Chase. The more successful sale of Feckenham Forest in the 1630s caused riots. It also displaced poor rural people who depended on these lands. Other local complaints against the King included stopping profitable tobacco production in the Vale of Evesham.

Taxes on imported goods, called 'tonnage and poundage', were put in place. This reduced trade profits and caused opposition in towns like Worcester. The Ship Money tax in 1636 hit Worcester hard. Worcester was the sixteenth highest paying city in England. Puritans like Richard Baxter noted the growing opposition to the King's policies. People thought Charles I was trying to become a more authoritarian king.

Charles I's religious policies also caused suspicion. While the county had a Catholic minority, most people were Anglican. A growing group of radical Protestants lived in the towns. They had more social influence, for example, about public morality and keeping the Sabbath. More interest in religious ideas led to several Worcestershire towns funding lecturers to give sermons, including Baxter in Kidderminster. Worcestershire produced other notable Puritan figures, like Edward Winslow, who moved to New England with the Pilgrim Fathers. Charles's apparent Catholic sympathies, like the reforms of William Laud, were viewed with suspicion. In Worcester, Roger Mainwaring, as Dean, brought back vestments and built a marble altar.

In the early 1640s, stories of massacres of Protestants in Ireland led to rumors of Catholic plots. This caused anti-Catholic riots in Bewdley in late 1641. Local militias were told to guard against conspiracies.

The English Civil War

Worcestershire was controlled by the Royalists for most of the First Civil War. Like many parts of England, people weren't very enthusiastic for either side. Many wanted to avoid conflict. Different parts of the county had different sympathies. For example, Evesham was notably Parliamentarian, and Kidderminster also had strong Parliamentarian support. Worcester city first sided with Parliament in 1642. But it was soon occupied by the Royalists, as was the rest of the county.

In 1642, the first major fight of the Civil War happened at the Battle of Powick Bridge. This was near Worcester. A Royalist cavalry group, led by Prince Rupert, defeated a Parliamentarian cavalry group.

The Cathedral was used to store weapons during the war. Parliamentary troops ransacked the Cathedral building. Stained glass was smashed, and the organ was destroyed, along with books and monuments. The Bishopric was abolished during the Commonwealth period (1646–60).

Worcester was one of three garrison towns in the county. It had to pay for and house many Royalist troops. During the Royalist occupation, the suburbs were destroyed to make defense easier. High taxes were imposed. Many men were forced into the army.

These pressures caused great hardship for the whole county. Taxes, army demands, and raids from other areas caused much suffering. Worcestershire was vital for the Royalists. It was a bridge from Wales and Ireland to their headquarters in Oxford. Worcestershire also provided the Royalists with factories to make weapons.

Groups called Clubmen formed in west Worcestershire later in the war. Their goal was to keep both armies away from rural civilians. They resisted destruction and demands for supplies. There was also resentment towards the many Catholics in the county. The Clubmen said they would not obey any Catholic.

As Royalist power fell in May 1646, Worcester was besieged. Worcester had about 5,000 civilians and a Royalist garrison of about 1,500 men. They faced a 2,500–5,000 strong force of the New Model Army. Worcester finally surrendered on July 23, ending the first civil war in Worcestershire.

In 1651, a Scottish army marched south to support Charles II's attempt to regain the Crown. They entered the county. The 16,000-strong Scottish force made Worcester's council vote to surrender. The Parliamentarian garrison withdrew to Evesham. The Scots were housed in and around Worcester, causing new anxiety for residents. Very few local forces joined the Scots.

The Battle of Worcester (September 3, 1651) took place just west and south of the city, near Powick. Charles II was easily defeated by Cromwell's 30,000 men. Charles II returned to his headquarters in what is now King Charles House. Then he fled in disguise with help from John Talbot to Boscobel House in Shropshire. From there, he eventually escaped to France. Parliamentarian forces ransacked the city. Scottish troops fleeing capture were attacked and killed. Most were forced into labor in England or the New World.

The Restoration and Religious Changes

Religion and Dissenters

When Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660, Worcester's cathedral was in bad shape. Only three canons were alive from before the Bishopric was abolished in 1649. The cost to fix the cathedral was estimated at over £16,000.

Between 1660 and 1662, Parliament allowed many different views in the Church of England. But this ended in 1662. The Act of Uniformity required ministers to accept the Church of England prayer book. About 2,000 Anglican ministers from the Commonwealth period resigned. This included Richard Baxter of Kidderminster. Over 95 of these removals happened in Worcestershire.

In Bromsgrove, John Spilsbury was removed after the Restoration. He left the Church of England by refusing to follow the Act of Uniformity. Thomas Hall, at King's Norton, was also expelled.

Spilsbury was confined to his house, banished from the county, and finally imprisoned for his non-conformism. He did return to Bromsgrove.

Changes in the law in 1672 removed the threat of prison. They allowed some nonconformist groups to set up places of worship with a license. Presbyterians were stronger in north Worcestershire. Congregationalists and Independents were more common in the middle and southeast.

| Religious Group | Numbers of worshippers |

|---|---|

| Nonconformists | 1,325 |

| Catholics | 727 |

Tolerance for Quakers and Anabaptists was much lower. Quaker leader George Fox was arrested in 1673. However, Quakers legally set up a meeting house in Stourbridge in 1688. Anabaptists were strongest in east Worcestershire, among poorer people.

Many of Worcestershire's wealthy families were Catholic. They also couldn't fully take part in public life. Catholic worship was illegal. However, about eight priests worked in the county during the 1600s. In 1678, during anti-Catholic fears, Father John Wall was arrested. He was based at Harvington Hall. He was executed, becoming the last Catholic executed for his faith in the United Kingdom.

Charles II's Last Years

Charles II's last years were dominated by his efforts to stop the Whigs from preventing a Catholic, his brother James, from becoming king. Charles dissolved Parliament in 1681. He then tried to limit how towns could elect MPs. He changed town charters to allow the king to dismiss officials. In 1684, the charters of Evesham and Worcester were taken away. Evesham was given a new, limited voting system. King James II issued a new Charter to Worcester. It was less strict but still allowed him to dismiss council officials.

King James II and the Glorious Revolution

Catholic worship became more open during James II's rule. A chapel was set up in Worcester around 1685. Anti-Catholic riots were almost prevented in 1686.

In 1688, King James II tried to remove limits on Catholics in public life. These moves were unpopular in Worcestershire. Worcester officials were evasive when James II asked for their support. By October, the King had to calm public unrest. He restored the rights of cities like Worcester. The local council dismissed the Mayor and brought back the previous one. The same council supported the Prince of Orange in December. In 1689, James visited Worcester as a guest of Bishop Thomas. The town council went with him to visit the new Catholic chapel but reportedly refused to enter it.

Bishop Thomas was not among the seven Bishops who opposed King James' Declaration of Indulgence. This declaration aimed to bring Catholics and other Protestants back into public life. But Bishop Thomas supported the other bishops' stance. The trial of the Bishops led to James being removed and replaced by William of Orange. Bishop Thomas was among those who refused to swear loyalty to the new King. They believed a regency should rule while James was alive. Other Worcester clergy also stayed loyal to the Stuarts and were removed from the Church. John Somers, the lawyer for the seven Bishops, represented Worcester in the Parliament that confirmed William as King.

During Charles II and James II's reigns, the press was strictly controlled. These controls broke down during the 1689 revolution and were removed in 1695. Around 1690, the Worcester Post-Man was established. The Berrow's Journal claims to be descended from it.

Georgian Worcestershire (1690-1830)

Society, Politics, and Religion

Larger, industrial towns in Worcestershire grew and became crowded. Worcester was especially dense. Kidderminster expanded for carpet workers. However, wealthy people started building bigger brick townhouses, often in new areas. These areas often had better services like paved streets and lighting.

Stourport grew quickly from a small village to a fashionable town. This happened after the canal network met the River Severn there in 1770.

Great Malvern grew as a spa town in this period. It offered water cures, especially after Dr Wall promoted them in 1757. Hotels were built for visitors, and a pump room and baths were built in 1823.

Georgian Politics

Worcestershire might have been expected to support the Jacobites (supporters of the Stuart kings). This was due to its Catholic families and ties to the Stuarts. However, there wasn't much political or religious expression of these views. Still, a Whig Constitution Club formed in Worcester.

Worcester's Bishop William Lloyd was a prominent Whig. In 1710, Henry Sacheverell, a Tory who had been jailed for preaching against tolerance of dissenters, traveled through Worcester. Bishop Lloyd tried to stop church bells from ringing in his honor. When supporters broke into St Nicholas' Church, they found the bells without clappers. They hit them with iron, making a bad noise. This turned the welcome into a bit of a joke.

Pressure for political reform grew as towns got bigger. Parliamentary representation became unfair. Droitwich and Worcester, for example, had two MPs each. But Worcester was nearly ten times larger. Dudley, a similar size to Worcester, had no representation. The voting system was also very limited and open to corruption. Droitwich had only 38 votes in 1747. The low number of voters encouraged bribery. Discontent led to the Priestley Riots in Birmingham in 1791.

The 1815 Corn Law was very unpopular. It was designed to make bread prices go up. In May 1814, a public meeting in Worcester led to 6,000 people signing a petition in just two days. Petitions were also raised in Dudley and Droitwich. The next year, 8,000 people signed a second petition in Worcester.

Wealthy Landowners

The wealth of Worcestershire's landowners is shown by the building of grand houses in this period. This was a contrast to the decades after the Civil War. Examples include Croome Court, Hagley Hall, and Hanbury Hall. About 40 such properties were built or rebuilt between 1660 and 1832. Church building also showed increased wealth. These estates were supported by rents from tenant farmers and other income. Many landowners were also politically important.

Religion

The Church of England had a quiet period. But it included some church rebuilding as the population and wealth grew. Churches in Stourbridge, Smethwick, Bewdley, and Upton on Severn were rebuilt. At Great Witley, a Baroque church was built by Thomas Foley in 1735, using money from his ironworks.

John Wesley brought new energy to the Church of England from 1739. He visited Worcestershire in 1761, preaching in Evesham. Methodist Chapels were built in the 1770s and 1780s, for example, in Worcester and Stourport.

Another group, the Evangelicals, broke away from the established church. They built chapels in Cradley, Evesham, and Worcester.

The first Catholic chapel in Worcester since James II's reign opened in 1829. This was after laws removed most legal discrimination against Catholics.

Helping the Poor

People often left money to the poor in their wills. This could be small amounts for direct distribution. Or larger amounts to maintain almshouses or provide a small income to poor people over time.

Poor Relief was a tax on people with enough income. It was used to help the poor in their homes, provide clothing, or even building repairs. In Belbroughton in 1831, 68 weekly payments were made. Poor relief was only for residents of a parish. Others could be removed. For example, at Hanley Castle, over 110 people were removed between 1717 and 1835. This often involved returning pregnant women.

Worcester got a workhouse in 1703. This was to deal with rising poverty and stop beggars. Children found begging would be sent to the workhouse until they could be apprenticed at age 15.

Rural Worcestershire

While farming grew and diversified, bad harvests led to deaths or high prices. For example, in 1800, high prices caused bread riots in Worcester. Wealthy landowners often led improvements. In the 1690s, Thomas Foley introduced water irrigation in Chaddesley Corbett. This quadrupled the value of the meadows.

Worcestershire's rural communities changed as manufacturing moved out of homes and into factories. The enclosure movement also changed land rights. This removed traditional rights but allowed more commercial use of land. Enclosure began with Royal Forests in the 1600s and continued slowly in the early 1700s.

| Area | Reign | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Feckenham Forest | Charles I | 1629 |

| Malvern Chase | Charles I | 1632 |

| Aston Magna, Blockley | 1733 | |

| Alderminster | 1736 | |

| Besford Common | 1751 |

Enclosure sped up greatly between 1760 and 1820. By the end, nearly all common land in the county was enclosed. This was about a fifth of the county's land. This often caused a shift from growing crops to more profitable grazing. While landowners benefited, small farmers were not fully compensated. Many enclosures caused riots, like at Leigh in 1778. Rioters attacked the physical enclosures.

Growing wheat was common throughout Worcestershire, especially in the south. More beans and potatoes were grown. Dairy production increased, leading to a 40% growth in pasture lands. The Vale of Evesham, supplying fresh vegetables to Birmingham by rail, grew in wealth and population. Strawberries were grown from the 1870s. Asparagus, rhubarb, and salads were other common crops.

Hop production also expanded by about 50% between 1874 and 1901. This was especially true in the Teme valley. Wire frames replaced poles, and sprays helped growth. However, foreign supplies caused protests in 1908.

Selling produce and livestock at regular markets was very important. Worcester and Bromsgrove had monthly fairs. Evesham held a wool fair. Livestock markets were moved to specific sites because of the disturbance they caused. Many towns also built special corn exchanges.

Manufacturing Industries

Metal and other manufacturing industries grew in Worcestershire through the 1600s, especially in the north. Glass manufacturing, iron smelting, and coal mining were well established before 1700.

Iron production with coal from the South Staffordshire coalfield took off in 1772. This was with the building of an ironworks by John Wilkinson near Dudley. By 1794, there were 14 ironworks producing 13,000 tons of cast iron a year. Increased iron production led to the growth of the nailmaking and needle industries.

By the 1831 census, 2,751 people in Worcestershire made nails. This was mainly in Bromsgrove, Dudley, and Northfield. The industry often had low wages. Nailmakers, who supplied iron rods and bought nails back, often exploited their workers. This led to hardship and strikes.

Needle-makers were concentrated along the River Arrow, especially Redditch. Redditch also specialized in springs and hooks. The process of cleaning and sharpening needles caused metal dust to enter workers' lungs, harming their health.

Many traditional industries like tanning, milling, and brewing continued. But the cloth trade declined, outcompeted by industries in Gloucestershire and Yorkshire. Cap-making survived in Bewdley. Weavers in Kidderminster found new jobs in carpet manufacturing. The first carpet factory opened there in 1735. Skills from Brussels were brought in to compete with other high-quality manufacturers. By 1807, Kidderminster had 1,000 looms. Poor trade in the late 1820s led to riots.

Glass-making in Stourbridge grew in the 1700s. It was first known for colored window glass. In 1780, techniques from German manufacturers led to the development of cut and crystal glass.

Bone china and porcelain production started in Worcester in 1751. It used clay from Cornwall. It specialized in transfer printing, which was cheaper than hand painting. The Worcester Royal Porcelain Company got its name after King George III visited in 1788. It then opened a sales outlet in London for luxury goods.

Workers in Worcester who lost jobs in the cloth trade shifted to making leather gloves. The Napoleonic Wars helped the industry thrive by stopping French imports. Leather was cut in factories, then finished at home by women and children. Factories were set up in Sidbury. The industry suffered when trade with France restarted.

Transportation Improvements

Improvements to roads and rivers were just as important. This allowed goods to be transported and sold. The River Severn was navigable up to Bewdley. In the 1600s, the Avon and Stour rivers were made navigable. But the biggest improvements came in the late 1700s, as canals opened trade across Worcestershire and the Midlands.

In 1771, the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal opened. It aimed to connect the Severn and Trent rivers. It was supposed to link with the Severn at Bewdley. But it chose Stourport instead due to opposition. This caused Stourport to grow rapidly into a major town. The Droitwich Canal opened around the same time. Work began on the Worcester and Birmingham Canal. Landowners strongly opposed this. But Parliament's permission in 1791 was met with celebrations in Worcester. However, it wasn't very profitable.

Victorian and Edwardian Worcestershire (1830–1914)

Worcestershire's population grew quickly. It went from 220,000 in 1831 to 488,355 in 1901. Infant deaths were high for most of the century. Epidemics were common. Housing was especially bad in industrial areas like Dudley. A health inspector reported in 1851 that Dudley was particularly unhealthy.

| Settlement | 1831 | 1901 |

|---|---|---|

| Broadway | 1,517 | 1,414 |

| Pershore | 5,275 | 4,825 |

| Bromsgrove | 8,612 | 14,096 |

| Worcester | 27,641 | 49,790 |

| Great Malvern | 4,150 | 19,131 |

| Halesowen | 9,765 | 38,868 |

| Yardley | 2,488 | 33,946 |

Small towns like Bewdley and Pershore stayed the same size or shrank slightly. Larger towns like Bromsgrove and Worcester roughly doubled. But in the north, industrial towns like Halesowen, Dudley, and Yardley grew hugely.

Spa towns were created. Great Malvern quadrupled in size because it was promoted as a spa town. Tenbury Wells didn't have the same success. In the 1880s, John Corbett invested salt profits into spa facilities in Droitwich. He opened St Andrew's Brine baths in 1887.

Politics and Reform

When the Reform Bill was rejected in 1831, a riot broke out in Worcester. The Mayor was hit by a stone. He called in soldiers to stop the disturbance. The riots were about the lack of Parliamentary reform and dissatisfaction with local government. Local government was run by self-appointed town leaders.

Protests against high bread prices and for political reform often combined. In 1842, a meeting in Worcester said that a representative Parliament would never have supported the Corn Laws. The Mayor stopped the meeting from supporting the People's Charter, which called for all men to vote.

After Chartism's political defeat in the 1840s, a movement started to help working people own land. Money was raised to fund small villages of Chartists with land. Two were in Worcestershire, at Dodford and Lowbands. But the plan wasn't sustainable and was shut down.

In 1835, the Municipal Reform Act created a system of elected Mayors, Aldermen, and councillors. Only men with certain property could vote. In Droitwich, the town clerk refused to hand over documents to the new authority. Other towns slowly got new borough administrations. Bromsgrove became an urban district in 1858.

Political corruption continued in Worcester throughout the century. Votes were bought with bribes, like money or beer. Poorer people sometimes saw this as important extra income. Extending voting rights made bribery very expensive. Despite the Corrupt Practices Act in 1883, bribery continued. A Royal Commission in 1906 found that about 500 people in Worcester still sold their votes.

Town facilities improved. New town halls were built, and gas street lighting was installed. Libraries and public parks were created, especially in the late 1800s.

Education

National laws drove efforts to provide education. Local areas often provided free education for the poor through donations. But this was uneven. The Church of England National Society started providing voluntary schools. After the Education Act 1870, local School Boards filled the gaps. Schooling became compulsory in 1880. Some older grammar schools changed their management. After the Education Act 1902, local authorities started opening secondary schools.

Independent schools were also established, like Malvern College in 1865 and St Michael's College in Tenbury in 1856.

Technical education grew through Mechanics Institutes. This led to Worcester's School of Art and Science opening in the 1890s.

The Poor Laws

National legislation in 1834 required parishes to combine resources to support the poor. This created new Workhouses across Worcestershire. For example, 34 parishes around Pershore built a Workhouse for 200 poor people. By 1894, 11 unions across Worcestershire provided for 7,228 people in workhouses. Punishments for breaking rules could be harsh.

Religion and Church Building

| Church | Architect | Year |

|---|---|---|

| St James the Great's Church, Blakedown | G. E. Street | 1866 |

| St Peter's Church, Cowleigh | G. E. Street | 1865 |

| St John the Evangelist's Church, Stourbridge | G. E. Street | 1860–61 |

| St James' Church, West Malvern | G. E. Street | 1871 |

| St Laurence, Alvechurch | William Butterfield | 1859-61 |

| St Mary, Sedgeberrow | William Butterfield | 1867-68 |

| St Peter and St Paul at Upton on Severn | Arthur Blomfield | 1878-79 |

| St Michael, Smethwick | A.E. Street | 1892 |

| Worcester (restoration) | A.E. Perkins, Sir Giles Gilbert Scott |

With the rising population and wealth, many Anglican churches were built, rebuilt, or restored. This was driven by the Oxford Movement and the evangelical movement. Special effort was made to strengthen the church's work in the industrial north of Worcestershire. Worcester Cathedral's exterior and windows were also restored. New churches were built, often in the Gothic style, by famous architects.

Nonconformists also expanded their chapels, which started to look more like churches. Catholic churches began to be built after restrictions were removed in 1829. At Hanley Swan, the Church of Our Lady and St Alphonsus was built by descendants of Thomas Hornyold, who helped Charles II escape. Catholic churches in the county often had more funding than in other areas.

Industry in the Victorian Era

Industry dominated the northern parts of the county, known as the Black Country. Coal mining took place around Dudley, Stourbridge, and Netherton. Most mines were shallow. The coal was soft and not ideal for most industrial uses. Still, in the Dudley area, annual production was around 700,000 tons, employing 2,500 people. Another area around the Wyre Forest also produced coal. Ironstone was also mined extensively.

The iron industries in the north made chains, anvils, and many tools. Nail making was common in some areas, including Bromsgrove. Scythe-making in Belbroughton continued but declined.

In Kidderminster in 1838, 24 carpet manufacturers controlled about 2,000 looms. These were lent to workers who used them at home. Over the century, this changed, and looms were used in factories. In 1841, 138 needle and fish hook makers were in Worcestershire, mostly in Redditch.

Droitwich continued to produce salt. Workings were extended to Stoke Prior, extracting salt from 200 feet deep.

In Worcester, the Royal Porcelain Company faced competition. It tried to counter this by moving to more specialized production. A similar pattern was seen in the glove industry. By 1851, it employed about 2,500 glovemakers, much less than before. Most worked at home. These jobs moved to factories with new sewing machines.

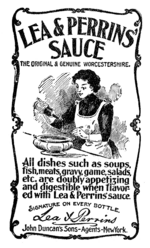

Lea & Perrins Worcestershire sauce began to be made and bottled in Worcester around 1837. It was first made by two chemists, supposedly from a recipe given by a "Nobleman of the County." Production expanded. A new factory opened in 1897, which helped with exports to the USA.

Transportation

The River Severn's navigability was improved with new locks after a Parliamentary Act in 1842. Roads also improved through the Turnpike trust system. This also helped the stagecoach network. For example, Worcester was connected to Liverpool in eleven hours from 1832.

With steam power, mass transportation moved from canals to rail. Railways grew slower in Worcestershire than elsewhere. The Birmingham and Gloucester Railway opened in 1840. But it didn't pass through Worcester due to opposition from landowners. The route through the Lickey Hills was controversial because of the very steep Lickey Incline.

Worcester was connected to the rail network ten years later. It got a route to London in 1852. Northern Worcestershire was most closely connected by rail. This was due to its iron, steel, coal, and other industries.

The arrival of railways often caused big celebrations. A breakfast, carnival, and ball were held in Tenbury Wells in 1864 when it was connected to the Kidderminster line. The benefits could be huge. At Great Malvern in 1861, the line from Worcester brought 3,000 visitors in the first year.

Agriculture in the Victorian Era

The 1830s and 40s were hard for rural Worcestershire due to high prices from the Corn Laws. The 1850s and 60s were more prosperous due to demand from towns. Bad harvests in the 1870s were followed by cheap food imports from the USA.

Wheat was the main crop but declined after the 1870s. Beans and potatoes became more important. Dairy production increased, leading to a 40% growth in pasture lands. The Vale of Evesham, supplying fresh vegetables to Birmingham by rail, grew in wealth and population. Strawberries were grown from the 1870s. Asparagus, rhubarb, and salads were other common crops.

Hop production also expanded by about 50% between 1874 and 1901, especially in the Teme valley. Wire frames replaced poles, and sprays helped growth. However, foreign supplies caused protests in 1908.

Sales of produce and livestock through regular markets were very important. Worcester and Bromsgrove had monthly fairs. Evesham held a wool fair. Livestock markets were gradually moved to specific sites. Many towns also built dedicated corn exchanges.

Rural Society

Villages in this period had their own shops and crafts, like blacksmiths and carpenters. Day laborers provided horses and carts. Corn mills were very important for making flour. Local traditions like Maypole dressing and 'Thomasing' (where old women begged for alms) were common.

Pubs were a central point for communities. Beer production was a big part of the local economy. Village sports grew, especially football and cricket clubs in the 1880s and 90s.

Large estate houses dominated rural parishes. They were centers of authority and employment. Hagley Hall, for example, employed 21 servants. Their owners increasingly included families who made money in industry. They often bought country homes to show their status. Witley Court was bought by the heir to the Dudley's, William Ward.

Houses were built and extended, many in the Gothic style, like Madresfield Court. Astley Hall was built in a Jacobean style in the 1830s. Bricklehampton Hall was built in an Italianate style in 1848. Chateau Impney near Droitwich was built by salt magnate John Corbett for his French wife.

Twentieth Century (1914-2000)

The 1900s saw more population growth, but at a slower pace. Rural population was denser in the north. Industries shifted away from manufacturing. Manufacturing jobs declined from 40% in Worcestershire in 1931 to 25% across Hereford and Worcester by 1980. Service jobs were the main employers, growing from 45% in 1931 to 60% in 1980. Only 5% of the population worked in agriculture. Female employment increased, but two-thirds of full-time jobs were held by men in 1980.

Heavy industries were dominant early in the century. Metals and engineering dominated the north of the county, in Dudley, Halesowen, Oldbury, and Stourbridge. Carpet manufacturing dominated Kidderminster. The glove industry in Worcester was already declining but still provided jobs. Dents, the main employer, left Worcester in the 1930s.

Worcester continued to develop metal industries. Bromsgrove gained a major drop forge plant, Garringtons, after World War II.

Commuting became common. By 1961, half of Halesowen's employees traveled outside the borough for work.

Mixed farming remained important. Fruit and vegetables dominated in the Vale of Evesham. Hop production in the Teme Valley declined as beer production became more centralized.

The Great War

Worcester was a center for recruiting soldiers for the First World War. The Worcestershire Regiment was based at Norton Barracks. The regiment fought in early battles, notably at the Battle of Gheluvelt in October 1914. This battle stopped the German army from reaching Belgian ports.

The new Vicar of St Paul's in Worcester, Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy, encouraged men to enlist. He became an army chaplain, known as 'Woodbine Willy'. He brought cigarettes to soldiers and risked his life, earning a Military Cross. Shops in Worcester collected cigarettes for him. His war experience led him towards pacifism and Christian Socialism. After the war, he left his Worcester parish but kept a house in the city.

Boundary Changes

The county's borders changed further. In 1966, parts of Birmingham were joined with Worcestershire to form Warley. This area stayed until 1974.

Hereford and Worcester

In 1974, Worcestershire merged with Herefordshire to form a large county called Hereford and Worcester. In 1998, it went back to the original historical counties. Some areas like Halesowen, Stourbridge, and the Dudley area, which were part of northern Worcestershire, became part of West Midlands metropolitan county. Yardley had already become part of Birmingham in Warwickshire. So, the county after 1998 is not exactly the same as before 1974.

|

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |