History of the Coast Salish peoples facts for kids

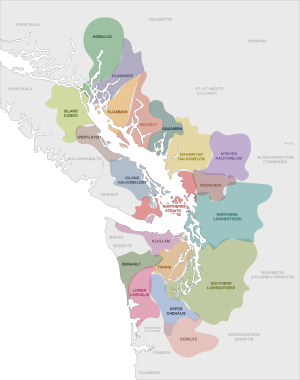

The History of the Coast Salish is about the past of a special group of Native American people. They live along the Pacific coast of North America. These groups share a common culture, family ties, and languages. Their history goes back thousands of years. Old tools and items show that their way of life has been quite similar for over 7,000 years in some places.

People have lived in the area of today's Coast Salish for more than 10,000 years. This area includes the coastal parts of British Columbia in Canada and the states of Washington and Oregon in the USA.

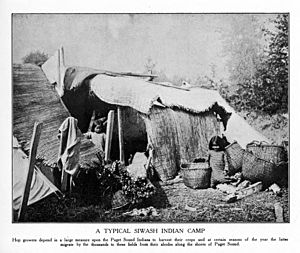

The Coast Salish people mainly got their food by fishing, especially for salmon. They also hunted animals and gathered plants. New studies show that some groups lived in villages that they used at different times of the year as early as 2000 BC.

When Europeans first arrived around 1775, they brought new diseases. Smallpox was one of the worst. It caused many Salish groups to lose a huge number of people. In 1790, Great Britain and Spain agreed not to build trading posts on the coast. So, forts were first built inland, along the Columbia River. They didn't reach Vancouver Island until more than 50 years later.

Because of this, canoes and old trade routes, like the Grease trails, became very important. They were used for trading otter and beaver pelts. In return, the Salish received metal tools and weapons. These new items greatly changed who had power among the tribes.

In 1846, the Salish lands were split. The northern part went to the British Hudson's Bay Company. The southern part went to the USA. The USA pushed the Native Americans off their lands more forcefully. They made them move to reservations using military power. In British Columbia, each group considered a "tribe" got its own small Indian Reserve. In the USA, larger "reservations" were set up for several tribes to live together.

Both countries tried to force the Native Americans to change their culture. The USA used more methods like mixing populations, privatizing land, and economic pressure. Both countries also tried to destroy Native American cultures. They banned traditional practices and set up school systems that forced children to adopt European ways. Today, many tribes have successfully brought back their cultural heritage. They are also working to gain more control over their own affairs.

Contents

A Look at Early Coast Salish History

The early history of the Coast Salish is mostly known through archaeology. Written records only started when Europeans arrived in the late 1700s. We also learn from oral traditions, which are stories passed down through generations. And we can study Culturally Modified Trees, which are trees that show signs of being shaped by people long ago.

The Coast Salish people were semi-nomadic, meaning they moved around but stayed in certain areas. They lived mainly by catching salmon. By 1600 BC, they began to live in a more settled way, changing the landscape around them. They also had large villages that were used as winter homes for hundreds of years.

Coast Salish societies had different social groups. There was a leading group, often called nobility. Then there was the general population. And there were slaves, who were usually war captives or their descendants. Slaves were also traded. Important gifts were exchanged among the leading groups. Like being part of the nobility, the role of chief was usually passed down in certain families. But a chief could lose their position.

The region gets a lot of rain, creating Temperate Rainforests. These forests provided wood for many things. They supplied material for Totem Poles, which could be over 50 meters tall. They also provided wood for houses, like early plank houses. And the forests gave food, clothing, and blankets. Metal was very rare in this area.

Strong, seaworthy canoes allowed for battles along the coasts. They also made long-distance trade possible. European fur traders and explorers used these same trade routes and waterways. However, they also brought new diseases. Smallpox greatly reduced the Salish population as early as 1775. This time also saw more warfare. Northern coastal groups raided villages, and European weapons made these attacks even more intense.

In 1846, the USA and Great Britain divided the large Oregon Country along the 49th parallel. This split traditional territories, family ties, and trade routes. New settlements led to conflicts, especially in Washington, like the Puget Sound Wars. In Canada, Indian reserves were created, scattering communities. In the United States, several tribes were often grouped together, forming new "tribes."

At first, the Salish played an important economic role in British Columbia. But laws soon pushed them out of most jobs. In the USA, they were often moved to less desirable areas. Both countries tried to force the Salish to change their culture. This started with missionaries trying to convert them to Christianity. The Salish developed their own spiritual practices in response. Governments banned important cultural expressions. They also stopped all native inhabitants from having the right to vote. This even led to children being forced into boarding schools. The Canadian government apologized for these schools in 2008. During this time, the population dropped sharply. Most languages were lost. Many people moved to cities, so now most Coast Salish live in urban areas.

Things began to change when tribal leaders won legal cases in the highest courts. With more open borders and some tribes becoming wealthier, people started to remember their shared culture. This led to a partial rebirth of the Salish community. Many groups are still fighting to be officially recognized as tribes. This recognition is needed to begin talks about their self-governance and land rights. Tribal groups are working together. Borders are being marked, and rights are slowly being given back.

For many decades, the USA tried to divide tribal lands into private plots. But most Canadian reserves remained tribal property. Since 1993, British Columbia has tried to privatize land in exchange for larger reserves. This is part of the BC Treaty Process. However, only a few agreements have been made so far. Since 2007, it's been unclear if this process will continue.

Early Human Presence and Cultures

We learn about the early history of the Coast Salish and their ancestors mostly from archaeology. Later, oral traditions also tell us stories. In British Columbia, about 400 building permits are given out each year. This is for about 23,000 archaeological sites. This often causes problems. Most historical clues are hidden underground or in shell middens. These shell mounds can be several meters high. It wasn't until 1995 that a tribe in British Columbia, the Nanoose, got a say in how archaeological sites are managed. Even with little funding at first, research in recent decades has found amazing things. Washington state has a similar situation. In 2003, a report found 14,000 archaeological sites there. These range from entire villages to Culturally Modified Trees.

In the very early days, the landscape was changing a lot. Glaciers, melting ice, shifting coastlines, and lower sea levels shaped this time. There were also tsunamis, and the land moved up and down as huge ice masses melted. Many artifacts from this time are probably lost forever. This might explain why we find few artifacts from before 8000 BC. But some places that were never flooded have older items. For example, artifacts from the 9th millennium BC were found on Dundas Island.

One of the oldest sites in British Columbia is near Namu. This area was settled between 8000 and 3000 BC. People lived there semi-permanently or permanently. They made tools from coarse volcanic rock. Recent studies suggest they used boats.

Traditionally, the Coast Salish believe they have always lived in their current lands. They have many creation stories. These often feature animals in human form, creators, or ancestors of today's tribes. There's also the idea of a "transformer" who shaped the land, animals, plants, and social rules. These stories often include memories of when they first arrived and of a great flood.

Milliken Phase (around 7500 BC)

The Stó:lō, who are part of the Salish, also believe they have always lived in their current home.

The Milliken Phase (7500-6000 BC) is the oldest period we know about from archaeology. The only site found is 4 km above Yale. Tools from this time include leaf-shaped, egg-shaped, and crescent-shaped blades. There are also burins, thin scrapers, and items made of soapstone. Argillite was the most common stone used. Basalt, quartz, and obsidian were rare. Some burnt cherry pits show when people were there. Since this was also the time of the salmon migration, it's likely they were already catching salmon. Some obsidian pieces came from Oregon, 400 miles away. This shows there was long-distance trade.

The Mazama Phase (6000-4500 BC) is named after a huge volcanic eruption that formed Crater Lake in Oregon. Evidence for this phase is found at Yale and also at Hope. New tools appeared, like egg-shaped hand axes, planes, and wedges. Tiny stone blades called microliths are also found. Basalt became more common than argillites. Even in this early phase, we can see cultural differences. The north was more connected to Alaska, and the south had ties as far as Oregon.

The Eayem Phase (4000–1100 BC) is clearly found only in Agassiz. A pit house was found there, which is the first sign of permanent homes (around 3000 BC). New tools appeared, like projectile points (whether pinched or notched), drill bits, and grindstones. The oldest village site (around 3000 BC) is the Paul Mason site in Kitselas Canyon on the Skeena River. It shows signs of a society without strict social classes. This village was lived in from 1200 to 700 BC. These houses were built close together in rows, much like what European explorers saw in the late 1700s. But the early houses were lighter, and their sizes didn't vary much. The oldest art pieces are from around 2500 BC. The oldest burial sites are also from this time. Around 1500 to 500 BC, the first war clubs made of stone or whale bone appeared.

The Baldwin phase (1100-650 BC) is found again in Milliken, and also in Esilao and Katz (Sxwóxwiymelh in the land of the Chawathil). This phase is known for microblades, small projectile tips, mortars, and pestles. Jewelry like rings, earrings, beads, and pendants appeared. Art with figures also became common. This phase is seen as a step before the Marpole culture. More fragile items like baskets, woven hats, ropes, and mats are found. These materials were also used for clever boxes for storage and transport. Most importantly, they were key for preparing and storing food. Pottery didn't exist, and clay was used less and less.

From about 500 BC, post houses became common. These became a key feature of the west coast culture. It's likely that the Rainforest had grown large enough trees. Also, woodworking skills were advanced enough to work with giant trees. By 1000 AD, people often tried not to kill the giant trees when using them. Stone sculptures also appeared for the first time around this period. Fifty of these are now in the Royal British Columbia Museum.

On the south coast, from around 500 AD, there is evidence of lip piercings. But these disappeared there, unlike in the northern coastal areas where they are still a tradition. A type of ear coil also lasted from around 1500 to 500 BC. The mysterious Whatzits, which are soapstone objects, might also be from this time, but their use is unknown. Strings of beads were used as jewelry. Sometimes, rings made of copper were found. Copper was rare and valuable, coming from Alaska. Such finds show a wide-reaching trade system. These goods might have been used to show off wealth, which likely connects to the rise of a leading class, the later nobility.

The Skarnel phase (350 BC to 250 AD) is marked by the disappearance of microliths. Sites from this phase include Esilao, Katz, Pipeline, and Silverhope Creek.

By the Emery phase (250-1250 AD), pipes appeared, probably around 500 AD. However, tobacco was only smoked on the south coast. In the north, it was mostly chewed. In the north, tobacco was grown in gardens. But gardening for food didn't become widespread. At the same time, spindle whorls and other tools for making blankets appeared. These blankets were likely made from the hair of dogs and Mountain Goats. Dogs were kept like sheep in Europe, especially on the Gulf Islands.

The Esilao phase (1250–1800 AD) ended with the first European contacts. This phase is known for small projectile tips and certain types of forts. The huge mussel heaps from this time give many clues about the society. They contain shells, ash, fire-cracked rocks, and animal bones. Along the entire coast, from about 3000 to 2500 BC, stone, bone, or antler tools were used. From about 1500 BC, a society that stored more food seemed to develop, relying mainly on salmon. The first permanent winter villages are from 1200 BC. Large shared buildings appeared around the time of Christ's birth.

In the delta of the Fraser River, important sites include St. Mungo, Glenrose, and Crescent Beach. Mussels were very important here. Fish were more important than game or sea mammals, especially salmon and the starry flounder. However, hunting land animals also remained very important, followed by seals.

Marpole Culture (400 BC to 400 AD)

Today's Coast Salish people can trace their roots back to the Marpole culture. This culture already had clear social classes. People lived in plank houses that held many families. They fished for salmon and preserved it. They created rich carvings, often very large. And they had complex ceremonies.

Because salmon fishing was so important, people once thought the Marpole culture came from the lower Fraser Valley or the Plateaus. But it seems the Marpole culture developed right there in the region. This culture is named after a site in today's Vancouver. It was once on the coast, but now the Fraser River's deposits have moved the coastline west. The village was built on a shell mound, which was 3 to 4 meters high and covered several hectares. The South Coast reached a peak of complexity during this time. Permanent winter settlements are proven, and by the time of Christ's birth, plank houses or longhouses existed. Burial sites show clear differences in social status.

Harpoons with barbs replaced older types of harpoons. The amount of decorative art greatly increased, such as stone figures. An important Marpole site is Beach Grove, a winter village in the Fraser Valley. It has depressions from houses that were large but haven't been fully measured. Children's graves there are remarkably rich. For example, they contain Dentalia (shells) and especially copper, which was extremely rare and valuable then.

Around 400 BC, a society developed where people gained respect by showing off their wealth. Between about 500 and 1000 AD, many South Salish groups are identified by stone mound graves called cairns. There are hundreds of these around Victoria and Metchosin. At that time, society likely still focused on rank or prestige. It wasn't until around 1000 AD that a small group of powerful people controlled not only inherited status but also power and resources.

Life Around 1800

Traditional Ways of Life

Like other groups on the Pacific coast, the Salish tribes relied heavily on sea animals. But unlike the Nuu-chah-nulth, they didn't hunt whales. Salmon were extremely important, as they swam up the rivers each year to lay eggs. Other fish like Herring and Halibut, as well as birds and land animals, were also eaten. However, not everyone could hunt everywhere. Certain families owned their reef nets and specific gathering areas, like those for horse clams. These were reserved for the "nobility." Similar rules applied to building houses, hunting, and gathering plants like berries and grasses. Family groups might move to certain areas that "belonged" to them, depending on the best time to harvest plants each year.

It's been known for a while that the Salish were not just hunters and gatherers. They were also farmers who stayed in specific areas. They moved with the seasons, following nature's cycles. For example, they planted camas, a plant with blue flowers from the Agave Family. Its bulbs taste like sweet baked tomatoes or pears. The Salish used two types: the Common Camas (Camassia quamash) and the Large Camas (Camassia lichtlinii). Over centuries, growing and caring for the soil changed the landscape, making it look like a park. Harvesting was also a good time for social gatherings in camps and for strengthening the community with rituals.

They used fire on purpose to create open, treeless areas. These areas were needed for growing camas and potatoes, which they adopted around 1800. The Garry Oak (Quercus garryana) was especially important. It grows between British Columbia and California, but it thrives best around Victoria. Around 1800, this system covered about 15 square kilometers in the area of today's city.

Seasonal movements shaped their year. They spent winters along rivers, where larger groups gathered. The most important ceremonies and celebrations took place from October/November to February/March. In spring, they went fishing to restock their food. Fish was air-dried, smoked, or eaten fresh, but never salted. Dried fish was also a key trade item. Roots, shoots, and berries were equally important food sources.

During the summer, they collected wood. They also cut wood for house poles, planks, canoes, totem poles, weapons, and tools. They made headgear and clothing from wood too. A special white-haired dog breed provided hair for blankets. Simon Fraser saw these dogs in 1808. There were also "camp dogs" that were like Coyotes, guarding villages and camps. In July and August, when salmon swam upstream, fishing was the main activity. In late summer, they returned to the mountains.

Their movements were guided by a spiritual calendar called the "system of the thirteen moons." This calendar set the times for economic activities like fishing and harvesting, along with ceremonies and teaching. Each lunar month had specific places to live, ceremonies, and times for learning.

To avoid arguments, tribes claimed traditional territories. These lands ensured their survival during their yearly travels. So, these areas were made up of many smaller "settlement chambers" for a life that was temporarily nomadic. In bad years, long-distance trade, using coasts for large trading canoes, could save lives. They could also export camas, and later tomatoes or potatoes, to areas where they couldn't grow. The benefit of this lifestyle was that there were almost no crop failures. Even if crops failed in bad years, they could rely on the sea. To ensure access to these areas, family lineage was important. This meant certain areas or tools could only be used by people related through a specific family line. Because of this, the number of Coastal Salish people was very large, though we don't have exact numbers. Explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark said in 1805 that the population was as large as "any part of the United States."

Other fruits were also grown, changing the landscape. But until recently, this wasn't seen as farming. For example, the Cowichan brought Wapato roots (Arrowwort) to the Gulf Islands. There were also large wapato fields along the Columbia River. Clark noted on November 22, 1805, that wapatos tasted like Irish potatoes and could replace bread. The Kwagewlth kept stone-walled gardens of Pacific Silverweed and clover fields at the mouth of the Nimpkish River. The Sto:lo regularly burned land to help berries grow better. Other cultivated lands grew Cranberries, Gooseberries, Rubus spectabilis, Rubus parviflorus (Thimbleberry), Wild Onions, Strawberries, Cow Parsnip (also called Indian Celery), carrots, "crab apples," blueberries, and black currants. The lines between farming, gardening, and simply keeping areas clear for certain plants (like by fire or stone walls) were often blurred.

George Vancouver saw large camas fields on southern Vancouver Island and at Puget Sound. He reported, "I could not believe that any uncultivated land was ever discovered that gave such a rich picture." The fact that the population was quite small due to recent smallpox outbreaks likely added to this impression. Around 1913-1916, the McKenna-McBride-Commission still believed that only uncultivated land could be Indian land. In many places, they refused to add garden land to the reservations.

Societies and Social Classes

Around 1800, the social hierarchy of the Coast Salish was much clearer than in the inland areas. It also became stricter from south to north. Besides the leading group, who controlled resources, there were ordinary tribal members and slaves. The idea of ownership covered everything. Not only objects, houses, and people could be owned. Fishing spots for salmon, places in general, rituals, ceremonies, songs, and stories could also be owned. Not everyone was allowed to know these things. War was mainly a way to gain wealth, for example, by taking slaves. Slaves helped the upper class by creating and maintaining their living means. Still, they lived under the same roof as their owners. They could also gain spiritual power.

Sometimes there were large settlements with over a thousand people. Houses usually held several families. They shared a common household but divided it among themselves. These houses were decorated with symbols, like totem poles and painted walls. The masks of the coastal peoples are also famous. Often, family lines traced their history back to a common ancestor. This ancestor would appear in ritual objects. Society was organized by these special family types, not mainly by tribe. So, family relationships determined the family's dialect. They also decided who worked together and who shared resources. These family ties went far beyond the local house group and village into other communities. The village, however, was important for certain ceremonies.

While the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian are described as matrilineal (tracing family through the mother), among the Wakashan and Salish, family lines were traced through both the father and mother. Inheritance was not common among the coastal Salish. Among all Salish, the levirate (a man marries his deceased brother's widow) and the sororat (a woman marries her deceased sister's widower) were common. This helped keep relations strong between families connected by marriage. Family relationships were always two-sided, and marrying close blood relatives was forbidden. These wide-ranging family ties were extremely important. Local relationships also existed within the family, household, local group, and winter village. The extended family is still an important emotional and economic support today. Family unity remains the basis of political life.

The chiefs of the tribes were mostly men, but women were often heads of their households. Leadership depended on a person's ability to gain and use spiritual power, and on their personal skills. There was no formal, higher authority. Related to this was the idea of redistribution. This meant sharing wealth, mainly through the potlatch. In a potlatch, people would give away valuable items to show off their status and to balance wealth. Therefore, government bans on potlatches, which lasted until 1934 in the USA and 1951 in Canada, were a direct attack on a core part of Native American cultures.

Trade and Exchange

Trade was important, but not always like European trade. Journeys were for exchanging goods. They also helped build and strengthen family ties, which could be used even after a long time. So, the coastal Salish had places to stay almost everywhere in their large living area. This made trade easier. However, this knowledge was "private" and belonged to only one family at a time. The lower class had much less freedom to travel and didn't have such knowledge.

There was a lot of trade in Camas bulbs. These bulbs were 4–8 cm wide and could weigh over 100 grams. Trade was especially strong with the Nuu-chah-nulth. This was because most of the desired camas grew in the drier, warmer south of Vancouver Island. Even before white settlers arrived, Native Americans grew tomatoes and potatoes. They probably got these from the first forts of the Hudson's Bay Company. Beans were also sometimes planted, but they didn't seem to be traded.

Other important trade goods included otter and beaver pelts, fish oil and fat (especially the oily fat of the candlefish). Timber for plank houses and for the fur trading companies' forts was also traded. Additionally, there were blankets. Some were made from goat hair. Around the Juan de Fuca Strait, blankets were often made from specially kept dogs. Dogs were likely kept like flocks of sheep. They provided white and dark fibers for blankets, mats, baskets, and clothing, which were widely traded. When many trade connections were cut, blankets became an important item. The Hudson's Bay Company soon traded them. They were also offered as payment for land when reservations were created.

Raids and looting by tribes north of the Salish, especially the Haida, Kwakwaka'wakw, and Tlingit, may have greatly harmed trade in some years. These raids became worse with the arrival of the first fur traders and a steady supply of weapons. We don't know much about how these raids changed the economies of the northern tribes.

Europeans and Americans Arrive

First Meetings and Disease

The first contacts with Europeans happened with the southernmost Salish tribes. In 1775, two Spanish ships arrived. At least one, the Santiago, led by Bruno de Hezeta, likely brought smallpox to the Quinault. This terrible smallpox epidemic is thought to have killed at least one-third of the Native Americans on the Pacific Coast. Among the Salish in what is now the United States, the losses were probably much higher. They were so weakened that they could barely defend themselves against raids from northern peoples, who were less affected at first. The disease kept returning, like in 1790. A ship led by the Spaniard Manuel Quimper visited the Beecher Bay First Nation and spread the disease. Among the Lower Elwha Klallam alone, at least 335 skeletons were found at Tse-whit-zen in 2005. Trade routes on land and the crews of fur trading ships quickly spread the disease. For example, among the inland Salish of the Flathead, Spokane, and Coeur d'Alene, a "great disease" happened in 1807-1808. But it wasn't until the 1853 epidemic that we can be sure it was smallpox.

Large-Scale Immigration

At first, very few settlers lived in the region, even when California was filled with gold seekers. Then, early settlers came to Washington and Oregon. In 1850, a count showed 1,049 white residents in what is now Washington. By 1860, there were 11,594. With the Gold Rush on the Fraser in 1858, the population further north also grew very quickly. Thousands of gold prospectors, mostly armed and from California, searched the region. They displaced or killed an unknown number of Native Americans. The "old settlers" quickly became a small group. This forced the British colonial government to act. It strongly encouraged immigration from Great Britain. This pushed the Stó:lō or Tait even closer together. Others were sent to tiny, remote reservations.

Governor Douglas had already started a reservation policy. The first treaties with tribes around Victoria or Nanaimo showed this. In 1861, he told the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works to set up reservation boundaries. The expansion of Indian Reserves was to be decided by the Native Americans themselves. This fairly mild policy ended in 1864 with Joseph Trutch becoming Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works.

Such a mild policy in the United States lasted only until 1846 or 1855. When the Hudson's Bay Company, which profited from Native American trade, had to leave in 1846, new interests took over. The Oregon Territory, or from 1853, the Washington Territory, was not very important at first. However, the first settlers from about 1850 clashed with the Native peoples. This was due to their land claims and harsh actions. The Native Americans had mostly dealt with traders before, some of whom had even married into their families. This system was quickly destroyed. The settlers' land claims were based on the Oregon Donation Land Act of 1850. This law allowed almost any settler to claim up to 320 acres of land per person. During the five years it was active, about 8,000 claims, totaling 3 million acres, went to white settlers through this act. The Native Americans were dispossessed without any discussion.

In 1855, several treaties were made. But the terms were so bad that the Yakima and the Puyallup, for example, rebelled. But large troop deployments stopped the uprisings (1855-1858). In the case of the Chinook, this led to them almost disappearing. The reservation of the Cowlitz was simply sold (see Treaty of Point Elliott). Also, against the custom of local groups, "tribes" were formed that had not existed before. Governor Stevens said, "When gathered into large bands it is always in the power of the government to secure the influence of the chiefs, and through them to handle (manage) the people." Like others at the time, he believed Native Americans should live on reservations, fish, and become farmers with the help of white residents.

Epidemics and Missions

Worse than land disputes were the epidemics from the beginning. The smallpox epidemic of 1775 devastated the Salish. Perhaps in 1801, but definitely in 1824 and 1848, measles followed. Then again in 1837 and 1853, and in 1862, smallpox returned. Other diseases unknown to Native Americans, like flu and tuberculosis, were even more deadly. Protection efforts by some missionaries and doctors, like in 1853 and 1862, only helped a little. Many Salish around Victoria and Puget Sound survived. But this time, the North was hit hard. Still, mission stations benefited from these disasters. Many shamans, medicine men, elders, and healers died. This loss of cultural knowledge, plus the belief that their own powers were too weak, caused many Salish to convert to Christianity.

The first missionary was Modeste Demers, a Catholic missionary who reached Fort Langley in 1841. In 1861, the St. Mary's mission, run by the Oblates, was set up on the Fraser River. Bishop Paul Durieu even managed to create a kind of religious state among the Sechelts. However, their numbers had fallen from about 5,000 to 200. In 1859, the Methodists joined them in Hope.

But the southern Salish tribes in Washington were also greatly reduced by epidemics. Some tribes disappeared forever, like the Snokomish. Catholics and Methodists started missions as early as 1840 and 1850, but with little success at first. It was only after the "Indian Wars" that missions saw more success.

Competition between different Christian groups created new divisions among the Salish. The leaders of each community watched over the lives of their young people. They changed the traditional watchman system into a way to control and punish. They also disliked marriages between people of different Christian groups. This further weakened the Coast Salish's family-based communication system. Different Christian groups, and thus tribes, kept more to themselves.

Reserve Policy and the Trutch System

British Columbia's policy towards Native Americans was often harsher than the government's in Ottawa. This was partly because gold miners from California moved there. These miners, with their lack of fairness, even pushed friendly tribes into rebellion, like in the Fraser Canyon War. This war ended with almost no bloodshed for the Native Americans. Ottawa thought 160 acres of land per family was fair. But the provincial government would only give 25 acres. In 1875, an Indian Reserve Commission was created to solve the land issue. The idea was to make a deal with each individual "nation." But this meant each person, regardless of family ties, was assigned to a "tribe." This tribe was then given a territory, usually not one continuous area but a collection of specific spots.

The reservations created were to be held in trust. Their size could be changed based on population. In 1877, Gilbert Malcolm Sproat became the only Indian Reserve Commissioner. But he was removed in 1880 for giving too much land. Peter O'Reilly took over until 1898. The federal government often disagreed with provincial policy. In 1908, the commission began to break up. In 1911, the case was supposed to go to the Supreme Court, but the province refused to cooperate. On September 24, 1912, the McKenna-McBride Commission was set up. From 1913 to 1916, the commission visited the reservations. It recommended reducing 54 reserves by a total of 47,000 acres. After protests, this was reduced to 35 affected reservations or 36,000 acres. The remaining 733,891 acres were divided into over 1,700 pieces of land.

Fighting for Rights

The Salish were among the first to try to work within the new political system, which was unfamiliar to them. In 1906, a group traveled to meet King Edward VII in Britain. They wanted to argue for their land claims. Chiefs of the Lillooet met with Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier in 1912, but he lost the next election. In 1913, the Nishga Petition was sent to London. But no action could be taken from there because Canadian courts had to deal with it first.

After realizing their efforts were failing, most tribes decided to connect with each other. In 1909, the inland tribes formed the Interior Tribes of BC. The coastal tribes formed the Indian Rights Association. These groups led to the Allied Tribes of British Columbia in 1916. This was a group formed to oppose the McKenna-McBride Commission. They openly celebrated the potlatch again. But arrests happened, including of chiefs, starting in 1920. In 1923, two of their leaders, Peter Kelly and Andrew Paull, presented demands to the government. First, they asked for money (2.5 million CAD). Then, they asked for larger reservations (160 acres per family) and certain hunting and fishing rights. They also wanted education and health benefits. The government responded with the Great Settlement of 1927, which denied all land claims. Also, Native Americans were specifically forbidden from hiring lawyers to fight for their rights. This was because the highest court in London, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, recognized pre-European rights unless proven otherwise. The government delayed the issue from 1925, giving plenty of time before a parliamentary inquiry in 1927. At that time, Parliament passed the ban on hiring lawyers. Barely a year later, the Allied Tribes broke apart.

In 1931, the tribes formed the Native Brotherhood of British Columbia. This group published a monthly paper called Native Voice. They also joined the Indian Homemakers' Association and the Confederation of British Columbia Indians. In 1947, as part of a global movement for minority voting rights, Native Americans gained the right to vote at the provincial level. In 1951, they succeeded in getting cultural practices, like the potlatch, freed from all bans. Children were now allowed to attend public schools. People could get legal help. And the punishment for drinking or having alcohol was removed.

Since the Canadian government limited appeals to the Judicial Committee in London, after 1949, only Canadian courts could hear cases. However, in the early 1950s, Frank Calder of the Nisga'a started a new effort regarding land claims. Other groups, like the Nuu-chah-nulth, also began to organize (1958).

In 1960, Native Americans gained the right to vote at the federal level. But in 1965, the Court of Justice in Victoria tried to argue that the 1763 law had no power in undiscovered British Columbia. However, the Supreme Court rejected this. In 1969, the Chief Justice of British Columbia, Davey, still denied the Nisga'a land rights. But in 1973, the Supreme Court declared that the Nisga'a did hold these rights. While several provinces and the federal government now recognized land rights in principle, the province still refused. However, the ruling Social Credit Party then made a new argument: that nothing had been paid for giving up these rights when joining Canada.

In the mid-1980s, 75% of people in a Vancouver Sun poll recognized Native American rights. In 1988, the BC First Nations Congress was formed, led by Bill Wilson. Starting in 1989, he held informal talks with resource companies, which the government soon agreed to. Unrest in other provinces also led to blockades in British Columbia, especially among the St'at'imc. In 1992, the provincial government recognized both land rights and the right to self-government. In 1993, the provincial Supreme Court even recognized limited legal rights to non-reserve lands. Since then, treaty talks have been ongoing for each negotiating group. Of the Salish, only the Tsawwassen have accepted a treaty so far. Another has yet to be approved. But the Nisga'a treaty is the only one that has completed the entire process.

Economic Changes

The early fur trade put wealth, weapons, and political power into fewer hands. At first, tribes that benefited most from the fur trade had an advantage. But this also brought white people into their territory. The risk of getting sick from epidemics grew quickly.

The Coast Salish on the lower Fraser River (and Puget Sound) were affected first. Also, new farms made it impossible for Native American women to gather plants and dig for roots. Then, industrial fishing, supported by Canadian government rules against Native Americans, destroyed the Salish fish trade. Structures like the railroad bridge over the Fraser even blocked fish ladders, stopping some large fish runs. Dams also caused problems. Lakes, like Lake Sumas, were simply drained in the 1920s for farmland.

Native Americans increasingly worked as loggers, sawmill helpers, and for a time, even as miners in coal mines and as sailors. Others worked in the fishing industry. Men were mostly fishermen, and women cleaned and packed fish. But Chinese workers replaced them first in railroad construction. Then Japanese and Europeans took over in fishing. Laws prevented Native Americans from commercial fishing. They increasingly relied on day labor, unskilled work, and seasonal jobs.

New Industries and Salish Involvement

Until 1862, Native Americans were the main suppliers of building materials, labor, and food for the growing city of Victoria. In 1859, over 2,800 Native Americans camped near the city. This included about 600 Songhees, 405 Haida, 574 Tsimshian, plus 223 Stikine River Tlingit, 111 Duncan Cowichan, 126 Heiltsuk, 62 Pacheedaht, and 44 Kwakwaka'wakw. They had included the newcomers in their large trading system. They were so successful that even long wars were mostly avoided. The Makah in northwest Washington, who are part of the Nuu-chah-nulth, formed the Neah Bay Fur Sealing Company in 1880. They rented the ship Lottie in Port Townsend. Chief James Claplanhoo eventually bought the Lottie. Three more schooners were added, and finally the Discovery in Victoria. In 1886, Chief Peter Brown bought the schooner Champion.

When large coal deposits were found, it was thanks to the Nanaimo Coal Tyee. He asked the Hudson's Bay Company if a "black mountain burning" had any value. He himself had already shipped coal from there to Victoria. In 1852, Joseph MacKay, a senior officer at Fort Nanaimo, was happy with the work of the Native Americans in the mines. Half of the first 1400 barrels of coal dug up were from them. Many also joined unions. In 1890, Thomas Salmon, a Nanaimo resident, was sent to Ottawa to represent the Miners and Mine Labourers Protective Association. During the coal strike in Nanaimo from 1912 to 1914, Native Americans refused to work as strikebreakers. This led to them being put on blacklists.

But most Native Americans worked in the fishing industry. Around 1900, 1,500 to 2,000 worked as fishermen and rowers. By 1929, this number grew to 3,632. They also took part in the first fishermen's strike as early as 1893. They were involved in forming unions, like the Squamish in creating the International Longshoremen's Association in 1912. They also participated in the dock strikes in Vancouver in 1923 and 1935.

Since the 1960s, many jobs have been created in self-government thanks to government funding. These jobs were often held by women. Now, many tribes are trying to become economically independent again. They are using their land for tourism after many natural resources have been used up or destroyed. Since 1993, they have also been allowed to fish for salmon on the Fraser River for commercial purposes, but in a limited way. However, salmon numbers are greatly decreasing, partly due to fish farms and partly due to climate change.

Gambling, Entertainment, and Tourism (USA)

The Coast Salish in the United States took a different economic path. Here, the California Mission Indian Federation (1919-1965) first pushed for self-organization. This was followed in 1972 by the Southern California Tribal Chairmen's Association. In the Northwest, tribes joined together to form the Northwest Federation of Indians. Many of their leaders relied on existing treaties.

Seasonal jobs were available in the state's agriculture, especially during harvest season. For example, growing hops for beer provided many summer jobs. In many cases, families moved from one harvest job to the next.

In 1934, the U.S. stopped its policy of weakening tribal groups and breaking them into individuals. A big step forward was the 1987 court case, California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians. This case strengthened Native American self-rule. It stopped states from interfering with the important casino business. These gambling places have since become profitable entertainment centers. They have expanded beyond just gambling to offer full tourism and entertainment. Several Coast Salish tribes also have such casinos. These include the Muckleshoot, the Skokomish, the Tulalip, the Shoalwater Bay tribe, the Upper Skagit, and since 2009, the Snoqualmie.

At the same time, some tribes are growing rapidly. For example, the Puyallup on southern Puget Sound had only 50 survivors after severe epidemics by 1850. Their numbers grew slowly at first. Gaining land rights, self-rule, and economic independence not only brought new residents to the reservation. More and more people also recognized their Native American heritage. Today, the tribe has over 3,800 members again.

Spiritual Revival

The Indian Shaker Church mixes Christian and Native spiritual ideas. It started from the personal death and rebirth experiences of a Coast Salish man from Puget Sound named John Slocum. From there, the teachings, which began in 1882, spread to British Columbia.

The Winter Spirit Dance was rediscovered in the 1950s. It reached its peak in the 1990s. Even before the potlatch ban was lifted, there was a movement to revive it. When the ban was lifted in 1951, they could perform it publicly again. Ten years later, there were only about 100 dancers. But by the 1990s, 500 or more dancers often gathered. A song and spirit helper introduces the necessary knowledge. Rituals like bathing in the wilderness and limiting certain foods are meant to strengthen the new dancer in their separation from the everyday world.

Potlatches are now celebrated when someone receives an ancestor's name, for funerals, or to remember someone who has passed away. Guests from all over the Salish area are invited. Sometimes, everything in the house is given away.

The arts of carving, painting, and weaving have also been revived. Susan Point of the Musqueam has become famous nationally. Canoe building is also thriving. Canoe trips now attract many tourists. There are also competitions between tribes and clans.

Powwows, which are inter-tribal dance gatherings, have also become more popular. Still, not all songs can be sung and played. Some are tied to seasons or specific ceremonies, often to specific clans. These celebrations end each year with a large gathering of all Coast Salish people, crossing borders. The tribes take turns hosting.

Being involved in culture and history has made some people well-known. Sonny McHalsie, a Stó:lō, has researched and recorded many Halkomelem place names. His tribe employs him as a cultural specialist.

Education and Residential Schools

Before Europeans arrived, education included reciting oral traditions. This meant family histories, history, genealogies, legends, and myths. Elders were responsible for this. Young women were also taught by elders in special huts. For shamans, a mentor would teach them. Grandparents were very important in this. Even as children, the "historians" of families and tribes were chosen and taught.

The Residential Schools, which aimed to force Native children to adopt the "Canadian way of life," closed in the 1970s and 1980s. Both the churches and the government have since apologized for the conditions there. They have set up a program to make amends. Tribes, like the Stó:lō Band on Seabird Island, offer language courses and teach their children themselves. Language courses have increased sharply since the 1990s. More students are also going to high schools and universities. The First Nations House of Learning at the University of British Columbia has greatly helped with this.

Recent History

In 1977, the Gitksan-Carrier Declaration demanded, "Recognize our sovereignty, recognize our rights, so that we can fully recognize your rights." In 1982, section 35(1) of the Canadian Constitution recognized the claims of the original people (aboriginals). This put the relationship with the government on a new path. In the Delgamuukw Decision, the Supreme Court of Justice ruled that before 1867, aboriginal rights had never been taken away. So, they continued to exist since Canada was founded. Also, several court rulings said that Native Americans had the right to teach their culture to their children. Their territory was an important part of this. Therefore, any decision affecting this land would need to involve talking with the affected tribe. In 1997, the Supreme Court ruled that these rights include rights to land, resources, cultural traditions, and political independence.

This decision affects, for example, the fishing industry. It is Canada's fourth-largest industry. One-third of its value comes from British Columbia alone. It wasn't until the 1990 Sparrow decision that Native American fishing rights were recognized. These rights were given priority over other economic claims.

In 1993, British Columbia responded by creating the BC Treaty Commission. Its first goal was to clarify and resolve overlapping land claims. The process had six steps, aiming for a treaty at the end. But the treaty process has divided opinions. The number of groups who believe too many rights and titles are being given up is growing. Still, the first treaties are almost finished. The Sechelt, on the other hand, signed the Sechelt Indian Band Self-Government Act in 1986. Whether they are more than a local government remains to be seen.

Salish politics were often small-scale for a long time. This changed first with cross-border ties, and then with representatives in the highest government bodies. For example, Musqueam candidate Wendy Grant almost won the election for Grand Chief of the Assembly of First Nations.

One tribal council representing a larger group of Salish is the Hul'qumi'num Treaty Group, formed in 1993. It represents 6,200 members from the Chemainus First Nation, Cowichan Tribes, Halalt First Nation, Lake Cowichan First Nation, Lyackson First Nation, and the Penelakut Tribe. They are concerned about 59,000 hectares of land sold to settlers in the 1860s. And 268,000 hectares were given in 1884 to build the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway on Vancouver Island. Coal mining, logging, and other industries have left little of the original landscape. As a result, only 0.5% of the tribe's territory still has old-growth forest. Most reservations are smaller than 40 hectares. In the traditional tribal area, only 48,000 hectares are still Crown Land, which is 15%. Of this, 8,000 hectares are protected as parks. Over 84% is privately owned, with almost 200,000 hectares owned by a few timber companies. But poor communities fear that their members will slowly sell off their land if it becomes private.

In 1994, with changes in the law, there was a chance to find new ways to develop the capital of British Columbia, Victoria, under the Bamberton Town Development Project. The Environmental Assessment Office helped create a plan that considered the needs of six affected tribes: the Malahat, Tsartlip, Pauquachin, Tseycum and Tsawout Bands, and the Cowichan Tribes. The report described how these lands were traditionally and currently used. It also looked at their importance to the tribes. Lessons learned from this led to protecting various areas in the new city. It also resulted in Native American involvement in creating marine protected areas, like Race Rocks, in 1998. The Lester B. Pearson College teaching program now includes not only biology but also cultural aspects, in this case, of the Beecher Bay First Nations. The 13-Moon system is important again here. In 2000, the Beecher Bay invited everyone involved to a celebration. Following rituals, younger people served as helpers, honoring ancestors by burning food.

Among the Coast Salish, the number of women working as councillors has increased from 11% to almost 30% since the 1960s. The number of people employed by the Stó:lō nation grew tenfold between 1990 and 1997, from about 20 to 200. Now, people also get paid for important work they used to do for free, like caregiving, teaching, maintenance, and caring for the land.

The situation south of the U.S. border is greatly shaped by efforts to join the tourism and entertainment industries. Casinos and hotels have become major sources of income. At the same time, tribal territories are less clearly defined. They are also much more populated by people who are not tribal members. Additionally, tribes are often much larger. They mostly aim for self-governance and have their own political bodies, courts, and executive branches.

This history makes it hard to decide what makes a tribe, even though the government has seven criteria. Since only recognized tribes can run casinos, and casinos provide many jobs, some tribes try to stop unrecognized tribes from being accepted by the state. This helps them avoid competition. So, it's not just the government that delays and complicates these processes.

Despite these challenges, the Coast Salish see themselves as a united group across borders. Since 2007, they have been working on a plan to restore and protect the natural environment. Representatives from both Canadian and U.S. Salish tribes met on the Cowichan reservation in British Columbia and the Tulalip reservation in Washington in 2007 and 2008. These meetings have been held since 2005. Participants feel responsible for the entire coast claimed by Salish tribes. They call it the Salish Sea.

For the 2010 Winter Olympics planned on the land of the Squamish, St'at'imc, and other Salish tribes, some Squamish, especially the Native Youth Movement, oppose the use of land they claim ("No Olympics on Stolen Land"). However, the leaders of the four host tribes—the Lil'wat, Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh—support the Olympics and benefit from them.

Ten Salish tribes in the United States have applied for recognition but are not recognized (as of February 15, 2007). In Washington, these include the Steilacoom Tribe, the Snohomish Tribe of Indians (denied in 2004), the Samish Tribe of Indians, the Cowlitz Tribe of Indians, the Jamestown Clallam, the Snoqualmie Tribal Organization, the Duwamish Tribe (denied in 2002), the Chinook Indian Tribe/Chinook Nation (rejected 2003), and the Snoqualmoo Tribe of Whidbey Island. In Oregon, the Tchinouk Indians are not recognized (rejected 1986). The Mitchell Bay Band of San Juan Islands is also unrecognized.

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |