Salafi movement facts for kids

The Salafi movement or Salafism (Arabic: السلفية, romanized: al-Salafiyya) is a movement within Sunni Islam. It started in the late 1800s and has been important in the Islamic world ever since. The name "Salafiyya" means they want to go back to the ways of the "pious predecessors" (salaf). These were the first three generations of Muslims. They include Islamic prophet Muhammad and his companions (the Sahabah), then the Tabi'in, and finally the Tabi' al-Tabi'in. Salafis believe these early Muslims showed the purest form of Islam.

Salafis say they follow the Qur'an, the Sunnah (teachings of Muhammad), and the Ijma (agreement) of the early Muslims. They believe these sources are more important than later religious ideas. The Salafi movement wanted to renew Muslim life. It greatly influenced many Muslim thinkers and groups.

Salafi Muslims are against bid'a (new religious ideas that change Islam). They support following sharia (Islamic law). When it comes to politics, Salafis are often seen in three groups:

- Purists (or quietists): These are the largest group. They avoid politics.

- Activists: This group regularly gets involved in politics.

- Jihadists: This is a smaller group. They believe in armed struggle to bring back early Islamic ways.

In legal matters, Salafis often support ijtihad (thinking for yourself based on religious texts). They are against taqlid (blindly following the rules of old schools of law). Some Salafis still follow these schools, but they don't limit themselves to just one.

The start of Salafism is debated. Some historians say it began in the late 1800s. It was a movement against Westernization from European imperialism. Leaders like Al-Afghani, Muhammad Abduh, and Rashid Rida were part of this. However, Al-Afghani and Abduh didn't call themselves "Salafi." Today, this term is not used for them. Rashid Rida, a student of Abduh, followed a stricter Salafism. He was against Sufism and Shi'ism. He also supported the Wahhabi movement.

Today, Salafism usually refers to modern Sunni movements. These movements are inspired by older scholars like Ibn Taymiyya (who lived from 1263 to 1328 CE). These Salafis believe the 19th-century reformers were too focused on reason. They felt they didn't interpret religious texts in the most direct, traditional way.

Conservative Salafis see Syrian scholars like Rashid Rida (died 1935 CE) as important figures. They believe these scholars revived Salafi ideas in the Arab world. Rida's ideas were shaped by Syrian Hanbali and Salafi scholars who followed Ibn Taymiyya. Rida and his students made these ideas popular. They influenced many Salafi groups in the Arab world.

Some major Salafi movements today include:

- The Ahl-i Hadith movement in South Asia.

- The Wahhabi movement in Arabia.

- The Padri movement of Indonesia.

- Algerian Salafism led by Abdelhamid Ben Badis.

Contents

What "Salafi" Means

The word Salafi was used in older times to describe a group of theologians. These were the early Ahl al-Hadith movement. The writings of the medieval theologian Taqi al-Din Ibn Taymiyya (died 1328 CE) are very important to Salafis. They are often studied in Salafi schools.

Sometimes, people who criticize the movement call Salafis Wahhabi.

Only in modern times has "Salafi" been used for a specific movement and set of beliefs. Both modern and traditional Muslims might use the term. Both groups believe Islam has changed and needs to return to an earlier, purer form.

Main Beliefs

Many Sunni Muslims believe that the closer in time you are to Prophet Muhammad, the truer your Islam is. Salafis are religious and social reformers. They want to create certain ways of thinking and living, both for individuals and communities. Their main goal is to reform beliefs (theology). Important parts of their manhaj (Arabic: منهج, meaning method) include legal teachings and ways of living and doing politics.

The Salafi da'wa (invitation to Islam) is a method, not a madhhab (school of law) in fiqh (Islamic law). Salafis are against taqlid (blindly following) the four main law schools of Sunni fiqh. These are the Maliki, Shafi'i, Hanbali, and Hanafi schools. Salafis call themselves Ahlul Sunna wal Jama'ah and are also known as Ahl al-Hadith. The Salafiyya movement supports this early Sunni way of thinking.

Salafis focus a lot on doing things according to the known sunnah (Prophet Muhammad's way). This includes not just prayer, but daily activities. For example, many are careful to use three fingers when eating. They drink water in three sips, holding the cup with their right hand while sitting.

The main ideas of Ibn Taymiyya's school, sometimes called "Historical Salafism," are:

- Bringing back the true beliefs and practices of the Salaf al-Salih (pious early Muslims).

- Upholding tawhid (the oneness of God).

- Rejecting loyalty to specific madh'habs (schools of law).

- Following religious scriptures very literally.

- Being loyal to Islamic rulers who rule by Sharia (Islamic law).

- Being against bid'ah (religious innovations) and heresies.

Views on Taqlid (Following Old Rules)

Salafi thinking wants to change Fiqh (Islamic Law). They want to move away from Taqlid (following the legal rules of a specific Madhhab). Instead, they want to go directly back to the Prophet, his Companions, and the Salaf. This return to the Prophet's pure way is called "Ittiba" (following the Prophet by directly looking at the Scriptures).

In legal matters, Salafis are divided. Some reject strict taqlid (following old rules) in favor of ijtihad (independent thinking). Others remain faithful to the four main schools of law.

Even though Muhammad Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab (died 1792 CE) rejected Taqlid, Wahhabi scholars often followed the Hanbali madhhab. They generally allow Taqlid when following Fatwas (legal opinions). They also encourage following the madhhabs. While they said Taqlid was wrong and supported Ijtihad, historically, Wahhabi legal practice was mostly within the Hanbali school until recently.

Other Salafi movements believe taqlid is unlawful (forbidden). They challenge the authority of the legal schools. They think that since madhhabs appeared after the time of Salaf al-Salih (pious early Muslims), Muslims who follow a madhhab without checking the scriptures themselves might go astray.

These groups include scholars of the Ahl-i Hadith movement. They also include Muhammad Nasir Al-Din al-Albani (died 2000) and al-Shawkānī (died 1834). They completely condemn taqlid (imitation). They reject the authority of the legal schools. They say Muslims must seek religious rulings (fatwa) only from the Qur’an and Hadith. The Ahl-i Hadith scholars saw themselves as following no particular school.

Other Salafi scholars, like Sayyid Rashid Rida (died 1935), take a middle path. They allow ordinary people to do Taqlid only when necessary. But they say people must do Ittiba when they learn the scriptural evidence. Their legal method rejects loyalty to any specific law school. They look at books from all madhhabs. These scholars accept the rich history of Sunni Fiqh. They see the writings of the four Sunni law schools as helpful for making rulings today. Some Salafis even believe that following taqlid is a form of shirk (worshipping others besides God).

Today, Salafis generally do not follow the established rulings of any particular Madhhab. They say Taqlid (blind imitation) is a bid'ah (innovation). They are greatly influenced by the legal ideas of the Zahirite school. This school historically opposed the idea of fixed legal schools.

How Scholars are Organized

Bernard Haykel notes that Salafis have a less strict system for religious authorities (ulema). Most Salafis, unlike other traditional Muslims, don't follow a strict system that controls religious opinions. Salafi tradition is "relatively open, even democratic."

How They Understand Texts

Followers of the Athari school of theology often come from the Salafi movement. They follow the Athari works of Ibn Taymiyya. Ibn Taymiyya, though debated in his time, became a major scholar for Salafis. They call him Shaykh al-Islam. Other important figures include Ahmad ibn Hanbal.

While other groups respect early Muslims, they follow them through the lens of traditional law schools. Salafis try to follow the Salaf al-Salih (pious early Muslims) directly through recorded scriptures. They often skip the old law books.

Salafi Muslims believe the Qur'an and Sunnah (which they link to the Kutub al-Sittah, major hadith collections) are the only true sources for Islam. They believe new issues should be understood from the scriptures, considering modern times. But they are against using too much human reason to interpret scriptures. Salafi scholars also give less importance to medieval legal books. They prioritize texts from the early generations of the Salaf.

Salafis prefer practical action over arguments about meanings. Meanings are either clear or beyond human understanding. As followers of Athari theology, Salafis believe that using too much logic in theology (kalam) is forbidden. Atharis read the Qur'an and hadith (Prophet's traditions) very literally. Only their clear meanings have authority in beliefs. They do not try to understand the Qur'an with human reason. They believe the true meanings should be left to God alone (tafwid).

Ibn Taymiyya was known for criticizing groups like the Sufis, Jahmites, Asha'rites, and Shias. He wrote many books explaining his views.

Teachings of Ibn Taymiyya

Followers of the Salafiyya school see the medieval scholar Ibn Taymiyya as the most important classical authority in beliefs and spirituality. Ibn Taymiyya's writings form the main texts for Wahhabi, Ahl-i Hadith, and other Salafi movements.

According to Ibn Taymiyya, Tawhid (oneness of God) has three types:

- At-tawḥīd ar-rubūbiyya (Oneness in Lordship).

- At-tawḥīd al-ulūhiyya (Oneness in Worship).

- At-tawhid al-assmaa was-sifaat (Oneness in names and attributes).

Salafis adopt Ibn Taymiyya's interpretation of the Shahada (Islamic testimony). This means worshipping God alone "only by means of what He has legislated," without partners. This is the foundation of their faith. In modern times, Ibn Taymiyya's writings have inspired many Salafi movements. Salafis often call Ibn Taymiyya Shaykh al-Islām. Along with Ibn Taymiyya, his students like Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya, Ibn Kathir, and Al-Dhahabi are also highly referenced by Salafis.

Ibn Taymiyya's scholarly works strongly criticize other theological schools. He also said that it is allowed to call oneself a follower of the Salaf. He stated:

"There is no shame in declaring oneself to be a follower of the salaf, belonging to it and feeling proud of it; rather that must be accepted from him, according to scholarly consensus. The madhhab of the salaf cannot be anything but true. If a person adheres to it inwardly and outwardly, then he is like the believer who is following truth inwardly and outwardly."

History

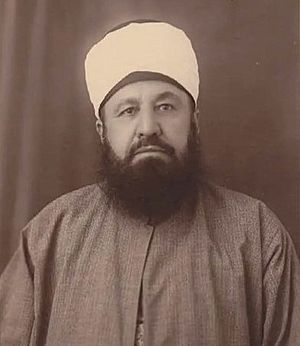

Historians say the Salafiyya movement started in the late 1800s in the Arab world. This was a time when European colonial powers were very strong. Key leaders included Jamal al-Din Qasimi (1866–1914) and Muhammad Rashid Rida (1865–1935). Before World War I, Salafi groups in the Arab East worked secretly. After the war, Salafi ideas spread among educated people. Political scholars like Rashid Rida also stressed the need for an Islamic state that follows Sharia (Islamic law). This laid the groundwork for a more conservative type of Salafiyya. It also influenced the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt.

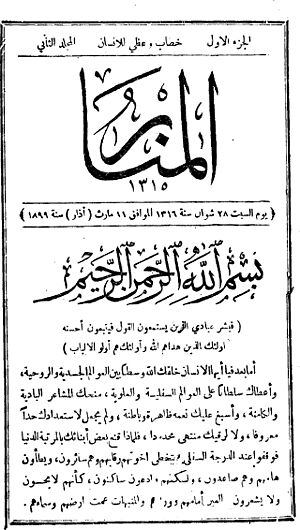

The term "Salafiyya" became popular through Syrian students of Tahir al-Jazairi. They were active in Egypt in the early 1900s. They opened the famous "al-Maktaba al-Salafiyya" ("The Salafi Bookshop") in Cairo in 1909. Rashid Rida worked with them from 1912. Together, they published old Islamic books, Hanbali writings, and pro-Wahhabi pamphlets. They also published many articles in their journal "Al-Majalla al-Salafiyya."

Salafis believe the term "Salafiyya" has existed since the first generations of Islam. They use quotes from medieval times to support this. For example, al-Sam'ani (died 1166) wrote about the surname "al-Salafi." He said it means someone who follows the pious ancestors and their beliefs. Athari theologian Al-Dhahabi described his teacher Ibn Taymiyya as someone who "supported the pure Sunna and al-Tariqa al-Salafiyah (Salafiyah way)." This referred to Ibn Taymiyya's way of understanding scriptures directly.

Origins

The Salafi movement looks up to the era of the Salaf al-Salih. These were the first three generations of Muslims after Prophet Muhammad. Salafis see their faith and practices as good examples. By trying to live like the Salaf, Salafis want to bring back a pure version of Islam. They want to remove all later additions, including the four schools of law and popular Sufism.

Salafism grew in different parts of the Islamic World in the late 1800s. It was a Muslim response to rising European imperialism. Salafi revivalists were inspired by the ideas of the medieval Syrian Hanbali theologian Ibn Taymiyya. He strongly criticized philosophy and parts of Sufism as wrong. Ibn Taymiyya's plan called for Muslims to return to the pure Islam of the Salaf al-Salih (pious ancestors). This meant understanding scriptures directly.

Other influences on the early Salafiyya movement included 18th-century Islamic reform movements. These were the Wahhabi movement in the Arabian Peninsula, movements in the subcontinent led by Shah Waliullah Dehlawi, and the Yemeni islah movement led by Al-Shawkani.

These movements believed that the Qur'an and Sunnah are the main sources of sharia. They felt that current laws should be checked against the Qur'an and Hadith. This idea was not new. It was a tradition kept alive within the Hanbali school of law. The Wahhabi movement, led by Muhammad Ibn Abd al-Wahhab, strongly brought back Hanbali traditionalism in 18th-century Arabia.

Evolution

In the mid-1800s in British India, the Ahl-i Hadith movement revived the teachings of Shah Waliullah and Al-Shawkani. They rejected Taqlid (following old rules) and focused on studying hadith. They took a very literal approach to hadith and rejected traditional legal structures. They leaned towards the Zahirite school.

In the 19th century, Hanbali traditionalism was revived in Iraq by the Alusi family. Three generations of Alusis helped spread the ideas of Ibn Taymiyya and the Wahhabi movement in the Arab world. All these reform ideas came together in the early Salafiyya movement. This movement was common across the Arab world in the late 1800s and early 1900s. It was closely linked to the works of Sayyid Rashid Rida (1865–1935).

Late 1800s

The first part of the Salafiyya movement appeared among reform-minded scholars (ulema) in the Arab parts of the Ottoman Empire in the late 1800s. The movement mainly used the works of Hanbali theologian Ahmad Ibn Taymiyya. His call to follow the path of Salaf inspired their name. This early group tried to find a middle way between religious knowledge ('ilm) and mysticism (Tasawwuf).

Damascus, a major center for Hanbali scholarship, was important in spreading these early Salafi ideas. Some scholars, like Amir 'Abd al-Qadir al-Jaza'iri, re-interpreted Ibn Arabi's mystical beliefs. They combined them with Ibn Taymiyya's opposing ideas to deal with new challenges. Other key figures included Jamal al-Din al-Qasimi and Tahir al-Jazairi. These reformers criticized parts of popular Sufism, but they didn't completely reject it.

The Cairene school of Muhammad Abduh started separately in the 1880s. It was influenced by the Damascene Salafiyya and Mu'tazilite philosophy. Abduh's movement sought a logical way to adapt to modernization. While Abduh criticized some Sufi practices, he still liked "true Sufism."

The Damascene Salafiyya was also influenced by reformers in Baghdad, especially the Alusi family. Abu Thana' Shihab al-Din al-Alusi (1802–1854) was the first of the Alusi scholars to promote reform ideas. He was influenced by Wahhabism. His son, Nu'man Khayr al-Din al-Alusi, was greatly influenced by Siddiq Hasan Khan, an early leader of the Ah-i Hadith movement. Khayr al-Din Alusi wrote many works supporting Ibn Taymiyya's teachings. The Iraqi reformers rejected Taqlid in law. They called for Ijtihad and condemned religious innovations like visiting tombs for worship.

Salafiyya ideas became strong in Syria by the 1880s. This was because they were popular among reformist scholars in Damascus. Many of Ibn Taymiyya's medieval writings were kept in Damascene mosques. Salafi scholars collected these works. The most influential Salafi scholars then were Tahir al-Jazai'ri, 'Abd al-Razzaq al-Bitar, and Jamal al-Din Qasimi. These scholars followed the 18th-century reformers who were influenced by Ibn Taymiyya. They called for a return to the pure early era of the Salaf al-Salih (righteous ancestors). Like Ibn Taymiyya in the 1200s, they saw themselves as preachers defending Tawhid (Islamic monotheism). They attacked bid'ah (religious innovations). They also criticized the Ottoman monarchy and its religious leaders, as well as Western ideas like nationalism.

After World War I

By the 1900s, reformers were known as "Salafis." This name also helped them show they were different from the Wahhabis of Najd. The Salafi turn against Ibn 'Arabi and Sufism happened later, after World War I. This was under the leadership of Rashid Rida. This second stage of Salafiyya was led by Rashid Rida and his students. They believed in understanding scriptures very literally. They were also very hostile to Western imperialism and culture. Rida's criticism of Sufism was very strong. He questioned the relationship between a student and a spiritual guide in mysticism. He also criticized the chains of teachers that Sufi groups used. Rida strongly criticized political quietism and peaceful ideas of some Sufi groups.

Rida's Salafiyya wanted a complete return to the religious and political ways of the salaf. Rashid Rida emphasized following the first four Rightly-Guided Caliphs (Khulafa Rashidin). Rida's efforts helped create a global Salafi community. Because of this, he is seen as one of the founders of the Salafiyya movement. His ideas inspired many Islamic revival movements.

Rashid Rida believed that reviving Ibn Taymiyya's ideas was the solution to the decline of the Islamic World. The Salafiyya movement became more conservative under Rida. It became very critical of the religious establishment. Rida's ideas deeply influenced Islamist thinkers of the Muslim Brotherhood. These included Hasan al-Banna (died 1949) and Sayyid Qutb (died 1966). They believed in a complete Islamic state and society, similar to the Wahhabi movement.

The early leaders of Salafiyya, like Sayyid Rashid Rida (died 1935), saw traditionalist theology as key to their social and political reform. Rashid Rida argued that Athari theology was true Sunni orthodoxy. He said it was less divisive and provided a stronger basis of faith than Ash'arism. According to Rida, Salafi beliefs were easier to understand than Kalam (speculative theology). This made them a stronger defense against atheism and other wrong beliefs.

Salafi reformers also praised the medieval theologian Ibn Taymiyya. They saw him as a perfect example of Sunni orthodoxy. They stressed that his strict idea of Tawhid was an important part of the forefathers' doctrine (madhhab al-salaf). Despite this, Salafi reformers at this time cared more about pan-Islamic unity. They avoided calling most other Muslims heretics. They presented their beliefs with moderation. Jamal al-Din Qasimi spoke against sectarianism and harsh arguments between Atharis and other theological schools.

From the mid-1920s, this leniency changed. Salafi activists and scholars became more partisan. Muhammad Bahjat al Bitar (1894–1976), a student of Rashid Rida, strongly criticized speculative theology. He wrote books that brought back Ibn Taymiyya's theological arguments. One such book, published in 1938, strongly criticized the Ottoman Maturidite scholar Muhammad Zahid al-Kawthari (1879–1952). Bitar accused him of heresy. In the book, Bitar strongly supported Ibn Taymiyya's literal approach to understanding God's attributes in the Qur'an.

Modern Times

The Syrian Salafiyya tradition had two main types: a non-political Quietist group and a "Salafi-Islamist hybrid." The early Salafiyya led by Rashid Rida focused on revolutionary Pan-Islamists. They had social and political goals. They wanted to bring back an Islamic Caliphate through military struggle against European colonial powers.

However, today's Salafiyya is mostly made up of Purists. These groups avoid politics and support Islamic Political Quietism. Modern Purist Salafism, known as "the Salafi Manhaj" (methodology), appeared in the 1960s. It combined three similar religious reform traditions: the Wahhabi movement in Arabia, the Ahl-i Hadith movement in India, and the Salafiyya movement in the Arab world from the late 1800s and early 1900s.

The person most responsible for this change was the Albanian Islamic hadith scholar Muhammad Nasir al-Din al-Albani. He was a student of Rashid Rida. He is seen as the "spiritual father" of the Purist Salafi group. All modern Salafis respect him as "the greatest hadith scholar of his generation."

As of 2017, journalist Graeme Wood estimated that Salafis make up "fewer than 10%" of Muslims worldwide. But by the 21st century, Salafi ideas had become so common that many modern Muslims, even if they don't call themselves Salafi, have adopted parts of Salafism.

In the modern era, some Salafis use the surname "Al-Salafi." They use the label "Salafiyya" to show a specific understanding of Islam. They believe it is different from other Sunnis in terms of 'Aqidah (creed) and how they approach Fiqh (legal tradition).

Salafi Political Groups

Some experts divide Salafis into three groups based on their political approach: purists, activists, and Jihadis. This idea was proposed by Quintan Wiktorowicz in 2006.

- Purists focus on teaching and spreading Islam. They want to make religious beliefs and practices pure. They avoid politics.

- Activists focus on political reform. They want to bring back a Caliphate through political actions, but not violence.

- Jihadists have similar political goals as activists, but they use armed struggle.

After the Arab Spring, Salafis in the Arab World formed political parties. These parties actively support Islamic social and political causes.

Purists

"Purists" are Salafists who focus on peaceful da'wah (preaching Islam), education, and "purifying religious beliefs and practices." They follow the Salafi aqida (creed). They see politics as "a distraction or even an innovation that takes people away from Islam." This group is also called conservative Salafism. Its followers try to stay out of politics. This method attracts many religious Muslims who want to focus only on religious goals, not political ones.

Conservative Salafis do not want to get involved in the problems that come with political activism. They believe that a long movement of "purification and education" for Muslims is needed for Islamic revival. This will create a "pure, uncontaminated Islamic society" and then establish an Islamic state.

Some purists never oppose rulers. Madkhalism, for example, is a type of Salafism that supports authoritarian regimes in the Middle East. This movement is named after the Saudi Arabian cleric Rabee al-Madkhali.

Salafi Activists

Further along the spectrum are the Salafi-Activists (or haraki). They believe in changing societies through political action. This group includes Islamist organizations like the Muslim Brotherhood, Egyptian Hizb al-Nour (Party of Light), and the Al Islah Party of Yemen. They are committed to finding "the Islamic solution" for all social and political problems. Salafi-Activists are strongly against secularism, Israel, and the West. Their plan is to work within the existing system to eventually replace it with an Islamic state.

Activists are different from Salafi-jihadists because they avoid violence. They also differ from Salafi purists because they get involved in modern political processes. Salafi-Activists have a long history of political involvement in major Arab Islamist movements like the Muslim Brotherhood. Salafi activism started in the 1950s and 60s in Saudi Arabia. Many Muslim Brothers found refuge there from persecution. They combined their Muslim Brotherhood beliefs with Salafism. This led to the Salafi activist trend, seen in the Sahwa movement in the 1980s.

Salafi parties are strong supporters of Sunni empowerment after the Arab Spring. They also warn against Iran's actions in the Arab World. Salafi activist scholars have criticized Iran's "Shia Crescent" project. They also criticize attempts to make people Shi'ite through population changes in countries like Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon.

Islamist movements like the Muslim Brotherhood and Jamaat-e-Islami are greatly influenced by Activist Salafi thought. This movement is very popular among followers of the Salafiyya school. It is often called "mainstream Salafism." Activist Salafis condemn violence. However, they actively participate in their societies' political processes to support shari'a. As of 2013, this group makes up the majority of Salafism.

This movement is strongly criticized by followers of the Madkhalist type of Quietist Salafism. Madkhalists completely withdraw from politics. Many Salafi activists criticize the policies of Gulf kingdoms. They have attacked Madkhalis for blindly following the political line of the Gulf monarchs. The Activist group, sometimes called "politicos," sees politics as "another area where the Salafi creed must be applied." This is to ensure justice and that "political rule is based on the Shari'a." Al–Sahwa Al-Islamiyya (Islamic Awakening), for example, has been involved in peaceful political reform. Safar Al-Hawali, Salman al-Ouda, Abu Qatada, and Zakir Naik are examples of this trend. They are active on social media and have gained support among young people.

It's very simple. We want sharia. Sharia in economy, in politics, in judiciary, in our borders and our foreign relations.

—Mohammed Abdel-Rahman, the son of Omar Abdel-Rahman, Time magazine. October 8, 2012

After the Arab Spring, Salafi Muslims became more active in politics. They supported various Islamic causes. Salafi activists strongly criticize the foreign policies of Western countries. They also criticize Iran's actions in the region, like its military involvement in Syria. Some Quietist Salafis have also started political parties. This is in response to threats from wars and outside interference in Arab countries. Examples include the Al-Nour Party in Egypt and Ansar al-Sunna in Sudan.

Salafi Jihadists

"Salafi Jihadism" is a term used to describe Salafi groups who became interested in armed jihad in the mid-1990s. These groups are often called "Salafi jihadis" or "Revolutionary Salafis." Journalist Bruce Livesey estimates that Salafi jihadists make up less than 1.0 percent of the world's 1.2 billion Muslims.

Another definition of Salafi jihadism is an "extreme form of Sunni Islamism that rejects democracy and Shia rule." This definition separates them from non-political Salafi scholars and from the sahwa movement. Dr. Joas Wagemakers defines Salafi-Jihadists as Salafis who support Jihad against secular rulers using armed, revolutionary methods. Sayyid Qutb, Abdullah Azzam, Usama Bin Laden, Ayman al-Zawahiri, and Abubakr al-Baghdadi are major figures in this movement. Jihadi Salafi groups include Al-Qaeda, ISIS, Boko Haram, and the Al-Shabaab.

All Salafi-Jihadists agree on overthrowing the current rulers through armed Jihad. They want to replace them with a Global Caliphate. They believe Jihad is essential to Islamic faith and is a personal duty (fard 'al-Ayn) for all Muslims. The Palestinian Jihadist scholar 'Abdallah ‘Azzam (1941–89) called it "the most excellent form of worship." Salafi-Jihadists see themselves as following Sayyid Qutb. He was an influential Islamist scholar who led the radical part of the Muslim Brotherhood in the 1960s.

Inspired by Ibn Taymiyya, they strongly support takfir (declaring someone an unbeliever) and the principles of Al-Wala' wa'l- Bara' (loyalty and disavowal). Like Qutb, they also made belief in Allah's exclusive rule (Hakimiyya) central to Tawhid. They condemn all other political ideas as Jahiliyya (ignorance). Sayyid Qutb's book Al-Ma‘alim Fi'l-tariq (The Milestones) outlined his plan to destroy Jahiliyya and replace it with Islam. This book became very influential among Salafi-Jihadi thinkers.

A study of the Caucasus Emirate, a Salafi jihadist group, in 2014 showed its strict following of tawhid and its rejection of shirk, taqlid, and bid‘ah. It believed that Jihad (holy war) is the only way to advance the cause of Allah on Earth. Purist and Activist Salafis often strongly disagree with the Jihadists and say their actions are not Islamic. Scholars point out that Salafi-Jihadi views are not typical of the wider Islamic tradition. Scholars and thinkers from across the Islamic world have strongly spoken against various Salafi-jihadi groups. They see them as "a perversion" of Islamic teachings.

Salafi Groups Around the World

Saudi Arabia

Modern Salafists consider the 18th-century scholar Muhammad bin 'Abd al-Wahhab and many of his students to be Salafis. He started a reform movement in the region of Najd. He invited people to Tawhid (monotheism). He also wanted to remove practices like visiting shrines and tombs, which were common among Muslims. Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab saw these practices as forms of idolatry and wrong innovations in Islam that went against Tawhid. He stressed the importance of obeying sharia. He also said Muslims should follow sharia by reading and following the Scriptures.

Like their important scholar Ibn Taymiyya, Wahhabis did not believe in blind-adherence (Taqlid). They supported using Ijtihad (legal reasoning) with the Qur'an and Hadith. They also emphasized simplicity in religious rituals. So, old legal works by Fuqaha were not seen as important as the Scriptures themselves. This is because the former were human interpretations, while the Qur'an is God's eternal word.

The Salafi movement in Saudi Arabia comes from Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab's reform movement. Unlike other reform movements, Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab and his students made a religious and political agreement with Muhammad Ibn Saud and his family. This allowed them to expand militarily and establish an Islamic state in the Arabian Peninsula. While most followers believed in Islamic revival through education, the militant parts of the movement used armed campaigns. They wanted to remove local practices seen as innovation and destroyed many shrines and tombs of saints (awliya).

Wahhabism is seen as a stricter, Saudi form of Salafism. Mark Durie says Saudi leaders use their money to fund and promote Salafism worldwide. Ahmad Moussalli agrees that Wahhabism is a part of Salafism. He says, "As a rule, all Wahhabis are salafists, but not all salafists are Wahhabis."

However, many scholars see a difference between the old Saudi Salafism (Wahhabism) and the new Salafism in Saudi Arabia. Stéphane Lacroix says that Salafism refers to all the mixtures that have happened since the 1960s between Muhammad bin ‘Abd al-Wahhab's teachings and other Islamic ideas. Hamid Algar and Khaled Abou El Fadl believe that in the 1960s and 70s, Wahhabism changed its name to Salafism because it couldn't spread as Wahhabism.

Saudi Arabia's money funded about "90% of the expenses of the entire faith" across the Muslim World. This included children's madrasas and high-level scholarship. "Books, scholarships, fellowships, mosques" were paid for. For example, "more than 1,500 mosques were built from Saudi public funds over the last 50 years." This spending has made the Saudi interpretation of Islam (sometimes called "petro-Islam") seem like the correct one to many Muslims.

Salafis are sometimes called "Wahhabis," often in a negative way by their opponents. Some Western critics often mix up Wahhabis and Salafis. However, many Western academics have challenged this. While Wahhabism is a Salafist movement in Arabian Peninsula inspired by Muhammad ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab, the broader Salafist movement has deeper roots across the Muslim World. Often, other Salafis disagree with Gulf-based Wahhabis on various issues and engage in different political activities.

Indian Subcontinent

In the Indian subcontinent, there are several Salafi groups, including Ahl-i Hadith and Kerala Nadvathul Mujahideen. Ahl-i Hadith is a religious movement that started in Northern India in the mid-1800s. Its followers believe the Quran, sunnah, and hadith are the only sources of religious authority. They oppose anything introduced into Islam after the earliest times. They reject taqlid (following old rules) and favor ijtihad (independent legal reasoning) based on the scriptures. The movement's followers call themselves Salafi. Others call them Wahhabi or see them as a type of Wahhabi movement. In recent decades, the movement has grown in Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan.

Shah Waliullah Dehlawi (1703-1762) is seen as the intellectual founder of the movement. His rejection of Taqlid was emphasized by his son Shah Abdul Aziz and later by Shah Ismail in a purer way. This led to the Jihad movement of Sayyid Ahmad Barelvi (1786-1831). This movement expanded Shah Waliullah's rejection of Taqlid as a core belief. They focused on waging physical Jihad against non-Muslims and removing mixed rituals common among Muslims.

Although the Indian Mujahidin movement shared similarities with the Arabian Wahhabi movement, they mostly developed separately. After Sayyid Ahmad's death in 1831, his followers continued Jihad activities throughout British India. They played an important role in the Rebellion of 1857. After the revolt was defeated, the British crushed the Mujahidin. By 1883, the movement was fully suppressed. Many followers abandoned physical Jihad and chose political quietism. The Ahl-i-Hadith movement came from these religious activists.

In 19th century British India, the Ahl-i Hadith movement grew as a direct and quietist result of the Indian Mujahidin. The early leaders were influential hadith scholars Sayyid Nazir Hussein Dehlawi (1805-1902) and Siddiq Hasan Khan of Bhopal (1832-1890). They were directly taught by the lineage of Shah Waliullah and the Indian Mujahidin movement. The Ahl-i Hadith movement drew directly from the teachings of Shah Waliullah and Al-Shawkani. They advocated rejecting Taqlid and reviving hadith. However, they differed from Shah Waliullah's softer approach to old legal theory. They aligned themselves with the Zahirite (literalist) school and took a literal hadith approach. They also rejected the authority of the four legal schools. Their goal was to live a pious and ethical life according to the Prophetic example in every part of life.

Kerala Nadvathul Mujahideen (KNM) was founded in 1950 in Kerala. It is a popular reform movement. KNM has had several splits since 2002. All existing groups maintain good connections with Arab Salafi groups, especially in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait.

Folk Islam and Sufism, which are popular among the poor, are strongly opposed by Ahl-i Hadith. This attitude towards Sufism has caused conflict with the rival Barelvi movement. Ahl-i Hadith followers identify with the Zahiri madhhab. The movement gets inspiration and money from Saudi Arabia. Jamia Salafia is their largest institution in India.

Egypt

The Egyptian Salafi movement is one of the most influential branches of the Salafi movement. It greatly impacted religious groups across the Arab world, including scholars in Saudi Arabia. Salafis in Egypt are not united under one group. The main Salafi groups in Egypt are Al-Sunna Al-Muhammadeyya Society, The Salafist Calling, al-Madkhaliyya Salafism, Activist Salafism, and al-Gam’eyya Al-Shar’eyya. Salafi-Wahhabi ideas were brought to Egypt by the Syrian scholar Rashid Rida starting in the 1920s. Rashid Rida opposed the Westernizing cultural trends adopted by Egyptian liberal elite. He said nationalist ideas were a plot to weaken Islamic unity. Rida and his students campaigned for an Islamic state based on Salafi principles. They became the biggest opponents of Egyptian secularists and nationalists.

Al-Sunna Al-Muhammadeyya Society

Al-Sunna Al-Muhammadeyya Society, also known as Ansar Al-Sunna, was founded in 1926 by Sheikh Mohamed Hamed El-Fiqi. He graduated from Al-Azhar in 1916 and was a student of the famous Muslim reformer Muhammed Abduh. It is considered the main Salafi group in Egypt. El-Fiqi's ideas were against Sufism. But unlike Muhammed Abduh, Ansar Al-Sunna follows the Tawhid as taught by Ibn Taymiyya. Many Saudi scholars became students of important scholars of Ansar al Sunna.

Most Egyptian Salafis are part of Ansar al-Sunna al-Muhammadiyya. This movement was started by Muhammad Hamid al-Fiqqi (a student of Salafi scholar Rashid Rida). It aims to defend traditional Salafism. The movement has a good relationship with Arabian Wahhabi scholars. It greatly benefited from the rise of Salafism since the 1970s. The movement traces its first Wahhabi contacts to Rashid Rida. Al-Azhar has a close relationship with Ansar al-Sunna. Most early leaders of Ansar al-Sunna were Azhari graduates. Many of its current scholars studied at Al-Azhar.

Salafist Call (al-daʿwa al-salafiyya)

Salafist Call (al-daʿwa al-salafiyya) is another influential Salafist organization. It came from student activism in the 1970s. While many activists joined the Muslim Brotherhood, a group led by Mohammad Ismail al-Muqaddim started the Salafist Calling between 1972 and 1977. This group was influenced by Salafists from Saudi Arabia. Salafist Call is the most popular Salafi group in Egypt. Because it is a local mass movement with strong political views, it does not have a good relationship with Saudi Arabia.

Da'wa Salafiyya emphasizes its Egyptian history more than Ansar al-Sunna. It traces its history through the persecution of Ibn Taymiyya in Egypt. It then links to the challenges faced by the Muwahhidun movement in Arabia. Finally, it connects to scholars like Sayyid Rashid Rida who made Ibn Taymiyya's ideas popular in early 20th-century Egypt. Unlike Ansar al-Sunna, which preaches political quietism, Salafist Call is a politically active movement.

The Al-Nour Party

The Al-Nour Party was created by Salafist Call after the 2011 Egyptian Revolution. It has a very conservative Islamist ideology. It believes in strictly applying Sharia law. In the 2011–12 Egypt parliamentary elections, the Islamist Bloc led by Al‑Nour party received 28% of the votes. The Islamist Bloc gained 127 of the 498 parliamentary seats. Al‑Nour Party itself won 111 of these seats.

From January 2013, the party slowly moved away from Mohamed Morsi's Muslim Brotherhood government. It was involved in the large protests in late June against Morsi's rule. This led to a military coup that removed him from office in July that year.

According to Ammar Ali Hassan, Salafis and the Muslim Brotherhood agree on many things. For example, they both want to make society more "Islamic" and require all Muslims to give alms. However, Salafis have rejected the Muslim Brotherhood's flexibility on whether women and Christians should hold high office. They also disagree with the Brotherhood's relatively tolerant attitude towards Iran.

Malaysia

In 1980, Prince Mohammed bin Faisal Al Saud of Saudi Arabia offered Malaysia $100 million for a finance company. Two years later, the Saudis helped fund the government-sponsored Bank Islam Malaysia. In 2017, it was reported that Salafi ideas are spreading among Malaysia's leaders. The traditional Islamic theology taught in government schools is shifting towards a Salafi view from the Middle East, especially Saudi Arabia. The Saudi-backed Salafist wave in Malaysia has led to more anti-Shi’a Muslim talk and the increasing Arabization of Malay culture.

Yemen

Islamic scholar Muhammad Ibn 'Ali ash-Shawkani (1759 - 1839 CE) is seen as an intellectual ancestor by Salafis in Yemen. They use his works to promote Salafi revivalist ideas. His works are widely used in Salafi schools beyond Yemen. He also greatly influenced other Salafi movements worldwide, like the Ahl-i Hadith in the Indian subcontinent.

Tunisia

Salafism has been called "ultra-conservative" in Tunisia after the 2011 revolution.

Turkey

Turkey has not been much discussed in studies of global Salafism. Salafism is a small part of Turkish Islam. It grew as the state tried to use religion to support Turkish nationalism in the 1980s. Even though Salafism became a topic in Turkish media and studies, a lack of clear spelling for the term shows that its importance in Turkey is often denied. It also shows how successful republican secularism has been in removing religion from public discussion.

However, since the 1980s, Salafi preachers trained in Saudi Arabia have found a place through publishing houses. These houses have translated Arabic texts from the Saudi Salafi scene. They aim to change the way Turkish Islam is discussed. In 1999, the Turkish Directorate of Religious Affairs Diyanet recognized Salafism as a Sunni school of thought. Salafist preachers then started to gain influence in Turkish society.

With Turkish citizens and the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government involved in the Syrian civil war, public discussion began to question if Salafism was truly foreign to Turkey. Salafism became a visible part of religious discussion in Turkey. This happened as the military regime tried to outmaneuver movements challenging the Kemalist secular order.

The military authorities increased the budget of the religious affairs administration (known as Diyanet) by over 50%. It grew from 50,000 employees in 1979 to 85,000 in 1989. Turkey also sought closer ties with Saudi Arabia. It became more involved in pan-Islamic institutions under Saudi guidance. Diyanet received Muslim World League funding to send officials to Europe. This was to develop outreach activities in Turkish immigrant communities. A network of business and cultural links was formed with Saudi businesses and institutions.

Preachers who studied at the Islamic University of Madinah and identified as Salafi also set up publishing houses and charity groups. The most prominent example is Iraqi-Turkish Salafi scholar and preacher Abdullah Yolcu. He preaches under the Guraba publishing house. They faced harassment and arrest by security forces. But they became more public after the AKP gained power in 2002. Turkish Salafis became active on YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook. They also had websites for their publishing businesses.

Saudi-based scholars like Bin Baz, al-Albani, Saleh Al-Fawzan (born 1933), and Muhammad ibn al-Uthaymeen (1925-2001) are their main references. They avoid contemporary scholars linked to the Muslim Brotherhood, like Yusuf al-Qaradawi (born 1926). Turkish is their main language, but Arabic is important in special website sections. Arabic Salafi texts are in their bookstores. They also use many Arabic terms in their Turkish texts. Abdullah Yolcu is the most established among them. He is known for "producing Turkish Salafism from Arabic texts."

China

Salafism is opposed by many Hui Muslim Sects in China. These include the Gedimu, Sufi Khafiya, and Jahriyya. Even the fundamentalist Yihewani (Ikhwan) Chinese sect, founded by Ma Wanfu after Salafi inspiration, called Ma Debao and Ma Zhengqing heretics. This was when they tried to make Salafism the main form of Islam. Ma Debao started a Salafi school, called the Sailaifengye (Salafi), in Lanzhou and Linxia. It is completely separate from other Muslim sects in China. Hui Muslims avoid Salafis, even if they are family members.

The Kuomintang Sufi Muslim General Ma Bufang, who supported the Yihewani (Ikhwan) Muslims, persecuted the Salafis. He forced them into hiding. They were not allowed to move or worship openly. The Yihewani had become secular and Chinese nationalists. They saw the Salafiyya as "heterodox" (xie jiao) and people who followed foreign teachings (waidao). After the Communists took power, Salafis were allowed to worship openly again.

Vietnam

An attempt to spread Salafism among the Muslim Chams in Vietnam has been stopped by the Vietnamese government. However, the loss of Salafis among Chams has benefited Tablighi Jamaat.

Qatar

Similar to Saudi Arabia, most citizens of Qatar follow a strict type of Salafism called Wahhabism. Qatar's national mosque is the Imam Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab Mosque, named after the founder of Wahhabism. Like Saudi Arabia, Qatar has also funded the building of mosques that promote Wahhabi Salafism.

However, Qatar shows a different view of Wahhabism compared to Saudi Arabia. In Qatar, women are allowed to drive. Non-Muslims can buy pork and liquor from a state-owned center. Religious police do not force businesses to close during prayer times. Qatar also hosts branches of several American universities and a "Church City" where migrant workers can practice their religion. This more open interpretation of Wahhabism is largely credited to Qatar's young Emir, Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani.

Yet, Qatar's more tolerant Wahhabism has drawn criticism from Qatari citizens and foreigners. The Economist reported that a Qatari cleric criticized the state's acceptance of non-Islamic practices away from public view. He complained that Qatari citizens are oppressed. Although gender separation in Qatar is less strict than in Saudi Arabia, plans for co-ed lectures were stopped after threats to boycott Qatar's segregated public university. There have also been reports of local unhappiness with alcohol sales in Qatar.

Qatar has also been criticized for trying to spread its religious ideas through military and non-military ways. Militarily, Qatar has been criticized for funding rebel Islamist extremist fighters in the Libyan Crisis and the Syrian Civil War. In Libya, Qatar funded allies of Ansar al-Sharia. This jihadist group is thought to be behind the killing of former U.S. ambassador Christopher Stevens. Qatar also sent weapons and money to the Islamist Ahrar al-Sham group in Syria. Also, Qatar-based charities and online campaigns, like Eid Charity, have financed terrorist groups in Syria. Qatar has also given financial support to the Gaza government led by the militant Hamas organization. Senior Hamas officials have visited Doha and hosted Qatari leaders in Gaza. Qatar also gave about $10 billion to Egypt's government when Mohamed Morsi was in office.

Non-militarily, Qatar's state-funded broadcaster Al Jazeera has been criticized for biased reporting that matches Qatar's foreign policy goals. Also, reports have condemned Qatar's funding of mosques and Islamic centers in Europe. These are seen as attempts to spread the state's Salafist interpretation of Islam. Reports of Qatar trying to influence the curriculum of U.S. schools and buy influence in universities have also spread.

The nearby Persian Gulf States of Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates have criticized Qatar's actions. In 2014, these three countries withdrew their ambassadors from Qatar. They said Qatar failed to commit to not interfering in the affairs of other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. Saudi Arabia also threatened to block land and sea borders with Qatar. This blockade ended on January 5, 2021, when Saudi and Qatar authorities reached common ground, with Kuwait's help.

How Many Salafis Are There?

It is often reported that Salafism is the fastest-growing Islamic movement in the world. This comes from various sources, including the German domestic intelligence service (Bundesnachrichtendienst). The Salafiyya movement has also become accepted as a "respected Sunni tradition" in Turkey since the 1980s. This happened when the Turkish government became closer to Saudi Arabia. This led to cooperation between the Salafi Muslim World League and the Turkish Diyanet. Diyanet recognized Salafism as a traditional Sunni theological school, bringing Salafi teachings to Turkish society. Globally, Salafism in Islamic religious discussions grew at the same time as pan-Islamist Movements. Both emphasized the concept of Tawhid.

Important Salafis

- Abdur-Rahman al-Mu'allimee al-Yamani, Yemeni Scholar and the Librarian of the Grand Mosque's Library in Mecca (died 1966)

- Abd al-Aziz Ibn Baz, Saudi Grand Mufti (died 1999)

- 'Abd al-Hamid ibn Baadis, an Algerian scholar (died 1940)

- 'Abd al-Rahim Green

- Abdullah al-Ghudayyan, Saudi Arabian Salafi scholar (died 2010)

- Abu Qatada, Palestinian-Jordanian cleric

- Ali al-Tamimi, contemporary American Islamic leader

- Bilal Philips, Canadian Salafi imam

- Ehsan Elahi Zaheer, Pakistani scholar (died 1987)

- Feiz Mohammad

- Haitham al-Haddad, British Salafi cleric

- Ibn Taymiyyah, influential early Islamic scholar.

- Muhammad al-Amin al-Shanqiti, a Mauritanian scholar (died 1974)

- Muhammad Asadullah Al-Ghalib, a Bangladeshi reformist Islamic scholar and leader of the Salafi organisation Ahlehadith Movement Bangladesh

- Muhammad ibn Salih al-Munajjid, founder of IslamQA website

- Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, religious leader and scholar.

- Muhammad ibn Ali al-Shawkani prominent Yemeni Islamic theologian, hadith scholar and jurist

- Muhammad ibn al-Uthaymeen, Saudi Arabian scholar (died 1999)

- Muhammad Nasir al-Din Al-Albani, Syrian-Albanian hadith scholar and theologian (died 1999)

- Muhammad Rashid Rida, a Syrian-Egyptian scholar (died 1935)

- Rabee al-Madkhali, leader of the Madkhalist movement

- Saleh Al-Fawzan, a Saudi Arabian Islamic scholar

- Umar Sulaiman Ashqar, author of the Islamic Creed-series

- Zakir Naik, Salafi ideologue in India

- Zubair Alizai (1957–2013); Pakistani hadith scholar and Hafiz

- Othman al-Khamees, Salafi ideologue in Kuwait

- Abdur Razzaque Bin Yusuf, a Bangladeshi reformist Islamic scholar, Ahle Hadith leader and Founder of Al Jamiah As Salafiah

See also

In Spanish: Salafismo para niños

In Spanish: Salafismo para niños

- Deobandi movement

- International propagation of Salafism and Wahhabism

- Islam in Saudi Arabia

- Islamic fundamentalism

- Islamic schools and branches

- Glossary of Islam#Manhaj

- Sufi–Salafi relations

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |