African baobab facts for kids

Quick facts for kids African baobab |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Mature, flowering tree in Tanzania | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Malvales |

| Family: | Malvaceae |

| Genus: | Adansonia |

| Species: |

A. digitata

|

| Binomial name | |

| Adansonia digitata |

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The African baobab (scientific name: Adansonia digitata) is the most common type of baobab tree. It grows naturally in Africa and parts of the Arabian Peninsula. These amazing trees live for a very long time. Some have been found to be over 2,000 years old!

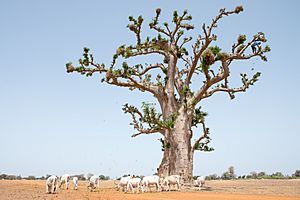

You'll usually find baobabs in hot, dry grasslands called savannas in sub-Saharan Africa. They are huge and stand out, often showing where water might be nearby. People have always valued them for food, water, medicine, and shelter. Many animals also rely on them for food. Baobabs are part of many old stories and beliefs. Sadly, many of the oldest and largest baobabs have died recently, possibly because of climate change. People also call the baobab the monkey-bread tree, upside-down tree, or cream of tartar tree.

Contents

About the Baobab Tree

African baobabs often grow alone, making them a unique part of the savanna landscape. They can grow from 5 to 25 meters (about 16 to 82 feet) tall. Their trunks are usually very wide and can be fluted or round. Some trunks can be 10 to 14 meters (about 33 to 46 feet) across!

Many large, old baobabs have a hollow center. This can happen when the oldest wood decays. But in baobabs, it's often because several stems grow together in a circle from the roots, forming a single, hollow trunk. The bark is gray and smooth. The main branches can be enormous.

Baobabs are deciduous trees, meaning they lose their leaves during the dry season. They can stay leafless for about eight months of the year. Their flowers are large, white, and hang down. The fruits are round with a thick shell.

Leaves, Flowers, and Fruit

The leaves of a mature baobab look like a hand with 5 to 7 (sometimes up to 9) leaflets. Younger trees might have simpler leaves.

Baobabs flower in both the dry and wet seasons. The flowers are beautiful and usually hang alone on a long stalk. The petals are white and can be up to 8 cm (about 3 inches) long. The flowers open in the late afternoon and stay open for only one night. When fresh, they smell sweet, but after about 24 hours, they turn brown and start to smell like rotting meat. This smell helps attract bats and other animals that pollinate them. Each flower has many stamens, sometimes up to 2,000!

All baobab trees produce large, round fruits that can be up to 25 cm (about 10 inches) long. African baobab fruits vary in shape, from almost round to cylindrical. The shell is thick, about 6 to 10 mm (about 0.2 to 0.4 inches). Inside, there's a soft, light beige pulp. As it dries, this pulp becomes a crumbly powder. The seeds are hard and kidney-shaped. They only sprout after a fire or after an animal eats them and passes them through its digestive system. This is because their hard seed coat needs to be cracked or thinned for water to get in.

-

Hanging fruits at Ala Moana Beach Park, Oahu in Hawaii

How Baobabs Store Water

Baobab trees are amazing at storing water in their trunks and branches. This helps them survive in dry areas where water is scarce. Their spongy bark helps them soak up water deep into their tissues. The U-shaped branches also guide rainwater down the trunk for maximum absorption.

The water is stored in special cells called parenchyma cells. A very large baobab can hold as much as 136,400 liters (about 36,000 gallons) of water!

During the dry season, baobabs drop all their leaves. This stops them from losing water through their stomata (tiny pores on leaves). If they kept their leaves, too much water would evaporate, and the tree would dry out. The trunk's size can shrink by a few centimeters during this time as it uses its stored water.

The water stored in the trunk is mostly for long-term survival during severe droughts. It's not easily used for daily needs. Baobabs have a lot more water and parenchyma cells than most trees. This helps them grow very large without needing a lot of energy.

How Long Do Baobabs Live?

The growth rate of baobab trees depends on how much groundwater or rain they get. They have faint growth rings, but counting them isn't a good way to tell their age. This is because a tree might form many rings in one year or none at all in another.

Scientists use Radiocarbon dating to find out the true age of baobabs. The Panke baobab in Zimbabwe was about 2,450 years old when it died in 2011. This made it the oldest flowering plant ever recorded! Two other trees, Dorslandboom in Namibia and Glencoe in South Africa, were around 2,000 years old. Baobabs can live so long partly because they can grow new stems over time.

Baobab Family Tree

The scientific name Adansonia honors the French explorer and botanist, Michel Adanson (1727–1806). He wrote the first detailed description of the baobab tree. The word "digitata" refers to the "digits" or fingers of a hand. This is because the baobab's leaves have leaflets that spread out like fingers.

A. digitata is the main species in the Adansonia group. Most other Adansonia species have two sets of chromosomes (diploid), but the African baobab has four sets (tetraploid). Some scientists think that the African baobab might actually be more than one species because its fruits vary a lot in shape from place to place. For example, in Angola, the fruits are long instead of round.

Baobab History

The first written records of the African baobab come from a 14th-century travel diary by an Arab traveler named Ibn Batuta. The first botanical description was in 1592, looking at fruits from Egypt. They were called "Bahobab," possibly from the Arabic "bu hibab," meaning "many-seeded fruit."

Michel Adanson saw a baobab tree in Senegal in 1749 and wrote the first detailed description of the whole tree. He named the group "Baobab." Later, Linnaeus renamed the group Adansonia to honor Adanson. But "baobab" stuck as a common name. Other common names include "monkey-bread tree" (because its soft, dry fruit is edible), "upside-down tree" (because its sparse branches look like roots), and "cream of tartar tree" (because of its powdery fruit pulp).

Where Baobabs Grow

The African Baobab is linked to tropical savannas. It likes dry climates and doesn't do well in very wet or frosty areas, or in deep sand. It grows naturally across mainland Africa, from about 16° North to 26° South. Some people think it was introduced to Yemen and Oman, while others believe it's native there. The tree has also been brought to many other places, including Australia and Asia.

Its northern limit in Africa is based on rainfall. It only grows naturally into the Sahel along the Atlantic coast and in the Sudanian savanna. It's not very common in Central Africa and only grows in the very north of South Africa. In East Africa, baobabs also grow in shrublands and along the coast. In Angola and Namibia, they grow in woodlands and coastal areas, as well as savannas.

Baobabs are native to many African countries, including Mauritania, Senegal, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Mali, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Niger, Nigeria, northern Cameroon, Chad, Sudan, Congo Republic, DR Congo, Eritrea, Ethiopia, southern Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Mozambique, Angola, São Tomé, Príncipe, Annobon, South Africa (in Limpopo province), Namibia, and Botswana. They have been introduced to places like Java, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Philippines, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Haiti, Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Seychelles, Comoros, India, and parts of China. Arab traders brought them to northwestern Madagascar, where they were often planted in the center of villages.

Baobab Ecology

African baobabs are found mostly in savanna habitats, which often have fires. They have special ways to survive fires, like thick, fire-resistant bark and thick-shelled fruit. Trees older than about 15 years have bark thick enough to handle most savanna fires. Younger trees can grow back after a fire. The thick shell of the fruit probably protects the seeds.

Fruit bats are the main pollinators of African baobabs, especially in West Africa. Other animals like bush babies and insects also visit the flowers.

Baobab seeds have a hard coat, so they can stay dry and alive for a long time. Animals like elephants and baboons eat the fruits, and when the seeds pass through their digestive system, they are more likely to sprout. This helps spread the seeds far away. The fruits also float and the seeds are waterproof, so water can help spread them too. Scientists think that baobabs might need pollen from another tree to produce fertile seeds. Trees growing alone might produce fruit, but the seeds inside might not be able to grow.

The fruit, bark, roots, and leaves of baobabs are important food sources for many animals. The trees themselves also provide important shade and shelter.

Protecting Baobabs

The baobab is a protected tree in South Africa. However, it is still threatened by mining and development. In the Sahel region, droughts, desertification (when land becomes like a desert), and too much harvesting of the fruit are causing problems. As of March 2022, the African baobab is not yet listed as endangered by the IUCN Red List, but there is evidence that their numbers might be going down. Many of the largest and oldest African baobabs have died in recent years. Scientists believe that Greenhouse gases, climate change, and global warming are making baobabs live shorter lives.

How People Use Baobabs

People have always valued baobab trees as sources of food, water, medicine, and shelter. The baobab is a traditional food plant in Africa, but it's not well-known elsewhere. Michel Adanson, the botanist, thought the baobab was "probably the most useful tree in all." He drank baobab juice twice a day in Africa and believed it kept him healthy. Some modern guides say the juice can help with diarrhea.

The roots and fruits are edible. The fruit is thought to help improve nutrition, make food supplies more secure, help rural areas develop, and support sustainable land care. In Sudan, where the tree is called tebeldi, people make tabaldi juice by soaking the dry fruit pulp in water. Water can also be taken from some of the tree trunks.

Baobab leaves can be cooked and eaten like a vegetable. Young, fresh leaves are used in sauces, and sometimes they are dried and powdered. This powder is called lalo in Mali and is sold in many village markets in West Africa. The leaves are used in a soup called miyan kuka in Northern Nigeria and are full of good nutrients and minerals. The seeds can be ground into flour or pressed to get oil for cooking.

Baobab leaves are sometimes used to feed animals like cows and goats during the dry season. The leftover material after oil is extracted from the seeds can also be used as animal feed.

The strong fibers from the bark can be used to make cloth. In times of drought, elephants will even eat the juicy wood under the baobab's bark.

Baobab for Export

In 2008, the European Union approved the use of baobab fruit for food. It is now often used in smoothies and cereal bars. In 2009, the United States Food and Drug Administration said that dried baobab fruit pulp was safe to use as a food ingredient.

Baobabs in Culture

Along the Zambezi, some tribes believed that baobabs were too proud. The gods got angry, pulled them out of the ground, and threw them back in upside-down. They say evil spirits cause bad luck to anyone who picks the sweet white flowers, and a lion will kill them.

In Kafue National Park, one of the biggest baobabs is called "Kondanamwali," or the "tree that eats maidens." The story says the tree fell in love with four beautiful maidens. When they grew up and found husbands, the tree got jealous. So, one stormy night, the tree opened its trunk and pulled the maidens inside. A rest house has been built in the branches of this tree. On stormy nights, people say you can still hear the crying of the trapped maidens. Some people believe that women living near many baobabs will have more children. This might be true because they would have better access to the tree's vitamin-rich leaves and fruits, which helps their diet.

The baobab tree also appears in Antoine De Saint-Exupéry’s famous children’s book, The Little Prince. In the story, baobabs are shown as dangerous plants that must be removed from a small planet. If not, they could grow too big and even break the planet apart.

Famous Baobab Trees

Many individual baobab trees are famous because of their age, size, history, or location.

Botswana

Around Gweta, Botswana, some baobabs are national monuments. Green's Baobab, south of Gweta, has carvings from 19th-century hunters and traders, including "Green’s Expedition 1858–1859." An older carving says "1771."

About 11 km (about 7 miles) south of Green's Baobab is Chapman's Baobab, also called Seven Sisters. It was once a huge tree with many stems. Explorers and traders used it as a landmark, and a hollow in its trunk served as a mailbox. Famous explorers like David Livingstone camped here. The tree had a circumference of 25 meters (about 82 feet) before its parts collapsed in 2016. However, some parts are still alive.

Seven trees known as the Sleeping Sisters or Baines' Baobabs grow on a small island in Kudiakam Pan, Botswana. They are named after Thomas Baines, who painted them in 1862. The giant tree that fell in Baines' time is still growing leaves today.

Ghana

At Saakpuli in northern Ghana, a group of large baobabs marks a 19th-century slave transit camp. Slaves were chained to these trees. Similarly, two trees in Salaga in central Ghana remind people of the slave trade. One, at the former slave market, was replanted where slaves were once shackled. A second, larger tree marks the slave cemetery.

India

Inside the Golconda Fort in Hyderabad, India, there is a baobab tree estimated to be 430 years old. It is the largest baobab tree found outside of Africa.

Madagascar

The African baobab in Mahajanga, Madagascar, had a circumference of 21 meters (about 69 feet) by 2013. It became a symbol of the city and was once a place for important meetings and even executions.

Mozambique

The Lebombo Eco Trail tree is about 18.5 meters (about 61 feet) tall with a diameter of almost 22 meters (about 72 feet). It was found to be about 1400 years old. It is made of five stems that grew together, leaving a large hollow space in the middle.

Namibia

The Ombalantu baobab in Namibia has a hollow trunk that can fit about 35 people. It has been used as a chapel, post office, house, and even a hiding place. The Holboom baobab is another tree with a hollow core. It measures 35.10 meters (about 115 feet) around and is about 1750 years old.

Republic of the Congo

The Arbre de Brazza is a baobab in the Republic of the Congo where de Brazza and his friends stopped in 1877. Their carving "EB 1887" is still there.

Senegal

The first scientific description of A. digitata was based on a tree on the island of Sor, Senegal. On a nearby island, Adanson found a baobab with carvings from sailors, including Prince Henry the Navigator in 1444. This tree is no longer there. The Gouye Ndiouly or Guy Njulli might be the oldest baobab in Senegal and the northern hemisphere. This partially collapsed tree, from which new stems have grown, is near the Saloum River. It was once a place for an annual festival where rulers showed loyalty to the king. From 1593 to 1939, 49 kings were crowned at this tree.

US Virgin Islands

The Grove Place Baobab, listed as a Champion Tree, is thought to be the oldest (250–300 years) of about 100 baobabs on Saint Croix in the US Virgin Islands. It is a living reminder of African presence, as its seeds were likely brought by an African slave in the 18th century. It has been a gathering place for plantation workers and unions.

Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe’s Big Tree, near Victoria Falls, is 25 meters (about 82 feet) tall and visited by many tourists. Radiocarbon dating shows it is made of several stems of different ages, with the oldest being about 1150 years old.

| Notable extant specimens | ||

|---|---|---|

| Specimen | Location | Coordinate |

| Kumana Baobab | southern Kruger Park, South Africa | 24°37′06″S 31°47′13″E / 24.61833°S 31.78694°E |

| Gannahoek Baobab | near Thabazimbi, South Africa | 24°26′17″S 27°08′47″E / 24.43806°S 27.14639°E |

| Glencoe Baobab (2009 split) | near Hoedspruit, South Africa | 24°22′25″S 30°51′24″E / 24.37361°S 30.85667°E |

| Briscoe's Baobab | central Kruger Park, South Africa | 24°02′39″S 31°51′40″E / 24.04417°S 31.86111°E |

| Big Baobab Leydsdorp | Leydsdorp-Gravellotte, Limpopo, South Africa | 23°57′26″S 30°34′30″E / 23.95722°S 30.57500°E |

| Von Wielligh's Baobab | central Kruger Park, South Africa | 23°56′27″S 31°43′05″E / 23.94083°S 31.71806°E |

| Sunland Baobab (2016 & 2017 splits) | near Modjadjiskloof, South Africa | 23°37′16″S 30°11′53″E / 23.62111°S 30.19806°E |

| King of Ga-Ratjeke | between Modjadjiskloof and Giyani, South Africa | 23°29′55″S 30°30′06″E / 23.49861°S 30.50167°E |

| Baobab Lane (planted 1933/34) | between Tom Burke and Marnitz, South Africa | 23°07′45″S 28°07′28″E / 23.12917°S 28.12444°E |

| Big Tree | in Blouberg Nature Reserve, South Africa | 22°59′48″S 29°04′20″E / 22.99667°S 29.07222°E |

| Buffelsdrift Baobab | near Swartwater, South Africa | 22°51′41″S 28°13′30″E / 22.86139°S 28.22500°E |

| Sagole Baobab | near Tshipise, South Africa | 22°30′00″S 30°38′00″E / 22.50000°S 30.63333°E |

| Chapman's Baobab / Seven Sisters (2016 split) | Ntwetwe pan, south of Gweta, Botswana | 20°29′25″S 25°14′58″E / 20.49028°S 25.24944°E |

| Blue Bay Baobab | Blue Bay, Mauritius | 20°25′53″S 57°42′57″E / 20.43139°S 57.71583°E |

| Green's Baobab | 27 km south of Gweta, Botswana | 20°25′31″S 25°13′52″E / 20.42528°S 25.23111°E |

| Baines' Baobabs / Sleeping Sisters | north of Gweta, Botswana | 20°06′44″S 24°46′09″E / 20.11222°S 24.76917°E |

| Nxai Pan Baobab (western shore) | north of Gweta, Botswana | 19°53′46″S 24°43′15″E / 19.89611°S 24.72083°E |

| Nxai Pan Baobabs | north of Gweta, Botswana | 19°52′42″S 24°47′21″E / 19.87833°S 24.78917°E |

| Holboom | Naye-Naye Concession, Otjozondjupa Region, Namibia | 19°40′41″S 20°37′05″E / 19.67806°S 20.61806°E |

| Dorslandboom | Mangetti, north of Tsumkwe, Namibia | 19°25′07″S 20°35′37″E / 19.41861°S 20.59361°E |

| Giant Baobab Tree (national monument) | Die Park, Otjozondjupa Region, Namibia | 18°53′10″S 18°19′38″E / 18.88611°S 18.32722°E |

| Savuti Baobab Island | Savuti Plains, Chobe, Botswana | 18°32′19″S 24°06′28″E / 18.53861°S 24.10778°E |

| Sinamatella Road Baobab | Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe | 18°31′51″S 26°24′53″E / 18.53083°S 26.41472°E |

| Ngoma Bridge baobabs | Chobe Forest Reserve, Botswana | 17°55′34″S 24°43′09″E / 17.92611°S 24.71917°E |

| Big Tree | near Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe | 17°54′45″S 25°50′28″E / 17.91250°S 25.84111°E |

| Okahao Baobab | Okahao, Namibia | 17°53′38″S 15°03′59″E / 17.89389°S 15.06639°E |

| Sir Howard's baobab | Tsandi, Namibia | 17°44′51″S 14°53′41″E / 17.74750°S 14.89472°E |

| Ombalantu Baobab | Outapi, northern Namibia | 17°30′43″S 14°59′16″E / 17.51194°S 14.98778°E |

| Hollow Mubuyu Tree | Katima Mulilo, Namibia | 17°29′19″S 24°16′42″E / 17.48861°S 24.27833°E |

| Kondanamwali | Kafue N.P., Zambia | ca. 16°19′49″S 25°55′29″E / 16.33028°S 25.92472°E |

| Mahajanga / Majunga baobab | Mahajanga, Madagascar | 15°43′17″S 46°18′18″E / 15.72139°S 46.30500°E |

| Porto de Galinhas Baobabs | Porto de Galinhas, PE, Brazil | 08°30′04″S 35°00′31″W / 8.50111°S 35.00861°W |

| Stanley's Baobab | Boma, DRC | 05°51′34″S 13°03′21″E / 5.85944°S 13.05583°E |

| Poet's Boabab | Natal, RN, Brazil | 05°48′20″S 35°12′34″W / 5.80556°S 35.20944°W |

| L'arbre de Brazza | near Dolisie, Niari, Republic of the Congo | 04°11′07″S 12°35′50″E / 4.18528°S 12.59722°E |

| Mombasa Baobab Forest | Mombasa, Kenya | 04°04′42″S 39°40′01″E / 4.07833°S 39.66694°E |

| Lugard's Baobab | near Lokoja, Nigeria | 07°49′11″N 06°44′07″E / 7.81972°N 6.73528°E |

| Aliya-gaha / Elephant tree | Gangewadiya basin, Wilpattu N.P., Sri Lanka | ca. 8°17′41″N 79°50′50″E / 8.29472°N 79.84722°E |

| Salaga slave market baobab | Salaga, Ghana | ca. 8°33′00″N 0°31′15″W / 8.55000°N 0.52083°W |

| Salaga slave cemetery baobab | Salaga, Ghana | ca. 8°33′N 0°31′W / 8.550°N 0.517°W |

| Pallimunai Baobab Tree | Pallimunai, Mannar District, Sri Lanka | 08°58′54″N 79°55′24″E / 8.98167°N 79.92333°E |

| Delft Island baobab | Neduntheevu, Jaffna District, Sri Lanka | 09°30′45″N 79°42′55″E / 9.51250°N 79.71528°E |

| Saakpuli slave camp baobabs | Saakpuli, near Pigu, Ghana | 10°01′27″N 0°46′02″W / 10.02417°N 0.76722°W |

| Kuka Katsi | Durbi Takusheyi, Nigeria | 12°56′45″N 07°52′55″E / 12.94583°N 7.88194°E |

| Gouye Ndiouly | Kahone, Kaolack Region, Senegal | ca. 14°08′37″N 16°00′27″W / 14.14361°N 16.00750°W |

| Baak no Maad / King’s Baobab | Joal-Fadiouth, Thiès Region, Senegal | 14°09′12″N 16°49′25″W / 14.15333°N 16.82361°W |

| Baobab Sacré | Fadial, Thiès Region, Senegal | 14°10′25″N 16°46′39″E / 14.17361°N 16.77750°E |

| Dakfao sacred baobab | Dakfao, Niger | 14°12′03″N 03°16′11″E / 14.20083°N 3.26972°E |

| Corniche Est baobab | East Corniche Road, Dakar, Senegal | 14°39′52″N 17°25′55″W / 14.66444°N 17.43194°W |

| Savanur Baobabs | Savanur, India | 14°58′41″N 75°20′00″E / 14.97806°N 75.33333°E |

| St. Maryam Dearit Shrine | near Keren, Eritrea | 15°47′40″N 38°28′06″E / 15.79444°N 38.46833°E |

| João Barrosa Baobabs | João Barrosa, Boa Vista, Cape Verde | 16°01′08″N 22°44′31″W / 16.01889°N 22.74194°W |

| Mirbat Baobab Forest | near Mirbat, Dhofar, Oman | 17°03′11″N 54°36′39″E / 17.05306°N 54.61083°E |

| Hatiyan Jhad Baobab Tree | Naya Qila, Golconda Fort, Hyderabad, India | 17°23′34″N 78°24′39″E / 17.39278°N 78.41083°E |

| Nanakramguda Baobab Tree | Nanakramguda, Hyderabad, India | 17°25′26″N 78°20′40″E / 17.42389°N 78.34444°E |

| Grove Place Baobab | Grove Place, Saint Croix, US Virgin Islands | 17°43′34″N 64°49′28″W / 17.72611°N 64.82444°W |

| Diu Rukhda Baobab | Diu Island, Nagao Beach, Gujarat, India | 20°42′16″N 70°54′18″E / 20.70444°N 70.90500°E |

| Zaymi Baobab | Zaymi, Al Batinah, Oman | 24°27′16″N 56°16′41″E / 24.45444°N 56.27806°E |

| Mallanimli Baobab | Orchha, Madhya Pradesh, India | 25°21′51″N 78°38′32″E / 25.36417°N 78.64222°E |

| Parijaat Tree | Kintoor, Uttar Pradesh, India | 27°01′35″N 81°28′43″E / 27.02639°N 81.47861°E |

Images for kids

-

In full leaf at Bagamoyo, Tanzania

See also

In Spanish: Baobab africano para niños

In Spanish: Baobab africano para niños

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |