History of Georgia (country) facts for kids

The country of Georgia (Georgian: საქართველო sakartvelo) was first united as a kingdom by King Bagrat III of Georgia in the early 11th century. It grew from older kingdoms like Colchis and Iberia. The Kingdom of Georgia became very strong between the 10th and 12th centuries under King David IV the Builder and Queen Tamar the Great.

However, Georgia was later invaded by the Mongols in 1243. After a short time of being united again under George V the Brilliant, it faced invasions from the Timurid Empire. By 1490, Georgia split into many smaller kingdoms and regions. For centuries, these parts of Georgia fought to stay independent from the Ottoman and Iranian empires. In the 19th century, Russia took control of Georgia.

Georgia had a short period of independence as the Democratic Republic of Georgia from 1918 to 1921. Then, it became part of the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic (1922–1936) and later the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic until the Soviet Union broke apart.

Today, the country of Georgia has been independent since 1991. Its first president, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, wanted to make Georgia stronger. But he was removed from power in a civil war that lasted until 1995. Two regions, Abkhazia and South Ossetia, became independent from Georgia with support from Russia. In 2003, the Rose Revolution led to President Eduard Shevardnadze stepping down. The new government, led by Mikheil Saakashvili, stopped another region, Adjara, from breaking away in 2004. However, problems with Abkhazia and South Ossetia led to the 2008 war with Russia, and tensions still remain.

The history of Georgia is closely connected to the story of the Georgian people.

Contents

- Ancient Times

- Medieval Georgia: The Golden Age

- Queen Tamar: Peak of Power

- Invasions and Decline

- Early Modern Period

- Russian Annexations

- Modern History

- Images for kids

- See also

Ancient Times

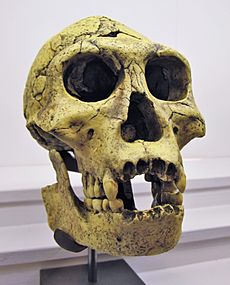

People have lived in Georgia for a very long time, with the oldest signs found at Dmanisi dating back about 1.8 million years. This makes it the oldest place where humans have been found in Europe. Later, people lived in caves and open areas during the Stone Age.

Around 6000 to 5000 BC, people in Georgia started farming. This was part of the Shulaveri-Shomu culture. They used local obsidian for tools, raised animals like cows and pigs, and grew crops, including grapes. In fact, the oldest evidence of wine making, from 8000 years ago, has been found in Georgia.

People in Georgia also started working with metals around 6000 BC. By 4000 BC, metals were used much more widely across the region. Ancient homes with special designs, like a central pillar and chimney, have been found from the 5th millennium BC. These designs influenced later Georgian houses.

The first groups of early Georgians, called Diauehi, are mentioned in history around 1200 BC. Ancient findings show that early political groups with advanced metalworking skills existed by the 7th century BC. Between 2100 and 750 BC, the area faced invasions from groups like the Hittites and Medes. During this time, the early Georgian language groups split into different branches, leading to modern Georgian, Svan, Megrelian, and Laz languages.

By the end of the 8th century BC, two main Georgian states had formed: the Kingdom of Colchis in the west and the Kingdom of Iberia in the east.

Classical Period: Early Georgian Kingdoms

The classical period saw these early Georgian states grow. In the 4th century BC, a united kingdom of Georgia was formed, showing an advanced way of organizing a state with one king and noble leaders.

In Greek mythology, Colchis was famous as the home of the sorceress Medea and the legendary Golden Fleece. Jason and the Argonauts traveled there to find it. Some scholars believe the myth of the Golden Fleece came from the practice of using sheep fleeces to collect gold dust from mountain rivers in western Georgia. Colchis was also known as Egrisi or Lazica and was a battleground between the Byzantine Empire and Persia.

In 66 BC, the Roman Empire took control of the Caucasus region. Colchis became a Roman province. Iberia, however, became a vassal kingdom, meaning it was protected by Rome but kept much of its independence. This was helpful for Iberia, as it got protection from fierce mountain tribes. For nearly 400 years, these early Georgian kingdoms were often allies or client states of Rome.

From the first centuries AD, different beliefs like Mithraism, paganism, and Zoroastrianism were common in Georgia. In the 4th century, a Roman woman named Saint Nino began teaching about Christianity. She helped the queen get better from an illness and convinced her to become Christian. Then, St. Nino also convinced King Mirian III to accept Christianity. In 337 AD, King Mirian officially made Christianity the state religion. This was a huge step that helped Georgian literature and art grow and played a key role in forming the Georgian nation. By accepting Christianity, Georgia became closely tied to the Eastern Roman Empire, which greatly influenced Georgia's culture for almost a thousand years.

Medieval Georgia: The Golden Age

Georgia Becomes United

In the early 9th century, a new Georgian state began to rise in a region called Tao-Klarjeti. Ashot Courapalate from the royal Bagrationi dynasty freed these lands from Arab control. These areas were officially part of the Byzantine Empire, but in reality, they acted as an independent country. The Bagrationi family ruled this region for almost a century.

The first united Georgian kingdom was formed at the end of the 10th century. This happened when Curopalate David took control of Kartli-Iberia. A few years later, Bagrat III inherited the throne of Abkhazia. In 1001, Bagrat also gained Tao-Klarjeti. Then, from 1008 to 1010, he added Kakheti and Ereti to his lands. This made him the first king to unite all of Georgia, both east and west.

The second half of the 11th century brought a big challenge: the invasion of the Seljuk Turks. By the 1040s, the Seljuks had built a huge empire. In 1071, the Seljuk army defeated the combined Byzantine, Armenian, and Georgian forces at the Battle of Manzikert. By 1081, most of Georgia was conquered and destroyed by the Seljuks. Only the mountainous areas remained free. Cities and fortresses were ruined, villages were looted, and many people were killed. By the late 1080s, the Seljuks outnumbered Georgians in the region.

King David IV the Builder

The rule of David IV (also called "the Builder" or "the Great") marked the start of the Georgian Golden Age. He became king at 16 during the Seljuk invasions. With help from his minister, George of Chqondidi, David IV brought the feudal lords under control and centralized power. This helped him deal with foreign threats. In 1121, he famously defeated much larger Turkish armies at the Battle of Didgori. The Georgian cavalry chased the fleeing Turks for days, capturing many treasures and prisoners. This victory secured Tbilisi and began a new era of growth.

To show Georgia's higher status, David IV was the first Georgian king to refuse the respected titles given by the Eastern Roman Empire, Georgia's old ally. This showed that Georgia now saw itself as an equal. He also focused on removing unwanted Eastern influences and promoting traditional Christian and Byzantine culture. As part of this, he founded the Gelati Monastery, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, which became an important center for learning in the Eastern Orthodox Christian world.

David also wrote religious songs called Hymns of Repentance. In these songs, he saw himself like the Biblical David, with a similar connection to God and his people. His hymns also showed a strong desire to fight against the Seljuks, similar to the European crusaders of his time.

Kings Demetrius I and George III

The kingdom continued to do well under Demetrius I, David's son. Even with some family conflicts over who would rule next, Georgia remained a strong country with a powerful army. Demetrius won several important battles against Muslim forces in Ganja. He even took the gates of Ganja as a trophy to Gelati.

Demetrius was also a talented poet and continued his father's work in Georgian religious music. His most famous hymn, Thou Art a Vineyard, is dedicated to the Virgin Mary, who is Georgia's patron saint. It is still sung in Georgian churches today.

Demetrius's son, George, became king in 1156. He started a more aggressive foreign policy. The same year he became king, George launched a successful campaign against the Seljuk sultanate of Ahlat. He freed the important Armenian town of Dvin from Turkish control and was seen as a hero there. George also continued to connect Georgian royalty with the highest levels of the Eastern Roman Empire. His daughter Rusudan married Manuel Komnenos, the son of Emperor Andronikos I Komnenos.

Queen Tamar: Peak of Power

The achievements of the previous kings were built upon by Queen Tamar, daughter of George III. She was the first female ruler of Georgia in her own right. Under her leadership, Georgia reached its greatest power and fame in the Middle Ages. She protected her empire from Turkish attacks and settled internal problems, including a rebellion led by her Russian husband, Yury Bogolyubsky. She also made very fair laws for her time, like ending the death penalty and torture.

Foreign Actions and the Holy Land

One important event during Tamar's rule was the creation of the empire of Trebizond on the Black Sea in 1204. This state was formed in the northeast of the weakening Byzantine Empire with help from Georgian armies. They supported Alexios I of Trebizond and his brother, David Komnenos, who were Tamar's relatives and had been raised in Georgia.

Georgia's power grew so much that in Tamar's later years, the kingdom focused on protecting Georgian monasteries in the Holy Land. Eight of these were in Jerusalem. A writer for Saladin, the Muslim leader, reported that after Saladin conquered Jerusalem in 1187, Tamar sent messengers to ask for the return of property taken from Georgian monasteries. Her efforts seemed to work.

Jacques de Vitry, a Christian leader in Jerusalem at the time, wrote about the Georgians:

There is also in the East another Christian people, who are very warlike and valiant in battle, being strong in body and powerful in the countless numbers of their warriors...Being entirely surrounded by infidel nations...these men are called Georgians, because they especially revere and worship St. George...Whenever they come on pilgrimage to the Lord's Sepulchre, they march into the Holy City...without paying tribute to anyone, for the Saracens dare in no wise molest them...

Trade and Culture Flourish

With important trade centers now under Georgia's control, business and industry brought new wealth to the country and Tamar's court. Money from neighbors and war spoils filled the royal treasury. This led to a saying that "the peasants were like nobles, the nobles like princes, and the princes like kings."

Tamar's reign also saw continued artistic growth. While Georgian writings still focused on Christian values, non-religious literature became very popular. This led to the famous epic poem The Knight in the Panther's Skin (Vepkhistq'aosani), written by Georgia's national poet Rustaveli. This poem is seen as the greatest achievement of Georgian literature. It celebrates ideals like chivalry, friendship, and courtly love.

Invasions and Decline

Around the time the Mongols invaded Eastern Europe, they also moved south into Georgia. King George IV, Queen Tamar's son, stopped his plans to help the Crusades and focused on fighting the invaders. But the Mongol attack was too strong. Georgians suffered heavy losses, and the king himself was badly hurt. George died young at 31.

George's sister, Rusudan, became queen, but she was not experienced enough, and her country was too weak to push out the Mongols. In 1236, a Mongol commander named Chormaqan led a huge army against Georgia. Queen Rusudan had to flee to the west, leaving eastern Georgia to make peace with the Mongols and agree to pay tribute. Those who fought back were completely destroyed. The Mongols did not cross the mountains into western Georgia, saving it from widespread destruction. In 1243, Georgia was finally forced to accept the Great Khan as its ruler.

The decades of fighting against the Mongols caused even more damage to Georgia than the initial invasions. The first uprising against the Mongols started in 1259 under David VI and lasted for almost 30 years. Other kings, like Demetrius the Self-Sacrificer (who was executed by the Mongols) and David VIII, also continued the fight without much success.

Georgia finally saw a period of recovery under King George V the Brilliant. He took advantage of the weakening Mongol empire, stopped paying tribute, and brought back Georgia's borders from before 1220. He also brought the Empire of Trebizond back under Georgia's influence. Under King George V, Georgia developed strong trade ties with the Byzantine Empire and European cities like Genoa and Venice. He also managed to get several Georgian monasteries in Jerusalem back for the Georgian Orthodox Church and secured safe passage for Georgian pilgrims to the Holy Land. The Jerusalem cross, which is now on the modern flag of Georgia, is thought to have become popular during his reign.

After George V died, the unified Kingdom of Georgia began to decline. The next decades brought the Black Death, spread by nomads, and many invasions led by Tamerlane. These events destroyed Georgia's economy, population, and cities. After the fall of Byzantium, Georgia became an isolated Christian country, surrounded by hostile Muslim empires.

Early Modern Period

Outside Control

In the 15th century, the entire region changed greatly. The Kingdom of Georgia became an isolated Christian area, surrounded by a Muslim world. For the next three centuries, Georgian rulers tried to keep their independence while being under the control of the Turkish Ottoman and Iranian Safavid, Afsharid, and Qajar empires. Sometimes, they were just puppets controlled by these powerful rulers.

By the mid-15th century, most of Georgia's old neighboring states had disappeared. The fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453 cut off Christian states in the area from Europe. Georgia stayed connected to the West through Genoese colonies in the Crimea.

Because of these changes, the Georgian Kingdom faced economic and political problems. In the 1460s, the kingdom split into several smaller kingdoms and regions:

- 3 Kingdoms: Kartli, Kakheti, and Imereti.

- 5 Principalities: Guria, Svaneti, Meskheti, Abkhazeti, and Samegrelo.

By the late 15th century, the Ottoman Empire was moving into Georgian lands from the west. In 1501, a new Muslim power, Safavid Iran, rose in the east. For centuries, Georgia became a battleground between these two great powers. Georgian states tried to keep their independence in different ways. In 1555, the Ottomans and Safavids signed the Peace of Amasya, dividing Georgia into spheres of influence: Imereti in the west went to the Turks, and Kartli-Kakheti in the east went to the Persians. However, this treaty did not last long.

Since at least the mid-15th century, Georgian rulers often asked for help from Western European powers, but they usually did not get it. One example was in the early 1700s, when a Georgian diplomat named Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani was sent by King Vakhtang VI to France and the Vatican to get help for Georgia. Orbeliani was welcomed by King Louis XIV and Pope Clement XI, but no real help was given. This lack of Western support left Georgia vulnerable. Orbeliani and King Vakhtang were eventually forced to seek protection from Peter the Great of Russia and fled there, never returning. In modern Georgia, Orbeliani's mission became a symbol of how the West sometimes ignores Georgia's pleas for protection.

After the Ottomans failed to keep a strong hold in the eastern Caucasus, the Iranians tried to strengthen their control over the rebellious kingdoms of Eastern Georgia. For the next 150 years, as Persian subjects, various Georgian kings and nobles rebelled. At other times, they accepted Persian rule, and many even converted to Islam to gain favors from the Iranian Shahs.

In the early 17th century, Shah Abbas I launched a harsh campaign into his Georgian territories. This was after he learned that Teimuraz I of Kakheti and some Christians had attacked and killed the governor of Karabakh. Shah Abbas sent his troops to Georgia in 1616 to stop the Georgian revolt in Tbilisi. However, the Safavid soldiers faced strong resistance from the people of Tbilisi. Angered, Shah Abbas ordered a massacre of the public. Many Georgian soldiers and people were killed, and between 130,000 and 200,000 Georgians from Kakheti were sent away to Persia. During this conflict, Teimuraz sent the Queen mother, Ketevan, to negotiate with Abbas. But in revenge for Teimuraz's defiance, Abbas ordered the queen to give up Christianity. When she refused, he had her killed. By the 17th century, both eastern and western Georgia were poor due to constant warfare. The economy was so bad that people used bartering instead of money, and city populations greatly decreased.

Georgia and Russia Before 1801

By the 16th century, the Kingdom of Georgia had broken into smaller states, which were fought over by the Ottoman Empire and Persia. Soon, the Russian state of Muscovy became a third powerful empire in the region. Because Russia shared Georgia's Orthodox Christian religion, Georgia increasingly looked to the north for help. Talks between Georgia and Moscow began in 1558. In 1589, Tsar Fyodor II offered to protect the kingdom. However, little help came, and Russia was still too far from Georgia to truly challenge Ottoman power.

Only in the early 18th century did Russia begin to make serious military moves south of the Caucasus. In 1722, Peter the Great took advantage of chaos in Persia to lead an expedition and formed an alliance with the Georgian king Vakhtang VI. But the Georgian and Russian armies failed to meet up, and the Russians retreated north again, leaving Georgia vulnerable to the Persians. Vakhtang ended his life in exile in Russia.

Vakhtang's successor, Heraclius II of Georgia, also turned to Russia for protection against Ottoman and Persian attacks. The kings of Imereti (in Western Georgia) also sought Russian protection against the Ottomans. The Russian empress Catherine the Great wanted Georgians as allies in her wars but sent only small forces to help them. In 1783, Heraclius signed the Treaty of Georgievsk with Russia. This treaty meant Kartli-Kakheti would only be loyal to Russia in return for Russian protection. But when another war with Turkey started in 1787, the Russians pulled their troops out of Georgia, leaving it unprotected. In 1795, the new Persian shah, Agha Mohammed Khan, told Heraclius to break ties with Russia or face invasion. Heraclius ignored him, expecting Russian help that never arrived. Agha Muhammad Khan then attacked, capturing and burning the capital, Tbilisi, to the ground.

Russian Annexations

Eastern Georgia Joins Russia

After Heraclius II died, his sick son George XII became king. He died just two years later in 1800. George's death led to a fight over who would be the next king. However, Tsar Paul I had already decided that Georgia would no longer have a king. Instead, Russia would rule the country directly. He signed a decree to make Eastern Georgia part of the Russian Empire, which Tsar Alexander I confirmed on September 12, 1801.

In May 1801, Russian General Carl Heinrich von Knorring removed the Georgian heir to the throne, Davit Batonishvili, from power. He set up a temporary government led by General Ivan Petrovich Lazarev. Knorring had secret orders to send all male and some female members of the Georgian royal family to Russia. Some Georgian nobles did not accept this until April 1802, when General Knorring gathered them in Tbilisi's Sioni Cathedral and forced them to swear loyalty to the Russian Empire. Those who refused were arrested.

Now that Russia could use Georgia as a base to expand further south, Persia and the Ottoman Empire felt threatened. In 1804, Pavel Tsitsianov, the Georgian commander of Russian forces, attacked Ganja. This started the Russo-Persian War (1804-1813). This was followed by the Russo-Turkish War (1806-1812) with the Ottomans, who were unhappy with Russia's expansion in Western Georgia. Both wars ended with Russia winning. The Ottomans and Persians recognized Russia's control over Georgia.

Western Georgia Joins Russia

Solomon II of Imereti was angry about Russia taking over Kartli-Kakheti. He offered a deal: he would make Imereti a Russian protectorate if Russia restored the monarchy and independence of his neighbor. Russia did not reply. In 1803, the ruler of Mingrelia, a region of Imereti, rebelled against Solomon and accepted Russia as his protector. When Solomon refused to make Imereti a Russian protectorate, the Russian general Tsitsianov invaded. On April 25, 1804, Solomon signed a treaty making him a Russian vassal.

However, Solomon was not easily controlled. When war broke out between the Ottomans and Russia, Solomon started secret talks with the Ottomans. In February 1810, Russia declared Solomon dethroned and ordered the people of Imereti to pledge loyalty to the tsar. A large Russian army invaded, but many Imeretians fled to the forests to start a resistance movement. Solomon hoped Russia, busy with its wars, would let Imereti be independent. The Russians eventually crushed the uprising but could not catch Solomon. However, Russia's peace treaties with Ottoman Turkey (1812) and Persia (1813) ended the king's hopes for foreign support. Solomon died in exile in Trabzon in 1815.

In 1828-1829, another Russo-Turkish War ended with Russia gaining the important port of Poti and the fortresses of Akhaltsikhe and Akhalkalaki in Georgia. From 1803 to 1878, through many wars against the Ottoman Empire, several of Georgia's lost territories, like Adjara, were also added to the Russian Empire. The region of Guria was taken over in 1829, and Svaneti was gradually annexed by 1858. Mingrelia, though a Russian protectorate since 1803, was not fully absorbed until 1867.

Modern History

Under the Russian Empire

Russian and Georgian societies had much in common. Both were mainly Orthodox Christian, and in both countries, land-owning nobles ruled over a population of serfs (peasants tied to the land). The Russian authorities wanted to make Georgia part of their empire. At first, Russian rule was harsh and ignored local laws and customs. This led to a plot by Georgian nobles in 1832 and a revolt by peasants and nobles in Guria in 1841.

Things improved when Mikhail Vorontsov became the Viceroy of the Caucasus in 1845. His new policies won over the Georgian nobility, who started to adopt Western European customs, just like Russian nobles had done. However, life for Georgian serfs was very different. They lived in great poverty and often faced starvation. Few lived in towns, where most trade and industry were controlled by Armenians, whose ancestors had moved to Georgia centuries ago.

Serfdom was ended in Russian lands in 1861. The tsar also wanted to free the serfs in Georgia, but he did not want to lose the loyalty of the nobles, who depended on peasant labor. This required careful talks before serfdom was slowly ended in Georgian provinces starting in 1864.

Rise of the National Movement

Ending serfdom did not make either the serfs or the nobles happy. The serfs were still poor, and the nobles lost some of their special rights. Nobles also felt threatened by the growing power of the Armenian middle class in Georgian cities, who became rich as capitalism developed. Georgian unhappiness with Russian rule and Armenian economic power led to a national liberation movement in the second half of the 19th century.

A large peasant revolt happened in 1905, which led to political changes that eased tensions for a while. During this time, the Marxist Social Democratic Party became the most important political group in Georgia. They won all the Georgian seats in the Russian State Duma (parliament) created after 1905. Josef Vissarionovich Djugashvili, better known as Joseph Stalin, was a Georgian Bolshevik who became a leader of the revolutionary movement in Georgia. He later went on to control the Soviet Union.

Many Georgians were upset that the Georgian Orthodox Church lost its independence. Russian clergy took control of Georgian churches and monasteries. They banned the use of Georgian church services and damaged old Georgian frescoes in churches across Georgia.

Between 1855 and 1907, the Georgian patriotic movement was led by Prince Ilia Chavchavadze, a famous poet, writer, and speaker. Chavchavadze funded new Georgian schools and supported the Georgian national theater. In 1877, he started the newspaper Iveria, which was very important in bringing back Georgian national pride. His fight for national awakening was supported by leading Georgian thinkers of that time, such as Giorgi Tsereteli, Ivane Machabeli, Akaki Tsereteli, Niko Nikoladze, Alexander Kazbegi, and Iakob Gogebashvili.

The Georgian intellectuals' support for Prince Chavchavadze and Georgian independence is shown in this statement:

Our patriotism is of course of an entire different kind: it consists solely in a sacred feeling towards our mother land: ... in it there is no hate for other nations, no desire to enslave anybody, no urge to impoverish anybody. Out patriots' desire to restore Georgia's right to self-government and their own civic rights, to preserve their national characteristics and culture, without which no people can exist as a society of human beings.

The last decades of the 19th century saw a great revival in Georgian literature. Writers emerged who were as talented as those during the Golden Age of Rustaveli seven hundred years before. Ilia Chavchavadze himself was excellent in poetry, novels, short stories, and essays. Besides Chavchavadze, the most talented writer of that time was Akaki Tsereteli, known as "the immortal nightingale of the Georgian people." Along with Niko Nikoladze and Iakob Gogebashvili, these writers greatly helped the national cultural revival and are known as the founding fathers of modern Georgia.

First Republic Under German-British Protection

The Russian Revolution of October 1917 caused Russia to fall into a bloody civil war. During this time, several Russian territories declared independence. Georgia was one of them, declaring itself the independent Democratic Republic of Georgia (DRG) on May 26, 1918. All major European powers recognized it. The DRG had a moderate, multi-party political system led by the Georgian Social Democratic Party. This was very different from the "dictatorship" set up by the Bolsheviks in Russia.

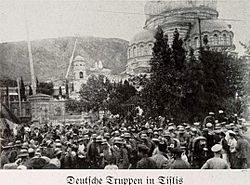

To keep its new independence and protect itself from both Russia and Turkey, Georgia became a protectorate of the German Empire. Germany sent troops under General Friedrich Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein. Germany's involvement was short but effective. Berlin pressured Turkey to respect Georgia's borders, and by July 1918, Turkey handed over all Georgian ports and railways it had controlled. Germany also loaned millions of Deutschmarks to the new republic. Despite friendly relations, Germany had to leave Georgia after losing World War I.

After Germany's defeat, Georgia came under British protection. A British battalion landed in Poti, Georgia on January 4, 1919, and then in Batumi. Britain also took over the management and protection of Georgian railways. Britain's goal was different from Germany's. London's main aim was to stop Bolshevik Russia from getting oil fields near Baku. The British General Cooke-Collins seemed to care little about what happened inside Georgia. There was minimal British investment, and the focus was on securing pipelines, trade, and natural resources. Because of this, the British were less liked than the Germans had been. Still, locals saw Britain's presence as a stabilizing force.

The view of Britain began to change with the appointment of Sir Oliver Wardrop as Ambassador to Tbilisi. Wardrop was well-liked by Georgians because of his earlier service as British consul in Russian Imperial Georgia during the 1880s and 1890s. Wardrop had learned Georgian and translated Georgian works. His sister, Marjory Wardrop, was also a scholar of Georgia. She brought awareness of Georgian culture to Britain by making the first English translation of the Georgian epic poem The Knight in the Panther's Skin. British presence coincided with important events. The Georgian–Armenian War, which started over parts of Georgia with Armenian populations, ended in a truce due to British intervention. In 1918–1919, Georgian general Giorgi Mazniashvili led an attack against the White Army to claim the Black Sea coastline for independent Georgia.

Georgian-Armenian War (1918)

During the end of World War I, Armenians and Georgians were defending against the advancing Ottoman Empire. In June 1918, to stop an Ottoman advance on Tiflis, Georgian troops occupied the Lori Province. This area had a 75% Armenian majority at the time. After the Ottomans withdrew, Georgian forces remained. Georgian parliament member Irakli Tsereteli suggested that Armenians would be safer as Georgian citizens. The Georgians offered a conference to solve the issue, but the Armenians refused. In December 1918, fighting began between the two republics.

The Georgian-Armenian War was a border war fought in 1918 between the Democratic Republic of Georgia and the Democratic Republic of Armenia. They fought over parts of the disputed provinces of Lori and Javakheti. These areas had been historically mixed Armenian-Georgian territories but were mostly populated by Armenians in the 19th century.

Red Army Invasion (1921)

In February 1921, the Red Army invaded Georgia. After a short war, they occupied the country. The Georgian government had to flee. Guerrilla resistance continued from 1921 to 1924, followed by a large patriotic uprising in August 1924. Colonel Kakutsa Cholokashvili was one of the most important guerrilla leaders during this time.

Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic (1921–1990)

During the Georgian Affair of 1922, Georgia was forced to join the Transcaucasian SFSR. This republic included Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia (with Abkhazia and South Ossetia). The Soviet government made Georgia give up some areas to Turkey, Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Russia. Soviet rule was harsh. About 50,000 people were killed between 1921 and 1924. More than 150,000 were punished under Stalin and his secret police chief, the Georgian Lavrenty Beria, in later years. In 1936, the Transcaucasian SFSR was dissolved, and Georgia became the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Reaching the Caucasus oilfields was a main goal of Adolf Hitler's invasion of the USSR in June 1941. However, the armies of the Axis powers did not reach Georgia. The country contributed almost 700,000 fighters to the Red Army, and 350,000 of them were killed. Georgia was also a vital source of textiles and weapons. However, some Georgians fought on the side of the German armed forces, forming the Georgian Legion.

During this period, Stalin ordered the deportation of the Chechen, Ingush, Karachay, and Balkarian peoples from the Northern Caucasus. They were sent to Siberia and Central Asia for supposedly working with the Nazis. He ended their autonomous republics. The Georgian SSR was briefly given some of their territory until 1957.

Stalin's call for national unity during the war calmed Georgian nationalism. On March 9, 1956, about a hundred Georgian students were killed when they protested against Nikita Khrushchev's policy of de-Stalinization (removing Stalin's influence).

The decentralization program started by Khrushchev in the mid-1950s was used by Georgian Communist Party officials to build their own power. A thriving unofficial economy grew alongside the official state-owned economy. While Georgia's official economic growth was among the lowest in the USSR, indicators like savings, car ownership, and house ownership were the highest in the Union. This made Georgia one of the most economically successful Soviet republics. Corruption was very high. Among all Soviet republics, Georgia had the highest number of residents with high or special secondary education.

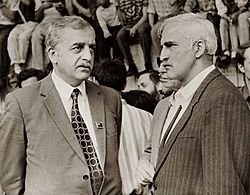

Corruption was common in the Soviet Union, but it became so widespread and obvious in Georgia that it embarrassed the authorities in Moscow. Eduard Shevardnadze, Georgia's interior minister from 1964 to 1972, gained a reputation for fighting corruption. He arranged for the removal of Vasil Mzhavanadze, the corrupt First Secretary of the Georgian Communist Party. Shevardnadze then became First Secretary with Moscow's approval. He was an effective ruler of Georgia from 1972 to 1985, improving the official economy and firing hundreds of corrupt officials.

Soviet power and Georgian nationalism clashed in 1978. Moscow ordered a change to the Georgian constitution that would remove Georgian as the official state language. However, due to pressure from mass street demonstrations on April 14, 1978, Moscow approved Shevardnadze's decision to keep the constitutional guarantee that Georgian was the official language. April 14 was then made the Day of the Georgian Language.

Shevardnadze's appointment as Soviet Foreign Minister in 1985 led to his replacement in Georgia by Jumber Patiashvili. Patiashvili was a conservative and not very effective Communist leader who struggled with the challenges of perestroika (reforms). By the late 1980s, increasingly violent clashes happened between the Communist authorities, the growing Georgian nationalist movement, and nationalist movements in Georgia's minority regions (especially South Ossetia). On April 9, 1989, Soviet troops broke up a peaceful demonstration in Tbilisi. Twenty Georgians were killed, and hundreds were wounded or poisoned. This event made Georgian politics more extreme, leading many, even some Georgian communists, to believe that independence was better than continued Soviet rule.

Independent Georgia

Gamsakhurdia's Presidency (1991-1992)

Opposition to the communist government grew through protests and strikes. This led to a free, multi-party parliamentary election on October 28, 1990. The Round Table/Free Georgia group won 54% of the vote and 155 seats. The communists won 64 seats. The leading activist, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, became the head of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Georgia. On March 31, 1991, Gamsakhurdia quickly organized a referendum on independence, which was approved by 98.9% of voters. Formal independence from the Soviet Union was declared on April 9, 1991. However, it took some time for other countries like the United States and European nations to recognize it. Gamsakhurdia's government strongly opposed any remaining Russian influence, such as Soviet military bases. After the Soviet Union dissolved, his government refused to join the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

Gamsakhurdia was elected president on May 26, 1991, with 86% of the vote. He was later criticized for being an unpredictable and authoritarian leader. Nationalists and reformers joined forces against him. The situation worsened because many former Soviet weapons were available, and paramilitary groups became powerful. On December 22, 1991, armed opposition groups launched a violent military coup d'état. They surrounded Gamsakhurdia and his supporters in government buildings in central Tbilisi. Gamsakhurdia managed to escape and fled to the Russian republic of Chechnya in January 1992.

Shevardnadze's Presidency (1992–2003)

The new government invited Eduard Shevardnadze to lead a State Council in March 1992, making him the de facto president. In August 1992, a separatist conflict in the Georgian region of Abkhazia grew worse when government forces were sent to stop separatist activities. The Abkhaz fought back with help from Russian paramilitary groups. In September 1993, government forces suffered a huge defeat, were driven out, and the entire Georgian population of the region was forced to leave. About 14,000 people died, and 300,000 became refugees.

Ethnic violence also broke out in South Ossetia but was eventually stopped. However, hundreds were killed, and 100,000 refugees fled into Russian North Ossetia. In southwestern Georgia, the region of Ajaria came under the control of Aslan Abashidze. He ruled his republic from 1991 to 2004 almost like his own kingdom, with little influence from the Tbilisi government.

On September 24, 1993, after the disaster in Abkhazia, Zviad Gamsakhurdia returned from exile to organize an uprising against the government. His supporters took advantage of the government's disorganization and quickly took over much of western Georgia. This worried Russia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. Units of the Russian Army were sent to Georgia to help the government. Gamsakhurdia's rebellion quickly failed, and he died on December 31, 1993, seemingly after being trapped by his enemies. In a very controversial agreement, Shevardnadze's government agreed to join the CIS as part of the deal for military and political support.

Shevardnadze barely survived a bomb attack in August 1995. He blamed his former paramilitary allies. He used this chance to imprison the paramilitary leader Jaba Ioseliani and ban his group, the Mkhedrioni, saying it was a strike against "mafia forces." However, his government, and his own family, became increasingly linked to widespread corruption. This hurt Georgia's economic growth. He won presidential elections in November 1995 and April 2000 by large majorities, but there were constant claims of vote-rigging.

The war in Chechnya caused much tension with Russia, which accused Georgia of hiding Chechen fighters. More tension came from Shevardnadze's close relationship with the United States. The US saw him as a way to balance Russian influence in the important Transcaucasus region. Georgia received a lot of US foreign and military aid. It signed a partnership with NATO and stated its goal to join both NATO and the EU. In 2002, the United States sent hundreds of Special Operations Forces to train the Military of Georgia. Perhaps most importantly, Georgia secured a $3 billion project for a Caspian-Mediterranean pipeline (Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline).

A strong group of reformers, led by Mikheil Saakashvili and Zurab Zhvania, united to oppose Shevardnadze's government in the November 2, 2003 parliamentary elections. The elections were widely seen as rigged, even by international observers. In response, the opposition organized huge protests in Tbilisi. After two tense weeks, Shevardnadze resigned on November 23, 2003. Nino Burjanadze temporarily replaced him as president.

These election results were canceled by the Georgia Supreme Court after the Rose Revolution on November 25, 2003. This followed claims of widespread electoral fraud and large public protests, which led to Shevardnadze's resignation.

Saakashvili's Presidency (2004-2013)

- 2004 Elections

A new election was held on March 28, 2004. The National Movement - Democrats (NMD), the party supporting Mikheil Saakashvili, won 67% of the vote. Only the Rightist Opposition (7.6%) also got seats in parliament.

On January 4, Mikheil Saakashvili won the Georgian presidential election, 2004 with a huge majority of 96% of the votes. Constitutional changes were quickly passed in Parliament in February. These changes gave the President more power to dismiss Parliament and created the position of Prime Minister. Zurab Zhvania was appointed Prime Minister. Nino Burjanadze, the temporary President, became Speaker of Parliament.

- First Term (2004-2007)

The new president faced many challenges. More than 230,000 internally displaced persons put a huge strain on the economy. Peace in the separatist areas of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, watched over by Russian and United Nations peacekeepers, remained fragile.

The Rose Revolution created many hopes, both in Georgia and abroad. The new government was expected to bring democracy, end widespread corruption, and regain control over all Georgian territory. These were very big goals. The new leaders focused on giving more power to the executive branch to quickly change the country. The Saakashvili government did achieve impressive results in strengthening the state and fighting corruption. Georgia's ranking in the Corruption Perceptions Index improved greatly. However, these achievements sometimes came from using strong executive powers, which meant less agreement from others.

After the Rose Revolution, relations between the Georgian government and the semi-separatist Ajarian leader Aslan Abashidze quickly worsened. Abashidze rejected Saakashvili's demands for Tbilisi's government to have full control in Ajaria. Both sides prepared for a possible military fight. Saakashvili's strong demands and large street protests forced Abashidze to resign and flee Georgia (2004 Adjara crisis).

Relations with Russia remained difficult because Russia continued to support the separatist governments in Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Russian troops were still stationed at military bases and as peacekeepers in these regions. Saakashvili's public promise to solve the issue caused criticism from the separatist regions and Russia. In August 2004, several clashes happened in South Ossetia.

On October 29, 2004, NATO approved Georgia's Individual Partnership Action Plan (IPAP). Georgia was the first NATO partner country to achieve this.

Georgia supported the coalition forces in the Iraq war. On November 8, 2004, 300 more Georgian troops were sent to Iraq. The Georgian government promised to send a total of 850 troops to Iraq to serve in the UN Mission's protection forces. Along with sending more troops, the US trained an additional 4,000 Georgian soldiers.

In February 2005, Prime Minister Zurab Zhvania died, and Zurab Nogaideli was appointed as the new Prime Minister. Saakashvili was still under pressure to deliver on his promised reforms. Organizations like Amnesty International raised serious concerns about human rights. Unhappiness over unemployment, pensions, corruption, and the ongoing dispute over Abkhazia greatly reduced Saakashvili's popularity.

In 2006, Georgia's relationship with Russia was at its lowest point due to a Georgian-Russian spying dispute and related events. In 2007, a political crisis led to serious anti-government protests, and Russia allegedly violated Georgia's airspace several times.

- 2007 Crisis

After the police crackdown on the 2007 protests, Saakashvili's government focused on its successful economic reforms. Kakha Bendukidze was key to these reforms, which included one of the least restrictive labor laws, low flat income tax rates (12%), and some of the lowest customs rates worldwide. The goal of the Georgian leaders became "a functioning democracy with the highest possible level of economic liberties," as Prime Minister Lado Gurgenidze said.

Saakashvili called for new parliamentary and presidential elections for January 2008. To run for president, Saakashvili announced his resignation on November 25, 2007. Nino Burjanadze became acting president for a second time until Saakashvili was re-elected on January 20, 2008.

- Second Term (2008-2013)

In August 2008, Russia and Georgia fought in the 2008 South Ossetia war. The aftermath of this war, which led to the 2008–2010 Georgia–Russia crisis, is still tense.

In October 2012, Saakashvili admitted his party lost the parliamentary elections. He stated that "the opposition has the lead and it should form the government - and I as president should help them with this." This was the first peaceful transfer of power in Georgia's history since the Soviet Union broke up.

Margvelashvili's Presidency (2013-present)

On November 17, 2013, Giorgi Margvelashvili won the Georgian presidential election, 2013 with 62.12% of the votes. With his election, a new constitution came into effect. This constitution shifted significant power from the President to the Prime Minister. Margvelashvili's inauguration was not attended by his predecessor, Mikheil Saakashvili, who said it was due to disrespect from the new government.

Margvelashvili initially refused to move into the luxurious presidential palace built under Saakashvili in Tbilisi. He chose more modest offices until a 19th-century building, once the U.S. embassy, could be renovated for him. However, he later started to use the palace occasionally for official ceremonies. This was one reason why former Prime Minister Ivanishvili publicly criticized Margvelashvili in March 2014, saying he was "disappointed" in him.

Images for kids

-

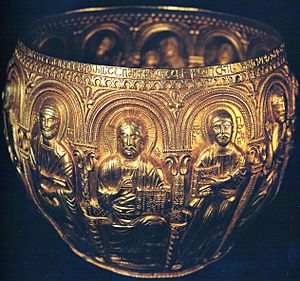

Patera showing Marcus Aurelius found in central Georgia, 2nd century AD.

-

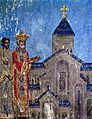

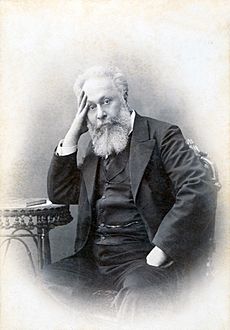

King Mirian III made Christianity the official state religion in Georgia in 324 AD.

-

The building of Svetitskhoveli Cathedral in Mtskheta, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, began in the 1020s under George I.

-

Დავით აღმაშენებელი - David Aghmashenebeli.jpg

King David the Builder, one of Georgia's greatest kings.

-

Queen Tamar and her father King George III, fresco from Vardzia.

-

Queen Tamar of Georgia, titled as "Mepe" (King).

-

Kingdom of Georgia during its Golden Age.

-

Royal armour of King Alexander III, early 1600s.

-

King Solomon I.

-

Prince Ilia Chavchavadze, leader of the Georgian national revival in the 1860s.

-

Prince Akaki Tsereteli, prominent Georgian poet and national liberation movement figure.

-

British troops marching in Batumi, Georgia in 1920. After World War I, Britain replaced German troops in Georgia.

-

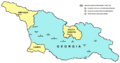

The Democratic Republic of Georgia before it was conquered by the Soviet Union.

-

Georgian SSR from 1957–1991, including Abkhazian Autonomous SSR, Adjara ASSR, and South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast.

-

Presidents Barack Obama and Mikheil Saakashvili.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Georgia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Georgia para niños