History of Hispanic and Latino Americans in the United States facts for kids

The history of Hispanic and Latino people in the United States is a long and rich story, going back more than 400 years. Hispanic people were among the first American citizens in the Southwest after the Mexican–American War. They were even the majority in some states until the 1900s.

By 1783, at the end of the American Revolutionary War, Spain controlled about half of what is now the continental United States. Spain also held Louisiana from 1763 to 1800. Spanish ships even reached Alaska in 1775. Between 1819 and 1848, the United States grew by about one-third. It gained land from Spain and Mexico, including California, Texas, and Florida.

Contents

- Early Spanish Explorers in America

- Hispanics in Early U.S. History

- Florida's Spanish Past

- Louisiana's Spanish Connection

- California's Spanish Beginnings (1530–1765)

- Spanish Control and Settlements (1765–1821)

- Mexican Era (1821–1846)

- Arizona and New Mexico

- Texas's Spanish and Mexican Eras

- United States Era (Beginning 1846)

- Recent Immigration Trends

- Hispanic Population Growth in the U.S.

- See Also

Early Spanish Explorers in America

Spanish explorers were the first Europeans to reach many parts of what is now the United States.

First Landings and Discoveries

In 1513, a Spaniard named Juan Ponce de León was the first European to land in what is now the continental United States. He landed on a beautiful shore and named it La Florida.

Within 30 years of Ponce de León's landing, the Spanish were the first Europeans to see the Appalachian Mountains, the Mississippi River, the Grand Canyon, and the Great Plains. Spanish ships sailed along the East Coast as far north as Bangor, Maine. They also sailed up the Pacific Coast to Oregon.

From 1528 to 1536, four Spanish explorers, including Estevanico, traveled all the way from Florida to the Gulf of California. This was 267 years before Lewis and Clark made their famous journey.

Major Expeditions and Settlements

In 1540, Hernando de Soto explored a huge area. His travels included Georgia, The Carolinas, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Texas, and Louisiana. In the same year, Francisco Vásquez de Coronado led 2,000 Spaniards and Mexican Indians across today's Arizona–Mexico border. Coronado went as far as central Kansas and was the first European to see the Colorado Canyon.

Many other Spanish explorers also explored the southern parts of the present-day USA. These include Lucas Vásquez de Ayllón, Pánfilo de Narváez, Sebastián Vizcaíno, Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, Gaspar de Portolà, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, Tristán de Luna y Arellano, and Juan de Oñate. Esteban Gomes explored the eastern coasts of North America up to Nova Scotia. Spaniards explored half of today's lower 48 states before the first English settlement attempt in 1585.

The Spanish created the first lasting European settlement in the continental United States at St. Augustine, Florida in 1565. Santa Fe, New Mexico was also founded before Jamestown, Virginia (1607) and Plymouth Colony (of Mayflower fame). In 1566, Pedro Menéndez established Fort San Felipe on Santa Elena, near Beaufort, South Carolina. This fort was meant to protect Spanish treasure ships traveling back to Europe.

Santa Elena became the first European capital on the American mainland. It lasted for 21 years before Spain moved its main colony to St. Augustine. Later, Spanish settlements grew in places like San Antonio, Tucson, San Diego, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. The Spanish even had a Jesuit mission in Virginia's Chesapeake Bay 37 years before Jamestown was founded.

Hispanic people have made many important contributions to American culture. These contributions have helped shape the diverse society of the U.S.

Two famous American stories have Spanish roots. Almost 80 years before John Smith's story with Pocahontas, a man named Juan Ortiz told of being saved from execution by an Indian girl. Also, Spaniards held a thanksgiving feast 56 years before the Pilgrims. They feasted near St. Augustine with Florida Indians, likely on stewed pork and beans.

Spanish Explorers in the Pacific Northwest

Spain claimed Alaska and the west coast of North America based on old agreements from 1493 and 1513. In the 1700s, Spain began to settle the northern coast of Las Californias (California). In the late 1700s, Spanish expeditions explored the coasts of Oregon, Washington, British Columbia, and Alaska.

In the 1800s, Spanish explorer Manuel Lisa, the first settler of Nebraska, traveled northwest from St. Louis, Missouri to Montana. This journey helped start the Oregon Trail. Spanish explorers moved from western Missouri to eastern Montana, and along the Yellowstone River to western and southern Montana.

Hispanics in Early U.S. History

Some Hispanic people moved to the future British colonies of North America in the early 1600s. One of these was Juan Rodriguez, who arrived in what is now New York City in 1613. He was the first non-Native American to live there. Many more came in the 1700s.

After the colonies became independent from Britain, more people from Spain, Venezuela, and Honduras moved to the United States. A well-known example is Pedro Casanave, a Spanish merchant who moved to Georgetown (now part of Washington DC) in 1785. He became the fifth mayor of Georgetown and helped lay the cornerstone of the White House in 1792.

According to the first U.S. Census of 1790, about 20,000 people of Hispanic origin lived in the former British colonies. The census estimated this based on their last names.

During the American Revolutionary War (1779-1783), Spanish troops helped the Americans fight the British. Some Spaniards living in the U.S. also joined the American forces. A notable case was Jorge Farragut, a Spanish lieutenant in the South Carolina Navy. His son, David Farragut, became famous in the American Civil War.

Florida's Spanish Past

Juan Ponce de León named Florida in 1513. He found the land on April 2, which was during the Pascua Florida (Easter season) in Spanish. From then on, the land was called "La Florida."

Over the next century, both the Spanish and French tried to settle in Florida. In 1559, Spanish Pensacola was founded, but it was abandoned and not resettled until the 1690s. French Huguenots built Fort Caroline in 1564, but Spanish forces from St. Augustine conquered it the next year.

Pedro Menéndez de Avilés founded St. Augustine in 1565. Hundreds of Spanish-Cuban soldiers and their families moved there from Cuba. St. Augustine became the capital for both British and Spanish colonies in Florida. The Spanish kept control by converting local tribes to Catholicism.

Spain's control over Florida weakened as English colonies grew to the north and French colonies to the west. The English gave guns to their Creek Indian allies, who raided Spanish-allied tribes. The English attacked St. Augustine several times, burning the city. The Spanish, in turn, encouraged enslaved people to escape from the English colonies and come to Florida. There, they were given freedom and became Catholic. They settled in Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, the first all-Black settlement in what would become the United States.

In 1763, Britain gained control of Florida through the Peace of Paris. Spain got Florida back in the Treaty of Versailles (1783) after helping defeat Britain in the American Revolutionary War. Finally, in 1819, Spain gave Florida to the United States in the Adams–Onís Treaty. In exchange, the U.S. gave up its claims to Texas. Florida became the 27th U.S. state on March 3, 1845.

Louisiana's Spanish Connection

In 1763, France gave Louisiana to Spain. This was to make up for Spain losing Florida to the British. The government of Louisiana was in New Orleans, but there were also leaders in Saint Louis, Missouri.

During Spain's time controlling Louisiana, many Spanish settlers moved there. For example, the father of explorer Manuel Lisa came from Murcia, Spain. Between 1778 and 1783, Governor Bernardo de Galvez brought groups from the Canary Islands and Málaga to Louisiana. More than 2,100 people from the Canary Islands and 500 from Málaga moved to New Orleans. In 1800, Spain gave Louisiana back to France, which then sold it to the U.S. in 1803. The families of these Spanish settlers still live there today.

California's Spanish Beginnings (1530–1765)

The first European explorers sailed along the coast of California from the early 1500s to the mid-1700s. However, no European settlements were built there at first. Spain was more focused on its main territories in Mexico, Peru, and the Philippines. Spain believed it owned all lands touching the Pacific Ocean, including California. So, they only sent a few exploring ships. California seemed to have few resources or good ports to attract many settlers.

Other European countries didn't pay much attention to California either. It wasn't until the mid-1700s that Russian and British explorers and fur traders started coming close to the area.

Early Explorers and Names

Around 1530, stories spread about a wonderful land to the northwest with gold, pearls, and gems. Hernán Cortés was interested in these stories. In 1535, Cortés claimed "Santa Cruz Island" (now the Baja California peninsula) and founded the city that would become La Paz.

In 1539, Francisco de Ulloa sailed around the peninsula and reached the mouth of the Colorado River. His journey was the first time the name "California" was used in writing. The name came from a popular adventure story about an island called "California."

João Rodrigues Cabrilho, a Portuguese sailor for Spain, was the first European to explore the California coast. In 1542, he landed at San Diego Bay and claimed what he thought was the Island of California for Spain. He sailed north, possibly as far as Pt. Reyes (north of San Francisco).

In 1602, Sebastián Vizcaíno explored California's coastline up to Monterey Bay. He made detailed maps of the coastal waters that were used for nearly 200 years. He also gave glowing reports of Monterey as a good place for ships and settlements.

Spanish Control and Settlements (1765–1821)

The first European settlements in California were built in the late 1700s. Spain was worried about Russia and Britain showing interest in the Pacific coast. So, Spain created a series of Catholic missions, along with soldiers and ranches, along California's southern and central coast. These missions were meant to show that Spain owned California.

By 1820, Spanish influence stretched from San Diego to just north of the San Francisco Bay area. It went inland about 25 to 50 miles from the missions. Outside this area, about 200,000 to 250,000 Native Americans still lived their traditional lives. The Adams–Onís Treaty in 1819 set the northern border of Spanish claims at the 42nd parallel, which is now California's northern border.

First California Colonies

Spain had missions and forts in its richer lands since 1493. But its claims to the northern parts of New Spain, except for Santa Fe, were mostly ignored for almost 250 years. It wasn't until 1765, when Russia threatened to move south from Alaska, that King Charles III of Spain decided to build settlements in Upper ("Alta") California.

Spain could only afford a small effort. Alta California was settled by Franciscan friars protected by a few soldiers in California Missions. Between 1774 and 1791, Spain sent small groups to explore and settle California.

Gaspar de Portolà's Journey

In 1768, José de Gálvez planned an expedition to settle Alta California. Gaspar de Portolà volunteered to lead it.

Portolà's land expedition arrived at San Diego on June 29, 1769. They set up the Presidio of San Diego (a fort). Portolà and his group then headed north on July 14. They quickly reached the sites of Los Angeles (August 2), Santa Monica (August 3), Santa Barbara (August 19), and San Simeon (September 13).

On October 31, Portolà's explorers were the first Europeans known to see San Francisco Bay. They returned to San Diego in 1770.

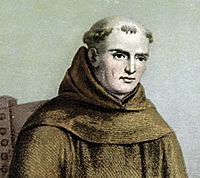

Junípero Serra and the Missions

Junípero Serra was a Franciscan priest from Spain. He founded the Alta California mission chain. After King Carlos III ordered the Jesuits out of "New Spain" in 1768, Serra became "Father Presidente."

Serra founded San Diego de Alcalá in 1769. Later that year, Serra and Governor de Portolà moved north. They reached Monterey in 1770, where Serra founded the second mission, San Carlos Borromeo.

California Missions and Ranchos

The California Missions were religious outposts built by Spanish Catholic priests. Their goal was to spread Christianity among the local Native Americans. They also helped Spain claim the area. The missions brought European animals, fruits, vegetables, and industries to California.

Most missions were small, with two priests and a few soldiers. Native Americans built these buildings under the priests' guidance. The missions were part of Spain's plan to control its territories. They needed some financial support. After the Mexican War of Independence began in 1810, this support mostly stopped.

To make travel easier, the missions were built about 30 miles apart. This was about a day's ride on horseback along the 600-mile long El Camino Real ("The Royal Highway"). Four forts, called presidios, protected the missions and other Spanish settlements.

Many mission buildings still exist today or have been rebuilt. They are seen by many as a romantic symbol of California's past. The "Mission Revival Style" is an architectural movement inspired by these missions.

The Spanish also encouraged settlement with large land grants called ranchos. Cattle and sheep were raised on these ranches. Cow hides and fat (used for candles and soap) were California's main exports until the mid-1800s. The ranch owners were like the wealthy landowners in Spain. Their workers included some Native Americans who learned Spanish and how to ride horses.

Mexican Era (1821–1846)

Big changes happened in the early 1800s. Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, ending European rule in California. The missions became less important under Mexican control, while ranching and trade grew. By the mid-1840s, more White Americans arrived. This made northern California different from southern California, where the Spanish-speaking "Californios" were in charge.

By 1846, California had fewer than 10,000 Spanish-speaking people. The "Californios" were about 800 families, mostly on large ranches. About 1,300 White Americans and 500 other Europeans lived mostly in the north. They controlled trading, while the Californios controlled ranching.

Missions Change Hands

The Mexican Congress passed a law in 1833 to take control of the California Missions. Mission San Juan Capistrano was the first to be affected. The Franciscan priests soon left the missions, taking valuable items with them. Locals then often took materials from the mission buildings for their own construction.

Other Groups Arrive

During this time, American and British trappers came to California looking for beaver. They used trails like the Siskiyou Trail and Old Spanish Trail. These trappers often arrived without Mexico's permission. They paved the way for later settlers during the California Gold Rush.

In 1840, a French explorer named Eugene Duflot de Mofras wrote that California would belong to any nation that sent a warship and 200 men. Some people worried that France wanted to take over California.

By 1846, California had about 1,500 Californio adult men (and about 6,500 women and children), mostly in the south. About 2,000 recent immigrants (mostly adult men) lived in the northern half of California.

Arizona and New Mexico

Arizona's Spanish and Mexican Periods

Most Spanish colonists left Arizona after Juan Bautista de Anza said the area wasn't rich in raw materials. However, some settlers stayed and became farmers. In the mid-1700s, Arizona pioneers tried to expand north. But the Tohono O'odham and Apache Native Americans, who raided their villages, stopped them.

In 1765, Charles III of Spain reorganized the military forts (presidios) on the northern border. The Jesuits were replaced by Franciscans at the missions. In the 1780s and 1790s, the Spanish tried to make peace with the Apache by setting up camps and giving them food. This allowed the Spanish to expand northward.

In 1821, Mexico became independent from Spain. It took control of the southwest of the present U.S., including Arizona. As missions declined, Mexico sold more land. American mountain men also started coming to the region to trap beavers.

In 1836, Texas declared independence from Mexico and claimed much of northern Mexico. When the United States took over Texas in 1846, U.S. troops moved into the disputed area. This led to the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). The U.S. won the war and forced Mexico to give up its northern half, including what would become Arizona.

New Mexico's History

Settlement in New Mexico began on July 11, 1598. The Spanish explorer Juan de Oñate came north from Mexico with 500 Spanish settlers and soldiers. They brought 7,000 animals. They founded San Juan de los Caballeros, the first Spanish settlement in New Mexico. Oñate also conquered the lands of the Pueblo people and became New Mexico's first governor.

Twelve years later, a Pueblo Indian revolt forced the settlers to leave. But they returned in 1692 when Diego de Vargas became the new governor. In 1821, New Spain (including New Mexico) gained independence from Spain. In 1824, New Mexico became part of Mexico.

Texas's Spanish and Mexican Eras

Spanish Texas

Alonso Alvarez de Pineda claimed Texas for Spain in 1519. The first Tejano settlers were 15 families from the Canary Islands who arrived in 1731. They were among the first to settle at the Presidio of San Antonio. They soon created the first local government in Texas at La Villa de San Fernando.

The Nacogdoches settlement was in North Texas. Tejanos from Nacogdoches traded with French and Anglo residents of Louisiana. They were also influenced by their culture. Another settlement was north of the Rio Grande. These southern ranchers were of Spanish origin from Tamaulipas and Northern Mexico. They identified with both Spanish and Mexican culture. In 1821, Agustin de Iturbide led Mexico to independence. Texas became part of the new independent nation without a fight.

Mexican Texas

In 1821, at the end of the Mexican War of Independence, about 4,000 Tejanos lived in what is now Texas. Many settlers from the United States moved to Texas in the 1820s. By 1830, there were 30,000 settlers, outnumbering the Tejanos six to one.

Both the Texians (American settlers) and Tejanos rebelled against the central Mexican government and the rules set by Santa Anna. Tensions led to the Texas Revolution. After the revolution, many Tejanos were upset by how they were treated by the Texians/Anglos. They were often suspected of helping Santa Anna.

United States Era (Beginning 1846)

Mexican Cession and Its Impact

The Mexican–American War began on May 13, 1846. It took almost two months for news of the war to reach California. U.S. Army and Navy units easily captured California. They quickly took control of San Francisco, Sonoma, and Sutter's Fort. Mexican General Castro and Governor Pio Pico fled from Los Angeles.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2, 1848, ended the war. The United States agreed to pay Mexico $18,250,000. Mexico officially gave California and other northern territories to the U.S. A new international border was drawn. About 10,000 Californios (people of Spanish descent) lived in California, mostly in the south. They were given full American citizenship and voting rights.

However, the California Gold Rush in the north brought over 100,000 men. They greatly outnumbered the Californios. California became a state in 1850. Even though the U.S. promised to respect Mexican American property rights, many original Californio-Mexican residents lost their land. This was due to high land values, high-interest loans, and taxes. Many lost their property and influence.

The loss of land in New Mexico created a large group of people without land. They were angry at those who took their property. Groups like Las Gorras Blancas tore down fences or burned farm buildings. In western Texas, a conflict called the San Elizario Salt War happened. The Tejano majority briefly forced the Texas Rangers to surrender. But in the end, they lost much of their power and opportunities.

In California, the settled Hispanic residents were simply overwhelmed by the large number of Anglo settlers. These settlers came first during the Gold Rush in Northern California. Later, many moved to Southern California. Many Anglos became farmers and moved onto land that had been granted to Californios by the old Mexican government, often illegally.

During the California Gold Rush, at least 25,000 Mexicans, along with thousands of Chileans, Peruvians, and other Hispanics, moved to California. Many of these Hispanics were experienced miners and found a lot of gold. However, Anglo miners often forced Hispanic miners out of their camps. They also prevented Hispanics, Irish, Chinese, and other groups from testifying in court. They set up rules similar to Jim Crow laws that affected African-Americans.

Besides California, many Mexicans moved to other parts of the Southwest (Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas) after 1852. Many Colombians, Paraguayans, Chileans, and Cubans also moved to the U.S. during the 1800s. The most numerous were the Cubans. About 100,000 Cubans moved to the U.S. (mostly Florida) during this time. From 1861-1865, many Hispanics fought in the American Civil War, on both sides.

Despite these challenges, Hispanic Americans kept their culture. They were most successful in areas where they still had some political or economic power, where they were forced to be separate, or where they made up a large part of the community.

Recent Immigration Trends

After the Spanish–American War in 1898, Spain gave Puerto Rico and Cuba to the United States in the Treaty of Paris. Cuba became independent from the U.S. in 1902. Puerto Rico became a U.S. commonwealth in 1917, so Puerto Ricans could easily move to the United States because they were U.S. citizens.

During the 1900s, many Hispanic immigrants came to the United States. They were often escaping poverty, violence, and military dictatorships in Latin America. Most Hispanics who immigrate to the U.S. are Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and Salvadorans. There are now over a million descendants of these groups in the United States. Throughout the 20th century, the Hispanic population grew quickly, both from immigration and birth rates.

Hispanic Population Growth in the U.S.

| Year | Population (millions) | %± | Percent of the U.S. population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 116,943 | — | 0.6% |

| 1860 | 155,000 | — | |

| 1870 | 200,000 | — | |

| 1880 | 393,555 | — | 0.8% |

| 1890 | 401,491 (Mexican Americans) |

+336.5% | |

| 1900 | 503,189 | +27.8% | 0.7% |

| 1910 | 797,994 | +58.6% | 0.9% |

| 1920 | 1,286,154 | +61.2% | 1.2% |

| 1930 | 1.7 | +28.6% | 1.3% |

| 1940 | 2,021,820 | +22.2% | 1.5% |

| 1950 | 3,231,409 | +59.8% | 2.1% |

| 1960 | 5,814,784 | +79.9% | 3.2% |

| 1970 | 8,920,940 | +53.4% | 4.4% |

| 1980 | 14,608,673 | +63.8% | 6.4% |

| 1990 | 22,354,059 | +53.0% | 9.0% |

| 2000 | 35,305,818 | +57.9% | 12.5% |

| 2010 | 50,477,594 | +43.0% | 16.3% |

| 2020 | 62,080,044 | +43.0% | 18.7% |

| Year | Population (millions) | %± | Percent of the U.S. population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2030 | 78.7 | +22.1% | 21.9% |

| 2040 | 94.9 | +19.2% | 25.0% |

| 2050 | 111.7 | +22.7% | 27.9% |

| 2060 | 128.8 | +22.7% | 30.6% |

See Also

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |