History of Saskatchewan facts for kids

The History of Saskatchewan tells the story of human events and activities in Saskatchewan, one of Canada's three prairie provinces. Long ago, archaeological studies show that ancient people like the Palaeo-Indian, Taltheilei, and Shield Archaic Traditions lived here. They were the first inhabitants of this land.

Later, First Nations people continued to live here, sharing their history through oral tradition. Groups like the Chipewyan, Cree, Saulteaux, Assiniboine, Atsina, and Sioux were part of this region.

The first European to visit was Henry Kelsey in 1690. Soon, other explorers and fur traders arrived, including the Hudson's Bay Company and the North West Company. Later, Clifford Sifton, a government minister, encouraged many European farmers to settle on the prairie lands near the transcontinental railway.

The borders of this area changed many times. It was first known as Rupert's Land, then became Provisional Districts of the North-West Territories, and finally, Saskatchewan became a province of Canada in 1905.

Contents

- Ancient Land and Dinosaurs

- First Peoples Before Europeans

- Early Explorers Arrive

- The Fur Trade Era

- The North-West Rebellion

- Political Boundaries Change

- Immigration and Settlement

- Population Changes

- Early 20th Century (1905–1930)

- Modern Saskatchewan (1940s–Present)

- Social and Economic Trends

- Military History

- Waterways for Travel

- Important People in Saskatchewan's History

- Art and Culture History

- Images for kids

Ancient Land and Dinosaurs

The land that is now Saskatchewan has a very long history. About 2 to 2.1 billion years ago, there were two huge landmasses, like continents, separated by an ocean. One was the "Churchill Continent" (which included parts of Manitoba and Saskatchewan), and the other was the "Superior Continent" (parts of Manitoba and Ontario).

Around 1.8 billion years ago, these two landmasses crashed into each other. This collision helped form the northern shield area and the western Rocky Mountains, making the land higher.

Later, during the Cretaceous Period (about 144 to 66 million years ago), shallow seas covered the lower lands. These seas slowly drained away, leaving behind fossils of various dinosaurs. Much later, about 2 million years ago, the ice age completely reshaped the landscape of Saskatchewan.

After these big geological changes, the continent of North America looked much like it does today, setting the stage for human history.

First Peoples Before Europeans

Archaeologists study the past by dividing time into different periods. "Prehistoric archaeology" looks at findings from before Europeans explored the area.

Ancient peoples followed different traditions. For example, the Palaeo-Indian Tradition (Agate Basin finds) dates back to around 6000 BC. The Taltheilei Tradition is from about 500 BC, and the Shield Archaic Tradition from around 4000 BC.

The Athapaskans, also known as Dene or Chipewyan First Nation, lived in the northern shield area. They were skilled caribou hunters. Their early history is documented around 1615.

Samuel Hearne was one of the first European explorers to meet the Dene people. The Algonkian or Woodland Cree lived near the treeline, while the Plains Cree lived in the open parkland. In southern Saskatchewan, buffalo hunters were mainly from the Siouan or Assiniboine (Nakota) First Nations. The Atsina or Dakota (Sioux) lived on the edges of what is now Saskatchewan.

Early Explorers Arrive

Many early explorers traveled into the West. Some important ones include:

- Louis de la Corne, Chevalier de la Corne

- Peter Fidler

- Samuel Hearne

- Anthony Henday

- Henry Kelsey

- Pierre La Vérendrye

- Peter Pond

- John Palliser

- David Thompson

- Philip Turnor

The Fur Trade Era

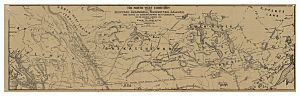

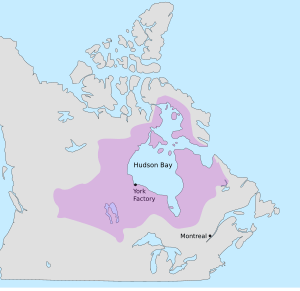

In 1670, King Charles II of England claimed the lands that drained into Hudson Bay. He gave these lands to the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC). This vast area became known as Rupert's Land. In 1774, the HBC built its first trading post, Cumberland House.

Meanwhile, French Canadian voyageurs from the North West Company traveled inland from Eastern Canada. From 1740 to about 1820, the Cree people also moved westward. They met the Haaninin and Siksika nations who already lived in the Saskatchewan river basins. The Cree continued their important role as middlemen in the North American fur trade.

European and American fur traders set up forts and trading posts. They traded with the Indigenous people. However, conflicts grew between the local Haaninin and the incoming Cree and Assiniboine. Europeans often preferred trading with the Cree and Assiniboine. This led to attacks in 1794 against both North West Company and Hudson's Bay Company forts.

Local Indigenous peoples, including the Métis, Haaninin, and Siksika, were used to hunting buffalo. Some Métis arrived from the Red River Valley in the 1840s-60s because buffalo hunting was declining there. This was a sign of what was to come further west.

When Manitoba became a province in 1870, many Métis felt their way of life was being lost. They moved into the Saskatchewan River basin, forming a new settlement. In 1872, they elected Gabriel Dumont as the first president of the council of St. Laurent. This council governed the annual buffalo hunts and other local laws.

In 1875, some Métis hunters broke the council's hunting laws. They hunted ahead of the main group. The local council fined them, but the hunters appealed to a magistrate, Lawrence Clarke. Clarke, who was also an HBC officer, sided with the hunters. He asked the North-West Mounted Police for help. Fifty officers arrived to challenge the local councils' authority. Soon after, the government of the North-West Territories moved to Battleford, and a North-West Mounted Police fort was built at Duck Lake.

In 1876, Treaty 6 was signed between the Canadian government and the local Cree peoples. While some wanted rules about buffalo hunting and land ownership, these ideas were not included in the final written treaty.

The North-West Rebellion

By 1878, the bison (buffalo) had become extinct in the region, according to Gabriel Dumont. This was a major problem for the Métis and First Nations who relied on them.

In the late 1870s and early 1880s, Métis people asked for better representation in government. The treaties gave some voice to Indigenous groups, but the territorial government was mostly controlled by European-Canadians. In April 1883, a local council decided to ask Louis Riel to return to Canada to help them.

Before Riel arrived, a petition was sent to Prime Minister Macdonald. It listed the Métis' complaints and demands, including creating the province of Saskatchewan, properly surveying their traditional river lots, and appointing Riel to the Territorial Council or Canadian Senate.

Louis Riel arrived in Saskatchewan in July 1884. He met with many councils and individuals. On March 19, 1885, he declared the establishment of the Provisional Government of Saskatchewan. On March 26, Gabriel Dumont, a leader in this government, captured Duck Lake with a small army, pushing back the North-West Mounted Police. This event marked the start of the North-West Rebellion.

Political Boundaries Change

Rupert's Land was the first western area under English control. In 1670, King Charles II of England gave the lands draining into Hudson's Bay to the Hudson's Bay Company. This area was named "Rupert's Land" after King Charles' cousin, Prince Rupert of the Rhine, who was the company's first governor.

In 1870, the North-West Territories were divided into districts. The Provisional Districts of Alberta, Assiniboia, Athabasca, and Saskatchewan were created in 1882. They were called "provisional" to show they were different from the District of Keewatin, which had more independence. Because the NWT was so large, it was divided into even more districts. In 1895, the District of Franklin, District of Ungava, and the District of Mackenzie were formed, all part of the NWT.

Immigration and Settlement

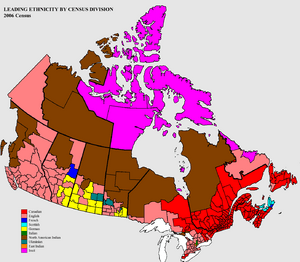

Settlement patterns were closely linked to transportation, especially railways, and good soil. Different ethnic groups often settled together. This helped them build support networks for their religion, language, customs, and finding marriage partners.

Travel Routes and New Towns

When railway surveyors first planned routes, they considered following the early telegraph line. However, the route changed. Traveling from Winnipeg to Calgary was easier through the southern prairies. This southern railway route passed through a village called Pile O' Bones in 1882. By 1903, many settlers arrived by railway, and Pile O' Bones grew into a city known as Regina. In 1905, when Saskatchewan became a province, Regina was named the capital city.

Immigration was heavily promoted by Clifford Sifton, the Minister of the Interior in charge of immigration from 1896 to 1905. He helped create Canada's homestead act, the Dominion Lands Act, in 1872. The railway brought life to settlements, which quickly grew into villages and towns. Many small communities sprang up about 10–12 miles apart, a distance easily traveled by horse and cart in a day.

Encouraging Settlement

The federal government, the Canadian Pacific Railway, the Hudson's Bay Company, and other land companies encouraged immigration. A key event was the decision to offer 160 acres of farmland for free to any man over 18 (or a woman head of family) who settled there. This was similar to the American Homestead Law.

Big advertising campaigns promoted prairie living. Leaflets described Canada as a "garden of Eden" and downplayed the need for farming experience. Ads in The Nor'-West Farmer suggested western land had plenty of water, wood, and cheap fuel. The reality was much harder, especially for early arrivals who lived in sod houses. However, money from eastern Canada flowed in, and by 1913, long-term loans to Saskatchewan farmers reached $65 million.

Diverse Settlers

The main groups of settlers were British from eastern Canada and Britain. They made up about 50% of the population in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They played a big role in setting up the basic systems of society, economy, and government.

By 1930, there were 19 major groups of settlers who formed "bloc settlements" in Saskatchewan, mostly in the north-central region. These included French, German Catholic, Mennonite, Hutterite, Ukrainian-Polish, Russian Doukhobor, and Scandinavian communities. They varied greatly in size.

For example, in 1899, Interior Minister Clifford Sifton set up bloc colonies for 7,400 Doukhobor settlers from Russia. Peter Verigin arrived in 1902 and became their leader.

The Barr Colonists, another group, traveled north in 1903 and settled in Brittania, now known as Lloydminster, Saskatchewan.

German Settlers

Many German settlers came from Russia, and after 1914, from German-American settlements in North and South Dakota. They often came as part of family chains, where early immigrants found good locations and sent for others. They formed close-knit German-speaking communities around their Catholic or Lutheran churches, keeping old customs alive. They were farmers who grew wheat.

These German communities often ran their own schools to keep their religious faith strong. These schools usually taught German for only an hour a week but had extensive religious lessons. By 1910, most German Catholic children attended schools taught entirely in English.

Ukrainian Settlers

In 1911, 22,300 Ukrainians lived in Saskatchewan, and this number grew to 28,100 by 1921. Only Manitoba had more Ukrainian residents.

Ukrainians, sometimes called "Ruthenians" back then, started arriving in large numbers in the 1890s. They came as farmers and actively built churches. Their requests for public schools that taught in Ukrainian were often turned down by local officials.

During World War One, many Ukrainian men were not Canadian citizens but subjects of Austria-Hungary, an enemy nation. About 5,000 men were held in camps, mostly those caught trying to cross the border into the U.S. They were assigned to work on public projects and railways.

Ukrainians were divided among different Catholic and Orthodox churches. The "Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada" was created in 1918 to protect the interests of the people against discrimination. Since World War Two, Ukrainians have largely blended into Canadian culture.

Family Life on the Prairies

Gender roles were very clear. Men were mainly responsible for breaking the land, planting and harvesting, building the house, and handling money. At first, many single men or husbands whose wives were still back east struggled. They soon realized they needed a wife.

In 1901, there were 19,200 families, but this number jumped to 150,300 families just 15 years later. Wives were crucial to settling the prairie region. Their hard work, skills, and ability to adapt to the tough environment were key to success. They cooked, mended clothes, raised children, cleaned, tended gardens, helped during harvest time, and nursed everyone back to health. Even though women's contributions were often overlooked, their flexibility in doing both productive and household work was vital for family farms to survive and for the wheat economy to thrive.

Population Changes

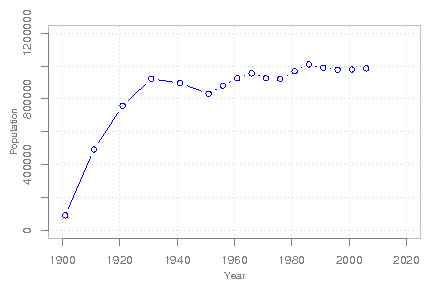

When Saskatchewan became a province in 1905, many believed it would become Canada's most powerful province. Saskatchewan started a big program to build the province based on its Anglo-Canadian culture and wheat production for export. The population grew five times, from 91,000 in 1901 to 492,000 in 1911. This was thanks to many farmers immigrating from the U.S., Germany, and Scandinavia. Efforts were made to help newcomers adopt British Canadian culture and values.

The population reached 758,000 in 1921 and peaked at 922,000 in 1931. It lost people during the Great Depression and war years, dropping to 830,000 in 1951. Then, it slowly grew back, staying around one million since 1986.

In 2006, the largest ethnic groups were German (30.0%), English (26.5%), Scottish (19.2%), Irish (15.3%), Ukrainian (13.6%), French (12.4%), First Nations (12.1%), and Norwegian (7.2%).

Early 20th Century (1905–1930)

Government and Economy

In 1905, the provisional districts of Assiniboia, Saskatchewan, and Athabaska from the North-West Territories joined to form the province of Saskatchewan. Its borders were set: the 4th Meridian to the west, the 49th parallel to the south (the US-Canada border), the North-West Territories-Saskatchewan boundary to the north, and near the 2nd Meridian on the eastern border with Manitoba.

The early government created local improvement districts (later called rural municipalities). Their first job was to protect against prairie fires and build roads and bridges. As homesteads were set up and farming methods improved, communities slowly grew. With more money, rural municipalities could build schools, churches, cemeteries, and provide health care for their residents.

The province's long-term success depended on the world price of wheat. Prices steadily rose from the 1880s to 1920, then dropped sharply. Wheat production increased with new types of wheat, like the "Marquis" strain, which grew faster and yielded more. Canada's wheat output soared from 8 million bushels in 1896 to 151 million by 1921.

In the 1905 provincial elections, Liberals won most of the seats. The Saskatchewan government bought out Bell Telephone Company in 1909. The government owned the long-distance lines, and local service was handled by small companies at the municipal level. Premier Thomas Walter Scott preferred government support over full ownership. He believed things worked better if citizens had a stake in running them. He set up the Saskatchewan Cooperative Elevator Company in 1911.

World War I and Social Change

When World War I began in 1914, Saskatchewan responded with great patriotism and an economic boom. The price of wheat tripled, and the amount of land planted doubled. The wartime spirit encouraged social reform movements that had started before the war. Saskatchewan gave women the right to vote in 1916. By the end of 1916, a vote passed to stop the sale of alcohol.

Patriotism also led to a demand for everyone in the province to speak English. The war brought out fears about different ethnic groups and a strong desire for a Canadian identity.

After the War (1919–1939)

The economy crashed after the war, leading to an angry protest movement among farmers. Prairie farmers felt they were victims of powerful companies—grain companies, banks, and railways—all based in Toronto and Montreal. They blamed high tariffs (taxes on imported goods) that protected manufacturers but hurt farmers.

During the war, farmers felt betrayed. The federal government first promised to excuse their sons from military service, then canceled the exemption. It put a limit on wheat prices when they were high but removed the limit when they were low. This frustration led to the formation of the Progressive Party.

To control wheat prices, 46,000 farmers joined together in 1923–24 to create the "Saskatchewan Co-operative Wheat Producers"—the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool. This group bought almost all the wheat and stored it to get the best price. The pool faced financial trouble in 1931, and the federal government had to cover its losses. The co-op continued as a network of elevators owned by farmers.

The Roaring Twenties brought ethnic tensions and great prosperity. The illegal alcohol trade, including smuggling whisky, used caves around Cypress Hills and the Soo Line Railroad that ended in Moose Jaw, known as "Sin City of the North."

The Saskatchewan Grain Growers' Association worked with the provincial Liberals, keeping them in power until 1929. The late 1920s were good years as wheat prices recovered. By 1927, Saskatchewan was first among the provinces in producing wheat, oats, rye, and flax. Most importantly, it ranked first in wealth per person. With a population of 922,000 in 1931, it was the third largest province.

The Great Depression hit the prairies hard, especially with the drought of the Dirty Thirties. The world market for wheat collapsed, and income per person dropped by 75%. Thousands left their family farms because the land could no longer support them. Relief spending in the province in 1937 was over $40 million, much more than the entire provincial budget of $23 million in 1939. The government added a new 2% sales tax to cover payments given to teachers instead of salaries.

In 1930, Saskatoon started "work for wages" programs to give unemployed people manual jobs. These projects kept unemployment manageable at first. By 1932, the depression worsened. The federal and provincial governments, short on money, had to stop expensive public works. They switched to cheaper direct relief, giving out cash and food baskets. This led to protests in cities, including the Estevan Riot and the Regina Riot.

Finally, prosperity returned after 1939 as farm prices rose, and Saskatchewan joined the war effort.

Modern Saskatchewan (1940s–Present)

Social Changes (1940s–1950s)

As late as 1940, Saskatchewan was mostly rural, with many small villages and towns. Two-thirds of the people lived on farms. Only a small portion lived in towns or cities. The cities were mainly trading centers serving rural areas. Railroads, wholesale trade, and retail trade employed most urban workers.

After 1945, mechanization changed Saskatchewan. Combines and machine farming became common. Farms grew larger, and more people moved to urban centers. One-room schoolhouses closed, replaced by larger, more modern schools in towns. These changes led to the contemporary society of Saskatchewan.

Tommy Douglas and the CCF

A new political movement, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), emerged. Its 1933 plan aimed to create a "Co-operative Commonwealth" in Canada. Tommy Douglas (1904–86), a Baptist minister, led the CCF to power in 1944 and stayed in power until 1961. Douglas led the first socialist government elected in Canada. He is known as the father of socialized medicine and for bringing democratic socialism into mainstream Canadian politics.

The Saskatchewan CCF won in June 1944 with a platform that included home ownership, debt reduction, better old age pensions, public medical, dental, and hospital services, equal education, and collective bargaining. The CCF, while socialist in its ideas, did not nationalize all banks or industries. It aimed for a mixed economy with public, private, and cooperative parts, and a strong role for private ownership, but with new controls. For example, in its first term, the CCF passed a farm security act to stop banks from taking over family farms.

The CCF government also introduced the most pro-labor trade union act in North America. Saskatchewan became the first province to allow civil servants to form unions (1944). It was also the first to have a bill of rights banning discrimination based on race, color, or religion (1947), the first to have compulsory government automobile insurance (1946), and the first to start a hospital insurance plan (1947).

The CCF government also set up eleven small Crown corporations, including power and telephone companies, bus and airline companies, and ventures into mining and manufacturing. By 1949, most of the non-utility corporations were not making a profit and stopped operating.

Prosperity returned after 1945, and the population slowly increased. More dramatically, people moved from farms to towns and cities as farming became more mechanized. Increased production of oil, gas, and uranium, and the start of a potash industry, helped the economy become more diverse than just wheat.

Policies for Indigenous Peoples

Douglas brought First Nations delegates together in 1946 to form a single organization to represent their interests. Three existing groups merged into the Union of Saskatchewan Indians, which later became the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations. Douglas's team studied the challenges facing the First Nation population. Today, the FSIN is a strong organization for policy-making and program delivery in Canada.

The CCF also encouraged Indigenous people in the north to move from their semi-nomadic lifestyles to urban settings. New villages were established, but local people were often not included in the planning. Despite resistance, many incentives and measures led almost all northerners to move to permanent settlements.

Universal Health Care

In 1959, Douglas promised universal medical care insurance. This plan would be based on pre-payment, quality service, and government administration, and be acceptable to both doctors and patients. The 1960 election was fought over this issue. Doctors campaigned against it, but the CCF won.

The Saskatchewan Medical Care Insurance Bill became law in November 1961. Doctors announced they would refuse to participate, saying it would bring too much control and interfere with the doctor-patient relationship. The doctors even went on strike for a few weeks in July 1962. However, they returned when new laws allowed them to practice outside the system. Eventually, the Saskatchewan plan became so popular that in 1968, the federal government expanded it nationwide.

Douglas later became the leader of the federal New Democratic Party.

In the 1964 Saskatchewan provincial election, the Liberal party, led by Ross Thatcher, won, ending 20 years of CCF government. The Liberals promised more private businesses and industrial development, along with tax cuts.

Recent History (Since 1971)

Thatcher and his Liberals were re-elected in 1967 but were defeated by Allan E. Blakeney and the NDP in 1971. The NDP was re-elected in 1975.

Blakeney's government focused on state-led economic involvement. Farmers were a high priority as globalization changed agriculture, making traditional family farms weaker. The NDP promised a "revitalized rural Saskatchewan" and introduced programs to stabilize crop prices, keep transportation links, and modernize rural life.

The NDP decided to nationalize the potash industry in 1976–78 by buying out 45% of the mining interests. The government created a Crown corporation in the potash industry to diversify the province's farming economy. By 1979, the Crown Investments Corporation, which held the crown corporations, had assets of $3.5 billion.

Blakeney also created a state-owned oil and gas company (SaskOil) for oil exploration and production. The private oil industry had mostly left Saskatchewan after the NDP put high royalty rates in place in the early 1970s. Blakeney disagreed with Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau's policies to centralize control of natural resources in Ottawa. He joined Alberta Premier Peter Lougheed in fighting for provincial rights over minerals, oil, and gas.

Nationalization was the main issue in the 1978 elections. The NDP held its ground, but the Liberals lost many seats, and the Progressive Conservative party grew. Prosperity was good, with high prices for wheat, oil, and uranium. The NDP used resource revenues to build on the social welfare programs started by the CCF. They introduced a guaranteed income for senior citizens, a family income plan for the working poor, a children's dental service, and a prescription drug plan.

Since 1982

In 1982, voters went to the polls as the economy slowed down, with falling prices for wheat, oil, potash, and uranium. The NDP was largely defeated after twelve years in power. The Progressive Conservative Party won most of the seats. The new premier was 37-year-old economist Grant Devine. He won with a simple message: people should share in the province's wealth instead of seeing it go to the 24 Crown corporations. The new government ended the 20% tax on gasoline and lowered interest rates on mortgages. They were re-elected in 1986 and began selling off crown corporations. The government said the companies would run more profitably as private businesses. The opposition NDP warned that the sales would mean losing control over the province's key economic areas.

After taking over with balanced books in 1982, the Progressive Conservatives spent freely on voter-friendly programs, including tax rebates and mortgage subsidies. They also invested millions in several money-losing large projects. The provincial debt grew significantly. The Progressive Conservatives lost many rural voters after supporting the unpopular U.S.-Canada Free Trade Agreement in 1989. As a result, the NDP was returned to power in 1991.

Scandals involving top officials hurt the Progressive Conservative party, which stopped operating in 1997. Conservative voters moved to the new Saskatchewan Party at the provincial level. The NDP won re-election in 1995, 1999, and (with the Liberals) again in 2003. Lorne Calvert, an ordained minister, served as NDP premier from 2001 to 2007.

Brad Wall became premier when his centre-right Saskatchewan Party took over from the NDP after a big victory in the November 2007 election. His party's success grew after four years of strong economic management, nearly wiping out the NDP in the 2011 election.

Social and Economic Trends

In 2005, two-thirds of Saskatchewan's population lived in urban areas. The province had a diverse economy, and citizens enjoyed a rich cultural life. The economic future, based on high-priced oil and wheat, looked promising. Saskatchewan is a major supplier of oil to the U.S. The province has significant reserves of conventional oil and potential oil sands.

Rural towns have changed a lot. In 1900, there were many small grain delivery points. Over the first thirty years of the 20th century, these expanded. By 2000, population and businesses were more concentrated in urban areas. Mechanization, especially the quick change from horses to tractors after 1945, meant one family could farm a much larger area. So, some farmers bought out their neighbors, who then moved to town.

The rural economy became much more diverse than just farming. Service jobs in education and medicine became important, as did small factories. Better highways, along with cell phones and internet coverage, encouraged people to gather in fewer, larger centers. These centers attracted customers and clients from a wide area. Most rural communities declined in the second half of the 20th century. However, some grew, expanded their economy, and became employment centers for their own and surrounding populations.

The Wheat Pool continues to operate as Viterra. In 2007, it took over Agricore United. With rising wheat prices, Viterra's revenues grew significantly.

Military History

Saskatchewan's Military history includes early conflicts between different First Nations. Before European settlement, many battles were fought between the Blackfoot, Atsina, Cree, Assiniboine, Saulteaux, Sioux, and Dene. Many place names, like the Battle River, recall these early conflicts. The Blackfoot Confederacy and Atsina were pushed out of Saskatchewan after decades of fighting with the Cree, Saulteaux, and Assiniboine. In the boreal forest, conflicts continued between the Woods Cree and Dene until the late 19th century.

The creation of the Métis added a new dimension to conflicts in what is now Saskatchewan. Besides violence related to the fur trade between the North West Company and Hudson's Bay Company (which ended in 1821), the Métis fought battles with the Sioux and Gros Ventre across the plains. The last battles fought in Saskatchewan, and the last battles fought in what is now Canada, happened in 1885 during the North-West Rebellion. Although small by global standards, this short war deeply affected Canadian French-English relations and was a defining moment for the West and the Métis.

Since Saskatchewan became a province in 1905, its people have contributed greatly to wars fought by Canada. Saskatchewan Regiments were formed for the second Boer War, World War I, World War II, and Korean War. Many Saskatchewan citizens have also served in United Nations peacekeeping operations and in the Afghan War.

Current Saskatchewan regiments in the Primary Reserve of the Canadian Forces include the North Saskatchewan Regiment and the Royal Regina Rifles.

Waterways for Travel

Travel by boat and canoe along the waterways of what is now Saskatchewan was historically very important. During the early fur trading era (17th to 19th centuries), waterways were the main way to travel inland in North America, as there were no roads or railways. First Nations and French fur traders from the East used birch bark canoes. English fur traders from the Hudson's Bay Company traveled by York boat.

In the late 19th century, steamboats were used to transport immigrants and goods along the Saskatchewan River. This continued only until 1896 because winter ice and shallow sand bars made this type of travel difficult. A notable event during the steamboat era was their impact on the North-West Rebellion.

Since then, the main use of boat travel is by the 13 seasonal ferries that are still operating and began in Saskatchewan in the late 19th century. Barges are used to transport freight on the larger northern lakes, Wollaston and Athabasca, for the northern mining industry.

Important People in Saskatchewan's History

This section highlights some key individuals who helped shape Saskatchewan.

- Louis Riel (1844–1885): A Canadian politician, founder of Manitoba, and leader of the Métis people.

- Honourable Sir Frederick William Alpin Gordon Haultain (1857–1942): Chief Justice of Saskatchewan and Commissioner of Education, who developed the early school system.

- The Right Reverend George Lloyd (1861–?): Bishop of the Diocese of Saskatchewan, leader of the British Barr Colony, and founder of Emmanuel College, Saskatoon.

- Edgar Dewdney: Moved the North-West Territories capital from Battleford to Regina.

- Reverend James Nisbet (1823–1874): Settled in the Prince Albert, Saskatchewan area and founded First Presbyterian Church (1872), which offered English and Cree Sunday School services.

- William Richard Motherwell: Saskatchewan's first minister of agriculture and later federal minister of agriculture.

- Thomas Clement Douglas (1904–1986): Leader of the Saskatchewan Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) and the seventh Premier of Saskatchewan (1944–1961). He led the first socialist government in North America and introduced universal public medicare to Canada.

- John George Diefenbaker (1895–1979): The 13th Prime Minister of Canada (1957–1963).

Art and Culture History

The Art history of Saskatchewan is rich and varied, reflecting the changes and social context of the province. Petroglyphs (rock carvings) are the earliest art forms found at archaeological sites.

As early as the 17th century, explorers drew and painted the early North West lands. Some of the earliest artists include Frederick Verner, W.G.R. Hind, Peter Rindisbacher, Edward Roper, and Paul Kane. Later artists include William Kurelek, C. W. Jefferys, Robert Hurley, and Dorothy Knowles. Writers like Margaret Laurence, W.O. Mitchell, and Nellie McClung captured the prairie spirit in their words.

In the 1920s, the Group of Seven formed, a group of Canadian landscape painters. Augustus Kenderdine, a landscape painter, started art instruction at Murray Point on Emma Lake. The way the grasslands were shown in art changed over time, from romantic adventures of First Nations and buffalo to highlighting the building of a nation, and then to the realism of the settlement experience.

- Paul Kane (1810–1871): An Irish-Canadian painter famous for his paintings of First Nations peoples in the Canadian West.

- Henry Youle Hind (1823–1908): A Canadian geologist and explorer who documented his travels in images and writings.

- Count Imhoff (1865–1939): Painted beautiful religious murals in churches across Saskatchewan.

- Joni Mitchell (born 1943): A famous Canadian musician, songwriter, and painter.

- W.O. Mitchell (1914–1998): Born in Weyburn, Saskatchewan, he was an author of novels, short stories, and plays, like Who Has Seen The Wind.

- Joe Fafard (born 1942): A Canadian sculptor who also taught sculpture at the University of Saskatchewan.

Images for kids

de:Saskatchewan#Geschichte

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |