Indigenous peoples of California facts for kids

The Indigenous peoples of California, also called Native Californians, are the many different groups of people who have lived in the area now known as California for thousands of years. They were here long before Europeans arrived. Today, there are 109 tribes officially recognized by the government in California. Many more tribes are working to get this recognition. California has the second-largest Native American population in the United States.

For thousands of years, most tribes used special methods like forest gardening and controlled burning. This helped them grow food and medicinal plants, keeping the environment healthy. European settlers started exploring their lands in the late 1700s. Spanish soldiers and missionaries built missions, which led to many deaths and the loss of Native cultures.

Later, after California became a state, a terrible time known as the California genocide happened. This was a state-supported effort against Native people. The Native population reached its lowest point in the early 1900s. Children were forced into Indian boarding schools to make them adopt white society's ways. Today, Native Californian peoples continue to fight for their cultures, lands, and sacred places. They also work to protect their right to live freely.

In recent years, some California tribes have started bringing their languages back to life. The Land Back movement is also growing, aiming to return land to Native tribes. California is also beginning to understand how Native peoples' knowledge of the environment can help improve ecosystems and prevent wildfires.

Contents

Who Are Indigenous Californians?

The traditional lands of many tribes don't always match California's current borders. Some tribes near the Nevada border are seen as Great Basin tribes. Others near the Oregon border are called Plateau tribes. The Kumeyaay nation, for example, lives on both sides of the Mexico-United States border.

A Look at History

Ancient Times

People have lived in California for at least 19,000 years. Scientists have found ancient sites showing human life from 12,000 to 7,000 years ago. These include places like Borax Lake and the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. The oldest human remains found, called the Arlington Springs Man, are 10,000 years old.

Before Europeans arrived, there were about 500 different Native groups or "sub-tribes" in California. Each group had between 50 and 500 members. California had the largest Native American population north of Mexico. This was because of the mild weather and easy access to food. About one-third of all Native Americans in the United States lived in California.

Early Native Californians were hunter-gatherers. They collected seeds, hunted animals, and gathered plants. Around 9,000 BCE, seed collection became very common. Over time, different groups developed unique ways of life that fit their local environments. Many traits of today's tribes were already in place by 500 BCE.

Native people used advanced methods to care for the land. They practiced forest gardening in forests, grasslands, and wetlands. This helped them grow food and medicine plants. They also used controlled fires to manage the land. This prevented huge wildfires and helped new plants grow. By burning old brush, they created fresh shoots that attracted animals for hunting. This was a form of permaculture, a way of farming that works with nature.

First Contact with Europeans

Different tribes met European explorers and settlers at different times. Tribes along the southern and central coasts met Europeans in the mid-1500s. Tribes like the Quechan in southeast California first met Spanish explorers in the 1760s and 1770s. Tribes on the northwest coast, such as the Miwok and Yurok, had contact with Russian explorers in the late 1700s. Some tribes in remote inland areas didn't meet non-Natives until the mid-1800s.

Late 1700s: Missions and Decline

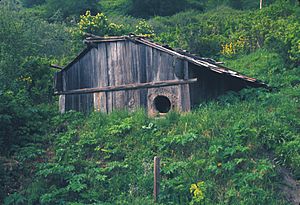

When the first Spanish Mission was built in 1769, California's Native population was estimated to be around 340,000 people. Native Californians were very diverse, speaking at least 78 different languages from ten language families. They lived in villages of 400-500 small groups.

The Spanish began their long stay in California in 1769 by building Mission San Diego de Alcalá in San Diego. They built 20 more missions, mostly in the late 1700s. Between 1769 and 1832, records show 87,787 baptisms and 63,789 deaths at the missions. This huge drop in population was due to new diseases spreading quickly in crowded mission conditions. Overwork and poor nutrition also played a part.

The missions also brought European plants and cattle grazing that changed California's landscape. This altered Native peoples' connection to the land and the plants and animals important to their lives. The missions also tried to erase Native culture by forcing people to convert to Christianity. They banned many cultural practices, often using violence.

1800s: A Time of Great Loss

The Native population of California dropped by 90% during the 1800s. It went from over 200,000 people to about 15,000. Most of this decline happened in the second half of the century, after Americans took control. By 1870, the population was 30,000, and by the end of the century, it was 16,000.

This massive population loss was caused by diseases like a malaria outbreak in 1833. It was also due to state-supported killings that increased under American rule.

Russian Explorers (1812–1841)

In the early 1800s, Russian explorers visited California. Baron Ferdinand von Wrangell visited in 1818, 1833, and 1835. He met Native people north of San Francisco Bay. He noted that Native women seemed stronger than men because they did more physical work. He thought California Indians were independent, creative, and had a unique sense of beauty.

Another Russian scientist, Ilya Voznesensky, visited from 1840 to 1841. He collected materials for the Imperial Academy of Sciences. He described the local tribes he met as "untamed Indian tribes... who roam like animals." He noted they were protected by thick plants, which kept them from being enslaved by the Spanish.

Mexican Rule Changes (1833–1848)

After Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, its government made changes. In 1833, a law was passed to "secularize" the missions. This meant the missions no longer had religious control over Native people in California. This law was passed because some believed the missions stopped Native people from owning their own land.

However, the Mexican government did not return the land to the tribes. Instead, they gave large land grants, called ranchos, to settlers of European descent. This gave Native people a chance to leave the missions, but many were left without land. They were then forced to work for wages on the new ranchos. Only a few Native people who had adopted Spanish ways and Christianity were able to get land grants.

American Settlers Arrive (1848–)

After the United States won the Mexican–American War in 1848, Peter Hardeman Burnett became California's first governor. American settlers took control of California. The U.S. government honored some Mexican land grants but did not recognize Native peoples' original land rights.

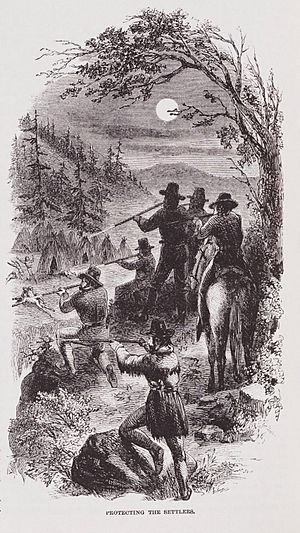

The U.S. government then started a policy to remove Native people from California. In 1851, Governor Burnett said that a "war of extermination" would continue until the Native race became extinct. He believed this was necessary to protect white settlers' property.

California formed groups of armed citizens called militias. These groups were paid to kill Native people. Between 1851 and 1852, California spent about $1 million on these militias. The U.S. government also helped pay for these efforts to eliminate Native people.

Gold Rush and Forced Labor (1848–1855)

Most of inland California, including the deserts and the Central Valley, belonged to Native people until the U.S. took control. In 1848, gold was discovered at Sutter's Mill. This led to a huge rush of American settlers into Native lands. The California Gold Rush involved many massacres and fights between settlers and Native people. This period, from about 1846 to 1873, is known as the California genocide.

The Gold Rush had a terrible impact on Native people and the environment. About 100,000 Native people died in the first two years of the Gold Rush alone. Settlers took land for their camps and farms, which destroyed Native food sources. Mining waste also polluted rivers, killing fish and destroying habitats. Settlers saw Native people as obstacles to finding gold.

Forced labor was also common during the Gold Rush. A law passed in 1850, called the "Act for the Government and Protection of Indians," allowed this. This law made it legal for people to get Native children for "indenture," which was like slavery. Raids on Native villages were common. Adults and children were threatened if they refused to work. Even though this was technically illegal, law enforcement rarely stopped kidnappings. Native people were "bought" for as little as 35 dollars at what were essentially slave auctions.

Los Angeles was a main place for these auctions. A city law in 1850 allowed prisoners to be "auctioned off to the highest bidder for private service." This practice continued weekly for nearly 20 years, until there were almost no Native Californians left to sell.

Unkept Promises (1851–1852)

In 1851, the U.S. Senate sent officials to make treaties with Native Californians. Leaders from across the state signed 18 treaties. These agreements promised 7.5 million acres of land (about one-seventh of California) to Native people. This was meant to protect their future as settlers moved in. However, American settlers in California were angry, thinking Native people were getting too much land. The U.S. government sided with the settlers. They put the treaties aside without telling the Native signers. These treaties were never officially approved.

California Genocide (1846–1873)

The California genocide continued after the Gold Rush. By the late 1850s, American militias were attacking Native lands in northern and mountainous areas. These areas had avoided some earlier violence because they were more remote. Near the end of this period, in 1873, the final stage of the Modoc War began. Modoc fighters, led by Kintpuash (also known as Captain Jack), killed General Canby during a peace meeting. However, between 1851 and 1872, the Modoc population dropped by 75% to 88% due to attacks by white settlers.

There is evidence that the first massacre of the Modocs by non-Natives happened as early as 1840. A chief from the Achomawi tribe said that trappers invited Modocs to a feast near Tule lake. When they sat down to eat, a cannon was fired, killing many Native people. Captain Jack's father was one of the survivors. After this, the Modocs strongly resisted outsiders. Also, when the Applegate Trail was built through Modoc territory in 1846, migrants and their animals damaged the environment that the Modoc depended on for survival.

1900s: Forced Changes

By 1900, only about 16,000 Native people had survived the harsh policies of the 1800s. Those who remained continued to face U.S. policies that tried to erase their cultures throughout the 20th century. Many Native groups were wrongly declared "extinct" during this time.

Native Removal in California (1903)

The U.S. policy of forcing Native peoples off their lands, known as Indian removal, began much earlier in the United States. But it was still happening in Southern California as late as 1903. The last forced removal of Native people in U.S. history was the Cupeño trail of tears. The Cupeño people were forced from their homeland by white settlers who wanted their land, now known as Warner Springs. The Cupeño were made to move 75 miles from their village of Cupa to Pala, California.

Indian Boarding Schools (1892–1935)

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the government tried to force Native peoples to give up their culture and become like white society. In California, the government set up reservation day schools and American Indian boarding schools. Three of the 25 off-reservation boarding schools were in California.

When new students arrived, their hair was usually cut, and they were bathed in kerosene. These schools often had poor air circulation, bad food, and diseases. Most parents did not want their children raised as white. Students were forced to wear European clothes and haircuts, given European names, and strictly forbidden to speak their Native languages.

By 1926, 83% of all Native American children attended boarding schools. Native people saw these schools as a way to destroy their culture. They demanded the right for their children to go to public schools. In 1935, the rules that stopped Native people from attending public schools were removed.

It wasn't until 1978 that Native people won the legal right to prevent their families from being separated. This separation was a key part of how children were taken to boarding schools. Often, parents didn't know, or children were taken under false claims that they were "unsupervised." Sometimes, families were threatened.

Unratified Treaties: A Small Payment (1944–1946)

Since the 1920s, Native activist groups demanded that the government keep the promises of the 18 treaties from 1851–1852. These treaties were never officially approved. In 1944 and 1946, Native peoples asked for money to make up for the lands affected by these treaties and Mexican land grants. They won $17.5 million and $46 million, but the land itself was not returned.

Religious Freedom Act (1978–)

The American Indian Religious Freedom Act was passed in 1978. It gave Native people some rights to practice their religions. However, in reality, this didn't fully protect their religious connection to natural sites or ecosystems. American law often sees religion as separate from land, which is different from Native beliefs. So, while religious freedom was protected in theory, sacred sites and practices were not always protected.

For example, the National Park Service has a "no-gathering" rule for cultural or religious purposes. The United States Forest Service (USFS) requires special permits and fees, which limits Native religious freedom. A plan in 1995 to allow some gathering for religious purposes did not pass. Also, pesticides used in forests, like 11,000 pounds of hexazinone dropped on Stanislaus National Forest in 1996, harmed plants and wildlife important to Native culture and religion.

2000s: A New Era

California has the largest Native American population of any state. About 723,000 people identify as "American Indian or Alaska Native." This is 14% of the total Native American population in the U.S. This population grew by 15% between 2000 and 2010. Over 50,000 Indigenous people live in Los Angeles alone.

Today, there are over 100 federally recognized Native groups or tribes in California. Federal recognition gives tribes access to services and funding from the government.

Recognizing the Genocide (2019)

For over a century, the California genocide was not acknowledged by non-Native people in California. In the 2010s, many politicians, academics, and schools denied or downplayed it. This was partly because people who benefited from these past policies didn't want to admit what happened. They often dismissed or distorted the history.

In 2019, California Governor Gavin Newsom formally apologized to Native people. He also created a Truth and Healing Council to report on the state's history with its Indigenous people. Newsom stated, "Genocide. No other way to describe it, and that’s the way it needs to be described in the history books." This was a big step in acknowledging the California genocide.

Language Reawakening

After a long decline, some Indigenous languages are being brought back to life. This decline happened because Native languages were punished in Indian boarding schools and other ways. Language revitalization is gaining strength among several tribes in California. There are still challenges, like healing from past traumas, getting enough money, and finding old records.

Some languages having success include Chumash, Kumeyaay, Tolowa Dee-ni', Yurok, and Hoopa. Cheryl Tuttle, a Wailaki teacher, said that language revitalization is important for both the speakers and the land. She explained that the land "needs to hear those healing songs and prayers again."

Protecting Sacred Sites

In 1990, federally recognized tribes gained some rights to their ancestors' remains through the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. A similar California law requires state agencies and museums to return human remains and cultural items to the proper tribes.

However, these laws don't stop building projects on Native burial grounds. They only require a temporary discussion and return of remains found. Tribes in cities or areas with lots of development, like the Tongva in Los Angeles and the Ohlone in the San Francisco Bay Area, struggle to protect burial grounds and village sites. These sites are often disturbed by new homes and businesses, which has been a problem for Native people since Europeans arrived.

For example, in 1982, a California court case allowed developers to destroy a Miwok burial ground in Stockton, California. Over 600 burial remains were removed for a housing project. The Miwok had no power to stop it because Native American burial grounds were not legally considered cemeteries.

The West Berkeley Shellmound, a paved ancient site, is still threatened by housing developments. Many Tongva village sites and burial grounds in the Los Angeles area continue to be disturbed by new buildings. For instance, 400 burials were dug up at Guashna for a development in Playa Vista in 2004. The Acjachemen sacred village site of Putiidhem was buried under a high school in 2003, despite protests.

The Land Back Movement

The Land Back movement in California is gaining attention. A major event was the return of Tuluwat Island to the Wiyot tribe. This island was the site of a terrible massacre in 1860. The tribe began buying parts of the island in 2000. In 2015, the Eureka City Council voted to return the island. This was possibly the first time a U.S. city returned land to a Native tribe without conditions. The official transfer happened in 2019.

Tribes not recognized by the federal government often don't have their own land. This makes it harder for them to keep their tribal identity visible. Land Back movements aim to return land to these tribes. Examples include the Sogorea Te Land Trust and the Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy. They created the Shuumi Land Tax and the kuuyam nahwá’a (guest exchange). These are ways for people living on traditional Native lands to contribute. In 2021, the Alameda City Council became the first city to pay the Shuumi Tax.

Daily Life and Culture

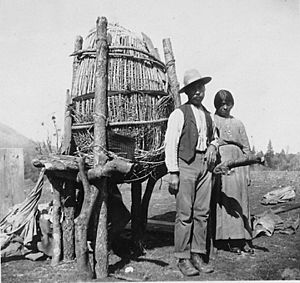

Basket Weaving

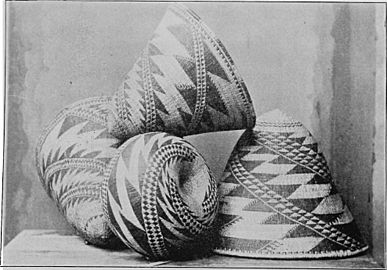

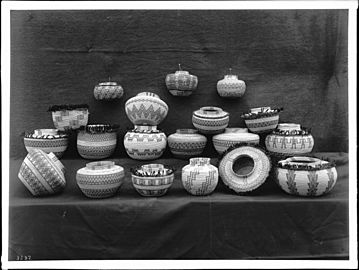

Basket making was a very important part of Native American Californian culture. Baskets were both beautiful and useful. They were woven so tightly that some could even hold water for cooking. Tribes made baskets in many shapes and sizes for different daily tasks. These included baby baskets, collecting vessels, food bowls, cooking items, and ceremonial items. They also made wearable basket caps for both men and women. The watertight cooking baskets were often used to make acorn soup. Hot stones were placed in the baskets with food mixtures and stirred until cooked.

Women generally made baskets. Girls learned the process from a young age. This included not just weaving, but also how to care for, harvest, and prepare the plants needed for weaving.

-

Yokuts woman making a basket, Tule River Reservation around 1900

-

Pomo baskets with a zigzag pattern

Foods

Native Californians had many different food sources. They had access to hundreds of types of edible plants, land and sea animals, birds, and insects. This variety was very important. If one food source was low, they had many others to rely on. Even with this abundance, Native peoples depended on 20-30 main food sources. Their diets included fish, shellfish, insects, deer, elk, antelope, and plants like buckeye and sage seed.

Plant-Based Foods

Acorns from the California Live Oak tree were a main traditional food across much of California. Acorns were ground into a meal. This meal was then boiled into mush or baked into bread. Acorns contain a lot of tannic acid, so people had to learn how to remove it. This took a lot of work. Grinding the acorns and then boiling them helped remove the tannins. Acorns were harvested in the fall and stored in large granaries in villages. This provided a reliable food source through winter and spring.

Native American tribes also used Manzanita berries as a main food. Ripe berries were eaten raw, cooked, or made into jellies. The dried pulp could be crushed to make a cider, and dry seeds were sometimes ground into flour. The bark was also used to make a tea for health.

Marine Life

Two types of marine mammals were important food sources: large migrating animals like northern elephant seals and California sea lions, and non-migrating ones like harbor seals and sea otters. Marine mammals were hunted for their meat and fat. Their furs were also very important for trade and as symbols of status.

Many different kinds of marine fish lived along California's coast. This provided food for communities living near the shore. Tribes along the coast mostly fished from the shore.

Fish from Rivers

Anadromous fish live half their lives in the sea and half in rivers, where they go to lay eggs. Large rivers like the Klamath and Sacramento provided many fish for hundreds of miles during the spawning season. Pacific salmon were especially important in the Native Californian diet. Salmon ran in California's coastal rivers and streams from Oregon down to Baja California. For groups like the Yurok and Karuk, salmon was a defining food. For example, more than half of the Karuk people's diet came from acorns and salmon from the Klamath River.

Unlike acorns, catching fish required special tools like dip nets and harpoons. Fish could only be caught during a short time each season. During this time, salmon would be harvested, dried, and stored in large amounts for later use.

Society and Beliefs

In Native societies, men and women had different roles. Women usually handled weaving, harvesting, and preparing food. Men were generally responsible for hunting and other types of labor. Early Spanish explorers noted "men who dressed as women" were an important part of Native society. The Spanish often disliked these people, calling them joyas in mission records. With colonization, joyas were often forced out of their communities and became homeless. Traditionally, joyas were responsible for death, burial, and mourning rituals, and performed women's roles.

Many tribes in Central and Northern California practiced the Kuksu religion. This was common among the Nisenan, Maidu, Pomo, and Patwin tribes. Kuksu involved detailed ceremonial dances and special clothing. A male secret society met in underground dance rooms and performed disguised dances for the public.

In Southern California, the Toloache religion was important for tribes like the Luiseño and Diegueño.

Native American culture in California is also known for its rock art. This is especially true for the Chumash of Southern California. The rock art, or pictographs, were brightly colored paintings of humans, animals, and abstract designs. They were thought to have religious meaning.

Reservations

Native American reservations are lands set aside for tribes. Here are some of the most populated reservations in California:

| Area Name | Tribe(s) | Population

(2010) |

Area in mi2 (km2) | Includes

ORTL? |

Main Town/Capital | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land | Water | Total | Tribal Council Location | ||||

| Agua Caliente Indian Reservation | Cahuilla | 24,781 | 53.32 (138.090) | 0.36 (0.94) | 53.68 (139.04) | yes | Se-Khi (Palm Springs) |

| Colorado River Indian Reservation | Chemehuevi, Mohave, Hopi, Navajo | 8,764 | 457.31 (1,184.44) | 6.83 (17.68) | 464.14 (1,202.13) | no | 'Amat Kuhwely (Parker, Arizona) |

| Torres-Martinez Reservation | Cahuilla | 5,594 | 34.22 (88.62) | 15.04 (38.96) | 49.26 (127.58) | no | Kokell (Thermal) |

| Hoopa Valley Reservation | Hupa | 3,041 | 140.77 (364.59) | 0.92 (2.38) | 141.68 (366.96) | no | Hoopa |

| Washoe Ranches Trust Land | Washoe | 2,916 | 144.99 (375.53) | 1.05 (2.71) | 146.04 (378.24) | no | Gardnerville, Nevada |

| Fort Yuma Indian Reservation | Quechan | 2,197 | 68.93 (178.53) | 1.39 (3.61) | 70.32 (182.14) | no | Yuma, Arizona |

| Bishop Reservation | Mono, Timbisha | 1,588 | 1.35 (3.50) | 0.014 (0.035) | 1.37 (3.54) | no | Bishop |

| Fort Mojave Reservation | Mohave | 1,477 | 51.58 (133.58) | 1.15 (2.99) | 52.73 (136.57) | yes | ʼAha Kuloh (Needles, California) |

| Pala Reservation | Luiseño, Cupeño | 1,315 | 20.35 (52.71) | 0 | 20.35 (52.71) | no | Pala, California |

| Yurok Reservation | Yurok | 1,238 | 84.73 (219.46) | 3.35 (8.67) | 88.08 (228.13) | no | Klamath |

| Rincon Reservation | Luiseño | 1,215 | 6.16 (15.96) | 0 | 6.16 (15.96) | yes | Sówmy/Kuutpamay (Valley Center) |

| Tejon Indian Tribe of California | Kitanemuk, Yokuts, Chumash | 1,111 | South of Woilo (Bakersfield) | ||||

| San Pasqual Reservation | Kumeyaay | 1,097 | 2.24 (5.79) | 0 | 2.24 (5.79) | no | Valley Center |

| Tule River Reservation | Yokuts, Mono | 1,049 | 84.29 (218.32) | 0 | 84.29 (218.32) | yes | Uchiyingetau(indigenous name of area) (address in Porterville) |

| Morongo Reservation | Cahuilla, Serrano | 913 | 53.48 (138.50) | 0.13 (0.33) | 53.60 (138.83) | yes | Banning |

| Cabazon Reservation | Cahuilla | 835 | 3.00 (7.77) | 0 | 3.00 (7.77) | no | Indio |

| Santa Rosa Rancheria | Yokuts | 652 | 0.63 (1.62) | 0 | 0.63 (1.62) | no | Walu(indigenous name of area) (Lemoore) |

| Barona Reservation | Kumeyaay | 640 | 9.31 (24.12) | 0 | 9.31 (24.12) | no | Lakeside |

| Susanville Indian Rancheria | Washoe, Achomawi, Northern Paiute, Atsugewi | 549 | 1.67 (4.33) | 0 | 1.67 (4.33) | yes | Susanville |

| Viejas Reservation | Kumeyaay | 520 | 2.51 (6.50) | 0 | 2.51 (6.50) | no | Alpine |

| Karuk Reservation | Karuk | 506 | 1.49 (3.85) | 0.035 (0.091) | 1.52 (3.94) | yes | Athithúf-vuunupma (Happy Camp) |

Native Peoples of California

- Achomawi, Achumawi, Pit River tribe

- Atsugewi

- Chemehuevi

- Chumash

- "Barbareño"

- "Cruzeño, Isleño"

- "Emigdiano"

- "Interior"

- "Inezeño", "Ineseño"

- "Obispeño"

- "Purisimeño"

- "Ventureño"

- Chilula

- Chimariko (extinct)

- Kuneste, "Eel River Athapaskan peoples"

- Lassik

- Mattole (Bear River)

- Nongatl

- Sinkyone

- Wailaki

- Esselen

- Hupa

- Karok

- Kato, Cahto

- Kawaiisu

- Konkow

- Kumeyaay, Diegueño, Kumiai

- Ipai

- Jamul

- Tipai

- Ipai

- La Jolla complex

- Maidu

- Konkow

- Yamani, Mechoopda

- Nisenan, Southern Maidu

- Miwok

- Bay Miwok

- Coast Miwok

- Lake Miwok

- Valley and Sierra Miwok

- Monache, Western Mono

- Mohave

- Nisenan

- Nomlaki

- Ohlone, Costanoan

- Patwin

- Suisun, Southern Patwin

- Pauma Complex

- Pomo

- Quechan, Yuman

- Te'po'ta'ahl, ("Salinan")

- "Antoniaño"

- "Migueleño"

- "Playano"

- Shasta

- Konomihu

- Okwanuchu

- Tolowa

- Takic

- Tubatulabal

- Bankalachi

- Pahkanapil

- Palagewan

- Wappo

- Whilkut

- Wintu

- Wiyot

- Yana

- Yokuts

- Chukchansi, Foothill Yokuts

- Northern Valley Yokuts

- Tachi tribe, Southern Valley Yokuts

- Timbisha

- Yuki, Ukomno'm

- Huchnom

- Yurok

Languages

Before Europeans arrived, Native Californians spoke over 300 dialects from about 100 different languages. This huge number of languages is linked to California's diverse natural environments. It's also because Native groups were often small, with 100 or fewer people. They believed that language boundaries were natural parts of the land. California had more language diversity than all of Europe combined.

Most California Native languages belong to small language families (like Yukian or Maiduan) or are unique languages (like Karuk or Esselen). Other languages are part of larger groups like Uto-Aztecan or Athapaskan. Some evidence suggests that Chumashan and Yukian languages were in California before Penutian languages from the north and Uto-Aztecan from the east. Wiyot and Yurok languages are distantly related to Algonquian languages. The Athapaskan languages arrived more recently, about 2000 years ago.

See also

In Spanish: Pueblos indígenas de California para niños

In Spanish: Pueblos indígenas de California para niños

- Aboriginal title in California

- California State Indian Museum

- Indigenous peoples of Mexico

- List of federally recognized tribes by state#California

- Martis people

- Mission Indians

- Population of Native California

- Survey of California and Other Indian Languages

Category:Native American youth scholars]][[Category:Native American