History of Bristol facts for kids

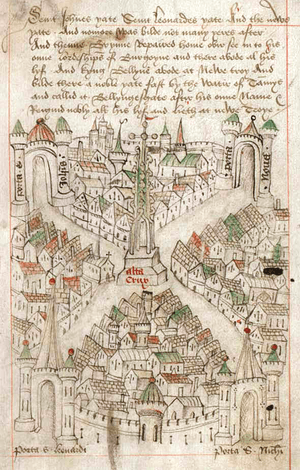

Bristol is a big city in southwest England, home to almost half a million people. It sits between Somerset and Gloucestershire on the River Avon. For about 800 years, Bristol has been one of England's most important cities for its economy and culture. People have lived in the Bristol area since the Stone Age, and there's also proof of Roman settlements. By the 900s, a place called Brycgstow (which means "place by the bridge") had a mint for making coins. The town grew a lot during the Norman times and became a county in itself in 1373. The name changed to 'Bristol' because of how people in the area said the 'ow' sound.

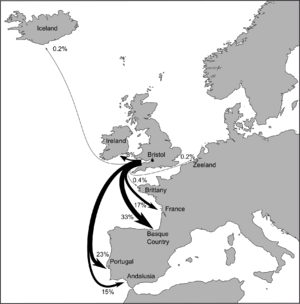

Bristol's connections by sea to Wales, Ireland, Iceland, France, Spain, and Portugal helped trade grow steadily. They traded things like wool, fish, wine, and grain during the Middle Ages. Bristol officially became a city in 1542. After this, trade across the Atlantic Ocean became very important. During the English Civil War, Royalist troops captured the city, but Parliament's forces later took it back. The 1600s and 1700s brought more wealth to Bristol because of the transatlantic slave trade and the Industrial Revolution. Important people like Mary Carpenter and Hannah More worked hard to end the slave trade.

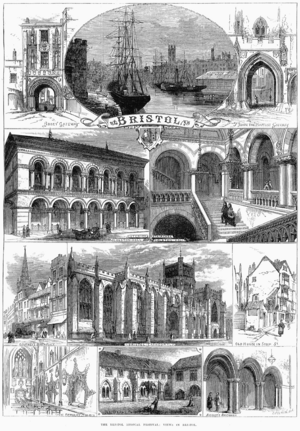

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, Bristol built a special "floating harbour." This helped ships stay afloat no matter the tide. Shipbuilding also improved, and industries like glass, paper, soap, and chemicals grew. Bristol became a major railway hub thanks to the Great Western Railway, designed by I. K. Brunel. In the early 1900s, Bristol was a leader in making aircraft. By the start of the 2000s, the city had become an important center for money and high-tech businesses.

Contents

Bristol's Early History: Before the Normans Arrived

Who Lived in Bristol During the Stone Age and Iron Age?

We know people lived in the Bristol area as far back as the Stone Age. Archaeologists have found tools from 60,000 years ago in places like Shirehampton and St Annes. These tools were made from different kinds of stone and found near the River Avon. There are also Iron Age hill forts close to the city, like at Leigh Woods and Clifton Down. These forts were built by the Dobunni tribe. Digs in Bristol have also found signs of Iron Age farms, for example, at Filwood.

What Was Bristol Like During Roman Times?

During the Roman era, there was a settlement called Abona where Sea Mills is today. This town was important enough to be listed in a Roman travel guide from the 200s. It was connected to Bath by a road. When archaeologists dug at Abona, they found streets, shops, cemeteries, and docks. This shows it was a busy port. Other small Roman settlements and villas were also found in the area, like the Kings Weston Roman Villa.

How Did Bristol Start in Saxon Times?

A church called a minster was built in the 700s at Westbury on Trym. The town of Bristol itself started on a low hill between the River Frome and the Avon rivers sometime before the early 1000s. We know this because coins from around 1010 were found, showing it was a market town. The name Brycg stowe meant "place by the bridge." The local accent might have changed Brycg stowe to the name 'Bristol' we use today.

St Peter's church, which you can still see parts of in Castle Park, might have been another important church from the 700s. By the time the Domesday Book was written, this church owned a lot of land. Old records also show that in 1052, Harold Godwinson sailed from Brycgstow. This proves the town was already a busy port.

Brycg stowe was a big center for the Anglo-Saxon slave trade. People captured in Wales or northern England were sold through Bristol to Dublin. From there, Viking rulers in Dublin would sell them to other parts of the world. The local bishop, Wulfstan, spoke out against this trade. Eventually, the king banned it, but it continued secretly for many years.

Bristol in the Middle Ages

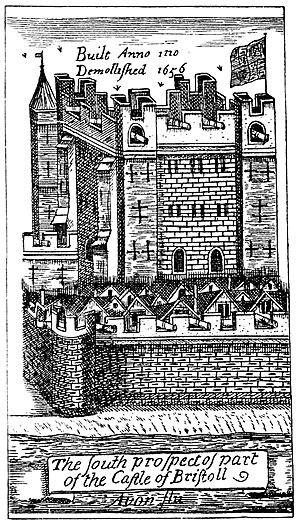

The Norman Era: Building Bristol Castle

After the Norman conquest of England in 1066, a motte-and-bailey castle was built where Castle Park is now. Geoffrey de Montbray, a bishop who came with William the Conqueror, controlled Bristol. William wanted stone castles built, so Geoffrey likely started building Bristol Castle. After William died, Geoffrey rebelled against the new king, William Rufus. He used Bristol as his base to attack nearby areas before giving up.

King Rufus then gave Bristol and the surrounding area to Robert Fitzhamon. Fitzhamon made Bristol Castle bigger and stronger. His daughter Mabel married King Henry I's son, Robert of Caen. Robert of Caen became the first Earl of Gloucester and is thought to have finished building Bristol Castle.

In 1135, King Henry I died. The Earl of Gloucester supported his sister Empress Matilda in her fight against Stephen of Blois for the throne. Stephen tried to attack Robert at Bristol in 1138 but gave up because the castle was too strong. When Stephen was captured in 1141, he was held in the castle. But when Robert was captured by Stephen's forces, Matilda had to trade Stephen for Robert. Her son Henry, who would later become Henry II of England, was kept safe in the castle and taught by his uncle Robert. The castle later became royal property, and King Henry III spent a lot of money making it even grander.

In 1137, the Earl of Gloucester founded the St James Priory. In 1140, St Augustine's Abbey was founded by Robert Fitzharding, a rich Bristolian who had supported the Earl and Matilda. As a reward, he later became Lord of Berkeley. This abbey was a monastery for Augustinian canons. In 1172, King Henry II gave Bristolians the right to live and trade in Dublin, Ireland. There was also a small Jewish community in Bristol during the early Middle Ages, as shown by a surviving Jewish ritual bath called Jacob's Well.

How Bristol Grew in the Later Middle Ages

By the 1200s, Bristol was a very busy port. Woollen cloth became its main export from the 1300s to the 1400s. Wine from France was the main import. Bristol also traded a lot with Irish ports like Waterford and Cork, and with Portugal. From about 1420 to 1480, the port also traded with Iceland, bringing in dried cod called 'stockfish'.

In 1147, Bristol ships and men helped in the Siege of Lisbon, which led to that city being taken back from the Moors. A stone bridge was built across the Avon around 1247. Between 1240 and 1247, a "Great Ditch" was dug to make the River Frome straighter, creating more space for ships to dock.

Redcliffe and Bedminster became part of the city in 1373. King Edward III declared that Bristol would be its own county, separate from Gloucestershire and Somerset. This meant that legal problems could be solved in Bristol's own courts. The city walls were extended into Redcliffe. You can still see a major part of the walls next to the only remaining gateway, under the tower of the Church of St John the Baptist.

By the mid-1300s, Bristol was thought to be England's third-largest town, after London and York. It had about 15,000 to 20,000 people before the Black Death plague hit in 1348–49. The plague caused a big drop in population, which stayed between 10,000 and 12,000 during the 1400s and 1500s.

One of Bristol's first great merchants was William Canynge. He was mayor five times and a Member of Parliament twice. He reportedly owned ten ships and employed over 800 sailors. Later in life, he became a priest and spent a lot of his money rebuilding St Mary Redcliffe church, which had been badly damaged by lightning.

The end of the Hundred Years' War in 1453 meant Britain, and Bristol, lost access to French wines. So, imports of Spanish and Portuguese wines increased. Imports from Ireland included fish, animal hides, and cloth. Bristol exported cloth, food, clothing, and metals to Ireland.

Some people thought that the decline of Bristol's trade with Iceland for dried cod hurt the local economy. This might have encouraged Bristol merchants to look west, launching voyages into the Atlantic by 1480 to find the mythical island of Hy-Brazil. However, newer research shows that the Iceland trade was only a small part of Bristol's overseas trade. Also, English fishing off Iceland actually grew in the late 1400s and 1500s. In 1487, when King Henry VII visited, people complained about the economy. But such complaints were common when towns wanted to avoid taxes or get favors from the king. In reality, Bristol's trade was growing strongly in the late 1400s, especially with Spain.

Bristol's Role in Early Exploration

In 1497, Bristol was the starting point for John Cabot's journey to North America. For many years, Bristol merchants bought dried cod from Iceland. But the Hanseatic League, which tried to control trade in the North Atlantic, tried to stop supplies to English merchants. Some believe this made Bristol's merchants look west for new sources of cod. However, while Bristol merchants did largely leave Iceland in the late 1400s, other English merchants continued to trade there. Also, English fishing off Iceland actually grew from the 1490s, just in a different area. This makes it harder to say Bristol merchants were "pushed out" of Iceland.

In 1481, two local men, Thomas Croft and John Jay, sent ships to find the mythical island of Hy-Brasil. They didn't find the island, but Croft was charged for illegally exporting salt. Some historians think these explorers might have found the Grand Banks off Newfoundland, which are waters full of cod.

John Cabot was supported by King Henry VII for his 1497 voyage. He was looking for a new way to reach Asia. Instead, he found North America. When he returned, Cabot spoke of the huge amounts of cod near this new land. In 1498, Cabot sailed again from Bristol with five ships. He is believed to have never returned from this trip, though some recent research suggests he might have.

From 1499 to 1508, several other expeditions sailed from Bristol to the "New found land." One of these, led by John Cabot's son, Sebastian Cabot, explored the coast of North America. He went so far south that he was "almost in the latitude of Gibraltar" and "almost the longitude of Cuba." This means he likely reached as far as the Chesapeake Bay, near where Washington D.C. is today.

Bristol in Early Modern Times

Tudor and Stuart Periods: Becoming a City and Civil War

Bristol officially became a city in 1542. The old Abbey of St Augustine became Bristol Cathedral after King Henry VIII closed down the monasteries. Many other religious houses in Bristol were also closed. In 1541, Bristol's leaders bought up lands and properties that used to belong to these religious places for a thousand pounds. This made Bristol the only city in the country to own its own chapel, at St Mark's.

Bristol Grammar School was started in 1532, and in 1596, John Carr founded Queen Elizabeth's Hospital, a school for "poor children and orphans."

Trade continued to grow. By the mid-1500s, Bristol imported wine, olive oil, iron, figs, and dyes from Europe. It exported cloth, lead, and animal hides. Many leading merchants in the city were involved in smuggling, secretly exporting goods like food and leather, and not declaring all their wine imports.

In 1574, Elizabeth I visited Bristol during her tour of western England. The city spent over a thousand pounds on preparations and entertainment for her visit. In 1577, the explorer Martin Frobisher arrived in Bristol with two ships and samples of ore, which turned out to be worthless. He also brought three "savages," likely Inuit people, who sadly died within a month.

Bristol sent three ships to help the Royal Navy fight the Spanish Armada in 1588. It also provided men for the land forces. The city had to repair its walls and gates. Bristol Castle was not used much by the late 1500s, and the area around it became a place where lawbreakers could hide.

Bristol During the English Civil War

In 1630, the city bought the castle. When the First English Civil War began in 1642, Bristol sided with Parliament and partly fixed up its defenses. However, Royalist troops led by Prince Rupert captured Bristol on July 26, 1643. This caused a lot of damage to the town and castle. The Royalists took many valuable things and eight armed merchant ships, which became the start of their navy. Workshops in Bristol became arms factories, making muskets for the Royalist army.

In the summer of 1645, Parliament's New Model Army defeated the Royalists at the Battle of Langport in Somerset. After more wins, Sir Thomas Fairfax marched on Bristol. Prince Rupert returned to organize the city's defense. Parliament's forces surrounded the city and attacked after three weeks, forcing Rupert to surrender on September 10. The First Civil War ended the next year. There were no more battles in Bristol during the second and third civil wars. In 1656, Oliver Cromwell ordered the castle to be destroyed.

Bristol's Role in the Slave Trade

William de la Founte, a rich Bristol merchant, is known as the first recorded English slave trader. In 1480, he was given permission to "trade in any parts."

Bristol grew again in the 1600s with the rise of England's American colonies. In the 1700s, Bristol's part in the "Triangular trade" grew very quickly. This trade involved taking Africans to the Americas for slavery. Over 2,000 slave voyages were made by Bristol ships between the late 1600s and when the trade was abolished in 1807. These ships carried an estimated half a million people from Africa to the Americas in terrible conditions. The average profit for each voyage was seventy percent. More than fifteen percent of the Africans transported died or were murdered during the journey. Some enslaved people were brought to Bristol from the Caribbean, like Scipio Africanus and Pero Jones.

The slave trade created a big demand for cheap brass goods to export to Africa. This caused a boom in the copper and brass industries in the Avon valley, which helped the Industrial Revolution begin in the area. Important manufacturers like Abraham Darby and William Champion built large factories. These factories used ores from the Mendips and coal from the North Somerset coalfield. Water power from rivers helped run the machines until steam power was developed later in the 1700s. Other industries like glass, soap, sugar, paper, and chemicals also grew along the Avon valley.

Edmund Burke became a Whig Member of Parliament for Bristol in 1774. He supported free trade and the rights of the American colonists. However, he angered his merchant supporters because he hated the slave trade, and he lost his seat in 1780.

People who fought against slavery, inspired by preachers like John Wesley, started some of the earliest campaigns against it. Important local people who opposed slavery included Anne Yearsley, Hannah More, Mary Carpenter, and Robert Southey. This campaign also helped start movements for other reforms and for women's rights.

Bristol in the 18th and 19th Centuries

The Bristol Corporation of the Poor was set up in the late 1600s. A workhouse was built to provide work for the poor and shelter for those who needed help. John Wesley founded the very first Methodist Chapel, The New Room, in Broadmead in 1739. It is still used today. Wesley came to Bristol after being invited by George Whitfield. He preached outdoors to miners and brickworkers in Kingswood and Hanham.

Bristol Bridge, the only way to cross the river without a ferry, was rebuilt between 1764 and 1768. The old medieval bridge was too narrow for all the traffic. A toll was charged to pay for the work. In 1793, when the toll was extended for longer, the Bristol Bridge Riot happened. Eleven people were killed and 45 injured, making it one of the worst riots of the 1700s.

Bristol faced tough competition from Liverpool starting in 1760. Wars with France (1793) also disrupted sea trade, and the abolition of the slave trade (1807) hurt the city. Bristol struggled to keep up with newer manufacturing centers in the North and Midlands. The cotton industry didn't grow in the city, and sugar, brass, and glass production declined. Some historians say that a "certain complacency" from Bristol's leading merchant families made it hard for the city to adapt to the new conditions of the Industrial Revolution.

The long journey up the Avon Gorge, which had made the port very safe in the Middle Ages, became a problem. Building a new "Floating Harbour" (designed by William Jessop) between 1804 and 1809 didn't fully solve this. Still, Bristol's population (61,000 in 1801) grew five times bigger during the 1800s, supported by growing trade. The city is especially linked to the famous engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel. He designed the Great Western Railway between Bristol and London. He also designed two pioneering Bristol-built steamships, the SS Great Western and the SS Great Britain, and the Clifton Suspension Bridge.

A new middle class, led by those who fought against the slave trade, began to do charity work in the city. Notable people included Mary Carpenter, who started schools for poor children, and George Müller, who founded an orphanage in 1836. Badminton School started in 1858, and Clifton College was established in 1862. University College, which later became the University of Bristol, was founded in 1876.

The Bristol Riots of 1831 happened after the House of Lords rejected a bill to reform voting laws. A local judge, Sir Charles Wetherall, who strongly opposed the bill, visited Bristol. An angry crowd chased him to the Mansion House. The Reform Act was passed in 1832. After this, Bristol's city boundaries were expanded for the first time since 1373 to include areas like Clifton and parts of Bedminster.

Bristol is located on a smaller coalfield in the UK. From the 1600s, coal mines opened in Bristol and nearby areas. While these led to the building of the Somerset Coal Canal, it was hard to make mining profitable, and the mines closed after they were taken over by the government.

By the end of the 1800s, the main industries were tobacco and cigarette making, led by the W.D. & H.O. Wills company, along with paper and engineering. The port facilities started moving downstream to Avonmouth, where new factories were built.

Bristol's Modern History

From Airplanes to Modern Industries

The British and Colonial Aeroplane Company, which later became the Bristol Aeroplane Company, was founded by Sir George White in 1910. During World War I, the company became famous for making the Bristol Scout and the Bristol F.2 Fighter. Their main base at Filton is still an important manufacturing site for BAE Systems today. The engine part of the Bristol Aeroplane Company became Rolls-Royce plc in 1966, and it is still based at Filton. Shipbuilding in the city docks remained important until the 1970s. Other major industries included chocolate makers J. S. Fry & Sons and wine importers John Harvey & Sons.

Bristol City F.C. (formed in 1897) joined the Football League in 1901. Bristol Rovers F.C. (formed in 1883) joined the league in 1920. Gloucestershire County Cricket Club was formed in 1870.

Between 1919 and 1939, Bristol City Council built over 15,000 houses. This helped clear some of the worst slum areas in the city center. New housing estates were built in places like Southmead and Sea Mills. The city boundaries were expanded to include these new areas. In 1926, the Portway, a new road along the Avon Gorge costing about £800,000, was opened. It connected the floating harbor to the growing docks at Avonmouth.

World War II and Social Change

Because Bristol made aircraft and was a major port, it was a target for bombing during the Bristol Blitz of World War II. Bristol's city center was badly damaged, especially in November and December 1940. The original central area, near the bridge and castle, is now a park with two bombed churches and parts of the castle. The Broadmead shopping center and Cabot Circus were built over areas damaged by bombs.

After the war, people from different Commonwealth countries moved to British cities, including Bristol. This sometimes led to racial tension. In 1963, the Bristol Omnibus Company refused to hire Black or Asian bus crews. This was successfully challenged by the Bristol Bus Boycott. This boycott was very important in leading to the Race Relations Act 1968, which made discrimination illegal. In 1980, a police raid on a cafe in St Paul's sparked the St Pauls riot, which showed the difficulties faced by the city's ethnic minorities.

Bristol's aviation industry continued to grow after the war. The Bristol Brabazon was a large trans-Atlantic airplane built in the late 1940s, but it was never sold. Concorde, the first supersonic airliner, was built in the 1960s and first flew in 1969. While Concorde didn't become a big commercial success, its development helped create the successful Airbus series of airliners, parts of which are still made at Filton today.

Bristol Today: Technology and Regeneration

In the 1980s, financial services became a major employer in Bristol and the surrounding areas. High-tech companies like IBM, Hewlett Packard, Toshiba, and Orange, along with creative and media businesses, became important local employers as older manufacturing industries declined.

Like many British cities after the war, Bristol's city center was rebuilt with large, cheap tower blocks and lots of new roads. Since the 1990s, this trend has changed. Some main roads have been closed, and the Broadmead shopping center has been improved. In 2006, one of the city center's tallest post-war buildings was torn down. Older social housing tower blocks have also been replaced with lower homes.

Moving the docks to Avonmouth, seven miles downstream from the city center, helped reduce traffic in central Bristol. This allowed for a lot of redevelopment in the old central dock area (the Floating Harbour) in the late 1900s. The deep-water Royal Portbury Dock was built in the 1970s. After the Port of Bristol became a private company, it became very successful.

At one point, the old central docks were almost removed because they were seen as just old industry. But since the 1980s, millions of pounds have been spent redeveloping the harborside. In 1999, the city center was redeveloped, and Pero's footbridge was built. This bridge now connects the At-Bristol science center, which opened in 2000, with other Bristol tourist attractions. Private investors are also building new apartments. The redevelopment of the Canon's Marsh area is expected to cost £240 million.

Images for kids

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |