1893 San Roque hurricane facts for kids

| Category 3 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

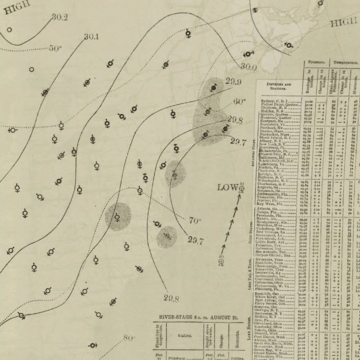

Surface weather analysis of Hurricane Three on August 21, 1893, off the Mid-Atlantic U.S. coast

|

|

| Formed | August 13, 1893 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | August 22, 1893 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 120 mph (195 km/h) |

| Fatalities | 37 |

| Damage | Unknown |

| Areas affected | Lesser Antilles, Puerto Rico, New England, Atlantic Canada |

| Part of the 1893 Atlantic hurricane season | |

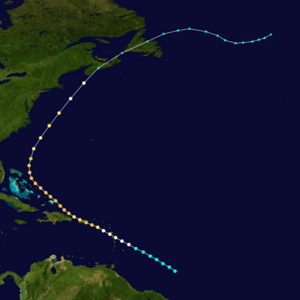

Hurricane San Roque was a powerful tropical cyclone that hit Puerto Rico, eastern New England, and Atlantic Canada in August 1893. It was called "San Roque" in Puerto Rico because it arrived on the feast day of Saint Roch, or San Roque in Spanish. This storm was the third known hurricane of the 1893 Atlantic hurricane season.

The storm was first seen on August 13, 1893, far east of the Lesser Antilles. It grew stronger as it moved slowly through the Caribbean Sea. On August 17, it hit Puerto Rico as a very strong storm, like a Category 3 hurricane on today's Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale. The calm center of the storm, called the eye, took about seven hours to cross the island from southeast to northwest.

Strong winds for a long time caused a lot of damage in Puerto Rico, especially along the northern coast. Many homes were damaged, and simple shacks belonging to poor workers were hit the hardest. Many families lost their homes, and four people died. Telegraph lines were cut across the island. Heavy rains for several days also caused big floods in rivers further inland. The strong winds and rain together destroyed many crops, like coffee and sugar cane.

On August 19, the hurricane started to turn northeast, speed up, and get weaker. Even though its center stayed far from the United States, heavy rain and strong winds hit the country's East Coast on August 20 and 21. Eastern New England felt like it was having a really bad nor'easter, which is a strong winter storm. Winds as fast as 72 mph (116 km/h) were recorded on Block Island. In Rhode Island and Massachusetts, grain crops were flattened, and fruit trees lost all their fruit. A famous racing yacht called Volunteer was badly damaged. A fishing schooner sank off Nantucket, and only one of its seven crew members survived by holding onto floating pieces for 33 hours.

Later that day, the fast-moving storm hit Nova Scotia in Canada. Power and communication lines were cut in Halifax. The storm caused a lot of trouble for ships and boats all over Atlantic Canada. It became known as "one of the most famous marine storms in the history of Nova Scotia." The worst sea accident was when the steamship Dorcas and its barge Etta Stewart hit a rocky area east of Halifax. The Dorcas flipped over and was pushed onto the shore, while the barge broke apart. All 24 people on both vessels died. Two more people died when their boat sank on Trinity Bay in Newfoundland. In total, 37 people died because of the storm.

Contents

How the Storm Formed and Moved

We don't know much about Hurricane San Roque's early days because there weren't many weather reports back then. It likely started in a low-pressure area near the equator, off the coast of South America. Weather records show it became a tropical storm on August 13, about 730 miles (1,170 km) east of Trinidad and Tobago.

It crossed the Lesser Antilles islands on August 15, passing between Dominica and Guadeloupe. The storm got stronger and moved northwest. By August 16, it was very close to St. Croix. When the first report of the storm came from Saint Thomas, the U.S. Weather Bureau sent out a special warning. They told ships to be careful because the hurricane was expected to turn north by August 21.

On August 17, the storm hit near Patillas, Puerto Rico. It was as strong as a Category 3 hurricane. Experts today figured out its strength by looking at how much wind damage it caused in Puerto Rico. The calm eye of the storm passed over the island. When the eye was overhead, some people thought the storm was over because it became so quiet. The air pressure in San Juan dropped a lot. About seven hours after hitting land, the center of the storm moved off Puerto Rico's coast.

On August 18, weather stations along the Atlantic coast of the Southeastern U.S. started to feel the hurricane's effects, even from far away. The storm passed over or near the Turks and Caicos Islands. By August 19, when it was northeast of the Bahamas, the hurricane began to turn north and then northeast.

Late on August 20 and into August 21, strong winds and heavy rain hit the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast coasts. The hurricane got weaker as it moved north. On August 21, it passed about 185 miles (298 km) east of Cape Hatteras. Later that day, the fast-moving storm passed within 150 miles (240 km) of Nantucket. On August 22, this was one of four hurricanes active in the Atlantic Ocean. It was the first of three storms to hit the U.S. East Coast in just eight days.

Even though some experts today say the storm was still a hurricane when it reached Nova Scotia, official studies found no clear proof of hurricane-force winds in Canada. In the early morning of August 22, the storm hit Nova Scotia near St. Margarets Bay. By then, it had changed into an extratropical cyclone, which is a different type of storm. Its path meant that Halifax was hit by the strongest part of the storm. This kind of hit wouldn't happen again until Hurricane Juan in 2003. After quickly crossing Nova Scotia, the storm's leftover parts hit the island of Newfoundland. Its path was tracked for several more days as it moved eastward into the North Atlantic.

Storm's Effects

The strengthening hurricane brought stormy weather to the Lesser Antilles, from Martinique to the Virgin Islands. In Saint Thomas, boats and docks were damaged, trees were blown down, and roofs were torn off houses.

Puerto Rico Impact

For the first time in Puerto Rico's history, special flags were used to warn people about the coming hurricane. Officials in San Juan first put up red warning flags on the morning of August 16. Three hours later, they changed to more urgent yellow and blue flags, and finally to black flags as the storm began. By mid-afternoon, the Port of San Juan was closed. Even though ships were told to leave the port, there wasn't enough time or enough tugboats, so some ships had to stay put and face the storm. Ships at the docks had to unload their goods. When it became clear how bad the hurricane was, local officials made sure ships were tied down well and moved them to safer spots to avoid crashes. Bus and tram services stopped as the weather got worse, leaving many people unable to get home for the night.

On the night of August 16–17, winds of 55 mph (89 km/h) were recorded in San Juan and 50 mph (80 km/h) in Mayagüez. After that, the wind measuring tools, called anemometers, were blown away. The storm was so damaging not just because it was strong, but because it lasted for a very long time.

The northern coast was hit the hardest. The storm destroyed crops, telegraph lines, and buildings. Simple shacks and huts, where poor workers lived, were damaged the most. In Camuy, the storm destroyed up to 20 houses, pulled trees out of the ground, and caused two small fires. After the storm, the mayor set up a special group to help get money to the storm victims. Many homeless families received help from their neighbors. The winds tore roofs off many small huts near the shore of Arecibo, forcing people to run for safety. Wooden and brick fences were knocked down. The local telegraph station stopped working, which made it slow to get news about the damage.

Both the city and rural areas of Manatí had a lot of damage. Dozens of thatch roofs were blown off, and some homes couldn't be lived in anymore. The basement of a large building was used as a temporary shelter for poor and injured storm victims. Many people in Hatillo lost their homes, and reports said trees were blown far from where they used to stand. Vega Baja was badly damaged, with at least 28 houses destroyed and many banana, coconut, and other fruit trees knocked over. Eight houses were destroyed in Isabela, and one family needed to be rescued after their home was crushed by a roof from another building. Many poor families became homeless. Some were offered shelter in the homes of local government officials. A church entrance area in the town was also destroyed.

Many more simple homes were destroyed in Bayamón, along with the roofs of bigger buildings. All telegraph wires and poles in the area were blown down. Seven or eight houses were destroyed in Trujillo Alto. The storm was not as bad as feared in Utuado, but banana farms suffered. In Dorado, many houses were damaged, and six were destroyed. Their residents had to find shelter in government buildings.

The storm was not as severe in San Juan as in other towns, but there was still a lot of damage. One hospital was badly damaged, with the roof over the maternity ward torn off. Wood and metal roof tiles were blown far away, and patients had to be moved to a nearby military hospital. Another hospital was also unroofed. With telegraph wires down everywhere, San Juan had no contact with the rest of the island at first. Many gas streetlights were broken. Palm and fruit trees were pulled up throughout the city, while garden fences and awnings were blown down. Many houses, huts, businesses, and public buildings around San Juan had different levels of damage. Several houses in the nearby town of Cataño were completely destroyed.

Heavy rainfall lasted two to three days in some places. San Juan received 2.36 inches (60 mm) of rain. Further inland, rivers overflowed their banks because of the heavy rain, flooding large areas of low land. Major rivers like the Río Grande de Arecibo, Río Grande de Manatí, and Santiago flooded. The floodwaters ruined crops like rice, corn, and sugar cane. One farmer near the eastern coast lost about 80 acres (32 ha) of sugar cane fields. The Marina neighborhood in Gurabo had to be evacuated because of river flooding. The town's mayor started a collection for poor families. Many railways and main roads, including the road between Cataño and Bayamón, were blocked by fallen trees and deep floodwaters. With mail routes blocked and telegraph lines cut, it took a long time to find out the full extent of the damage. The day after the storm, workers began to clear railways and fix communications.

Several ships were destroyed, and others were left stuck on the beach. The schooner Enriqueta broke free and crashed into a pier. The sloop Tomasito ran aground, crushing its bottom. Another sloop, the Maria Artau, went ashore at Palo Seco, but all its crew were saved by another boat. In Arecibo, the British schooner Robbie Godfrey broke free from its moorings in port while being loaded with sugar. The ship was pushed aground and destroyed, along with its cargo, but all the crew were able to reach the shore with help from rescue teams. One crewman was hurt and went to the hospital. The schooner Martiniguesi, carrying cattle to Martinique, went ashore at Maunabo. One crewman and many cattle died. The sloop Pepito was lost at Cataño. Sea baths along the shore were also destroyed.

The loss of the year's coffee crop was the most significant agricultural damage. In Lares alone, coffee losses were estimated at 500,000 Puerto Rican pesos. In some areas, only crops in sheltered valleys survived. As much as 60% of the coffee harvest was lost in Comerío. The storm was locally called "San Roque" because it started on the feast day of Saint Roch, known as San Roque in Spanish. It was one of the last big tropical cyclones to affect Puerto Rico before the island came under United States rule in 1898. Some people at the time compared it to the very damaging San Felipe hurricane of 1876. The hurricane caused four known deaths in Puerto Rico.

United States Impact

On the very edge of the hurricane, parts of Florida had strong winds. Winds reached 35 mph (56 km/h) in Key West and 38 mph (61 km/h) in Jupiter on August 20. A closer pass by New England the next day brought severe storm conditions, like a bad nor'easter. Winds reached 72 mph (116 km/h) on Block Island and 52 mph (84 km/h) on Nantucket. In Woods Hole, Massachusetts, winds up to 60 mph (97 km/h) were reported. Strong winds reached as far north as Eastport.

The Hartford Courant newspaper said the hurricane was "the most severe August storm known for many years" in Chatham. In Oak Bluffs on Martha's Vineyard, it was "without a precedent during the summer season," according to The Boston Globe. The U.S. Weather Bureau had predicted bad weather for several days, and warning signals were put up along the coast 24 hours before the storm. Because of these warnings, most ships avoided major losses.

Across Cape Cod and the Islands, trees, fences, and power lines were blown down. Apple and pear trees lost their fruit, and vegetable crops were damaged. Floodwaters filled streets and basements, while the heavy rain pushed its way into east-facing walls. Many roads were covered with broken branches from large trees. Some smaller trees and bushes were completely pulled out of the ground. Part of the Nantucket Railroad was washed away, and docks on the island had minor damage.

On the morning of August 21, the fishing schooner Mary Lizzie from Portland, Maine sank in rough seas off Nantucket. Six of the seven crew members drowned. The one survivor held onto floating pieces for 33 hours until a passing steamship rescued him. The racing yacht Volunteer, which won the 1887 America's Cup, broke free from where it was anchored. It was thrown onto rocks near the entrance to Hadley's Harbor on Naushon Island, Massachusetts. Big waves hit the boat, breaking much of its deck and filling its hull with water. After another yacht tried and failed to rescue Volunteer while the storm was still raging, a tugboat was able to pull the damaged boat free and tow it to a nearby dock.

The storm damaged several ships around Martha's Vineyard, including the schooners Sarah Louise and Clara Jane, and the sloop Cassie, which was left stuck on the shore. Many other fishing boats lost their anchors, sails, or fishing nets. The sea damage reached westward to New Jersey's Sandy Hook, where a yacht was destroyed.

President Grover Cleveland stayed in his summer home during the storm. His yacht was almost swept ashore but was saved. Rain in Boston started on the evening of August 20 and continued through the next afternoon, totaling 1.65 inches (42 mm). The Charles River overflowed its banks, flooding the Cambridgeport neighborhood of Cambridge up to 3 feet (0.9 m) deep. At Nantasket Beach in Hull, huge waves attracted crowds of people, photographers, and artists before the waves started damaging boardwalks and carnival game booths. Roads in Plymouth were covered with broken tree branches, and several pleasure boats in Plymouth Harbor were blown aground.

Grain crops in Rhode Island were also badly damaged. Two sailors were rescued after their boat flipped over in Newport Harbor. A fishing schooner drifted out to sea with its crew aboard. It was eventually rescued by a tugboat south of the Brenton Reef Light. Many ships waited out the storm in the shelter of Dutch Island in Narragansett Bay. They were "tossed like small shells on the swirling waters," as described by a newspaper. One of the Ethel Swift's two anchor chains broke, causing it to crash on the western shore of the bay. The schooner's crew of four was safely rescued. Further up the bay, three ships were blown aground on Prudence Island. A yacht race planned for August 21 around Newport was postponed because of the bad weather. About 17 fire alarm call boxes in Charlestown, Rhode Island, stopped working, so firefighters had to patrol the town all night on August 20–21.

Canada Impact

Even though it was weaker, the storm hit the Atlantic provinces of Canada hard. Michael L. MacDonald wrote that it was "one of the most famous marine storms in the history of Nova Scotia." There, the storm became known as the "Second Great August Gale," referring to a very bad hurricane in August 1837. Across the Maritimes, dozens of large ships were stuck or destroyed. Warning signals were put up in Nova Scotia on the evening of August 20 and taken down around midday on August 22.

In Halifax, rain and wind started in the early afternoon on August 21 and got worse through the night. The city went dark and was cut off from the outside world as electricity and communication wires fell. Broken power lines caused small fires and were dangerous. Parks, public gardens, and cemeteries across the city were badly damaged, with many large trees destroyed. Many ships and boats were wrecked or blown ashore in Halifax Harbour. In one case, after hitting a dock and being struck by two small boats, the schooner Janie R.'s cargo of lime swelled with seawater, causing the ship to burst open. Trees were pulled up and chimneys fell in Liverpool. The storm was less severe in Yarmouth, at the western end of the province, but it still washed out streets and blew down trees. The winds damaged trees, fences, and some buildings in Amherst, and flattened crops in the nearby countryside. In Cumberland County, a bridge was badly damaged, and two barques (types of sailing ships) were blown ashore. Several schooners were wrecked along the shores of Cape Breton. In Ingonish, two ships were left stuck on the shore, and six fishing boats drifted out to sea. People in the rural community left their homes during the worst of the storm to find shelter in nearby valleys.

Late on the night of August 21, the steamship Dorcas, with its barge Etta Stewart in tow, crashed on a very dangerous reef near the entrance to Three Fathom Harbour. Both vessels were carrying coal from Sydney to Halifax. It's likely that the barge took on water in the rough seas, making it impossible to steer. This caused both ships to drift towards the shore in the strong southerly winds. After hitting the rocks, the steamer flipped over, losing its engine, boilers, and cargo, and ended up upside down on the beach. The barge broke apart, leaving pieces of wood all over the shore. All 24 crew members and passengers were killed: Dorcas had 10 crew and 5 passengers, while Etta Stewart had 8 crew and one passenger. The small community of Louisbourg, where 16 of the victims lived, was deeply affected. A rare government investigation into the disaster was opened. It concluded that the wreck was beyond the control of Captain Angus Ferguson of Dorcas, who "gave his own life trying to save those on board the two vessels." The person leading the investigation said that cutting the barge free might have given the crew and passengers of Dorcas a better chance to survive. However, he said this wasn't a good option:

"Some might think it would have been smarter for the captain of the Dorcas to separate his steamer from the barge before getting too close to the waves. This way, his ship could have tried to get back out to sea and save the larger number of people on the steamer, even if it meant sacrificing the fewer people on the barge.

"However, if Captain Ferguson had done that and successfully saved his steamer and those on board, he would have forever been called a coward when he reached land. He would have faced serious charges of purposely sacrificing the lives of many people to save his own. For a brave man, this would have been unbearable. We must agree that by acting as he did, he showed the true qualities of a noble sailor. In the dangers of such a hurricane and wild sea, he met death while doing his duty."

Despite the sad accident at Shut-In Island, the number of deaths in Nova Scotia was considered low compared to how many ships were wrecked.

A lot of storm damage, including fallen trees and telegraph wires, collapsed barns, and sunken boats along the coast, was reported in parts of New Brunswick. At Point Escuminac, winds blew at 60 to 62 mph (97 to 100 km/h) for three hours, and many fishing boats were blown ashore. A similar situation happened further north in Shippagan. The storm cut off communication between Prince Edward Island and the mainland, and caused widespread damage across the province. Streets in the capital city of Charlottetown were covered with fallen tree branches. In rural areas, barns were destroyed. A part of the breakwater (a wall built to protect a harbor) in Souris was washed away. Fishing boats in Tignish were shattered. In Percé, on the eastern tip of Quebec's Gaspé Peninsula, 14 fishing boats were destroyed. The storm's leftover parts continued to cause strong winds over Newfoundland, ruining crops and damaging homes that were being built. The sinking of a boat in Trinity Bay led to the deaths of two men, including David C. Webber, who was a member of the local government in Newfoundland. St. John's reported powerful winds that knocked over trees.

Images for kids