Food security during the COVID-19 pandemic facts for kids

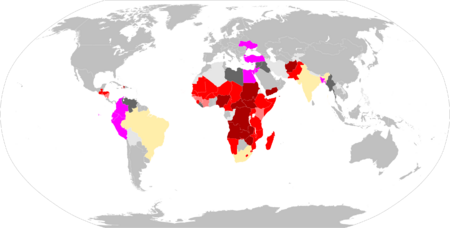

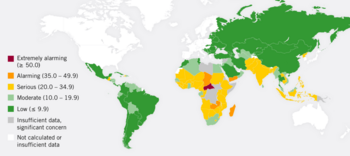

Acute food insecurity estimates for 2020 using the IPC scale

|

|

| Date | 1 December 2019–present |

|---|---|

| Duration | 6 years, 2 months and 3 weeks |

| Location |

Multiple countries

|

| Cause | 2019–2021 locust infestation, ongoing armed conflicts, COVID-19 pandemic (including associated recession, lockdowns and travel restrictions) |

During the COVID-19 pandemic, it became harder for many people to get enough food. This is called food insecurity. In mid-2020, many groups warned that serious hunger, or famine, could happen later that year.

A group called Oxfam-International talked about "economic devastation." Another report said COVID-19 was like a "poverty tsunami." Some even called it a "threat of catastrophic global famine." When the World Health Organization (WHO) said COVID-19 was a worldwide pandemic in March 2020, it added to fears of a huge global disaster.

However, studies in over 60 countries during 2020 showed something different. While there were some problems with food supplies early on, a huge global famine didn't happen as some experts had feared.

In September 2020, David Beasley, who leads the World Food Programme, spoke to the United Nations Security Council. He said that financial help from rich countries and banks, and allowing poorer countries to pause their debt payments, had stopped a major famine. This help saved 270 million people from starving. As the food problems from the pandemic started to get better, the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine caused new food problems, making prices even higher.

Why Food Problems Grew

Locust Swarms

In 2018, unusual heavy rains caused a huge increase in desert locusts in the Arabian Peninsula and Horn of Africa. Locusts gather in large swarms and destroy crops. This means less food for both animals and people.

The Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Bank reported that 23 countries were affected by these locust swarms. They caused about US$8.5 billion in damage. By July 2020, around 24 million people in these areas were struggling to get enough food. A new wave of locusts in June 2020 also raised fears of food shortages in places like Syria, Yemen, India, and Ethiopia.

The COVID-19 Pandemic

When the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 spread worldwide, many governments put in place national lockdowns and travel rules. These steps were meant to stop the disease from spreading.

Because of these rules and panic buying, food shortages increased. Also, help sent from richer countries to poorer ones, called remittances, decreased. Many poor workers in low- and middle-income countries lost their jobs or couldn't farm. Children also missed school meals because schools closed. These problems continued into 2021 and beyond. The 2021–2022 global supply chain crisis made it hard to deliver food. The 2021-2022 global energy crisis affected the making of fertilizers needed for growing food.

Many people died directly from COVID-19. But Oxfam said in July 2020 that even more people died because they didn't have enough food. Oxfam thought that by the end of 2020, "12,000 people per day could die from COVID-19 linked hunger." The United Nations said that 265 million people faced severe food insecurity. This was an increase of 135 million people because of the pandemic.

In April 2020, the head of the World Food Programme warned that 30 million people could die without financial help from Western countries. On July 9, Oxfam listed ten areas with "extreme hunger." These included parts of South America, Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia. Later in the year, the New York Times, the World Food Programme, and the World Health Organization all noted how lockdowns affected people's jobs and their ability to get food.

Overall, in 2020, COVID-19 mostly affected how people could get and afford food, not how much food was available. The food system kept working. The New York Times said, "Food remains widely available in most of the world, though prices have climbed in many countries." The main problem was that the world economy slowed down. This made it hard for millions of people to buy the food they needed.

The crisis also caused problems in farming, animal raising, chemical supplies, land value, markets, and jobs in agriculture. So, while COVID-19 made food security much worse, the problem came from the global economy slowing down, not from the food system itself.

Ongoing Conflicts

Many armed conflicts and displacement crises are happening around the world. These include wars in Yemen, Syria, the Maghreb, Ukraine, and Afghanistan. In areas with conflict, it's hard to grow and transport food. Wars also force many people to leave their homes, becoming refugees or displaced people. These areas are more likely to face famine and severe food shortages.

Global Report on Food Crises

On April 21, the United Nations World Food Programme warned that a famine "of biblical proportions" could happen in several parts of the world because of the pandemic. The 2020 Global Report on Food Crises said that 55 countries were at risk. David Beasley thought that in the worst case, about three dozen countries would face famine.

The United Nations predicted that the following countries would have serious food insecurity in 2020. This means people would be under "stress" (IPC phase 2), in "crisis" (IPC phase 3), in an "emergency" (IPC phase 4), or a "critical emergency" (IPC phase 5):

Afghanistan*

Afghanistan* Angola

Angola Burkina Faso*

Burkina Faso* Cabo Verde

Cabo Verde Cameroon

Cameroon CAR

CAR Chad*

Chad* Cote d'Ivoire

Cote d'Ivoire DR Congo

DR Congo El Salvador

El Salvador Eswatini

Eswatini Ethiopia*

Ethiopia* Gambia

Gambia Guatemala

Guatemala Guinea

Guinea Guinea-Bissau

Guinea-Bissau Haiti*

Haiti* Honduras

Honduras Iraq

Iraq Kenya

Kenya Lesotho

Lesotho Liberia

Liberia Libya

Libya Madagascar

Madagascar Malawi

Malawi Mali*

Mali* Mauritania*

Mauritania* Mozambique

Mozambique Myanmar

Myanmar Namibia

Namibia Nicaragua

Nicaragua Niger*

Niger* Nigeria*

Nigeria* Pakistan

Pakistan Rwanda

Rwanda Senegal*

Senegal* Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone Somalia

Somalia South Sudan*

South Sudan* Sudan*

Sudan* Syria*

Syria* Uganda

Uganda Tanzania

Tanzania Venezuela*

Venezuela* Yemen*

Yemen* Zambia

Zambia Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe

It also warned about:

Bangladesh, Rohingya Refugees in Cox's Bazar

Bangladesh, Rohingya Refugees in Cox's Bazar Colombia, among Venezuelan* migrants and refugees

Colombia, among Venezuelan* migrants and refugees Djibouti

Djibouti Ecuador, among Venezuelan* migrants and refugees

Ecuador, among Venezuelan* migrants and refugees Lebanon, among Syrian* refugees

Lebanon, among Syrian* refugees Palestine

Palestine Turkey, among Syrian* refugees

Turkey, among Syrian* refugees Ukraine, in the Luhansk and Donetsk regions.

Ukraine, in the Luhansk and Donetsk regions.

An asterisk (*) means Oxfam considered that country an "extreme hunger" hotspot in July 2020. These ten areas, including Afghanistan, DR Congo, Ethiopia, Haiti, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Venezuela, Yemen, and the West African Sahel, had 65% of all people facing crisis-level hunger. Oxfam also noted "emerging epicentres" of hunger in Brazil, India, Yemen, South Africa, and the Sahel. The United Nations asked for better data in countries like Congo, North Korea, Eritrea, Kyrgyzstan, Nepal, Philippines, and Sri Lanka.

How Different Areas Were Affected

The Americas

Brazil

Oxfam called Brazil an "emerging epicentre" of hunger. About 38 million people in Brazil work in the informal economy. Most of them lost their jobs because of local lockdowns. Many favelas (slum areas) had poor water supply or no water during the pandemic. This made worries about food and water even worse. In March 2020, the Brazilian government approved a payment plan for informal workers. But groups like Caritas said it was "just about food" now, meaning people needed basic necessities.

Haiti

Haiti was an "extreme hunger" hotspot for Oxfam. Haiti had been in a recession for 1.5 years, and the price of rice had doubled since 2019. Money sent home from Haitians working abroad, called remittances, dropped. These remittances make up 20% of Haiti's economy. This drop happened because many people lost jobs in the United States and other Western countries. Half of all jobs in Haiti are in farming, which was badly hit by the pandemic. Before the pandemic, the United Nations thought 40% of Haitians would need international food aid. This number was expected to rise.

United States

Food Access Issues

After protests against police brutality and civil unrest, some cities had food shortages. This unrest can make businesses leave areas where they don't feel safe. For example, in Chicago's South Side, there were few grocery stores open because most had closed to prevent looting. In Minneapolis, during protests, some neighborhoods saw looting and damage. Lake Street became a "food desert," with few grocery stores, pharmacies, and other key businesses open. These problems were made worse by local lockdowns due to the pandemic.

Remittances from the U.S.

The United States sends the most money abroad. Money sent from workers in the U.S. to low and middle-income countries is very important for those economies. In 2019, remittances from the U.S. and other Western nations made up a large part of many countries' economies. For example, it was 37.6% for Tonga and 37.1% for Haiti.

However, the World Bank predicted that remittances would drop by nearly 20%. This means a "loss of a crucial financing lifeline for many vulnerable households." It would force many families to use their savings for food instead of education. This drop was likely due to lockdowns and the economic slowdown in Western countries. This made it harder for people to send money home. This added more stress to areas already at risk of food insecurity, especially those facing other crises.

Venezuela

Venezuela was an "extreme hunger" hotspot for Oxfam. Serious political problems and extreme food shortages led to the largest refugee crisis in the Americas. People in Venezuela and those who fled to nearby countries like Colombia and Ecuador were at high risk of not having enough food. The United Nations found that at least one-third of the people still in Venezuela didn't have enough food. These shortages got worse when the price of oil fell because of the 2020 Russia–Saudi Arabia oil price war. Many Venezuelan families had to find ways to cope, like eating less or accepting food as payment.

East Africa

East Africa is very vulnerable because of recent locust infestations. Countries like Ethiopia, Sudan, and South Sudan have been struggling with food insecurity since the 2019-20 locust infestations began in June 2019. These are "extreme hunger" hotspots. One in five people facing severe food shortages live in the Intergovernmental Authority on Development region.

Ethiopia

Ethiopia was an "extreme hunger" hotspot for Oxfam. Besides the locusts and pandemic, Ethiopia also faced problems from conflict, extreme weather, and long-lasting economic issues.

Uganda

In October 2020, statistics showed that over 400,000 refugees in Uganda were at crisis hunger levels. Another 90,000 faced extreme hunger. About 135,000 severely malnourished children needed urgent help. This was due to lockdowns and other COVID-related rules that affected people's ability to earn money. Food aid also decreased.

Europe

United Kingdom

Food banks in the UK reported a big increase in people needing help during the pandemic in 2020. This included many families who used to have average incomes but lost jobs. UNICEF also gave out food in the UK for the first time in its 70-year history.

Middle East

Syria

Syrians have faced severe food shortages because of the Syrian Civil War, which started in 2011. About 17 million people in Syria, more than half the remaining population, struggled to get enough food. Another 2.2 million were at risk. Refugees of the Syrian Civil War in neighboring Turkey and Lebanon were also at high risk. In June 2020, an international meeting raised US$5.5 billion for humanitarian help in Syria.

Yemen

Yemen is one of the countries with the worst food shortages. About 2 million children under five suffer from severe malnutrition. Groups fighting in the war have been accused of blocking food for civilians. Yemen has also been hit by locusts, a cholera outbreak, and the COVID-19 pandemic. All these disasters together have created a huge humanitarian crisis. Before the pandemic in 2019, the United Nations estimated that 20 million Yemenis had severe food insecurity. Another 10 million were at very high risk. The United Nations asked for US$2.4 billion to help prevent widespread starvation in Yemen. It was expected that more people would die from starvation than from war, cholera, and COVID-19 combined.

Sahel and West Africa

Oxfam called the West African Sahel the "fastest-growing" hunger crisis and an "extreme hunger" hotspot. About 13.4 million people there needed immediate food help. The pandemic made food insecurity worse. This was on top of problems caused by the conflict in the Maghreb and Sahel and extreme weather.

On July 23, 2020, the African Development Bank (ADB), United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and the G5 Sahel signed an agreement. Five countries in the Sahel region—Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger—were to get $20 million to help fight the COVID-19 pandemic.

Southeast Asia

Cambodia

During Cambodia's lockdown of Phnom Penh in April 2021, tens of thousands of people in the capital asked for emergency food aid. This was especially true in "red zones" where food markets were closed. The government struggled to deliver enough food in the city.

South Asia

Afghanistan

Oxfam highlighted Afghanistan as an "extreme hunger" hotspot. Between January and May 2020, 84,600 Afghans had to leave their homes because of conflict. These displaced people were at high risk of not having enough food. Also, the pandemic's effect on nearby countries meant Afghan migrants returned home. About 300,000 undocumented migrants came back from Iran, where many had lost their jobs. These returning migrants also faced food shortages. The pandemic also made it harder to deliver aid and supplies.

Bangladesh

Before the pandemic, Bangladesh already had food security problems. About 40 million people struggled to get enough food, and 11 million were severely hungry. The World Food Programme also helped 880,000 Rohingya people who fled the Rohingya genocide in Myanmar. The Prime Minister of Bangladesh, Sheikh Hasina, estimated that at least 1.1 million refugees had come into Bangladesh. Many of these refugees relied on aid for food, water, education, and shelter. The coronavirus pandemic and locust outbreaks put this aid at risk. Malnutrition, sanitation, and clean drinking water were also problems in many refugee camps. The United Nations specifically pointed out Cox's Bazar, where two large refugee camps are located.

India

Oxfam identified India as an "emerging epicentre" of hunger. About 90 million children who usually got school meals couldn't get them anymore because schools closed. It became hard to deliver food, even though India had a surplus of grain in 2019. The finance minister of Kerala state said there might be "an absolute shortage" of essential goods.

The informal sector makes up 81% of jobs in India. Many of these informal workers lost their jobs because of the lockdown. This left many unable to buy food for their families. In response, the Indian government set up "relief camps" to give shelter and food to informal and migrant workers. However, many of these camps became overwhelmed by the large number of people needing help. Getting essential services and aid into slums was also difficult because of social distancing rules. According to The Telegraph, about 90% of Indian workers are informal. They had no income during months of lockdown. In response, the government started a large program to give free food supplies to 800 million citizens.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |