Northern Ireland facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Northern Ireland

|

|

|---|---|

|

Anthem: Various

|

|

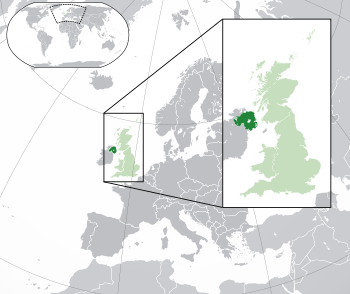

Location of Northern Ireland (dark green)

– on the European continent (green & dark grey) |

|

| Status | Country |

| Capital and largest city

|

Belfast 54°35′47″N 5°55′48″W / 54.59639°N 5.93000°W |

| Official languages |

|

| Regional and minority languages | Ulster Scots |

| Ethnic groups

(2021)

|

List

|

| Religion

(2021)

|

List

79.7% Christianity

17.4% no religion 0.6% Islam 0.2% Hinduism 0.1% Buddhism 0.0% Judaism 0.0% Sikhism 0.4% other 1.6% not stated |

|

|

| Government | Consociational devolved legislature within unitary constitutional monarchy |

|

• Monarch

|

Charles III |

| Michelle O'Neill | |

| Emma Little-Pengelly | |

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | |

| • Secretary of State | Hilary Benn |

| • House of Commons | 18 MPs (of 650) |

| Legislature | Northern Ireland Assembly |

| Devolution | |

| 3 May 1921 | |

| 18 July 1973 | |

| 17 July 1974 | |

| 19 November 1998 | |

| Area | |

|

• Total

|

14,330 km2 (5,530 sq mi) |

|

• Land

|

13,793 km2 (5,326 sq mi) |

| Population | |

|

• 2022 estimate

|

1,910,543 |

|

• 2021 census

|

1,903,175 |

|

• Density

|

141/km2 (365.2/sq mi) |

| GVA | 2022 estimate |

| • Total | £49.9 billion |

| • Per capita | £26,119 |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total

|

£56.7 billion |

|

• Per capita

|

£29,674 |

| Gini (2016–19) | low |

| HDI (2021) | very high |

| Currency | Pound sterling (GBP; £) |

| Time zone | UTC+0 (Greenwich Mean Time) |

|

• Summer (DST)

|

UTC+1 (British Summer Time) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy (AD) |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +44 |

| ISO 3166 code | GB-NIR |

|

|

Northern Ireland (Irish: Tuaisceart Éireann; Ulster Scots: Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom. It is located in the north-east of the island of Ireland. Northern Ireland shares an open border with the Republic of Ireland to its south and west.

In 2021, about 1.9 million people lived in Northern Ireland. This makes up about 3% of the UK's population. It is also about 27% of the total population on the island of Ireland. The Northern Ireland Assembly makes many of the laws for Northern Ireland. Other laws are decided by the UK Government. The government of Northern Ireland also works with the government of the Republic of Ireland on some issues.

Northern Ireland was created in 1921. This happened when Ireland was divided by a law called the Government of Ireland Act 1920. This law set up a local government for six counties in the northeast. Most people in Northern Ireland wanted to stay part of the United Kingdom. These people were often Protestant families who came from Britain a long time ago.

However, many people in the rest of Ireland, and a large group in Northern Ireland, wanted a united and independent Ireland. These people were often Catholic and saw themselves as Irish. Today, people in Northern Ireland might identify as British, Irish, or Northern Irish.

The creation of Northern Ireland led to some violence. In the 1920s, the capital city, Belfast, saw fighting between groups who wanted to stay in the UK and those who wanted a united Ireland. For the next 50 years, Northern Ireland was mostly governed by parties who wanted to stay in the UK. Some people felt that the Catholic minority was treated unfairly.

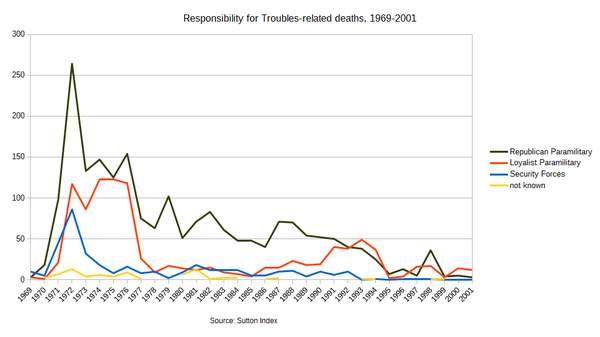

In the late 1960s, a movement started to end this unfair treatment. This led to a long period of conflict called the Troubles. This conflict lasted for about 30 years and involved armed groups and state forces. Over 3,500 lives were lost. In 1998, the Belfast Agreement (also known as the Good Friday Agreement) was signed. This was a big step towards peace. It helped disarm armed groups and brought more normal security. Even so, some social problems and occasional violence still happen.

Northern Ireland's economy was once very industrial, but it faced challenges during the Troubles. Since the late 1990s, its economy has grown a lot. Unemployment has also dropped. Northern Ireland shares culture with both the rest of Ireland and the rest of the UK. In many sports, there is one team for the whole island of Ireland. However, in football, Northern Ireland has its own team. Northern Ireland also competes separately at the Commonwealth Games. People from Northern Ireland can choose to compete for either Great Britain or Ireland at the Olympic Games.

Contents

History of Northern Ireland

The area that is now Northern Ireland was a strong point of Irish resistance against English rule in the late 1500s. The English king, Henry VIII, had claimed control of Ireland in 1542. But Irish people continued to fight back. After a major battle, many Irish leaders left the country in 1607. This allowed Protestant settlers from England and Scotland to move into the area.

In 1641, Irish leaders rebelled against English rule. This led to violence between settlers and Irish people. Later, in the late 1600s, more battles took place. English forces won, and Protestant rule became stronger in Ireland. In Northern Ireland, some Protestants still celebrate victories from these wars, like the Siege of Derry (1689) and the Battle of the Boyne (1690).

After these victories, laws were passed that treated the Catholic community unfairly. These laws also affected Presbyterians, but to a lesser extent. Because of this unfair treatment, secret groups formed in the 1700s. These groups sometimes attacked each other due to religious differences. One important event was the Battle of the Diamond. This battle led to the creation of the Orange Order, a Protestant organization.

In 1798, a rebellion started. It was led by the Society of United Irishmen, who wanted Ireland to be independent from Britain. They also wanted people of all religions to be united. After this, the governments of Great Britain and Ireland decided to join together. In 1801, they formed the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. This new country was governed from London.

Between 1717 and 1775, about 250,000 people from Ulster moved to the American colonies. Today, over 27 million people in the US are thought to have Scotch-Irish roots.

How Ireland Was Divided

During the 1800s, laws changed to remove unfair treatment against Catholics. It also became easier for farmers to buy land. By the end of the century, it seemed very likely that Ireland would get Home Rule. This meant Ireland would have more control over its own laws while still being part of the UK.

In 1912, Home Rule became almost certain. But many people in Ulster, called unionists, did not want Home Rule. They wanted to stay fully part of the United Kingdom. They even threatened to use violence. In 1914, they secretly brought in thousands of rifles for a group called the Ulster Volunteers.

Unionists were a minority in all of Ireland. But in the northern province of Ulster, they were a large majority in some counties. These counties were County Antrim and County Down. They were also small majorities in County Armagh and County Londonderry. These four counties, along with County Fermanagh and County Tyrone, later became Northern Ireland. Most of the other 26 counties were mainly nationalist.

The idea of dividing Ireland was discussed. In 1914, a Home Rule law was passed. But it was put on hold because World War I started. By the end of the war, many Irish nationalists wanted complete independence, not just Home Rule.

In 1919, a new plan was suggested. It would divide Ireland into two areas with Home Rule. One area would be 26 counties ruled from Dublin. The other would be six counties ruled from Belfast.

Ireland was officially divided in 1921. This happened during the Irish War of Independence. The war ended in December 1921 with a treaty that created the Irish Free State. Northern Ireland was given the choice to join the Free State or remain part of the UK.

Northern Ireland's Beginnings

As expected, the Parliament of Northern Ireland chose to stay part of the United Kingdom. This happened on 7 December 1922. A group was set up to decide the exact border between Northern Ireland and the Irish Free State. People in Dublin hoped that many nationalist areas would become part of the Free State. However, the group suggested only small changes to the border. To avoid arguments, the original six-county border stayed the same.

In 1940, during World War II, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill offered to push for a united Ireland. This was to encourage the neutral Irish state to join the Allies. But the Irish leader, Éamon de Valera, turned down the offer. The British government did not tell Northern Ireland's government about this offer.

In 1949, a law was passed that guaranteed Northern Ireland would stay part of the UK. This would only change if most voters in Northern Ireland agreed to it.

The Troubles Conflict

The Troubles began in the late 1960s. It was a period of intense violence that lasted about 30 years. The main reasons for the conflict were disagreements over Northern Ireland's place in the UK. There was also unfair treatment against the Irish nationalist minority by the unionist majority.

From 1967 to 1972, the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association campaigned to end unfair treatment. This included issues in housing, jobs, policing, and voting. Many unionists saw this campaign as a front for Irish republican groups. This led to more violence.

Armed groups, called paramilitaries, became involved. These included the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA), who wanted to end British rule and create a united Ireland. There was also the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), a loyalist group formed to protect Northern Ireland's British identity. The British Army and the police (the Royal Ulster Constabulary) were also part of the conflict. Some people believed that state forces worked with loyalist paramilitaries. Investigations have confirmed that some collusion did happen.

Because of the violence, Northern Ireland's local government was stopped in 1972. There was also a political stalemate between the main parties. In 1973, Northern Ireland held a vote to decide if it should stay in the UK or join a united Ireland. Most people who voted (98.9%) chose to stay in the UK. However, many Catholics did not vote.

The Peace Process

The Troubles ended with a peace process. Most armed groups declared ceasefires and gave up their weapons. The police force was reformed, and army troops were removed from the streets. This was all agreed in the Belfast Agreement (Good Friday Agreement) in 1998.

The agreement confirmed that Northern Ireland would remain in the UK unless most voters decided otherwise. The Constitution of Ireland was changed to remove its claim over all of Ireland. It now states that Ireland can only control its own territory.

The new parts of the Irish Constitution say that Northern Ireland's status can only change if most voters in both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland agree. This was a key part of the Belfast Agreement. The agreement also set up a power-sharing government in Northern Ireland. This government must include both unionist and nationalist parties.

In 2005, the Provisional IRA announced an end to its campaign. They also gave up their weapons. Other loyalist paramilitary groups also disarmed.

After elections in 2007, the local government was restored. The leaders of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Sinn Féin became First Minister and deputy First Minister. When the UK decided to leave the European Union (Brexit), the government confirmed its commitment to the Belfast Agreement. It stated that Northern Ireland's place is within the UK, but with strong links to Ireland.

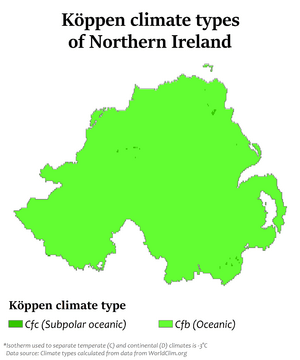

Geography and Climate

Northern Ireland was covered by a thick layer of ice during the last ice age. You can still see the effects of this in the many small hills called drumlins, especially in Counties Fermanagh, Armagh, Antrim, and Down.

The biggest lake in Northern Ireland is Lough Neagh. It is the largest freshwater lake in all of Ireland and the British Isles. Another large lake system is Lough Erne in Fermanagh. Rathlin Island is the largest island off the north Antrim coast. Strangford Lough is the largest sea inlet in the British Isles.

Northern Ireland has several mountain ranges. These include the Sperrin Mountains, the Mourne Mountains (which are made of granite), and the Antrim Plateau (made of basalt). None of the hills are very high. Slieve Donard in the Mournes is the highest point, reaching about 850 meters (2,790 feet).

The volcanic activity that formed the Antrim Plateau also created the amazing Giant's Causeway. This is a coastline with thousands of hexagon-shaped rock pillars. Other famous spots in north Antrim include the Carrick-a-Rede Rope Bridge and the Glens of Antrim.

The main rivers, like the River Bann, River Foyle, and River Blackwater, create wide, fertile lowlands. These areas are great for farming. However, much of the hill country is only good for raising animals.

The River Lagan valley is home to Belfast. The city and its surrounding areas have over a third of Northern Ireland's population. There is a lot of development along the Lagan Valley and Belfast Lough.

Northern Ireland has a mild ocean climate. It is generally wetter in the west than in the east. The weather can be unpredictable throughout the year. The seasons are clear, but not as extreme as in other parts of Europe or North America. In Belfast, the average high temperature is about 6.5°C (43.7°F) in January and 17.5°C (63.5°F) in July.

Counties of Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland is made up of six historic counties:

These counties are no longer used for local government. Instead, there are eleven districts of Northern Ireland that were created in 2015.

Even though counties are not used for government, people still use them to describe where places are. They are also used when applying for an Irish passport. The Gaelic Athletic Association still organizes its sports teams by county. Old car registration numbers are also based on counties.

The county borders can still be seen on maps. Sometimes, towns like Belfast and Lisburn are split between two counties, like Down and Antrim.

Cities and Major Towns

| Cities and towns by population | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Belfast  Derry |

# | Settlement | Population (2021) | Metro population |

Lisburn  Newry |

| 1 | Belfast | 293,298 | 639,000 | ||

| 2 | Derry | 85,279 | |||

| 3 | Greater Craigavon | 72,301 | |||

| 4 | Newtownabbey | 67,599 | |||

| 5 | Bangor | 64,596 | |||

| 6 | Lisburn | 51,447 | 84,090 | ||

| 7 | Ballymena | 31,205 | |||

| 8 | Newtownards | 29,677 | |||

| 9 | Newry | 28,530 | |||

| 10 | Carrickfergus | 28,141 | |||

People and Languages

Population of Northern Ireland

The number of people living in Northern Ireland has increased every year since 1978. In 2021, the population was 1.9 million. This was a 5% increase from ten years before. Northern Ireland's population makes up about 2.8% of the UK's total population. It is also about 27% of the population on the island of Ireland. The population density is about 135 people per square kilometer.

In 2021, almost all of Northern Ireland's population (96.6%) was white. Most people (86.5%) were born in Northern Ireland. About 4.8% were born in Great Britain, and 2.1% in the Republic of Ireland. The largest non-white groups were black (0.6%), Indian (0.5%), and Chinese (0.5%).

Identity and Citizenship

When people in Northern Ireland are asked about their national identity, they can choose more than one option. In 2021:

- 42.8% identified as British.

- 33.3% identified as Irish.

- 31.5% identified as Northern Irish.

Some people chose a mix of these identities. For example, 8.0% identified as both British and Northern Irish.

In 2021, four of the six traditional counties had more people identifying as Irish. Two counties had more people identifying as British.

Religion in Northern Ireland

In the 2011 census, 41.5% of people said they were Protestant or other non-Roman Catholic Christians. 41% identified as Roman Catholic. About 0.8% were non-Christian, and 17% had no religion or did not say. The largest Protestant groups were the Presbyterian Church (19%) and the Church of Ireland (14%).

When asked about the religion they grew up in, 48% came from a Protestant background. 45% came from a Catholic background.

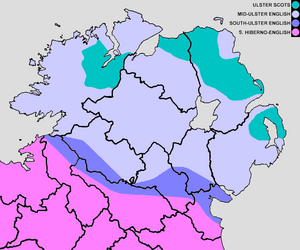

Languages Spoken

English is the main language spoken by almost everyone in Northern Ireland. It is the official language. A law from 1737 even stops other languages from being used in legal settings.

The Belfast Agreement recognizes Irish and Ulster Scots as important parts of Northern Ireland's culture. Two groups were created to promote these languages. Foras na Gaeilge promotes Irish. The Ulster-Scots Agency promotes the Ulster Scots dialect and culture.

The British government also supports these languages. Irish has more support for things like education and media. Ulster Scots has a lower level of recognition.

English Dialects

The English spoken in Northern Ireland is influenced by the Scots language. There are small differences in how Protestants and Catholics pronounce some words. For example, the letter 'h' is often pronounced differently. However, where someone lives is a much bigger factor in their accent than their religious background.

Irish Language

The Irish language (Irish: an Ghaeilge), also called Gaelic, is a native language of Ireland. It was widely spoken in Northern Ireland before the 1600s. Most place names in Northern Ireland are English versions of old Gaelic names. Today, the language is often linked to Irish nationalism and Catholics. But in the 1800s, Protestants also played a big part in bringing the language back.

In the 2011 census, 11% of people in Northern Ireland said they knew "some Irish." About 3.7% could "speak, read, write and understand" Irish.

The Irish dialect spoken in Northern Ireland is called Ulster Irish. It is very similar to Scottish Gaelic. Some words and phrases are even the same.

Using the Irish language in Northern Ireland can be a sensitive topic. Some local councils put up street signs in both English and Irish. This often happens in areas where many nationalists live. Unionists sometimes oppose this, saying it creates tension.

Ulster Scots

Ulster Scots is a variety of the Scots language spoken in Northern Ireland. It is quite easy for English speakers to understand, even if it's spoken strongly.

The Good Friday Agreement recognized Ulster Scots as part of Northern Ireland's unique culture. The St Andrews Agreement also said it was important to "develop the Ulster Scots language, heritage and culture."

About 2% of people say they speak Ulster Scots. However, very few people speak it as their main language at home. In the 2011 census, only 0.9% could speak, read, write, and understand Ulster-Scots. But 8.1% said they had "some ability" in it.

Sign Languages

The most common sign language in Northern Ireland is Northern Ireland Sign Language (NISL). However, some older deaf people from Catholic families use Irish Sign Language (ISL). This is because they used to go to schools in Dublin where ISL is common.

NISL is related to British Sign Language (BSL). ISL has some influence from French sign language. The British Government officially recognizes both BSL and ISL in Northern Ireland.

Education in Northern Ireland

Unlike most of the UK, many children in Northern Ireland take entrance exams for grammar schools in their last year of primary school. Integrated schools are becoming more popular. These schools try to have a mix of Protestant, Roman Catholic, and other students. However, most schools in Northern Ireland are still separated by religion.

In 2019, Northern Ireland had one of the youngest populations in Europe. About 21% of its population was under 16 years old.

In the 2021–2022 school year, Northern Ireland had over 1,100 schools and about 346,000 students. This included:

- 796 primary schools with 172,000 pupils.

- 192 post-primary schools with 152,000 pupils.

- 66 grammar schools with 65,000 pupils.

- 94 nursery schools with 5,800 pupils.

- 39 special schools for children with special needs.

Northern Ireland has two main universities: Queen's University Belfast and Ulster University. There is also the distance learning Open University.

Economy of Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland used to have a strong industrial economy. This included shipbuilding, making ropes, and textiles. In 2019, most of the economy (53%) came from services. The public sector made up 22%, and production was 15%.

Belfast is the UK's second largest technology hub outside of London. Over 25% of its jobs are in technology. Many big international tech companies, like Fujitsu and Microsoft, have offices there. Belfast is seen as a good place for tech workers to live because it has a lower cost of living than other cities.

In 2019, Northern Ireland welcomed 5.3 million visitors. These visitors spent over £1 billion. Tourism has grown a lot recently. Popular attractions include the Giant's Causeway and many castles. Historic towns and cities like Belfast, Derry, Armagh, and Enniskillen are also popular.

Belfast has a large shipyard that can handle some of the world's biggest ships. It has Europe's largest dry dock. The shipyard can build new ships and do maintenance work.

Northern Ireland produces enough food to feed about 10 million people, even though its own population is only 1.8 million. In 2022, most farms in Northern Ireland raised cattle and sheep. About 79% of farms had cattle, and 38% had sheep. Most farms are quite small.

Northern Ireland has a special advantage for trade. It can sell goods to the rest of the United Kingdom and the European Union without extra taxes or checks.

Here is a comparison of goods sold and bought between Northern Ireland and the United Kingdom, and between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland:

| United Kingdom | Republic of Ireland | |

|---|---|---|

| 2020 | £11.3 billion | £4.2 billion |

| 2021 | £12.8 billion | £5.2 billion |

| United Kingdom | Republic of Ireland | |

|---|---|---|

| 2020 | £13.4 billion | £2.5 billion |

| 2021 | £14.4 billion | £3.1 billion |

Transportation and Infrastructure

Northern Ireland's transport system is not as developed as some other places. Most of it is around Belfast, Derry, and Craigavon. Northern Ireland has three airports: Belfast International, George Best Belfast City, and City of Derry.

There are plans to improve the railway network. This includes new lines from Derry to Portadown and Belfast to Newry. However, these changes will take about 25 years. Major seaports are in Larne and Belfast. They carry passengers and goods between Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Passenger trains are run by NI Railways. They also work with Iarnród Éireann (Irish Rail) to provide the Enterprise service between Dublin Connolly and Belfast Grand Central. All of Ireland has a unique railway track width. This means trains are designed specifically for this system.

The Derry line is the busiest single-track railway line in the UK. It carries 3 million passengers each year. Michael Palin called the Derry-Londonderry Line "one of the most beautiful rail journeys in the world."

Main motorways include:

- M1: Connects Belfast to the south and west, ending in Dungannon.

- M2: Connects Belfast to the north. Another part of the M2 bypasses Ballymena.

Shorter motorways are:

- M12: Connects the M1 to Portadown.

- M22: Connects the M2 to near Randalstown.

- M3: Connects the M1 and M2 in Belfast with the A2 road to Bangor.

- M5: Connects Belfast to Newtownabbey.

A road connecting the ports of Larne (Northern Ireland) and Rosslare Harbour (Republic of Ireland) is being improved. This is part of an EU-funded project.

Culture of Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland shares culture with both Ulster and the United Kingdom.

More and more tourists are visiting Northern Ireland. They enjoy concert venues, cultural festivals, music, art, beautiful countryside, and friendly people. Sports like golf and fishing are also popular. Since 1987, pubs have been allowed to open on Sundays.

Parades are a very important part of Northern Ireland's society. Most are held by Protestant groups like the Orange Order. Every summer, during the "marching season," these groups have hundreds of parades. They decorate streets with British flags and light large bonfires. The biggest parades are on 12 July, known as The Twelfth. Sometimes, there is tension when these parades are near Catholic neighborhoods.

The Ulster Cycle is a collection of old stories and poems. They are about heroes from eastern Ulster around the 1st century. The main hero is Cúchulainn, who is famous for the epic story An Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of Cooley).

Symbols of Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland has different communities with different loyalties. These are often shown by flags flown from poles or lamp posts. The Union Jack (UK flag) and the old Northern Ireland flag are seen in many loyalist areas. The Irish Tricolour is flown in some republican areas. Even kerbstones are sometimes painted red-white-blue (unionist) or green-white-orange (nationalist).

The official flag of Northern Ireland is the Union Jack. The old Northern Ireland flag, called the "Ulster Banner", is no longer official since 1972. Both the Union Jack and the Ulster Banner are used by unionists.

The Saint Patrick's Saltire (a red 'X' on a white background) is used by groups like the Irish Rugby Football Union. It is also part of the flag of the United Kingdom. You might also see flags from other countries, like Palestinian flags in some nationalist areas and Israeli flags in some unionist areas.

The UK national anthem, "God Save the Queen", is often played at official events in Northern Ireland. At the Commonwealth Games, the Northern Ireland team uses the Ulster Banner flag. They use the song Londonderry Air (often known as Danny Boy) as their anthem. The Northern Ireland national football team also uses the Ulster Banner and "God Save The Queen".

Most all-Ireland sports organizations use the Irish national anthem, "Amhrán na bhFiann". Since 1995, the Ireland rugby union team has used a special song called "Ireland's Call" as its anthem.

Murals are famous features in Northern Ireland. They show past and present events and celebrate peace and different cultures. Almost 2,000 murals have been recorded since the 1970s.

Media and Communications

The BBC has a branch called BBC Northern Ireland in Belfast. It broadcasts local news and shows on BBC One and BBC Two in Northern Ireland. The ITV channel in Northern Ireland is UTV. Other UK channels like Channel 4 and Channel 5 also broadcast there. You can also get satellite and cable TV. Everyone watching live TV in Northern Ireland needs a UK TV licence.

RTÉ, the main broadcaster from the Republic of Ireland, can also be watched in most of Northern Ireland. Since digital TV started, RTÉ One, RTÉ2, and the Irish-language channel TG4 are available on Freeview in Northern Ireland.

Northern Ireland has many local radio stations, like Cool FM and Q Radio. The BBC also has two regional radio stations: BBC Radio Ulster and BBC Radio Foyle.

Besides UK and Irish national newspapers, there are three main local newspapers in Northern Ireland: the Belfast Telegraph, The Irish News, and The News Letter.

Northern Ireland uses the same phone and postal services as the rest of the UK. Calls to the Republic of Ireland from Northern Ireland landlines are charged at the same rate as calls within the UK.

Sports in Northern Ireland

Many sports in Ireland are organized for the whole island. This means there is one governing body or team for both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. The main exception is football (soccer). Football has a separate governing body, league, and national team for Northern Ireland.

The Irish Football Association (IFA) runs men's football in Northern Ireland. The NIWFA does the same for women's football. The NIFL Premiership is the top men's football league. The winner can enter the UEFA Champions League. The NLFL Women's Premiership is the top women's league.

The men's Northern Ireland national football team has played in the FIFA World Cup three times (1958, 1982, 1986). They also reached the knockout stage of the European Championships in 2016.

The IRFU governs rugby union for the whole island of Ireland. Rugby in Northern Ireland is part of the Ulster province, which also includes three counties from the Republic of Ireland.

The Ireland cricket team represents both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. It is a full member of the International Cricket Council. This means it can play Test cricket, the highest level of the sport. The men's team has played in the Cricket World Cup and T20 World Cup. The women's team has played in the Women's World Cup. One of their home grounds is Stormont in Belfast.

Golf Ireland is the governing body for golf on the island. Northern Ireland has famous golf courses, like Royal Portrush Golf Club. This is the only course outside Great Britain to have hosted The Open Championship. Royal County Down Golf Club is also highly rated. Northern Ireland has produced several major golf champions, including Graeme McDowell, Rory McIlroy, and Darren Clarke.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Irlanda del Norte para niños

In Spanish: Irlanda del Norte para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |