History of the Grand Canyon area facts for kids

The known human history of the Grand Canyon area goes back about 10,500 years. That's when the first signs of people living there were found. Native Americans have called the Grand Canyon home for at least the last 4,000 years.

Ancient groups like the Ancestral Puebloans started as hunter-gatherers. Over time, they learned to farm more and settled down. Another group, the Cochimi, also lived in the canyon. A big drought in the late 1200s likely made both groups move away. Later, other tribes like the Paiute, Cerbat, and Navajo arrived. Sadly, the United States Government later forced them onto reservations.

In 1540, a Spanish explorer named Francisco Vázquez de Coronado sent Captain García López de Cárdenas to find the legendary Seven Cities of Gold. Cárdenas and his soldiers, with Hopi guides, became the first Europeans to see the Grand Canyon. It took over 200 years for more non-Native Americans to visit.

In 1869, U.S. Army Major John Wesley Powell led an expedition down the Colorado River through the canyon. His journey and later studies by geologists helped us understand the amazing geology of the Grand Canyon area. In the late 1800s, people became interested in mining copper and asbestos there. The first pioneer settlements started in the 1880s.

Soon, people realized that tourism would bring more money than mining. By the early 1900s, the Grand Canyon was a popular tourist spot. Most visitors traveled by stagecoach from nearby towns to the South Rim. In 1901, the Grand Canyon Railway opened, connecting Williams, Arizona, to the South Rim. This led to many new tourist facilities, especially at Grand Canyon Village.

The Fred Harvey Company built famous places like the luxury El Tovar Hotel in 1905 and Phantom Ranch in 1922. The Grand Canyon was first protected as a forest reserve in 1893. Then it became a U.S. National Monument in 1908. But it didn't become a U.S. National Park until 1919. Today, Grand Canyon National Park welcomes about five million visitors every year. This is a huge jump from the 44,173 visitors in 1919.

Contents

Early Human History in the Grand Canyon

Archaeologists believe humans lived in the Grand Canyon area as far back as 4,000 years ago. They might have passed through for 6,500 years before that. Scientists used Radiocarbon dating on old items found in caves. These items, like small animal figurines made from twigs, are 3,000 to 4,000 years old. These figurines are only a few inches tall. They are made from willow or cottonwood twigs. This suggests early canyon dwellers were part of the Desert Culture. They were semi-nomadic Native American hunter-gatherers.

The Ancestral Puebloans (also called Histatsinom, meaning "people who lived long ago") developed from the Desert Culture around 500 BCE. They lived on the canyon rim and inside the canyon. They survived by hunting and gathering, and also did some farming. They were known for their basket-making skills. They lived in small groups in caves and round mud homes called pithouses.

Around 500 CE, the Ancestral Puebloans improved their farming and tools. This led to a more settled lifestyle. At the same time, another group called the Cohonina lived west of Grand Canyon Village.

Around 800 CE, Ancestral Puebloans in the Grand Canyon started building houses above ground. They used stone along with mud and poles. This began the Pueblo period of their culture. In summer, they moved from the hot inner canyon to cooler high plateaus. They returned to the canyon for winter. Large storage buildings and multi-room pueblos from this time still exist. There are about 2,000 known Ancestral Pueblo archaeological sites in the park. The easiest one to visit is Tusayan Pueblo. It was built around 1185 and housed about 30 people.

Many archaeological sites show that the Ancestral Pueblo and Cohonina groups thrived until about 1200 CE. But something happened about 100 years later. Both cultures were forced to move away. Evidence suggests that climate change caused a severe drought from 1276 to 1299. This drought forced these farming cultures to leave. Many Ancestral Puebloans moved to the Rio Grande and Little Colorado River areas. Their descendants, the Hopi and the 19 Pueblos of New Mexico, live there today.

For about 100 years, the canyon area was empty of people. Then, Paiute from the east and Cerbat from the west were the first to settle there again. The Paiute settled north of the Colorado River. The Cerbat built their homes south of the river, on the Coconino Plateau. The Navajo, or Diné, arrived later.

These three cultures were stable until the United States Army moved them to Indian reservations in 1882. This was part of efforts to end the Indian Wars. The Havasupai and Hualapai tribes are descendants of the Cerbat. They still live in the area. The village of Supai in the western part of the park has been lived in for centuries. Next to the eastern part of the park is the Navajo Nation. It is the largest reservation in the United States.

European Explorers Discover the Grand Canyon

Spanish Explorers Arrive

The first Europeans to see the Grand Canyon arrived in September 1540. It was a group of about 13 Spanish soldiers. They were led by García López de Cárdenas. He was sent by Francisco Vázquez de Coronado to find the famous Seven Cities of Gold. Hopi guides led the group. They likely reached the South Rim, perhaps between today's Desert View and Moran Point.

The explorers greatly misjudged the canyon's size. They thought it was about 8 to 10 miles wide, which was quite accurate. But they believed the river below was only 6 feet wide! In reality, it's about 100 times wider. They desperately needed water and wanted to cross. So, the soldiers searched for a way down that their horses could use. After three days, they still hadn't found a path. It's thought the Hopi, who probably knew a way, didn't want to show them.

As a last try, Cárdenas sent three light and agile men to climb down. Their names were Pablo de Melgosa, Juan Galeras, and another soldier. After several hours, they returned. They reported they had only gone a third of the way down. They said "what seemed easy from above was not so." They also claimed that some boulders they saw from the rim, which looked man-sized, were actually taller than the Great Tower of Seville (over 340 feet). Cárdenas had to give up. His report of an impassable barrier stopped others from visiting for 200 years.

In 1776, two Spanish priests, Fathers Francisco Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, traveled along the North Rim. They were exploring southern Utah, looking for a route from Santa Fe, New Mexico to Monterey, California. Also in 1776, a missionary named Fray Francisco Garces spent a week near Havasupai. He tried to convert Native Americans but was unsuccessful. He described the canyon as "profound."

American Explorers and Scientists

James Ohio Pattie and a group of American trappers were likely the next Europeans to reach the canyon in 1826. However, there isn't much proof of their visit.

After the Mexican–American War ended in 1848, the Grand Canyon became part of the United States. Jules Marcou made the first geological observations of the canyon in 1856.

Jacob Hamblin, a Mormon missionary, was sent in the 1850s to find easy river crossing spots. He built good relationships with local Native Americans and settlers. He found Lee's Ferry in 1858 and Pierce Ferry. These were the only two good spots for ferry operations.

In 1857, Edward Fitzgerald Beale led an expedition. They were surveying a wagon road from Fort Defiance, Arizona to the Colorado River. On September 19, near today's National Canyon, they found a "wonderful canyon four thousand feet deep." Everyone in the group agreed they had never seen anything like it.

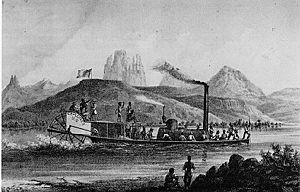

The United States Department of War sent an expedition led by Joseph Christmas Ives in 1857. They wanted to find natural resources, railroad routes to the west coast, and see if boats could travel up the river from the Gulf of California. The group used a steamboat called Explorer. After two months and 350 miles of tough travel, they reached Black Canyon. The Explorer hit a rock and was left behind. The group then traveled east along the South Rim of the Grand Canyon.

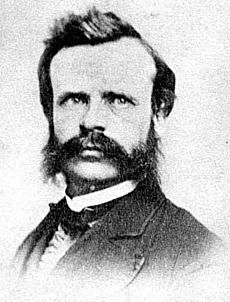

Ives didn't think much of the canyon's beauty. He called it "altogether valueless." He even said his expedition would be "the last party of whites to visit this profitless locality." But John Strong Newberry, a geologist with Ives, had a different view. Newberry convinced another geologist, John Wesley Powell, that a boat trip through the Grand Canyon would be worth the risk. Powell was a major in the United States Army. He lost his right arm in the American Civil War.

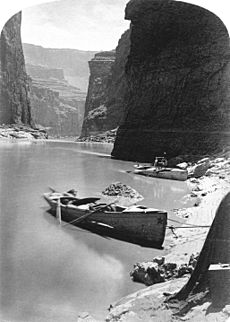

More than ten years after Ives' trip, Powell led the first of his expeditions. He wanted to explore the region and study its science. On May 24, 1869, nine men set out from Wyoming. They went down the Colorado River and through the Grand Canyon. This first trip didn't have much money. So, there was no photographer or artist. One of their four boats flipped over in the Canyon of Lodore. They lost most of their food and scientific gear. This made the trip shorter, lasting only 100 days.

Three of Powell's men got tired of being cold, wet, and hungry. They didn't know they had passed the worst rapids. They climbed out of the canyon in what is now called Separation Canyon. All three were reportedly killed by the Shivwits band of Paiute. Everyone who stayed with Powell survived. They successfully traveled through most of the canyon.

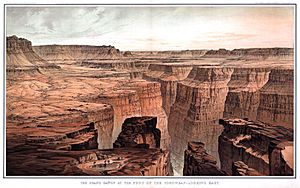

Two years later, Powell led a second, better-funded trip. They had new boats and supply stations along the way. This time, photographer E.O. Beaman and 17-year-old artist Frederick Dellenbaugh joined. Beaman left in 1872. His replacement, James Fennemore, quit due to poor health. This left boatman John Karl Hillers as the official photographer. They needed nearly a ton of camera equipment to process each photo! Famous painter Thomas Moran joined in 1873, after the river trip. He only saw the canyon from the rim. His 1873 painting "Chasm of the Colorado" was bought by the United States Congress. It hung in the lobby of the Senate.

The Powell expeditions carefully recorded rock formations, plants, animals, and ancient sites. Photos and drawings from these trips made the canyonlands of the southwest United States very popular. Powell used these images in his lectures, making him a national figure. Rights to reproduce 650 of the expeditions' 1,400 stereographs were sold to help fund future projects. In 1881, Powell became the second director of the U.S. Geological Survey.

Geologist Clarence Dutton continued Powell's work in 1880–1881. He did the first detailed geological survey for the new U.S. Geological Survey. Painters Thomas Moran and William Henry Holmes joined Dutton. Dutton wrote detailed descriptions of the area's geology. Their report, A Tertiary History of The Grand Canyon District, with Atlas, was published in 1882. This and later studies helped advance the science of geology. Both the Powell and Dutton expeditions made more people interested in the canyon.

The Brown-Stanton expedition started in 1889. They wanted to find a route for a "water-level" railroad through the Colorado River canyons. This railroad would carry coal from Colorado. Expedition leader Frank M. Brown, his engineer Robert Brewster Stanton, and 14 others set out in six boats. Brown and two others drowned near Marble Canyon. Stanton restarted the expedition. They reached the Gulf of California in 1890, but the railroad was never built.

In the 1870s and 1880s, prospectors claimed mining sites in the canyon. They hoped to profit from asbestos, copper, lead, and zinc. But it was too hard to get to this remote area and transport the ore out. Most miners left. Some stayed to make money from tourists. Their work did improve old Indian trails, like the Bright Angel Trail.

Grand Canyon Tourism Develops

Getting to the Canyon

A train line to Flagstaff, the largest city nearby, was finished in 1882. This was built by the Santa Fe Railroad. The next year, stagecoaches started bringing tourists from Flagstaff to the Grand Canyon. This was an eleven-hour trip. Travel became much easier in 1901. A new train line from the Santa Fe Railroad reached Grand Canyon Village. The first train with paying passengers arrived from Williams, Arizona, on September 17 that year. The 64-mile trip cost $3.95. Naturalist John Muir praised the railroad for its small impact on nature.

The first car was driven to the Grand Canyon in January 1902. Oliver Lippincott from Los Angeles drove his steam car from Flagstaff to the South Rim. Lippincott, a guide, and two writers started their trip on January 2. They expected a seven-hour journey. Two days later, hungry and thirsty, they arrived. The land was too rough for the ten-horsepower car. Winfield Hoggaboon, one of the writers, wrote a funny story about the trip. In 1907, it took a three-day drive from Utah to reach the North Rim for the first time.

Cars became more popular, and the Santa Fe Railroad stopped the Grand Canyon Railway in 1968. Only three passengers were on the last trip. The railway was fixed and reopened in 1989. Since then, it carries hundreds of passengers daily. Trains were the main way to travel to the canyon until cars took over in the 1930s. By the early 1990s, over a million cars visited the park each year.

West Rim Drive was finished in 1912. In the late 1920s, the first way to cross from rim to rim was built. This was the North Kaibab suspension bridge over the Colorado River. Paved roads didn't reach the less popular North Rim until 1926. That area is higher up, so it closes from November to April due to winter weather. A road along part of the South Rim was completed in 1935.

Air Pollution Concerns

Cars are a main source of the Grand Canyon's haze. Their emissions are regulated by federal, state, and local rules. The Grand Canyon Visibility Transport Commission says that car emissions and gas standards, which change slowly, contribute to air quality problems. They suggest stricter emission rules and cleaner fuel.

Air pollution from cars and wind-blown pollution from Las Vegas, Nevada, has reduced visibility. In the past decade, coal-fired power plants with little pollution control were blamed. In the 1980s, the Navajo Generating Station (15 miles away) was identified as a major source. It caused 50% to 90% of the canyon's air quality issues. In 1999, the Mohave Generating Station (75 miles away) agreed to install pollution scrubbers.

Closer to home, the park's popularity causes many visibility problems. On a summer day, the park is often full or over capacity. Too many private cars compete for too few parking spots. Emissions from these cars and tour buses greatly add to air pollution.

Places to Stay and Visit

John D. Lee was the first person to offer services to canyon travelers. In 1872, he started a ferry service where the Colorado and Paria rivers meet. Lee was in hiding because he was accused of leading the Mountain Meadows Massacre in 1857. He was tried and executed for this in 1877. During his trial, he hosted members of the Powell Expedition. Emma, one of Lee's nineteen wives, continued the ferry business after his death. In 1876, Harrison Pierce started another ferry service at the western end of the canyon.

The two-room Farlee Hotel opened in 1884 near Diamond Creek. It operated until 1889. That year, Louis Boucher opened a larger hotel at Dripping Springs. John Hance opened his ranch near Grandview to tourists in 1886. Nine years later, he sold it to become a Grand Canyon guide. In 1896, he also became the local postmaster.

William Wallace Bass opened a tent campground in 1890. Bass Camp had a small main building with a kitchen, dining room, and sitting room. Rates were $2.50 a day. The camp was 20 miles west of the Grand Canyon Railway's Bass Station. Bass also built the stagecoach road to carry his guests from the train station to his hotel. A second Bass Camp was built along the Shinumo Creek drainage.

The Grand Canyon Hotel Company was formed in 1892. Its job was to build services along the stage route to the canyon. In 1896, the same man who bought Hance's Grandview ranch opened Bright Angel Hotel in Grand Canyon Village. The Cameron Hotel opened in 1903. Its owner started charging a toll to use the Bright Angel Trail.

Things changed in 1905 when the luxury El Tovar Hotel opened. It was right next to the Grand Canyon Railway's end point. El Tovar was named after Don Pedro de Tovar. Tradition says he was the Spaniard who learned about the canyon from the Hopis and told Coronado. Charles Whittlesey designed the Arts and Crafts-style hotel. It was built with logs from Oregon and local stone. The hotel cost $250,000, and the stables cost another $50,000. El Tovar was owned by the Santa Fe Railroad. It was run by their main partner, the Fred Harvey Company.

Fred Harvey hired Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter in 1902 as the company architect. She designed five buildings at the Grand Canyon: Hopi House (1905), Lookout Studio (1914), Hermit's Rest (1914), Desert View Watchtower (1932), and Bright Angel Lodge (1935). She stayed with the company until she retired in 1948.

A cable car system across the Colorado River started at Rust's Camp in 1907. This camp was near the mouth of Bright Angel Creek. Former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt stayed at the camp in 1913. He also declared the Grand Canyon a U.S. National Monument in 1908. Because of this, the camp was renamed Roosevelt's Camp. In 1922, the National Park Service gave it its current name, Phantom Ranch.

In 1917, W.W. Wylie built places to stay at Bright Angel Point on the North Rim. The Grand Canyon Lodge opened on the North Rim in 1928. It was built by a company related to the Union Pacific Railroad. The lodge was designed by Gilbert Stanley Underwood, who also designed the Ahwahnee Hotel in California's Yosemite Valley. Much of the lodge was destroyed by fire in 1932. A rebuilt lodge opened in 1937. The Bright Angel Lodge and the Auto Camp Lodge opened in 1935 on the South Rim.

Fun Activities at the Canyon

New hiking trails, often following old Indian paths, were created. The famous mule rides down Bright Angel Trail were heavily promoted by the El Tovar Hotel. By the early 1990s, 20,000 people rode mules into the canyon each year. 800,000 hiked, 22,000 rafted through, and 700,000 flew over in air tours. Overflights were limited in 1956 after two planes crashed, killing everyone on board. In 1991, nearly 400 search and rescue missions happened. Most were for hikers who got heat exhaustion and dehydration while climbing out. An IMAX theater outside the park shows a film about the Powell Expedition.

The Kolb Brothers, Emery and Ellsworth, built a photo studio on the South Rim in 1904. It was at the start of the Bright Angel Trail. Hikers and mule groups going into the canyon would stop there for photos. The Kolb Brothers would print the pictures before their customers returned to the rim. In 1911–12, they used a new camera to make the first motion picture of a river trip through the canyon. This was only the eighth successful river journey. From 1915 to 1975, they showed their film twice a day to tourists. Emery Kolb would narrate it himself.

Protecting the Grand Canyon

By the late 1800s, the conservation movement grew. People wanted to protect natural wonders like the Grand Canyon. National Parks like Yellowstone and Yosemite Valley were created by the early 1890s. U.S. Senator Benjamin Harrison tried to make the Grand Canyon a national park in 1887. The bill didn't pass. But on February 20, 1893, Harrison, who was then President, declared the Grand Canyon a National Forest Preserve. Mining and logging were still allowed, but it offered some protection.

President Theodore Roosevelt visited the Grand Canyon in 1903. He loved the outdoors and was a strong conservationist. He created the Grand Canyon Game Preserve on November 28, 1906. This reduced grazing by livestock. But predators like mountain lions, eagles, and wolves were killed off. Roosevelt added nearby national forest lands. He then renamed the preserve a U.S. National Monument on January 11, 1908.

People who owned land and mining claims fought against making it a National Park for 11 years. Finally, Grand Canyon National Park was established as the 17th U.S. National Park. President Woodrow Wilson signed the law on February 26, 1919. The National Park Service made the Fred Harvey Company the official park concessionaire in 1920. They also bought out William Wallace Bass's business.

An area of almost 310 square miles next to the park became a second Grand Canyon National Monument on December 22, 1932. Marble Canyon National Monument was created on January 20, 1969. It covered about 41 square miles. On January 3, 1975, President Gerald Ford signed a law that doubled the size of Grand Canyon National Park. It combined these monuments and other federal land into the park. That same law gave Havasu Canyon back to the Havasupai tribe. From then on, the park stretched about 278 miles along the Colorado River. It went from the southern border of Glen Canyon National Recreation Area to the eastern edge of Lake Mead National Recreation Area. Grand Canyon National Park was named a World Heritage Site on October 24, 1979.

In 1935, Hoover Dam started to create Lake Mead south of the canyon. Conservationists lost a fight to save Glen Canyon upstream from becoming a reservoir. The Glen Canyon Dam was finished in 1966. It was built to control floods and provide water and hydroelectric power. Before, the river had high flows in spring and low flows in summer. Now, it's much more controlled. The clearer water has less sediment, which means fewer beaches and sand bars. Also, clearer water allows more algae to grow on the riverbed, making the river look green.

With commercial flights, flying over the Grand Canyon became popular. But several accidents led to the Overflights Act of 1987 by the United States Congress. This law banned flights below the rim and created flight-free zones. Tourist flights also caused a noise problem. So, the number of flights over the park has been limited.

In 2008, the Grand Canyon Railway decided to use only diesel locomotives. They felt their steam locomotives and other older engines created too much visible smoke. Steamers also burned more oil and were more expensive to run. However, after many train fans protested, the railway brought back steam operations. They changed their two working steamers to burn recycled waste vegetable oil. This oil is collected from nearby restaurants by other companies.

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |