History of timekeeping devices facts for kids

The story of how we measure time goes way back! Ancient people first started watching the Sun, Moon, and stars as they moved across the sky. Over time, people invented better and better ways to keep track of hours, minutes, and seconds.

At first, they used things that moved continuously, like water flowing in water clocks. Then came mechanical clocks, and later, devices that used repetitive, swinging motions, like pendulums. Today, modern timepieces still use these swinging parts to be super accurate.

Sundials and water clocks were first used in ancient Egypt around 1200 BC. Later, the Babylonians, Greeks, and Chinese also used them. Incense clocks appeared in China by the 6th century. In the Middle Ages, Islamic water clocks were very advanced until the mid-1300s. The hourglass, invented in Europe, was one of the best ways to measure time on ships at sea.

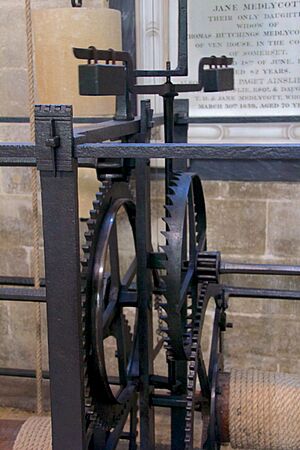

In medieval Europe, mechanical clocks were developed. They started with a bell-striking alarm to tell monks when to ring their bells. These early clocks used weights to power them, controlled by a special part called a verge and foliot. This was a huge step forward! A famous mechanical clock was built by Henry de Vick around 1360, and its basic design was used for the next 300 years. Later, the mainspring was invented in the early 1400s, which meant small clocks could be made for the first time.

A big improvement in clock making came in the 1600s. People discovered that clocks could be controlled by things that swing back and forth regularly, called harmonic oscillators. Leonardo da Vinci drew pendulums in the late 1400s. In 1582, Galileo Galilei studied how pendulums swing. He found that how fast a pendulum swings only depends on its length, not its weight.

The pendulum clock, designed by Christiaan Huygens in 1656, was much more accurate than older mechanical clocks. Because of this, very few of the old verge and foliot clocks survived. Other cool inventions from this time included clocks that struck the hours, repeating clocks (which could chime the time on demand), and the deadbeat escapement, which made clocks even more precise.

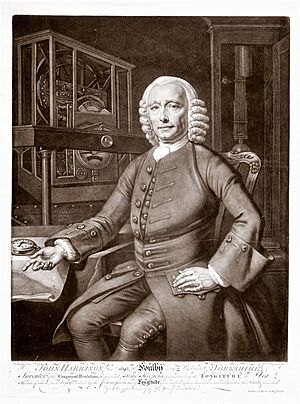

Early pendulum clocks had problems with temperature changes. In the 1700s, English clockmakers John Harrison and George Graham worked on this. After a big naval disaster in 1707, the government offered a huge prize to anyone who could figure out how to find a ship's longitude (its east-west position). Harrison built super accurate timepieces, calling them chronometers.

The electric clock, invented in 1840, helped control the most accurate pendulum clocks until the 1940s. Then, quartz timers became the best way to measure time precisely.

The wristwatch became popular after World War I. It was seen as a useful tool during the Boer War. Later versions included non-magnetic, battery-powered, and solar-powered watches, with quartz, transistors, and plastic parts. Since the early 2010s, smartphones and smartwatches have become the most common ways people tell time.

Today, the most accurate timekeeping devices are atomic clocks. They can be accurate to a few billionths of a second per year! These clocks are used to check and set all other clocks and timekeeping tools.

Contents

Early Ways to Tell Time

Ancient people watched the Sun and Moon to figure out the time. For example, Stonehenge in England might have been like an ancient observatory. People probably used it to mark important events like the equinoxes (when day and night are equal) and solstices (the longest and shortest days). We don't know much about how these very old civilizations kept time because they didn't write things down.

People in Mesoamerica (like the Maya) changed their counting system to create a 360-day year for their calendars. Aboriginal Australians were also very good at understanding the sky. They used their knowledge to make calendars and help them navigate. Most Aboriginal cultures had clear seasons based on natural changes and sky events. They used phases of the Moon to mark shorter periods. Some groups, like the Yaraldi in South Australia, even divided the day into seven parts using the Sun's position.

Before the 1200s, all timekeepers used things that moved constantly. But none of these early methods changed at a perfectly steady rate. Timekeeping devices have gotten better and better through many new inventions.

Shadow Clocks and Sundials

The first tools for measuring the Sun's position were shadow clocks. These later became the sundial. The oldest known sundial was found in Egypt in 2013. It dates back to about 1200 BC. Tall stone pillars called obelisks could show if it was morning or afternoon, and also the summer and winter solstices. Around 500 BC, a T-shaped shadow clock was developed. It measured time by the shadow its crossbar made. People would turn it around at noon to keep tracking the shadow.

The Bible mentions a sundial in 2 Kings 20:9–11. King Hezekiah of Judea (around 8th century BC) was healed by the prophet Isaiah. Hezekiah asked for a sign that he would recover. Isaiah made the shadow on the sundial go back ten steps!

A clay tablet from ancient Babylonia describes how long shadows were at different times of the year. The Greek writer Berossos (around 3rd century BC) is said to have invented a bowl-shaped sundial carved from stone. The shadow's path was divided into 12 parts to mark the time. Greek sundials became very advanced. Ptolemy's Analemma, written in the 2nd century AD, used early trigonometry to figure out the Sun's position based on the time of day and location.

The Romans learned about sundials from the Greeks. The first sundial in Rome arrived in 264 BC. It divided the day into hours, which was new for Romans who used to just split the day into morning and afternoon. However, this sundial was wrong for a century because it wasn't set for Rome's latitude! It was finally fixed in 164 BC.

Historian Ernst Zinner says that by the 1200s, sundials had scales that showed equal hours. The first sundial based on "polar time" appeared in Germany around 1400.

An Egyptian way to tell time at night, used from at least 600 BC, was a tool called a merkhet. They would line up two merkhets with Polaris, the North Star. Then, they watched specific stars as they crossed this line to tell the time.

The Jantar Mantar in Jaipur, India, built in 1727, has a huge sundial called the Vrihat Samrat Yantra. It's 88 feet (27 m) tall and can tell the local time to within about two seconds!

Water Clocks

The oldest description of a water clock, or clepsydra, is from an Egyptian official named Amenemhet around 1500 BC. He is thought to be its inventor. It was probably a bowl with marks to show the time. The oldest water clock that still exists was found in the tomb of pharaoh Amenhotep III (around 1417–1379 BC). We don't have any surviving water clocks from ancient Mesopotamia, but we know they existed from written records.

Water clocks came to China, possibly from Mesopotamia, as early as the 2nd millennium BC. Around 550 AD, Yin Kui was the first in China to write about overflow tanks for water clocks. Around 610, two inventors created the first balance clepsydra. In 721, the mathematician Yi Xing and official Liang Lingzan controlled the power of water in an astronomical clock. This allowed them to copy the movements of planets and stars. In 976, the astronomer Zhang Sixun solved the problem of water freezing in clepsydrae by using liquid mercury instead of water. In 1088, Su Song built a water-powered astronomical clock tower that had the first known endless chain drive to transmit power.

Greek thinkers like Anaxagoras and Empedocles mentioned water clocks being used to set time limits or measure time passing. The philosopher Plato is said to have invented an alarm clock that used lead balls dropping onto a copper plate to wake his students!

A problem with most water clocks was that the water flow changed as the pressure changed. This was fixed around 100 BC when the water container was made into a cone shape. Water clocks became more complex, adding gongs and moving parts. There's good evidence that the Tower of the Winds in Athens (1st century BC) once had a water clock, a wind vane, and nine sundials. In Greece, water clocks were used in courts, a practice later adopted by the Ancient Romans.

In medieval Al-Andalus (Islamic Spain), Ibn Khalaf al-Muradi described a water clock with complex gears. Islamic water clocks were very advanced, with many moving figures, and were the best until the mid-1300s. Some people believe the first geared clock was invented by Archimedes in the 3rd century BC. He supposedly made an astronomical clock that was also a cuckoo clock, playing music and having birds move every hour!

The 12th-century Jayrun Water Clock in Damascus was built by Muhammad al-Sa'ati. His son later described it in a book. A very complex water-powered astronomical clock was described by Al-Jazari in 1206. This "castle clock" was about 11 feet (3.4 m) high. In 1235, a water-powered clock in Baghdad announced prayer times day and night.

Chinese Incense Clocks

Incense clocks were first used in China around the 6th century. They were mainly for religious ceremonies, but also for social gatherings or by scholars. Some experts think they might have been invented in India. Incense burns slowly and without a flame, so these clocks were safe to use indoors. To mark different hours, they used incense with different smells.

The incense sticks could be straight or spiral-shaped. The spiral ones were for longer periods and often hung from roofs. Some clocks were designed to drop small weights at regular times.

Incense seal clocks had a disk with grooves carved into it. Incense was placed in these grooves. The length of the incense path determined how long the clock would last. To burn for 12 hours, an incense path of about 20 meters (65 feet) was needed! Later, metal disks were used, especially during the Song dynasty. This made it easier to create different sizes and designs, and to change the path of the grooves to account for the changing length of days throughout the year. As smaller seals became available, incense seal clocks became popular gifts.

Astrolabes

Very advanced astrolabes with gears were made in Persia. For example, Abū Rayhān Bīrūnī built one in the 11th century, and Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr al‐Farisi built one around 1221. A brass and silver astrolabe made by al-Farisi is the oldest surviving machine with its gears still working. It also acted as a calendar. Openings on the back showed the lunar phases and the Moon's age. Inside, rings showed the positions of the Sun and Moon.

Muslim astronomers built many very accurate astronomical clocks for their mosques and observatories. One example is the astrolabic clock by Ibn al-Shatir in the early 1300s.

Candle Clocks and Hourglasses

One of the first mentions of a candle clock is in a Chinese poem from 520 AD. It talks about a candle with marks on it to tell time at night. Similar candles were used in Japan until the early 900s.

The invention of the candle clock is sometimes credited to Alfred the Great, king of Wessex (871–889). He supposedly used six candles, each marked at 1-inch (2.5 cm) intervals. Each candle was about 12 cm (4.7 in) tall and made from a specific amount of wax.

In the 12th century, the Muslim inventor Al-Jazari described four different candle clock designs in his book. His "scribe" candle clock was made to mark 14 hours of equal length. A precise mechanism slowly pushed a candle upwards, which moved an indicator along a scale.

The hourglass was one of the few reliable ways to measure time at sea. Some think it was used on ships as early as the 1000s, helping sailors with navigation alongside the compass. The first clear picture of an hourglass is in the painting Allegory of Good Government by Italian artist Ambrogio Lorenzetti, from 1338.

The Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan used 18 hourglasses on each ship during his trip around the world in 1522. Although hourglasses were used in China, their history there isn't well known. They probably weren't used before the mid-1500s, as making hourglasses required glassblowing, which was mostly a European skill then.

From the 1400s onwards, hourglasses were used in many places: at sea, in churches, in factories, and for cooking. They were the first reliable, reusable, fairly accurate, and easy-to-make time-measuring devices. The hourglass also became a symbol for things like death, patience, opportunity, and Father Time.

How Clocks Started to Swing and Tick

The English word clock first appeared in the Middle Ages. It might come from French or Dutch words related to "bell." In the 600s and 800s, "clock" meant "bell" in Irish and German languages.

Many religions, like Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, had set times for prayer. Christians especially had strict times for prayers throughout the day and night. Bell-striking alarms were used to tell monks when to ring the monastic bell. This alarm used an early form of escapement to ring a small bell. This mechanism was a very early version of the escapement found in mechanical clocks.

1200s

The first attempts to make hourglasses and water clocks more accurate happened in the 900s. People tried to slow their flow using friction or gravity. The earliest picture of a clock powered by a hanging weight is from a book called the Bible of St Louis, made between 1226 and 1234. It shows a clock being slowed by water acting on a wheel. This suggests that weight-driven clocks were invented in Western Europe. A writing from 1271 by Robertus Anglicus shows that medieval craftspeople were trying to design a purely mechanical clock (powered only by gravity). These clocks combined ideas from European and Islamic science, like gears, weight drives, and striking mechanisms.

In 1250, the artist Villard de Honnecourt drew a device that was a step towards the escapement. Another early version of the escapement was the horologia nocturna. It used an early verge mechanism to make a knocker continuously hit a bell. The weight-driven clock was probably a Western European invention. In 1271, the English astronomer Robertus Anglicus wrote that his friends were working on a mechanical clock.

1300s

The invention of the verge and foliot escapement around 1275 was one of the most important inventions in the history of clocks and technology. It was the first type of regulator in clockmaking. A vertical shaft, or verge, is forced to turn by a weight-driven crown wheel. But a foliot stops it from spinning freely. The foliot swings back and forth, letting the wheel turn one tooth at a time. Even though the verge and foliot was an improvement, it wasn't perfect. Early mechanical clocks often had to be reset using a sundial.

Around the same time, the poet Dante Alighieri used clock images in his poem Paradiso, written in the early 1300s. This might be the first time a mechanical clock was described in literature. We find mentions of house clocks from 1314 onwards. By 1325, mechanical clocks were probably well-developed.

Large mechanical clocks were built and placed in towers to ring bells directly. The tower clock of Norwich Cathedral, built around 1273, is the earliest known large clock of this type, though it no longer exists. The first clock known to strike regularly on the hour was recorded in Milan in 1336. By 1341, weight-driven clocks were common enough to be used in grain mills. By 1344, the clock in London's Old St Paul's Cathedral was replaced with one that had an escapement.

The most famous clock of the medieval period was designed by Henry de Vick around 1360. It was said to be off by up to two hours a day! But for the next 300 years, all clock improvements were based on de Vick's design. Between 1348 and 1364, Giovanni Dondi dell'Orologio built a complex astrarium (a kind of astronomical clock) in Florence.

In the 1300s, striking clocks became more common in public places. They first appeared in Italy, then France and England. Between 1371 and 1380, over 70 European cities got public clocks. The Salisbury Cathedral clock, from about 1386, is one of the oldest working clocks in the world. It still has most of its original parts. The Wells Cathedral clock, built in 1392, is special because it still has its original medieval face. Above the clock, figures hit the bells, and jousting knights spin around a track every 15 minutes.

Later Developments

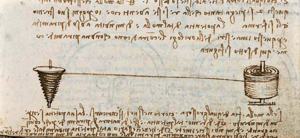

The invention of the mainspring in the early 1400s allowed small clocks to be built for the first time. This spring was first used in locks and guns. To control the energy released by the spring, two devices were developed: the stackfreed (around 1535) and the fusee. The fusee came from medieval weapons like the crossbow. The earliest surviving spring-driven clock, made for Philip the Good around 1430, has a fusee. Leonardo da Vinci drew a fusee around 1500, about 25 years after the coiled spring first appeared.

Clock towers in Western Europe struck the time in the Middle Ages. Early clock faces showed hours. A clock with a minutes dial was mentioned in a manuscript from 1475. In the 1500s, timekeepers became more refined. By 1577, the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe got the first of four clocks that measured in seconds. In Nuremberg, Germany, clockmaker Peter Henlein was paid for making what is thought to be the earliest watch in 1524. By 1500, the use of the foliot in clocks started to decline. The oldest surviving spring-driven clock was made by Jacob Zech in 1525. The first person to suggest using a clock to find longitude while traveling, in 1530, was the Dutch instrument maker Gemma Frisius. The clock would be set to the local time of a known starting point. Then, the longitude of any other place could be found by comparing its local time with the clock's time.

The Ottoman engineer Taqi ad-Din described a weight-driven clock with a verge-and-foliot escapement, gears for striking, an alarm, and a display of the Moon's phases in his book around 1565. Jesuit missionaries brought the first European clocks to China as gifts.

The Italian polymath Galileo Galilei is believed to have realized that a pendulum could be an accurate timekeeper after watching lamps swing in Pisa Cathedral. In 1582, he studied the regular swing of the pendulum and found that its swing only depended on its length. Galileo never built a clock based on his discovery, but before he died, he told his son how to build one.

Modern Accurate Timekeeping

Pendulum Clocks

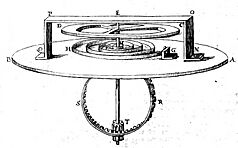

The first truly accurate timekeepers used something called harmonic motion. This is when an object, like a pendulum or a stretched spring, swings back and forth in a very regular way. Harmonic oscillators are great for timekeeping because how long they take to complete one swing doesn't depend on how big the swing is. It only depends on the physical parts of the system.

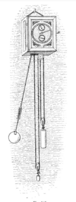

The time when clocks were controlled by harmonic oscillators was the most important period for timekeeping inventions. The first invention of this type was the pendulum clock, designed and built by Christiaan Huygens in 1656. Early versions were off by less than a minute a day, and later ones by only 10 seconds. This was incredibly accurate for the time! Clock faces with minutes and seconds became common after the pendulum clock made such accuracy possible.

The first pendulum clocks used a verge escapement, which needed big swings. But after the anchor mechanism was invented, pendulums could be longer and heavier with smaller, more accurate swings. The first known anchor escapement clock was built by William Clement in 1671.

Jesuits helped a lot with pendulum clocks in the 1600s and 1700s. They really understood how important precision was. For example, the Italian astronomer Father Giovanni Battista Riccioli got nine other Jesuits to count almost 87,000 swings of a pendulum in one day! They helped share and test new scientific ideas and worked with Huygens.

Huygens first used a clock to figure out the equation of time (the difference between actual solar time and clock time). This helped astronomers use stars to measure sidereal time, which was a very accurate way to set clocks. The equation of time was even carved on sundials so clocks could be set using the Sun. In 1720, Joseph Williamson claimed to invent a clock that showed true solar time using special gears.

Other inventions from this time include the rack and snail striking mechanism for clocks that strike the hour, invented by Edward Barlow. Also, the repeating clock (which chimes the hours or minutes on demand) was invented around 1676 by Barlow or Daniel Quare. The deadbeat escapement, which made clocks even more precise, was invented around 1675 by Richard Towneley.

Paris and Blois were early centers for clockmaking in France. French clockmakers like Julien Le Roy were famous for their beautiful clock designs. Le Roy was known as "the most skillful clockmaker in France, possibly in Europe." He invented a special repeating mechanism that made clocks and watches more precise. He also made a clock face that could open to show the inner workings. His discoveries encouraged other researchers to find new ways to measure time even more accurately.

Early pendulum clocks had small errors, but bigger problems came from things like temperature changes. In 1729, the English clockmaker John Harrison invented the gridiron pendulum. It used different metals that expanded and contracted differently with heat. This kept the pendulum's overall length the same, even when the temperature changed. In 1781, George Graham used a glass jar of mercury in his pendulums. Mercury expands faster than glass, helping to keep the pendulum's length steady. Later, in 1895, the invention of invar, a metal alloy that expands very little, largely solved the temperature problem.

After the French Revolution (1794–1795), the French government tried to use decimal time. A day was divided into 10 hours, each with 100 minutes. A clock in Paris kept decimal time until 1801.

Marine Chronometer

After a terrible naval disaster in 1707, where four ships were lost due to navigation errors, the British government offered a huge prize of £20,000 (millions today) to anyone who could figure out how to find longitude accurately at sea. A ship's position could be found if a clock lost or gained less than about six seconds a day. A special group, the Board of Longitude, looked at ideas. One person who tried to win the prize was Jeremy Thacker, who first used the word chronometer in 1714. Huygens built the first sea clock, but it stopped working if the ship moved suddenly.

In 1715, at age 22, John Harrison used his carpentry skills to build an eight-day wooden clock. His clocks had new ideas like using wooden parts to avoid needing oil (and cleaning), rollers to reduce friction, a new kind of escapement, and using two different metals to reduce problems from temperature changes. He went to London to get help from the Board of Longitude to build a sea clock. He was sent to George Graham, who helped him get money for his work. After 30 years, his device, called "H1," was built and tested at sea in 1736. Harrison then designed and made two more sea clocks, "H2" and "H3," ready by 1755.

Harrison also made two watches, "H4" and "H5." Eric Bruton, in his book The History of Clocks and Watches, called H4 "probably the most remarkable timekeeper ever made." After its sea tests in 1761–1762, it was found to be three times more accurate than needed for Harrison to win the Longitude prize!

Electric Clocks

In 1815, the inventor Francis Ronalds made an early electric clock that used static electricity. It was powered by special batteries that lasted a very long time but were affected by air temperature and humidity. He worked on making them more reliable.

In 1840, the Scottish clockmaker Alexander Bain was the first to use electricity to keep a pendulum clock moving. So, he invented the electric clock. In 1841, Bain and John Barwise got a patent for a clock with an electromagnetic pendulum. The English scientist Charles Wheatstone also made his own version of the electric clock, but Bain won a legal fight to be recognized as the inventor.

In 1857, the French physicist Jules Lissajous showed how an electric current could make a tuning fork vibrate forever. This was probably the first time this was used to measure frequency accurately. The special electrical properties of quartz crystals were discovered by French physicist brothers Jacques and Pierre Curie in 1880.

The most accurate pendulum clocks were controlled by electricity. The Shortt–Synchronome clock, designed in 1921, was the first clock that was more accurate than the Earth's own rotation!

Many inventions led to the modern quartz timer. The vacuum tube oscillator was invented in 1912. In 1919, William Eccles used an electrical oscillator to keep a tuning fork moving. This made the vibration much more stable. The first quartz crystal oscillator was built in 1921. In October 1927, the first quartz clock was described by Joseph Horton and Warren Marrison at Bell Telephone Laboratories. For decades, quartz clocks were used in labs for very precise time measurements. They were bulky then, but their amazing stability and accuracy led to them being used everywhere since the 1940s.

The Story of the Watch

The first wristwatches were made in the 1500s. Elizabeth I of England had some in 1572, but they were seen more as jewelry. The first pocketwatches weren't very accurate because they were too small to have perfectly made moving parts. Simpler watches started appearing around 1625.

Clock faces that showed minutes and seconds became common after the invention of the balance spring (or hairspring). This was invented separately in 1675 by Huygens and Hooke. It made the balance wheel swing at a fixed speed. This invention greatly improved the accuracy of mechanical watches, from being off by half an hour a day to just a few minutes. There's still some debate about whether Huygens or Hooke invented it first. Huygens' design for the balance spring is still used in almost all watches today.

Thomas Tompion was one of the first clockmakers to use the balance spring successfully in his pocket watches. This improved accuracy allowed a second hand to be added to the face in the 1690s. Nicolas Fatio de Duillier is credited with designing the first jewel bearings in watches in 1704, which reduced friction and wear.

Other important English clockmakers in the 1700s included John Arnold and Thomas Earnshaw. They focused on making high-quality chronometers and smaller "deck watches" that could fit in a pocket.

Military Use of the Watch

Watches were worn during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871). By the time of the Boer War (1899–1902), watches were seen as a valuable tool. Early models were just regular pocket watches attached to a leather strap. But by the early 1900s, companies started making watches specifically for the wrist. In 1904, Alberto Santos-Dumont, an early aviator, asked his friend, the French watchmaker Louis Cartier, to design a watch he could use during his flights.

During World War I, artillery officers used wristwatches. These "trench watches" were practical because they freed up one hand that would normally be used to hold a pocket watch. They became standard equipment. Soldiers needed to protect the glass of their watches, so sometimes a hinged cage guard was used. This guard made it hard to see the hands, but that problem was solved when shatter-resistant Plexiglass was introduced in the 1930s. Before the war, only women typically wore wristwatches. But during World War I, they became symbols of toughness for men.

Modern Watches

Pocket watches started to be replaced around the early 1900s. Switzerland, which was neutral during World War I, made wristwatches for both sides of the conflict. The invention of the tank influenced the design of the Cartier Tank watch. Watch designs in the 1920s were also influenced by the Art Deco style. The automatic watch, which winds itself, was reintroduced in the 1920s by English watchmaker John Harwood. After his company went bankrupt, other companies like Rolex started making them. In 1930, Tissot made the first non-magnetic wristwatch.

The first battery-powered watches were developed in the 1950s. High-quality watches were made by companies like Patek Philippe. For example, a Patek Philippe watch from 1941, possibly the most complex wristwatch ever made in stainless steel, sold for over $11 million in 2016!

The manual winding Speedmaster Professional, or "Moonwatch," was worn during the first U.S. spacewalk (Gemini 4 mission) and was the first watch worn by an astronaut walking on the Moon during the Apollo 11 mission. In 1969, Seiko made the world's first quartz wristwatch, the Astron.

In the 1970s, digital watches made with transistors and plastic parts became popular. This allowed companies to make watches with fewer workers. Many traditional watch companies that used more complicated metalworking methods went out of business.

Smartwatches, which are basically small computers worn on the wrist, came out in the early 2000s.

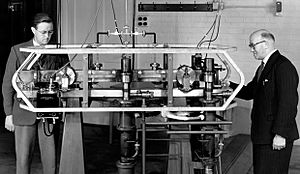

Atomic Clocks

Atomic clocks are the most accurate timekeeping devices we use today. They are accurate to within a few seconds over many thousands of years! They are used to set and check other clocks and timekeeping tools. The U.S. National Bureau of Standards (now NIST) started using atomic clocks as their main time standard in the 1960s.

The idea of using atoms to measure time was first suggested by Lord Kelvin in 1879. But it wasn't until the 1930s, with the development of magnetic resonance, that it became possible. A test device using ammonia was built in 1948. Even though it wasn't as accurate as existing quartz clocks, it proved that the idea of an atomic clock worked.

The first truly accurate atomic clock was built by the English physicist Louis Essen in 1955. It was based on a specific change in the caesium-133 atom. It was set using astronomical time.

In 1967, the International System of Units (SI) decided that the unit of time, the second, would be based on the properties of caesium. The SI defined the second as 9,192,631,770 cycles of the radiation that happens when the caesium-133 atom changes its energy level. The caesium atomic clock kept by NIST is accurate to 30 billionths of a second per year. Atomic clocks have also used other elements like hydrogen and rubidium vapor. Hydrogen clocks are even more stable, and rubidium clocks are smaller, use less power, and cost less.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la relojería para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la relojería para niños

- Dimensional metrology

- Forensic metrology

- Smart Metrology

- Time metrology

- Quantum metrology

- Clock synchronization

- Clockmaker

- Coordinated Universal Time (UTC)

- History of timekeeping devices in Egypt

- Quartz crisis

- Seconds pendulum

- Time metrology

- Time standard

- Timeline of time measurement inventions

- Watchmaker

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |