Métis facts for kids

| Métis | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Total population | |

| 587,545 (2016, census) | |

| Canada | 587,545 |

| United States | Unknown |

| Languages | |

| Michif, Cree, Chiac, Canadian French, American English, Canadian English, Hand Talk, Bungee, other indigenous languages | |

The Métis are Indigenous people in Canada and parts of the United States. They are special because they have both Indigenous and European (mostly French) family backgrounds. In Canada, they are seen as a unique culture. They are one of three groups of Canadian Indigenous peoples mentioned in the Constitution.

Not all Métis belong to the "Métis Nations" that have organized groups. These groups are found between the Great Lakes region and the Rocky Mountains. However, the word "Métis" has historically meant all people with mixed Indigenous North American and European heritage. Some groups, like the Manitoba Metis Federation, disagree with this broad meaning. Since the late 20th century, Métis in Canada have been recognized as a distinct Indigenous people. This recognition came under the Constitution Act of 1982. In 2016, there were 587,545 Métis people in Canada.

Smaller groups who call themselves Métis live in Canada and the United States. An example is the Little Shell Tribe in Montana. The Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians are recognized as Indian. There is a discussion even within the Little Shell Tribe about whether Métis should be allowed to join. The Métis culture began during the fur trade. They have been very important in Canada's history. They also helped create the province of Manitoba. Métis Nation communities exist in both the U.S. and Canada. These communities were separated by the 49th parallel North border. Alberta is the only Canadian province with recognized Métis Nation land. These are the eight Métis Nation Settlements. About 5,000 people live on 1.25 million acres (5060 km2) of land there.

Contents

- What Does "Métis" Mean?

- Louis Riel's Thoughts on Métis Identity

- Métis People in Canada

- Where Métis People Live in Canada

- Who Identifies as Métis?

- How Identity Was Seen in the Past

- No Clear Legal Definition

- Métis Organizations and Their Definitions

- What Defines Métis Culture?

- History of the Métis People

- Land Ownership for Métis

- Métis Settlements in Alberta

- Métis Organizations Today

- Métis Culture and Language

- How Many Métis People Are There?

- Métis People in the United States

- The Medicine Line (Canada–U.S. Border)

- See also

What Does "Métis" Mean?

The word Métis comes from French and means "mixed-blood". It is similar to the Spanish word mestizo. Michif is a special language spoken by some Métis people. It is a mix of Plains Cree and Canadian French.

The French word métis was used in the 16th century. It described people of mixed European and Indigenous American parents in New France. This area stretched from Quebec to the Mississippi River. At first, it meant French-speaking people with some French family background. Later, it was used for mixed European and Indigenous people in other French colonies. These included places like Guadeloupe and Senegal. When spelled with a capital M, Métis refers to the distinct Indigenous people in Canada and the U.S. With a small m, métis is an adjective. There are many ways to spell Métis. The most common spelling today is Métis. However, some prefer "Metis" to include people of both English and French descent. The meaning of the word is often debated. Governments and groups have defined it, rather than the Métis themselves.

The Métis of Canada and the Métis of the United States adopted parts of both cultures. They created their own customs, traditions, and a shared language. Some believe the Métis became a distinct group when they organized politically. This happened at the Battle of Seven Oaks in 1816. Others think it started earlier, before they moved to the Western plains.

Louis Riel's Thoughts on Métis Identity

Louis Riel was an important Métis political leader. He wrote a lot about his people. In one of his writings, The Métis, Louis Riel's Last Memoir, he explained:

The Métis have European fathers, who worked for fur trade companies. Their mothers were Indigenous women from different tribes.

The French word Métis comes from the Latin word mixtus, meaning "mixed". It describes us well.

The English word "Half-Breed" was okay for the first generation. But now, European and Indigenous blood are mixed in many ways. So, it doesn't fit anymore.

The French word Métis shows this mixture perfectly. Because of this, it is a good name for our people.

Here's a small thought, without meaning to offend anyone.

Very kind people might sometimes tell a Métis, “You don't look Métis at all. You can't have much Indigenous blood. You could easily pass for pure White.”

The Métis might feel a bit confused by these comments. They want to honor both parts of their family. But they worry about upsetting these kind people. While they think of what to say, comments like "You have hardly any Indigenous blood. It's not even worth mentioning" silence them. Here's what the Métis think privately.

"It is true that our Indigenous background is humble. But it is right that we honor our mothers as well as our fathers. Why should we care how much European or Indigenous blood we have? No matter how little we have of either, shouldn't we say, 'We are Métis,' out of thanks and love for our families?"

Métis People in Canada

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 587,545 (2016) 1.7% of the Canadian population (including persons of partial Métis parentage) |

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Ojibwe, Cree and Christianity (Protestantism and Catholic) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

Métis people in Canada are specific cultural groups. Their family history goes back to First Nations and European settlers. These settlers were mainly French, from the early days of Canada's colonization. Métis people are recognized as one of Canada's Aboriginal peoples. This recognition is under the Constitution Act of 1982. They are recognized along with First Nations and Inuit peoples. In 2014, the Supreme Court of Canada decided that Métis are "Indians" under a part of the Constitution. Canadian Métis make up most people who identify as Métis. There are also Métis in the United States. In Canada, 587,545 Métis were counted in 2016. About 20.5% live in Ontario and 19.5% in Alberta.

The Métis first developed from mixed-race families. These were usually Indigenous women and French settler men. Over many generations, especially in central and western Canada, a unique Métis culture grew. In eastern Canada, Indigenous women were often from the Wabanaki and Algonquin groups. In Western Canada, they were Saulteaux, Cree, Ojibwe, Nakoda, and Dakota/Lakota. Their marriages with European fur traders were often called marriage à la façon du pays (marriage "according to the custom of the country").

After New France became part of Great Britain in 1763, there was a difference. There were French Métis (from French fathers) and Anglo-Métis (from English or Scottish fathers). Today, these two cultures have largely blended into local Métis traditions. This does not mean there aren't other Métis cultures across North America. Historically, these mixed-heritage people were called by other names. Many of these names are now considered offensive.

While Métis culture is found across Canada, their traditional "homeland" is in the Canadian Prairies. The most famous group are the "Red River Métis". They are centered in southern and central Manitoba along the Red River of the North.

The Métis in the United States are closely related. They live mainly in border areas like Northern Michigan and Eastern Montana. These areas had a lot of mixing between Indigenous and European people. This was due to the North American fur trade in the 19th century. However, Métis in the U.S. do not have federal recognition.

Where Métis People Live in Canada

Here is a table showing where Métis people live in Canada, based on 2016 data from Statistics Canada.

| Province / Territory | Percentage of Métis (out of total population) |

|---|---|

| Canada — Total | 1.7% |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1.5% |

| Prince Edward Island | 0.6% |

| Nova Scotia | 2.8% |

| New Brunswick | 1.5% |

| Quebec | 0.8% |

| Ontario | 1.0% |

| Manitoba | 7.3% |

| Saskatchewan | 5.2% |

| Alberta | 2.9% |

| British Columbia | 2.0% |

| Yukon | 2.9% |

| Northwest Territories | 7.1% |

| Nunavut | 0.5% |

Who Identifies as Métis?

In 2016, 587,545 people in Canada said they were Métis. They made up 35.1% of all Aboriginal people. They were 1.5% of the total Canadian population. Most Métis today are descendants of many generations of Métis individuals. They live in cities. Some Métis live in rural and northern areas, close to First Nations communities.

Over the last century, many Métis have blended into the general European Canadian population. Having Métis heritage is more common than people realize. Scientists believe that 50% of people in Western Canada today have some Aboriginal family background. Most people with distant Aboriginal family ties do not consider themselves part of the Métis culture.

Unlike First Nations people, there is no difference between Treaty status and non-Treaty status for Métis. The Métis did not sign treaties with Canada. One exception was an agreement to Treaty 3 in Northwest Ontario. However, the government never put this agreement into action. The legal definition of Métis is still developing. Section Thirty-five of the Constitution Act, 1982 recognizes the rights of Indian, Métis, and Inuit people. But it does not define these groups. In 2003, the Supreme Court of Canada defined a Métis person. They said it is someone who identifies as Métis. They must also have a family link to a historic Métis community. And they must be accepted by a modern Métis community that connects to that history.

How Identity Was Seen in the Past

The most well-known mixed-heritage group in Canadian history are those who grew during the fur trade. They lived in south-eastern Rupert's Land, especially in the Red River Settlement (now Manitoba). In the late 1800s, they organized politically. They had conflicts with the Canadian government to protect their independence.

Mixing between European and Indigenous people happened in many places. It was part of colonization from the very beginning in the Americas. But the strong sense of identity among the Métis along the Red River was special. They mostly spoke French and Michif. Their armed resistance, led by Louis Riel, made the term "Métis" widely known in Canada.

Because of their organizing, the Métis gained official recognition. The national government recognized them as one of the Aboriginal groups. This was in S.35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. This section says:

35. (1) The existing Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal People of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.

- (2) In this Act, "Aboriginal Peoples of Canada" includes the Indian, Inuit, and Métis Peoples of Canada.

- ...

— Constitution Act, 1982

Section 35(2) does not say who counts as Métis. This has led to questions. Should "Métis" only mean descendants of the Red River Métis? Or should it include all mixed-heritage groups? Many First Nations people have mixed ancestry. But they identify mainly with their tribal nation, not as Métis. Since the 1982 Act, many groups not related to the Red River Métis have started using the word "Métis".

No Clear Legal Definition

It is not clear who has the right to define the word "Métis". There is no full legal definition of Métis status in Canada. This is different from the Indian Act. That act creates a list for all (Status) First Nations people. Some say that Indigenous people should define their own identity. This would mean no government definition is needed. The question is who should get Aboriginal rights based on Métis identity. No federal law defines the Métis.

Alberta is the only province that has defined the term in its law. The Métis Settlements Act (MSA) says a Métis is "a person of Aboriginal ancestry who identifies with Métis history and culture". This definition helps decide who can be a member of Alberta's eight Métis settlements. The MSA, along with community rules, sets the legal requirements for living on these settlements. In Alberta law, being part of a "Métis Association" does not give the same rights as being a member of the Alberta Métis Settlements. The MSA does not include Status Indians. This was supported by the Supreme Court in 2011.

The number of people identifying as Métis has grown a lot since the late 20th century. Between 1996 and 2006, it almost doubled to about 390,000. Before the R v. Powley case in 2003, there was no legal definition of Métis. The only exception was the rules in the Métis Settlements Act of 1990.

The Powley case involved Steven Powley and his son Rodney. They were Métis from Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. They claimed Métis hunting rights. The Supreme Court of Canada listed three main things to identify Métis with hunting rights:

- identifying as a Métis person;

- having a family link to a historic Métis community; and

- being accepted by a Métis community.

All three must be true for someone to be Métis under this legal definition. The court also said that "Métis" in the Constitution does not include all people with mixed Indigenous and European heritage. Instead, it means distinct peoples who developed their own customs and identity. The court was clear that its test was not a complete definition of Métis.

Questions remain about whether Métis have treaty rights. This is a big issue in the Canadian Aboriginal community. Some say that only First Nations could sign treaties with the government. So, by this idea, Métis would have no Treaty rights. However, one treaty, the Halfbreed (Métis in French) Adhesion to Treaty 3, names Métis. Another, the Robinson Superior Treaty of 1850, listed 84 "half-breeds" and included them. Many Métis were included in other treaties at first. But they were later excluded by changes to the Indian Act.

Métis Organizations and Their Definitions

Two main groups speak for the Métis in Canada: the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples (CAP) and the Métis National Council (MNC). They have different ways of defining Métis people. The CAP represents all Aboriginal people not part of the reserve system. This includes Métis and non-Status Indians. It uses a broad idea based on self-identification.

The Métis National Council separated from CAP's earlier group in 1983. Its leaders felt that a "pan-Aboriginal approach" did not let the Métis Nation represent itself well. The MNC sees the Métis as one nation. They believe this nation has a shared history and culture. This culture is centered on the fur trade in "west-central North America" in the 1700s and 1800s. This view is often debated.

In 2003, MNC had five provincial groups:

- Métis Nation of Ontario Secretariat,

- Manitoba Métis Federation Incorporated,

- Métis Nation of Saskatchewan,

- Métis Nation of Alberta Association, and the

- Métis Nation of British Columbia.

The Métis Nation of Alberta Association adopted this definition:

Métis means a person who identifies as a Métis, is different from other Aboriginal peoples, has historic Métis Nation family ties, and is accepted by the Métis Nation.

Many local, independent Métis groups have started in Canada. In Northern Canada, neither CAP nor MNC have groups. Here, local Métis groups work directly with the federal government. They are part of the Aboriginal land claims process. Three modern treaties in the Northwest Territories include benefits for Métis people. These are for those who can prove local Aboriginal family ties before 1921.

The federal government recognizes the Métis National Council. In December 2016, Prime Minister Trudeau promised to meet yearly with leaders from First Nations, Inuit, and the Métis National Council. He also promised to work on other things to respond to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's Calls to Action.

Indigenous Affairs Canada, the government department, works with the MNC. In April 2017, they signed the Canada-Métis Nation Accord. This agreement aims to work with the Métis Nation, through the Métis National Council, on a Nation-to-Nation basis.

After the Powley ruling, Métis groups started giving Métis Nation citizenship cards. Several groups are registered with the Canadian government to give these cards. The rules for getting a card and the rights it gives are different for each group. For example, to join the Métis Nation of Alberta Association (MNAA), you need to show your family tree. It must go back to the mid-1800s and prove you are related to historic Métis groups.

The Métis Nation of Ontario requires applicants to "see themselves and identify themselves as distinctly Métis." This means they must choose to be culturally Métis. They also note that "an individual is not Métis simply because he or she has some Aboriginal ancestry, but does not have Indian or Inuit status." It also needs proof of Métis ancestry. This means a family link to a "Métis ancestor," not just an Indian or Aboriginal ancestor.

What Defines Métis Culture?

Cultural ideas of Métis identity help shape legal and political ones.

The 1996 Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples said:

Many Canadians have mixed Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal family ties. But that does not make them Métis or even Aboriginal... What makes Métis people different is that they connect with a culture that is clearly Métis.

Traditional signs of Métis culture include using mixed languages. These are languages like Michif (French-Cree-Dene) and Bungi (Cree-Ojibwa-English). They also include special clothing, like the arrow sash (ceinture flêchée). A rich tradition of fiddle music, jigs, and square dances is also part of their culture. Their traditional way of life was based on hunting, trapping, and gathering. However, it is now more understood that not all Métis hunted, wore the sash, or spoke Michif.

History of the Métis People

How the Métis Began

During the peak of the North American fur trade in New France from 1650, many French and British fur traders married First Nations and Inuit women. These women were mainly Cree, Ojibwa, or Saulteaux. These marriages were often called marriage à la façon du pays or marriage "according to the custom of the country."

At first, the Hudson's Bay Company did not allow these relationships. But many Indigenous people encouraged them. These marriages created family ties that helped the trade between Indigenous people and Europeans. When Indigenous women married European men, they taught them about their people, culture, and the land. They also worked with them. Indigenous women paddled canoes, made moccasins, netted snowshoe webbing, and dried meat for pemmican. They also helped make birchbark canoes. Marriages between cultures made the fur trade more successful.

The children of these marriages often learned Catholicism. But they mostly grew up in First Nations societies. They were seen as a link between Europeans and First Nations and Inuit peoples. As adults, the men often worked as interpreters for fur-trade companies. They also became fur trappers. Many early Métis lived within their wives' First Nations societies. They also started marrying other Métis women.

By the early 1800s, marriages between European fur traders and First Nations or Inuit women started to decrease. European fur traders began to marry Métis women instead. This was because Métis women understood both European and Indigenous cultures. They could also interpret.

The Métis were very important to the success of the western fur trade. They were skilled hunters and trappers. They were raised to value both Aboriginal and European cultures. Métis understanding of both societies helped bridge cultural differences. This led to better trading relationships. The Hudson's Bay Company did not like marriages between their traders and Indigenous women. But the North West Company (an English-speaking fur trading company) supported such marriages. Trappers often married First Nations women and worked outside company rules. The Métis people were respected by both fur trade companies. This was because of their skills as voyageurs, buffalo hunters, and interpreters. They also knew the lands well.

By the early 1800s, European immigrants, mostly Scottish farmers, moved to the Red River Valley. Métis families from the Great Lakes region also moved there. This area is now in Manitoba. The Hudson's Bay Company controlled this land, called Rupert's Land. They gave land plots to European settlers. This caused problems with those already living there. It also caused conflict with the North West Company, whose trade routes were cut. Many Métis worked as fur traders for both companies. Others were free traders or buffalo hunters. They supplied pemmican to the fur trade. Buffalo numbers were dropping, so Métis and First Nations had to travel farther west to hunt. Fur trade profits were also falling.

Most mentions of the Métis in the 1800s were about the Plains Métis, especially the Red River Métis. But the Plains Métis often identified by their jobs. These included buffalo hunters, pemmican and fur traders, and "tripmen" in the York boat fur brigades. Women were moccasin sewers and cooks. The largest community in the Assiniboine-Red River area had a different lifestyle. This was different from Métis in the Saskatchewan, Alberta, Athabasca, and Peace river valleys.

In 1869, Canada gained control of Rupert's Land from the Hudson's Bay Company. The Government of Canada began to assert its power. The Métis and the Anglo-Métis (called Countryborn) joined together. They wanted to protect their traditional ways of life. They were against the Anglo-Canadian government. A census in 1870 in Manitoba showed 11,963 people. Of these, 5,757 were Métis and 4,083 were English-speaking Mixed Bloods.

During this time, the Canadian government signed treaties with various First Nations. These Nations gave up land rights in the western plains to Canada. In return, the government promised food, education, and medical help. While the Métis generally did not sign treaties as a group, they were sometimes included. They were even listed as "half-breeds" in some records.

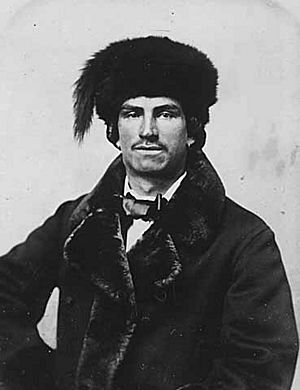

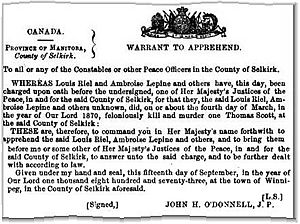

In the late 1800s, after the British North America Act (1867), Louis Riel became a Métis leader. He was educated. In August 1869, he spoke out against Canadian government surveys on Métis lands. The Métis became more worried when William McDougall, who was against French speakers, was made Lieutenant Governor. This happened on September 28, 1869, before the land transfer in December. On November 2, 1869, Louis Riel and 120 men took over Upper Fort Garry. This was the first act of Métis resistance. On March 4, 1870, the Provisional Government, led by Riel, executed Thomas Scott. Scott was found guilty of not obeying orders and treason. The elected Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia then sent three people to Ottawa. They negotiated with the Canadian government. This led to the Manitoba Act and Manitoba joining Canada. Because Scott was executed, Riel was charged with murder and fled to the United States.

In March 1885, the Métis heard that 500 North-West Mounted Police were coming west. They organized and formed the Provisional Government of Saskatchewan. Pierre Parenteau was President, and Gabriel Dumont was adjutant-general. Riel led a few hundred armed men. They were defeated by Canadian forces in the North-West Rebellion, from March 26 to May 12, 1885. Gabriel Dumont fled to the United States. Riel, Poundmaker, and Big Bear surrendered. Big Bear and Poundmaker were each sentenced to three years. On July 6, 1885, Riel was found guilty of high treason. He was sentenced to hang. Riel appealed, but he was executed on November 16, 1885.

Land Ownership for Métis

Land ownership became a big issue. The Métis sold most of the 600,000 acres (2430 km2) they received in the first settlement.

In the 1930s, Métis communities in Alberta and Saskatchewan became more active. They fought for land rights. Some filed claims to get certain lands back. Five men, called "The Famous Five," helped the Alberta government. They were James P. Brady, Malcolm Norris, Peter Tomkins Jr., Joe Dion, and Felix Callihoo. They helped form the 1934 "Ewing Commission" to deal with land claims. The Alberta government passed the Métis Population Betterment Act in 1938. This Act gave funding and land to the Métis. (The provincial government later took back some of this land.)

Métis Settlements in Alberta

- "Our People, Our Land, Our Culture, Our Future" – Métis settlements motto

The Métis settlements in Alberta are the only recognized Métis land base in Canada. They are governed by a unique Métis government called the Métis Settlements General Council (MSGC). The MSGC represents the Federated Métis Settlements at all levels. It owns 1.25 million acres (5060 km2) of land. This makes the MSGC the largest land owner in the province, besides the Crown. The MSGC is the only recognized Métis Government in Canada with specific land, power, and authority. This comes from the Métis Settlements Act.

The Métis settlements are mostly made up of Indigenous Métis people native to Northern Alberta. They are different from those in Red River, the Great Lakes, and other Métis from further east. However, after the Riel and Dumont resistances, some Red River Métis moved west. They married into the Métis settlement populations in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Historically, the Métis of Northern Alberta were called "Nomadic Half-breeds." Their fight for land is still seen today in the eight Métis settlements.

The Métis settlements, first called Half-Breed Colonies, were formally created in the 1930s. This was done by a Métis political group. The Métis people in Northern Alberta were the only Métis to get communal Métis lands. During renewed Indigenous activism in the 1960s and 1970s, Métis political groups were formed or restarted. In Alberta, the Métis settlements united as: The "Alberta Federation of Métis Settlement Associations" in the mid-1970s. Today, the Federation is represented by the Métis Settlements General Council.

During the constitutional talks of 1982, the Métis were recognized as one of Canada's three Aboriginal peoples. This was partly due to the Federation of Métis Settlements. In 1990, the Alberta government restored land titles to the northern Métis communities. This was done through the Métis Settlement Act. This new law replaced the Métis Betterment Act. The first Métis settlements in Alberta were called colonies and included:

- Buffalo Lake (Caslan) or Beaver River

- Cold Lake

- East Prairie (south of Lesser Slave Lake)

- Elizabeth (east of Elk Point)

- Fishing Lake (Packechawanis)

- Gift Lake (Ma-cha-cho-wi-se) or Utikuma Lake

- Goodfish Lake

- Kikino

- Kings Land

- Marlboro

- Paddle Prairie (or Keg River)

- Peavine (Big Prairie, north of High Prairie)

- Touchwood

- Wolf Lake (north of Bonnyville)

In the 1960s, the settlements of Marlboro, Touchwood, Cold Lake, and Wolf Lake were closed by the Alberta Government. The remaining Métis Settlers had to move to one of the eight remaining Métis Settlements.

The position of Federal Interlocutor for Métis and Non-Status Indians was created in 1985. This was a role in the Canadian Cabinet. The Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development is mainly responsible for Status Indians living on Indian reserves. The new position was created to connect the federal government with Métis and non-status Aboriginal peoples, and urban Aboriginals.

Métis Organizations Today

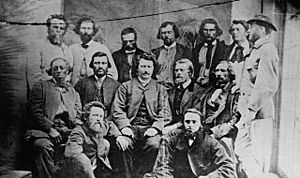

The Provisional Government of Saskatchewan was a state declared by Louis Riel during the North-West Rebellion of 1885. Its council was called the Exovedate. It discussed military plans and local rules. It met at Batoche, Saskatchewan. This government lost power after the Battle of Batoche.

The Métis National Council was formed in 1983. This was after the Métis were recognized as an Aboriginal People in Canada. This recognition came in Section Thirty-five of the Constitution Act, 1982. The MNC was part of the World Council of Indigenous (WCIP). In 1997, the Métis National Council gained special status with the United Nations. Clement Chartier was their first ambassador to this group. MNC is also a founding member of the American Council of Indigenous Peoples (ACIP).

The Métis National Council includes five provincial Métis organizations:

- Métis Nation British Columbia

- Métis Nation of Alberta

- Métis Nation-Saskatchewan

- Manitoba Métis Federation

- Métis Nation of Ontario

The Métis people hold elections for political positions in these groups. These elections happen regularly for regional and provincial leaders. Métis citizens and their communities are part of these Métis governments. They do this through elected Local or Community Councils and yearly provincial assemblies.

The Congress of Aboriginal Peoples (CAP) and its nine regional groups represent all Aboriginal people not on reserves. This includes Métis and non-Status Indians.

Because of political differences with the MNBC, a separate Métis group was formed in British Columbia in June 2011. It is called the British Columbia Métis Federation (BCMF). They are not connected to the Métis National Council. The government has not officially recognized them.

The Canadian Métis Council–Intertribal is in New Brunswick. It is not connected to the Métis National Council.

The Ontario Métis Aboriginal Association–Woodland Métis is in Ontario. It is not connected to the Métis National Council. Its members believe the MNC focuses too much on the Métis of the prairies. The Woodland Métis are also not connected to the Métis Nation of Ontario (MNO). MNO President Tony Belcourt said in 2005 that he did not know who OMAA members were, but that they were not Métis. In a Supreme Court of Canada appeal, the federal government stated that being a member of OMAA or MNO does not prove membership in a specific local Aboriginal community.

The Nation Métis Québec is not connected to the Métis National Council.

None of these groups claim to represent all Métis. Other Métis groups also focus on recognizing and protecting their culture. They show their communities' strong family ties and culture. This culture came from settling in historic villages along the fur trade routes.

Métis Culture and Language

Language

Most Métis once spoke, and many still speak, either Métis French or an Indigenous language. These include Mi'kmaq, Cree, Anishinaabemowin, and Denésoliné. A few in some areas spoke a mixed language called Michif. Michif uses Plains Cree verbs and French nouns. Michif is how Métis people say Métif, a different way to say Métis. Today, most Métis speak Canadian English. Canadian French is a strong second language. They also speak many Aboriginal languages. Métis French is best kept alive in Canada.

Michif is used most in the United States. This is especially true in the Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation in North Dakota. There, Michif is the official language of the Métis who live on this Chippewa (Ojibwe) reservation. After years of these languages being used less, the provincial Métis councils are encouraging their return. They are teaching them in schools and using them in communities. The use of Métis French and Michif is growing again.

The Anglo-Métis, also known as Countryborn, were a group in the 1800s. They were children of people in the Rupert's Land fur trade. They usually had Scottish or English fathers and Aboriginal mothers. Their first languages would have been Aboriginal languages like Cree language, Saulteaux language, or Assiniboine language, and English. The Gaelic and Scots spoken by Scots became part of a creole language called "Bungee".

Flag

The Métis flag is one of the oldest patriotic flags from Canada. The Métis have two flags. Both flags have the same design: a central infinity symbol. But they are different colors. The red flag was the first one used. It is the oldest flag made in Canada that is still used today. The first red flag was given to Cuthbert Grant in 1815 by the North-West Company. Days before the Battle of Seven Oaks in 1816, Peter Fidler saw Cuthbert Grant flying the blue flag. The red and blue colors do not represent culture or language. They also do not represent the companies.

Lowercase 'm' versus Uppercase 'M'

The word "Métis" is originally French. It was used for mixed-race children of French colonists and women from colonized areas. This happened in all of France's colonies worldwide. The first records of "Métis" were made around 1600 on Canada's East Coast (Acadia). This is where French exploration began.

As French Canadians followed the fur trade west, they formed more families with different First Nations women, including the Cree. Descendants of English or Scottish men and Indigenous women were called "half-breeds" or "country born." They sometimes adopted a farming culture and were often raised Protestant. The term "Métis" eventually grew to include all "half-breeds" or people of mixed First Nations-European ancestry. This included those not from the historic Red River Métis.

Lowercase 'm' métis refers to people with mixed Indigenous and other ancestry. It recognizes many people with varied racial backgrounds. Capital 'M' Métis refers to a specific cultural heritage and identity. This identity is based on more than just race. Some argue that people who identify as métis should not be included in the definition of 'Métis'. Others think this difference is new and unfair. They say it creates new boundaries to exclude "other Métis."

Most Métis have suggested that only descendants of the Red River Métis should be recognized in the Constitution. This is because they developed the most distinct culture as a people in historic times. Some claim this would exclude Métis from the Maritimes, Quebec, and Ontario. It would classify them only as lowercase m métis. In a recent decision, the Supreme Court of Canada said:

[17] There is no agreement on who is Métis or a non-status Indian. Nor does there need to be. Cultural and ethnic labels do not have clear boundaries. ‘Métis’ can mean the historic Métis community in Manitoba’s Red River Settlement. Or it can be a general term for anyone with mixed European and Aboriginal heritage. Some mixed-ancestry communities identify as Métis, others as Indian:

- There is no one exclusive Métis People in Canada, just as there is no one exclusive Indian people in Canada. The Métis of eastern Canada and northern Canada are as different from Red River Métis as any two peoples can be... As early as 1650, a distinct Métis community developed in LeHeve [sic], Nova Scotia. It was separate from Acadians and Micmac Indians. All Métis are Aboriginal people. All have Indian ancestry.

How Many Métis People Are There?

According to the 2016 Canada Census, 587,545 people said they were Métis. However, it is not certain that all these people would meet the legal tests. These tests were set out in the Supreme Court decisions Powley and Daniels. Therefore, not all would qualify as "Métis" for Canadian law.

Métis People in the United States

|

|

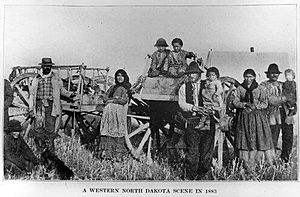

Paul Kane's oil painting Half-Breeds Running Buffalo, depicting a Métis buffalo hunt on the prairies of Dakota in June 1846. |

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Languages | |

|

|

| Religion | |

| Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

The Métis people in the United States are a specific culture and community. They are descendants of Native American and early European colonist parents. Usually, these were Indigenous women who married French (and later Scottish or English) men. These men were called Freemen. They worked as fur trappers and traders in the 1700s and 1800s. The Métis developed as an ethnic and cultural group from these families. The women were usually Algonquian, Ojibwe, and Cree.

In the French colonies, people of mixed Indigenous and French family were called métis in French, meaning "mixture." These people were bilingual. They could trade European goods, like muskets, for furs and hides at a trading post. These Métis were found throughout the Great Lakes area and west to the Rocky Mountains. While the word first just meant "mixed," it grew to become an ethnicity in the 1800s. This use (meaning simply "mixed") does not include mixed-race people from other situations or more recently than about 1870.

There are fewer Métis in the U.S. than in Canada. In the early colonial days, there was no border between Canada and the British colonies. People moved freely. While both communities have the same origins, the Canadian Métis have developed more as an ethnic group than those in the U.S.

As of 2018, Métis people lived in Michigan, Illinois, Ohio, Minnesota, North Dakota, and Montana.

Where Métis Lived in the U.S.

As French and British fur traders explored North America, European men often had relationships and marriages with Native American women. Both sides often felt these marriages helped the fur trade. Indigenous women often acted as interpreters. They could introduce the European men to their people. Many Native American and First Nations groups had matrilineal family systems. This meant mixed-race children were considered part of their mother's clan. They were usually raised in her culture. Fewer were educated in European schools. Métis men in the northern areas typically worked in the fur trade. Later, they became hunters and guides. Over time, in certain areas, especially the Red River of the North, the Métis became a distinct ethnic group with their own culture.

History of Métis in the U.S.

Between 1795 and 1815, Métis settlements and trading posts were set up. These were in what are now the US states of Michigan and Wisconsin, and less so in Illinois and Indiana. As late as 1829, the Métis were very important in the economy of present-day Wisconsin and Northern Michigan.

In the early days of Michigan Territory, Métis and French people played a big role in elections. With Métis support, Gabriel Richard was elected to Congress. After Michigan became a state, more European-American settlers came from eastern states. Many Métis moved west to the Canadian Prairies. This included the Red River Colony. Others identified with Chippewa groups. Many others blended into an ethnic "French" identity, like the Muskrat French. By the late 1830s, only in Sault Ste. Marie were the Métis widely recognized as an important part of the community.

Another major Métis settlement was La Baye, where Green Bay, Wisconsin is today. In 1816, most of its residents were Métis.

In Montana, a large group of Métis from the Pembina region hunted there in the 1860s. By 1880, they formed a farming settlement in the Judith Basin. This settlement eventually broke apart. Most Métis left or identified more strongly as "white" or "Indian."

Métis people often had marriages between different races. The French saw these marriages as practical. Americans, however, saw mixed-race marriages as wrong. They believed in racial purity. Even though it was legal, these marriages often led to a loss of social standing for the spouse of higher class. It also affected any children. The French, however, seemed to encourage fur traders to marry Indigenous women. They believed it helped the fur trade and spread religion. Generally, these marriages were happy and lasted. They brought different groups of people together and helped the fur trade.

Current Métis Population in the U.S.

Mixed-race people live throughout Canada and the northern United States. But only some in the US identify culturally as Métis. A strong Prairie Métis identity exists in the "homeland" once known as Rupert's Land. This area extends south from Canada into North Dakota, especially west of the Red River of the North. The historic Prairie Métis homeland also includes parts of Minnesota and Wisconsin. Many people who identify as Métis live in North Dakota, mostly in Pembina County. Many members of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians (a federally recognized Tribe) identify as Métis or Michif.

Many Métis families are recorded in the U.S. Census for historic Métis settlement areas. These include along the Detroit and St. Clair rivers, Mackinac Island, and Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. Also, Green Bay in Wisconsin. Their families often formed during the early 1800s fur trading era.

The Métis have generally not organized as an ethnic or political group in the United States. This is different from Canada, where they had armed conflicts to secure a homeland.

The first "Conference on the Métis in North America" was held in Chicago in 1981. This happened after more research about these people. It was also a time when different ethnic groups were better appreciated. The history of North America's settlement was also being re-examined. Papers at the conference focused on "becoming Métis." They also looked at how history shaped this ethnic group, which has Aboriginal status in Canada. The people and their history continue to be studied a lot, especially by scholars in Canada and the United States.

These groups are different from other 'tri-racial isolate' groups. Examples are the Munguelons, Ramapo Mountain People, the We-Sort, the Brass Ankles, and the Red Bones.

Louis Riel and the United States

Riel had a big impact on the Métis community in Canada, especially in Manitoba. But he also had a special connection with the Métis in the United States. At the time of his execution, he was an American citizen. Riel tried to be a leader for the Métis community in the United States. He greatly helped defend Métis rights, especially for those in the Red River region.

On October 22, 1844, Louis Riel was born in the Red River settlement, in the territory of Assiniboia. He had a British background. But because the Métis were a mobile community, he traveled a lot. He had a changing identity, often crossing the Canada and United States border. In the 1800s, few American citizens lived in Red River.

Riel greatly helped defend Métis justice. On November 22, 1869, Riel arrived in Winnipeg. He discussed the rights of the Métis community with McDougall. At the end of the talks, McDougall agreed to guarantee a “List of Rights.” That statement also included four parts of the Dakota bill of rights. This Bill of Rights showed the growing American Métis influence during the Red River Métis revolution. It was an important step in Métis justice.

The following years saw constant conflict between the government and the Métis people. This also caused problems with the citizenship of Métis leaders, like Louis Riel. He was crossing the border without proper notice. This led to problems for Riel. The Ontario government wanted him. He was later accused in the Scott Death case, which was decided without a proper trial. By 1874, there was a warrant for his arrest in Winnipeg. Because of the warrant in Canada, Riel saw the United States as a safer place for himself and the Métis people. Riel spent most of his time in the United States, running from the Canadian government. Riel struggled with mental health issues. From 1875-1878, he decided to get treatment in the American northeast. Once better, he decided to change his life by becoming an American resident. He wanted to finish the work of freeing the Métis people that he started in 1869. With help from the United States military, Riel wanted to invade Manitoba to gain control. However, the American military refused his idea. They did not want to cause conflict with the Canadian military. He then tried to create an alliance between Aboriginal and Métis people. This also did not work. In the end, his main goal was to improve the living conditions and rights of the Métis people in the United States. Riel's failed attempts to defend the Métis community led to more mental health problems and hospitalization in Quebec.

Riel returned to Montana from 1879 to continue his mission. He wanted to defend the Métis community in the United States. Riel wanted the Métis and Native people of the region to join forces. He wanted them to create a political movement against the provisional government. Both groups refused this idea. After another failed attempt to start a revolution, he decided to officially become an American citizen. He declared, “The United States sheltered me, The English didn’t care/what they owe they will pay/! I am citizen.” He then spent the next four years improving the conditions of the in any way he could.

Riel stayed in the United States from 1880-1884. He fought to get official residency from the American government. But without success, he finally left for Saskatchewan in 1884. Riel focused his public life on improving the situation of the Montana Métis. He had a big impact on the Métis people in the United States. He tried to address their rights and improve their living conditions. The following years were a constant struggle to get official American citizenship. In the end, American citizenship did not protect him from Canadian convictions. American officials did not confirm his American citizenship. They feared more conflict with the Canadian government. They confirmed Riel's execution for treason in 1885.

The Medicine Line (Canada–U.S. Border)

The Métis homeland existed before the Canada–U.S. border was created. It still exists on both sides of this border today. The border affected the Métis in many ways. Border control became stricter over time. In the late 1700s to early 1800s, the Métis found that they could cross the 49th parallel North to escape trouble. The trouble would stop once they crossed. So, the border was known as the Medicine Line. This began to change in the late 1800s. The border became more controlled. The Canadian government saw a chance to stop the border crossing. They used military force. This split some of the Métis population. It limited their movement. The border enforcement was used by governments on both sides to control the Métis. It also limited their access to buffalo. Because family ties and movement were so important to Métis communities, this had negative effects. It led to different challenges for both groups.

Métis experiences in the U.S. are largely shaped by treaties that were not approved. They also lack federal recognition of Métis communities as a real people. This can be seen with the Little Shell Tribe in Montana. While experiences in Canada also involve the misunderstanding of the Métis, many Métis lost their lands when they were sold to settlers. Some communities set up Road Allowance villages. These were small villages where people lived without permission on Crown land. They were outside established villages in the Canadian prairies. These villages were often burned by local authorities. The people who lived there had to rebuild them.

See also

In Spanish: Métis para niños

In Spanish: Métis para niños

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |