Mayan civilization facts for kids

The Maya civilization was a very old and important group of people who lived in Mesoamerica (a region in Central America and Mexico). They were known for their amazing cities, art, writing, and understanding of the stars. The Maya lived there for a long time, and some Maya people still live there today.

The Maya started living in this region about 4,000 years ago (around 2000 BC). Even back then, complex societies were forming. They grew important foods like maize (corn), beans, squashes, and chili peppers. The first Maya cities began to appear around 750 BC.

The Maya people had their own written language and a special number system. They were very skilled in art and building. Their priests studied the stars and planets, which helped them create very accurate calendars.

The Maya civilization was at its strongest between 420 AD and 900 AD. It stretched from central Mexico all the way to Honduras, Guatemala, and northern El Salvador. At its peak, it's thought that at least ten million people lived in the Maya civilization. They traded with other groups in the Americas, and their art and buildings show many different styles because of this trade. The Maya civilization started to become smaller after 900 AD.

When the Conquistadors (Spanish conquerors) arrived in the 15th century, they took over Mexico and later Central America, including Maya areas. However, the Maya people are still there today. They live in the same regions where the ancient Maya civilization once thrived. They still keep many of their old traditions and beliefs. Many Mayan languages are still spoken, like the Achi language. A famous play called Rabinal Achi is an important part of their culture.

Contents

Where the Maya Lived

The Maya civilization lived in three main areas: the southern Maya highlands, the central lowlands, and the northern lowlands. Their land had many different features, from mountains to dry plains. People living in the low plains near the sea sometimes faced hurricanes and tropical storms from the Caribbean.

The area they covered includes parts of what we now call the southern Mexican states of Chiapas and Tabasco, and the Yucatán Peninsula states of Quintana Roo, Campeche, and Yucatán. It also included modern-day Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, and western Honduras.

Maya History

Early Maya Period (Pre-Classic)

The first Maya settlements began around 1800 BC. They lived in the Soconusco region, which is now in Chiapas, Mexico, by the Pacific Ocean. This time is called the "early pre-classic period." Before this, people in Central America were nomads, meaning they moved from place to place to find food. Around this time, they started to settle down. They began farming, making pottery, and creating small clay figures. They buried their dead in simple burial mounds, which later grew into step pyramids.

Other cultures were also present, especially in the north. The Olmec, Mixe-Zoque, and Zapotec civilizations lived mostly in the area we now call Oaxaca. Many important early examples of writing and buildings appeared in the north, suggesting these cultures influenced the Maya.

Golden Age of the Maya (Classical Period)

From about 250 to 909 AD, the Maya civilization built many grand monuments and cities, and created beautiful carvings. The "southern lowlands" were a very important center for new ideas in art and thought during this time.

Like Ancient Greece, the Maya civilization was made up of many different city-states, each with its own way of working. People lived around these cities and farmed. Some well-known cities were Tikal, Palenque, Copán, and Calakmul. Other cities included Dos Pilas, Uaxactun, and Bonampak.

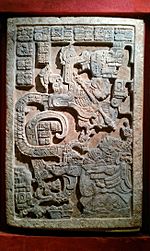

Their most famous buildings are the pyramids they built as part of their religious centers, and their large palaces. The palace at Cancuén is the biggest known in the Maya area. The Maya also made carved stone slabs called tetun, or "tree-stones." These slabs showed rulers and had hieroglyphic writing describing their family, military wins, and other achievements.

Trading with Neighbors

The Maya had long-distance trade routes. They traded with many other Mesoamerican cultures, like Teotihuacan and the Zapotec. They even traded with people farther away. For example, researchers found gold from Panama in the Sacred well at Chichen Itza.

Important trade items included cacao (for chocolate), salt, sea shells, jade, and obsidian (a volcanic glass).

The Maya Collapse

Between 900 AD and 1000 AD, the cities in the southern lowlands faced more and more problems until people started to leave. The Maya civilization there stopped building big monuments and carvings. Experts are not sure why this happened. They have many ideas: some think there was a major environmental disaster, a widespread disease, or simply too many people for the amount of food they could grow.

Later Maya Period (Post-Classical) and Spanish Arrival

In the north, the Maya civilization continued. Other cultures started to mix more with Mayan culture. Important sites during this time included Chichen Itza, Uxmal, Edzná, and Coba. At some point, the ruling families of Chichen Itza and Uxmal became weaker. The rulers in the city of Mayapan then controlled most of the Maya civilization in the Yucatán peninsula until a revolt in 1450. After the revolt, the area broke into many different cities that fought each other. This continued until the Spanish conquest of Yucatán.

The Itza Maya, Ko'woj, and Yalain groups around what is now Guatemala were still around, but their numbers were small. By 1520, they had grown again and started to build cities. The Itza had their capital at Tayasal. The Ko'woj had their capital at Zacpeten.

The Quiché kingdom created the most famous Maya book, the Popol Vuh. It tells about the creation of the world, the Maya gods and goddesses, and the history of the Kʼicheʼ kingdom.

The Spanish began to conquer Maya lands. It took them a long time (170 years) to finish because the Maya had no single capital city. Each city had its own culture. The last Maya states, the Itza city of Tayasal and the Ko'woj city of Zacpeten, were finally conquered in 1697.

Maya Society

From early times, Maya society was clearly divided between the rich elite and the common people. As the population grew, different parts of society became more specialized.

Kings and Their Courts

Classic Maya rule was centered around the king, who was seen as a very important, almost god-like figure. He was believed to connect the human world with the world of the gods. Kings were often linked to the young maize god. Royal power usually passed from father to eldest son.

Becoming king was a very detailed ceremony. It involved sitting on a jaguar-skin cushion, sometimes human sacrifice, and receiving symbols of royal power.

A Ajaw was usually a "lord" or "king." The most powerful kings were called kʼuhul ajaw, meaning "divine lord." A sajal was a lord who served an ajaw. Sajals were often war captains or regional governors.

Common People

Commoners made up over 90% of the Maya population. Their homes were usually made from materials that don't last, so little remains. Commoners did important work, like growing crops such as cotton and cacao for the elite, and food for themselves. They also made everyday items like pottery and stone tools. Commoners took part in wars and could rise in society by being great warriors. They paid taxes to the elite with goods like corn.

Maya Warfare

Warfare was common in the Maya world. Military campaigns were started for many reasons, including controlling trade routes, collecting tribute, taking captives, or completely destroying an enemy state. Maya art and writings show wars and victories.

In the 8th and 9th centuries, intense warfare led to the collapse of kingdoms in the Petexbatún region. The city of Aguateca was quickly abandoned around 810 AD after enemies attacked and burned the royal palace. This shows how intense warfare could be.

From early times, a Maya ruler was expected to be a strong war leader. Classic period kings are often shown standing over captured enemies. Even up to the Spanish conquest, Maya kings led their armies. Maya writings show that a defeated king could be captured and sacrificed.

Warriors and Weapons

Military roles were often held by nobles and passed down through families. Maya armies were well-trained, and warriors practiced regularly. Every able-bodied adult male was ready for military service. Maya states did not have standing armies. Most warriors were not full-time soldiers; they were mainly farmers. Maya warfare was often aimed at taking captives and loot.

The atlatl (spear-thrower) was brought to the Maya region in the Early Classic period. It helped launch darts or javelins with more force. Darts and spears were the main weapons. Commoners used blowguns. The bow and arrow was used for both war and hunting, but became common in war only in the Postclassic period. The Maya also used two-handed swords made of wood with sharp obsidian blades.

Maya warriors wore body armor made of quilted cotton soaked in salt water to make it tough. This armor was as good as the steel armor worn by the Spanish. Warriors carried wooden or animal hide shields.

Maya Art

Maya art was mainly for the royal court and focused on the Maya elite. It was made from both materials that last (like stone) and those that don't (like wood). Maya art helped connect the living Maya to their ancestors. The best surviving Maya art is from the Late Classic period.

The Maya preferred the color green or blue-green. They highly valued apple-green jade and other greenstones, linking them to the sun-god Kʼinich Ajau. They carved items like beads and heads. Jade mosaic masks were also made for burials, like the one for King Kʼinich Janaabʼ Pakal of Palenque.

Maya stone sculpture appeared already well-developed. Stone Maya stelae are common in city sites, often with low, round stones called altars. Stone sculpture also included relief panels. At other sites, stone stairways were decorated with carvings. The hieroglyphic stairway at Copán has the longest surviving Maya text.

The largest Maya sculptures were building fronts made from stucco (a type of plaster). Giant stucco masks were used to decorate temple fronts from the Late Preclassic period and continued into the Classic period.

The Maya had a long history of painting murals. Rich, colorful murals have been found at San Bartolo, dating from 300 to 200 BC. Walls were covered with plaster, and colorful designs were painted. Some of the best-preserved murals are a full series of Late Classic paintings at Bonampak.

Flint, chert, and obsidian were used for tools, but many pieces were also beautifully crafted into shapes not meant for use. Eccentric flints are some of the finest stone items made by the ancient Maya.

Maya textiles (woven fabrics) are rarely found in archaeological sites. However, they were probably very valuable. The best evidence for textiles comes from how they are shown in murals or on pottery. These images show Maya court members wearing rich clothes, usually cotton, but also jaguar pelts.

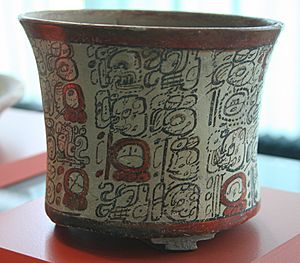

Ceramics (pottery) are the most common type of Maya art that has survived. The Maya did not use the potter's wheel. Instead, they built vessels by coiling rolled strips of clay. Many very fine ceramic figurines have been found in Late Classic tombs on Jaina Island. They are 10 to 25 centimeters (4 to 10 inches) tall and were shaped by hand with amazing detail.

Bone, both human and animal, was also carved. The Maya valued Spondylus shells and carved them. Around the 10th century AD, metalworking arrived, and the Maya started making small items from gold, silver, and copper. They usually hammered sheet metal.

A less studied area of Maya art is graffiti. This was extra art carved into the stucco of inner walls, floors, and benches in many buildings. Graffiti has been found at 51 Maya sites.

Maya Architecture

The Maya built many different kinds of structures and left behind a huge architectural legacy. Maya buildings also included various art forms and hieroglyphic texts. The stone buildings show that Maya society had specialized workers and organized planning.

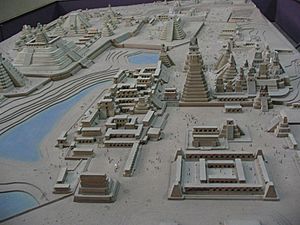

City Design

Maya cities were not formally planned. They grew in an irregular way, with palaces, temples, and other buildings added over time. The centers of all Maya cities had sacred areas, sometimes separated from nearby homes by walls. These areas contained pyramid temples and other large buildings for elite activities. City centers also had plazas, sacred ballcourts, and buildings for markets and schools. Roads often connected the center to outer parts of the city.

The ceremonial center of a Maya city was where the ruling elite lived and where the city's government and religious ceremonies took place. It was also where people gathered for public events. Elite homes were on the best land near the city center, while commoners lived farther away. Homes were built on stone platforms to raise them above floodwaters.

Building Materials and Methods

The Maya built their cities using technology from the Stone Age. They used both materials that decay and stone. The type of stone used depended on what was available locally. Limestone was easy to find in many areas. At Copán, volcanic rock was used, and nearby Quiriguá used sandstone. At Comalcalco, where stone was scarce, they used fired bricks.

Limestone was burned to make cement, plaster, and stucco. Lime-based cement was used to hold stonework in place. The Maya did not use a functional wheel, so all heavy loads were carried by porters or on boats.

Wood was used for beams and door frames, even in stone buildings. Simple huts and some temples continued to be built from wooden poles and thatch. Adobe (mud mixed with straw) was also used to cover the woven-stick walls of huts.

Main Building Types

The great cities of the Maya civilization had pyramid temples, palaces, ballcourts, sacbeob (raised roads), patios, and plazas. Some cities also had large water systems or defensive walls. The outside of most buildings was painted. Many buildings were decorated with sculptures or painted stucco reliefs.

Palaces and Acropolises

These large complexes were usually in the city center. Maya palaces were platforms supporting multi-room buildings. An acropolis in Maya terms means a group of buildings on platforms of different heights. Palaces and acropolises were mainly homes for the elite. They usually spread out horizontally and often had limited access. Some buildings had roof combs (tall structures on the roof). Rooms often had stone benches for sleeping. Large palaces could have a water supply, and sweat baths were often found nearby.

Palaces were usually built around one or more courtyards. Many palaces have writings that say they were the royal homes of specific rulers. Many court activities took place in them, including meetings and important rituals.

Pyramids and Temples

Temples were sometimes called kʼuh nah, meaning "god's house." Temples were built on platforms, most often on a pyramid. The earliest temples were probably thatched huts. By the Late Preclassic period, their walls were of stone, and the corbel arch allowed stone roofs to replace thatch. By the Classic period, temple roofs had tall roof combs. Temple shrines contained one to three rooms and were dedicated to important gods or deified ancestors.

E-Groups and Observatories

The Maya were careful observers of the sun, stars, and planets. E-Groups were a special arrangement of temples common in the Maya region. They were used to mark the solstices and equinoxes. The earliest ones are from the Preclassic period. From the west pyramid, the sun was seen to rise over the three small temples on the other side during the solstices and equinoxes.

Besides E-Groups, the Maya built other structures to observe celestial bodies. Many Maya buildings were aligned with astronomical objects, including the planet Venus. The Caracol building at Chichen Itza was a circular building with slit windows that marked the movements of Venus.

Triadic Pyramids

Triadic pyramids first appeared in the Preclassic. They had a main structure with two smaller buildings facing inwards, all on one large platform. The triadic form was the main architectural form in the Petén region during the Late Preclassic. Examples are found at many archaeological sites. The triadic pyramid remained popular for centuries, even into the Classic Period. The triple-temple shape of the triadic pyramid seems to be connected to Maya mythology.

Ballcourts

The ballcourt is a special type of building found across Mesoamerica. Most Maya ballcourts are from the Classic period. They had a characteristic "I" shape, with a central playing area ending in two side zones. The central playing area was usually 20 to 30 meters (66 to 98 feet) long. The Great Ballcourt at Chichen Itza is the largest in Mesoamerica.

Maya Language

Before 2000 BC, the Maya spoke a single language, which experts call proto-Mayan. This language later split into the many different Mayan languages we know today. The language found in almost all Classic Maya texts is called Chʼolan. This might have been a special language used by the elite for important writings and communication between cities. By the Postclassic period, Yucatec was also being written in Maya books.

Writing and Literacy

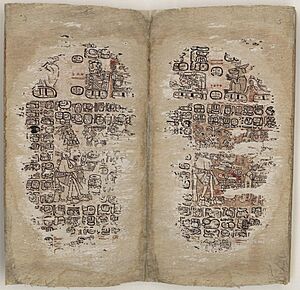

The Maya writing system is one of the greatest achievements of ancient American people. It was the most advanced writing system among the many that developed in Mesoamerica. The earliest Maya writings found date back to 300–200 BC. By about 250 AD, the Maya script became a more formal writing system.

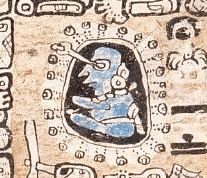

The Catholic Church and Spanish officials destroyed Maya texts. However, four original pre-Columbian books from the Postclassic period have survived. These are known as the Madrid Codex, the Dresden Codex, the Paris Codex, and the Maya Codex of Mexico.

Most surviving ancient Maya writing is from the Classic period and is found on stone monuments or on pottery. Other writings are on stucco walls, frescoes, wooden door frames, and small items.

How Maya Writing Works

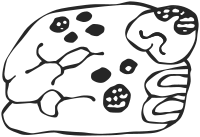

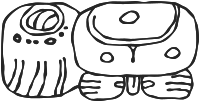

The Maya writing system (often called hieroglyphs) combines symbols that represent whole words (logograms) with symbols that represent syllables. About 500 symbols were used, with about 200 of them being phonetic (representing sounds).

The Maya script was used until the Europeans arrived. More than 10,000 individual texts have been found, mostly carved on stone monuments and pottery. The Maya also wrote texts on a type of paper made from tree bark, used to make codices (books). The knowledge of Maya writing was later lost due to the Spanish conquest.

Understanding Maya writing has been a long process. Some parts were first understood in the late 1800s. Big breakthroughs happened from the 1950s to the 1970s. By the end of the 20th century, experts could read most Maya texts.

Scribes and Reading

Common people could not read or write. Scribes (people who wrote) came from the elite class. Some women could write, as Maya art shows female scribes. There were probably schools where young nobles learned to write.

Some scribes signed their work on pottery and stone sculptures.

Maya Mathematics

Like other Mesoamerican civilizations, the Maya used a base-20 (vigesimal) number system. The bar-and-dot counting system was used by 1000 BC. The Maya adopted it and added a symbol for zero. This might have been the earliest known use of an explicit zero in the world.

The basic number system uses a dot for one and a bar for five. A shell symbol represented zero. The value of a number depended on its position. As a number moved up, its value multiplied by twenty. So, the lowest symbol was for units, the next for multiples of twenty, and the symbol above that for multiples of 400. For example, 884 would be written with four dots on the lowest level (4x1), four dots on the next level up (4x20), and two dots on the level above that (2x400).

Maya Calendar

The Maya calendar system, like other Mesoamerican calendars, started in the Preclassic period. The Maya developed it to be very accurate, recording cycles of the moon and sun, eclipses, and planet movements. In some cases, Maya calculations were more accurate than those in Europe at the time. The Maya calendar was deeply connected to Maya rituals.

The calendar combined a non-repeating Long Count with three repeating cycles. These were the 260-day tzolkʼin, the 365-day haabʼ, and the 52-year Calendar Round, which combined the tzolkʼin and the haab'.

The basic unit in the Maya calendar was one day, or kʼin. Twenty kʼin made a winal. The next unit was multiplied by 18 to get a rough solar year (360 days). This 360-day year was called a tun. Each level after that followed the base-20 system.

| Period | Calculation | Span | Years (approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| kʼin | 1 day | 1 day | |

| winal | 1 x 20 | 20 days | |

| tun | 20 x 18 | 360 days | 1 year |

| kʼatun | 20 x 18 x 20 | 7,200 days | 20 years |

| bakʼtun | 20 x 18 x 20 x 20 | 144,000 days | 394 years |

The 260-day tzolkʼin was the main cycle for Maya ceremonies and prophecies. It repeated a series of 20-day names, with a number from 1 to 13.

The 365-day haab was made of eighteen named 20-day winals, plus a 5-day period called the wayeb. The wayeb was thought to be a dangerous time.

The Maya measured time from a fixed starting point, which they believed was the creation of the world in its current form, equivalent to a day in 3114 BC.

Maya Astronomy

The Maya carefully observed celestial bodies. This information was used for divination (predicting the future). It also had practical uses, like helping with planting and harvesting crops. Priests recorded eclipses of the sun and moon, and the movements of Venus and the stars. They compared these to past events, believing similar events would happen again.

The Maya measured the 584-day Venus cycle with great accuracy. Solar and lunar eclipses were considered very dangerous events. In the Dresden Codex, a solar eclipse is shown as a serpent eating the kʼin ("day") symbol. Lunar tables were recorded so the Maya could predict them and perform ceremonies to prevent disaster.

Religion and Mythology

Like other Mesoamerican cultures, the Maya believed in a supernatural world filled with powerful gods who needed offerings and rituals. At the heart of Maya religion was the worship of dead ancestors, who were believed to help their living family members.

The Maya saw the universe as very structured. There were thirteen levels in the heavens and nine in the underworld, with the human world in between. Each level had four directions, each linked to a different color.

Maya families buried their dead under their house floors, with offerings. The dead could then act as protective ancestors. As Maya society grew, royal families turned their shrines into the great pyramids that held the tombs of their ancestors.

Belief in supernatural forces touched every part of Maya life. The Maya priesthood was a closed group, with members from the elite. Priests performed public ceremonies that included feasting, bloodletting, burning incense, music, ritual dancing, and, on certain occasions, human sacrifice. During the Classic period, the Maya ruler was the high priest and the direct link between humans and the gods.

Maya Gods

The Maya world was full of many gods and spirits. The importance of a god and its features changed with the movement of celestial bodies. Each god had four forms, linked to the four directions and a different color.

Itzamna was the creator god and also a sun god. Kʼinich Ahau, the day sun, was one of his forms. Itzamna also had a night sun form, the Night Jaguar. The four Pawatuns supported the corners of the human world. The four Chaacs were storm gods, controlling thunder, lightning, and rain. Other important gods included the moon goddess, the maize god, and the Hero Twins.

The Popol Vuh tells the mythical creation of the world, the story of the Hero Twins, and the history of the Kʼicheʼ kingdom.

Like other Mesoamerican cultures, the Maya worshipped feathered serpent deities. In Yucatán, the feathered serpent god was Kukulkan. Among the Kʼicheʼ, it was Qʼuqʼumatz.

Maya Agriculture

The ancient Maya had many different and advanced ways of producing food. It is now thought that permanent raised fields, terracing, intensive gardening, forest gardens, and managed fallows (leaving land unplanted for a time) were very important for supporting the large populations.

The main foods of the Maya diet were maize (corn), beans, and squashes. These were added to with many other plants grown in gardens or gathered from the forest, like chilies and tomatoes. The Maya also grew valuable crops like cotton, cacao (for chocolate), and vanilla.

The Maya had few domesticated animals. Dogs were domesticated by 3000 BC, and the Muscovy duck by the Late Postclassic. Ocellated turkeys were caught in the wild and kept in pens to be fattened. All of these animals were used for food. Dogs were also used for hunting.

Important Maya Sites

There are hundreds of Maya sites spread across five countries: Belize, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico. The six sites with especially amazing architecture or sculpture are Chichen Itza, Palenque, Uxmal, and Yaxchilan in Mexico, Tikal in Guatemala, and Copán in Honduras. Other important sites include Calakmul and El Mirador. The main sites in the Puuc region, after Uxmal, are Kabah, Labna, and Sayil. In the east of the Yucatán Peninsula are Coba and the small site of Tulum. The Río Bec sites include Becan, Chicanná, and Xpuhil. The most notable sites in Chiapas, other than Palenque and Yaxchilan, are Bonampak and Toniná. In the Guatemalan Highlands are Iximche, Kaminaljuyu, and Qʼumarkaj. In the northern Petén lowlands of Guatemala, there are many sites, though access is generally difficult apart from Tikal. Important sites in Belize include Altun Ha, Caracol, and Xunantunich.

Maya Collections in Museums

Many museums around the world have Maya artifacts in their collections. The Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies lists over 250 museums in its Maya Museum database. The European Association of Mayanists lists almost 50 museums in Europe alone.

Images for kids

-

Remains in Joya de Cerén, a Classic-era settlement in El Salvador buried under volcanic ash around 600 AD. Its preservation has greatly helped in the study of everyday life in a Maya farming community.

-

Stela D from Quiriguá, representing king Kʼakʼ Tiliw Chan Yopaat.

-

Chichen Itza was the most important city in the northern Maya region.

-

Mayapan was an important Postclassic city in the northern Yucatán Peninsula.

-

A page from the Lienzo de Tlaxcala showing the Spanish conquest of Iximche.

-

A drawing by Frederick Catherwood of the Nunnery complex at Uxmal.

-

An 1892 photograph of the Castillo at Chichen Itza, by Teoberto Maler.

See also

In Spanish: Cultura maya para niños

In Spanish: Cultura maya para niños