Great bustard facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Great bustard |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Otis

|

| Species: |

tarda

|

|

|

| Range of Otis tarda Breeding Resident Passage Non-breeding | |

The great bustard (Otis tarda) is a very large bird. It belongs to the bustard family. This bird is the only living member of its group, called Otis.

Great bustards live in open grasslands and farms. You can find them from northern Morocco across southern and Central Europe to parts of Central and East Asia. Birds in Europe usually stay in one place. However, those in Asia fly south for the winter. As of 2023, the great bustard is an endangered bird. It has been on the IUCN Red List as a Vulnerable species since 1996.

Today, about 60% of all great bustards live in Portugal and Spain. The bird disappeared from Great Britain in 1832. This happened when the last one was shot. Since 1998, a group called The Great Bustard Group has worked to bring them back to England. They are being reintroduced on Salisbury Plain. This area is used by the British Army. It offers the birds the quiet space they need. This is important for a large bird that nests on the ground.

Contents

About the Great Bustard's Name

The name Otis for this bird group was first used in 1758. It was given by a Swedish scientist named Carl Linnaeus. He wrote about it in his book Systema Naturae. The name comes from an old Greek word, ōtis. This word was used for a similar bird in ancient texts.

The second part of the name, tarda, is Latin. It means "slow" or "deliberate." This describes how the bird usually walks. The word "bustard" itself comes from the Latin phrase avis tarda, meaning "slow bird."

What Does a Great Bustard Look Like?

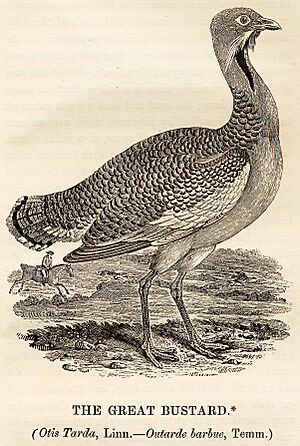

The adult male great bustard is one of the heaviest flying birds in the world. A male is usually about 90 to 105 centimeters (3 to 3.5 feet) tall. Its body length is around 115 centimeters (3.8 feet). Its wings can spread out 2.1 to 2.7 meters (7 to 9 feet) wide.

Males can weigh from 5.8 to 18 kilograms (13 to 40 pounds). The heaviest one ever recorded weighed about 21 kilograms (46 pounds). This is a world record for the heaviest flying bird! In Spain, some males have weighed as much as 19 kilograms (42 pounds).

Great bustards show a big difference in size between males and females. This is called sexual dimorphism. Male great bustards in Spain weigh about 2.5 times more than females.

Females are smaller. They are typically 75 to 85 centimeters (2.5 to 2.8 feet) tall. Their body length is about 90 centimeters (3 feet). Their wingspan is around 180 centimeters (6 feet). Females weigh from 3.1 to 8 kilograms (7 to 18 pounds).

An adult male has a brown back with black stripes. Its belly is white. It has a long grey neck and head. Its chest and lower neck are a chestnut color. The bright colors on its back become stronger as the male gets older.

During the breeding season, males grow long white feathers on their neck. These can be 12 to 15 centimeters (5 to 6 inches) long. They keep growing from the bird's third to sixth year. When flying, their long wings are mostly white. They have brown edges on the lower feathers and a dark brown stripe on the upper edge.

The female's chest and neck are buff-colored. The rest of her feathers are brown and pale. This helps her blend in with her surroundings. Young birds look like the female. The great bustard has long legs, a long neck, and a heavy body. Its shape and preferred habitat are typical for bustards.

Where Great Bustards Live

These birds live in grasslands or steppes. These are open, flat, or slightly rolling landscapes. They like areas with wild or farmed plants like cereals, grapes, and fodder plants. However, during breeding season, they avoid places with a lot of human activity. Farm work can disturb them. Great bustards are often found where there are many insects.

Today, great bustards breed from Portugal to Manchuria. More than half of all great bustards live in central Spain. There are about 30,000 birds there. Smaller groups live in southern Russia and Hungary.

Great Bustard Behavior and Life

Great bustards like to be in groups, especially in winter. Groups of males and females do not mix outside of the breeding season. The great bustard walks slowly and with dignity. But if it feels threatened, it usually runs instead of flying. Females have been seen outrunning red foxes. Foxes can trot at 48 kilometers per hour (30 mph).

Both male and female bustards are usually quiet. But they can make deep grunting sounds if they are scared or angry. Males performing their mating display might make booming, grunting, and loud noises. Females might make soft calls at the nest. Young chicks make a soft, trilling sound to talk to their mothers.

Migration

Some great bustards in Spain move short distances, about 5 to 200 kilometers (3 to 124 miles). Males seem to move more when summer temperatures are high. European groups either stay in one place or move if winter weather is very bad.

Bustards that breed in Russia fly about 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) south for winter. Birds from northern Mongolia fly over 2,000 kilometers (1,240 miles) to China. Great bustards often gather in large numbers before they migrate. This helps them move together to their winter homes. They are strong fliers and can reach speeds of 48 to 98 kilometers per hour (30 to 61 mph) when migrating.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Great bustards breed in March. Before mating, males change their feathers around January. Males show who is strongest in their groups during winter. They might fight by ramming and hitting each other with their beaks.

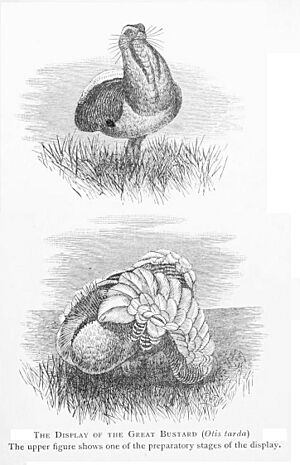

Like other bustards, male great bustards show off to attract females. This happens in a special area called a lek. The male's display is very showy. He puffs up his throat to the size of a football. Then he leans forward and pulls his head in. His long, whiskery chin feathers point upwards, and his head disappears. He then flattens his tail along his back. This shows off his bright white feathers that are usually hidden. He also lowers his wings, fanning out the white feathers. Displaying males can walk around like this for several minutes. They wait for females to arrive. People have said they look like a "foam-bath" when they display.

The female lays one to three glossy, olive or tan-colored eggs. Two eggs are most common. This happens in May or June. The nests are shallow scrapes made by the female. They are usually on dry, soft slopes or plains, close to where the males displayed. Nests are often found in small groups. One study found nests only 9 meters (30 feet) apart. Nests are usually in thick grass, about 15 to 35 centimeters (6 to 14 inches) tall. This helps protect them from predators.

The eggs weigh about 150 grams (5.3 ounces). They are about 79.4 millimeters (3.1 inches) tall and 56.8 millimeters (2.2 inches) wide. The female sits on the eggs alone for 21 to 28 days. The chicks leave the nest almost right after hatching. But they stay close to their mother until they are at least 1 year old.

Young great bustards start to get their adult feathers at about 2 months old. They also start learning to fly then. They practice by stretching, running, flapping, and making small jumps. By three months, they can fly good distances. If they feel threatened, young birds stand still. Their brown and pale streaked feathers help them hide.

Young bustards can live on their own by their first winter. But they usually stay with their mother until the next breeding season. Males usually start mating when they are 5 to 6 years old. Females usually breed for the first time when they are 2 to 3 years old.

What Great Bustards Eat

Great bustards eat both plants and animals. This means they are omnivores. Their diet changes with the seasons. In Spain, in August, adult birds ate mostly green plants (48.4%). They also ate invertebrates (40.9%) and seeds (10.6%). In winter, they mostly ate seeds and green plants. They seem to like Alfalfa. Other favorite plants include legumes, cabbage-like plants, dandelions, and grapes. They also eat dry seeds from wheat and barley.

insects are a main food for young bustards in their first summer. They then switch to eating plants like the adults in winter. They mostly eat beetles, ants, and grasshoppers. Small vertebrates are also eaten if they get the chance. Great bustards sometimes eat poisonous blister beetles. They might do this to help themselves with parasites.

How They Find Food

In winter, both male and female bustards eat more in the morning. Males eat less intensely than females. But males can make up for this by eating for longer periods. They also take bigger bites. This helps them get enough food for their larger size.

Dangers and Lifespan

Great bustards usually live for about 10 years. Some have lived for 15 years or more. The longest known life for a great bustard was 28 years. Adult males seem to die more often than females. This is mainly because of fierce fights with other males during breeding season. Many males might die in their first few years of being adults because of these fights.

More than 80% of great bustards die in their first year of life. Many are caught by predators. Chicks are easy targets because they live on the ground and don't like to fly. Predators of eggs and young chicks include raptors, corvids (like crows), hedgehogs, foxes, weasels, badgers, martens, rats, and wild boars. Red foxes and hooded crows are probably the biggest threats to nests.

Chicks grow very fast. By 6 months, they are almost two-thirds of their adult size. They can be hunted by foxes, lynxes, gray wolves, dogs, jackals, and eagles. Adult male great bustards have been hunted by white-tailed eagles. Golden eagles are also possible predators. Eastern imperial eagles have been known to hunt great bustards.

Predation is generally rare for adult bustards. This is because they are large, quick, and safer in groups. Sometimes, natural causes like starvation in harsh winters can also lead to death. However, in recent centuries, most deaths have been due to human activities.

Where Great Bustards Are Found Today

In 2008, there were about 44,000 to 51,000 great bustards worldwide. About 38,000 to 47,000 were in Europe. More than half of them, about 30,000, were in Spain. Hungary had the next largest group, with about 1,555 birds in 2012. Ukraine and Austria followed. About 4,200 to 4,500 were in East Asia.

In recent times, numbers have dropped sharply in eastern and central Europe and in Asia. This is especially true in Kazakhstan and Mongolia.

| Presence | Countries |

|---|---|

| Native | Afghanistan, Armenia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, China, Croatia, Czech Republic, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iran, Iraq, Italy, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Mongolia, Montenegro, Morocco, North Macedonia, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Spain, Syria, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, United Kingdom, Uzbekistan |

| Regionally extinct | Algeria, Lithuania, Myanmar, Poland, Sweden, Switzerland, Kyrgyzstan |

| Vagrant | Albania, Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Egypt, Finland, Gibraltar, Ireland, Israel, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia |

| Presence uncertain | Lebanon, Pakistan |

Large groups of great bustards live in Spain (23,055 birds), Russia (8,000 birds), Turkey (800–3,000 birds), Portugal (1,435 birds), and Mongolia (1,000 birds). In Germany and Austria, the groups are small. But they have been slowly growing for about 20 years. In other places, their numbers are falling. This is due to losing their natural homes.

In Hungary, there are 1,100–1,300 birds. This is where the Eastern European steppe zone ends. This group is down from 10,000–12,000 birds before World War II.

Threats and Conservation Efforts

The great bustard is considered vulnerable. Many things threaten these birds. More human activity can lead to losing their homes. This includes plowing grasslands, intense farming, planting forests, and building roads, power lines, fences, and ditches.

Machines, chemical fertilizers, and pesticides are big dangers for chicks and young birds. Hunting adults also causes many deaths in some countries. Farm work is a major disturbance at nests. In Hungary, few nests succeed outside of protected areas.

Bustards can fly very fast. But they are often hurt or killed by overhead electricity cables. These cables are at their flying height in parts of Austria and Hungary. Electricity companies have buried some dangerous cables. They have also marked remaining overhead wires with bright markers. This helps warn the birds. These actions have quickly reduced bustard deaths. Bustards are also sometimes killed by cars or by getting tangled in wires.

The great bustard used to live in Great Britain. A bustard is even part of the design on the Wiltshire Coat of Arms. In 1797, a naturalist named Thomas Bewick wrote about his concerns. He worried that the great bustard would disappear from Britain. He was right. The great bustard was hunted out of existence in Britain by the 1840s.

In 2004, The Great Bustard Group started a project. They are bringing great bustards back to Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire. They use eggs from Russia. This group is a UK charity. Their goal is to create a self-sustaining group of great bustards in the UK. The reintroduced birds have laid eggs and raised chicks in Britain since 2009.

Even though the great bustard was once native to Britain, it is considered an "alien species" under English law. The Great Bustard Group works with researchers from the University of Bath. These researchers study bustard homes in Russia and Hungary. In 2011, the Great Bustard Project received a large grant to help their work. By 2020, the group in Wiltshire had more than 100 birds.

In Hungary, the great bustard is the national bird. They are actively protected there. Hungarian authorities are working to protect the birds for the long term. They use special ecological treatments in an area that grew to 15 square kilometers (5.8 sq mi) by 2006.

An agreement called the Great Bustard Memorandum of Understanding helps protect great bustards. It started in 2001. This agreement helps governments, scientists, and conservation groups work together. They monitor and coordinate efforts to protect the great bustard in central Europe.

Images for kids