Alfred the Great facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Alfred the Great |

|

|---|---|

A silver coin of Alfred

|

|

| King of the West Saxons later King of the Anglo-Saxons |

|

| Reign | April 871 – October 899 |

| Predecessor | Æthelred |

| Successor | Edward the Elder |

| Born | 848–49 Wantage, Berkshire |

| Died | 26 October 899 (aged 50 or 51) |

| Burial | c. 1100 Hyde Abbey, Winchester, Hampshire, now lost |

| Spouse | Ealhswith |

| Issue | |

| House | Wessex |

| Father | Æthelwulf, King of Wessex |

| Mother | Osburh |

Alfred the Great (also known as Ælfred) was a powerful king who ruled the West Saxons from 871 to about 886. Later, he became the King of the Anglo-Saxons until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh. Both of Alfred's parents died when he was young.

Before Alfred, three of his older brothers—Æthelbald, Æthelberht, and Æthelred—ruled the kingdom. Alfred made big changes to how his kingdom was run and how its army worked. These changes had a lasting impact on England.

When Alfred became king, he spent many years fighting against Viking invaders. He won a very important battle called the Battle of Edington in 878. After this victory, he made a deal with the Vikings. This agreement divided England into two parts: Anglo-Saxon land and the Danelaw, which was ruled by Vikings. The Danelaw included northern England, the northeast Midlands, and East Anglia.

Alfred also convinced the Viking leader Guthrum to become a Christian. He successfully defended his kingdom from Viking attacks and became the most important ruler in England. We know a lot about Alfred's life from a book written by Asser, a Welsh scholar and bishop from the 9th century.

Alfred was known as a wise and kind ruler. He was calm and fair. He strongly supported education and thought that children should learn in Old English instead of Latin. He also made improvements to the laws and the army, which helped improve the lives of his people. People started calling him "the Great" in the 16th century, long after he died.

Contents

- Alfred's Early Life and Family

- Battles During His Brothers' Reigns

- Alfred Becomes King and Fights On

- Alfred's Military Changes

- Alfred's Legal Reforms

- Alfred's Foreign Relations

- Alfred's Focus on Religion and Culture

- Alfred's Appearance and Personality

- Alfred's Family Life

- Alfred's Death and Burial

- Alfred's Lasting Legacy

- Statues Honoring Alfred

- Images for kids

- See also

Alfred's Early Life and Family

Alfred was born in a village called Wanating, which is now Wantage, in Oxfordshire. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf of Wessex and his first wife, Osburh.

In 853, when Alfred was four years old, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says he was sent to Rome. There, Pope Leo IV confirmed him and "anointed him as king." Some writers later thought this meant he was being prepared to become king of Wessex. However, this was unlikely because Alfred had three older brothers who were still alive. A letter from Pope Leo IV shows that Alfred was made a "consul," which might explain the confusion. Alfred also went with his father on a trip to Rome around 854–855. During this trip, he spent some time at the court of Charles the Bald, the King of the Franks.

When Alfred and his father returned from Rome in 856, Æthelwulf was removed from power by his son Æthelbald. To avoid a civil war, the important people of the kingdom met and decided to share power. Æthelbald would rule the western parts of Wessex, and Æthelwulf would rule the eastern parts. After King Æthelwulf died in 858, Wessex was ruled by Alfred's three older brothers: Æthelbald, Æthelberht, and Æthelred.

Bishop Asser tells a story about Alfred's childhood. His mother offered a book of Saxon poems as a prize to the first of her children who could memorize it. Alfred won the prize. There's also a legend that young Alfred went to Ireland to seek healing for his health problems. Alfred suffered from health issues throughout his life, and some think he might have had Crohn's disease. Statues of Alfred in Winchester and Wantage show him as a great warrior. However, historical evidence suggests he wasn't physically strong. He was known more for his intelligence than for being a fierce fighter.

Battles During His Brothers' Reigns

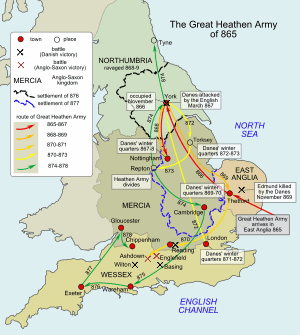

Alfred is not mentioned much during the short reigns of his two oldest brothers, Æthelbald and Æthelberht. His public life really began when his third brother, Æthelred, became king in 865. This was when a large army of Danes, called the Great Heathen Army, arrived in East Anglia. They wanted to conquer the four Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in England.

During this time, Bishop Asser called Alfred a secundarius. This might mean he was like a recognized successor, closely linked to the king. This plan might have been set up by Alfred's father or by the Witan (a council of wise men). It would help prevent arguments over who would be king if Æthelred died in battle. It was common for other Germanic groups, like the Swedes and Franks, to crown a successor as a royal prince and military leader.

Fighting the Viking Invasion

In 868, Alfred fought alongside Æthelred to try and keep the Great Heathen Army out of the nearby Kingdom of Mercia. They were not successful. By the end of 870, the Danes had reached Alfred's homeland. The next year was called "Alfred's year of battles." Nine battles were fought, with different results. We don't know the exact places and dates for two of them.

In Berkshire, the Saxons had a small victory at the Battle of Englefield on December 31, 870. But then they suffered a big defeat at the siege and Battle of Reading on January 5, 871. This battle was led by Halfdan Ragnarsson, a brother of the Viking leader Ivar. Four days later, the Anglo-Saxons won a great victory at the Battle of Ashdown. This battle was fought on the Berkshire Downs, possibly near Compton or Aldworth. Alfred is especially praised for his role in this victory.

Later that month, on January 22, the Saxons were defeated at the Battle of Basing. They lost again on March 22 at the Battle of Merton. King Æthelred died soon after, on April 23.

Alfred Becomes King and Fights On

Early Challenges and Retreat

In April 871, King Æthelred died, and Alfred became king of Wessex. He also took on the difficult job of defending the kingdom. This happened even though Æthelred had two young sons, Æthelhelm and Æthelwold. This was part of an agreement Alfred and Æthelred had made earlier that year. They had agreed that the brother who lived longer would inherit their father's property. The dead brother's sons would only get what their father had left them. This meant the surviving brother would become king. Because of the ongoing Danish invasion and his nephews' young age, Alfred becoming king likely went smoothly.

While Alfred was busy with his brother's funeral, the Danes defeated the Saxon army in his absence. Then, they defeated him again at Wilton in May. This defeat at Wilton crushed any hope Alfred had of driving the invaders out of his kingdom. He was forced to make peace with them, though the exact terms of this peace are not known. Bishop Asser said that the Vikings agreed to leave Wessex and kept their promise.

The Viking army did move from Reading in the autumn of 871 to spend the winter in London, which was part of Mercia. Although Asser and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle don't mention it, Alfred probably paid the Vikings money to leave. The Mercians did the same thing the next year. Hoards of treasure found in Croydon, Gravesend, and Waterloo Bridge from the Viking stay in London in 871-872 suggest how costly it was to make peace with them. For the next five years, the Danes occupied other parts of England.

In 876, under their new leader, Guthrum, the Danes secretly moved past the Saxon army. They attacked and took over Wareham in Dorset. Alfred surrounded them but couldn't capture Wareham by force. So, he made a peace deal. This involved exchanging hostages and the Danes swearing oaths on a "holy ring" linked to the god Thor. However, the Danes broke their promise. After killing all the hostages, they slipped away at night to Exeter in Devon.

Alfred then surrounded the Viking ships in Devon. When a Viking relief fleet was scattered by a storm, the Danes had to surrender. They then moved to Mercia. In January 878, the Danes suddenly attacked Chippenham, a royal stronghold where Alfred had been staying for Christmas. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says, "most of the people they killed, except the King Alfred, and he with a little band made his way by wood and swamp, and after Easter he made a fort at Athelney in the marshes of Somerset, and from that fort kept fighting against the foe." From his fort at Athelney, an island in the marshes near North Petherton, Alfred was able to lead a strong resistance. He gathered local militias from Somerset, Wiltshire, and Hampshire.

A famous legend, which started in the 12th century, tells how Alfred, when he first fled to the Somerset Levels, was given shelter by a peasant woman. She didn't know who he was and asked him to watch some cakes cooking on the fire. Alfred was so worried about his kingdom that he accidentally let the cakes burn. The woman then scolded him angrily when she returned.

The year 878 was a very difficult time for the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. All the other kingdoms had fallen to the Vikings, and only Wessex was still fighting.

Alfred's Counter-Attack and Victory

Seven weeks after Easter in 878, around Whitsuntide, Alfred rode to 'Egbert's Stone' east of Selwood. There, he was met by "all the people of Somerset and of Wiltshire and of that part of Hampshire which is on this side of the sea (that is, west of Southampton Water), and they rejoiced to see him." Alfred coming out of his marsh hideout was part of a carefully planned attack. He gathered the armies (called fyrds) from three different areas. This showed that the king still had the loyalty of his important leaders and officials. It also showed that these leaders had kept their power in their areas well enough to answer his call to war. Alfred's actions also suggest he had a system of scouts and messengers.

Alfred won a major victory in the Battle of Edington, which might have been fought near Westbury, Wiltshire. He then chased the Danes to their stronghold at Chippenham and starved them until they surrendered. One of the terms of their surrender was that Guthrum, the Viking leader, had to become a Christian. Three weeks later, Guthrum and 29 of his main men were baptized at Alfred's court in Aller, near Athelney. Alfred became Guthrum's spiritual father.

According to Asser, the formal ceremony for Guthrum's baptism took place eight days later at the royal estate at Wedmore. While at Wedmore, Alfred and Guthrum discussed what some historians call the Treaty of Wedmore. However, a formal treaty was signed some years after the fighting stopped. Under the terms of this treaty, Guthrum, now a Christian, had to leave Wessex and go back to East Anglia. So, in 879, the Viking army left Chippenham and went to Cirencester. The official Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum was agreed upon later, perhaps in 879 or 880, when King Ceolwulf II of Mercia was removed from power.

This treaty divided the kingdom of Mercia. The border between Alfred's kingdom and Guthrum's kingdom was set to run along the River Thames, up to the River Lea. It would follow the Lea to its source, then go in a straight line to Bedford, and from Bedford, follow the River Ouse to Watling Street.

This meant Alfred gained control of western Mercia, which was Ceolwulf's kingdom. Guthrum added eastern Mercia to his enlarged kingdom of East Anglia, which became known as the Danelaw. The treaty also gave Alfred control over the Mercian city of London and its mints (where coins were made), at least for a while. The fate of Essex, which West Saxon kings had held since the time of Egbert, is not clear from the treaty. But given Alfred's strong political and military position, it's unlikely he would have given any disputed land to his new godson.

Peace and London's Restoration (880s)

After the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum was signed, around 880, Guthrum's people started settling in East Anglia. This meant Guthrum was no longer a threat. The Viking army, which had spent the winter of 878-879 in Fulham, sailed to Ghent and was active in Europe from 879-892.

Alfred still had to deal with some Danish threats. A year later, in 881, Alfred fought a small sea battle against four Danish ships "on the high seas." Two of the ships were destroyed, and the others surrendered to Alfred's forces. Similar small fights with independent Viking raiders would have happened often during this time, as they had for decades.

In 883, King Alfred received several gifts from Pope Marinus. This was because of Alfred's support and his donations to Rome. One of these gifts was said to be a piece of the true cross, a very valuable item for the religious Saxon king. According to Asser, because Pope Marinus was friends with King Alfred, the pope allowed any Anglo-Saxons living in Rome to be free from taxes.

After signing the treaty with Guthrum, Alfred had a period of peace without major conflicts. Despite this, the king still had to deal with some Danish raids. One of these was a raid in Kent, an allied kingdom, in 885. This was possibly the biggest raid since the battles with Guthrum. Asser's account says the Danish raiders were at the Saxon city of Rochester, where they built a temporary fort to surround the city. Alfred led an Anglo-Saxon army against them. Instead of fighting, the Danes fled to their ships and sailed to another part of Britain. The retreating Danish force supposedly left Britain the following summer.

Not long after the failed Danish raid in Kent, Alfred sent his fleet to East Anglia. The reason for this trip is debated, but Asser says it was for plunder. After sailing up the River Stour, the fleet met 13 or 16 Danish ships (sources differ on the number), and a battle began. The Anglo-Saxon fleet won and, as Huntingdon says, was "laden with spoils." However, the victorious fleet was then caught by surprise when trying to leave the River Stour. A Danish force attacked them at the mouth of the river. The Danish fleet defeated Alfred's fleet, which might have been weakened from the earlier fight.

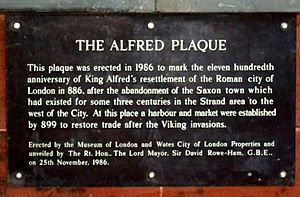

A year later, in 886, Alfred took back the city of London and began to make it livable again. Alfred put his son-in-law, Æthelred, the ealdorman of Mercia, in charge of the city. The rebuilding of London continued through the late 880s. It involved a new street plan, stronger defenses added to the existing Roman walls, and possibly new fortifications on the south bank of the River Thames.

This was also the time when almost all historians agree that the Saxon people of England (before it was fully united) accepted Alfred as their leader. However, Alfred never called himself "King of England."

Between the rebuilding of London and the start of new large-scale Danish attacks in the early 890s, Alfred's reign was quite peaceful. This calm period in the late 880s was marked by the death of Alfred's sister, Æthelswith, in 888 while on her way to Rome. In the same year, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Æthelred, also died. A year later, Guthrum (also known as Athelstan after his baptism), Alfred's former enemy and king of East Anglia, died and was buried in Hadleigh, Suffolk.

Guthrum's death changed the political situation for Alfred. The lack of a strong leader among the Vikings led other warlords to seek power in the following years. Alfred's peaceful years were ending, and war was coming again.

New Viking Attacks Repelled (890s)

After another quiet period, in the autumn of 892 or 893, the Danes attacked again. Their situation in mainland Europe was difficult, so they crossed to England in 330 ships, divided into two groups. They dug in, with the larger group at Appledore, Kent, and the smaller group, led by Hastein, at Milton, also in Kent. The invaders brought their wives and children, showing they planned to conquer and settle. Alfred, in 893 or 894, took a position where he could watch both forces.

While Alfred was talking with Hastein, the Danes at Appledore broke out and headed northwest. Alfred's oldest son, Edward, caught up with them and defeated them in a big battle at Farnham in Surrey. They then took shelter on an island at Thorney, on the River Colne, between Buckinghamshire and Middlesex. There, they were surrounded and forced to give hostages and promise to leave Wessex. They then went to Essex and, after another defeat at Benfleet, joined Hastein's forces at Shoebury.

Alfred had been on his way to help his son at Thorney when he heard that the Northumbrian and East Anglian Danes were surrounding Exeter and another unnamed stronghold on the North Devon coast. Alfred quickly went west and ended the Siege of Exeter. What happened at the other place is not recorded.

Meanwhile, Hastein's force started marching up the Thames Valley, possibly to help their friends in the west. They were met by a large force led by the three powerful leaders (ealdormen) of Mercia, Wiltshire, and Somerset. They were forced to go northwest and were finally caught and surrounded at Buttington. (Some think this is Buttington Tump at the mouth of the River Wye; others think it's Buttington near Welshpool.) An attempt to break through the English lines failed. Those who escaped went back to Shoebury. After getting more fighters, they made a sudden dash across England and took over the ruined Roman walls of Chester. The English did not try to surround them in winter but instead destroyed all the food supplies in the area.

In early 894 or 895, a lack of food forced the Danes to go back to Essex. At the end of the year, the Danes sailed their ships up the River Thames and River Lea. They built defenses twenty miles (32 km) north of London. A direct attack on the Danish lines failed. But later that year, Alfred found a way to block the river, stopping the Danish ships from leaving. The Danes realized they were outsmarted. They headed northwest and spent the winter at Cwatbridge near Bridgnorth. The next year, 896 (or 897), they gave up the fight. Some went back to Northumbria, some to East Anglia. Those who had no connections in England went back to Europe.

Alfred's Military Changes

The Germanic tribes who invaded Britain in the 5th and 6th centuries used unarmored foot soldiers. These soldiers came from their local armies, called the fyrd. The military strength of early Anglo-Saxon England depended on this system. The fyrd was a local militia in each Anglo-Saxon area (shire). All free men had to serve in it. Those who refused military service had to pay fines or lose their land.

According to the law code of King Ine of Wessex, written around 694:

- If a nobleman who owns land doesn't do military service, he must pay 120 shillings and lose his land.

- A nobleman who owns no land must pay 60 shillings.

- A common person must pay a fine of 30 shillings for not doing military service.

Alfred learned from Wessex's past failures before his success in 878. He realized that the old way of fighting gave the Danes an advantage. Both Anglo-Saxons and Danes attacked settlements to get wealth and resources. But they used very different methods. Anglo-Saxons usually attacked head-on, forming a shield wall and moving against the enemy.

In contrast, the Danes preferred to pick easy targets. They planned careful raids to avoid risking all their stolen goods with high-risk attacks. Alfred saw that their plan was to launch smaller attacks from a safe, strong base. They could retreat to this base if they met strong resistance.

These bases were prepared beforehand. Often, they would take over an estate and add defenses like ditches, ramparts, and palisades. Once inside these forts, Alfred realized, the Danes had the upper hand. They could wait out their opponents or crush them with a counter-attack as the attacking forces ran out of food and energy.

The way Anglo-Saxons gathered their forces to defend against raiders also made them weak against the Vikings. It was the job of the local fyrd to deal with local raids. The king could call up the national army to defend the kingdom. But with the Vikings' quick hit-and-run raids, problems with communication and getting supplies meant the national army couldn't gather fast enough. Large areas could be destroyed before the fyrd could assemble and arrive. And even though landowners had to provide men when called, during the attacks in 878, many of them abandoned their king and worked with Guthrum.

With these lessons in mind, Alfred used the peaceful years after his victory at Edington to rebuild his kingdom's military defenses. During a trip to Rome, Alfred had stayed with Charles the Bald. It's possible he learned how the Carolingian kings dealt with the Viking problem. Learning from their experiences, he created a system of taxes and defense for his own kingdom. Also, there had been a system of forts in Mercia before the Vikings, which might have influenced him. So, when the Viking raids started again in 892, Alfred was better prepared. He had a standing, mobile army, a network of garrisons (military bases), and a small fleet of ships for rivers and estuaries.

Managing the Army and Taxes

Landowners in Anglo-Saxon England had three main duties based on their land: military service, building forts, and repairing bridges. This was called trinoda neccessitas or trimoda neccessitas. The Old English name for the fine for not doing military service was fierdwite or fyrdwitee.

To keep the burhs (fortified towns) running and to make the fyrd a standing army, Alfred expanded the tax and conscription system. This system was based on how much land a tenant owned. The "hide" was the basic unit for assessing a tenant's public duties. A hide was thought to be enough land to support one family. The size of a hide would change based on the land's value and resources. A landowner had to provide service based on how many hides they owned.

The Burghal System

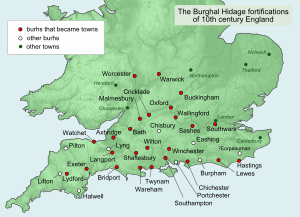

Alfred's new military defense system was built around a network of burhs, which were fortified towns. These were placed at important points across the kingdom. There were 33 burhs in total, about 30 km (19 miles) apart. This allowed the army to respond to attacks anywhere in the kingdom within a single day.

Alfred's burhs (later called boroughs) included old Roman towns like Winchester. In these, the stone walls were repaired, and ditches were added. Other burhs were massive earthen walls surrounded by wide ditches, likely strengthened with wood and fences, like at Burpham, Sussex. The size of the burhs varied from tiny outposts like Pilton to large forts in established towns, with Winchester being the biggest.

A document from that time, called the Burghal Hidage, explains how the system worked. It lists the "hidage" for each fortified town. For example, Wallingford had a hidage of 2400. This meant that the landowners there had to provide and feed 2,400 men. This was enough men to maintain 9,900 feet (3 km) of wall. In total, 27,071 soldiers were needed across the whole system. This was about one in four of all free men in Wessex.

Many burhs were "twin towns" that sat on both sides of a river and were connected by a fortified bridge. These double-burhs blocked river passage, forcing Viking ships to go under a guarded bridge. Men on the bridge could attack with stones, spears, or arrows. Other burhs were near fortified royal homes, giving the king better control over his strongholds.

The burhs were also connected by a road system used by the army, known as herepaths. These roads allowed an army to gather quickly, sometimes from more than one burh, to fight Viking invaders. This network made it much harder and more dangerous for Viking raiders, especially those carrying stolen goods. The Vikings didn't have the right equipment to besiege a burh. They also weren't used to long sieges, preferring quick attacks and easy retreats to their strong forts. Their only option was to try to starve a burh into surrendering. But this gave the king time to send his mobile army or soldiers from nearby burhs along the well-kept army roads. In such cases, the Vikings were very vulnerable to being chased by the king's combined forces. Alfred's burh system was so strong that when the Vikings returned in 892 and successfully attacked a half-finished, poorly guarded fort in Kent, the Anglo-Saxons were able to keep them from going deep into Wessex and Mercia.

Alfred's burghal system was a new and clever military idea, but it was likely very expensive. His biographer Asser wrote that many nobles complained about the new demands placed on them, even though they were for "the common needs of the kingdom."

Alfred also tried his hand at designing ships. In 896, he ordered a small fleet to be built. These were perhaps a dozen or so longships, and at 60 oars, they were twice the size of Viking warships. This was not the very first time England had a navy, as some Victorians claimed. Wessex already had a royal fleet before this. King Athelstan of Kent and Ealdorman Ealhhere had defeated a Viking fleet in 851, capturing nine ships. Alfred himself had also led naval actions in 882.

However, the writer of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and probably Alfred himself saw 897 as a big step forward for Wessex's naval power. The chronicler praised Alfred by saying his ships were not only bigger but also faster, more stable, and sat higher in the water than Danish or Frisian ships. It's likely that Alfred, with help from Asser who knew about classical history, used designs from Greek and Roman warships. These ships had high sides and were built for fighting, not just for sailing.

Alfred wanted to control the sea. If he could stop raiding fleets before they landed, he could prevent his kingdom from being destroyed. Alfred's ships might have been good in theory. But in practice, they were too big to move well in the narrow waters of estuaries and rivers, which were the only places where naval battles could happen.

Warships at that time were not designed to sink other ships but to carry soldiers. It's thought that, like sea battles in later Viking Age Scandinavia, these battles involved one ship pulling alongside an enemy vessel. Then, the crew would tie the two ships together before boarding the enemy ship. The result was basically a land battle with hand-to-hand fighting on the two tied-together ships.

In the one recorded naval battle in 896, Alfred's new fleet of nine ships stopped six Viking ships at the mouth of an unknown river in southern England. The Danes had beached half their ships and gone inland, either to rest or to find food. Alfred's ships immediately moved to block their escape to the sea. The three Viking ships still afloat tried to break through the English lines. Only one made it. Alfred's ships stopped the other two.

The English crew tied the Viking boats to their own, boarded the enemy ships, and killed everyone on board. The one ship that escaped did so only because all of Alfred's heavy ships got stuck when the tide went out. What followed was a land battle between the crews of the grounded ships. The Danes, greatly outnumbered, would have been wiped out if the tide hadn't risen. When it did, the Danes rushed back to their boats. Their boats were lighter and had shallower bottoms, so they floated free before Alfred's ships. The English watched helplessly as the Vikings rowed past them. The pirates had suffered so many deaths (120 Danes dead against 62 Frisians and English) that they had trouble getting out to sea. All were too damaged to row around Sussex, and two were driven against the Sussex coast (possibly at Selsey Bill). The shipwrecked sailors were brought before Alfred at Winchester and hanged.

Alfred's Legal Reforms

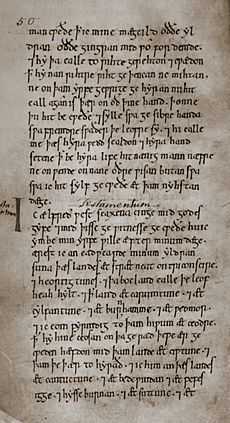

In the late 880s or early 890s, Alfred released a long law code called a domboc. It included his "own" laws and a code from King Ine of Wessex, who ruled in the late 7th century. These laws were organized into 120 chapters. In his introduction, Alfred explained that he collected laws from many old "synod-books." He wrote down "many of the ones that our forefathers observed—those that pleased me; and many of the ones that did not please me, I rejected with the advice of my councillors, and commanded them to be observed in a different way."

Alfred specifically mentioned laws he found from the time of Ine, his relative, or Offa, king of the Mercians, or King Æthelberht of Kent. Æthelberht was the first among the English people to be baptized. Alfred added Ine's laws to his code rather than fully combining them. Although he included a list of payments for injuries to different body parts, like Æthelbert had, the two lists of payments don't match up. Offa is not known to have issued a law code. Historian Patrick Wormald thinks Alfred might have been thinking of the church laws from 786 that were given to Offa by two papal representatives.

About one-fifth of the law code is Alfred's introduction. This includes English translations of the Ten Commandments, some parts from the Book of Exodus, and the "Apostolic Letter" from Acts of the Apostles (15:23–29). The Introduction can be seen as Alfred's thoughts on the meaning of Christian law. It connects God's gift of law to Moses with Alfred's own laws for the West Saxon people. By doing this, it linked the holy past to his own time and presented Alfred's law-giving as a kind of divine law.

Alfred divided his code into 120 chapters. This was because 120 was the age Moses died. In the number symbolism of early medieval Bible scholars, 120 stood for law. The connection between Mosaic Law and Alfred's code is the "Apostolic Letter." This letter explained that Christ "had come not to shatter or annul the commandments but to fulfill them; and he taught mercy and meekness" (Intro, 49.1). The mercy that Christ brought into Mosaic Law is behind the injury payments found in old law codes. Christian councils "established, through that mercy which Christ taught, that for almost every misdeed at the first offence secular lords might with their permission receive without sin the monetary compensation, which they then fixed."

The only crime that could not be paid for with money was betraying one's lord. This was because "Almighty God judged none for those who despised Him, nor did Christ, the Son of God, judge any for the one who betrayed Him to death; and He commanded everyone to love his lord as Himself." Alfred changed Christ's command from "Love your neighbour as yourself" (Matt. 22:39–40) to loving your earthly lord as you would love Christ himself. This shows how important Alfred thought loyalty to a lord was. He saw it as a sacred bond given by God to govern people.

When you look at the laws themselves, after the introduction, it's hard to find a clear order. It seems like a mix of different laws. The law code, as it has been kept, is not very useful for actual lawsuits. In fact, some of Alfred's laws went against Ine's laws, which were part of the code. Historian Patrick Wormald explains that Alfred's law code should be seen not as a legal handbook, but as a statement about kingship. It was "designed more for symbolic impact than for practical direction." In practical terms, the most important law in the code might have been the very first: "We enjoin, what is most necessary, that each man keep carefully his oath and his pledge." This shows a basic rule of Anglo-Saxon law.

Alfred paid a lot of attention to legal matters. Asser highlights Alfred's concern for fair judgments. According to Asser, Alfred insisted on reviewing disputed decisions made by his officials. He "would carefully look into nearly all the judgements which were passed [issued] in his absence anywhere in the realm, to see whether they were just or unjust." A document from his son Edward the Elder's reign shows Alfred hearing one such appeal in his room while washing his hands.

Asser describes Alfred as a Solomonic judge. He was very careful in his own legal investigations and critical of royal officials who made unfair or unwise judgments. Although Asser never mentions Alfred's law code, he does say that Alfred insisted his judges be able to read. This was so they could "apply themselves to the pursuit of wisdom." Not following this royal order would lead to losing their job.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, started during Alfred's time, was probably written to help unite England. Asser's The Life of King Alfred highlighted Alfred's achievements and good qualities. It's possible the document was designed this way so it could be shared in Wales, as Alfred had recently gained control over that country.

Alfred's Foreign Relations

Asser speaks grandly about Alfred's dealings with other countries, but we don't have much clear information. Alfred's interest in foreign lands is shown by the notes he added to his translation of Orosius. He wrote to Elias III, the Patriarch of Jerusalem. Also, messengers were often sent to Rome to deliver English donations to the Pope. Around 890, Wulfstan of Hedeby traveled from Hedeby in Jutland along the Baltic Sea to the Prussian trading town of Truso. Alfred personally gathered details about this trip.

Alfred's relationships with the Celtic princes in western Britain are clearer. Asser says that fairly early in Alfred's reign, the princes of South Wales asked for Alfred's protection. This was because they were under pressure from North Wales and Mercia. Later in his reign, the North Welsh followed their example. They worked with the English in the campaign of 893 (or 894). We can trust Asser's word that Alfred sent donations to Irish and European monasteries. The visit of three pilgrim "Scots" (meaning Irish) to Alfred in 891 is definitely true. The story that Alfred himself was sent to Ireland as a child to be healed by Saint Modwenna, though a myth, might show Alfred's interest in that island.

Alfred's Focus on Religion and Culture

In the 880s, while Alfred was pushing his nobles to build and staff the burhs, he also started a big effort to bring back learning. He might have been inspired by Charlemagne almost a century earlier. During this time, the Viking raids were often seen as a punishment from God. Alfred might have wanted to bring back strong religious belief to calm God's anger.

This effort involved bringing in educated churchmen from Mercia, Wales, and other countries. They helped improve the quality of the court and the bishops. Alfred also set up a court school to teach his own children, the sons of his nobles, and smart boys from less important families. He tried to make sure that people in positions of power could read and write. He also had many important Latin books translated into English, which he thought "all men needed to know." He also had a chronicle put together that told the story of his kingdom and family. This chronicle included a family tree that went all the way back to Adam, giving the West Saxon kings a biblical history.

We don't know much about the church under Alfred. The Danish attacks had badly damaged monasteries. Although Alfred founded new monasteries at Athelney and Shaftesbury, these were the first new ones in Wessex since the early 8th century. According to Asser, Alfred had to invite foreign monks to England for his monastery at Athelney because local people weren't very interested in becoming monks.

Alfred didn't make big, systematic changes to church institutions or religious practices in Wessex. For him, the most important thing for the kingdom's spiritual rebirth was to appoint bishops and abbots who were religious, learned, and trustworthy. As king, he believed he was responsible for both the worldly and spiritual well-being of his people. For Alfred, worldly and spiritual power were not separate.

He was comfortable giving his translation of Gregory the Great's Pastoral Care to his bishops. This helped them better train and supervise priests. He also used these same bishops as royal officials and judges. His strong faith didn't stop him from taking church lands that were in important locations, especially along the border with the Danelaw. He gave these lands to royal officials who could better defend them against Viking attacks.

How Danish Raids Affected Education

The Danish raids had a terrible impact on learning in England. Alfred wrote in the introduction to his translation of Gregory's Pastoral Care that "learning had declined so thoroughly in England that there were very few men on this side of the Humber who could understand their divine services in English, or even translate a single letter from Latin into English: and I suppose that there were not many beyond the Humber either." Alfred probably made this sound worse for dramatic effect. Latin learning hadn't completely disappeared, as shown by the learned churchmen like Plegmund, Wæferth, and Wulfsige at his court.

The making of manuscripts in England dropped sharply around the 860s when the Viking invasions truly began. It didn't pick up again until the end of the century. Many Anglo-Saxon manuscripts burned along with the churches that held them. A formal document from Christ Church, Canterbury, dated 873, is so badly made and written that historian Nicholas Brooks suggested the scribe was either so blind he couldn't read what he wrote or knew little to no Latin. Brooks concluded, "It is clear that the metropolitan church [of Canterbury] must have been quite unable to provide any effective training in the scriptures or in Christian worship."

Starting a Court School

Alfred started a court school to educate his own children, the children of nobles, and "a good many of lesser birth." There, they studied books in both English and Latin. They "devoted themselves to writing, to such an extent... they were seen to be devoted and intelligent students of the liberal arts." He brought scholars from Europe and Britain to help bring back Christian learning in Wessex and to teach him personally. Grimbald and John the Saxon came from Francia. Plegmund (whom Alfred made archbishop of Canterbury in 890), Bishop Wærferth of Worcester, Æthelstan, and the royal chaplains Werwulf came from Mercia. Asser came from St David's in southwestern Wales.

Promoting Education in English

Alfred's goals for education went beyond just starting a court school. He believed that without Christian wisdom, there could be no success or prosperity in war. So, Alfred wanted "to set to learning (as long as they are not useful for some other employment) all the free-born young men now in England who have the means to apply themselves to it." He knew that Latin literacy was declining in his kingdom. Alfred suggested that basic education should be taught in English. Those who wanted to become priests would then continue their studies in Latin.

There were few "books of wisdom" written in English. Alfred tried to fix this with a big project at his court. He had books he thought "most necessary for all men to know" translated into English. We don't know when Alfred started this project, but it might have been in the 880s when Wessex had a break from Viking attacks. Until recently, Alfred was often thought to have written many of these translations himself. But now, scholars doubt this in almost all cases. They often call them "Alfredian" translations, meaning Alfred likely supported them, but probably didn't write them himself.

Besides the lost Handboc or Encheiridion (which seems to have been a notebook the king kept), the first work translated was the Dialogues of Gregory the Great. This book was very popular in the Middle Ages. The translation was done by Wærferth, Bishop of Worcester, at Alfred's command. The king only wrote an introduction. Amazingly, Alfred himself, with advice from his court scholars, translated four works: Gregory the Great's Pastoral Care, Boethius's Consolation of Philosophy, St. Augustine's Soliloquies, and the first fifty psalms of the Psalter.

We could also add the translation of parts of the Vulgate Book of Exodus found in Alfred's law code. Scholars no longer believe that the Old English versions of Orosius's Histories against the Pagans and Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People were translated by Alfred himself. This is because of differences in words and writing style. However, it's still generally agreed that they were part of Alfred's translation project. Simon Keynes and Michael Lapidge also suggest this for Bald's Leechbook and the anonymous Old English Martyrology.

The introduction to Alfred's translation of Pope Gregory the Great's Pastoral Care explained why he thought it was important to translate such works from Latin into English. This introduction might actually be Alfred's own writing. Although he said his method was to translate "sometimes word for word, sometimes sense for sense," the translation is actually very close to the original. However, through his choice of words, he often blurred the line between spiritual and worldly power. Alfred intended the translation to be used and sent copies to all his bishops. People were so interested in Alfred's translation of Pastoral Care that copies were still being made in the 11th century.

Boethius's Consolation of Philosophy was the most popular philosophy book of the Middle Ages. Unlike the translation of the Pastoral Care, the Alfredian text changes the original quite a bit. Even though Dr. G. Schepss showed that many additions came from notes and comments the translator used, there is still much in the work that is unique to this translation. It is thought to show Alfred's ideas about kingship. In this Boethius translation, the famous sentence appears: "To speak briefly: I desired to live worthily as long as I lived, and after my life to leave to them that should come after, my memory in good works." Only two copies of this book have survived. In one, the writing is prose (like regular sentences), and in the other, it's a mix of prose and alliterating verse (poetry with repeating sounds). The second copy was badly damaged in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The last of Alfred's works is called Blostman ('Blooms') or Anthology. The first half is mostly based on the Soliloquies of St Augustine of Hippo. The rest comes from different sources. People have traditionally thought that much of this work contains Alfred's own thoughts and is very typical of him. The last words of it are often quoted and make a fitting tribute to this great English king: "Therefore, he seems to me a very foolish man, and truly wretched, who will not increase his understanding while he is in the world, and ever wish and long to reach that endless life where all shall be made clear." Alfred appears as a character in the 12th or 13th-century poem The Owl and the Nightingale, where his wisdom and skill with proverbs are praised. The Proverbs of Alfred, a 13th-century work, contains sayings that probably didn't come from Alfred but show his lasting reputation for wisdom in the Middle Ages.

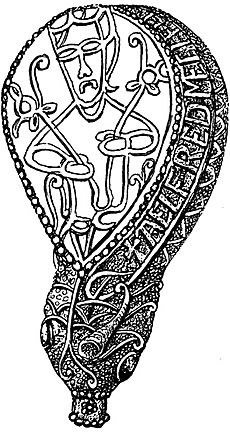

The Alfred jewel, found in Somerset in 1693, has long been connected to King Alfred. This is because of its Old English writing: "AELFRED MEC HEHT GEWYRCAN" ('Alfred ordered me to be made'). The jewel is about 2.5 inches (6.4 cm) long. It's made of filigreed gold, with a highly polished quartz crystal. Underneath the crystal is a colorful enamel picture of a man holding flowery scepters. This might represent Sight or the Wisdom of God.

It was once attached to a thin rod or stick, based on the hollow socket at its base. The jewel definitely dates from Alfred's reign. We don't know its exact purpose, but it's often suggested that the jewel was one of the æstels—pointers used for reading. Alfred ordered these to be sent to every bishopric along with a copy of his translation of the Pastoral Care. Each æstel was worth the large sum of 50 mancuses, which matches the high quality and expensive materials of the Alfred jewel.

Historian Richard Abels believes Alfred's educational and military changes worked together. Abels argues that for Alfred, bringing back religion and learning in Wessex was just as important for defending his kingdom as building the burhs. As Alfred noted in the introduction to his English translation of Gregory the Great's Pastoral Care, kings who don't follow their divine duty to promote learning can expect their people to suffer earthly punishments. He told his readers of the Boethius translation that seeking wisdom was the surest way to power: "Study wisdom, then, and, when you have learned it, condemn it not, for I tell you that by its means you may without fail attain to power, yea, even though not desiring it."

The way Asser and the chronicler described the West Saxon resistance to the Vikings as a Christian holy war was more than just words or 'propaganda'. It showed Alfred's own belief that God rewarded good actions and punished bad ones. He saw a Christian world where God was the Lord, kings owed obedience to God, and through God, they got their power over their followers. To convince his nobles to work for the 'common good', Alfred and his court scholars made the idea of Christian kingship stronger. They built on the ideas of earlier kings like Offa, and church writers like Bede, Alcuin, and others from the Carolingian renaissance. This wasn't a trick to make his subjects obey. It was a core part of Alfred's view of the world. He believed, like other kings in 9th-century England and Francia, that God had given him responsibility for both the spiritual and physical well-being of his people. If the Christian faith fell apart in his kingdom, if the clergy were too uneducated to understand the Latin words they used in services, if old monasteries and churches were empty because people didn't care, he would be answerable to God, just as Josiah had been. Alfred's main responsibility was to care for his people's spiritual well-being.

Alfred's Appearance and Personality

Asser wrote about Alfred in his Life of King Alfred: "Now, he was greatly loved, more than all his brothers, by his father and mother—indeed, by everybody—with a universal and profound love, and he was always brought up in the royal court and nowhere else. ... [He] was seen to be more comely in appearance than his other brothers, and more pleasing in manner, speech and behaviour ... [and] in spite of all the demands of the present life, it has been the desire for wisdom, more than anything else, together with the nobility of his birth, which have characterized the nature of his noble mind."

Asser also wrote that Alfred didn't learn to read until he was 12 years old or even later. This was described as "shameful negligence" by his parents and teachers. However, Alfred was an excellent listener and had an amazing memory. He remembered poetry and psalms very well. A story is told by Asser about how his mother held up a book of Saxon poetry to him and his brothers. She said, "I shall give this book to whichever one of you can learn it the fastest." Alfred excitedly asked, "Will you really give this book to the one of us who can understand it the soonest and recite it to you?" He then took it to his teacher, learned it, and recited it back to his mother.

Alfred is also known for carrying a small book, probably like a medieval pocket notebook. It contained psalms and many prayers that he often collected. Asser wrote: "[these] he collected in a single book, as I have seen for myself; amid all the affairs of the present life he took it around with him everywhere for the sake of prayer, and was inseparable from it."

Alfred was an excellent hunter in every type of hunting sport. He was remembered as an enthusiastic huntsman whose skills no one could match.

Even though he was the youngest of his brothers, he was probably the most open-minded. He was an early supporter of education. His desire for learning might have come from his early love of English poetry and his inability to read or write it down until later in life. Asser wrote that "[Alfred] could not satisfy his craving for what he desired the most, namely the liberal arts; for, as he used to say, there were no good scholars in the entire kingdom of the West Saxons at that time."

Alfred's Family Life

In 868, Alfred married Ealhswith, who was the daughter of a Mercian nobleman named Æthelred Mucil, the Ealdorman of the Gaini. The Gaini were likely one of the tribal groups within Mercia. Ealhswith's mother, Eadburh, was part of the Mercian royal family.

Alfred and Ealhswith had five or six children together. These included Edward the Elder, who became king after his father, and Æthelflæd, who became the Lady (ruler) of the Mercians in her own right. Their daughter Ælfthryth married Baldwin II, the Count of Flanders. Alfred's mother was Osburga, daughter of Oslac of the Isle of Wight, who was the Chief Butler of England. Asser, in his Vita Ælfredi, claims this shows Alfred's family line came from the Jutes of the Isle of Wight. This is unlikely because Bede tells us that the Saxons under Cædwalla killed all of them. In 2008, the skeleton of Queen Eadgyth, Alfred the Great's granddaughter, was found in Magdeburg Cathedral in Germany. In 2010, it was confirmed that these remains belonged to her, making her one of the earliest members of the English royal family found.

Osferth was mentioned as a relative in King Alfred's will. He signed official documents in a high position until 934. A document from King Edward's reign mistakenly called him the king's brother, according to Keynes and Lapidge. However, Janet Nelson believes he was probably an illegitimate son of King Alfred.

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Æthelflæd | 12 June 918 | Married around 886 to Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians (died 911); they had children. | |

| Edward | about 874 | 17 July 924 | Married (1) Ecgwynn, (2) Ælfflæd, (3) in 919 Eadgifu. |

| Æthelgifu | Abbess of Shaftesbury. | ||

| Æthelweard | 16 October 922(?) | Married and had children. | |

| Ælfthryth | 929 | Married Baldwin II (died 918); they had children. |

Alfred's Death and Burial

Alfred died on October 26, 899. We don't know exactly how he died, but he suffered throughout his life from a painful and unpleasant illness. His biographer Asser gave a detailed description of Alfred's symptoms. This has allowed modern doctors to suggest possible diagnoses. It's thought he might have had either Crohn's disease or haemorrhoidal disease. His grandson, King Eadred, seems to have suffered from a similar illness.

Alfred was first buried temporarily in the Old Minster in Winchester. Then, four years after his death, he was moved to the New Minster (which might have been built just for him). When the New Minster moved to Hyde, just north of the city, in 1110, the monks moved to Hyde Abbey. Alfred's body, along with those of his wife and children, were also moved there and likely buried in front of the main altar. Soon after the abbey was closed in 1539, during the reign of Henry VIII, the church was torn down, but the graves were left untouched.

The royal graves and many others were probably found by accident in 1788. This was when a prison was being built by convicts on the site. Prisoners dug across the altar area to get rid of rubble left from the abbey's demolition. Coffins were stripped of their lead, and bones were scattered and lost. The prison was torn down between 1846 and 1850. More digs in 1866 and 1897 didn't find clear answers. In 1866, an amateur historian named John Mellor claimed to have found some bones from the site that he said belonged to Alfred. These bones later ended up with the vicar of nearby St Bartholomew's Church, who reburied them in an unmarked grave in the church graveyard.

Excavations by the Winchester Museums Service at the Hyde Abbey site in 1999 found a second pit dug in front of where the high altar would have been. This pit was likely from Mellor's 1886 excavation. The 1999 archaeological dig uncovered the foundations of the abbey buildings and some bones. Bones thought at the time to be Alfred's turned out to belong to an elderly woman instead.

In March 2013, the Diocese of Winchester dug up the bones from the unmarked grave at St Bartholomew's and put them in safe storage. The diocese didn't claim they were Alfred's bones. They just wanted to secure them for later study and protect them from people who might be interested after the recent discovery of King Richard III's remains. The bones were radiocarbon-dated, but the results showed they were from the 1300s, so they were not Alfred's. In January 2014, a piece of pelvis found in the 1999 excavation of the Hyde site, which had been in a Winchester museum storage room, was radiocarbon-dated to the correct time period. It has been suggested that this bone might belong to either Alfred or his son Edward, but this is still not proven.

Alfred's Lasting Legacy

Alfred is honored as a saint by some Christian groups. However, an attempt by Henry VI of England in 1441 to have him officially recognized as a saint by the pope was not successful. The Anglican Communion honors him as a Christian hero. His feast day or commemoration is on October 26. You can often see him in stained glass windows in Church of England parish churches.

Alfred asked Bishop Asser to write his biography. This book naturally highlighted Alfred's good qualities. Later medieval historians, like Geoffrey of Monmouth, also helped build Alfred's positive image. By the time of the Reformation, Alfred was seen as a very religious Christian ruler. He promoted the use of English instead of Latin, so his translated works were seen as pure and not influenced by later Roman Catholic ideas from the Normans. Because of this, it was writers in the 16th century who first called Alfred "the Great," not his own friends or people from his time. This title was kept by later generations of politicians and empire-builders. They saw Alfred's love for his country, his success against invaders, his support for education, and his creation of fair laws as supporting their own beliefs.

Many schools and universities are named in Alfred's honor. These include:

- The University of Winchester was created from the former 'King Alfred's College, Winchester' (1928 to 2004).

- Alfred University and Alfred State College in Alfred, New York, are both named after the king. The local phone exchange for Alfred University is 871, remembering the year Alfred became king.

- In honor of Alfred, the University of Liverpool created a King Alfred Chair of English Literature.

- King Alfred's Academy, a secondary school in Wantage, Oxfordshire, which is Alfred's birthplace.

- King's Lodge School in Chippenham, Wiltshire, is named because King Alfred's hunting lodge is said to have been on or near the school's site.

- The King Alfred School & Specialist Sports Academy, Burnham Road, Highbridge, is named due to its closeness to Brent Knoll (a beacon site) and Athelney.

- The King Alfred School in Barnet, North London, UK.

- King Alfred's Middle School, Shaftesbury, Dorset (now closed after changes).

- King's College, Taunton, Somerset. (The king referred to is King Alfred).

- King Alfred's house in Bishop Stopford's School at Enfield.

- Saxonwold Primary School in Gauteng, South Africa, names one of its houses after King Alfred. The others are Bede, Caedmon, and Dunston.

The Royal Navy has named one ship and two shore establishments HMS King Alfred. One of the first ships of the US Navy was named USS Alfred in his honor. In 2002, Alfred was ranked number 14 in the BBC's list of the 100 Greatest Britons after a vote across the UK.

Statues Honoring Alfred

Pewsey Statue

A large statue of King Alfred the Great stands in the middle of Pewsey. It was revealed in June 1913 to celebrate the coronation of King George V.

Wantage Statue

A statue of Alfred the Great, located in the Wantage market place, was sculpted by Count Gleichen, a relative of Queen Victoria. It was unveiled on July 14, 1877, by the Prince and Princess of Wales. The statue was damaged on New Year's Eve 2007, losing part of its right arm and axe. After the arm and axe were replaced, the statue was again damaged on Christmas Eve 2008, losing its axe.

Winchester Statue

A bronze statue of Alfred the Great stands at the eastern end of The Broadway, near where Winchester's medieval East Gate used to be. The statue was designed by Hamo Thornycroft and put up in 1899 to mark one thousand years since Alfred's death. The statue stands on a base made of two huge blocks of gray Cornish granite.

Images for kids

-

Alfred's father Æthelwulf of Wessex in the early 14th-century Genealogical Roll of the Kings of England

-

King Alfred's Tower (1772) on the supposed site of Egbert's Stone, the mustering place before the Battle of Edington.

-

The walled defense around a burh. The City Walls of Alfred's capital, Winchester. Saxon and medieval work on Roman foundations.

-

A posthumous image of Queen Ealhswith, 1220

-

Eighteenth-century portrait of Alfred by Samuel Woodforde

-

1913 statue of Alfred in Pewsey, Wiltshire

See also

In Spanish: Alfredo el Grande para niños

In Spanish: Alfredo el Grande para niños