Eastern philosophy facts for kids

Eastern philosophy or Asian philosophy is about the many ways of thinking that started in East Asia and South Asia. This includes ideas from China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, which are big in East Asia. It also covers Indian philosophy (like Hindu philosophy, Jain philosophy, and Buddhist philosophy), which is important in India, Southeast Asia, Tibet, and Mongolia.

Contents

- Indian philosophy: Ancient wisdom

- East Asian philosophies: Ancient wisdom and new ideas

- Eastern and Western philosophy: Blending ideas

- Thinking about "Eastern philosophy"

- See also

Indian philosophy: Ancient wisdom

Indian philosophy comes from ancient ways of thinking in the Indian subcontinent. Some ideas, like those in Jainism, might be as old as the Indus Valley civilization. Many major Hindu schools of thought grew between the start of the Common Era and the Gupta Empire. These schools mixed traditional ideas with new ones from Buddhism and Jainism. Hindu thought also spread to places like the Srivijaya empire in Indonesia and the Khmer Empire in Cambodia.

Today, these ideas are often called Hinduism. Hinduism is a main way of life in South Asia. It includes many different groups like Shaivism and Vaishnavism. It also teaches about daily rules based on karma (actions and their results) and dharma (doing what is right). Hinduism is not one strict set of beliefs but many different ways of thinking. It is the world's third-largest religion and is sometimes called the "oldest religion" because its roots go back so far.

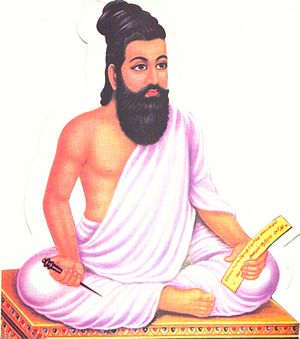

Some of the oldest writings about Indian philosophy are the Upanishads, from around 1000–500 BCE. Important ideas include dharma, karma, samsara (the cycle of rebirth), moksha (freedom from this cycle), and ahimsa (non-violence). Indian thinkers also studied how we know things (called epistemology) and logic. They looked into big questions about reality, the soul, and what is true. Texts like the Arthashastra (around 4th century BCE) even discussed political ideas. The Tirukkural, written by the Tamil poet Valluvar, also shares ideas from Jain and Hindu philosophies.

Later, new ideas like Tantra appeared. Buddhism mostly left India after the Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent, but it stayed strong in the Himalayan areas and South India. In more recent times, new schools of thought like Navya-Nyāya (the 'new reason') became popular.

Orthodox and heterodox schools of thought

Indian philosophy groups its schools into two main types: orthodox (āstika) and heterodox (nāstika). This grouping depends on whether they believe the Vedas (ancient sacred texts) are a true source of knowledge. It can also depend on whether they believe in Brahman (the ultimate reality) and Atman (the individual soul), or in an afterlife and gods.

There are six main orthodox schools of Hindu philosophy: Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Samkhya, Yoga, Mīmāṃsā, and Vedanta. There are also five main heterodox schools: Jainism, Buddhism, Ajivika, Ajñana, and Cārvāka. Each Hindu school has many writings about how we gain knowledge.

Over time, some of these schools changed or combined. For example, Vedanta became very important in later Hinduism.

Sāmkhya and Yoga: Mind and body

Samkhya is a philosophy that sees the world as having two main parts: consciousness and matter. It's based on texts from around 320–540 CE. The Yoga school is very similar. It focuses on meditation and finding freedom. Its main text is the Yoga Sutras (around 400 CE). Early ideas like Samkhya can be found in the ancient Upanishads.

A key difference is that Yoga allows for the idea of a God, while most Samkhya thinkers did not. Samkhya believes we can gain knowledge through perception, inference, and the words of trusted sources. It has a complex idea about how consciousness and matter developed.

Nyāya: The path to correct knowledge

The Nyaya school focuses on how we get knowledge. It is based on the Nyāya Sūtras (from around 6th century BCE to 2nd century CE). Nyāya believes that human suffering comes from not knowing the truth. To be free, we need correct knowledge. So, they studied how to find true knowledge.

Nyāya accepts four ways to gain knowledge: perception, inference, comparison, and the words of reliable experts. Nyāya also believes in a form of realism, meaning that things exist independently of our minds.

The Nyāya Sūtras was a very important text. It set the stage for many debates between different Indian philosophical schools. It even argued against the idea of a creator God, which became a big topic in medieval Hinduism.

Vaiśeṣika: Understanding atoms

Vaisheshika is a school that believes the universe is made of tiny, indestructible parts called atoms. It only accepts two ways of knowing: perception and inference. This philosophy thought that everything we experience is a mix of these atoms.

Vaiśeṣika grouped everything we experience into six categories: substance, quality, activity, generality, particularity, and inherence. Later thinkers added a seventh category: non-existence. The first three categories are things we can perceive and truly exist. The others are ways our minds organize things.

Mīmāṃsā: Ritual and language

Mīmāṃsā is a school focused on religious rituals and understanding the Vedas. For them, studying dharma (ritual and social duty) was most important. They believed the Vedas were "eternal, had no author, and were always right." They thought that the commands and chants in the Vedas were the most important actions.

Because they focused on texts, Mīmāṃsā also developed ideas about philology (the study of language in historical sources) and the philosophy of language. They believed language's main purpose was to tell people how to act correctly and perform rituals. Mīmāṃsā thinkers were mostly atheistic. They felt there wasn't enough proof for God's existence and that the gods in the Vedas were just names or powers, not real beings outside of the rituals.

A key text is the Mīmāṃsā Sūtra by Jaimini. Important scholars include Prabhākara and Kumārila Bhaṭṭa. Mīmāṃsā greatly influenced Vedanta, which is also called Uttara-Mīmāṃsā. However, Mīmāṃsā focused on rituals, while Vedānta focused on gaining knowledge from the later parts of the Vedas, like the Upanishads.

Vedānta: The end of the Vedas

Vedānta means "end of the Vedas". It is a group of traditions that look at philosophical questions found in three main texts: the Principal Upanishads, the Brahma Sutras, and the Bhagavad Gita. Vedānta sees the Vedas, especially the Upanishads, as a reliable source of knowledge.

These schools mainly focus on the nature of and the relationship between Brahman (the ultimate reality, universal consciousness), Ātman (the individual soul), and Prakriti (the world we experience).

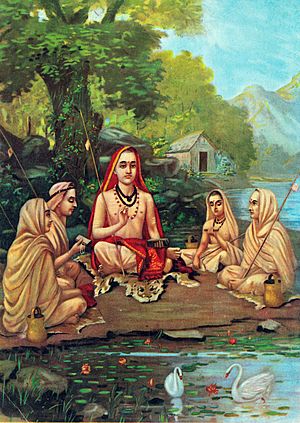

Different types of Vedānta include Advaita (non-dualism, meaning everything is one), Vishishtadvaita (qualified non-dualism), and Dvaita (dualism, meaning two separate realities). Because of the popularity of the bhakti movement (devotion to a god), Vedānta became the most important type of Hinduism after the medieval period.

Heterodox or Śramaṇic schools: Different paths

The heterodox schools are linked to the non-Vedic Śramaṇa traditions. These traditions existed in India even before the 6th century BCE. The Śramaṇa movement led to many different ideas. Some accepted or rejected the idea of a soul, atoms, materialism, atheism, or fatalism. They also explored free will, extreme self-control, strict non-violence, and vegetarianism. Important philosophies from this movement include Jainism, early Buddhism, Cārvāka, Ajñana, and Ājīvika.

Jain philosophy: Non-violence and truth

Jain philosophy looks deeply into questions about metaphysics (the nature of reality), the universe, and how we know things. Jainism is an ancient Indian religion that believes in many gods but not a single creator God. It continues the old Śramaṇa tradition, which existed alongside the Vedic tradition.

Key ideas in Jain philosophy include:

- The idea that mind and body are separate.

- No belief in a creator God.

- The concept of karma.

- Belief in an eternal universe that was not created.

- Strong emphasis on non-violence.

- The idea that truth has many sides.

- Morality focused on freeing the soul.

Jainism tries to explain why things exist, what the universe is like, and how to achieve freedom. It often stresses self-control and giving up worldly things. It also promotes the idea that truth can be seen from many different viewpoints. Jainism strongly believes that each person is responsible for their own choices and that self-effort leads to freedom.

Jain thinkers have greatly helped Indian philosophy. Ideas like Ahimsa, Karma, Moksa, and Samsara are shared with other Indian religions like Hinduism and Buddhism. Jain philosophy comes from the teachings of Mahavira and other Tirthankaras. Many Jain philosophers, from ancient times to more recent ones, have added unique Jain ideas to Indian thought.

Cārvāka: The materialist view

Cārvāka (also called Lokāyata) was an atheistic philosophy that believed in materialism. This means they thought only physical matter exists. They were skeptical and rejected the Vedas and all supernatural ideas. Cārvāka thinkers were very critical of other philosophies. They said the Vedas were full of lies and contradictions, made up by humans just to give priests a job.

They also criticized Buddhists and Jains, making fun of ideas like freedom, reincarnation, and gaining good or bad karma. They thought giving up pleasure to avoid pain was foolish. Cārvāka believed that perception was the main way to get knowledge, and they didn't trust inference (drawing conclusions). The main texts of Cārvāka are lost today.

Ājīvika: All is fate

Ājīvika was a Śramaṇa movement started by Makkhali Gosala. It was a big competitor to early Buddhism and Jainism.

The original writings of the Ājīvika school are lost. We know about their ideas from what ancient Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist texts say about them, often in a critical way. The Ājīvika school is known for its idea of Niyati, which means absolute determinism or fate. They believed there is no free will. Everything that has happened, is happening, and will happen is already decided by cosmic rules. Ājīvika thinkers thought the idea of karma was wrong. They were atheists and rejected the Vedas. However, they did believe that every living thing has an ātman (soul), which is also a main idea in Hinduism and Jainism.

Ajñana: The skeptics

Ajñana was a Śramaṇa school of extreme skepticism in India. It was a rival to early Buddhism and Jainism. They believed it was impossible to know about deep philosophical questions or to know if philosophical ideas were true. Even if knowledge was possible, they thought it was useless and didn't help with final freedom. They were seen as clever debaters who could argue against any idea but didn't offer their own positive beliefs. Jayarāśi Bhaṭṭa, who wrote a skeptical book, is seen as an important Ajñana philosopher.

Buddhist philosophies: Freedom from suffering

Buddhist philosophy started with the ideas of Gautama Buddha (who lived between the sixth and fourth centuries BCE). His teachings are found in early Buddhist texts. Buddhist thought spread across Asia through the silk road. It is now the main philosophy in Tibet and Southeast Asian countries like Sri Lanka and Burma.

Buddhism's main goal is to free people from dukkha (unease or suffering). Because not knowing the true nature of things causes suffering, Buddhist thinkers looked into how we gain knowledge and use reason. Key Buddhist ideas include the Four Noble Truths, Anatta (the idea of "not-self," meaning there's no fixed personal identity), and Anicca (the idea that all things are always changing). Buddhist thinkers have explored many topics like ethics, logic, and the philosophy of time.

Later Buddhist traditions developed complex ideas about the mind, called 'Abhidharma'. Mahayana philosophers like Nagarjuna and Vasubandhu created theories about Shunyata (the emptiness of all things) and Vijnapti-matra (appearance only). The Dignāga school developed a complex way of gaining knowledge and Buddhist logic. This school greatly influenced Indian philosophy. Through the work of Dharmakirti, this Buddhist logic became the main way of thinking in Tibetan Buddhist philosophy.

After Buddhism mostly left India, these philosophies kept growing in Tibetan, East Asian, and Theravada Buddhist traditions. In China, new ideas came from thinkers like Xuangzang and Zhiyi.

Buddhist modernism: New ways of thinking

In modern times, Buddhist modernism and Humanistic Buddhism appeared, influenced by Western ideas. Western Buddhism also grew, influenced by modern psychology and Western philosophy. Important modern Buddhist thinkers include Anagarika Dharmapala and D. T. Suzuki. Buddhist modernism means new forms of Buddhism that have come from interacting with modern culture and ideas. These modernists were influenced by ideas like the Enlightenment and Western science. A new Buddhist movement was started by the Indian leader B. R. Ambedkar in the 1950s, focusing on social and political changes.

Buddhist modernism includes movements like Humanistic Buddhism (which focuses on Buddhism for human life and tries to be free of supernatural beliefs), Secular Buddhism, and Engaged Buddhism.

Sikh philosophy: One God, selfless service

Sikhism is an Indian religion started by Guru Nanak (1469–1539) in the Punjab region during the Mughal Empire. Their main holy book is the Guru Granth Sahib. Sikhs believe in constantly meditating on God's name, being guided by the Guru, living a normal family life (not becoming a monk), doing what is right, treating all people equally, and believing in God's grace. Key ideas include Simran (remembering God), Sewa (selfless service), the Three Pillars of Sikhism, and the Five Thieves (vices to overcome).

Modern Indian philosophy: East meets West

In the 19th century, as India interacted with colonialism and Western philosophy, new ways of thinking developed. These are called Neo-Vedanta and Hindu modernism. These ideas focused on the universal nature of Indian philosophy (especially Vedanta) and the unity of different religions. During this time, Hindu modernists presented a single, ideal "Hinduism". They were also influenced by Western ideas. The Brahmo Samaj movement, led by Ram Mohan Roy, was one of the first. Swami Vivekananda was very important in spreading these new Hindu ideas and bringing them to the West. Modern Hindu thought also influenced Western culture through people like Vivekananda and the Theosophical Society.

The political ideas of Hindu nationalism are also important in modern Indian thought. The work of Mahatma Gandhi, Rabindranath Tagore, and others has had a big impact.

Jainism also had modern thinkers and defenders like Virchand Gandhi and Shrimad Rajchandra (who was a spiritual guide to Mahatma Gandhi).

East Asian philosophies: Ancient wisdom and new ideas

East Asian philosophy began in Ancient China. Chinese philosophy started during the Western Zhou Dynasty. After its fall, many different schools of thought, called the "Hundred Schools of Thought", grew (6th century to 221 BCE). This was a time of great intellectual growth. Major Chinese philosophies like Confucianism, Legalism, and Daoism appeared. Other less famous schools also existed. These philosophies developed ideas about reality, politics, and ethics. Along with Chinese Buddhism, they greatly influenced the rest of East Asia. Buddhism came to China during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) through the Silk Road and slowly developed unique Chinese forms like Chan (Zen).

Chinese philosophy: Key traditions

Confucianism: Harmony and good behavior

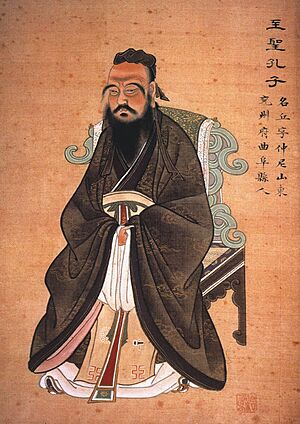

Confucianism is a Chinese way of thinking that includes rules for behavior, morals, and religious practices. It grew from the teachings of Confucius (551–479 BCE), who wanted to pass on the values of his ancestors. Other important Confucian thinkers include Mencius and Xun Kuang, who had different ideas about human nature.

Confucianism focuses on human values like family and social harmony, filial piety (respect for elders), Rén (kindness), and Lǐ (a system of proper behavior). Confucians believed these values came from a higher principle called Heaven. They also believed in spirits or gods.

Confucianism became a main idea for the government during the Han dynasty. It was revived as Neo-Confucianism during the Tang dynasty. Later, in the Song dynasty and Ming Dynasty, and in Korea, Neo-Confucianism became the main way of thinking. Thinkers like Zhu Xi and Wang Yangming were very important. Confucian texts were used for government exams. Confucianism faced challenges in the 20th century but is now seeing a revival, called New Confucianism.

East Asian cultures, including China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, have been greatly shaped by Confucianism.

Legalism: Strict laws and strong government

Legalism was a philosophy that focused on laws, practical politics, and how to manage government workers. They didn't care much about morals or ideal societies. Instead, they focused on making the government strong and stable through the power of the ruler and the state. Their goal was to create more order and security.

Key figures include Shen Buhai and Shang Yang. Shang Yang helped the Qin state become so powerful that it conquered all of China in 221 BCE. Han Fei brought together the ideas of other Legalists in his book, the Han Feizi. This book became a guide for Chinese leaders on how to run the state and organize the government.

Mohism: Impartial care for all

Mohism was a major school of thought founded by Mozi (c. 470–391 BCE). It was a rival to Confucianism and Taoism during ancient times. The main text is the Mozi. Mohist ideas about government were later used by Legalism, and their ethics were absorbed into Confucianism. Mohism mostly disappeared as a separate school after the Qin dynasty.

Mohism is best known for "impartial care." Mozi believed people should care for everyone equally, no matter their relationship. He also wanted government jobs to be given based on talent, not family ties. Mozi was against Confucian rituals. He focused on practical survival through farming, defense, and good government. He believed that traditions could be wrong, and people needed a guide to know which ones were good. This guide should promote actions that benefit everyone. Mozi linked his ideas to the "Will of Heaven," but his philosophy was more like utilitarianism (doing what is best for the most people).

Mohism was also connected to the School of Names, which focused on language, definitions, and logic.

Taoism: The way of nature

Taoism (or Daoism) is a term for different philosophies and religious systems that focus on living in harmony with the Tao (meaning "the Way"). The Tao is seen as the source and pattern of everything that exists. Taoism often emphasizes ideas like wu wei (effortless action), ziran (naturalness), pu (simplicity), and spontaneity. It places less importance on strict rules and rituals, unlike Confucianism. For many Taoists, achieving immortality through special practices was an important goal.

Early Taoism developed in the 4th century BCE. It was influenced by ideas from the School of Naturalists, which combined yin-yang and the Five Elements.

The Dao De Jing (traditionally by Laozi) and the Zhuangzi are the main texts of Taoism. The first organized form of Taoism, the Celestial Masters' school, appeared in the 2nd century CE. Xuanxue ("deep learning" or "Neo-Taoism") was a big philosophical movement that studied the Yijing, Daodejing, and Zhuangzi. It was popular from the 3rd to 6th centuries CE. Important thinkers of this movement included He Yan and Wang Bi, who focused on "Wu" (nothingness) as the deep nature of Tao.

Other Taoist schools became important throughout Chinese history, and later Taoist traditions were also influenced by Chinese Buddhism.

Modern East Asian philosophy: New directions

Chinese: Blending old and new

Modern Chinese thought comes from Classical Confucianism, Neo-Confucianism, Buddhism, Daoism, and "Western Learning" (Xixue), which appeared in the late Ming Dynasty.

The Opium War of 1839–42 was a humiliating time for China, as Western and Japanese powers invaded and took advantage of the country. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Chinese thinkers like Zhang Zhidong looked to Western practical knowledge to save traditional Chinese culture. He called this idea "Chinese Learning as Substance and Western Learning as Function."

Meanwhile, traditional thinkers tried to revive and strengthen old Chinese philosophies. Chinese Buddhist thought was promoted by thinkers like Yang Rensan. Another important movement is New Confucianism. This is a traditional revival of Confucian thought in China that started in the 20th century. Key New Confucians include Xiong Shili and Fung Youlan.

Japanese: Modernization and tradition

Modern Japanese thought is greatly influenced by Western science and philosophy. Japan quickly modernized partly because it studied Western science (called Rangaku) during the Edo period (1603–1868). Another movement, Kokugaku (national study), focused on ancient Japanese thought and culture, rather than foreign Chinese and Buddhist ideas. Motoori Norinaga was a key figure who said the heart of classic Japanese literature was a feeling called mono no aware ("sorrow at things passing").

In the Meiji period (1868–1912), the Meirokusha intellectual group promoted European Enlightenment ideas. Philosophers like Fukuzawa Yukichi tried to mix Western ideas with Japanese culture and values. The Shōwa period (1926–1989) saw the rise of State Shinto and Japanese nationalism.

Japanese Buddhist philosophy was influenced by the Kyoto School, which combined Western philosophers (especially German) with Buddhist thought. This school included Kitaro Nishida and Keiji Nishitani.

North Korean: Juche, self-reliance

Juche, usually meaning "self-reliance," is the official political idea of North Korea. The government says it is Kim Il-Sung's "original and revolutionary contribution to thought." The idea states that a person is "the master of his destiny" and that the North Korean people are the "masters of the revolution and construction."

Eastern and Western philosophy: Blending ideas

In modern times, many people have tried to combine Western and Eastern philosophical traditions.

Arthur Schopenhauer developed a philosophy that mixed Hinduism with Western thought. He believed the Upanishads (Hindu scriptures) would have a big impact in the West. However, he used older, sometimes flawed translations, so he might not have fully understood the Eastern philosophies.

More recently, the Kyoto School of philosophers combined the study of experience (phenomenology) from Husserl with ideas from Zen Buddhism. Watsuji Tetsurô, a 20th-century Japanese philosopher, tried to mix the works of Søren Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Heidegger with Eastern philosophies. Some people think there's an Eastern element in Heidegger's philosophy, especially as he tried to translate the Tao Te Ching into German.

The 20th-century Hindu guru Sri Aurobindo was influenced by German Idealism. His integral yoga is seen as a mix of Eastern and Western thought.

After the Xinhai Revolution in 1911 and the end of the Qing Dynasty, the May Fourth Movement wanted to get rid of old Chinese ways. There were two main philosophical trends then. One was against tradition and promoted Western ideas. Yan Fu translated many Western philosophical works. There were also efforts to bring Western ideas of democracy into Chinese political philosophy, especially by Sun Yat-Sen. Another important modern Chinese philosopher was Hu Shih, who promoted a form of pragmatism.

Marxism has had a huge influence on modern Chinese political thought, especially through Mao Zedong. Maoism is a Chinese Marxist philosophy based on Mao's teachings. It focuses on a revolution led by farmers and a decentralized farming economy. The current government of China still supports a practical form of socialism called Socialism with Chinese characteristics. When the Chinese Communist Party took power, older philosophies like Taoism and Confucianism were criticized and later suppressed during the Cultural Revolution.

The Swiss psychologist Carl Jung was deeply influenced by the I Ching (Book of Changes), an ancient Chinese text used for telling the future. It uses a system of Yin and Yang. Carl Jung's idea of synchronicity (meaningful coincidences) is similar to an Eastern view of how things are connected, not just cause and effect.

Thinking about "Eastern philosophy"

Some thinkers, like Victoria S. Harrison, say that the idea of "Eastern philosophy" was created by Western scholars in the 1800s. This is because in Asia, there isn't just one single philosophy. Instead, there are many different traditions that have met and influenced each other over time.

Some Western thinkers have claimed that true philosophy only comes from Western cultures. For example, the German philosopher Martin Heidegger reportedly said that only Greek and German languages were good for philosophizing. In many Western universities, only Western philosophy is taught, and Asian philosophy is often ignored or seen as less important. However, others argue that a broader definition of philosophy should include both Western and Asian thought equally.

See also

In Spanish: Filosofía oriental para niños

In Spanish: Filosofía oriental para niños

- Eastern Ethics in Business

- Middle Eastern philosophy

- Eastern religions