History of Argentina facts for kids

The history of Argentina is a long and interesting story that can be divided into four main parts. First, there's the early history, before Europeans arrived (up to the 1500s). Then came the colonial period, when Spain ruled (1536–1809). After that, Argentina worked to become its own country (1810–1880). Finally, there's the history of modern Argentina (from about 1880 until today).

The very first people settled in what is now Argentina about 13,000 years ago, in the southern part called Patagonia. Written history began when Spanish explorers arrived in 1516, led by Juan Díaz de Solís, exploring the Río de la Plata. This marked the start of Spain's control over the region.

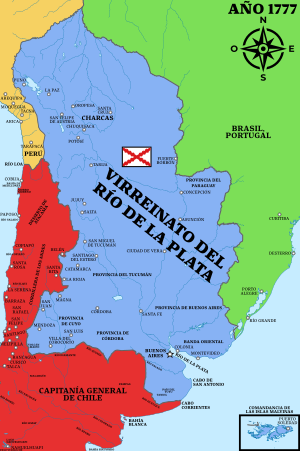

In 1776, the Spanish Crown created the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. This was a large area that included parts of what are now Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Bolivia. In May 1810, the May Revolution began, leading to the gradual formation of independent states, including the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. Argentina declared its independence on July 9, 1816, and after defeating the Spanish Empire in 1824, a federal state was formed between 1853 and 1861. Today, this country is known as the Argentine Republic.

Contents

- Early History (Before Europeans)

- Spanish Colonial Era

- War of Independence

- Historical Map

- Argentine Civil Wars

- Liberal Governments (1862–1880)

- Conservative Republic (1880–1916)

- Radical Governments (1916–1930)

- Infamous Decade (1930–1943)

- Revolution of 1943 (1943–1946)

- Peronist Years (1946–1955)

- Revolución Libertadora (1955–1958)

- Fragile Radical Administrations (1958–1966)

- Revolución Argentina (1966–1973)

- Growing Instability (1969–1976)

- National Reorganization Process (1976–1983)

- New Democracy (1983–Present)

- See also

Early History (Before Europeans)

The land that is now Argentina didn't have many people living in it before Europeans arrived. The oldest signs of human life here are from the Paleolithic period (Old Stone Age), and there are more signs from the Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) and Neolithic (New Stone Age) periods. However, large areas were empty for a long time between 4000 and 2000 B.C. because of a very dry period.

Archaeologists have grouped the indigenous peoples in Argentina into three main types. The first group were basic hunters and gatherers who didn't make pottery. They lived in the Pampas and Patagonia. The second group were advanced gatherers and hunters, like the Charrúa and Minuane people, and the Guaraní. The third group were basic farmers who did make pottery.

In the late 1400s, the Inca Empire, led by Topa Inca Yupanqui, conquered some native tribes in the Quebrada de Humahuaca region. They did this to get metals like silver, zinc, and copper. The Incas ruled this area for about 50 years, until the Spanish arrived in 1536.

Farming was practiced in some parts of Argentina before the Spanish came, as far south as Mendoza Province. Sometimes, people in nearby parts of Patagonia also farmed, but they would often go back to hunting and gathering. By the time the Spanish arrived in the 1550s, there was no record of farming in northern Patagonia. The vast Patagonian grasslands and lots of guanaco (a type of llama) probably encouraged people to keep living as hunter-gatherers.

Spanish Colonial Era

Europeans first explored this region in 1502 with Portuguese sailors. In 1516, the Spanish, led by Juan Díaz de Solís, visited the area that is now Argentina. In 1536, Pedro de Mendoza started a small settlement where Buenos Aires is today, but it was abandoned in 1541.

A second settlement in Buenos Aires was established in 1580 by Juan de Garay. Córdoba was founded in 1573 by Jerónimo Luis de Cabrera. These areas were part of the Viceroyalty of Peru, with its capital in Lima. Settlers came from Lima. Unlike other parts of South America, the colonization of the Río de la Plata wasn't driven by a search for gold, because there weren't any precious metals to mine.

The natural ports on the Río de la Plata could not be used for official trade because all goods had to go through the port of Callao near Lima. This rule led to a lot of illegal trade in cities like Asunción, Buenos Aires, and Montevideo.

Spain increased the importance of this region by creating the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata in 1776. This new viceroyalty included what is now Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, and much of Bolivia. Buenos Aires became a busy port because it controlled customs for the new region. Money from the Potosí mines, increasing trade in goods (not just precious metals), and the production of cattle for export (like leather) helped Buenos Aires become a very important trade center.

However, the viceroyalty didn't last long. Its different regions weren't united, and Spain didn't support it enough. Ships from Spain became rare after Spain lost the battle of Trafalgar, which gave Britain control of the seas. The British tried to invade Buenos Aires and Montevideo in 1806 and 1807, but they were defeated by Santiago de Liniers. These victories, achieved without help from Spain, made the people of Buenos Aires feel more confident.

When the Peninsular War started in Spain and the Spanish king Ferdinand VII was captured, it caused great concern in the viceroyalty. People thought that without a king, they should rule themselves. This idea led to several attempts to remove local authorities, but they didn't last. A successful attempt, the May Revolution of 1810, happened when news arrived that almost all of Spain had been conquered.

War of Independence

The May Revolution removed the Spanish viceroy. For a short time, people considered other forms of government, like having a king or a regent. The viceroyalty was also renamed the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. However, the different territories changed their status many times during the war. Some regions stayed loyal to Spain, while others were captured or recaptured. Later, these regions would split into several different countries.

The first military campaigns against those loyal to Spain were led by Manuel Belgrano and Juan José Castelli. The first government, the Primera Junta, grew into the Junta Grande, and then was replaced by the First Triumvirate. Years later, a Second Triumvirate took over. This group called for the Assembly of year XIII, which was supposed to declare independence and write a constitution. However, it didn't do either. Instead, it replaced the triumvirates with a single leader called the Supreme Director.

Around this time, José de San Martín arrived in Buenos Aires with other generals who had fought in the Peninsular War. They brought new energy to the fight for independence. San Martín created the Army of the Andes in Mendoza. With the help of Bernardo O'Higgins and other Chileans, he made the famous Crossing of the Andes and helped liberate Chile. Using the Chilean navy, he then moved to Peru and helped liberate that country too. San Martín later met Simón Bolívar at Guayaquil and then retired from the fight.

A new assembly, the Congress of Tucumán, was called while San Martín was preparing to cross the Andes. It finally declared independence from Spain and any other foreign power. Bolivia declared its independence in 1825, and Uruguay became a separate country in 1828 after the Cisplatine War.

The French-Argentine Hippolyte Bouchard sailed his fleet to fight Spain overseas. He attacked Spanish California, Chile, Peru, and the Philippines. He gained the support of escaped Filipinos in San Blas who joined the Argentine navy because they shared grievances against Spanish rule. Later, the Argentine Sun of May was used as a symbol by Filipinos in their own revolution against Spain. Bouchard also secured Argentina's diplomatic recognition from King Kamehameha I of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Hawaii was the first state to recognize Argentina's independence.

The United Kingdom officially recognized Argentina's independence in 1825 by signing a Treaty of Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation. Spain did not recognize Argentina's independence for several more decades.

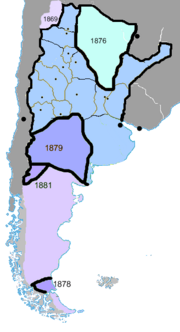

Historical Map

The map below shows how the territory of Argentina changed in the 1800s. It's based on old maps and gives a general idea of the changes. The hatched areas were disputed or changed during these times. The text in this article explains these changes. There are also minor territory changes not shown on the map.

Argentine Civil Wars

After defeating Spain, Argentina faced a long civil war. This was between two groups: the Unitarians and the Federalists. They disagreed on how the country should be organized and what role Buenos Aires should play. Unitarians believed Buenos Aires should lead the less developed provinces with a strong centralized government. Federalists, however, thought the country should be a federation of independent provinces, similar to the United States. During this time, the government sometimes arrested protesters and questioned them.

During this period, the United Provinces of the Rio de la Plata didn't have a single head of state. The Unitarians' defeat at the Battle of Cepeda ended the authority of the Supreme Directors and the 1819 Constitution. In 1826, there was another attempt to write a constitution, which led to Bernardino Rivadavia being named President of Argentina. But the provinces rejected it. Rivadavia resigned because of problems during the Cisplatine War, and the 1826 constitution was canceled.

During this time, the Governors of Buenos Aires Province were given the power to handle the confederation's international relations, including wars and paying debts. The most powerful person during this period was the Federalist Juan Manuel de Rosas. Historians have different views of him: some see him as a strong ruler, while others praise him for defending national independence.

Rosas ruled the province of Buenos Aires from 1829 to 1852. He faced military threats from groups trying to break away, neighboring countries, and even European nations. Although Rosas was a Federalist, he kept the customs money from Buenos Aires under the city's control. Other provinces expected to share this money. Rosas believed this was fair because only Buenos Aires was paying the external debt from loans and the wars of independence and against Brazil. He also created his own special force called the "Mazorca."

Rosas didn't want to call a new assembly to write a constitution. This led General Justo José de Urquiza from Entre Ríos to turn against him. Urquiza defeated Rosas in the battle of Caseros and then called for such an assembly. The Argentine Constitution of 1853 is still in use today, with some changes. Buenos Aires didn't immediately accept the Constitution and left the Confederation, but it rejoined a few years later. In 1862, Bartolomé Mitre became the first president of the unified country.

Liberal Governments (1862–1880)

During Bartolomé Mitre's presidency, Argentina's economy improved. Farming became more modern, foreign countries invested money, new railroads and ports were built, and many people immigrated from Europe. Mitre also made the political system more stable by sending federal troops to defeat the armies of local leaders like Chacho Peñaloza and Juan Sáa. Argentina joined Uruguay and Brazil against Paraguay in the War of the Triple Alliance. This war ended during Sarmiento's time, with Paraguay's defeat and Argentina gaining some of its territory.

Even though Argentina won the war, Mitre's popularity dropped a lot. Many Argentines were against the war because it meant allying with Brazil (Argentina's old rival) and betraying Paraguay (which had been an important economic partner). A key part of Mitre's presidency was the "Law of Compromise." This law allowed Buenos Aires to join the Argentine Republic and let the government use Buenos Aires City as its center. However, it didn't make Buenos Aires a federal district and allowed the province to leave the nation if there was a conflict.

In 1868, Domingo Faustino Sarmiento became president after Mitre. Sarmiento strongly supported public education, culture, and telegraphs. He also modernized the Army and Navy. Sarmiento managed to defeat the last remaining local leaders and dealt with the problems left by the Triple Alliance War. These problems included a drop in national production because thousands of soldiers died, and outbreaks of diseases like cholera and yellow fever brought back by returning soldiers.

In 1874, Nicolás Avellaneda became president. He faced economic difficulties caused by the Panic of 1873. Most of these economic problems were solved when new land became available for development. This happened after the country expanded its territory through the Conquest of the Desert, led by his war minister Julio Argentino Roca. This military campaign took most of the lands controlled by native peoples and reduced their population.

In 1880, a trade conflict caused problems in Buenos Aires. This led Governor Carlos Tejedor to declare that Buenos Aires was leaving the republic. Avellaneda refused this right, breaking the Law of Compromise. He sent army troops led by Roca to take control of the province. Tejedor's efforts to secede were defeated, and Buenos Aires permanently joined the republic. The city of Buenos Aires became a federal district and the nation's capital.

Conservative Republic (1880–1916)

After becoming very popular because of his successful desert campaign, Julio Argentino Roca was elected president in 1880. He was the candidate for the National Autonomist Party (PAN), which stayed in power until 1916. During his time as president, Roca built many political alliances and put in place measures that helped him keep almost complete control of Argentine politics throughout the 1880s. His skill in political strategy earned him the nickname "The Fox."

The country's economy improved as it shifted from extensive farming to industrial agriculture. There was also a huge wave of European immigration. However, there wasn't a strong move towards industrialization yet. At that time, Argentina received a lot of foreign investment, more than most other Latin American countries. During this economic growth, the Law 1420 of Common Education was passed in 1884. This law made education free, non-religious, and available to all children. The Roman Catholic Church in Argentina strongly opposed this and other government policies. This led the Holy See (the Pope's government) to break off diplomatic relations with Argentina for several years, setting the stage for decades of tension between the Church and the state.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Argentina temporarily solved its border disputes with Chile. This happened with agreements like the Puna de Atacama dispute in 1899, the Boundary Treaty of 1881 between Chile and Argentina, and the 1902 General Treaty of Arbitration. Roca's government and those that followed were closely linked to the Argentine oligarchy, especially the large landowners.

In 1888, Miguel Juárez Celman became president because Roca was not allowed to be re-elected by the constitution. Celman tried to reduce Roca's control over politics, which made Roca oppose him. Roca led a large opposition movement against Celman. This, combined with the bad effects of the Long Depression on Argentina's economy, allowed the Civic opposition party to start a coup, known as the Revolution of the Park. Although the revolution didn't achieve its main goals, it forced Juárez Celman to resign and marked the decline of the Generation of '80.

In 1891, Roca suggested that the Civic Union choose someone to be vice-president for his next presidency. One group, led by Mitre, agreed to the deal, while another group, led by Leandro Alem, was against it. This led to the Civic Union splitting into the National Civic Union (Argentina), led by Mitre, and the Radical Civic Union, led by Alem. After this split, Roca withdrew his offer, having successfully divided the Civic Union and reduced their power. Alem died in 1896, and control of the Radical Civic Union went to his nephew, Hipólito Yrigoyen.

After Celman's downfall, his vice-president Carlos Pellegrini took over. He worked to solve the economic crisis affecting the country, earning him the nickname "The Storm Sailor." Fearing another wave of opposition from Roca, like the one Celman faced, Pellegrini remained moderate during his presidency. He ended his predecessor's efforts to distance "The Fox" from political control. The governments that followed until 1898 took similar steps and sided with Roca to avoid political trouble.

In 1898, Roca became president again. The country was politically unstable, with many social conflicts, including large strikes and attempts at anarchist uprisings. Roca handled most of these conflicts by having the police or army crack down on protesters and suspected rebels. After his second presidency ended, Roca became ill, and his role in political affairs gradually decreased until he died in late 1914.

In 1904, Alfredo Palacios, a member of Juan B. Justo's Socialist Party (founded in 1896), became the first Socialist representative in Argentina. He represented the working-class neighborhood of La Boca in Buenos Aires. He helped create many laws, regulating child and woman labor, working hours, and Sunday rest.

The revolts by the Unión Cívica Radical in 1893 and 1905, led by Hipólito Yrigoyen, made the ruling class fear more social instability and a possible revolution. Roque Sáenz Peña, a progressive member of the PAN, realized the need to meet public demands to keep the existing system. After being elected president in 1910, he passed the Sáenz Peña Law in 1912. This law made voting mandatory, secret, and universal for males aged 18 or older. His goal was not to let the Radical Civic Union take power, but to increase public support for the PAN by allowing more people to vote. However, the result was the opposite: the next election in 1916 chose Hipólito Yrigoyen as president, ending the PAN's long rule.

Radical Governments (1916–1930)

Conservative groups controlled Argentine politics until 1916. That year, the Radicals, led by Hipólito Yrigoyen, won control of the government in the first national elections where all men could vote. About 745,000 citizens were allowed to vote out of a total population of 7.5 million (immigrants, who made up a large part of the population, were not allowed to vote). Of those, 400,000 did not vote.

Yrigoyen only got 45% of the votes, which meant he didn't have a majority in Parliament. Conservatives remained the strongest group there. Because of this, out of 80 laws proposed by the president, only 26 were passed by the conservative majority. A plan for moderate farming reform was rejected, as were an income tax on interest and the idea of creating a Bank of the Republic (which would act like today's Central Bank).

Meanwhile, the Radicals kept Argentina neutral during World War I, even though the United States urged them to declare war against the Central Powers. Being neutral allowed Argentina to export goods to Europe, especially to Great Britain, and to lend money to the countries fighting the war. Germany sank two Argentine civilian ships, the Monte Protegido in April 1917 and the Toro. The diplomatic incident ended only with the German ambassador being sent home. Yrigoyen organized a meeting of neutral countries in Buenos Aires to oppose the United States' attempt to bring American states into the European war. He also supported Sandino's resistance in Nicaragua.

Despite conservative opposition, the Radical Civic Union (UCR) focused on fair elections and democratic institutions. They welcomed Argentina's growing middle class and other social groups who had not been in power before. Yrigoyen's goal was to "fix" the system by making necessary changes that would help the country's farming and export economy continue. He balanced moderate social reforms with putting down social movements. In 1918, a student movement began at the University of Córdoba. This led to the University Reform, which quickly spread across Latin America.

The Tragic Week in January 1919 began when the Argentine Regional Workers' Federation (FORA) called for a general strike after a police shooting. This event resulted in 700 people killed and 4,000 injured. General Luis Dellepiane marched into Buenos Aires to restore order. Although some people wanted him to overthrow Yrigoyen, he remained loyal to the President, on the condition that he could freely stop the protests. Social movements continued later at the Forestal British company and in Patagonia, where Hector Varela led military crackdowns, helped by the Argentine Patriotic League, killing 1,500 people.

On the other hand, Yrigoyen's government passed the Labor Code in 1921, which established the right to strike. It also put in place minimum wage laws and collective contracts. His government also started the Dirección General de Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales (YPF), the state oil company, in June 1922. The Radical party rejected the idea of class struggle and promoted social cooperation.

In September 1922, Yrigoyen's government refused to follow the cordon sanitaire policy against the Soviet Union. Instead, based on the help given to Austria after the war, Argentina decided to send 5 million pesos in aid to the USSR.

The same year, Yrigoyen was replaced by his rival within the UCR, Marcelo Torcuato de Alvear, an aristocrat. Alvear defeated Norberto Piñero's Concentración Nacional (conservatives) with 458,457 votes to 200,080. Alvear brought people from the traditional ruling classes into his cabinet. Alvear's supporters formed the Unión Cívica Radical Antipersonalista, which was against Yrigoyen's party.

In the early 1920s, the anarchist movement grew, fueled by new immigrants and people deported from Europe. This led to a new wave of left-wing activism in Argentina. These new leftists, mostly anarchists and anarcho-communists, rejected the slow progress of the old Radical and Socialist groups in Argentina. They wanted immediate action. A series of bombings and shootouts with police happened. This included an attempt to assassinate U.S. President Herbert Hoover during his visit to Argentina in 1928, and a nearly successful attempt to assassinate Yrigoyen in 1929 after he was re-elected.

In 1921, the Logia General San Martín was founded. This group spread nationalist ideas in the military until it was dissolved in 1926. Three years later, the Liga Republicana (Republican League) was founded by Roberto de Laferrère, inspired by Benito Mussolini's Blackshirts in Italy. The Argentine Right found its main influences in the 19th-century Spanish writer Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo and the French royalist Charles Maurras. Also in 1922, the poet Leopoldo Lugones, who had turned towards fascism, gave a famous speech in Lima. This speech, known as "the time of the sword," called for a military coup and a military dictatorship. The War Minister and future dictator Agustín P. Justo was present at this speech.

In 1928, Yrigoyen was re-elected president and began making reforms to increase workers' rights. This made conservative opposition against Yrigoyen even stronger. The opposition grew even more after Argentina was hit hard by the start of the Great Depression following the Wall Street Crash. On September 6, 1930, a military coup led by the pro-fascist general José Félix Uriburu overthrew Yrigoyen's government. This began a period in Argentine history known as the Infamous Decade.

During the Great Depression, exports of frozen beef, especially to Great Britain, provided much-needed foreign money, but trade dropped sharply.

Infamous Decade (1930–1943)

In 1929, Argentina was a wealthy country by world standards. But this prosperity ended after 1929 with the worldwide Great Depression. In 1930, a military coup, supported by the Argentine Patriotic League, forced Hipólito Yrigoyen out of power. He was replaced by José Félix Uriburu. Support for the coup grew because of Argentina's struggling economy and a series of bomb attacks and shootings involving radical anarchists. These events upset moderate people in Argentina and angered the conservative right, who had been pushing for strong action by the military.

The military coup started a period known as the "Infamous Decade." This time was marked by electoral fraud, the persecution of political opposition (mainly against the UCR), and widespread government corruption, all happening during the global depression.

During his short time as president, Uriburu severely cracked down on anarchists and other far-left groups. This resulted in 2,000 illegal executions of members of anarchist and communist groups. The most famous execution was that of Severino Di Giovanni, who was captured in January 1931 and executed on February 1 of the same year.

After becoming president through the coup, Uriburu tried to change the constitution to include corporatism. This move towards fascism was not liked by the conservative supporters of the coup. They then shifted their support to the more moderate conservative general Agustín P. Justo, who won the presidency in a heavily fraudulent election in 1932.

Justo began economic policies that mainly benefited the country's upper classes. These policies also allowed a lot of political and industrial corruption, which hurt national growth. One of the most criticized decisions of Justo's government was the Roca–Runciman Treaty between Argentina and the United Kingdom. This treaty benefited the British economy and the wealthy beef producers in Argentina.

In 1935, the progressive Senator Lisandro de la Torre began an investigation into corruption claims within the Argentine beef industry. During this investigation, he tried to accuse Justo's Minister of Agriculture, Luis Duhau, and the Minister of Finance, Federico Pinedo, of corruption and fraud. During the investigation's presentation in Congress, Duhau started a fight among the senators. His bodyguard, Ramón Valdez-Cora, tried to kill De La Torre but accidentally shot De La Torre's friend and political partner Enzo Bordabehere. The meat investigation was stopped soon after, but De La Torre did manage to get the head of the Anglo meat company jailed for corruption.

The collapse of international trade led to industrial growth focused on replacing imports. This helped Argentina become more economically independent. Political conflict increased, marked by clashes between right-wing fascists and left-wing radicals, while military-oriented conservatives controlled the government. Although many claimed the elections were fraudulent, Roberto Ortiz was elected president in 1937 and took office the next year. However, due to his poor health, he was succeeded by his vice-president, Ramón Castillo. Castillo effectively took power in 1940 and formally became leader in 1942.

Revolution of 1943 (1943–1946)

The civilian government seemed close to joining the Allies in World War II. However, many officers in the Argentine armed forces (and ordinary citizens) objected because they feared the spread of communism. There was wide support to stay neutral in the conflict, just like during World War I. The government was also criticized for its domestic policies, including electoral fraud, poor labor rights, and the choice of Patrón Costas to run for president.

On June 4, 1943, the United Officers' Group (GOU), a secret alliance of military leaders including Pedro Pablo Ramírez, Arturo Rawson, Edelmiro Farrell, and Farrell's protégé Juan Perón, marched to the Casa Rosada (the presidential palace). They demanded President Castillo's resignation. After hours of threats, their goal was achieved, and the president resigned. Historians consider this event the official end of the Infamous Decade.

After the coup, Ramírez took power. Although he did not declare war, he broke off relations with the Axis powers. Argentina's largest neighbor, Brazil, had already entered the war on the Allied side in 1942.

In 1944, Ramírez was replaced by Farrell, an army officer of Irish-Argentine background who had spent two years with Mussolini's army in the 1920s. Initially, his government remained neutral. Towards the end of the war, Farrell decided it was in Argentina's best interest to be on the winning side. Like several Latin American states, Argentina made a late declaration of war against Germany on March 27, 1945, as Germany was quickly collapsing.

Juan Perón managed relations with workers and unions, and became very popular. He was removed from office and detained on Martín García Island. However, a huge demonstration on October 17, 1945, forced the government to free Perón and restore him to his position. Perón would win the elections shortly afterward by a large margin. The US ambassador, Spruille Braden, directly supported the anti-Peronist parties in Argentine politics.

Peronist Years (1946–1955)

In 1946, General Juan Perón became president. His popular political ideas became known as peronism. His popular wife, Eva Perón, played a very important political role until her death in 1952. Perón controlled information by closing down 110 publications between 1943 and 1946. During Juan Perón's rule, the number of unionized workers and government programs increased.

His government followed a policy of staying out of international conflicts and tried to reduce the political and economic influence of other nations, especially the United States. Perón increased government spending. His policies led to very high inflation. The peso lost about 70% of its value from early 1948 to early 1950; inflation reached 50% in 1951.

People who opposed him were imprisoned. He removed many important and capable advisors, promoting officials mainly based on their personal loyalty to him. A coup (Revolución Libertadora) led by Eduardo Lonardi, and supported by the Catholic Church, removed him from power in 1955. He went into exile, eventually settling in Spain.

Revolución Libertadora (1955–1958)

In Argentina, the 1950s and 1960s saw many coups d'état (military takeovers). The economy grew slowly in the 1950s and faster in the 1960s. Argentina continued to face demands from social groups and workers. Argentine painter Antonio Berni's artworks showed the social problems of these times, especially life in the villas miseria (shanty towns).

After the Revolución Libertadora military coup, Eduardo Lonardi held power only for a short time. He was replaced by Pedro Aramburu, who was president from November 13, 1955, to May 1, 1958. In June 1956, two Peronist generals, Juan José Valle and Raul Tanco, tried to overthrow Aramburu. They criticized a major removal of officers in the army, the cancellation of social reforms, and the persecution of trade union leaders. They also demanded the release of all political and labor activists and a return to constitutional rule. The uprising was quickly crushed. General Valle and other military members were executed, and twenty civilians were arrested in their homes.

Along with the June 1955 Casa Rosada bombing on the Plaza de Mayo, the León Suarez massacre was one of the important events that started a cycle of violence. Pedro Aramburu was later kidnapped and executed for this massacre in 1970 by Fernando Abal Medina, Emilio Angel Maza, Mario Firmenich, and others, who would later form the Montoneros movement.

In 1956, special elections were held to change the constitution. The Radical Party, led by Ricardo Balbín, won a majority. However, 25% of all ballots were left blank as a protest by the banned Peronist party. Also supporting Peronism, the left wing of the Radical Party, led by Arturo Frondizi, left the Constitutional Assembly. The Assembly was greatly weakened by this and was only able to restore the Constitution of 1853 with the addition of Article 14 bis, which listed some social rights.

Fragile Radical Administrations (1958–1966)

A ban on Peronist expression and representation continued during the unstable civilian governments from 1958 to 1966. Frondizi, the UCRI's candidate, won the presidential elections of 1958, getting about 4,000,000 votes compared to 2,500,000 for Ricardo Balbín (with 800,000 neutral votes). From Caracas, Perón supported Frondizi and asked his followers to vote for him. Perón hoped this would end the ban on the Peronist movement and bring back the workers' social laws passed during his leadership.

On one hand, Frondizi appointed Álvaro Alsogaray as Minister of Economy to please powerful farming groups and other conservatives. Álvaro, a member of the powerful military family Alsogaray, had already been Minister of Industry under Aramburu's military rule. He lowered the value of the peso and put controls on credit.

On the other hand, Frondizi followed a secular program, which worried Catholic nationalist groups. This led to the formation of the far-right Tacuara Nationalist Movement between 1960 and 1962.

The Tacuara, which was the "first urban guerrilla group in Argentina," carried out several anti-Semitic bombings. This happened especially after Adolf Eichmann was kidnapped by the Mossad in 1960. During Dwight Eisenhower's visit to Argentina in February 1962, the Tacuara led nationalist protests against him. This led to the imprisonment of several of their leaders, including Joe Baxter.

However, Frondizi's government ended in 1962 with another military intervention. This happened after Peronist candidates won a series of local elections. José María Guido, the chairman of the senate, claimed the presidency based on constitutional rules before the deeply divided armed forces could agree on a name. Right-wing groups in the Argentine armed forces, who wanted direct military rule and to suppress former Peronist politicians, later tried to take control of the government in the 1963 Argentine Navy Revolt on April 2. The plotters failed to gain the loyalty of army units near the capital, allowing Guido's government to quickly put down the revolt at the cost of 21 lives.

In new elections in 1963, neither Peronists nor Communists were allowed to participate. Arturo Illia of the Radical People's Party won these elections. Regional elections and special elections over the next few years favored Peronists.

On the other hand, Illia outlawed the Tacuara in 1965. Some of its members eventually joined the Peronist Left (like Joe Baxter), while others stayed in their far-right positions (like Alberto Ezcurra Uriburu, who would work with the Triple A).

Even though the country grew and developed economically during Illia's time as president, he was eventually removed in a military coup in 1966.

Revolución Argentina (1966–1973)

Amidst growing worker and student protests, another coup took place in June 1966. This coup called itself the Revolución Argentina (Argentine Revolution). It put General Juan Carlos Onganía in power as the de facto (in fact, but not by law) president. He was supported by several leaders of the General Confederation of Labour (CGT), including its general secretary, Augusto Vandor. This led to a series of military-appointed presidents.

Previous military coups aimed to set up temporary military governments. However, the Revolución Argentina, led by Onganía, aimed to create a new political and social order. This order was against both liberal democracy and communism. It gave the Armed Forces of Argentina a leading political role in organizing the country's economy. The political scientist Guillermo O'Donnell called this type of government an "authoritarian-bureaucratic state." He used this term for the Revolución Argentina, the Brazilian military regime (1964–1985), Augusto Pinochet's regime (starting in 1973), and Juan María Bordaberry's regime in Uruguay.

Onganía's Minister of Economy, Adalbert Krieger Vasena, froze wages and lowered the value of the currency by 40%. This greatly affected the Argentine economy, especially the farming sector, and favored foreign investment. Vasena stopped collective labor agreements. He also changed the oil law, which had given the state oil company Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales (YPF) a partial monopoly. He also passed a law that made it easier to evict people who failed to pay rent. Finally, the right to strike was suspended (Law 16,936), and several other laws reversed progress made in labor laws in previous years.

The workers' movement split into two groups. One group, the Vandoristas, supported a "Peronism without Peron" idea (Vandor said that "to save Perón, one has to be against Perón"). They wanted to negotiate with the military government. The other group were Peronists, who were also divided among themselves.

In July 1966, Onganía ordered the police to forcibly clear five buildings of the University of Buenos Aires (UBA) on July 29, 1966. This event is known as La Noche de los Bastones Largos ("The Night of the Long Batons"). These buildings had been occupied by students, professors, and graduates who were part of the university's self-governing body. They opposed the military government's interference in universities and its cancellation of the 1918 university reform. This repression led to 301 university professors going into exile, including Manuel Sadosky, Tulio Halperín Donghi, Sergio Bagú, and Risieri Frondizi.

In late May 1968, General Julio Alsogaray disagreed with Onganía, and rumors spread about a possible coup d'état, with Algosaray leading the conservative opposition to Onganía. Finally, at the end of the month, Onganía dismissed the leaders of the Armed Forces: Alejandro Lanusse replaced Julio Alsogaray, Pedro Gnavi replaced Benigno Varela, and Jorge Martínez Zuviría replaced Adolfo Alvarez.

On September 19, 1968, two important events affected Revolutionary Peronism. First, John William Cooke, Perón's former personal representative and a key thinker for the Peronist Left, died of natural causes. Second, a small group (13 men and one woman) who aimed to create a foco (a small group starting a revolution) in Tucumán Province to lead resistance against the military government was captured. Among them was Envar El Kadre, then a leader of the Peronist Youth.

In 1969, the General Confederation of Labour of the Argentines (CGTA), led by the graphic designer Raimundo Ongaro, led social movements, especially the Cordobazo, and other movements in Tucumán and Santa Fe. While Perón managed to reconcile with Augusto Vandor, head of the CGT Azopardo, he followed a careful approach of opposing the military government. He moderately criticized the government's economic policies but waited for discontent within the government. Perón said, "hay que desencillar hasta que aclare" (one must unsaddle until it clears), meaning to be patient. Thus, Onganía had a meeting with 46 CGT delegates, including Vandor, who agreed to cooperate with the military government.

In December 1969, more than 20 priests, members of the Movement of Priests for the Third World (MSTM), marched on the Casa Rosada to give Onganía a petition. They asked him to stop the planned removal of villas miserias (shanty towns).

Meanwhile, Onganía put in place corporatism policies, experimenting especially in Córdoba, under Carlos Caballero's governance. The same year, the Movement of Priests for the Third World issued a statement supporting socialist revolutionary movements. This led the Catholic hierarchy, through Juan Carlos Aramburu, the coadjutor archbishop of Buenos Aires, to forbid priests from making political or social statements.

Growing Instability (1969–1976)

During the military government of the Revolución Argentina, left-wing groups started to regain power through secret movements. This was mainly through violent guerrilla groups. Later, the return of Peronism was expected to calm things down, but it did the opposite. It created a violent split between right-wing and left-wing Peronists, leading to years of violence and political instability. This ended with the coup d'état in 1976.

Underground Movements (1969–1973)

Various armed actions, led by the Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación (FAL), happened in April 1969. These groups were made up of former members of the Revolutionary Communist Party. Several FAL members were arrested. These were the first left-wing urban guerrilla actions in Argentina. Besides these isolated actions, the Cordobazo uprising that year, called by the CGT de los Argentinos and its Cordobese leader, Agustín Tosco, caused protests across the country. The same year, the People's Revolutionary Army (ERP) was formed as the military branch of the Trotskyist Workers' Revolutionary Party. This group kidnapped wealthy Argentines and demanded ransom.

The last of the military presidents, Alejandro Lanusse, was appointed in 1971. He tried to bring back democracy while Peronist workers' protests continued. To calm the rising resistance, the military government was forced to make concessions. These included lifting the ban on Peronism, holding open elections in 1973, and funding state housing projects for shantytowns.

Cámpora's Time in Office (1973)

On March 11, 1973, Argentina held general elections for the first time in ten years. Perón was not allowed to run, but voters elected his stand-in, Dr. Hector Cámpora, as president. Cámpora defeated his Radical Civic Union opponent. Cámpora won 49.5 percent of the votes in the presidential election, campaigning on a promise of national rebuilding.

With huge public support, Cámpora began his term on May 25. He took office on May 25, which was celebrated by a massive gathering of the Peronist Youth movement, Montoneros, FAR, and FAP ("Fuerzas Armadas Peronistas") in the Plaza de Mayo. Cámpora took a strong stand against right-wing Peronists, saying during his first speech: "La sangre derramada no será negociada" ("Spilled blood will not be negotiated").

Cuban president Osvaldo Dorticós and Chilean president Salvador Allende were at his inauguration. However, William P. Rogers, U.S. Secretary of State, and Uruguayan president Juan Bordaberry, could not attend because they were blocked in their cars by protesters. Political prisoners were freed on the same day due to pressure from the demonstrators. Cámpora's government included progressive figures like Interior Minister Esteban Righi and Education Minister Jorge Taiana. But it also included members of the labor and political right-wing Peronist groups, such as José López Rega, Perón's personal secretary and Minister of Social Welfare, who was also a member of the P2 Masonic lodge. Perón's followers also had strong majorities in both houses of Congress.

Hector Cámpora's government followed traditional Peronist economic policies, supporting the national market and sharing wealth. One of José Ber Gelbard's first actions as minister of economics was to increase workers' wages. However, the 1973 oil crisis greatly affected Argentina's oil-dependent economy. Almost 600 social conflicts, strikes, or occupations happened in Cámpora's first month. The military accepted Cámpora's victory, but strikes and government-backed violence continued. The slogan "Campora in government, Perón in power" showed the true source of popular joy.

Perón's Return (1973–1974)

With increasing violence from both the right and left, Perón decided to return and become president. On June 20, 1973, two million people waited for him at Ezeiza airport. From Perón's speaking platform, hidden far-right gunmen fired into the crowd, shooting at the Peronist Youth movement and the Montoneros. At least thirteen people were killed and more than three hundred were injured. This event became known as the Ezeiza massacre.

Cámpora and vice-president Solano Lima resigned on July 13. Deputy Raúl Alberto Lastiri, José López Rega's son-in-law and also a P2 member, was then promoted to the presidency to organize new elections. Cámpora's supporters, like Chancellor Juan Carlos Puig and Interior Minister Esteban Righi, were immediately replaced. The Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo (ERP – People's Revolutionary Army) was declared a "dissolved terrorist organization." On September 23, Perón won the elections with 61.85% of the votes, with his third wife, Isabel Perón, as vice-president. Their government began on October 12.

Peronist right-wing groups won a clear victory, and Perón became President in October 1973, a month after Pinochet's coup in Chile. Violent acts, including by the Triple A, continued to threaten public order. On September 25, 1973, José Ignacio Rucci, the CGT trade-union's Secretary General and Perón's friend, was assassinated by the Montoneros. The government used several emergency decrees, including special executive authority to deal with violence. This allowed the government to imprison people indefinitely without charge.

In his second time in office, Perón aimed to achieve political peace by creating a new alliance between businesses and workers to rebuild the nation. Perón's charm and his past support for labor helped him keep the support of the working class.

Isabel Perón's Government (1974–1976)

Perón died on July 1, 1974. His wife, Isabel Perón, took over as president. However, her government faced many problems: the economy collapsed (inflation was very high and the economy shrank), there were internal struggles within the Peronist party, and acts of terrorism by insurgents like the ERP and paramilitary groups increased.

Isabel Perón was new to politics and mainly relied on Perón's name. López Rega was described as a man interested in occult practices, including astrology, and a supporter of certain Catholic groups. Economic policies aimed to change wages and currency values to attract foreign investment to Argentina. López Rega was removed as Isabel Perón's advisor in June 1975. General Numa Laplane, the army commander who had supported the government during the Lopez Rega period, was replaced by General Jorge Rafael Videla in August 1975.

The Montoneros, led by Mario Firmenich, carefully decided to go underground after Perón's death. Isabel Perón was removed from office by the military coup on March 24, 1976. This led to Argentina's last and arguably most violent military government, known as the National Reorganization Process.

National Reorganization Process (1976–1983)

After the coup against Isabel Perón, the armed forces officially held power through a group of leaders called a junta. This junta was led by Videla, Viola, Galtieri, and Bignone in succession, until December 10, 1983. These military leaders called their government program the "National Reorganization Process." The term "Dirty War" (Spanish: guerra sucia) is used to describe this period of state terrorism in Argentina. It was part of Operation Condor, starting in 1974. During this time, military and security forces, along with right-wing death squads like the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance (Triple A), hunted down anyone who was (or was suspected to be) a political dissident or associated with socialism or against the plan of neoliberal economic policies. About 30,000 people disappeared. Many could not be formally reported as missing because of the nature of this state terrorism.

The targets included students, activists, trade unionists, writers, journalists, artists, and anyone suspected of being a left-wing activist, including Peronist guerrillas. The "disappeared" included those thought to be a political or ideological threat to the military government, even vaguely. They were killed in an attempt by the government to silence any social and political opposition.

Serious economic problems, growing accusations of corruption, public unhappiness, and finally, Argentina's defeat by the United Kingdom in the Falklands War in 1982 (after Argentina's unsuccessful attempt to take the Falkland Islands) all worked together to discredit the Argentine military government. Under strong public pressure, the junta lifted bans on political parties and slowly brought back basic political freedoms.

Most of the members of the Junta are currently in prison for crimes against humanity and genocide.

Beagle Conflict

The Beagle conflict started in the 1960s when Argentina began to claim that the Picton, Lennox, and Nueva islands in the Beagle Channel rightfully belonged to Argentina. In 1971, Chile and Argentina signed an agreement to formally let an international court decide the Beagle Channel issue. On May 2, 1977, the court ruled that the islands and all nearby land belonged to Chile.

On January 25, 1978, the Argentine military government, led by General Jorge Videla, declared the court's decision invalid and increased their claim over the islands. On December 22, 1978, Argentina started Operation Soberanía to invade the disputed islands. However, the invasion was stopped because of military concerns. The newspaper Clarín later explained that to win, certain goals had to be reached within seven days of the attack. Some military leaders thought this wasn't enough time due to the difficulty of moving troops through the passes over the Andean Mountains.

Clarín also reported two fears: first, that the conflict could spread to other countries in the region. Second, that it could become a conflict involving major world powers. If other countries like Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Brazil intervened, then major powers might take sides. In that case, the outcome of the conflict would depend on the countries supplying weapons, not just the fighting nations.

In December of that year, just before Videla signed a declaration of war against Chile, Pope John Paul II agreed to mediate between the two nations. The Pope's representative, Cardinal Antonio Samorè, successfully prevented war. He proposed a new border where the three disputed islands would remain Chilean. Argentina and Chile both agreed to Samoré's proposal and signed the Treaty of Peace and Friendship of 1984 between Chile and Argentina, ending that dispute.

New Democracy (1983–Present)

On October 30, 1983, Argentines went to the polls to choose a president, vice-president, and national, provincial, and local officials. International observers found these elections to be fair and honest. The country returned to constitutional rule after Raúl Alfonsín, candidate of the Radical Civic Union (Unión Cívica Radical, UCR), received 52% of the popular vote for president. He began a 6-year term on December 10, 1983.

Alfonsín Era (1983–1989)

Five days after taking office, Alfonsín created the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons (CONADEP), led by Argentine writer Ernesto Sabato. This commission investigated the disappearances during military rule. However, under Alfonsín's presidency, the "Full stop law" was passed on December 24, 1986. This law granted amnesty (forgiveness) for all acts committed before December 10, 1983, due to pressure from the military. It wasn't until June 2005, when the Supreme Court overturned all amnesty laws, that investigations could start again.

During the Alfonsín government, a Treaty of Peace and Friendship of 1984 between Chile and Argentina with Chile was signed. Also, the beginnings of the Mercosur trade bloc were established.

In 1985 and 1987, many people voted in mid-term elections, showing continued public support for a strong democratic system. The UCR-led government took steps to solve some of the nation's most urgent problems. These included finding out what happened to those who disappeared during military rule, establishing civilian control of the armed forces, and strengthening democratic institutions. One of the biggest achievements of the Alfonsín government was reducing corruption in public offices by half.

However, constant disagreements with the military, failure to solve several economic problems inherited from the military dictatorship, and strong opposition from labor unions weakened the Alfonsín government. He left office six months early after Peronist candidate Carlos Menem won the 1989 presidential elections.

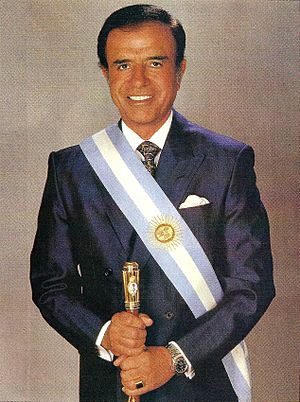

Menem's Decade (1989–1999)

As President, Carlos Menem made big changes to Argentina's domestic policy. Large-scale structural reforms dramatically changed the government's role in Argentina's economy. It was ironic that Menem, a Peronist, oversaw the privatization of many industries that Perón had previously nationalized.

Menem was a decisive leader and wasn't afraid to use the president's powers to issue "emergency" decrees (officially Necessity and Urgency Decrees) when Congress couldn't agree on his proposed reforms. Those powers were somewhat limited when the constitution was changed in 1994. This change was a result of the Pact of Olivos with the opposition Radical Party. That agreement allowed Menem to seek and win re-election with 50% of the vote in the three-way 1995 presidential race. The Piquetero movement, a group of unemployed workers who protested by blocking roads, also emerged during this time.

The 1995 election saw the rise of the moderate-left FrePaSo political alliance. This alternative to Argentina's two traditional political parties was especially strong in Buenos Aires but lacked the national organization of the Peronists and Radicals. In an important development in Argentina's political life, all three major parties in the 1999 election supported free market economic policies.

New Millennium Crisis (1999–2003)

De La Rúa's Presidency (1999–2001)

In October 1999, the UCR–FrePaSo Alianza's presidential candidate, Fernando de la Rúa, defeated Peronist candidate Eduardo Duhalde. De la Rúa took office in December 1999. He followed a program supported by the IMF that involved cutting government spending, increasing revenue, and reforming how money was shared with provinces to control the federal fiscal deficit. He also pursued labor market flexibility and business-promotion measures to attract foreign investment, hoping to avoid defaulting on the public debt.

Towards the end of 2001, Argentina faced serious economic problems. The IMF pressured Argentina to pay its external debt, which effectively forced Argentina to devalue the Argentine peso. The peso had been fixed to the U.S. dollar. Deep budget cuts, including a 13% reduction in pay for the nation's 2 million public sector employees, failed to stop the rapidly increasing risk on almost U$100 billion in Argentine bonds. This increased debt service costs and further limited access to international credit, despite a somewhat successful debt swap arranged by Minister Cavallo with most bondholders. Voters reacted to the rapidly worsening economy in the October 2001 midterm elections by both taking away the Alliance's majority in the Lower House and casting a record 25% of spoiled ballots.

Corralito (2001)

On November 1, 2001, people feared the peso would be devalued, causing massive withdrawals of bank deposits and capital flight (money leaving the country). De la Rúa's Minister of Economy Domingo Cavallo passed rules severely limiting withdrawals, effectively freezing the peso-denominated money of the Argentine middle class. However, dollar-denominated foreign accounts were protected from devaluation. This freezing of bank accounts was informally called corralito.

The overall economy declined sharply during December 2001. The resulting riots led to dozens of deaths. The Minister of Economy Domingo Cavallo resigned, but that didn't stop the collapse of De la Rúa's government. On December 20, De la Rúa also resigned. The political crisis was extremely serious because the vice-president Carlos "Chacho" Álvarez had already resigned in 2000. The president of the Senate became interim president until the National Congress elected Adolfo Rodríguez Saá two days later to finish De la Rúa's term. But Rodríguez Saá resigned a week later on December 31, leaving power to the interim president of the Chamber of Deputies.

Finally, on January 2, 2002, the National Congress elected the Peronist Eduardo Duhalde, who had lost the most recent presidential election, as president. The peso was first devalued by 29%, and then its fixed rate to the dollar was abandoned. By July 2002, the national currency had depreciated to one-quarter of its former value.

Recovery (2002–2003)

President Duhalde faced a country in chaos. His government had to deal with many protests (middle-class cacerolazos and unemployed piqueteros). He handled them with a relatively tolerant policy, aiming to minimize violence. As inflation became a serious issue and the effects of the crisis became clear with increased unemployment and poverty, Duhalde chose a moderate, quiet economist, Roberto Lavagna, as his Minister of Economy. The economic measures put in place brought inflation under control.

After a year, Duhalde felt he had completed his tasks. Under pressure from certain political groups, he called for elections. In April 2003, Néstor Kirchner, the center-left Peronist governor of Santa Cruz, came to power.

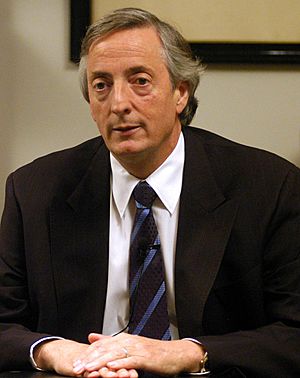

Kirchner Governments (2003–2015)

President Néstor Kirchner took office on May 25, 2003. He reorganized the leadership of the Armed Forces. He also overturned controversial amnesty laws that protected members of the 1976–1983 dictatorship from being prosecuted. He kept Lavagna as economy minister for most of his presidency. Kirchner's government saw a strong economic recovery and a restructuring of foreign debt.

The Guardian newspaper compared Kirchner's economic policy to that of Franklin Roosevelt during the Great Depression. The Argentine president managed to revive a failing economy (with 21% unemployment, half the population below the poverty line, and a 20% drop in GDP). He did this by rejecting IMF demands. This economic policy allowed Argentina to grow by an average of 8% per year and lifted 11 million people out of poverty.

On October 28, 2007, the 2007 general election took place in ten provinces. Cristina Fernández de Kirchner's Front for Victory won in six provinces. Hermes Binner was elected Governor of Santa Fe, becoming the first Socialist governor in Argentina's history and the first non-Peronist to rule the wealthy Santa Fe province. Center-left Fabiana Ríos of ARI became the first woman to be elected governor of Tierra del Fuego. Meanwhile, center-right Mauricio Macri was elected Chief of Government of Buenos Aires City in June 2007.

On December 10, 2007, then-First Lady and Senator Cristina Fernández de Kirchner took over the presidency from her husband, after winning elections with 44% of the vote. Her husband remained a very influential politician during her term. The press used the term "presidential marriage" to refer to both of them at once. Some political analysts compared this type of government to a diarchy (rule by two people).

After proposing a new tax system for agricultural exports, Fernández de Kirchner's government faced a severe lockout by the farming sector. The protest, which lasted over 129 days, quickly became political and marked a turning point in her administration. The new tax system was finally rejected in the Senate by a vote against it from Vice President Julio Cobos.

The government's political style changed in 2010 with the death of Néstor Kirchner. President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner slowly moved away from the traditional structure of the Justicialist Party and instead favored La Cámpora, a group of young supporters led by her eldest son Máximo Kirchner.

In the elections of 2011, President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner of the Front for Victory won by a large margin, with 54.11% of the votes, against Hermes Binner. She won in Buenos Aires City and every province except San Luis (won by Federal Commitment candidate Alberto Rodríguez Saá). She became the first candidate to get an absolute majority of the popular vote since Raúl Alfonsín in 1983. Her margin of victory (37.1%) even exceeded Juan Perón's record 36% margin in 1973. Fernández de Kirchner became the first woman re-elected as head of state in Latin American history.

Macri Administration (2015–2019)

On November 22, 2015, Buenos Aires Mayor Mauricio Macri won the presidency in a run-off election, succeeding Cristina Fernández de Kirchner as president. As leader of the Republican Proposal (PRO) party, he won the presidency with an alliance called Cambiemos (Let's Change). This alliance also included the Civic Coalition ARI and the Radical Civic Union. He defeated the former Buenos Aires Province Governor Daniel Scioli of Front for Victory. Macri took over as president on December 10 of that same year. His government changed direction from the previous era, moving back to neoliberal policies.

He was one of the political leaders mentioned in the Panama Papers scandal, where he was identified as having several offshore companies. Other leaders have used such companies to avoid taxes, though he has not faced any convictions for this.

Fernández Administration (2019–Present)

On December 10, 2019, the Centre-Left Alberto Fernández of the Justicialist Party became President. He defeated the previous president, Mauricio Macri, in the 2019 Argentine general election.

On November 14, 2021, Argentina's ruling Peronist party's center-left coalition, Frente de Todos (Front for Everyone), lost its majority in Congress. This was the first time in almost 40 years that this happened in midterm legislative elections. The election victory of the center-right coalition, Juntos por el Cambio (Together for Change), meant a tough final two years in office for President Alberto Fernandez. Losing control of the Senate made it difficult for him to make key appointments, including to the judiciary. It also forced him to negotiate with the opposition on every new law he sent to the legislature.

In April 2023, President Alberto Fernandez announced that he would not seek re-election in the next presidential election.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la Argentina para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la Argentina para niños

- Economic history of Argentina

- Afro-Argentines

- Historiography of Argentina

- History of Argentine nationality

- List of presidents of Argentina

- History of folkloric music in Argentina

- Politics of Argentina

- State-Church relations in Argentina

- ¿Qué hubiera pasado si...? (book)

General:

- History of Latin America

- History of South America

- Latin America–United Kingdom relations

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |