Nine Years' War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Nine Years' War |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Anglo-French Wars and the French–Habsburg rivalry | |||||||||

Left to right:

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Grand Alliance: | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 680,000 military deaths | |||||||||

The Nine Years' War (1688–1697) was a big conflict between France and a group of countries called the Grand Alliance. This group included the Holy Roman Empire, the Dutch Republic, England, Spain, and Savoy. Even though most of the fighting happened in Europe, it also spread to places like the Americas, India, and West Africa. Some people even call it the first ever world war. Other smaller conflicts, like the Williamite war in Ireland and King William's War in North America, were part of this larger war.

Louis XIV of France, the King of France, was the most powerful ruler in Europe after the Franco-Dutch War ended in 1678. He wanted to make France even stronger by adding more land to its borders. He used a mix of force and legal tricks to do this. This led to a smaller conflict called the War of the Reunions from 1683 to 1684. A peace agreement, the Truce of Ratisbon, was supposed to keep these new borders for twenty years. However, other European countries were worried about France growing too powerful and about Louis XIV's harsh policies against Protestants. This led to the creation of the Grand Alliance, led by William of Orange.

In September 1688, Louis XIV decided to send his army across the Rhine River. He hoped this would make the Holy Roman Empire accept his claims to new territories. But instead, Emperor Leopold I and other German leaders joined the Dutch to oppose France. Also, in November 1688, a big event called the Glorious Revolution happened in England. This brought William of Orange to the English throne and added England's power to the Alliance. For the next few years, battles mainly took place in the Spanish Netherlands, the Rhineland, the Duchy of Savoy, and Catalonia. At first, France seemed to have the upper hand. But by 1696, neither side could win a clear victory, and everyone was running out of money. This made them eager to talk about peace.

The war ended with the Peace of Ryswick in 1697. France kept Alsace but gave Lorraine back to its ruler. France also returned some lands on the right side of the Rhine River. Louis XIV finally recognized William III as the rightful King of England. The Dutch also gained control of some important forts in the Spanish Netherlands to protect their borders. However, both sides knew this peace might not last. It didn't solve the big question of who would become the next ruler of the Spanish Empire after the sick and childless Charles II of Spain died. This question had been a major problem in Europe for over 30 years and would lead to another war, the War of the Spanish Succession, in 1701.

Contents

Why the War Started: 1678–1687

After the Franco-Dutch War (1672–78), King Louis XIV of France was very powerful. He wanted to unite France under one religion and make its borders stronger. He wasn't looking for huge new conquests like before. Instead, he used France's strong army to get specific lands along his borders. Louis, known as the "Sun King," had learned that simply fighting wars wasn't always the best way. He started using threats to make his neighbors agree to his demands.

Louis XIV, along with his top military and foreign advisors, wanted to build a strong defense system for France. His expert, Vauban, suggested building many strong forts along the border to keep enemies out. To do this, France needed to take more land from its neighbors to create a clear and defensible border. This meant that even though Louis's main goal was defense, he used aggressive methods to get the land he wanted. This strategy was called the "Reunions."

The Reunions: France Expands its Borders

The peace treaties signed in 1678 (Treaties of Nijmegen) and 1648 (Peace of Westphalia) gave Louis XIV a reason for the Reunions. These treaties gave France some land, but their wording was often unclear about exact borders. This led to arguments over areas where France gained a town and its "dependencies," but nobody was sure what those dependencies included. Special courts were set up to decide these unclear border issues. Not surprisingly, these courts usually decided in Louis XIV's favor.

By 1680, France had taken control of the County of Montbéliard and, by August, almost all of Alsace, except for Strasbourg. The court in Metz also claimed land around the Three Bishoprics (Metz, Toul, and Verdun) and most of the Spanish Duchy of Luxembourg. The important fortress of Luxembourg City was then surrounded by French troops.

On September 30, 1681, French soldiers also took Strasbourg and its outpost, Kehl, on the other side of the Rhine River. This bridge had often been used by enemy troops. By taking Strasbourg, France now controlled two out of three main bridges over the Rhine. On the same day, French forces marched into Casale in northern Italy. This fortress was bought from the Duke of Mantua. Along with another French fort, Pinerolo, this allowed France to control the Duke of Savoy and threaten the Spanish Duchy of Milan. All these newly claimed lands were important entry and exit points between France and its neighbors. Vauban immediately fortified them as part of France's defense system.

By trying to build an unbeatable border, Louis XIV made other European countries very worried. This made a general war, which he wanted to avoid, seem unavoidable. His forts protected France but also showed off French power. Only two leaders seemed strong enough to stand against Louis XIV: William of Orange, the leader of the Dutch Republic and a strong Protestant voice, and Leopold I, the leader of the Holy Roman Empire and Catholic Europe. Both wanted to act, but they couldn't immediately because the Dutch didn't want more conflict, and Spain and the Empire were weak. Many German princes were also still being paid by France.

Fighting on Two Fronts: East and West

Louis XIV saw Emperor Leopold I as his most dangerous enemy. However, Leopold I was busy fighting the Ottoman Turks on his Hungarian borders, who were threatening to take over Central Europe. Louis actually encouraged the Ottomans and promised not to help the Emperor. He even tried to convince the King of Poland not to help Leopold I. When the Ottomans surrounded Vienna in 1683, Louis did nothing to help.

Taking advantage of the Ottoman threat, Louis invaded the Spanish Netherlands on September 1, 1683. He restarted the siege of Luxembourg. France demanded that the Emperor and Charles II of Spain accept the new lands France had taken. But Spain didn't want to lose any more territory. Spain's army was weak, but the Ottomans' defeat at Vienna on September 12 gave them courage. Hoping Leopold I would make peace in the east and help him, Charles II declared war on France on October 26. However, the Emperor decided to keep fighting the Turks in the Balkans and make a deal in the west for now. With Leopold I unwilling to fight on two fronts, and William of Orange unable to act due to pro-French feelings in Amsterdam, France seemed set for a complete victory.

The War of the Reunions was short and destructive. After France captured Courtrai in November, Dixmude in December, and Luxembourg in June 1684, Charles II had to accept Louis XIV's peace terms. The Truce of Ratisbon, signed on August 15, gave France Strasbourg, Luxembourg, and the lands taken in the Reunions (Courtrai and Dixmude were returned to Spain). This was not a lasting peace, but a truce for 20 years. Louis was happy because the Emperor and German princes were busy in Hungary, and William of Orange was isolated in the Dutch Republic.

Persecution of Protestants and Growing Opposition

After 1685, France's strong position began to weaken. A major reason was Louis XIV's decision to cancel the Edict of Nantes. This law had protected Protestants in France. When it was canceled, many Huguenots (French Protestants) fled to England, the Dutch Republic, Switzerland, and Germany. They told stories of harsh treatment by Louis XIV's government. This greatly weakened the pro-French group in the Dutch Republic and hurt trade between France and the Netherlands.

The persecution also made the Dutch more suspicious of James II, who was the Catholic King of England. Many in the Netherlands thought James II was too close to his cousin Louis XIV. This led to more tension between Louis and William of Orange. Louis's constant demands for new land, along with his persecution of Protestants, helped William of Orange gain power in the Dutch Republic. This finally allowed him to build the alliance against France that he had wanted for a long time.

Even though James II allowed Huguenots to settle in England, he had a friendly relationship with Louis XIV. James needed Louis's support for his own plans to bring back Catholicism in England, which many Protestants opposed. However, the Huguenots' presence in England fueled anti-French feelings and made people more suspicious of James. Also, French and English traders were clashing in North America, especially over the Hudson's Bay Company and New England colonies. This rivalry even spread to Asia, where English and French trading companies were already fighting.

Many in Germany were also upset by the persecution of the Huguenots. Protestant German princes realized that Louis XIV was not their ally against the Catholic Habsburgs. The Elector of Brandenburg responded by inviting fleeing Huguenots to his lands. Other German princes also had reasons to turn against France. Louis XIV had claims to the Electoral Palatinate and threatened to take more land in the Rhineland. So, Frederick-William ended his alliance with France and made agreements with William of Orange, the Emperor, and the King of Sweden.

The flight of Huguenots from southern France even caused fighting in the Alpine region of Piedmont in the Duchy of Savoy. From their fort at Pinerolo, the French pressured the Duke of Savoy to persecute his own Protestant community, the Vaudois. The Duke, Victor Amadeus, was worried about France constantly interfering in his country. By 1687, he started to become anti-French, looking for a chance to stand up for his independence.

Criticism of Louis XIV's rule spread across Europe. The Truce of Ratisbon and the cancellation of the Edict of Nantes made people doubt Louis's true intentions. Many also feared that the King wanted to create a "universal monarchy," uniting the Spanish, German, and French crowns. In response, representatives from the Emperor, southern German princes, Spain, and Sweden formed a defensive alliance called the League of Augsburg in July 1686. Even Pope Innocent XI, who was angry at Louis for not fighting the Turks, secretly supported this alliance.

The Start of the War: 1687–1688

The League of Augsburg didn't have much military power at first. The Emperor and his allies were still busy fighting the Ottoman Turks in Hungary. Many smaller princes were afraid to act against France. However, Louis XIV watched with concern as Emperor Leopold I gained victories against the Ottomans in Hungary. French leaders believed that the Emperor, allied with Spain and William of Orange, would soon turn his attention to France to take back the lands Louis had gained.

To prevent this, Louis XIV wanted to make his land gains from the Reunions permanent. He demanded that the Truce of Ratisbon become a lasting agreement. But the Emperor, confident from his victories in the east, refused.

Another problem was the succession in the Electorate of Cologne. The Archbishop-Elector, who was pro-French, died. Louis XIV wanted his candidate, Wilhelm Egon von Fürstenberg, to take his place. But the Emperor supported Joseph Clement, the brother of Max Emanuel, the Elector of Bavaria. Since neither candidate got enough votes, the decision went to the Pope. The Pope, who was already in conflict with Louis, chose Clement.

On September 6, Leopold I's forces captured Belgrade from the Ottomans. With the Ottomans seemingly about to collapse, Louis XIV's advisors felt it was important to quickly settle things on the German border. They feared the Emperor would then turn his full attention to France. So, on September 24, Louis published a statement listing his complaints. He demanded that the Truce of Ratisbon become permanent and that Fürstenburg be made Archbishop-Elector of Cologne. He also wanted to occupy lands he believed belonged to his sister-in-law in the Palatinate. The Emperor, German princes, the Pope, and William of Orange refused these demands. For the Dutch, French control of Cologne and Liège was unacceptable because it would bypass their buffer zone with the Spanish Netherlands.

The day after Louis issued his demands, the main French army crossed the Rhine River. This was a move to attack Philippsburg, a key fort between Luxembourg and Strasbourg. This surprise attack was meant to scare the German states into accepting his terms and encourage the Ottoman Turks to keep fighting the Emperor.

Louis XIV and his advisors hoped for a quick victory, like in the War of the Reunions. But by 1688, things were very different. In the east, the Imperial army had defeated the Turks. In the west, William of Orange was leading a group of Protestant states ready to join the Emperor and Spain against France. Louis wanted a short, defensive war, but by crossing the Rhine, he started a long war that would wear everyone down. This war was about state interests, defensible borders, and the balance of power in Europe.

Nine Years of Conflict: 1688–1697

Battles in the Rhineland and Germany

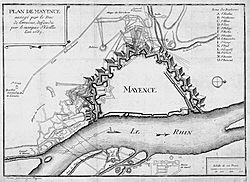

On September 27, 1688, French forces, led by Marshal Duras and Vauban, surrounded the fortress of Philippsburg. After a strong defense, it fell on October 30. The French army then took Mannheim on November 11, and Frankenthal soon after. Other towns like Oppenheim, Worms, Bingen, Kaiserslautern, Heidelberg, Speyer, and the important fortress of Mainz fell without a fight. The French also heavily attacked Coblenz, but it did not surrender.

Louis XIV now controlled the Rhine River from Mainz south to the Swiss border. However, these attacks, while keeping the Turks fighting in the east, had the opposite effect on Leopold I and the German states. The League of Augsburg wasn't strong enough to stop the threat. But on October 22, 1688, powerful German princes, including the Elector of Brandenburg and others, agreed to mobilize their forces. Meanwhile, the Emperor called back his troops from the Ottoman front to defend southern Germany.

The French had not planned for such a strong reaction. Realizing the war in Germany wouldn't end quickly, Louis XIV decided on a "scorched earth" policy in the Palatinate, Baden, and Württemberg. This meant destroying everything to prevent enemy troops from using local resources and invading French territory. By December 20, Louis's advisor Louvois had chosen all the cities, towns, and castles to be destroyed. On March 2, 1689, Heidelberg was burned. Mannheim was leveled on March 8. Oppenheim and Worms were destroyed on May 31, followed by Speyer on June 1, and Bingen on June 4. In total, French troops burned over 20 large towns and many villages and castles.

The Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire declared war on France on February 11, 1689. The Germans prepared to take back what they had lost. In 1689, they formed three armies along the Rhine. The largest army, led by Charles V, Duke of Lorraine, took back Mainz after a two-month siege. On the lower Rhine, the Elector of Brandenburg, with help from the Dutch engineer Menno van Coehoorn, besieged Kaiserswerth, which fell on June 26. He then led his army to Bonn, which surrendered on October 10 after heavy bombing. The French invasion of the Rhineland had united the German princes against Louis XIV, who had lost more than he gained that year. This campaign also distracted French forces, giving William of Orange enough time to invade England.

England's Glorious Revolution

King James II's attempts to make the army, government, and other parts of society more Catholic were very unpopular with his mostly Protestant subjects. His open Catholicism and his dealings with Catholic France also strained relations between England and the Dutch Republic. However, because his daughter Mary was the Protestant heir to the English throne, her husband, William of Orange, was careful not to act against James II, fearing it would harm her chances of becoming queen.

But if England was left alone, the situation could become very bad for the Dutch Republic. Louis XIV might step in and make James II his puppet. Or James, wanting to distract his subjects, might even join Louis in attacking the Dutch Republic, like in 1672. By late 1687, William started planning to intervene. By early 1688, he secretly began making preparations. The birth of a son to James's second wife in June meant William's wife Mary was no longer the direct heir. With the French busy in the Palatinate, the Dutch government fully supported William. They knew that overthrowing James II was important for their own country's safety.

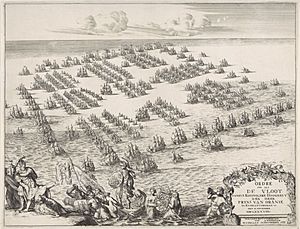

William's invasion fleet was huge: 463 ships and 40,000 men, about twice the size of the Spanish Armada from 1588. It included 49 warships, 76 transport ships for soldiers, and 120 for the 5,000 horses needed for cavalry and supplies. For show, English Admiral Arthur Herbert was put in charge, but the real control was with Dutch admirals.

Louis XIV saw William's invasion as a declaration of war between France and the Dutch Republic. But he did little to stop it because his main concern was the Rhineland. French diplomats thought William's actions would cause a long civil war in England, which would either use up Dutch resources or bring England closer to France. However, after William's forces landed easily at Torbay on November 5, many welcomed him. The Glorious Revolution quickly ended James II's rule. On February 13, 1689, William of Orange became King William III of England, ruling jointly with his wife Mary. This linked the futures of England and the Dutch Republic.

Few in England realized that William wanted the crown for himself or that his goal was to bring England into the war against France on the Dutch side. Parliament didn't immediately see that offering the joint monarchy meant declaring war. But the actions of the deposed king finally made Parliament support William's war policy.

Historian J. R. Jones says that King William was given

supreme command within the alliance throughout the Nine Years' War. His experience and knowledge of European affairs made him the indispensable director of Allied diplomatic and military strategy, and he derived additional authority from his enhanced status as king of England – even the Emperor Leopold ... recognized his leadership. William's English subjects played subordinate or even minor roles in diplomatic and military affairs, having a major share only in the direction of the war at sea. Parliament and the nation had to provide money, men and ships, and William had found it expedient to explain his intentions ... but this did not mean that Parliament or even ministers assisted in the formulation of policy.

Before British forces could join the war effectively, the English army needed to be reorganized. James's commander had disbanded the army in December 1688, so it had to be rebuilt from scratch. Dutch officers were put in key positions to reform the English army and train troops in new methods. To make this easier for the British, the Dutch agreed that an Englishman would always command a combined Anglo-Dutch fleet.

Fighting in Ireland and Scotland

After fleeing England in December 1688, James II found safety with Louis XIV, who gave him money and support. On March 12, 1689, James landed in Ireland with 6,000 French troops. He was supported by most of the Catholic population there. His supporters were called "Jacobites." The war in Ireland was also connected to a rebellion in Scotland. James's main goal was to retake England, so he saw Scotland and Ireland as less important. Louis, however, saw them as a way to distract British resources from the main fighting in Europe. This difference in goals was never fully resolved.

James's Catholic deputy in Ireland had gathered an army of about 36,000 men. However, many were poorly equipped, and it was hard to feed and supply them. Although they quickly took over much of Ireland, they couldn't capture the important northern port of Derry and had to retreat in July. In August, Williamite general Schomberg landed with 15,000 more troops. But problems with supplies meant his army got stuck and suffered many illnesses and desertions.

The Scottish Jacobites won a battle at Killiecrankie in July 1689 but suffered heavy losses, including their leader. By May 1690, the rebellion in Scotland was mostly put down, though some resistance continued until early 1692. At the same time, William III took command of government troops in Ireland and won an important victory at The Battle of the Boyne in July 1690. After this, a French naval victory gave them temporary control of the English Channel. James returned to France, urging an immediate invasion of England. But the Anglo-Dutch fleet soon regained control of the seas, and the chance was lost.

By the end of 1690, French and Jacobite troops were limited to southern and western Ireland. William transferred command to Godert de Ginkel and returned to Flanders. Even with more troops and a new general, the Franco-Irish army was defeated at Aughrim on July 12, 1691. The war in Ireland ended with the Treaty of Limerick in October, allowing most of William's forces to be sent to Europe.

Goals of the Grand Alliance

William's successful invasion of England quickly led to the alliance he had wanted for so long. On May 12, 1689, the Dutch and the Holy Roman Emperor signed an agreement in Vienna. Their goal was to force France back to its borders as they were in 1659, taking away all the land Louis XIV had gained since he became king. For the Emperor and German princes, this meant getting back Lorraine, Strasbourg, parts of Alsace, and some forts in the Rhineland. Leopold I had tried to finish the war with the Turks to focus on France. But the French invasion of the Rhineland encouraged the Turks to demand harsher peace terms, which the Emperor couldn't accept. So, Leopold I decided to fight France in the west while still fighting the Ottomans in the Balkans.

William III saw the war as a chance to reduce France's power and protect the Dutch Republic. He also wanted to create conditions that would help trade. While there were still some border issues, the Dutch didn't aim for big changes to their borders. William's main goal was to secure his new position as King of Britain. By seeking refuge in France and then invading Ireland, James II gave William III the perfect reason to convince the English Parliament that joining a major European war was necessary. With Parliament's support, William III and Mary II declared war on May 17. They then passed a law that stopped all English trade with France.

This alliance between England and the Dutch was the foundation for the Grand Alliance, officially agreed upon on December 20. Like the Dutch, the English weren't focused on gaining land in Europe. Instead, they were very concerned with limiting France's power and preventing James II from returning to the throne. William III had achieved his goal of getting Britain's resources for the anti-French alliance. However, the Jacobite threat in Scotland and Ireland meant that only a small English army could be sent to help the Dutch in the Spanish Netherlands for the first three years of the war.

The Duke of Lorraine also joined the Alliance at the same time as England. The King of Spain, who had been at war with France since April, and the Duke of Savoy signed up in June 1690. The Allies offered Victor Amadeus, the Duke of Savoy, good terms to join them. These included getting back Casale and Pinerolo. His joining would allow the Allies to invade France through Dauphiné and Provence, where the important naval base of Toulon was located. In contrast, Louis XIV had tried to keep Savoy on France's side by threatening military action. French demands on Victor Amadeus convinced the Duke that he had to stand up to French aggression.

The Elector of Bavaria joined the Grand Alliance on May 4, 1690, and the Elector of Brandenburg joined on September 6. However, not all the smaller powers were fully committed to the cause, and they all protected their own interests. Some demanded a high price for their continued support. Sweden provided troops and warships from its German lands. Denmark agreed to supply 7,000 troops to William III in exchange for money. However, in March 1691, Sweden and Denmark put aside their differences and agreed to stay neutral to protect their trade and prevent the war from spreading north. To the annoyance of England and the Dutch, Sweden saw its role outside the main war, using the chance to increase its own sea trade. Nevertheless, Louis XIV finally faced a powerful group of countries determined to make France respect Europe's rights and interests.

Expanding the War: 1690–1691

Most of the fighting in the Nine Years' War happened around France's borders: in the Spanish Netherlands, the Rhineland, Catalonia, and Piedmont-Savoy. The Spanish Netherlands was important because it was located between France and the Dutch Republic. At first, French forces there were commanded by Marshal Humières. In 1689, while the French focused on the Rhine, there wasn't much action. The most important event was when William's second-in-command, the Prince of Waldeck, defeated Humières at the Battle of Walcourt on August 25.

However, by 1690, the Spanish Netherlands became the main battleground. The French had two armies there: one under Boufflers on the Moselle River, and a larger one to the west under Marshal Luxembourg, who was Louis XIV's greatest general at the time. On July 1, Luxembourg won a clear victory over Waldeck at the Battle of Fleurus. But this success didn't lead to much. Louis XIV was more concerned about his son, the Dauphin, on the Rhine, which stopped a plan to besiege Namur or Charleroi. For the Emperor and German princes, the most serious event of 1690 was that the Turks had won battles on the Danube, forcing them to send more troops to the east. The Elector of Bavaria, now the Imperial commander, couldn't do much on the Rhine, and the campaign there didn't have any major battles or sieges.

The smallest front of the war was in Catalonia. In 1689, the Duke of Noailles led French forces there. He aimed to put more pressure on Spain by restarting a peasant uprising against Charles II, which had begun in 1687. Noailles captured Camprodon on May 22, but a larger Spanish army forced him to retreat in August. The Catalan campaign quieted down in 1690, but a new front in Piedmont-Savoy became more active. This area saw a lot of religious hatred and Savoyard dislike for the French, leading to massacres and terrible acts. Constant guerrilla attacks by local people were met with harsh punishments. In 1690, Saint-Ruth took most of Victor Amadeus II's exposed Duchy of Savoy, defeating the Savoyard army until only the large fortress of Montmélian remained. To the south in Piedmont, Nicolas Catinat led 12,000 men and soundly defeated Victor Amadeus at the Battle of Staffarda on August 18. Catinat immediately took several towns but had to retreat across the Alps for the winter due to a lack of troops and widespread sickness.

French successes in 1690 had stopped the Allies on most land fronts, but they hadn't broken the Grand Alliance. Hoping to weaken the alliance, French commanders in 1691 planned two early attacks: capturing Mons in the Spanish Netherlands and Nice in northern Italy. Boufflers surrounded Mons on March 15 with about 46,000 men, while Luxembourg commanded a similar force to watch. After some of the most intense fighting of Louis XIV's wars, the town surrendered on April 8. Luxembourg then took Halle in late May, and Boufflers bombed Liège. But these actions had no major political or strategic impact. The last important action in the Low Countries happened on September 19, when Luxembourg's cavalry surprised and defeated the rear of the Allied forces in a small battle near Leuze. Now that the defense of the Spanish Netherlands depended almost entirely on the Allies, William III insisted on replacing its Spanish governor with the Elector of Bavaria, which helped speed up decisions.

In 1691, there was little major fighting on the Catalan and Rhineland fronts. In contrast, the northern Italian area was very active. Villefranche fell to French forces on March 20, followed by Nice on April 1. This stopped any Allied invasion of France along the coast. Meanwhile, to the north in the Duchy of Savoy, the Marquis of La Hoguette took Montmélian (the last remaining stronghold in the region) on December 22, a big loss for the Grand Alliance. However, the French campaign on the Piedmontese plain was not successful. Although Carmagnola fell in June, the French commander, Marquis of Feuquières, quickly abandoned the Siege of Cuneo when he heard Prince Eugene of Savoy's relief force was coming. He lost about 800 men and all his heavy guns. With Louis XIV focusing his resources in Alsace and the Low Countries, Catinat had to play defense. The Allies now had the advantage in northern Italy. By August, they had 45,000 men in the region, allowing them to retake Carmagnola in October. Louis XIV offered peace terms in December, but Amadeus, expecting to have a military advantage in the next campaign, wasn't ready to negotiate seriously.

Intense Fighting: 1692–1693

After the sudden death of the important Louvois in July 1691, Louis XIV took a more active role in military decisions. He relied on advice from experts like Vauban. Louvois's death also changed state policy, with less adventurous ministers joining Louis XIV's government. From 1691 onwards, Louis XIV tried to break up the Grand Alliance through secret talks with Emperor Leopold I and, from August, attempts to find common ground with Catholic Spain. The talks with Spain failed because the Nine Years' War was not a religious war. But England and the Dutch Republic also wanted peace. Talks were difficult because Louis XIV didn't want to give up his earlier gains and wouldn't recognize William III as the rightful King of England. William III, for his part, was very suspicious of Louis XIV and his plans for a "universal monarchy."

In the winter of 1691-92, the French planned a big attack to gain an advantage over their enemies. They planned to invade England to support James II and simultaneously attack Namur in the Spanish Netherlands. The French hoped that taking Namur would make the Dutch want peace. Even if not, capturing it would be an important bargaining chip in future peace talks. With 60,000 men, protected by a similar force under Luxembourg, Marshal Vauban surrounded Namur on May 29. The town quickly fell, but the citadel, defended by van Coehoorn, held out until June 30. To improve the situation in the Spanish Netherlands, William III surprised Luxembourg's army near the village of Steenkirk on August 3. The Allies had some early success, but as French reinforcements arrived, William III's advance stopped. Both sides claimed victory: the French because they stopped the attack, and the Allies because they saved Liège from the same fate as Namur. However, due to the way wars were fought back then, the battle, like Fleurus before it, didn't change much.

While the French succeeded at Namur, the planned invasion of England failed. James II believed he would get a lot of support once he landed in England. But delays and confusing orders led to a very uneven naval battle in the English Channel. The battle lasted six days. On May 29, the French fleet of 44 ships fought bravely against 82 English and Dutch ships. However, the French were forced to retreat. Some escaped, but 15 ships that sought safety were destroyed by English sailors and fireships on June 2-3. With the Allies now in control of the English Channel, James II's invasion was abandoned. The battle itself wasn't the end for the French navy. Later mismanagement and lack of funding, along with Louis XIV's own lack of interest, were the main reasons France lost naval superiority to England and the Dutch during the Nine Years' War.

Meanwhile, in southern Europe, the Duke of Savoy, with 29,000 men, invaded Dauphiné. The Allies captured Embrun on August 15, before looting the deserted town of Gap. However, their commander fell ill with smallpox, and they decided holding Embrun was impossible. The Allies left Dauphiné in mid-September, leaving behind 70 burned and looted villages and castles. The attack on Dauphiné forced Noailles to send troops to help Catinat, leaving him with a quiet campaign in Catalonia. But on the Rhine, the French gained the upper hand. The French commander focused on collecting taxes in Swabia and Franconia. In October, he ended the siege of Ebernburg before returning to winter quarters.

By 1693, the French army had grown to over 400,000 men. But Louis XIV was facing a financial crisis. France and northern Italy suffered severe crop failures, leading to widespread famine that killed an estimated two million people by the end of 1694. Despite this, Louis XIV planned to go on the offensive before offering peace terms to the Grand Alliance. Luxembourg would campaign in Flanders, Catinat in northern Italy, and Marshal de Lorge would attack Heidelberg in Germany, where Louis XIV hoped for a war-winning advantage. Heidelberg fell on May 22 before Luxembourg's army even took the field in the Netherlands. But the new Imperial commander on the Rhine, Prince Louis of Baden, put up a strong defense and stopped further French gains.

In the Low Countries, the French took Huy. On July 23, Luxembourg found William's army near Neerwinden and Landen. The battle on July 29 was close and costly, but French forces, whose cavalry again showed their strength, won. However, William was able to quickly replace his losses, while Luxembourg's infantry was so damaged that he couldn't besiege Liège, which had been the main French goal that year. To still get something from the campaign, Louis ordered Luxembourg and Vauban to take Charleroi, the last Spanish stronghold. The French captured the town on October 10. This, along with Mons, Namur, and Huy, gave the French a new and strong line of defense.

In northern Italy, Catinat marched on Rivoli (with reinforcements from the Rhine and Catalan fronts). This forced the Duke of Savoy to stop besieging Pinerolo and retreat to protect his rear. The resulting Battle of Marsaglia on October 4, 1693, was a big French victory. Turin was now open to attack, but more problems with manpower and supplies stopped Catinat from taking advantage of his win. All the French got from their victory was a chance to restock what was left of Pinerolo. Elsewhere, Noailles captured the important seaport of Rosas in Catalonia on June 9 before retreating. When his opponent abandoned plans to besiege Bellver, both sides went into winter quarters. Meanwhile, the French navy won its last major fleet battle of the war. On June 27, Tourville's squadrons ambushed the Smyrna convoy (a fleet of 200 to 400 Allied merchant ships) as it sailed around Cape St. Vincent. The Allies lost about 90 merchant ships worth a lot of money.

War and Diplomacy: 1694–1695

French victories at Heidelberg, Rosas, Huy, Landen, Charleroi, and Marsaglia were impressive. But with the severe economic problems of 1693 continuing into 1694, France couldn't spend as much money or energy on the next campaigns. This crisis changed French strategy, forcing commanders to adjust their plans to fit the financial shortages. Behind the scenes, Louis XIV's agents worked hard to break up the Grand Alliance. But the Emperor, who had secured his claims to the Spanish throne if Charles II died during the conflict, didn't want a peace that wouldn't benefit him. The Grand Alliance would stay together as long as they had money and believed their armies would soon be much stronger than France's.

In the Spanish Netherlands, Luxembourg still had 100,000 men, but he was outnumbered. Without enough supplies to attack, Luxembourg couldn't stop the Allies from putting troops in Dixmude. On September 27, 1694, the Allies recaptured Huy, which was important for future operations against Namur. Elsewhere, the French commander on the Rhine moved his troops around with little result before the campaign ended in October. In Italy, ongoing French financial problems and a complete breakdown in supplies stopped Catinat's push into Piedmont.

However, in Catalonia, the fighting was more active. On May 27, Marshal Noailles, supported by French warships, soundly defeated the Spanish forces at the Battle of Torroella. The French then took Palamós on June 10, Gerona on June 29, and Hostalric, opening the way to Barcelona. The Spanish King threatened to make a separate peace with France if the Allies didn't help him. So, William III prepared the Anglo-Dutch fleet for action. Part of the fleet stayed in the north, first leading a failed amphibious assault on Brest on June 18, then bombing French coastal defenses at Dieppe, Saint-Malo, Le Havre, and Calais. The rest of the fleet went to the Mediterranean, joining Spanish ships. The Allied naval presence forced the French fleet back to the safety of Toulon. This, in turn, forced Noailles to retreat, harassed by Spanish militia. By protecting Barcelona this way, the Allies kept Spain in the war for two more years.

In 1695, French forces faced two major setbacks. First, Louis XIV's greatest general, Marshal Luxembourg, died on January 5. He was replaced by the Duke of Villeroi. Second, France lost Namur. In a reversal of 1692, Coehoorn led the siege of Namur under William III and other Electors. The French tried to distract the Allies by bombing Brussels. But despite a strong defense, Namur finally fell on September 5. The siege cost the Allies many men and resources and kept William III's army busy all summer. But recapturing Namur and Huy restored the Allied position and secured communications between their armies.

Meanwhile, the recent financial crisis had changed French naval strategy. England and the Dutch Republic now built and armed more ships and had a growing numerical advantage. Vauban suggested that France stop large fleet battles and instead focus on "commerce raiding," using privateers to attack enemy trade. He argued this would hurt the enemy's economy without costing Louis XIV money that was desperately needed for his armies on land. Privateers, sailing alone or in groups from French ports, had great success. For example, in 1695, the Marquis of Nesmond captured English East India Company ships said to be worth 10 million livres. In May 1696, Jean Bart broke through a blockade and attacked a Dutch convoy, burning 45 ships. In May 1697, the Baron of Pointis attacked and captured Cartagena, earning himself and the king a share of 10 million livres.

For their part, the Allied navy bombed French coastal towns like St Malo, Granville, Calais, and Dunkirk, as well as Palamos in Catalonia. The Allies sent Austrian and German reinforcements. The French replaced the sick Noailles with the Duke of Vendôme, who would become one of Louis XIV's best generals. But the balance of military power was turning against the French. In Spain, the Rhineland, and the Low Countries, Louis XIV's forces were barely holding their own. The bombing of French ports, threats of invasion, and the loss of Namur caused great worry for the King at Versailles.

At the same time, a diplomatic breakthrough happened in Italy. For two years, the Duke of Savoy's finance minister and a French commander had secretly been negotiating an agreement to end the war in Italy. The main points were the two French forts, Pinerolo and Casale, which were now cut off from French help. By now, Victor Amadeus had become more afraid of the growing Imperial power in the region than he was of the French. He knew the Imperials planned to besiege Casale, so he suggested that the French surrender the garrison to him after a small show of force. Then the forts would be destroyed and given back to the Duke of Mantua. Louis XIV had to accept. After a fake siege and brief resistance, Casale surrendered to Amadeus on July 9, 1695. By mid-September, the fort was completely destroyed.

The Road to Peace: 1696–1697

Most battlefronts were relatively quiet throughout 1696. Armies in Flanders, along the Rhine, and in Catalonia moved around but achieved little. Louis XIV's hesitation to fight the Allies, despite his generals' confidence, might have been because he knew about the secret peace talks that had started over a year earlier. By spring 1696, these talks covered all the problems blocking peace. The hardest issues were recognizing William of Orange as King of England and the status of James II in France, the Dutch demand for a barrier against future French attacks, French taxes on Dutch trade, and border settlements in the Rhine–Moselle areas. Louis XIV had managed to establish that a new treaty would be based on earlier treaties, but with the Emperor's demands for Strasbourg and William III's insistence on being recognized as King of England before the fighting ended, it seemed pointless to call for a peace conference.

In Italy, the secret negotiations were more successful. The French possession of Pinerolo was key to the talks. When Amadeus threatened to besiege Pinerolo, the French, realizing they couldn't defend it, agreed to give it back if its defenses were destroyed. These terms were formalized in the Treaty of Turin on August 29, 1696. Louis XIV also returned Montmélian, Nice, Villefranche, Susa, and other small towns. Louis XIV also promised not to interfere with Savoy's religious policy regarding the Vaudois, as long as the Duke prevented them from communicating with French Huguenots. In return, Amadeus agreed to leave the Grand Alliance and, if needed, join Louis XIV to make northern Italy neutral. The Emperor, outsmarted diplomatically, had to accept peace in the region by signing a treaty on October 7, which the French immediately agreed to. Italy became neutral, and the Nine Years' War ended in that area. Savoy emerged as an independent power.

The Treaty of Turin started a rush for peace. With trade constantly disrupted, politicians in England and the Dutch Republic wanted the war to end. France was also financially exhausted. Most importantly, Louis XIV was becoming convinced that Charles II of Spain was close to death. He knew that breaking up the alliance would be essential if France was to benefit from the upcoming battle over who would inherit the Spanish throne. The warring parties agreed to meet at Ryswick (Rijswijk) to negotiate a settlement. But as talks continued through 1697, so did the fighting. On April 16, the Allies retook Deinze. The main French goal that year in the Spanish Netherlands was Ath. Vauban and Catinat, now with troops from the Italian front, surrounded the town on May 15. After an attack on June 5, the town surrendered. The Rhineland was quiet in 1697. Although Baden took Ebernburg on September 27, news of the peace ended the campaign. In Catalonia, however, French forces, also reinforced from Italy, had great success. Vendôme, commanding about 32,000 troops, besieged and captured Barcelona. The garrison surrendered on August 10. It had been a tough fight, with many casualties on both sides.

War in North America (King William's War)

The war in Europe also affected North America, where it was called King William's War. However, the conflict in North America was very different in its meaning and size. The European war declaration came during long-standing tensions over control of the fur trade, which was very important for both French and English colonies. There was also conflict over influence with the Iroquois, who controlled much of that trade. The French wanted to hold the St. Lawrence region and expand their power over the vast Mississippi basin. Also, Hudson Bay was a point of disagreement between the English and French colonists, both claiming parts of its territory and trade. While important to the colonists, the North American part of the Nine Years' War was less important to European leaders. Despite having more people, the English colonists suffered many defeats. New France effectively organized its French soldiers, local militias, and Indian allies (like the Algonquins and Abenakis) to attack frontier settlements. Almost all resources England sent to the colonies were to defend the English West Indies, which were considered the "crown jewels" of the empire.

Problems with Native American relations got worse in 1688 with French attacks against the Iroquois in upstate New York and Native American raids against smaller settlements in Maine. The Governor General of New France, Louis de Buade de Frontenac, took advantage of the disorganization in New York and New England. He expanded the war with a series of raids on the northern borders of the English settlements. First was the destruction of Dover, New Hampshire, in July 1689, followed by Pemaquid, Maine, in August. In February 1690, Schenectady in New York was attacked. Massacres at Salmon Falls and Casco Bay followed. In response, on May 1, 1690, at a meeting in Albany, colonial representatives decided to invade French Canada. In August, a land force set off for Montreal, while a naval force sailed for Quebec. They were pushed back at Quebec, and the expedition failed. The French also retook Port Royal.

The war continued for several more years with small attacks and frontier raids. Neither the leaders in England nor France wanted to weaken their position in Europe for a big victory in North America. Under the Treaty of Ryswick, the borders of New France, New England, and New York stayed mostly the same. In Newfoundland and Hudson's Bay, French influence was stronger. But William III, who had made the interests of the Hudson's Bay Company a reason for war in North America, wasn't willing to risk his European plans for them. The Five Nations, left by their English allies, had to negotiate separately. By a treaty in 1701, they agreed to stay neutral in any future Anglo-French conflicts.

War in Asia and the Caribbean

When news of the European war reached Asia, English, French, and Dutch colonial governors and merchants quickly started fighting. In October 1690, the French Admiral Abraham Duquesne-Guitton sailed into Madras to bomb the Anglo-Dutch fleet. This attack was risky but spread the war to the Far East. In 1693, the Dutch launched an attack against their French trading rivals at Pondichéry on the south-eastern coast of India. The small French garrison surrendered on September 6.

The Caribbean and the Americas had historically been a place of conflict between England and Spain, but now they were allies. Outside North America, French interests were much smaller. Saint Kitts changed hands twice. There was occasional fighting in Jamaica, Martinique, and Hispaniola. However, suspicion between the English and Spanish limited their joint operations. The Allies had the naval advantage in these isolated areas, but it was hard to stop the French from supplying their colonial forces.

By 1693, it was clear that the campaigns in Europe hadn't dealt a decisive blow to either the Dutch Republic or England. So, the French switched to attacking their trade. The Battle of Lagos in 1693 and the loss of the Smyrna convoy caused great anger among English merchants. They demanded more protection from the navy around the world. In 1696, French naval forces and privateers went to the Caribbean hoping to capture the Spanish silver fleet. This was a double threat because capturing the silver would give France a big financial boost, and the Spanish ships also carried English goods. The strategy failed, but combined with another French expedition in 1697, it showed how vulnerable English interests were in the Caribbean and North America. Protecting them in future conflicts became very important. In May 1697, French naval forces raided Cartagena and looted the city.

The Peace of Ryswick

The peace conference started in May 1697 at William III's palace in Ryswick, near The Hague. The Swedes were the official mediators. However, the main issues were resolved through private talks between French and Dutch representatives. William III didn't want to continue the war or push for Leopold I's claims in the Rhineland or for the Spanish throne. It seemed more important for Dutch and British safety to get Louis XIV to recognize the 1688 revolution in England.

Under the terms of the Treaty of Ryswick, Louis XIV kept all of Alsace, including Strasbourg. Lorraine was returned to its duke, though France kept the right to march troops through the territory. The French also gave up all their gains on the right bank of the Rhine River. Additionally, new French forts were to be destroyed. To gain favor with Spain over the Spanish succession, Louis XIV pulled his troops out of Catalonia in Spain and several towns in the Low Countries. England and the Dutch Republic didn't ask for any territory. But the Dutch received a good trade agreement, which made it easier for Dutch trade and returned to the French tariffs (taxes on goods) from 1664. Although Louis XIV continued to shelter James II, he now recognized William III as King of England and promised not to actively support James II's son. He also gave way on the Palatinate and Cologne issues. Beyond this, the French gained official ownership of the western half of the island of Hispaniola.

Representatives from the Dutch Republic, England, and Spain signed the treaty on September 20, 1697. Emperor Leopold I, who wanted the war to continue to strengthen his claims to the Spanish throne, at first resisted the treaty. But because he was still at war with the Turks and couldn't fight France alone, he also sought terms and signed on October 30. The Emperor's finances were in bad shape, and dissatisfaction over Hanover becoming an Electorate had weakened Leopold I's influence in Germany. Protestant princes also blamed him for a religious clause in the treaty. This clause said that the lands France was giving up would remain Catholic, even those that had been forced to convert. However, the Emperor had gained a lot of power. Leopold I's son, Joseph, had been named King of the Romans, and the Emperor's candidate for the Polish throne had won over Louis XIV's candidate. Additionally, Prince Eugene of Savoy's big victory over the Ottoman Turks in 1697 led to another treaty in 1699. This strengthened the Austrian Habsburgs and shifted the balance of power in Europe towards the Emperor.

The war allowed William III to crush the Jacobite movement and bring Scotland and Ireland under more direct control. England emerged as a great economic and naval power and became an important player in European affairs. William III also continued to prioritize the safety of the Dutch Republic. In 1698, the Dutch placed troops in a series of forts in the Spanish Netherlands as a barrier against French attack. Future foreign policy would focus on maintaining and expanding these barrier forts. However, the question of who would inherit the Spanish throne was not discussed at Ryswick, and it remained the most important unsolved problem in European politics. Within three years, Charles II of Spain would be dead, and Louis XIV and the Grand Alliance would again plunge Europe into conflict – the War of the Spanish Succession.

Military Changes and Technology

New Military Tools and Tactics

The fighting season usually lasted from May to October. Winter campaigns were rare because there wasn't enough food for animals. However, the French had an advantage because they stored food and supplies in special places, allowing them to start fighting weeks before their enemies. Despite this, military operations during the Nine Years' War didn't lead to clear victories. The war was mostly about "positional warfare" – building, defending, and attacking fortresses and fortified lines. Fortresses were important because they controlled bridges and passes, protected supply routes, and served as storage areas. However, forts also made it hard to follow up on battlefield successes. Defeated armies could retreat to friendly forts, allowing them to recover and rebuild their numbers. Many less skilled commanders liked these predictable, static operations because it hid their lack of military talent. As one observer noted in 1697, armies of 50,000 men would spend the whole campaign "observing one another" and then go into winter quarters. In fact, during the Nine Years' War, armies grew to nearly 100,000 men by 1695. This put a huge strain on the finances of England and the Dutch Republic, while France struggled with a shattered economy.

Another reason for the lack of decisive action was the need to fight for resources. Armies were expected to support themselves by taxing local populations in enemy or even neutral territory. Taking resources from an area was often seen as more important than chasing a defeated army to destroy it. Financial concerns and the availability of resources were the main factors shaping campaigns, as armies tried to outlast the enemy in a long war of attrition. The only decisive action during the entire war happened in Ireland, where William III crushed James II's forces in a fight for control of Britain and Ireland. But unlike Ireland, Louis XIV's wars in Europe were never fought without compromise. The fighting provided a basis for diplomatic talks rather than forcing a complete solution.

The biggest improvement in weapon technology in the 1690s was the introduction of the flintlock musket. This new firing system allowed for faster firing and more accuracy than the older, clumsy matchlocks. But the adoption of the flintlock was slow. Until 1697, for every three Allied soldiers with new muskets, two still had matchlocks. French second-line troops used matchlocks as late as 1703. These weapons were made even better with the development of the socket-bayonet. The older plug bayonet, which was jammed into the gun barrel, stopped the musket from firing and was hard to attach and remove. In contrast, the socket-bayonet could be slid over the musket's muzzle and locked into place, turning the musket into a short pike while still allowing it to fire. The disadvantage of the pike became widely known. At the Battle of Fleurus in 1690, German battalions armed only with muskets stopped French cavalry attacks more effectively than units with pikes. Catinat even abandoned his pikes entirely before his Alpine campaign against Savoy.

In 1688, the most powerful navies belonged to France, England, and the Dutch. The Spanish and Portuguese navies had declined a lot in the 17th century. The largest French ships of the time were the Soleil Royal and the Royal Louis. While they were rated for 120 guns, they never carried that many and were too big for practical use. The Soleil Royal only sailed on one campaign and was destroyed, while the Royal Louis stayed in port until it was sold. By the 1680s, French ship design was as good as English and Dutch designs. By the Nine Years' War, the French fleet had even surpassed ships of the Royal Navy, whose designs didn't change much in the 1690s. However, innovation in the Royal Navy didn't stop. For example, at some point in the 1690s, English ships started using the ship's wheel, which greatly improved their performance, especially in bad weather. (The French navy didn't adopt the wheel for another thirty years.)

Naval battles were decided by cannon duels between ships in a line of battle. Fireships were also used but were mostly successful against anchored or stationary targets. New bomb vessels worked best for bombing targets on shore. Sea battles rarely led to clear victories. Fleets faced the almost impossible task of damaging enough enemy ships and men to win decisively. Ultimate success depended not on brilliant tactics but on sheer numbers. Here, Louis XIV was at a disadvantage. Without as much sea trade as the Allies, the French couldn't provide as many experienced sailors for their navy. Most importantly, Louis XIV had to focus his resources on the army at the expense of the fleet. This allowed the Dutch, and especially the English, to build more ships than the French. However, naval battles were relatively uncommon. Just like land battles, the goal was generally to outlast the opponent rather than destroy them. Louis XIV saw his navy as an extension of his army. The French fleet's most important role was to protect the French coast from invasion. Louis used his fleet to support land and amphibious operations or to bomb coastal targets. This was designed to draw enemy resources away from other areas and help his land campaigns in Europe.

Once the Allies had a clear advantage in numbers, the French found it wise not to challenge them in large fleet battles. At the start of the Nine Years' War, the French fleet had 118 rated ships and a total of 295 ships of all types. By the end of the war, the French had 137 rated ships. In contrast, the English fleet started the war with 173 ships of all types and ended it with 323. Between 1694 and 1697, the French built 19 large to medium-sized ships. The English built 58 such ships, and the Dutch built 22. So, England and the Dutch built ships at a rate of four to one compared to the French.

Images for kids

-

Louvois (1641–1691), Louis XIV's belligerent secretary of state at the height of his powers, by Pierre Mignard.

See also

In Spanish: Guerra de los Nueve Años para niños

In Spanish: Guerra de los Nueve Años para niños