History of Mongolia facts for kids

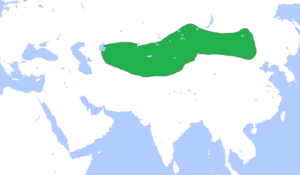

The land we know today as Mongolia has been home to many powerful nomadic empires throughout history. These included the Xiongnu (from 3rd century BC to 1st century AD), the Xianbei state (around AD 93–234), and the Rouran Khaganate (330–555). Later, the First (552–603) and Second Turkic Khaganates (682–744) also ruled this area.

Around 916, the Khitan people, who spoke a language similar to Mongol, created the Liao dynasty. Their empire stretched across Mongolia, parts of northern China, northern Korea, and the Russian Far East.

A very important moment came in 1206 when Genghis Khan united the many Mongol tribes. He turned them into a strong fighting force that built the largest connected empire in the world: the Mongol Empire (1206–1368). After this huge empire broke into smaller parts, Mongolia was ruled by the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). This dynasty was based in Khanbaliq (which is now Beijing). During this time, Buddhism in Mongolia began to spread, especially Tibetan Buddhism, as the Yuan emperors adopted it.

When the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty fell in 1368, the Mongol court moved back to the Mongolian Plateau. This started the Northern Yuan dynasty (1368–1635). The Mongols went back to their old ways of fighting among themselves and practicing shamanism. However, Buddhism became popular again in Mongolia in the 16th and 17th centuries.

By the end of the 17th century, Mongolia became part of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty. During the Xinhai Revolution in China, Mongolia declared its independence in 1911. But it took until 1921 to truly become independent and until 1945 to be recognized by other countries. Because of this, Mongolia came under strong influence from the Soviet Union. In 1924, the Mongolian People's Republic was formed. Its politics became very similar to the Soviet Union's. After the Revolutions of 1989, Mongolia had its own Mongolian Revolution of 1990 in 1990. This led to a multi-party system, a new constitution in 1992, and a move towards a market economy.

Contents

Ancient History of Mongolia

Early Life in Mongolia

The climate in Central Asia became very dry after the Indian Plate crashed into the Eurasian Plate. This huge crash created the Himalayas mountains. These mountains, along with the Greater Khingan and Lesser Khingan ranges, block warm, wet air from reaching Central Asia. Many of Mongolia's mountains formed during the Late Neogene and Early Quaternary periods. Hundreds of thousands of years ago, Mongolia's climate was much wetter.

Mongolia is famous for amazing fossil discoveries. The first dinosaur eggs ever scientifically confirmed were found here in 1923. This discovery was made by an expedition from the American Museum of Natural History, led by Roy Chapman Andrews.

Around 800,000 years ago, early humans called Homo erectus might have lived in Mongolia. While their fossils haven't been found yet, stone tools from that time have been discovered in the southern Gobi Desert. Important ancient sites include Paleolithic cave drawings in the Khoid Tsenkheriin Agui (Northern Cave of Blue) in Khovd Province. Another is the Tsagaan Agui (White Cave) in Bayankhongor Province. A neolithic farming village has also been found in Dornod Province.

Bronze and Iron Ages

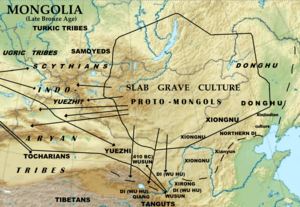

During the Copper Age and Bronze Age, people in eastern Mongolia were "paleomongolid" (early Mongol-like). In the west, they were "europid" (European-like). Horse-riding nomads lived in Mongolia during the Copper and Bronze Age Afanasevo culture (3500–2500 BC).

The Slab Grave culture existed during the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age. This culture, linked to the proto-Mongols, spread across Northern, Central, and Eastern Mongolia. It also covered parts of Inner Mongolia, Northwest China, Manchuria, Buryatia, and other nearby regions. This culture is a key archaeological find from Mongolia's Bronze Age.

Deer stones and Khirigsüürs (small kurgans or burial mounds) probably come from this time. Deer stones are ancient megaliths carved with symbols. They are found across central and eastern Eurasia, but most are in Siberia and Mongolia. There are about 700 deer stones in Mongolia. They are often found near old graves. Many believe these stones were guardians of the dead. Their true purpose and who made them are still a mystery.

An enormous Iron Age burial site from the 5th-3rd centuries BC was found near Ulaangom. It was also used by the Xiongnu later on.

By the 8th century BC, people in western Mongolia were likely Indo-European nomads, like the Scythians or Yuezhi. In central and eastern Mongolia, many other tribes were mostly Mongol in their features. By the 3rd century BC, with iron weapons, people in Mongolia started forming alliances. They lived as hunters and herders.

Early States and Empires

The Xiongnu Empire (209 BC–93 AD)

The Xiongnu empire started in Mongolia in the 3rd century BC. This marked the beginning of a true state in the region. Many scholars believe the Xiongnu people were of Mongolic origin.

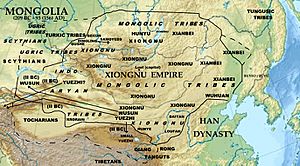

The Xiongnu first appeared strongly in the late 3rd century BC. The Chinese built the Great Wall to stop their raids. The Xiongnu leader, Modu Shanyu, united many tribes. At its strongest, the Xiongnu empire stretched from Lake Baikal in the north to the Great Wall in the south. It also went from the Tian Shan mountains in the west to the Greater Khingan ranges in the east.

In 200 BC, the Han dynasty of China tried to defeat the Xiongnu. But the Xiongnu trapped the Han Emperor Gaozu for seven days. The Emperor had to agree to a treaty in 198 BC. This treaty said that all lands north of the Great Wall belonged to the Xiongnu. China also had to send princesses and pay yearly tribute to the Xiongnu. Xiongnu raids into China continued for 70 years.

Between 130 and 121 BC, Chinese armies pushed the Xiongnu back north of the Gobi Desert. The Xiongnu capital, Luut (Dragon), was on the Orkhon River in Central Mongolia.

In AD 48, the Xiongnu empire split into southern and northern parts. The northern Xiongnu moved west. They formed the Üeban state in modern Kazakhstan and the Hunnic Empire in Europe. The Xianbei people, who were under Xiongnu rule, rebelled in AD 93. This ended Xiongnu power in Mongolia.

The Xianbei State (147–234)

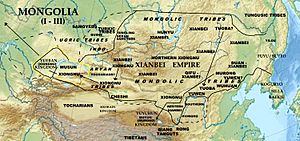

After the Xiongnu weakened, the Xianbei moved into Mongolia. They were a northern group of the Donghu, an early Mongol group. The Donghu language is thought to be proto-Mongolic.

The Xianbei grew strong from the 1st century AD. They united under Tanshihuai in 147. He pushed the Xiongnu out of Jungaria. The Xianbei also defeated a Han dynasty invasion in 167 and took over parts of northern China in 180. Most historians believe the Xianbei were a Mongolic group. They are seen as ancestors of many Mongolic peoples like the Rouran and Khitan.

The Xianbei ruler was chosen by noble leaders. They used wooden tallies called Kemu for messages. Besides raising livestock, they also did some farming and crafts. The Xianbei state broke apart in the 3rd century.

The Rouran Khaganate (330–555)

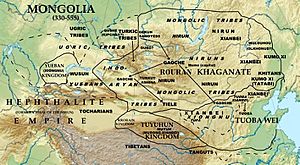

The Rouran were another branch of the Xianbei. They became a powerful nomadic empire in the late 5th century. They likely were the first to use the title khan. The Rouran ruled Mongolia, eastern Kazakhstan, and parts of China and southern Siberia. The Hephthalite Empire was a vassal state to the Rouran for 100 years.

In 402, Shelun became Khagan, marking the start of the Rouran Khaganate. The Tuoba (a Xianbei subgroup) fought many wars against the Rouran. In 552, the Altai Turkics, who were subjects of the Rouran, revolted. This uprising is often called the "Blacksmiths' rebellion." The Turkics defeated the Rouran in 555. Some Rouran people left Mongolia. Some historians believe they formed the Avarian Kaganate in Europe. The Rourans who stayed became ancestors of the Tatar tribes.

Turkic Rule (555–840)

The Göktürks (Turkics) revolted against the Rouran in 552. They became the strongest power in Central Asia. China's Northern Qi and Northern Zhou dynasties paid tribute to the Göktürks. But the new Sui dynasty in China stopped paying, leading to constant wars. The Turkic Khaganate split into Eastern and Western parts in 583.

China's Tang dynasty (618-907) later destroyed the Eastern Turks' power in 630. They took control of the Mongolian Steppes. However, the Göktürks fought back. In 682, they restored their empire, known as the Second Turkic Khaganate. This empire ended in 744, defeated by Chinese, Uyghur, and other nomadic forces.

The Uyghur State (744–840)

The Uyghurs rebelled against the Göktürks in 745. They founded the Uyghur Khaganate. The Uyghur leader Bayanchur built Ordu-Baliq City on the Orkhon River in 751. The Tang Empire even asked the Uyghurs for help to put down a rebellion in 755.

The Uyghurs developed their own writing system. Their culture and economy were more advanced than earlier groups. While some Uyghurs were Buddhists, Manichaeism became the official religion. However, most Uyghurs remained shamanists. The Yenisei Kirghiz and Karluks attacked the Uyghurs, and the Uyghur Khaganate fell in 840. This ended Turkic rule in Mongolia.

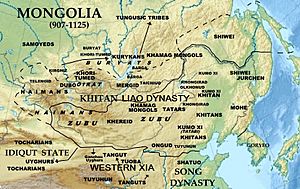

The Liao Dynasty (916–1125)

The Khitans were an ethnic group whose language was related to Mongolic languages. Their leader Yelü Abaoji became emperor in 916 and started the Liao dynasty. The Liao dynasty ruled a large part of Mongolia, including the basins of the Kherlen, Tuul, and Orkhon rivers. They also took over areas left by the Turkic Uyghurs.

The Liao dynasty grew strong and took over parts of northern China, including modern-day Beijing. By the mid-10th century, Khitan leaders were emperors of northern China. The Khitans built cities and controlled their farming subjects.

The empire had two parts: one for herders in the north and one for farmers in the south. They traded actively. The Khitans developed their own writing systems based on Chinese and Uyghur scripts. Printing technology also developed in the Liao territory.

A Tungusic people called the Jurchens (ancestors of the Manchus) allied with the Song dynasty. They defeated the Liao dynasty in a seven-year war (1115–1122). The Jurchen leader Wanyan Aguda started a new empire, the Jin dynasty. The Liao dynasty fell in 1125. Some Khitans fled west and founded the Western Liao dynasty (1124–1218) in present-day Xinjiang and eastern Kazakhstan. In 1218, Genghis Khan destroyed the Western Liao.

Medieval Mongolia

Mongol Tribes in the 12th Century

The 12th century in Mongolia was a time of competition between many tribes and alliances (khanates). A group of tribes called "Mongol" had been known since the 8th century. Some Shiwei tribes are thought to be ancestors of the Mongols.

The main Mongol tribes were forming a state in the early 12th century. This was known as the Khamag Mongol confederacy. Most people in Mongolia at this time worshipped spirits, with shamans guiding them.

The Khamag Mongols lived in a fertile area around the Onon, Kherlen, and Tuul rivers. The first known khan of Khamag Mongol was Khabul Khan. He fought off invasions from the Jin dynasty. After him, Ambaghai Khan was captured by the Tatars and cruelly executed by the Jurchens. Ambaghai's successor, Hotula Khan, fought 13 battles against the Tatars to get revenge.

After Hotula died, the Khamag Mongol couldn't choose a new khan. However, Khabul's grandson, Yesukhei baghatur, was a powerful chief. Yesukhei was poisoned by the Tatars in 1171 when his eldest son, Temujin, was only 9 years old. After Yesukhei died, Temujin and his family were left without support. The Khamag Mongol remained in a political crisis until 1189.

In the 12th century, the Khamag Mongol Khanate, Tatar confederation, Keraite Khanate, Merkit confederation, and Naiman Khanate were the five main Mongol tribal groups in the Mongolian plateau. Most Mongol tribes were Shamanists, but some, like the Keraites, practiced Nestorian Christianity.

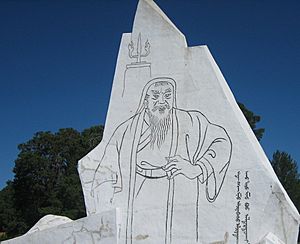

Genghis Khan Unites the Mongols

Temujin (1162–1227) defeated the "Three Mergids" in 1189 with help from Tooril Khan of Kereit and his blood brother Jamukha. The Mergids had attacked Temujin's home and captured his wife, Börte. Temujin's fight to free his wife helped him gain fame. After defeating the Mergids, Temujin's reputation grew quickly. The Mongol nobles then crowned him Chinggis Khan (Genghis Khan), meaning "Oceanic Khan" or "Universal Ruler," as the leader of Khamag Mongol.

Temujin and Tooril Khan allied with the Jurchens to defeat the Tatars. Tooril Khan was given the title "Wang" (king) by the Jin court, becoming Wang Khan. By 1201, the Taichuud and Jurkhin tribes were defeated. More and more nobles from other tribes joined Temujin.

In 1201, Wang Khan's siblings allied with Inancha Khan of Naiman and defeated Wang Khan. Temujin helped Wang Khan regain his power. Temujin finally defeated the Tatars in 1202. Wang Khan's son, Sengum, became jealous of Temujin's growing power and convinced his father to fight Temujin. This led to Temujin's victory and the conquest of the Kereit Khanate. Wang Khan fled but was killed by Naiman patrols.

Tayan Khan of Naiman and his son Kuchlug started a campaign against Temujin in 1204. They allied with Jamukha. Temujin used a clever trick: he ordered each of his warriors to light ten campfires, making his army look much larger. This scared Tayan Khan. Temujin won the battle. Kuchlug escaped to Gur-Khan of Kara-Kitai.

After conquering the Naiman Khanate, Temuj's brother, Khasar, found a dignitary named Tata Tunga. He spread the Uighur alphabet among the Mongols, which became the basis for the Classical Mongol script.

By 1206, Temujin led all the tribes of the Mongolian steppe. His success came from his flexibility, his loyalty to friends, and his smart tactics. In 1206, a meeting of Mongol nobles on the Onon River officially crowned Temujin as Chingis Khaan (Genghis Khan), Emperor of all Mongols.

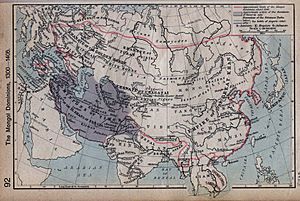

The Great Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire and the states that came from it were very important in the 13th and 14th centuries. Genghis Khan and the leaders after him conquered almost all of Asia and parts of Europe.

Genghis Khan changed how the tribes were organized. He divided the country into 95 mingats. This was a decimal system: 10 warriors made an arbatu, 10 arbatus made a zagutu (100 warriors), 10 zagutus made a mingat (1,000 warriors), and 10 mingats made a tumen (10,000 warriors). This system was inherited from the Xiongnu. It's estimated that Mongolia had at least 750,000 people and 95,000 cavalrymen at this time.

The new Great Mongol State attracted many nearby peoples. Starting in 1207, the Uighur state, the Taiga people, and the Karluk kingdom joined Mongolia. Genghis Khan wanted to make his young nation strong. For a century, the Jin dynasty had tried to turn Mongol tribes against each other. To test his army and prepare for war with the Jin dynasty, Genghis Khan conquered the Tangut-led Western Xia, who then became his vassals.

In 1211, the Mongols, with over 90,000 cavalrymen, began a war with the Jin dynasty. They crossed the Great Wall and invaded Chinese provinces. The Jin Emperor surrendered in 1214. He gave Genghis Khan a princess and tribute of gold and silver. Genghis Khan then ordered his general Mukhulai to finish conquering the Jin dynasty and returned to Mongolia.

Later, the general Jebe defeated Kuchulug, who had become the Gur-Khan of Qara Khitai. Kuchulug's power was weak because he, as a Buddhist, treated the local Muslim people badly.

Genghis Khan wanted to have good relations with the Khwarezm Empire. This empire controlled important trade routes in Central Asia, Iran, and Afghanistan. But the Khwarezm Shah believed he should be the only ruler. When the Shah executed 450 of Genghis Khan's envoys and traders in 1218, it started a war.

The Mongol troops invaded the Khwarezm Empire in 1219. Even though the Shah had a much larger army, he didn't fight back well. The Mongols destroyed cities like Otrar, Buhara, Merv, and Samarkand. Shah's son Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu fought bravely in 1221 but was defeated and fled.

In 1220, Mongol scout groups led by Jebe and Subedei conquered northern Iran. They invaded Iraq, Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia in 1221. They then entered the lands of the Kipchak Khanate near the Black Sea. The Kipchaks allied with the Rus princes. They fought the Mongols at the Kalka River in May 1223 but were defeated.

The Western Xia refused to help Genghis Khan in his western campaigns. So, after returning to Mongolia, the Mongol army invaded Western Xia in 1226. They conquered its capital, Zhongxing, in 1227.

Genghis Khan's 16-year conquests led to the huge Mongol Empire. He died on August 16, 1227.

The Mongol Empire and Pax Mongolica

In 1228, a meeting of nobles called the Kurultai chose Ogedei as the new Great Khan, just as Genghis Khan had wanted. Ogedei Khan made Karakorum on the Orkhon River the capital of the Mongol Empire. Karakorum had been a military base since 1220. The city had 12 Buddhist temples, two Muslim mosques, and one Christian church. This shows that the Mongols were tolerant of all religions.

Ogedei Khan created a good postal system called yam with well-organized posts. This system connected all parts of the huge empire. Ogedei Khan finished conquering the Jin dynasty between 1231 and 1234. He sent armies led by Batu Khan to the west. They conquered 14 Russian states between 1236 and 1240. They also invaded Poland, Hungary, and other areas in 1241–1242.

Ogedei Khan died in 1241. After his death, there was a struggle for who would be the next Great Khan. In 1246, the Kuriltai chose Guyug, Ogedei's son. Guyug Khan died in 1248.

In 1251, the Kuriltai chose Mönghe, son of Tului, as Great Khan. Mönghe Khan sent his brother Hulagu to conquer Iran. Hulagu conquered Iran in 1256 and Baghdad, the Caucasus, and Syria between 1257 and 1259.

Mönghe Khan died in 1259. In 1260, the Kuriltai chose Ariq Böke, Mönghe's youngest brother, as Great Khan. But the same year, Mönghe's other brother, Kublai, who was fighting in China, declared himself Great Khan in Shangdu. This led to the Toluid Civil War between the two brothers from 1261 to 1264, until Ariq Böke surrendered.

The Mongol Empire had a big impact on the social, cultural, and economic life of people across Eurasia in the 13th and 14th centuries. It helped share knowledge, inventions, and culture between the West and East. This time is called Pax Mongolica, or "Mongol Peace." In Mongolia, Genghis Khan left behind a strong legal code, a written language, and a sense of national pride.

The Yuan Dynasty and Its Breakup

The creation of the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) by Kublai Khan sped up the breakup of the Mongol Empire. The empire split into four main parts: the Yuan dynasty in China, and three western khanates: the Golden Horde, the Chagatai Khanate, and the Ilkhanate.

Many Mongols did not like Kublai Khan moving the capital from Karakorum to Khanbaliq (modern Beijing) in 1264. Ariq Böke fought to keep the empire's center in Mongolia. After Ariq Böke's death, Kaidu, a grandson of Ogedei Khan, continued this fight until 1301.

Kublai Khan invited Drogön Chögyal Phagpa, a lama from the Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism, to spread Buddhism. Buddhism became the main religion of the Mongol Yuan state. In 1269, Kublai Khan asked Phagpa lama to create a new writing system for the empire's many languages. The 'Phags-pa script was based on Tibetan script and was used for Mongolian, Tibetan, Chinese, and Sanskrit.

Kublai Khan announced the Yuan dynasty in 1271. It included modern-day Mongolia, the lands of the former Jin and Song dynasties, and parts of southern Siberia. Kublai divided people into four ranks. Mongols were highest, then people from west of Mongolia, then people from the former Jin dynasty, and finally, people from the former Song dynasty (Han Chinese).

Mongolia itself had a special status during the Yuan dynasty. But by the early 14th century, it became a province called Lingbei Branch Secretariat. When the Ming dynasty (founded by Han Chinese) captured the Yuan capital in 1368, the last Yuan emperor, Toghon Temür, fled north. The Mongols retreated to the Mongolian steppe. This started the Northern Yuan dynasty, which lasted until the 17th century.

The Northern Yuan and Oirats

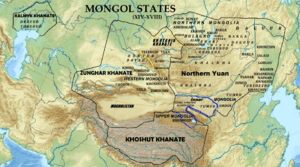

After 1368, the Mongols who had ruled the Yuan dynasty were pushed out of China. The remaining Mongol state is called the Northern Yuan dynasty. It was also known as the "Forty and the Four," meaning the 40 tumens (groups of 10,000 warriors) of the Mongols and the 4 tumens of the Oirats.

Biligtü Khan Ayushiridara became khan in 1370. The Ming dynasty attacked the Northern Yuan from 1372. Mongol general Köke Temür defeated a large Ming army in 1373. The Ming army looted Karakorum in 1380, but later Ming invasions were pushed back.

The Ming dynasty realized it couldn't conquer Mongolia by force. So, it started a policy of making Mongol groups fight each other. They also created economic blockades. This led to a long period of fighting among Mongol leaders in the 15th century.

The Mongols were powerful even after the Yuan dynasty fell. But their numbers decreased due to wars and mixing with other groups. Only 6 tumens were able to retreat to Mongolia. These were grouped into 3 tumens of the left wing (ruled by the Mongol Khan) and 3 tumens of the right wing (ruled by the Jinong, a vassal of the Khan).

The Oirats formed another 4 tumens. They stayed in Mongolia during the Yuan dynasty. By the 15th century, the Oirats lived in the Altai Mountains region. They were ruled by a Taishi, who was a vassal of the Khan.

In the late 14th century, Mongolia was divided into Western Mongolia (Oirats) and Eastern Mongolia (Khalkha, Southern Mongols, Buryats). The Oirats and Eastern Mongols fought for control, which weakened Mongolia.

In 1434, Western Mongolian Togoon Taishi united the Mongols. He died in 1439, and his son Esen Taish became prime minister. Esen Taishi made the Oirats very powerful. He traded with the Ming dynasty. When diplomacy failed, he led a military campaign in 1449. A huge Ming army was defeated by a much smaller Oirat army. The Ming Zhengtong Emperor was captured, and Beijing was attacked. Esen Taishi then declared himself Khan. But his reign was short; his rivals rebelled and overthrew him in 1454.

The Khalkha people became a dominant Mongol group during the reign of Dayan Khan (1479–1543). Mongolia was united again under Queen Mandukhai the Wise and Batmönkh Dayan Khan. Queen Mandukhai defeated the Oirats. Dayan Khan moved his home to Chaharia to better control the right-wing tumens. The Mongol Khans lived in Chaharia until 1634.

Mongolia was voluntarily reunited for the last time under Eastern Mongolian Tümen Zasagt Khan (1558–1592). During his rule, the right-wing tumens rose under a local lord named Altan Khan. Altan Khan attacked the Ming dynasty but signed a peace treaty in 1571. He built the city of Hohhot in 1557.

Abtai Sain Khan, the ruler of Khalkha, conquered the Oirats in the 1570s. But the Oirats rebelled in 1588.

Tümen Jasagtu Khan was followed by Buyan Sechen Khan. His grandson Ligden became khan in 1603. He started translating important Buddhist scriptures into Mongolian. By his time, the power of the Northern Yuan khan had weakened. Ligden tried to unite Mongolia peacefully, but when that failed, he used force. This made the local lords of Inner Mongolia turn against him.

Trade with China was often difficult. The Ming government banned selling metal products to Mongols, fearing they would be made into weapons. But metal items like kettles were essential for herders. This ban and low prices for Mongol goods often led to conflicts.

Cities in Mongolia were destroyed by Chinese raids in the late 14th and early 15th centuries. This meant there wasn't a good system of trade between cities and rural areas. Some attempts were made to grow crops in the 16th and 17th centuries, but these mostly helped the ruling classes, not ordinary Mongols.

By the end of the 16th century, several Khanlig dynasties developed in Khalkha. Northern Khalkha (modern Mongolia) was divided among the sons of Gersenz Hongtaiji. Abtai, one of Gersenz's grandsons, received the title of Khan from the Dalai Lama. His son founded the dynasty of the Tushiyetu Khans in central Khalkha. Other grandsons started the Secen Khans in the east and Zasagtu Khans in the west.

In the early 17th century, the Khoshut tribe of Oirat moved to Kukunor. The Torghuts moved to the Volga River basin, becoming the Kalmyk people. Khara Khula united the Oirats by the 1630s. His son Erdeni Batur Hongtaiji established the Dzungar Khanate in 1634.

Buddhism Returns to Mongolia

In 1566, Hutuhtai Secen Hongtaiji of Ordos invaded Tibet. He demanded that the Tibetan clergy submit. They agreed, and he returned with three high-ranking monks. Tumen Jasaghtu Khan invited a monk from the Kagyu school in 1576.

Following his nephew's advice, Altan Khan of Tumet invited the head of the Gelug school, Sonam Gyatso, to his land. When they met in 1577, Altan Khan recognized Sonam Gyatso as a reincarnation of Phagpa lama. Sonam Gyatso, in turn, recognized Altan as a reincarnation of Kublai Khan. This helped Altan gain more power as "khan." Sonam Gyatso also gained support for his leadership over Tibetan Buddhism. From this meeting, the heads of the Gelugpa school became known as Dalai Lamas.

At the same time, Abtai, the ruler of Khalkha, also met the new Dalai Lama. He asked for the title of Khan. The Dalai Lama first refused, saying there couldn't be two Khans at once. But after some thought, he gave Abtai the title Khan. Abtai Khan built the Erdene Zuu monastery in 1585 at the site of the old city of Karakorum. Eventually, most Mongolian rulers became Buddhists.

A Time of Culture and Learning

The late 15th and 16th centuries saw a rebirth of Mongolian culture. Architecture, fine arts like silk applique, thangka painting, and sculpture all developed.

Zaya Pandita Namhaijamtso (1599–1662), an adopted son of Oirat noble Baibagas, improved the Mongolian script. This new script, called Todo bichig, was made for the Oirat dialect.

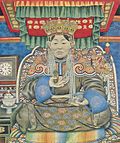

Zanabazar (1635–1723), the head of Buddhism in Khalkha, was a great artist. He created beautiful sculptures, including the famous Sita Tara and Siyama Tara. He also designed the Soyombo script in 1686 for Mongolian, Tibetan, and Sanskrit languages.

The mathematician and astronomer Minggatu discovered nine trigonometric equations. He wrote many books on mathematics and linguistics. In history and literature, important works like the Shira Tuuji (16th century), Altan Tobchi (early 17th century), and Erdeniin Tobchi (1662) were written. Tsogtu Hongtaiji wrote famous philosophical poems in the 1620s. Legdan Hutuhtu Khan had the 108 volumes of Kangyur and 225 volumes of Tengyur translated into Mongolian.

Mongolia Under Qing Rule

Qing Conquests

In the early 17th century, the Northern Yuan dynasty was divided into three parts: the Khalkha, Inner Mongols, and Buryats. By the end of the 17th century, the power of the all-Mongolian Khan had weakened. The Mongols faced a new, rising Jurchen state in the east. The last Mongol Khagan was Ligdan Khan in the early 17th century. He had conflicts with the Manchus and angered most Mongol tribes.

In 1618, Ligdan signed a treaty with the Ming dynasty to protect their northern border from Manchu attacks. Nurhaci, who united the Jurchen tribes, asked Ligdan Khan for an alliance against the Ming dynasty. Ligdan refused, saying he ruled 40 tumens of Mongols, while Nurhaci only ruled three Jurchen tumens. Nurhaci then allied with Ligdan Khan's vassals, the princes of Southern Khalkha and other Inner Mongol groups. They defeated Ligdan Khan in 1622.

By the 1620s, only the Chahars remained under Ligdan's rule. The Chahar army was defeated by Inner Mongol and Manchu armies in 1625 and 1628. Ligdan Khan died in 1634 from an epidemic while on his way to Tibet.

Hong Taiji, Nurhaci's successor, took the title of Khan of the Mongols in 1636. This marked the conquest of Inner Mongolia. The Qing dynasty, supported by Inner Mongol troops, conquered the Ming dynasty in 1644.

Erdeni Batur Hongtaiji of the Dzungar Khanate called a meeting of Western and Eastern Mongols in 1640. They wanted to unite against growing foreign aggression. This meeting created the "Great Code of the Forty and the Four," or "Mongol-Oirat Code."

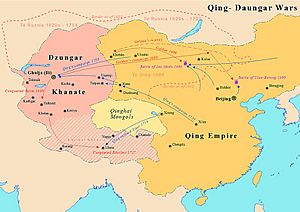

A conflict between Khalkha and Dzungaria began in 1688. Galdan Boshugtu Khan, king of the Dzungar Khanate, conquered Khalkha. The head of Khalkha Buddhism, Boghda Zanabazar, and the Khalkha khans fled to Inner Mongolia, which was already part of the Qing dynasty. Some Khalkhas fled north to Russia.

The Khalkha leaders asked the Manchu Qing dynasty for help against Galdan. The Kangxi Emperor of the Qing dynasty demanded that they become his vassals first. Galdan was defeated near UlaanBudan and fled.

In 1689, Galdan's brother, Tsewang Rabtan, took over the Dzungar throne. This made it hard for Galdan to fight the Qing Empire. Galdan sent his army to "free" Inner Mongolia and called on Inner Mongol nobles to fight for independence. Some supported him, but Inner Mongol nobles did not join the battle against the Manchus.

The Kangxi Emperor held a meeting of Khalkha and Inner Mongol rulers in Dolnuur in 1691. There, the Khalkha leaders formally pledged loyalty to the emperor. However, Khalkha was still mostly under Galdan Boshugtu Khan's rule. Qing forces invaded Khalkha in 1696. The Oirats were defeated in a battle at Zuun Mod. Galdan Boshugtu Khan died in 1697.

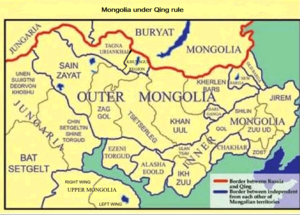

Mongolia also faced Russian expansion in the 17th century. The Buryats fought against Russian invasion from the 1620s. The Russians brutally put down Buryat resistance and conquered the Baikal region. The Buryat region was officially added to Russia by treaties in 1689 and 1727. These treaties set the northern border of Mongolia.

Tsewang Rabtan stopped the eastern expansion of the Kazakh khans. He also sent his general to conquer Tibet in 1716. His forces were driven out by Qing troops in 1720, who then occupied Tibet. Several Qing attempts to conquer the Dzungar Khanate failed in the early 18th century.

Tsewang Rabtan was followed by his son Galdan Tseren in 1727. Galdan Tseren worked to develop farming and cannon making in Dzungaria. He successfully fought off Qing attacks from 1729–31. Galdan Tseren died in 1745. A struggle for power began among his heirs. Dawachi, supported by Khoi-Oirat prince Amursana, became the new Dzungar Khan in 1753.

Dawachi then fought Amursana and defeated him. Amursana allied with the Qing dynasty, hoping to become Khan with their help. The Qing army, with 200,000 troops from Khalkha, Inner Mongolia, Manchu, and Chinese soldiers, invaded Dzungaria in 1755. The Dzungar Khanate was conquered by the Manchus between 1755 and 1758.

After the conquest, Amursana, King Chingünjav of Khotogoid, and Inner Mongolian Khorchin Wang Sevdenbaljir rebelled against Qing rule. Some Inner Mongol and Khalkha nobles supported this uprising.

Chingünjav rebelled in 1756, calling on other Khalkha nobles to fight for independence. But the Qing court captured Chingünjav before the uprising fully started. Chingünjav and his family were cruelly executed in 1757. The Qing court decided that future Jebtsundamba Khutughtus (religious leaders) would only be found in Tibet, not Mongolia.

Amursana returned to Dzungaria and was made Khan by some Oirat nobles in 1756. But his followers were not united. After a battle in 1757, Amursana was defeated and fled to Russia. The Dzungars continued fighting the Manchu invasion until 1758. The Qing army carried out a terrible Dzungar genocide, killing most of the Oirat people. Of 600,000 Dzungars, only 30,000 survived. The Dzungar Khanate's land became part of the Qing Empire as Xinjiang.

Mongolia Under Qing Rule

After taking control of Outer Mongolia, the Qing government divided Khalkha into four aimags (provinces). The Oirat territories in the Kobdo region were also grouped into aimags. These aimags were governed by congresses of local lords.

Mongolian nobles, who ruled their local areas, had to provide military service, attend the Emperor's hunts, gather resources, and put down local riots. They were rewarded for their service, sometimes even marrying a princess. Disobedience was severely punished.

The heaviest burden fell on ordinary Mongolian workers. They became poor from providing horses and livestock for military campaigns. They also had to serve as warriors themselves. During Qing rule, a system similar to serfdom was introduced. There were state serfs, personal serfs of nobles, and serfs of religious leaders.

To prevent Mongols from mixing with Han Chinese, the Qing government tried to limit Chinese travel to Khalkha and forbid marriages between Mongols and Han Chinese. However, in the early 20th century, the Qing policy changed. They started "New Policies" to make Mongolia more Chinese by encouraging Han Chinese to settle there.

Modern Mongolia

The Bogd Khanate (1911–1919)

The official name of the new state was "Ikh Mongol Uls," meaning the "Great Mongolian State." Yuan Shikai, the President of the new Republic of China, claimed Outer Mongolia as part of China. The Qing Emperor's abdication decree said that the lands of the five races (Manchu, Han, Mongol, Hui, and Tibetan) would form one great Republic of China. However, Mongols believed their loyalty was to the Qing monarch, not to China. When the Qing dynasty fell in 1911, Mongols felt their agreement with the Manchus was no longer valid.

Bogd Gegeen was crowned as Bogd Khaan (Holy King) of Mongolia on December 29, 1911. A new era began. Mongolian troops took control of Khalkha and the Khovd region. Many Mongol leaders outside Outer Mongolia supported Bogd Khan's call for Mongolian reunification.

On February 2, 1913, the Bogd sent Mongolian cavalry to "liberate" Inner Mongolia from China. The Russian Empire refused to sell weapons to Mongolia. Russia was worried that if Mongols gained independence, other Central Asian groups might also revolt. About 10,000 Mongolian cavalry fought 70,000 Chinese soldiers and controlled almost all of Inner Mongolia. But in 1914, the Mongolian army had to retreat due to lack of weapons.

The Barga Mongols fought Chinese forces in August 1912 and wanted to unite with the Bogd Khaanate.

The establishment of the Bogd Khaanate was very important, like the founding of the Mongol Empire in 1206. Mongolia began to modernize. A parliament with two chambers was formed in 1914. A new legal code was adopted in 1915.

On November 3, 1912, Russia and Mongolia signed a treaty without China. This meant Russia recognized the Bogd Khaan as the ruler of a sovereign "State of Mongolia." However, under pressure from Russia and China, the Treaty of Kyakhta (1915) "downgraded" Outer Mongolia's independence to autonomy within China. Mongolia wanted full independence for all Mongol lands, but had to accept Russia's position. Outer Mongolia remained mostly free from Chinese control.

On February 2, 1913, Mongolia and Tibet signed a friendship and alliance treaty.

Chinese Occupation (1919–1921)

After the Russian Revolution of October 1917, China again claimed Outer Mongolia. In late 1919, Chinese general Xu Shuzheng occupied Urga (now Ulaanbaatar). He forced the Bogd Khaan and nobles to sign a document giving up Mongolia's independence. Mongolian independence leaders were arrested and tortured. China tightened its control over Mongolia.

Russian White Guard troops, led by Baron Ungern von Sternberg, invaded Mongolia in October 1920. Ungern wanted allies against the Soviet Union. He attacked the capital, Niislel Khuree (Urga), but was pushed back. Ungern then contacted Mongolian nobles and lamas. He received Bogd Khaan's order to regain independence. On February 2–5, 1921, Ungern's forces drove the Chinese out of the capital. The Bogd Khaan's government was briefly restored.

The Mongolian People's Republic (1921–1992)

The Mongolian People's Party (MPP) was formed in early 1921. It was a merger of two revolutionary groups. They sought help from the Soviet Union. Bogd Khan supported the MPP's request to the Soviets for the sake of independence. The Soviet Union chose to support the MPP as the future rulers of Mongolia.

The Mongolian Revolution of 1921 began on March 18. Volunteer troops led by Sukhbaatar attacked the Chinese garrison at Kyakhta. Mongolian and Soviet Red Army troops advanced south, defeating Chinese and Ungern's White troops. The MPP and Russian Red Army entered Urga in July 1921. This revolution ended Chinese occupation and defeated White Russian forces in Mongolia.

Before the 1921 revolution, Mongolia's economy was very basic, based on animal husbandry by nomads. Farming and industry barely existed. Most people were illiterate nomadic herders. Much of the male workforce lived in monasteries. Livestock belonged mainly to nobles and monasteries. Chinese or other foreigners controlled most other businesses. Mongolia's new leaders faced a huge challenge to build a modern economy.

In 1924, during secret talks with China, the Soviet Union agreed to China's claim to Mongolia. But the Soviet Union officially recognized Mongolia's independence in 1945.

The revolutionary government kept Bogd Khan as the head of state, but the MPP and Soviet advisors held the real power. After Bogd Khan's death in 1924, the MPP quickly created a Soviet-style constitution. They ended the monarchy and declared the Mongolian People's Republic on November 26, 1924. Mongolia became isolated from the world as it followed the Soviet Union's communist path. This also protected it from potential Chinese aggression.

In 1928, Mongolian politics became very strict. Herds were forced into collective farms. Private trade was forbidden. Monasteries and nobles were attacked. This led to economic problems and widespread unrest and armed uprisings in 1932. The MPP and Soviet troops defeated the rebels.

As a result, the MPP eased its strict policies, following advice from the Comintern. This "Policy of the New Turn" allowed for some economic freedom. However, another wave of harsh actions began in 1937, led by Khorloogiin Choibalsan. This almost completely wiped out the Buddhist clergy. Many Buryat Mongols and 22,000–33,000 Mongols were killed. These victims included monks, nationalists, military officers, nobles, and ordinary citizens.

In 1939, Soviet and Mongolian troops fought Japan in the Battle of Khalkhyn Gol in Eastern Mongolia. In August 1945, at the end of World War II, Mongolian troops helped the Soviets against Japan in Inner Mongolia.

Also in August 1945, China finally agreed to recognize Mongolia's independence if a vote was held. The vote took place on October 20. The official result was 100% for independence.

After the Communist victory in China in 1949, Mongolia had good relations with both its neighbors. When the Sino-Soviet split happened in the 1960s, Mongolia strongly sided with the Soviet Union. In 1960, Mongolia gained a seat in the UN.

The years after the war saw faster progress towards a socialist society. In the 1950s, livestock was again collectivized. State farms were created. With much help from the USSR and China, projects like the Trans-Mongolian Railway were completed. In the 1960s, Darkhan city was built with help from Soviet and other COMECON countries. In the 1970s, the Erdenet mining complex was created.

Democracy in Mongolia

A small meeting organized by the Mongolian Democratic Union on December 10, 1989, marked the start of the Democratic Movement in Mongolia. More and more people joined later meetings. A huge meeting with 100,000 people took place on March 4, 1990. Demonstrators marched to the government building, demanding the resignation of the ruling party's leaders and political reforms.

When the Communist government refused, activists began a hunger strike from March 7–10, 1990. This led to the resignation of the ruling party's leaders and talks about political reforms.

The first democratic election was held in July 1990. The People's Republic of Mongolia officially ended on February 13, 1992.

In June 2021, former Prime Minister Ukhnaa Khurelsukh became Mongolia's sixth democratically elected president.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Mongolia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Mongolia para niños

- Architecture of Mongolia

- Central Asian studies

- Culture of Mongolia

- Geography of Mongolia

- History of Central Asia

- History of East Asia

- List of sovereign states by date of formation

- List of country name etymologies

- Mongolian nobility

- Mongolian plateau

- Outline of Mongolia

- Politics of Mongolia

- Timeline of Mongolian history

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |