Union Army facts for kids

During the American Civil War, the United States Army was the main land force that fought to keep the United States together. People often called it the Union Army, the Grand Army of the Republic, the Federal Army, or the Northern Army. This army was very important in saving the United States as a strong country.

The Union Army included the regular soldiers of the United States. But it also had many temporary groups of volunteers and people who were drafted into service. The Union Army fought against the Confederate States Army and eventually won.

Over the course of the war, more than 2.1 million men joined the Union Army. This included nearly 179,000 African American soldiers. About 25% of the white soldiers were immigrants, and another 25% were first-generation Americans. Sadly, about 596,000 soldiers were killed, wounded, or went missing. Many men first joined for just three months, but then chose to stay for three more years.

Contents

Forming the Union Army

When the American Civil War started in April 1861, the U.S. Army was quite small. It had only about 16,367 soldiers and 1,108 officers. These troops were spread out across the country, mostly in the West.

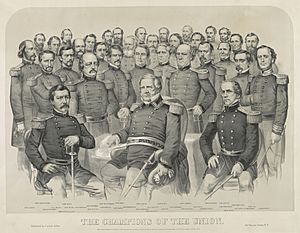

About 20% of the officers, many from the Southern states, left the U.S. Army. They chose to join the Confederate States Army. However, many former U.S. Military Academy graduates, like Ulysses S. Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman, returned to serve the Union.

When the Southern states left the United States, President Abraham Lincoln asked the states to gather 75,000 troops. These troops were meant to stop the rebellion and protect Washington, D.C.. This call made some border states choose sides, and four more states joined the Confederacy.

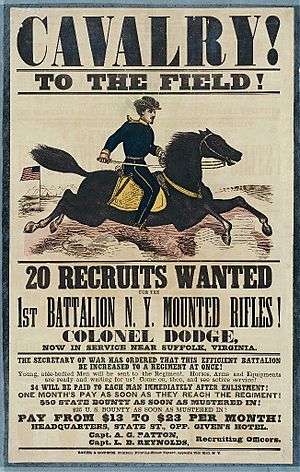

The war turned out to be much longer and bigger than anyone expected. On July 22, 1861, Congress allowed a volunteer army of up to 500,000 troops. Many Northerners, abolitionists, and immigrants eagerly joined at first. They were patriotic or sought a steady income.

As the war continued, fewer people volunteered. So, the government offered money bonuses and started forced drafting. Many Southern Unionists, white soldiers from Confederate states, also fought for the Union Army.

Some people thought the South had an advantage because many professional officers joined the Confederacy. However, more West Point graduates actually served the Union. For example, Robert E. Lee was offered command of the Union Army but chose to lead Virginia's forces instead. He later became the main commander of the Confederate army.

How the Union Army Was Organized

Who Led the Army?

U.S. President Abraham Lincoln was the top leader of the Army. He was the commander-in-chief. Below him was the Secretary of War, who managed the Army's daily business. The general-in-chief led the Army's operations in the field.

Several people served as general-in-chief during the war:

- Winfield Scott: 1841–1861

- George B. McClellan: 1861–1862

- Henry W. Halleck: 1862–1864

- Ulysses S. Grant: 1864–1869

When there was no general-in-chief, President Lincoln and Secretary Stanton directly controlled the Army. They had help from a group called the "War Board."

Main Army Groups

The Union Army was divided into many groups, usually based on geography.

- Military Divisions: These were large areas, like a modern-day theater of war. They included several Departments and reported to one commander.

- Departments: These covered specific regions. They were in charge of military bases and armies in their area. Departments were often named after rivers or regions.

- Districts: These were smaller parts of a Department. Some smaller areas were called Subdistricts.

- Armies: These were the fighting forces. An army usually had between one and eight corps, with three being common. Famous armies included:

- Army of the Cumberland: Fought in Tennessee and Georgia.

- Army of the Potomac: The main army in the East.

- Army of the Tennessee: The most famous army in the West.

Each of these armies was usually led by a major general. The commander of a Department or District often led the army in that area too.

Smaller Army Groups

The Union Army used a system based on European traditions. The regiment was the main unit for recruiting, training, and fighting. However, units could vary greatly in size.

| Name | Commander | Sub-units | Soldiers | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corps | Major general | 2–6 divisions | 36,000 | Usually had three divisions. Included an artillery group after 1863. |

| Division | Major general | 2–6 brigades | 12,000 | Usually had three brigades for infantry. Included artillery until 1863. |

| Brigade | Brigadier general | 2–12 regiments | 4,000 | Usually had four regiments for infantry and cavalry. |

| Regiment | Colonel | 10 companies | 1,000 | Actual size changed as soldiers were lost in battle. |

| Battalion | Major | Varied | Varied | Two or more companies of a regiment, or a regiment with 4-8 companies. |

| Company | Captain | 2 platoons | 100 | Cavalry companies were called troops. Artillery companies were called batteries. |

People in the Union Army

Regulars vs. Volunteers

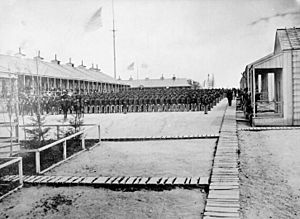

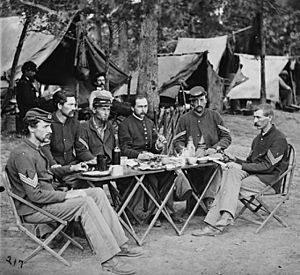

Most soldiers fighting for the Union were volunteers. Before the war, the Regular Army had about 16,400 soldiers. By the end of the war, the Union Army had over a million soldiers, but only about 21,699 were Regulars. Most new soldiers preferred to join the Volunteer forces.

Many Americans before the war didn't like the idea of a large standing army. They preferred "citizen soldiers" (militia) who would only fight when needed. This idea continued during the Civil War. Many people believed the volunteers, not the Regular Army, won the war.

However, the Regular Army was very important. In the early First Battle of Bull Run, Regulars protected the retreat while volunteers fled. Regular officers also trained the volunteers, especially in important tasks like managing supplies. Regular artillery units were particularly good at training their volunteer counterparts.

Regular soldiers were highly skilled. At the Battle of Gettysburg, their fighting ability impressed many, including Prince Philippe, Count of Paris. Volunteers looked up to the Regulars as the standard for how soldiers should fight.

Officers

Union Army officers had different ranks. These included general officers (like Lieutenant General, Major General, and Brigadier General), field officers (like Colonel, Lieutenant Colonel, and Major), and company officers (like Captain, First Lieutenants, and Second Lieutenants).

The President appointed all Regular officers and general officers in the Volunteer forces. Volunteer field and company officers could be appointed by the President or their state Governor. Company officers were often chosen by the soldiers in their company. This system sometimes led to less experienced leaders being promoted. But as the war went on, promotions were more often based on skill in battle.

Officers often faced more danger in battle because they led from the front. Some important leaders included Nathaniel Lyon, William Rosecrans, George Henry Thomas, and William Tecumseh Sherman.

- Officer ranks

| Rank group | General/flag officers | Senior officers | Junior officers | Officer cadet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1861–1864 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Major general Commanding the Army |

Major general | Brigadier general | Colonel | Lieutenant colonel | Major | Captain | First lieutenant | Second lieutenant | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1864–1866 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lieutenant general | Major general | Brigadier general | Colonel | Lieutenant colonel | Major | Captain | First lieutenant | Second lieutenant | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Lieutenant General: This rank was created in 1864. Only one person held it, leading all U.S. armies under the President.

- Major General: These generals usually commanded a division. But they often led larger groups like army corps or entire armies.

- Brigadier General: These generals typically commanded a brigade. They were in charge of organizing and managing their units.

- Colonel: A colonel was the commanding officer of a regiment. They oversaw recruitment, training, and daily operations.

- Lieutenant Colonel: This officer was the main assistant to the colonel. They took command if the colonel was absent.

- Major: A major also assisted the colonel and commanded smaller groups of companies.

- Captain: A captain commanded a company. They managed the company's records and trained non-commissioned officers.

- Lieutenant: Lieutenants assisted the captain. They helped with daily tasks, inspections, and leading patrols.

Enlisted Soldiers

Non-commissioned officers (NCOs) were very important for keeping order in the Union Army. They helped soldiers stay in formation during marches and battles. Sergeants were especially key for guiding the troops. NCOs also trained new soldiers.

NCOs were responsible for the regimental colors (flags). These flags helped units stay together and served as a rallying point in battle. A sergeant usually carried the flag, protected by a color guard of corporals.

- Enlisted ranks

| Enlisted Rank Structure | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sergeant Major | Quartermaster Sergeant | Ordnance Sergeant | First Sergeant | Sergeant | Corporal | Musician | Private | |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

No insignia | No insignia | |||

- Sergeant Major: The highest-ranking enlisted soldier in a regiment. They helped the adjutant and oversaw musicians.

- Quartermaster Sergeant: Assisted the regimental quartermaster with supplies and work parties.

- Commissary Sergeant: Assisted with getting and giving out food rations.

- Hospital Steward: Cared for sick and wounded soldiers and managed hospital supplies.

- First Sergeant: The top NCO in a company. They took roll call and managed company supplies.

- Sergeant: Led a squad of soldiers. In battle, they kept soldiers in line and prevented them from running away.

- Corporal: The lowest NCO rank. They led small groups for tasks like guard duty.

- Private: The basic soldier. They performed daily duties, stood guard, and fought in battles. Some had special jobs like cooks or scouts.

Southern Unionists

Some Southerners did not support the Confederacy. They were called Southern Unionists or Union Loyalists. States like Tennessee, Virginia (including West Virginia then), and North Carolina had many Unionists. Many areas in the Appalachian Mountains also supported the Union.

About 100,000 men from Confederate states joined the Union Army or pro-Union groups. Most Southern Unionists were different from the wealthy plantation owners who led the Confederacy.

Different Backgrounds in the Army

About two-thirds of Union soldiers were white Americans born in the U.S. The rest came from many different ethnic groups, including many immigrants. About 25% of white Union soldiers were born in other countries. Many immigrants came to the U.S. in the 1850s, mostly settling in the Northeast.

Germans were the largest immigrant group, with a million arriving between 1850 and 1860. Many Irish immigrants also arrived. Immigrant soldiers were very eager to fight for the Union. They wanted to help their new home and show their loyalty. Generals like Franz Sigel (German) and Michael Corcoran (Irish) were appointed to encourage immigrants to join.

| Estimates | Origin |

|---|---|

| 1,400,000 | Native-born White American |

| 216,000 | Germans/German-American |

| 210,000 | African American |

| 150,000 | Irish-born |

| 18,000 – 50,000 | Canadian |

| 50,000 | English-born |

| 49,000 | Other (Scandinavian, Italian, Jewish, Mexican, Polish, Native American) |

| 40,000 | French/French-Canadian |

Many immigrant soldiers formed their own regiments, like the Irish Brigade or the Gardes de Lafayette. But most foreign-born soldiers were spread out among different units.

The Confederate Army was less diverse. About 91% of its soldiers were white men born in the South. Only 9% were foreign-born white men, mostly Irish.

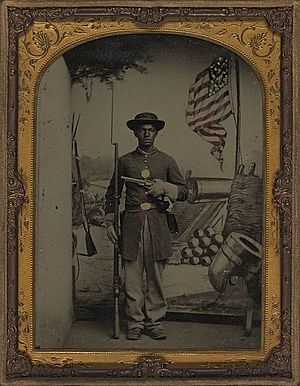

African Americans in the Union Army

By 1860, there were four million enslaved African Americans and half a million free African Americans in the U.S. When the Civil War started, free Black men in the North wanted to join the army. But they were not allowed to at first. Many people doubted Black soldiers could fight well. President Lincoln also worried it would upset white Northerners and the Border States.

However, Lincoln changed his mind. In late 1862, Congress allowed the first official Black enlistment system. This led to the creation of the United States Colored Troops.

Before official enlistment, many Black people volunteered as cooks, nurses, and in other roles. Some states formed their own Black volunteer regiments. The 1st Kansas Colored Infantry Regiment was the first Black regiment to fight in combat. The 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment became famous for its bravery at the Second Battle of Fort Wagner. These efforts showed that Black soldiers could be effective. About 200,000 Black soldiers served in the Union Army.

Even while serving, Black soldiers faced unfair treatment. They were often given less important jobs. Some officers refused to let them fight. Black soldiers were paid less than white soldiers ($10 vs. $16 per month) until June 1864. White officers mostly led Black units. If captured by Confederate forces, Black soldiers risked being enslaved or killed.

Women in the Union Army

Women played many important roles in the Union Army's success. Officially, women were not allowed to be soldiers. But hundreds of women disguised themselves as men to enlist. Many were discovered, but some fought through the entire war without being found out.

Thousands of women, both white and Black, followed the armies. They worked as cooks, laundresses, and nurses. Many were wives or relatives of soldiers. Some women, called vivandières, also helped on the battlefield. They brought water, carried flags, and gave first aid. "Daughters of the regiment" were often officers' daughters who inspired the men. Famous women who helped the armies included Anna Etheridge and Marie Tepe.

Women also wanted to serve as nurses. At first, there was strong resistance. People thought nursing was too hard or improper for women. But Congress eventually allowed women to be nurses. Dorothea Dix became the Superintendent of Army Nurses. Nursing was dangerous work, with long hours and many diseases. Many nurses suffered permanent injuries or died. Despite challenges from male doctors, tens of thousands of women served as nurses. These included Clara Barton, Susie King Taylor, and Louisa May Alcott.

Thousands of women also worked as spies for the Union Army. Early in the war, no one expected women to be spies, which gave them an advantage. They worked as scouts, smugglers, and saboteurs. If caught, female spies usually faced prison, not execution. Many of their identities remain secret. Famous female spies included Harriet Tubman, Pauline Cushman, and Elizabeth Van Lew.

Why Soldiers Fought: Anti-Slavery Feelings

In his book For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War, historian James M. McPherson says Union soldiers fought to save the United States. He also says they fought to end slavery.

McPherson writes that soldiers realized they could not save the Union without also fighting against slavery. Seeing slavery firsthand made many Union soldiers hate it even more. One soldier from Pennsylvania was shocked by a slave woman's story of her husband being whipped. He said, "I thought I had hated slavery as much as possible before I came here, but here, where I can see some of its workings, I am more than ever convinced of the cruelty and inhumanity of the system."

Army Management and Problems

Adjutant General's Department

The Adjutant General's Department (AGD) handled many tasks during the Civil War. Its main job was managing letters and orders between the President, Secretary of War, and the Army. It also managed recruitment, appointed chaplains, kept soldier records, and issued forms.

As the war went on, some of the AGD's jobs were given to new offices. For example, a new Provost Marshal General's Bureau handled recruiting and finding deserters. The AGD also created the Bureau of Colored Troops to manage African American soldiers.

The AGD started with only 14 Regular Officers. But as the Army grew, more officers and civilian staff were added. By 1865, many Volunteer officers also served as assistant adjutant generals. Despite being understaffed, the AGD managed its duties well. It had fewer problems with field commanders than other departments.

Bureau of Military Justice

The U.S. Army had a Judge Advocate office since its beginning. But during the Civil War, Congress officially created the Bureau of Military Justice. This bureau handled military trials and investigations. It also wrote down the laws of war and military laws.

To handle the large army, more judge advocates were appointed. They advised commanders on legal issues and reviewed trial records. In 1863, the bureau was given the power to review appeals.

The bureau successfully handled the many legal issues of the war. It created the Lieber Code, which was a set of rules for soldiers. It also collected all U.S. military laws into one book. One controversial issue was trying civilians in military courts.

Corps of Engineers

The Corps of Engineers was a small but important part of the Army. It ran the West Point academy, which trained officers. Engineers built fortifications, bridges, and roads. They also helped with civil engineering projects like canals.

During battles, engineers built pontoon bridges, repaired roads, dug trenches, and performed scouting. Many important Union officers, like McClellan and Meade, were trained as engineers.

Before the war, the Corps had only 48 officers and one company of 150 engineer troops. During the war, more companies were added, forming a battalion. Congress also added more officers to the Corps. A few Volunteer engineer regiments were formed, but often regular soldiers did engineering work under supervision.

Inspector General's Department

At the start of the Civil War, there was no clear Inspector General's Department. Two Inspector Generals (IGs) checked if the Army was ready. But they worked without a central plan. As the war continued, more IGs were added, and their duties changed often.

In 1863, a permanent IG office was set up in Washington. This helped create standard rules for IGs in the field. Congress also assigned IGs to different army groups.

The inspectorate faced challenges, including commanders who didn't cooperate. But it successfully helped control waste and fraud that was common early in the war.

Medical Department

The Army Medical Department (AMD) was in charge of caring for sick and wounded soldiers. It ran field and general hospitals. It also bought and gave out medicine and medical supplies. Later in the war, the AMD also managed moving wounded soldiers from battlefields and building hospitals.

The AMD also cared for disabled veterans, prisoners of war, and refugees. It kept medical records and prepared a history of the war's medical events. At first, the AMD had old-fashioned leaders, which caused problems. But new leaders helped make important changes.

| Position | 1862 | 1863 | 1864 | 1865 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgeon General (BG) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Assistant Surgeon General (COL) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Medical Inspector General (COL) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Medical Inspector (LTC) | 8 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Surgeon (MAJ) | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Assistant Surgeon (CPT) | 14 | 5 | 3 | |

| Assistant Surgeon (1LT) | 100 | 109 | 111 | 114 |

| Medical Storekeeper | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Medical Cadet | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| Hospital Steward | 201 | 471 | 650 | 931 |

In April 1861, the AMD was the largest staff department. But it was still too small for wartime needs. Congress added more surgeons and medical cadets. In 1862, the AMD was reorganized. Medical inspectors were added to check sanitary conditions. The surgeon general could also hire more hospital stewards.

Most Regular Army medical officers worked in staff jobs. They ran hospitals, supplied medicine, or directed medical care for army units. Thousands of civilian doctors and nurses also worked for the AMD. Private groups like the United States Sanitary Commission (USCC) also helped a lot.

The first Battle of Bull Run showed how unprepared the AMD was. There was no coordination, and some surgeons refused to treat soldiers from other units. But with new leaders, the AMD improved greatly. By the end of the war, it had better ways to move wounded soldiers. It also tested drugs, found reliable supplies, and increased medical staff.

However, some problems remained. Many soldiers died from disease or infection because doctors didn't understand germs. Soldiers also had poor diets. Despite these issues, AMD staff worked hard to help soldiers. They laid the groundwork for better medical care in the future.

Ordnance Department

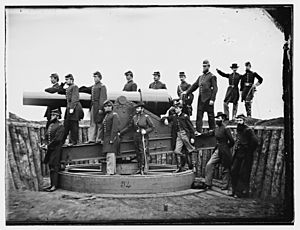

The Ordnance Department (ORDD) was in charge of all Army weapons and related equipment. This included developing, buying, storing, and repairing guns, cannons, and supplies. It also bought horses for artillery until 1861.

The department faced challenges, especially early in the war. It struggled to arm the growing Union Army. Also, Confederate forces seized many arsenals and depots. But the ORDD eventually provided thousands of cannons and millions of small arms for the Union Army.

When the war began, the ORDD was small. It had only 40 officers and a few hundred enlisted men. Most worked at arsenals and depots. Hundreds of civilians, including women and children, also worked there. They were paid less and were thought to be better at assembling cartridges. This work was dangerous, and many died in explosions.

Congress increased the number of ORDD officers and staff during the war. Each regiment had an ordnance officer to manage weapons and ammunition. Higher units also had ordnance officers.

The ORDD had a crisis at the start of the war. Before the war, the Secretary of War had moved many weapons to Southern arsenals. When Southern states seized these, the Union lost many arms. The ORDD had to buy weapons from private companies or Europe. Many of these were low quality or overpriced. But the ORDD eventually controlled the fraud and increased its own production. For example, the Springfield Armory went from making 800 muskets a month to 24,000 by 1863.

The ORDD also faced pressure to adopt new technologies like repeating rifles. The leaders were careful and wanted to test them first. But some of these weapons were bought and given to soldiers.

After the war, the ORDD was criticized for being too slow to adopt new technology. However, it successfully equipped the Union Army with many modern weapons. It produced millions of cannons, small arms, and ammunition.

Pay Department

The Pay Department was responsible for paying Army personnel. This included salaries, allowances, and bonuses. Payments were supposed to happen every two months. But sometimes, they were delayed by many months.

The department was led by a paymaster general and a small number of officers and civilian clerks. Money was sent from the Treasury to paymasters in different army areas. These paymasters then distributed the funds to soldiers. As the Army grew, more paymasters and clerks were needed.

The rapid growth of the Army was a big challenge for the Pay Department. It had to pay over 50 times more soldiers than before the war. It was especially hard to find and pay sick or wounded soldiers. However, payments were rarely delayed so much that soldiers rebelled. The Pay Department paid out over $1 billion during the war.

Provost Marshal General's Bureau

The Provost Marshal General's Bureau (PMGB) was created to catch deserters, conduct spy-catching, and get back stolen government property. It started in 1862 and became an independent department in 1863. It also managed the draft system. Later, it managed the Invalid Corps (soldiers who couldn't fight but could do other jobs) and recruited white volunteers. The PMGB was a temporary organization and closed in 1866.

The bureau grew to include many officers and employees. Each area of Congress had a provost marshal who oversaw the draft. Special agents were also appointed to catch deserters. All provost marshals could arrest soldiers who were away without leave.

Overall, the PMGB successfully enrolled enough men for the Union Army. It also caught over 76,500 deserters and returned them to duty.

Quartermaster's Department

The Quartermaster's Department (QMD) was the largest and most important department in the Union Army. It provided transportation for the entire Army. It also bought, stored, and distributed many supplies. These included clothing, tents, horses, mules, fuel, and vehicles like wagons and ambulances.

The QMD also built and maintained military buildings like barracks and hospitals. It managed all Army ships and military railroads. It also handled wagon trains, buried the dead, and maintained national cemeteries.

At the start of the war, the QMD was very small. But Congress quickly increased its size. Hundreds of Volunteer officers were commissioned as assistant quartermasters. Many civilian workers were also hired, including women. By 1864, the QMD relied heavily on Black workers for many jobs.

QMD officers commanded supply depots or worked with army units. Depots bought supplies from companies or made them. Supplies were then shipped to advanced depots and given to units.

The main QMD depots were in major cities like New York, Philadelphia, and St. Louis. Many temporary depots were also set up closer to the fighting.

In the early war, the QMD struggled to equip the growing army. There was a lot of fraud and political interference. But under the leadership of Quartermaster-General Montgomery C. Meigs, this corruption was controlled. Most quartermasters were honest and capable. The Union Army rarely ran out of supplies. The QMD also used new technologies like railroads and steamboats to move supplies efficiently.

The QMD spent over $1 billion during the war. It acquired millions of horses and mules, moved over 1.2 million troops by rail, and managed thousands of ships and wagons. It also bought huge amounts of food, fuel, and other supplies.

Signal Corps

The Signal Corps was created thanks to Albert J. Myer, an Army surgeon. He developed a system of military signals using flags, called wigwag. Myer was appointed to lead the Signal Corps in 1860.

Early in the war, the Signal Corps only had Myer as an officer. Other soldiers were sent to learn his system and teach it to others. Myer pushed for a more formal Signal Corps, which Congress approved in 1863.

The Signal Corps was very important for coordinating Union Army actions. It helped send messages quickly across battlefields. After the war, Myer was again appointed to lead it.

Subsistence Department

The Subsistence Department was responsible for buying, storing, and distributing food rations to soldiers. It was the smallest of the supply departments. Even as the army grew to over a million soldiers, the department itself did not expand much. Yet, it successfully fed the Army. President Lincoln once said it was like a "well-regulated stomach" because it worked so smoothly.

The department's strength at the start of the war was small. It had a Commissary General of Subsistence (CGS) and a few other officers. They worked at the main office or managed supply depots. There were no enlisted soldiers in the department, but civilian clerks and laborers helped.

To feed the growing army, Congress added more officers to the department. Many Volunteer officers also filled commissary roles. They learned their duties over time.

The main food depots were in cities like Baltimore, Chicago, and Philadelphia. These depots received large food shipments and repackaged them for the armies. The Quartermaster Department handled the actual transportation of food. The Subsistence Department also set up mobile beef herds that followed the armies.

Secretary Stanton noted the department's success. He said no Union Army operation failed because of a lack of food. The department bought over $361 million in food and supplies during the war. This included huge amounts of hardtack, bacon, sugar, coffee, and live cattle.

Military Fighting Methods

The Union Army's fighting methods were based on older European traditions. Soldiers marched close together in lines or columns. They would fire their muskets at the enemy. A big change was the widespread use of rifled muskets. These guns could shoot accurately up to 500 yards, much farther than older muskets.

In an attack, artillery and skirmishers would fire first. Commanders preferred to attack from the side (flanking maneuver) if possible. If not, a direct frontal assault was made. Infantry lines would advance, then charge the enemy's position. If successful, they would regroup and continue the attack.

Defensive earthworks were used a lot. Soldiers built rifle pits, abatises (fallen trees), and palisades (wooden fences). Large trench systems were built, often with the help of Black laborers. If no fortifications were available, soldiers would defend strong natural features like stone walls.

Union cavalry were not used much in big battles early in the war. They mostly went on scouting and raiding missions. But under leaders like Philip Sheridan, Union cavalry developed new tactics. Instead of just charging, some troopers would dismount and fight on foot. They used repeating firearms, which gave them an advantage. If fighting on foot didn't work, they would remount and attack from another direction. This allowed them to defeat enemy units one by one.

Desertions and Draft Riots

Desertion was a big problem for both sides. Soldiers left for many reasons: the hard life of war, long marches, thirst, heat, disease, delayed pay, worry for their families, boredom, fear before battle, and losing confidence in their leaders.

In 1861 and 1862, the Union Army faced many defeats. There were about 180,000 desertions. In 1863 and 1864, the worst years of the war, about 200 soldiers deserted every day. This meant about 150,000 desertions in those two years. The total number of desertions for the Union Army during the war was around 350,000. This means about 15% of Union soldiers deserted. Official numbers are lower, around 200,000. Many historians believe the true rate was between 9% and 12%. About one-third of deserters returned to their units. Some were "bounty jumpers" who joined to get a cash bonus, then deserted to do it again elsewhere.

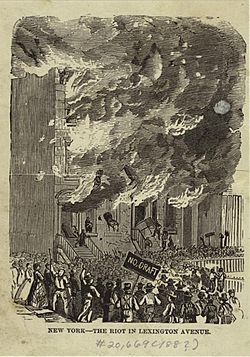

Irish immigrants were the main group in the famous "New York Draft riots" of 1863. Some Democratic politicians stirred them up. The Irish had opposed the war and the freeing of slaves. They worried that freed Black people would compete for jobs and lower wages. They felt the draft was unfair because rich men could pay to avoid serving.

The riots began in July 1863, during the Battle of Gettysburg. Mobs, mostly Irish immigrants, attacked African American churches, the Colored Orphan Asylum, and homes of anti-slavery activists. The Union Army had to be sent in after the victory at Gettysburg. Some units had to open fire to stop the violence. Up to 1,000 people were killed or wounded. There were also smaller riots in other Northern areas.

|

See also

In Spanish: Ejército de la Unión para niños

In Spanish: Ejército de la Unión para niños

|

|

|

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |