History of Denver facts for kids

This article is about the history of the City and County of Denver, Colorado, from its start in 1858 to today. From the time of the gold rush, Denver has been the biggest and most important city in Colorado. Because it's located where the Great Plains meet the Rocky Mountains, Denver has always connected different parts of the state. As the state capital, it has been the center for making important decisions.

The 1800s: A City is Born

Gold Rush and First Towns

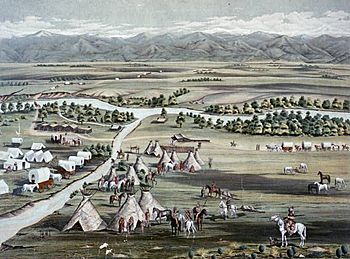

Until the late 1850s, not many people lived in the Denver area, which was then part of the Territory of Kansas. In July 1858, a man named Green Russell found a small amount of gold near a stream. This was the first major gold discovery in the Rocky Mountain region.

News of the gold spread fast. By the spring of 1859, thousands of people rushed to the area, hoping to get rich. This was called the Pike's Peak Gold Rush. In the next two years, about 100,000 people came to the region.

In 1858, a group from Lawrence, Kansas, started a town called Montana City. It was the first town in the area that would become Denver. But when miners didn't find much gold there, they moved and started a new town called St. Charles.

Soon after, another town called Auraria was founded on the other side of Cherry Creek. It was started by Green Russell and other settlers. They gave away land to anyone who would build a house and live there. A third town, Highland, was also started, but it grew slowly because it was separated by the river.

General Larimer and Denver City

In November 1858, a land speculator named General William Larimer arrived. He and his group took over the St. Charles townsite and renamed it "Denver City." They named it after James W. Denver, the governor of the Kansas Territory, hoping he would make it the county seat. But by the time they named it, Governor Denver had already left his job.

At first, Denver was a place where people searched for gold in the streams. But the gold in the streams ran out quickly. When much richer gold deposits were found in the mountains, it seemed like Denver might be abandoned. However, the new mines needed supplies, and Denver became the main hub for providing food, tools, and other goods to the miners. This helped the city survive and grow.

Colorado Becomes a Territory

The Denver area was part of Arapahoe County in the Kansas Territory, but the government in Kansas was far away and busy with its own problems. The settlers in the goldfields decided they needed their own government.

In 1859, they created the Territory of Jefferson, but the U.S. Congress did not approve it. Finally, on February 28, 1861, President James Buchanan signed a law creating the Territory of Colorado. The first governor, William Gilpin, arrived in Denver that May. The new government created 17 counties, including a new Arapahoe County with Denver City as its county seat.

In 1867, Denver City became the capital of the Colorado Territory. It shortened its name to just "Denver." When Colorado became a state in 1876, Denver became the state capital.

A Decade of Challenges

The 1860s were a difficult time for Denver. When the American Civil War began, most people in Denver supported the Union. Colorado sent soldiers to fight against the Confederates. With money and resources going to the war, Denver's growth slowed down.

The city also faced other disasters. In 1863, a large fire destroyed many of the city's wooden buildings. After the fire, a new law required buildings in the downtown area to be made of brick, which made the city safer.

A year later, in 1864, heavy rains and melting snow caused Cherry Creek to flood. The flood destroyed many buildings and homes. Despite these challenges, the people of Denver rebuilt their city each time.

The Railroad Changes Everything

After the Civil War, Denver's leaders knew that the city needed a railroad to grow. When the main transcontinental railroad was built through Wyoming instead of Colorado, many people worried Denver would be left behind.

Governor John Evans and other business leaders decided to build their own railroad to connect Denver to the main line in Wyoming. They formed the Denver Pacific Railway. The first train arrived in Denver in June 1870. Two months later, another railroad, the Kansas Pacific, connected Denver to the east.

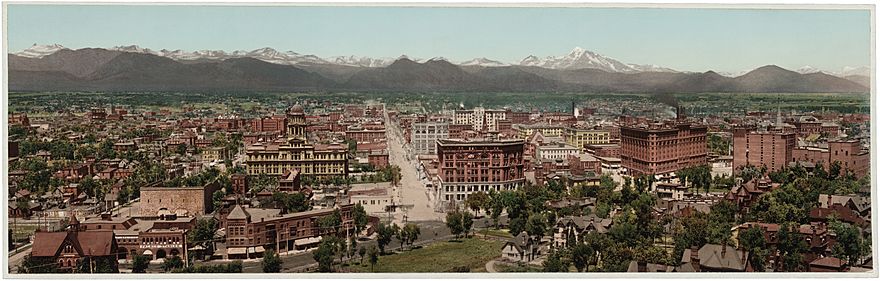

The railroads were a huge success. They brought new people, tourists, and supplies to Denver every day. The city's population grew very quickly, from about 4,700 in 1870 to over 35,000 in 1880. The railroad helped Denver become the most important city in the region.

The Silver Boom

In the 1870s and 1880s, large amounts of silver were discovered in the Colorado mountains. This brought a lot of wealth to Denver. The city's economy grew stronger with businesses in manufacturing, food processing, and trade. By 1890, Denver was the 26th largest city in America.

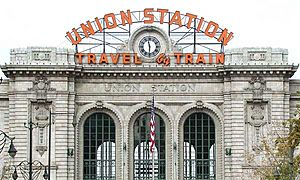

This new wealth led to the construction of many beautiful buildings. The Tabor Grand Opera House, built in 1881, was one of the fanciest theaters in the West. Other grand buildings included Union Station (1881), the Brown Palace Hotel (1892), and the Colorado State Capitol Building (1894).

During this time, some people in the city were not always honest, and there were problems with crime. But there were also many people working to make the city better. Women fought for and won the right to vote in 1893. Church groups and charities started organizations to help the poor and sick. Because of its dry climate, Colorado also became known as "The World's Sanatorium," a place where people with breathing problems, like tuberculosis, came to get well.

Economic Panic and Self-Governance

In 1893, a national financial crisis called the Panic of 1893 caused the price of silver to crash. Mines closed, banks failed, and many people lost their jobs and savings. Unemployed miners from the mountains came to Denver looking for work, but there were few jobs to be found. The city's population shrank for a few years.

At the time, the state government had a lot of control over how Denver was run. The people of Denver wanted more say in their own government. This led to a "home rule" movement. In 1902, an amendment to the state constitution was passed that allowed Denver to become a consolidated city–county, giving it more control over its own affairs.

The 1900s: A Modern City Emerges

The Progressive Era

The early 20th century was a time of progress and reform in Denver. In 1904, Mayor Robert W. Speer started projects to beautify the city. This included building the Civic Center and the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.

During this time, Denver also created one of the first juvenile courts in the country, led by Judge Ben Lindsey. This was a new way of treating children in the legal system. In 1914, a teacher named Emily Griffith opened the Opportunity School to provide job training and classes for adults.

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Denver supported the war effort. After the war, some groups like the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) became powerful for a short time. The KKK was a group that was unfair to immigrants, Catholics, and Jewish people. However, their influence faded as more people in Colorado rejected their ideas.

The Great Depression and a Slow Recovery

The 1920s were a difficult time for Colorado's mining and farming industries. Then, in 1929, the U.S. economy crashed, leading to the Great Depression. At the same time, a long drought turned the plains into the "Dust Bowl." Many people lost their jobs and homes.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt's "New Deal" programs helped bring jobs and money to Denver. The government hired people to build roads, parks, and schools. Artists were paid to create murals and sculptures for public buildings.

Transportation also improved. The Moffat Tunnel, completed in 1928, created a shorter railroad route through the Rocky Mountains. Denver's airport opened in 1929, and as airplanes improved, the city became a hub for air travel.

World War II and Post-War Growth

World War II helped pull Denver out of the Great Depression. The city became home to military bases and factories that supported the war. The federal government built the Rocky Mountain Arsenal and the Denver Ordnance Plant. Many federal agencies also opened offices in Denver.

After the war, many of these facilities remained. The Denver Ordnance Plant became the Denver Federal Center. The growth of government jobs attracted other industries, especially aerospace companies like Lockheed-Martin.

From 1953 to 1989, the Rocky Flats Plant, a nuclear facility near Denver, made parts for the nation's defense program. However, a fire and leaks at the plant caused radioactive pollution in some areas, which raised health concerns for people living nearby.

The city's population grew rapidly after the war. Many families moved to new suburbs outside the city. During this time, many of Denver's historic Victorian buildings were torn down. This led citizens to create groups to protect the city's historic architecture.

Downtown Boom and Suburban Growth

In the 1970s, an energy crisis caused the price of oil to rise. Because Colorado has large energy fields, many oil and gas companies opened offices in Denver. This led to a boom in the construction of skyscrapers downtown.

As more people moved to the suburbs, traffic and air pollution became serious problems. A brown cloud of smog often hung over the city. In 1974, the Regional Transportation District (RTD) was created to improve public transit.

In the 1980s, oil prices fell, and Denver's economy slowed down again. Many people lost their jobs, and office buildings downtown sat empty.

New Growth and Big Projects

In 1983, Federico Peña was elected as Denver's first Hispanic mayor. He led the city through the tough economic times and convinced voters to invest in major projects. These included a new airport, the Colorado Convention Center, and a new baseball stadium, Coors Field.

In 1991, Wellington Webb became the city's first African American mayor. He continued to support downtown development and neighborhood improvements.

The biggest project was Denver International Airport (DIA), which opened in 1995. The old airport, Stapleton, was surrounded by the city and had no room to grow. DIA was built on a huge piece of land and helped Denver become a major national and international travel hub.

By the end of the 1990s, Denver's economy was strong again. The city had cleaned up its air, and the historic "Lower Downtown" (LoDo) area was revitalized with new restaurants, shops, and apartments.

The 21st Century

In the 2000s, Denver continued to grow. To deal with traffic, the RTD expanded its light rail system with major projects like T-REX and FasTracks. These projects built new rail lines connecting downtown to the suburbs.

Denver's economy also became more diverse. Instead of relying only on energy and government jobs, the city developed strong industries in healthcare, technology, and tourism. This helped Denver handle the 2008 economic recession better than many other cities.

In 2011, Michael Hancock was elected as Denver's second African American mayor, and he served until 2023. Today, Denver is a vibrant and growing city, known for its beautiful mountain views, outdoor activities, and thriving culture.

See also

- Timeline of Denver

- Outline of Colorado

- Index of Colorado-related articles

- Historic Colorado counties

- Arapahoe County, Kansas Territory

- Arrappahoe County, Jefferson Territory

- Arapahoe County, Colorado Territory

- List of mayors of Denver

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Denver, Colorado

- Pike's Peak Gold Rush