History of Sussex facts for kids

| Sussex | |

| Motto: We wunt be druv | |

|

|

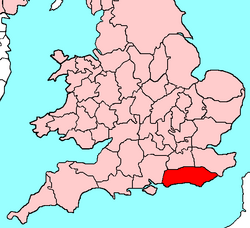

Ancient extent of Sussex |

|

| Geography | |

| Status | Ceremonial county (until 1974) |

| 1831 area | 907,920 acres (3,674 km2) |

| 1901 area | 932,409 acres (3,773 km2) |

| HQ | Chichester or Lewes |

| Chapman code | SSX |

| History | |

| Origin | Kingdom of Sussex |

| Created | In antiquity |

| Succeeded by | East Sussex and West Sussex |

Quick facts for kids Demography |

|

|---|---|

| 1831 population - 1831 density |

272,340 0.3 per acre (74/km2) |

| 1901 population - 1901 density |

602,255 0.6 per acre (150/km2) |

Sussex comes from the Old English words 'Sūþsēaxe'. This means 'South Saxons'. It is a historic county located in South East England.

People have lived in Sussex for at least 500,000 years. This is known from a fossil called Boxgrove Man. It is believed to be the oldest human fossil found in Britain. Tools found near Pulborough are about 35,000 years old. These tools might be from the last Neanderthals or early modern humans.

Ancient flint mines from around 4000 BC are on the South Downs. These are some of the oldest in Europe. Sussex also has many remains from the Bronze Age and Iron Age. Before the Romans arrived, a tribe called the Belgic tribe lived here. Their leader, Togibubnus, ruled much of Sussex.

When the Romans left in the 5th century, people from Germany arrived. They created the kingdom of the South Saxons. King Ælle was their ruler. He was known as the first 'Britain ruler' or bretwalda.

Sussex was the last of the seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms to become Christian. This happened under St Wilfrid. By the 8th century, the kingdom had grown. Around 827, Sussex became part of the kingdom of Wessex. This kingdom later grew into the kingdom of England.

In 1066, Norman forces arrived in Sussex. King Harold Godwinson's army was defeated at the Battle of Hastings. After this, William the Conqueror created six special areas called rapes. The main church in Sussex moved from Selsey Abbey to Chichester. Many castles were built and often attacked during the Middle Ages.

Sussex was important because it was on the direct route between England and Normandy. Many ports, including the Cinque Ports, provided ships for battles. The Hundred Years' War made Sussex a frontline area. Later, there were rebellions like the Peasants' Revolt and Jack Cade's rebellion.

Under Henry VIII, the Church in England separated from the Roman Catholic Church. When Mary I became queen, England returned to Catholicism. In Sussex, 41 Protestants were executed for their beliefs. Under Elizabeth I, some Catholics also lost their lives.

Sussex mostly avoided the worst parts of the English Civil War. There were two sieges and one battle. As the Industrial Revolution began, the Wealden iron industry declined. Seaside resorts became popular in Sussex in the 18th century.

Sussex soldiers played a big part in World War I. The Battle of the Boar's Head was a very difficult battle for them. In World War II, Sussex was a base for the Dieppe Raid and D-Day landings. In 1974, Sussex was divided into East and West Sussex. These became separate ceremonial counties.

In recent times, Sussex Day and a county flag were created for Sussex. A National Park was also set up for the South Downs.

Contents

- Exploring Ancient Sussex: From Stone Age to Iron Age

- Roman Influence in Sussex

- Saxon Sussex: The Kingdom of the South Saxons

- Norman Sussex: Changes After the Conquest

- Sussex in the Middle Ages: Wars and Rebellions

- Early Modern Sussex: Religious Changes and Civil War

- Modern Sussex: From Seaside Resorts to World Wars

- How Sussex Was Governed: From Hundreds to Modern Councils

- Inheritance Customs in Sussex

- Religion in Sussex Through History

- Parliamentary History of Sussex

- Rebellions, Riots, and Unrest in Sussex

- Wars and Defenses in Sussex

- Industries of Sussex: From Ancient Times to Today

- Transportation in Sussex: Roads, Canals, and Railways

- Images for kids

Exploring Ancient Sussex: From Stone Age to Iron Age

Stone Age Discoveries in Sussex

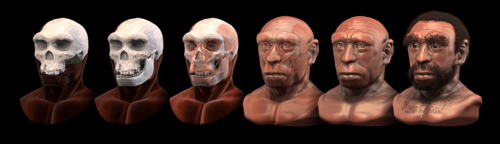

In 1993, a human leg bone was found at Boxgrove near Chichester. Then in 1996, two human teeth were found there. These remains became known as "Boxgrove man". They are thought to be from a species called Homo heidelbergensis.

Boxgrove man lived during a warm period. This was between 524,000 and 478,000 years ago. This time is known as the Lower Paleolithic period.

In 1900, old flint tools were found at Beedings. More tools were found there in 2007–08. These tools are from the Early Upper Paleolithic period. They help us understand late Neanderthals and early modern humans in northern Europe.

During the Mesolithic Age (around 8000 BC), hunters came to Sussex from Europe. Britain was still connected to Europe then. But melting ice caused sea levels to rise. This formed the Straits of Dover, cutting off Britain.

Archaeological finds from these people are mostly in the central Wealden area. Many knives, scrapers, and arrowheads have been found.

Near the River Ouse, polished axes and other Neolithic flint tools were found. This suggests that some land was cleared in the river valley.

From about 4300 BC to 3400 BC, flint mining was very important. Flint was used locally and traded widely. There was also a pottery industry in Neolithic Sussex.

Bronze Age Life in Sussex

The Early Bronze Age in Sussex began with the arrival of Beaker pottery. Several finds have been made, including a settlement near Beachy Head in 1909. Pottery, flints, and other items were found there.

The presence of Beaker pottery shows that people migrated from northern Europe. Recent DNA analysis confirms that British Beaker people were related to those from central Europe.

From the Bronze Age (about 1400-1100 BC), settlements and burial sites can be found across Sussex.

Iron Age Communities in Sussex

Over fifty Iron Age sites are known across the Sussex Downs. Cissbury Ring is one of the most famous hill-forts.

Archaeologists have excavated several farmsteads. These show that the economy was based on mixed farming. Iron tools like ploughshares and sickles were found. Animal bones, especially from cattle and sheep, show they raised livestock. Items found also show they spun and wove wool. People in Iron Age Sussex also ate shellfish from the sea.

Towards the end of the Iron Age (around 75 BC), the Atrebates tribe invaded southern Britain. They were a mix of Celtic and German people. This was followed by a temporary Roman invasion under Julius Caesar in 55 BC.

Soon after, the Celtic Regnenses tribe, led by Commius, occupied the Manhood Peninsula. Tincomarus and then Cogidubnus followed Commius as rulers. At the time of the Roman conquest in AD 43, there was a large settlement in the Selsey region.

Roman Influence in Sussex

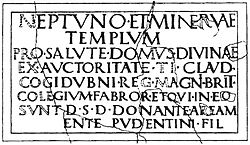

After the Roman invasion, Cogidubnus was made ruler of the Regnenses. He took the name Tiberius Claudius Cogidubnus. He claimed to be 'great king of Britain'. His name is on two early Roman inscriptions in his capital, Noviomagus Reginorum (Chichester).

Many Roman remains have been found in Sussex. These include coin hoards and decorated pottery.

Examples of Roman roads include:

Important Roman buildings found are:

The Roman coast had defensive forts. Towards the end of Roman rule, the coast was attacked by Saxons. More forts were built against this threat. Anderitum (Pevensey Castle) is an example in Sussex. These defenses were managed by the Count of the Saxon Shore. Some believe Romans hired German soldiers to defend the coast. These soldiers might have stayed and mixed with later Anglo-Saxon invaders.

Saxon Sussex: The Kingdom of the South Saxons

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says the Kingdom of Sussex began in AD 477. It states that Ælle arrived at Cymenshore with his three sons. They fought the local people.

Most historians think this founding story is a myth. However, archaeology shows Saxons did settle here in the late 5th century. The Kingdom of Sussex later became the county of Sussex. After Christianity arrived, the church in Selsey moved to Chichester in the 11th century. The church area, called a 'see', matched the county borders. In the 12th century, it was split into two parts, Chichester and Lewes.

Norman Sussex: Changes After the Conquest

On October 13, 1066, Harold Godwinson and his English army arrived at Senlac Hill. They were there to face William of Normandy and his invading army. On October 14, 1066, Harold was killed in the Battle of Hastings. The English army was defeated. Most fighting men from Sussex were likely at this battle. Many lost their lives, and their lands were taken by the Normans.

William built Battle Abbey at the battle site. The spot where Harold fell was marked by the main altar. Norman influence was already strong in Sussex before the Conquest. For example, the abbey of Fécamp had interests in Hastings, Rye, Winchelsea, and Steyning. After the Norman conquest, 387 Saxon-owned estates were given to just 16 new Norman lords.

The 16 new manor owners were called Tenentes in capite. This means they held their land directly from the king. Nine of these were church leaders. Two were English lords who kept their land. This means 353 of the 387 manors in Sussex were taken from Saxon owners. They were given to Norman lords by William the Conqueror.

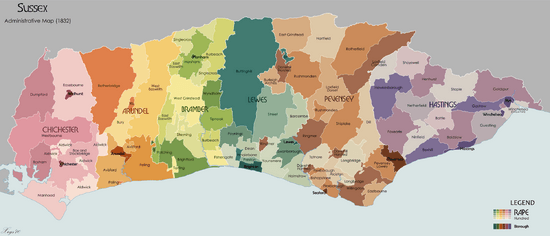

Sussex was very important to the Normans. Hastings and Pevensey were on the most direct route to Normandy. Because of this, the county was divided into five new areas called rapes. Each rape had at least one town and a castle. This helped the Normans control the land and its wealth.

William the Conqueror gave these rapes to his most trusted barons:

- Roger of Montgomery received Chichester and Arundel.

- William de Braose received Rape of Bramber.

- William de Warenne received Rape of Lewes.

- Robert, Count of Mortain received Rape of Pevensey.

- Robert, Count of Eu received Rape of Hastings.

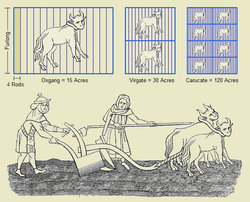

Before, Saxon lords had scattered land. Now, the lords' lands were set by the rape borders. A unit of land called a hide in Sussex had eight virgates. A virgate was the amount of land two oxen could plough in a season.

The northern border of Sussex was long and unclear. This was due to the thick Andredsweald forest. Even in 1834, parts of Sussex were still considered part of Hampshire.

Sussex in the Middle Ages: Wars and Rebellions

During the Hundred Years' War, Sussex was a key area. It was easy for French attacks and English counter-attacks. Hastings, Rye, and Winchelsea were all burned during this time. These towns became part of the Cinque Ports. This was a group of towns that provided ships for England's defense. Also, Amberley and Bodiam castles were built to protect rivers.

Early Modern Sussex: Religious Changes and Civil War

Like the rest of England, Sussex felt the impact of the Church of England's split from Rome. This happened during the reign of Henry VIII. In 1538, a royal order removed the shrine of Saint Richard in Chichester Cathedral.

When Queen Mary became queen, 41 people in Sussex were executed for their Protestant beliefs. Under Elizabeth I, religious differences continued. Several Catholics were executed for their faith.

Sussex largely avoided the worst parts of the English Civil War. In 1642, there were sieges at Arundel and Chichester. A small fight happened near Haywards Heath. Royalists marching towards Lewes were stopped by Parliamentarians. The Royalists were defeated.

Even though Parliament controlled Sussex, Charles II escaped capture here. He traveled through the county after the Battle of Worcester in 1651. He then escaped to France from Shoreham port.

Modern Sussex: From Seaside Resorts to World Wars

The Sussex women are very nice in their dress and in their houses. The men and boys wear smock-frocks more than they do in some counties. - William Cobbett. 1822

The Sussex coast changed a lot in the 18th century. Sea bathing became popular for health among wealthy people. Resorts like Brighton, Hastings, Worthing, and Bognor grew.

In the early 19th century, farm workers faced hard times. Many lost their jobs, and wages dropped. Conditions were so bad that some workers died of starvation. This led to riots, first in Kent, then in Sussex. These riots, known as the Swing Riots, lasted for weeks.

During World War I, on June 30, 1916, the Royal Sussex Regiment fought in the Battle of the Boar's Head. This day became known as The Day Sussex Died. In less than five hours, 17 officers and 349 men were killed. Another 1,000 men were wounded or captured.

When World War II began, Sussex was on the frontline. Its airfields were vital in the Battle of Britain. Many towns were bombed often. While Sussex regiments fought overseas, the Home Guard defended the county. They were helped by the First Canadian Army.

Before the D-Day landings, Sussex saw a huge build-up of soldiers and equipment. Landing crafts were assembled, and Mulberry harbours were built off the coast. In 1974, Sussex was divided into East and West Sussex. These became separate ceremonial counties.

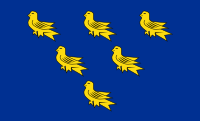

Today, many organizations still operate across the historic Sussex borders. These include the Diocese of Chichester and Sussex Police. In 2007, Sussex Day was created to celebrate the county's history. The Flag of Sussex, with its six gold martlets, was recognized in 2011. In 2013, the government officially recognized England's 39 historic counties, including Sussex.

How Sussex Was Governed: From Hundreds to Modern Councils

The system of hundreds was introduced by the Saxons. In the 7th century, Sussex had about 7,000 families or 'hides' (units of land). The Normans' creation of 'rapes' divided some of these hundreds. Sussex ended up with six rapes: Chichester, Arundel, Bramber, Lewes, Pevensey, and Hastings.

At the time of the Domesday Survey, Sussex had 59 hundreds. This later grew to 63. Most of these kept their original names. The names changed if the meeting place of the hundred court moved. These courts were often controlled by the Church or powerful lords.

Separate from the hundreds were the boroughs.

The county court was held at Lewes and Shoreham until 1086. Then it moved to Chichester. In 1504, it was decided the court would be held alternately at Lewes and Chichester.

A county prison was built in Chichester Castle around 1107–1109. The castle was later demolished, and a new prison was built on the same site. By 1269, this prison was given to the Greyfriars to build a priory. From 1242, Sussex and Surrey shared prison space. Sussex men were sometimes held in Guildford prison.

Due to overcrowding during the Peasants' Revolt in 1381, the Earl of Arundel had to use his castles as prisons. Sussex got a county prison again in Lewes in 1487. It later moved to Horsham in 1541 for a time.

In the mid-16th century, court sessions were usually held at Horsham or East Grinstead. A new prison was built in Horsham in 1775. Another prison, the Petworth House of Correction, was built in Petworth in 1788. More Houses of Correction were built in Lewes and Battle.

The last known case of someone being executed by being pressed to death (peine forte et dure) in England happened in Horsham in 1735. The last public hanging in Sussex was in Horsham in 1844. The prison there closed a year later.

The sheriff was responsible for civil justice in the county. Surrey and Sussex shared one sheriff until 1567. They shared again from 1571 to 1636, when each county got its own sheriff. The role of High Sheriff for Sussex ended in 1974. This was due to the local government changes that split Sussex into two counties.

During times of trouble, the monarch would appoint a 'lieutenant' for the county. This became a permanent role under Henry VIII. The first Lord Lieutenant of Sussex was Sir Richard Sackville in 1550. Their main duty was to oversee the military, like the Militia and the Sussex Yeomanry.

Like the Sheriff, the Lord Lieutenant of Sussex role ended in 1974. Now, East and West Sussex have separate Sheriffs and Lords Lieutenant. Their roles today are mostly ceremonial.

Private legal areas, both church-owned and lay, were important. The main church ones belonged to the Archbishop of Canterbury, the bishop of Chichester, and Battle Abbey. The main lay ones were the Cinque Ports and the Honour of Pevensey. The Cinque Ports were coastal towns with special rights. They were exempt from taxes and could enforce laws. In return, they provided ships and men for the king in wartime.

An 'honour' was a collection of lands held directly from the Crown. The Honour of Pevensey was also known as the Lordship of Pevensey Castle. It was sometimes called the Honour of The Eagle. This name came from the lords of L'Aigle, a town in Normandy.

Inheritance Customs in Sussex

Borough-English was a custom where land passed to the youngest son or daughter. If there were no children, it went to the youngest brother. This name came from a case in Nottingham in 1327. In Sussex, this custom was still found on 134 manors after 1750.

Gavelkind was a practice of equal inheritance, not just to the eldest. It was common in Kent but also found in Sussex. It existed in Rye, Brede, and Coustard manor. Both Borough-English and gavelkind were finally ended in England and Wales in 1925.

Religion in Sussex Through History

Before Christianity, people in Sussex practiced several religions. These included Celtic polytheism and Roman religion. Christianity was present during the Roman-British period. But it was replaced by the polytheistic religion of the South Saxons in the 5th century. According to Bede, Sussex was the last area in England to become Christian.

After a church meeting in London in 1075, church centers were moved to cities. So, the South Saxon diocese moved from Selsey to Chichester.

Like the rest of England, Sussex felt the split of the Church of England from Rome. This happened during Henry VIII's reign. After 20 years of religious reform, the Catholic Mary Tudor became queen in 1553. Mary's actions against Protestants earned her the nickname Bloody Mary. About 288 Protestants were executed in England during her reign. This included 41 in Sussex, mostly in Lewes.

In 1851, a census of places of worship was taken. In Sussex, there were more Anglican churches than non-conformist ones. In nearby counties like Hampshire and Kent, there were more non-conformist places.

Parliamentary History of Sussex

The Parliamentary history of Sussex began in the 13th century. In 1290, Henry Hussey and William de Etchingham were the first elected representatives.

By 1801, Members of Parliament (MPs) from southern coastal counties held a third of all seats. But they represented only about 15% of the country's population. The election system had not changed much since 1295. Each county elected two MPs. Each town with a Royal charter also elected two MPs. This meant large industrial towns in the north had no representation. But smaller southern towns, important in medieval times, still had two MPs.

Many wanted to reform the system from 1770 onwards. Finally, in 1830, the Reform Act 1832 was introduced. This gave large industrial towns in the north their first MPs. Smaller English towns, called Rotten Boroughs, lost their MPs. In Sussex, these included Bramber, East Grinstead, Seaford, Steyning, and Winchelsea.

The Representation of the People Act 1884 and the Redistribution of Seats Act 1885 further changed the system. They redistributed 160 seats and expanded voting rights.

After the 1832 Reform Act, Sussex was divided into eastern and western parts. Each part elected two representatives. In June 1832, C.C. Cavendish and H.B. Curteis were elected for the eastern part. The Earl of Surrey and Lord John George Lennox were elected for the western part.

Before 1832, towns like Arundel, Chichester, Hastings, Horsham, Lewes, Midhurst, New Shoreham, and Rye each elected two members. Arundel, Horsham, Midhurst, and Rye lost one member in 1832. Chichester and Lewes lost one in 1867, and Hastings in 1885. Arundel lost all its members in 1868. Chichester, Horsham, Midhurst, New Shoreham, and Rye lost all their members in 1885.

The new system based constituencies on population numbers, not historic towns. The 19th-century reforms made the election system fairer. But it was not until 1928 that all men and women over 21 could vote.

Rebellions, Riots, and Unrest in Sussex

Sussex, because of its location, was often involved in invasions and rebellions.

In 1264, a civil war broke out in England. It was between barons led by Simon de Montfort and royal forces led by Prince Edward. This was known as the Second Barons' War. On May 12, 1264, Simon de Montfort's forces took over 'Offam Hill' near Lewes. Royalist forces tried to attack but were defeated. The Battle of Lewes was fought fiercely for over five hours. In the 19th century, road builders found mass graves with about 2000 bodies from the battle.

During the Middle Ages, peasants in the Weald rebelled twice. First, in the Peasants' Revolt in 1381, led by Wat Tyler. Second, in Jack Cade's rebellion of 1450. Cade's rebellion had support from many people, not just peasants. Even gentlemen, craftspeople, and the Abbot of Battle joined him. Jack Cade was fatally wounded in a fight at Heathfield in 1450.

During the English Civil War, Sussex was divided. Arundel supported the king, while Chichester, Lewes, and the Cinque Ports supported Parliament. Most of the west of the county was for the king. However, a group of royalists led by Edward Ford captured Chichester for the king in 1642. They imprisoned 200 Parliament supporters.

The roundhead army, led by Sir William Waller, besieged Arundel. After taking Arundel, they marched on Chichester and returned it to Parliament. Chichester was then demilitarized in 1647–1648. It remained under Parliament's control for the rest of the war. William Cawley, a brewer, became an MP for Chichester in 1647. He was one of the people who signed King Charles I's death warrant.

In the early 19th century, farm workers faced worsening conditions. More became unemployed, and wages were forced down. In 1830, it was reported that four harvest workers had died of starvation. This led to riots in Kent, which spread to Sussex. These Swing Riots lasted for weeks, continuing until 1832.

The Swing riots involved actions against farmers and landowners. Threatening letters, signed by a mythical Captain Swing, demanded that machines like threshing machines be removed. They also demanded higher wages. If demands were not met, farm equipment was destroyed, and sometimes arson occurred.

The army was called in to control the situation in eastern Sussex. In the west, the Duke of Richmond used the yeomanry and special police against protesters. The Sussex Yeomanry were nicknamed the workhouse guards. Protesters faced charges like arson, robbery, and riot. Those convicted faced imprisonment, transportation, or execution.

These grievances led to a wider demand for political reform. This resulted in the Reform Act of 1832. One main complaint of the Swing protesters was about poor benefits. Sussex had the highest poor-relief costs from 1815 to the 1830s. Its workhouses were full. The unrest helped bring about the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834.

Wars and Defenses in Sussex

During the French revolutionary and Napoleonic wars (1793–1815), Britain joined a group of countries against France. Defensive measures were taken in Sussex.

In 1793, two batteries were built in Brighton. The Sussex Yeomanry was founded in 1794. Many volunteered to join this part-time cavalry to defend against Bonaparte's invasion. From 1805 to 1808, Martello towers were built along the Sussex and Kent coasts. These were defensive towers.

The Admiralty set up a visual signaling system. This allowed communication between ships, the shore, and London. Sussex had 16 signaling stations. A central fort, the Eastbourne Redoubt at Eastbourne, was built from 1804–1810. It is now home to the Royal Sussex Regiment Museum. In the 1860s, more defenses were built, including Newhaven fort.

At the start of World War I in August 1914, landowners in Sussex helped recruit volunteers. Claude Lowther, owner of Herstmonceux Castle, recruited enough men for three Southdown Battalions. They were known as Lowthers Lambs. The Royal Sussex Regiment had 23 battalions in the war. After the war, St George's Chapel in Chichester Cathedral became a memorial to the fallen soldiers. Nearly 7,000 members of the regiment died in World War I. Their names are on the chapel walls.

On the Sussex boys are stirring

In the wood-land and the Downs

We are moving in the hamlet

We are rising in the town;

For the call is King and Country

Since the foe has asked for war,

And when danger calls, or duty

We are always to the fore.

From Lowthers Lambs marching song.

When World War II began on September 3, 1939, Sussex was on the frontline. Its airfields were crucial in the Battle of Britain. Many towns were bombed. While Sussex regiments served overseas, the Home Guard defended the county. They were helped by the First Canadian Army from 1941 to early 1944.

Every part of Sussex was affected by the war. Army camps appeared everywhere. Sussex hosted many service members. These included the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division and the 30th US Division. Fighter squadrons from Belgium, France, Czech Republic, and Poland were based at Sussex airfields.

Before the D-Day landings, Sussex saw a huge build-up of military personnel and materials. Landing crafts were assembled, and Mulberry harbours were built off the coast. Five new airfields were built to support the D-Day landings. Four were near Chichester, and one near Billingshurst.

Sections of Mulberry harbor still lie broken on the seabed off Selsey Bill. They were meant for the invasion but were lost.

Industries of Sussex: From Ancient Times to Today

Sussex was an industrial county from the Stone Age. It produced flint tools early on. Later, industry moved north due to coal and steam power. The county has also been known for its agriculture.

Farming and Fishing in Sussex

Sussex remains mostly rural. Apart from the coast, it has few large towns. In 1841, over 40% of people worked in agriculture or fishing. Today, less than 2% do. The different soil types lead to varied farming.

The Weald has wet clays or dry sands. It is broken up by small fields and woods. This makes it unsuitable for intense crop farming. Mixed farming has always been common here. Field boundaries often look the same as in medieval times.

Sussex cattle are descendants of oxen. These oxen were used longer in the Weald than elsewhere in England. Agricultural writer Arthur Young said in the 18th century that Wealden cattle were "among the best of the kingdom." William Cobbett saw some of the finest cattle on the poorest farms in Ashdown Forest.

Cereal farming in the Weald has changed with grain prices. The chalk downlands were grazed by many small Southdown sheep. These sheep were suited to the poor pasture. Artificial fertilizer made cereal growing possible, but yields are still limited by soil alkalinity.

The best and most farmed soils are on the coastal plain. Here, large-scale vegetable growing is common. Glasshouse production is also along the coast, where there is more sunshine.

Fishing fleets still operate at Rye and Hastings. But the number of boats is much smaller now. Historically, fisheries were very important. They caught cod, herring, mackerel, and many other fish and shellfish. Bede wrote that St Wilfrid taught people net-fishing in 681. The Domesday Book shows extensive fisheries and 285 saltworks. Brighton fishermen's customs were recorded in 1579.

Iron Working in Sussex

In the Iron Age, wrought iron was made using a bloomery. This involved a shallow hearth dug in the ground. Clay lined it, and layers of ore and charcoal were added. A clay 'beehive' structure covered it, with holes for bellows. The material was ignited, and it took two to three days to complete. This left semi-molten lumps of iron called 'blooms'. The iron was then shaped using heat and hammering. About a dozen pre-Roman sites have been found in eastern Sussex.

The Romans used this resource fully. They improved native methods. Iron slag was used for paving Roman roads. The Roman iron industry was mainly in East Sussex. The largest sites were in the Hastings area. The Roman navy, the Classis Britannica, likely organized the industry.

Little evidence of iron production exists after the Romans left until the ninth century. Then, a basic bloomery was built at Millbrook on Ashdown Forest. Bloomery production continued until the late 15th century. A new technique from northern France allowed cast iron production. A permanent blast furnace was built. Bellows, powered by water, oxen, or horses, forced air into the furnace. This produced higher temperatures, melting the iron. The melted iron was poured into molds. This was a continuous process, usually running in winter and spring.

"Full of iron mines it is in sundry places, where for the making and fining whereof there bee furnaces on every side, and a huge deale of wood is yearely spent..."

From William Camden's description of 17th century Sussex.

Henry VIII needed cannons for his new coastal forts. Bronze cannons were very expensive. Iron cannons had been made before, but with separate barrels. In Buxted, the local vicar, Reverend William Levett, was a gun-founder. He and Ralf Hogge produced an iron muzzle-loading cannon in 1543. It was cast in one piece.

The navy complained the new guns were too heavy. But bronze was ten times more costly. So, iron guns were preferred for forts and merchant ships. An important export trade in Wealden guns grew. They were dominant until Swedish guns took over around 1620. Both men made a lot of money. Hogge built a house with a 'hog' symbol as a pun for his name.

The large supply of wood in Sussex made it good for the industry. All smelting used charcoal until the mid-18th century.

Glass Making in Sussex

The glass making industry started on the Sussex/Surrey border in the early 13th century. It thrived until the 17th century. In the 16th century, it spread to Wisborough Green, Alfold, Ewhurst, Billingshurst, and Lurgashall. Many workers were immigrants from France and Germany. The process used timber for fuel, sand, and potash.

Glass production in the English midlands started using coal. This, plus opposition to using timber in Sussex, led to the collapse of the Sussex glass industry in 1612.

Forestry and Timber in Sussex

When the Romans arrived in Sussex around AD 43, they found people smelting iron in the Andredsweald forest. Timber was used to make charcoal for smelting. Roman engineers improved roads to help produce and distribute iron more efficiently.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, written in the 9th century, described the forest covering the Sussex Weald. It said the forest was 120 miles wide and 30 miles deep (though probably closer to 90 miles wide). It was so dense that some settlements were not even recorded in the Domesday Book.

The Weald was not the only forested area. The Manhood Peninsula in western Sussex is now mostly deforested. Its name likely comes from Old English maene-wudu, meaning "men's wood" or "common wood."

Before and during Henry VIII's reign, England imported much of its naval timber. Henry wanted to source materials domestically. Sussex forests met this demand, with Sussex oak being excellent for shipbuilding. Huge amounts of wood were used for ships and charcoal. Facing dwindling wood stocks, Parliament tried to pass bills to manage them. But these bills never passed, leading to the decimation of the county's forests.

The poet Michael Drayton wrote in his early 17th-century poem Poly-Olbion about the trees complaining about the iron trade:

Jove's oak, the war-like ash, veined elm, the softer beech

Short hazel, maple plain, light asp and bending wych

Tough holly and smooth birch, must altogether burn.

What should the builder serve, the forger's turn

When under publick good, base private gain takes hold.

And we, poor woeful woods, to ruin lastly sold.

From Michael Drayton's Poly-Olbion

Despite efforts, Sussex forests continued to be used up. However, in 1760, Abraham Darby found a way to use coke instead of charcoal in blast furnaces. This moved production closer to coal mines. By then, Sussex forests were devastated, and roads ruined by transporting ore.

The High Weald still has about 35,905 hectares (139 sq mi) of woodland. This includes ancient woodland, about 7% of England's total. In the 9th century, the Sussex Weald forest was thought to be about 2,700 sq mi (700,000 ha).

Wool Industry in Sussex

In 1340-1341, Sussex had about 110,000 sheep. Edward III had his Chancellor sit on a woolsack in council. This symbolized the importance of the wool trade. In 1341, most wool production in Sussex was in the eastern part. Chichester port was extended for collecting customs on wool. Chichester was the seventh-ranked port and a wool port in the Statute of the Staple of 1353.

In the early 15th century, most wool production was within 15 miles of Lewes. In the 16th century, weavers, fullers, and dyers were found in almost every parish. Chichester was an early center for weaving cloth and spinning linen.

In 1566, an act banned the export of unfinished cloths. This led to the decline of the industry in Sussex. By the early 18th century, it had almost collapsed. Daniel Defoe noted in 1724 that Kent, Sussex, Surrey, and Hampshire were not involved in significant wool manufacturing.

Clay Working in Sussex

Much of the Mid Sussex area has clay close to the surface. This made clay a focus of industry, especially around Burgess Hill. In the early 20th century, Burgess Hill, Hassocks, and Hurstpierpoint had many kilns and clay pits.

Today, most of this industry has left. But it can still be seen in place names like "Meeds Road" and "The Kiln." Tiles and bricks from Sussex were used to build landmarks like Manchester's G-Mex. In 2007, plans were made to close the last tile works in the area. In 2015, the last tile works moved to Surrey.

Transportation in Sussex: Roads, Canals, and Railways

Roads in Sussex

After the Romans left, roads in England fell into disrepair. In Sussex, the damage was made worse by transporting materials for the iron industry. A 17th-century government report described a road between Surrey and Sussex as "very ruinous and almost impassable." In 1749, Horace Walpole complained that if you wanted good roads, "never to go into Sussex."

Roads were maintained by parishes, a system set up in 1555. This system became ineffective as traffic increased. In 1696, the first Turnpike Act was passed. It was for repairing the highway between Reigate (Surrey) and Crawley (Sussex). The act allowed for building turnpikes and collecting tolls. It also allowed borrowing money for repairs.

Other turnpike acts followed. Roads were built and maintained by local trusts and parishes. Most roads were maintained by tolls paid by passengers. Some roads were still maintained by parishes without tolls. By the mid-19th century, there were 152 Acts of Parliament for turnpikes in Sussex. A report in 1857 said there were 51 trusts covering 640 miles of road. There were 238 toll gates, about one every 2.5 miles.

The last turnpike in Sussex was built between Cripps Corner and Hawkhurst in 1841. The turnpike system, coaches, and inns declined with the rise of railways. By 1870, most turnpike trusts in Sussex closed. This put many coachmen and coachbuilders out of business. Road conditions worsened until the new county council took over maintenance in 1889.

In the early 20th century, most first-class roads had been turnpikes in 1850. During the 20th century, cars and lorries challenged the railways.

East and West Sussex have only 12 km (7.5 miles) of motorway. They also have relatively small amounts of dual carriageway. The two main east-west roads are the A27 and the A259. These roads provide major routes across Sussex. They are only dual-carriageway for part of their length. Both roads run parallel to the Sussex coast.

The main north-south road connecting the coast to the London orbital M25 is the M23/A23. According to the Highways Agency, improvements to remove traffic bottlenecks will take some time.

The first canals in Sussex were actually navigations. Their purpose was to make the lower parts of rivers usable by boats. Rivers had been neglected for centuries, making navigation difficult even for small boats.

Examples of navigations in Sussex include:

Later, true canals were built, such as:

When railways arrived, they offered an alternative to canals. Canal companies' income quickly dropped. Most canals closed by the start of World War I.

Railways in Sussex: Connecting Towns and People

In 1804, Richard Trevithick built the first steam locomotive for a railway. His seven-tonne locomotive pulled 10 tonnes of iron and 70 passengers. It traveled 9 miles at almost 5 mph.

George Stephenson built the engine Locomotion for the Stockton and Darlington railway. It opened in 1825 for passengers and goods. Locomotion pulled 36 wagons with coal, grain, and 500 passengers for 9 miles at 15 mph.

The Manchester to Liverpool railway in 1830 was the first to carry passengers and goods entirely by steam. Stephenson's Rocket was the first steam locomotive designed for fast passenger traffic.

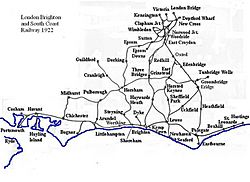

Brighton was ideal for Londoners' short holidays. In the 1830s, about 40 coaches a day traveled the London-Brighton road. The road was in poor condition. Proposals for a railway were made as early as 1806. In 1837, the London and Brighton Railway Bill was approved. It included branches to Shoreham and Newhaven. In 1838, the London and Brighton Railway Company (L&BR) said it would be a passenger-only railway.

In the 18th century, Brighton was declining. Daniel Defoe described it as 'a poor fishing town, old built'. This changed after two events:

- In 1750, Dr Richard Russell recommended Brighton for seawater cures.

- From 1783, the Prince of Wales visited Brighton regularly, making it fashionable.

These events increased visitors. In 1841, when the L&BR opened, 1,095 of Brighton's 8,137 houses were empty. But within 40 years, Brighton's population doubled.

After the Brighton line opened, branches were built to Chichester (west) and Hastings and Eastbourne (east). In 1846, the L&BR merged with other railways to form the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway(LB&SCR). The LB&SCR remained independent until the Railways Act 1921. This act merged various southern railway companies into the Southern Railway Company (SR) on January 1, 1923.

Two railway companies in Sussex were not absorbed by SR. These were Volk's Electric Railway, the world's first electric railway, opened in Brighton in 1883. The other was the West Sussex Railway, a light railway between Chichester and Selsey, opened in 1897 and closed in 1935.

SR was the smallest of four groups formed by the 1921 Act. The LB&SCR had partly electrified its network before World War I. SR decided to electrify its network using the third rail DC system.

During World War II, SR was heavily involved in transporting military traffic. It was bombed many times. After the war, SR was nationalized in 1948. It became the Southern Region of British Railways.

After John Major's victory in the 1992 General Election, the government decided to privatize the railways. Franchises were given to train operating companies (TOCs).

Currently, most rail services in Sussex are run by the Thameslink, Southern and Great Northern franchise. Govia Thameslink Railway has operated these since September 2014. This includes the Gatwick Express service between Victoria and Gatwick Airport. Southern Railway manages services to the south coast and London. Southeastern runs services between eastern Sussex and London. Thameslink runs services between Brighton and Bedford, Brighton and Cambridge, and Horsham and Peterborough.

Ports in Sussex: Gateways to the Sea

The two major ports in Sussex are at Newhaven, opened in 1579, and at Shoreham, opened in 1760. Other historical ports like Pevensey, Winchelsea, and the original medieval port of Rye are now inland.

For smaller boats, there are working harbors at Rye Harbour and Hastings. Brighton Marina, Pagham, and Chichester harbors are for leisure boats. Other old harbors like Fishbourne, Steyning, Old Shoreham, Meeching, and Bulverhythe are now filled with silt and built over.

Images for kids

-

A mid-2nd century mosaic showing Cupid riding a dolphin, discovered during the excavation of Fishbourne Roman Palace.

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |