History of Boston facts for kids

The history of Boston is a really important part of American history. In 1630, Puritan colonists from England started Boston. It quickly became a major center for politics, business, money, religion, and education in the New England area.

The American Revolution actually began in Boston. The British reacted strongly after the Boston Tea Party, and the American patriots fought back. They surrounded the British in the city. A famous battle happened at Breed's Hill in Charlestown on June 17, 1775. The colonists lost this battle, but they caused a lot of damage to the British. The Americans then won the Siege of Boston, making the British leave the city on March 17, 1776. However, the fighting and blockades hurt Boston's economy badly, and its population dropped by two-thirds in the 1770s.

Boston recovered after 1800. It became a key transportation hub for New England with its railroads. More importantly, it grew into a national center for ideas, education, and medicine. In the 1800s, Boston was a financial hub in the U.S., helping to fund railroads across the country. During the Civil War era, it was a major base for anti-slavery activities. By 1900, Irish Catholic immigrants, like the Kennedy Family, took political control of the city.

The region's industrial growth, supported by Boston's money, reached its peak around 1950. After that, many factories closed, and the city faced a decline. By the 21st century, Boston's economy had bounced back. It now focuses on education, medicine, and high technology, especially biotechnology. Many towns around Boston became places where people live and commute from.

Contents

Ancient Times in Boston

The Shawmut Peninsula was once connected to the mainland by a narrow strip of land called Boston Neck. It was surrounded by Boston Harbor and the Back Bay, which was an area where the Charles River met the sea.

Archaeological sites, like the Boylston Street Fishweir, have been found during construction in Boston. These sites show that people lived on the peninsula as far back as 7,500 years ago.

How Boston Was Founded

In 1628, the Cambridge Agreement was signed in England by the Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. This agreement made the colony self-governing, answering only to the king. John Winthrop was their leader and became the governor in the New World. He famously described the new colony as "a City upon a Hill."

Another colony, the Plymouth Colony, was founded in 1620. It later joined with the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1691.

In June 1630, the Winthrop Fleet arrived in what is now Salem. They didn't like it because there wasn't enough food. They then went to Charlestown, but it also lacked fresh water. The Puritans finally settled around a spring in what would become Boston. They bought the land from the first English settler, William Blaxton.

The 1630 settlers first called the peninsula "Trimountaine." This name came from three hills on the peninsula. Two of these hills were later leveled as the city grew. The middle one, Beacon Hill, is still a key part of Boston today. Tremont Street still uses a form of the original name.

Governor Winthrop officially founded the town of Boston on September 7, 1630. The place was named after Boston, a town in England, where many colonists came from. The name also honors Saint Botolph, who is the patron saint of travelers.

Boston's Colonial Life

Early colonists in Boston believed they had a special agreement with God. This idea, from Winthrop's "City upon a Hill" speech, shaped everything in Boston. It led colonists to create laws about morality, marriage, church attendance, and education. They also punished those they considered sinners.

Some of America's first schools and colleges were founded here. The Boston Latin School (1635) and Harvard College (1636) were started soon after Boston was settled by Europeans.

Colonial Boston's town officials were chosen every year. These roles included selectman, fence viewer, and hayward.

Boston's Puritans were very strict about religious ideas. They exiled or punished people who disagreed with them. For example, Anne Hutchinson was banished for her religious views. Obadiah Holmes, a Baptist minister, was whipped in public in 1651 because of his religion. Mary Dyer was hanged on Boston Common in 1660 for being a Quaker.

The Boston Post Road connected Boston to New York and other major settlements. This important road helped people and goods travel.

From 1686 to 1689, Massachusetts and nearby colonies were united under the Dominion of New England. It was led by Sir Edmund Andros, who was appointed by King James II. Andros was unpopular, especially because he supported the Church of England in a Puritan city. On April 18, 1689, he was overthrown in a short revolt. The Dominion was not restarted.

Big Problems in the 1700s

Boston faced several serious smallpox outbreaks from 1636 to 1698. The worst one was in 1721–22, killing 844 people. Out of 10,500 residents, 5,889 caught the disease. People tried to stop smallpox by isolating the sick. For the first time in America, inoculation was tried. This process gave people a mild form of the disease to make them immune. It was very controversial because it could be dangerous. Zabdiel Boylston and Cotton Mather introduced it.

In 1755, Boston experienced the biggest earthquake ever to hit the Northeastern United States. It was called the Cape Ann earthquake. It caused some damage to buildings but no deaths.

The first "Great Fire" of Boston destroyed 349 buildings on March 20, 1760. The Boston Fire Department fought many significant fires like this one.

Boston and the American Revolution (1765–1775)

Boston was very active in protesting the Stamp Act of 1765. Its merchants avoided paying customs duties, which angered British officials. Governor Francis Bernard (1760–69) wanted to stop the growing opposition in town meetings. Historians say his letters to London exaggerated the situation, making British officials think troops were needed.

In October 1768, four thousand British Army troops arrived in Boston. This huge show of force only made tensions worse.

By the late 1760s, Americans focused on their rights as Englishmen. They especially believed in "No Taxation without Representation," an idea promoted by John Rowe, James Otis, and Samuel Adams. Boston played a main role in starting both the American Revolution and the American Revolutionary War.

The Boston Massacre happened on March 5, 1770. British soldiers fired into unarmed protesters outside the British custom house, killing five civilians. This greatly increased tensions. Parliament still insisted on its right to tax Americans and put a small tax on tea. Americans in the 13 colonies stopped merchants from selling the tea. But a shipment arrived in Boston Harbor.

On December 16, 1773, 30–60 local Sons of Liberty, dressed as Native Americans, dumped 342 chests of tea into the harbor. This event is known as the Boston Tea Party. The British government reacted with harsh laws, closing the Port of Boston and taking away Massachusetts's self-government. The other colonies supported Massachusetts, forming the First Continental Congress. They also started arming and training militia groups.

The British sent more troops to Boston, and General Thomas Gage became governor. When Gage found out the Patriots had a shadow government in Concord, he sent troops to break it up. Paul Revere, William Dawes, and Dr. Samuel Prescott made their famous midnight rides to warn the Minutemen in nearby towns. This led to the Battle of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, the first battle of the American Revolution.

Militia units from all over New England came to defend Boston. Congress sent General George Washington to take command. The British were trapped in the city. They won the Battle of Bunker Hill but suffered very heavy losses. Washington brought in cannons, forcing the British out. The patriots took full control of Boston. The American victory on March 17, 1776, is celebrated as Evacuation Day. Boston still celebrates its revolutionary past with sites along the Freedom Trail.

Boston in the 1800s

Boston changed a lot from 1780 to 1800. It went from a small, struggling town to a busy seaport and a diverse center. It became one of the world's richest trading ports, exporting goods like rum, fish, and tobacco. The American Revolution and the British blockade had caused many people to leave the city. But the population grew from 10,000 in 1780 to nearly 25,000 by 1800. Slavery was ended in Massachusetts in 1783, giving Black people more freedom to move around.

Boston was part of the "triangular trade" in New England. It received sugar from the Caribbean and turned it into rum and molasses. Later, candy making also became important. Companies like Necco and Schrafft's had facilities in Boston. The Boston Fruit Company, which later became Chiquita Brands International, started importing tropical fruit in 1885.

Boston was a town until it became a city in 1822. The second mayor, Josiah Quincy III, improved roads and sewers. He also organized the city's dock area around the new Faneuil Hall Marketplace, known as Quincy Market. By the mid-1800s, Boston was a major manufacturing center, known for clothing, leather goods, and machinery. Manufacturing soon became more important than international trade.

A network of small rivers and canals, like the Middlesex Canal, helped transport goods. By the 1850s, an even bigger network of railroads helped industry and trade. For example, in 1851, Jordan Marsh, a Department store, opened in downtown Boston.

Several turnpikes (toll roads) were built to help transportation, especially for bringing cattle and sheep to markets. The Worcester Turnpike (now Massachusetts Route 9) was built in 1810.

The Boston Brahmins

Boston's "Brahmin elite" developed a special set of values by the 1840s. They were wealthy, educated, and dignified. The ideal Brahmin was expected to support the arts, give to charities, and be a community leader. They warned against greed and emphasized personal responsibility. This system was supported by strong family ties. Young men went to the same schools and colleges and even had their own way of speaking. Most Brahmins belonged to the Unitarian or Episcopal churches.

A famous poem about Boston says: "And here's to good old Boston / The land of the bean and the cod / Where Lowells talk only to Cabots / and Cabots talk only to God." This shows how wealthy colonial families like the Lowells and Cabots ruled the city. But in the 1840s, many new immigrants arrived from Europe, including large numbers of Irish and Italians. This made Boston's population much more Roman Catholic.

Fighting Slavery

In 1831, William Lloyd Garrison started The Liberator, an abolitionist newspaper in Boston. It called for "immediate and complete emancipation of all slaves" in the United States. This made Boston the center of the abolitionist movement. After the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, Boston became a stronghold of anti-slavery ideas. Attempts by slave-catchers to arrest runaway slaves often failed.

Irish Immigrants Arrive

The first Irish settlers came in the early 1700s. Many were indentured servants who worked for five to seven years before becoming free. They had to hide their Catholic faith because it was banned. Later, in 1718, Presbyterian groups from Ulster in Ireland began arriving. They were called Ulster Irish, or later, Scots-Irish. The Puritan leaders first sent them to the edges of the colony, but by 1729, they could set up a church in downtown Boston.

Throughout the 1800s, Boston became a home for Irish Catholic immigrants, especially after the potato famine of 1845–49. Their arrival changed Boston from a mostly Anglo-Saxon Protestant city to a more diverse one. Yankees hired the Irish as workers and servants, but there was little social mixing. In the 1850s, an anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant movement called the Know Nothing Party rose up against the Irish. But in the 1860s, many Irish immigrants joined the Union army in the American Civil War. Their bravery helped soften the Yankees' harsh feelings about the Irish.

Even today, Boston has the largest percentage of Irish-descended people of any U.S. city. With their growing population and strong community organization, the Irish took political control of the city. The Yankees remained in charge of finance, business, and higher education. The Irish left their mark in many ways: in neighborhoods like Charlestown and South Boston; in the name of the basketball team, the Boston Celtics; in the powerful Irish-American political family, the Kennedys; and in the founding of Catholic Boston College as a rival to Harvard.

The Great Fire of 1872

The Great Boston Fire of 1872 began on November 9. In two days, the huge fire destroyed about 65 acres (260,000 m²) of the city. This included 776 buildings in the financial district, causing $60 million in damage.

Boston's High Culture

From the mid-to-late 1800s, the Boston Brahmins were very active in culture. They were known for their refined literature and generous support of the arts. Many famous writers lived in Boston, including Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.. Historians like Francis Parkman also lived there. Boston had many great publishers and magazines, such as The Atlantic Monthly.

Higher education became more important, especially at Harvard (in Cambridge) and other schools. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) opened in Boston in 1865. The first medical school for women, The Boston Female Medical School, opened in 1848. The Jesuits opened Boston College in 1863.

The Brahmins were the main writers and audience for high culture. New Irish, Jewish, and Italian cultures had little impact on this elite group.

To entertain a different audience, the first vaudeville theater opened in Boston on February 28, 1883.

The public Boston Museum of Natural History (now the Boston Museum of Science) was founded in 1830. It taught the public and professionals about natural history, including ocean life and geology.

Getting Around Boston

As the population grew quickly, Boston-area streetcar lines helped create many "streetcar suburbs." Middle-class people lived in these suburbs and rode the subway into the city for work. Downtown traffic got worse, leading to the opening of North America's first subway on September 1, 1897. This was the Tremont Street Subway.

Between 1897 and 1912, underground rail lines were built to Cambridge and East Boston. Elevated and underground lines also expanded into other neighborhoods. Today, the regional train and bus network is managed by the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. Two main train stations, North Station and South Station, were built to combine downtown railroad terminals.

Boston in the 1900s

Early 1900s

In 1900, Julia Harrington Duff became the first Irish Catholic woman elected to the Boston School Committee. She worked to update textbooks and protect job opportunities for local Boston women in the school system.

On January 15, 1919, the Boston Molasses Disaster happened in the North End. Twenty-one people died and 150 were hurt when a huge wave of molasses rushed through the streets at about 35 mph. It took over six months to clean up the molasses from streets, buildings, and homes. Boston Harbor stayed brown until summer.

In the summer of 1919, over 1,100 members of the Boston Police Department went on strike. Boston saw riots because there were very few police officers. Calvin Coolidge, then governor of Massachusetts, became famous for ending the violence by replacing almost the entire police force. The 1919 Boston Police Strike set a precedent for police unions across the country.

Mid-Century Changes

In 1934, the Sumner Tunnel created the first direct road connection under Boston Harbor, linking the North End and East Boston.

In May 1938, the first public housing project, Old Harbor Village, opened in South Boston.

By 1950, Boston was struggling. Factories were closing and moving south where labor was cheaper. Boston's strengths, like its banks, hospitals, and universities, were not enough to stop the decline. To fix this, Boston's leaders started "urban renewal" plans. These plans tore down several neighborhoods, including the New York Streets district in the South End, the old West End, and Scollay Square.

New buildings and projects replaced these areas. These projects forced thousands of people to move and closed hundreds of businesses. This caused a lot of anger, which in turn helped save many other historic neighborhoods.

In 1948, William F. Callahan published the Master Highway Plan for Metropolitan Boston. Parts of the financial district, Chinatown, and the North End were torn down for construction. By 1956, the northern part of the Central Artery was built. However, strong local opposition led to the southern downtown part being built underground. The Dewey Square Tunnel connected downtown to the Southeast Expressway. In 1961, the Callahan Tunnel opened, running next to the older Sumner Tunnel.

By 1965, the first Massachusetts Turnpike Extension was finished. Proposed highways like the Inner Belt in Boston and nearby towns were canceled due to public outcry. In 1971, public protests also stopped I-95 from going into downtown Boston. Demolition had already started along the Southwest Corridor. This area was instead used to reroute the Orange Line and Amtrak's Northeast Corridor.

World War II and Beyond

On November 28, 1942, Boston's Cocoanut Grove nightclub had the Cocoanut Grove fire. It was the deadliest nightclub fire in U.S. history, killing 492 people.

In 1953, the Columbia Point public housing projects were finished in Dorchester. In 1966, the Columbia Point Health Center opened. It was the first community health center in the country.

In the 1970s, after years of economic trouble, Boston boomed again. Financial companies grew, and Boston became a leader in the mutual fund industry. Health care expanded, and hospitals like Massachusetts General Hospital became leaders in medical innovation. Higher education also grew, with universities like Harvard, MIT, Boston College, and BU attracting many students. Many stayed and became residents. MIT graduates, in particular, started many successful high-tech companies. This made Boston second only to Silicon Valley as a high-tech center.

In 1974, Boston faced a crisis. A federal judge ordered desegregation busing to integrate the city's public schools. This caused racial violence in several neighborhoods, as many white parents resisted the plan. Public schools became places of unrest. Tensions continued through the mid-1970s.

The Columbia Point housing complex got worse until only 350 families lived there in 1988. In 1984, the city gave control of the complex to a private developer. They redeveloped it into a mixed-income community called Harbor Point Apartments. This was a very important example of revitalization and was the first federal housing project to be converted to private, mixed-income housing in the USA.

On March 18, 1990, the largest art theft in modern history happened in Boston. Twelve paintings, worth over $100 million, were stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. The paintings have not been found.

The Big Dig and Transit in the 2000s

In 2007, the Central Artery/Tunnel project was finished. Nicknamed the Big Dig, it was planned in the 1980s. Construction began in 1991. The Big Dig moved the rest of the Central Artery underground, made the north-south highway wider, and created local bypasses. The Ted Williams Tunnel became the third highway tunnel to East Boston and Logan International Airport. The Big Dig also created the famous Zakim Bunker Hill Bridge and over 70 acres (280,000 m²) of public parks. The project has helped ease Boston's traffic, but it was the most expensive construction project in U.S. history.

The city also saw other transportation projects. These included improvements to its public transit system, especially the commuter rail and the "Silver Line" bus system. The Port of Boston and Logan International Airport were also developed.

Boston in the 21st Century

Recently, Boston has seen some of its local institutions and traditions change. For example, Boston Globe was bought by The New York Times. The Jordan Marsh department store was acquired by Macy's. Many prominent financial institutions were lost to mergers or failures. In 2004, Bank of America acquired FleetBoston Financial, and P&G announced plans to acquire Gillette.

Despite these changes, Boston still feels unique among world cities. In many ways, it has improved. Racial tensions have eased, and city streets are lively. Boston has once again become a center for new ideas in technology and politics. However, the city has had to deal with gentrification and rising living costs. According to Money Magazine, Boston is one of the world's most expensive cities.

Boston hosted the 2004 Democratic National Convention. The city was also in the national spotlight in early 2004 during the debate over same-sex marriage. After the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled that such marriages could not be banned, supporters and opponents gathered at the Massachusetts State House.

Also in 2004, the Boston Red Sox won their first World Series in 86 years. They won again three years later in 2007.

On April 15, 2013, two bombs exploded during the Boston Marathon. Three people were killed and hundreds were injured.

On October 30, 2013, the Boston Red Sox won their eighth World Series title.

How Boston Grew

The City of Boston grew in two main ways: by filling in land and by adding nearby towns.

Between 1630 and 1890, the city tripled its physical size by land reclamation. This meant filling in marshes, mud flats, and gaps between docks along the waterfront. This process was called "cutting down the hills to fill the coves." The most intense filling happened in the 1800s. Starting in 1807, the top of Beacon Hill was used to fill a 50-acre mill pond. This area later became the Bulfinch Triangle Historic District. The current State House sits on this shortened Beacon Hill.

Landfill projects in the mid-1800s created large parts of what are now the South End, West End, Financial District, and Chinatown. After The Great Boston Fire of 1872, building rubble was used as landfill along the downtown waterfront.

The biggest land reclamation project was filling in the Back Bay in the mid-to-late 1800s. Almost 600 acres (240 hectares) of marshlands west of the Boston Common were filled with gravel brought by train from Needham Heights. Boston also grew by adding nearby communities like East Boston, Roxbury, Dorchester, West Roxbury, South Boston, Brighton, Allston, Hyde Park, and Charlestown. Some of these areas also grew with landfill.

Several ideas to combine local governments failed. People worried about losing local control, corruption, and Irish immigration.

The state government has combined some functions in Eastern Massachusetts. These include the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (public transit), the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (water and sewer), and the Metropolitan District Commission (parks).

Timeline of annexations and related developments:

- 1705 – Hamlet of Muddy River became Brookline.

- 1804 – First part of Dorchester was added.

- 1851 – West Roxbury (including Jamaica Plain and Roslindale) separated from Roxbury.

- 1855 – Washington Village, part of South Boston, was added.

- 1868 – Roxbury was added.

- 1870 – The last part of Dorchester was added.

- 1873 – Brookline–Boston annexation debate of 1873 (Brookline was not added).

- 1874 – West Roxbury (including Jamaica Plain and Roslindale) was added.

- 1874 – Town of Brighton (including Allston) was added.

- 1874 – Charlestown was added.

- 1912 – Hyde Park was added.

- 1986 – A vote to create Mandela from parts of Roxbury, Dorchester, and the South End passed locally but failed city-wide.

Timeline of land reclamation:

- 1857 – Filling of the Back Bay began.

- 1882 – Present-day Back Bay fill was completed.

- 1890 – Charles River landfill reached Kenmore Square.

- 1900 – Back Bay Fens fill was completed.

Images for kids

-

Copp's Hill Burying Ground, founded 1659

-

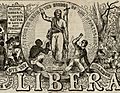

An artist's depiction of the 1689 Boston revolt

-

Idealized illustration of Copley Square from an 1890s clothing catalog, prominently featuring H. H. Richardson's Trinity Church

-

Boston's Tremont Street Subway is the oldest subway tunnel in North America

-

The Old John Hancock Tower and Boston skyline, as it appeared in 1956

-

Local universities like MIT were important to the emergence of Boston's tech industry

-

Boston's Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway is a result of the Big Dig.

-

The Boston skyline from Chelsea, Massachusetts

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |