Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve |

|

|---|---|

|

IUCN Category V (Protected Landscape/Seascape)

|

|

Mount St. Elias, the second highest point in both the United States and Canada

|

|

The location of Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve within Alaska

|

|

| Location | Chugach Census Area, Copper River Census Area, Southeast Fairbanks Census Area and Yakutat City and Borough, Alaska, United States |

| Nearest city | Copper Center, Alaska |

| Area | 13,175,799 acres (53,320.57 km2) 8,323,147.59 acres (3,368,258.33 ha) (Park only) 4,852,652.14 acres (1,963,798.65 ha) (preserve only) |

| Established | December 2, 1980 (park & preserve) December 1, 1978 (national monument) |

| Visitors | 79,450 (in 2018) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Part of | Kluane / Wrangell-St. Elias / Glacier Bay / Tatshenshini-Alsek |

| Criteria | Natural: (vii), (viii), (ix), (x) |

| Inscription | 1979 (3rd Session) |

| Extensions | 1992, 1994 |

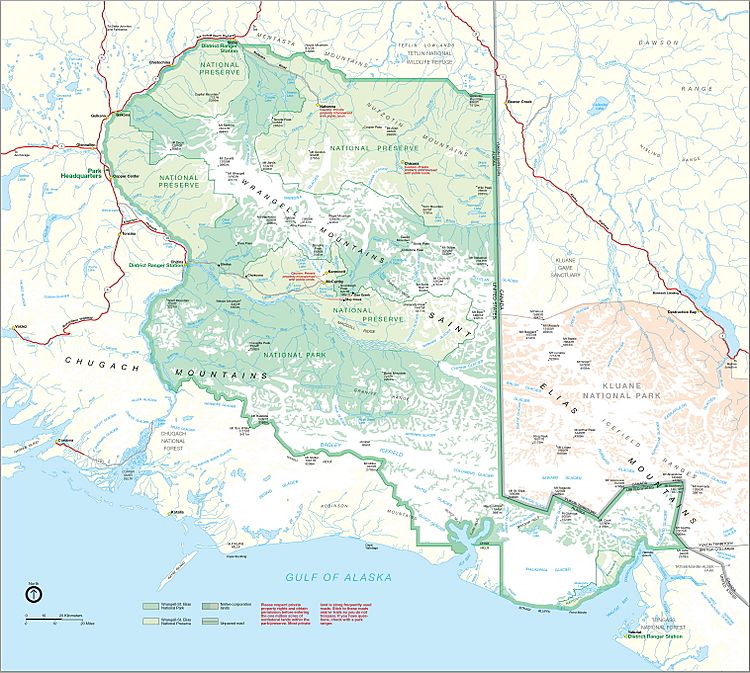

Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve is a huge and amazing place in south-central Alaska. It's managed by the National Park Service. This special area became a national park and preserve in 1980. It's so important that it's also part of an International Biosphere Reserve and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

This park and preserve is the largest area the National Park Service looks after. It covers over 13 million acres, which is like fitting six Yellowstone National Parks inside! The park has a big part of the Saint Elias Mountains, home to some of the tallest peaks in the United States and Canada. These mountains are very close to the ocean, making them incredibly dramatic. Wrangell–St. Elias is next to Canada's Kluane National Park and Reserve and close to Glacier Bay in the U.S. A key difference between the park and preserve areas is that you can hunt for sport in the preserve, but not in the park. Also, a huge part of the park and preserve is a special "wilderness" area, the largest in the United States.

Wrangell–St. Elias was first made a national monument in 1978 by President Jimmy Carter. This happened to protect the land until a final law was passed. The park has very long, cold winters and short summers. Its towering mountains were formed by plate tectonics. Mount Saint Elias, at over 18,000 feet, is the second-tallest mountain in both the U.S. and Canada. The park's landscape has been shaped by both volcanoes and glaciers. Mount Wrangell is an active volcano, and there are others in the area. The park also has huge glaciers like Malaspina Glacier, Hubbard Glacier, and Nabesna Glacier. The Bagley Icefield covers much of the park's middle section, holding 60% of Alaska's permanent ice. In the past, the town of Kennecott was a busy copper mining town from 1903 to 1938. Today, its old mine buildings are a National Historic Landmark.

Contents

Exploring the Park's Geography

Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve includes the entire Wrangell mountain range. It also covers the western part of the Saint Elias Mountains and the eastern part of the Chugach Mountains. Smaller mountain ranges like the Nutzotin Mountains and Granite Range are also found here. Wide rivers flow through glacial valleys between these mountains. These include the Chitina River, Chisana River, and Nabesna River. Most of these rivers flow into the Copper River, which runs along the park's western edge.

The park is home to many glaciers and huge icefields. The Bagley Icefield covers parts of the St. Elias and Chugach ranges. The Malaspina Glacier covers most of the park's southeastern area. The Hubbard Glacier is at the park's far eastern border and is the largest tidewater glacier in North America. The park's eastern boundary is Alaska's border with Canada. Here, it connects with Kluane National Park and Reserve.

To the southeast, the park is bordered by Yakutat Bay and the Gulf of Alaska. The southern border follows the top of the Chugach Mountains, next to Chugach National Forest. The Copper River forms the western boundary. The northern boundary follows the Mentasta Mountains and touches Tetlin National Wildlife Refuge.

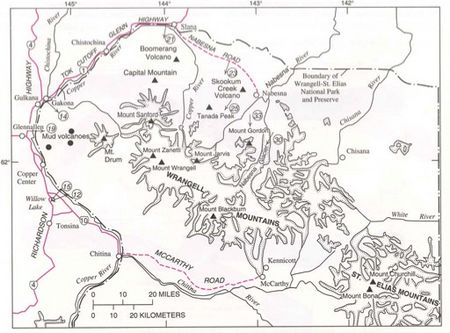

Mount St. Elias is the second-tallest mountain in both Canada and the United States. Nine of the 16 tallest peaks in the U.S. are in this park. The park also has North America's largest subpolar icefield, many glaciers, rivers, an active volcano, and the historic Kennecott copper mines. Both the St. Elias and Wrangell mountain ranges have had volcanic activity. The St. Elias volcanoes are thought to be no longer active. However, some volcanoes in the Wrangell Range have been active more recently. Mount Blackburn is the tallest of the ten volcanoes found in the western Wrangell Range. Mount Wrangell is the most recently active.

About 66% of the park and preserve land is a special "wilderness" area. This means it's kept as natural as possible. The Wrangell–Saint Elias Wilderness is the largest wilderness area in the United States.

The park is divided into national park lands and preserve lands. In park lands, only local rural residents can hunt for food. In preserve lands, anyone can hunt for sport. Preserve lands include areas like the Chitina valley and parts of the Copper River valley.

You can reach the park by highway from Anchorage. Two rough gravel roads, the McCarthy Road and the Nabesna Road, go through the park. These roads let you reach parts of the park's interior for camping and hiking. You can also fly into the park using chartered airplanes. In 2018, about 79,450 people visited Wrangell–St. Elias. The park area has a few small towns. Nabesna and Chisana are in the north. Kennicott and McCarthy are close together in the center. Chitina is a gateway town where the McCarthy Road meets the Edgerton Highway.

Fun Activities in the Park

The park is open all year. Most of its facilities are open from May to September. Some places open later in May and close in mid-August. The main visitor center stays open on weekdays during winter.

The Edgerton Highway runs along the Copper River on the park's western side. The park's main office and visitor center are near Copper Center. To get into the park's middle, you can use the Nabesna Road and the McCarthy Road. You can walk to the old mining town of Kennecott from the end of the McCarthy Road. You can also get to remote areas by using air taxi services.

The Kendesnii campground on the Nabesna Road is the only campground managed by the Park Service. There are other private campgrounds and places to stay along the McCarthy and Nabesna roads. The park also has fourteen public-use cabins. Most of these cabins can only be reached by air. A few are near the Slana Ranger Station and can be reached by road. You can camp anywhere in the backcountry without a permit. There are not many marked trails in the park.

Mountain biking is mostly limited to roads because the ground can be very wet in summer. Floating down the rivers is a popular way to see the park. You can float on the Copper, Nizina, Kennicott, and Chitina rivers. Since the park has some of North America's tallest peaks, it's a popular spot for mountain climbing. Of Alaska's 70 tallest mountains, 35 are in the park. Climbing these peaks is very challenging and requires special trips to remote and dangerous areas.

Besides the Copper Center visitor center, the park has a visitor center at Kennecott. There's also an information station on the McCarthy Road. Ranger stations are located in Slana, Chitina, and Yakutat. The Yakutat ranger station is shared with Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. The park has three improved airstrips at McCarthy, May Creek, and Chisana. Many smaller, unimproved airstrips are scattered around the park. Air taxis offer sightseeing tours and transport visitors within the park. They are based in Glennallen, Chitina, Nabesna, and McCarthy. Air taxis can also take you to sea kayak tours near Icy Bay. Farther east along the park's coast, cruise ships often visit Hubbard Glacier in Yakutat Bay.

Hunting and trapping for sport are only allowed in the preserve lands. Local residents can hunt for food in both the park and preserve. Hunting is managed by the National Park Service and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Using off-road vehicles (ORVs) is limited to specific routes, and you need a permit to use them in the preserve.

Understanding the Park's Geology

The southern part of Alaska is made up of different land pieces called terranes. These pieces have been pushed against the North American landmass by plate tectonics. The Pacific Plate moves northwest, sliding under Alaska. This movement squeezes the land, creating mountain ranges. Pieces of land carried on the Pacific Plate also get pushed against Alaska. They get folded and squeezed but don't fully go into the Earth. This is why many terranes, like the Wrangellia composite terrane, have been added to Alaska's southern coast.

This process also creates volcanoes further inland from where the plates meet. Today, the Yakutat Terrane is being pushed under land of similar density. This causes the land to rise and leads to a mix of land being added and land sliding under. Almost all of Alaska is made of these terranes pushed against North America. The coastal area has many large earthquakes. Big quakes happened in 1899, 1958, and the huge 1964 Alaska earthquake (magnitude 9.2). The 1979 St. Elias earthquake was also very strong.

Six terranes and one sedimentary belt have been found in Wrangell–St. Elias. They include the Windy or Yukon-Tanana (180 million years ago), Gravina-Nutzotin Belt (120 MYa), Wrangellia, Alexander, Chugach (110-67 MYa), Prince William (50MYa), and Yakutat terranes (starting 26 MYa). The Wrangellian rocks have fossils and volcanic rocks mixed together.

Alaska's coast looked much like it does today about 50 million years ago. This was after the Kula Plate completely slid under North America. The Pacific Plate has been sliding under southern Alaska for about 26 million years. The oldest volcanoes in Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve are about 26 million years old. They are near the Alaska-Yukon border in the St. Elias Range. Volcanic activity has moved north and west from that area since then.

Volcanic Activity in the Park

Most of the volcanoes in the Wrangell area are at the western end of the Wrangell Mountains. These volcanoes are unusual because they don't usually erupt explosively. Most are very large shield volcanoes. They grew quickly from huge flows of lava that came from many spots. Their growth is linked to the arrival of the Yakutat terrane. There was a lot of activity until about 200,000 years ago. Now, very large lava flows are not expected. Most of the Wrangell volcanoes are shield volcanoes with big collapsed areas called calderas at their tops. All but Mount Wrangell have been changed by glaciers, making them sharper and steeper. Smaller cinder cones formed around the shield volcanoes after the main volcano.

The ten tallest peaks in the Wrangell Mountains are all volcanoes. Several are among the largest volcanoes in the world. Mount Wrangell is the only Wrangell volcano still considered active. It is 14,163 feet tall. It was built by many large lava flows from 600,000 to 200,000 years ago. Smaller eruptions were reported in 1784, 1884–85, and 1900. The gently sloping top has an ice-filled caldera that is about 3.6 miles by 2.5 miles. Three craters with steam vents create a steam plume that can be seen on clear days. The top sometimes has small steam explosions that can cover the ice with ash. In the 1980s, the heat from the summit melted a lot of ice, forming a small lake. This activity has stopped since 1986, and ice has built up again. The last large lava eruption from Wrangell was about 50,000 to 100,000 years ago. The summit caldera is thought to have collapsed between 200,000 and 50,000 years ago. Mount Zanetti is a large cinder cone on Wrangell's side, thought to be less than 25,000 years old.

Mount Drum is the westernmost Wrangell volcano. It is 12,010 feet high and stands out more than much taller mountains nearby. Mount Drum is either a shield volcano or a stratovolcano. It has been greatly worn down by glaciers. Explosive activity about 250,000–150,000 years ago destroyed its original summit. These eruptions caused large mudflows, which were the last activity at Mount Drum. Mount Drum has at least eleven glaciers flowing from its icy top.

Mount Sanford is the tallest of the western Wrangell volcanoes at 16,237 feet. It is the 13th tallest peak in North America. It is a complex shield volcano that first formed about 900,000 years ago. Its last eruption was likely between 320,000 and 100,000 years ago. Like Mount Drum, Mount Sanford has a large icefield that feeds many glaciers. Capital Mountain is a smaller shield volcano near Mount Sanford, about 10 miles wide. Its top has collapsed into a caldera about 2.5 miles wide. Its last activity was about a million years ago, and glaciers have greatly eroded it. Tanada Peak is an older and larger neighbor of Capital Mountain, 9,358 feet tall. It has a summit caldera about 4 by 5 miles. This shield volcano last erupted 900,000 years ago and has been cut by glaciers. The Skookum Creek Volcano is a heavily eroded volcanic center. It was active between 3.2 million and 2 million years ago. Its caldera is surrounded by domes of dacite and rhyolite. Mount Jarvis is a shield volcano, 13,421 feet high, with unclear summit calderas. It is covered with ice and erupted between 1.7 million and 1 million years ago. Mount Blackburn is the highest point in the Wrangells at 16,390 feet. It is the 12th tallest peak in North America and the oldest volcano in the range. It is a shield volcano with a filled caldera that was active between 4.2 million and 3.4 million years ago. Mount Blackburn is covered in ice and is the source of Kennicott Glacier and Nabesna Glacier. The Boomerang volcano is a very small shield volcano, only rising 3,949 feet. It is at least one million years old. Mount Gordon is a cinder cone, one of the largest in the Wrangells at 9,040 feet.

Several hot springs or mud volcanoes near Mount Drum release warm, salty water with carbon dioxide. The largest are called Shrub, Upper Klawasi, and Lower Klawasi. Their deposits of mud have built cones 150 to 300 feet high and 8,000 feet wide.

The main volcanoes in the St. Elias Range are Mount Bona and Mount Churchill. At 16,421 feet and 15,638 feet, they are among the tallest volcanoes in the United States and North America. Churchill is often seen as a smaller peak of Bona. Both are ice-covered stratovolcanoes. Churchill is the source of the White River Ash. It erupted around 100 AD and 700 AD, spreading ash across much of Alaska and northwestern Canada.

Glaciers and Icefields in the Park

The mountains in Wrangell–St. Elias hold 60% of Alaska's glacial ice. This covers more than 1,700 square miles. The glaciers have moved forward and backward many times, reaching the sea and filling the Copper River valley. A glacial dam in the valley held back a large lake called Lake Atna during the Ice Age. When the lake drained, it carved out the riverbed. Several glaciers here are very famous. The Malaspina Glacier is the largest piedmont glacier in North America. The Hubbard Glacier is 75 miles long and is the longest tidewater glacier in Alaska. The Nabesna Glacier is the world's longest valley glacier, stretching over 53 miles.

Most glaciers in Wrangell–St. Elias are shrinking. The Bagley Icefield has become thinner, and its glaciers have retreated. This includes parts that feed the Malaspina Glacier, which is also shrinking or not moving. About 1,000 years ago, Malaspina's western and eastern parts filled Icy Bay and Yakutat Bay. However, the Hubbard Glacier has been growing since 1894, closing off Russell Fjord.

Minerals and Mining History

Five main mining areas were developed in Wrangell–St. Elias between the 1890s and 1960s. Gold was found in the Bremner area in 1901 and near Kennecott in the Nizina area. Most of this was placer gold, found in riverbeds and obtained by hydraulic mining. Copper nuggets were also found with the gold. They were usually thrown away because it was too expensive to ship them. Other gold discoveries were made in the Chisana area. During the 1930s, hard rock ore was mined in the Nabesna area.

The main source of copper was the Kennecott mine, next to the Kennicott Glacier. The copper ore found there was incredibly rich, with 70% copper when first discovered. It was one of the richest copper finds ever. Over 536,000 metric tons of copper and about 100 metric tons of silver were produced in total. After the richest ore was gone, the mines worked on other copper deposits. The copper is believed to have dissolved in hot water moving through copper-rich rock. Then it was redeposited in a concentrated form in limestone. Many other sites on the south side of the Wrangells were explored. Some even produced small amounts of ore, but none were mined for profit. Large, but low-grade, deposits of nickel and molybdenum were looked into as late as the 1970s.

Park History and Development

Early Exploration and People

Archaeological findings show that people first came to the Wrangell Mountains around 1000 AD. The Ahtna people settled in small groups along the Copper River. Some Upper Tanana speakers settled along the Nabesna and Chisana Rivers. The Eyak people lived near the mouth of the Copper River on the Gulf of Alaska. Along the coast, the Tlingit people spread out, with some settling at Yakutat Bay.

The first Europeans in the area were Russian explorers and traders. Vitus Bering landed here in 1741, and fur traders followed. A Russian trading post was set up in 1793. Another company set up a competing post in 1796. The Shelikov Company sent Dmitri Tarkhanov to explore the lower Copper River. He was looking for copper deposits because native peoples used tools made of pure copper. Another exploration group was killed by natives in 1797. Semyen Potochkin had more success in 1798. He reached the mouth of the Chitina River and spent the winter with the Ahtna. In 1799, Konstantin Galaktionov reached the Tazlina River but was hurt in an attack. He was killed on a return trip in 1803. The Tlingit and Eyak people attacked and destroyed the Russian post at Yakutat in 1805. It wasn't until 1819 that another group explored the Copper River again. They reached the upper part of the river and set up the Copper Fort trading post. In 1848, a group trying to reach the Yukon River was killed by the Ahtna, ending Russian exploration.

After the United States bought Alaska in 1867, there wasn't much American interest in the area. This changed when gold was found in the Yukon Territory in the 1880s. George Holt was the first American known to explore the lower Copper River in 1882. In 1884, John Bremner looked for gold there. That same year, a U.S. Army group tried to explore the lower river. They found a way to the interior over a glacier. In 1885, Lieutenant Henry Tureman Allen fully explored the Copper and Chitina rivers. He then crossed the Alaska Range and reached the Yukon River system. The Allen expedition also noticed that native peoples along the Copper River used copper. Other expeditions explored the coastal regions in the late 1880s. An 1891 expedition traveled down the Nizina, Chitina, and Copper Rivers from the north.

The Kennecott Copper Mines

When gold was discovered in the Canadian Klondike, prospectors came to the Copper River area and found some gold. Explorers' reports of copper tools and nuggets led the U.S. Geological Survey to send a geologist, Oscar Rohn, to find the source. Rohn reported finding copper ore in Kennicott Glacier but didn't find the main source. Soon after, prospectors Jack Smith and Clarence Warner supposedly saw a green spot on a hillside. This turned out to be a very rich copper deposit. Engineer Stephen Birch bought the rights to this deposit. He started the Alaska Copper and Coal Company in 1903 to mine it. Birch got money from investors like J. P. Morgan and the Guggenheim family. They became known as the "Alaska Syndicate." His company became Kennecott Mines in 1906, and later the Kennecott Copper Corporation. The town was named after the glacier, but the spelling was changed from "Kennicott" to "Kennecott." Other copper deposits were found south of the Wrangells at Bremner and Nizina. Smaller gold and copper deposits were found in the Nabesna area.

Developing this remote site needed a railway 195 miles long. It cost $23.5 million to build at the time. The Copper River and Northwestern Railway (CR&NW) took five years to build. It went to Cordova on the coast. The towns of Chitina and McCarthy grew up along the railway line. The Kennecott mine used surface mining, underground tunnels, and even mined ore from glacial ice.

By the 1920s, the highest-quality ore was used up. The mine's activity slowed down into the 1930s. The Kennecott operation finally closed in 1938. It had extracted over 4.5 million tons of ore, which produced 600,000 tons of copper and 562,500 pounds of silver. This made a profit of $100 million for the investors.

Reports of oil and gas near Cape Yakutaga and Controller Bay led to oil exploration along the southern coast. A small oilfield at Katalla produced oil from 1903 to 1933. It closed when its refinery was destroyed by fire. These oil deposits were why the coast from Icy Bay to the Copper River delta was not included in the future park. Coal was also found near Kushtaka Lake. A boom happened from 1974 to 1977 when the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System was built near the park's western edge. This boom was short-lived. Local residents went back to trapping, fishing, and guiding hunters for their living. Thirteen test wells were drilled offshore in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Becoming a National Park

The first ideas for protecting lands in this region came from the U.S. Forest Service in 1908. Early studies of possible new park areas in Alaska happened in the 1930s and 1940s. In 1939, Ernest Gruening, who later became governor of Alaska, suggested creating a park in the Chitina Valley. He also proposed a national monument for the Kennecott mine site. President Franklin D. Roosevelt didn't act on this, saying there was no rush and that all non-defense matters should wait for World War II.

Canada proposed an international park for the St. Elias Mountains in 1942. They created the Kluane Game Sanctuary in 1943 on their side of the border. This later became Kluane National Park. These actions inspired the U.S. Interior Department to discuss similar parks in Alaska.

In 1964, George B. Hartzog Jr., director of the National Park Service, started a new study. He wanted to develop and promote Alaska's existing parks. Further actions by the Park Service in the late 1960s led to a master plan. By 1969, the Interior Department suggested that the Bureau of Land Management oversee a large "Wrangell Mountain Scenic Area." This plan would allow resource development along with preservation and recreation. The Park Service didn't like this idea.

The 1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) led to new proposals for Alaska parks. This act required setting aside 80 million acres of land for conservation. The National Park Service suggested a 15-million-acre Alaska National Park in the Wrangell Mountains. The Interior Secretary later cut the proposed area. Later changes brought the proposed acreage back up. A smaller park of 8.64 million acres was proposed in 1973. Competing bills were written in 1974 by groups wanting both preservation and development.

A variety of bills were introduced in Congress in 1976. None passed, but one bill introduced the idea of national preserves. These would have most of the protections of national parks but would allow hunting. In 1977, Representative Morris K. Udall introduced the first version of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA). This bill proposed a 14-million-acre Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and a 1.8-million-acre Chisana National Preserve. Although the Park Service supported it, Alaska opposed the bill. A revised bill was proposed, with 9.6 million acres in national park lands and 2.49 million acres in an adjoining preserve. Both were to be named Wrangell–St. Elias. Hearings in 1978 adjusted the areas and boundaries. This was done to allow hunting of Dall sheep in the Wrangell Mountains.

Alaska senator Mike Gravel stopped the proposed ANILCA bill. After this, and with Alaska trying to claim lands within the proposed protected areas, President Jimmy Carter used the Antiquities Act. He declared 17 Alaskan national monuments, including 10.95 million acres in Wrangell–St. Elias National Monument, on December 1, 1978.

The monument designation didn't come with money for park development. But it caused a lot of anger from Alaskans. They saw it as the federal government taking their land. The few Park Service staff in the area received threats. A Park Service airplane was destroyed by fire in August 1979. People were very divided. White Alaskans were mostly against the park. Native Ahtnas, however, were granted hunting rights for food and hoped to benefit from tourism.

The Park and Preserve Today

In January 1979, Udall introduced a changed version of the bill. After discussions, the bill was approved on November 12. On December 2, 1980, President Jimmy Carter signed the ANILCA bill into law. This made Wrangell–St. Elias a national park and preserve. It started with 8.147 million acres in the park and 4.171 million acres in the preserve. The boundaries between the park and preserve were drawn based on scenery versus hunting potential. The law also set aside 9.66 million acres as wilderness.

Some Alaskans continued to oppose the park after it was officially created. They didn't like the federal government's presence, especially the National Park Service. Vandalism continued, with a ranger cabin burned and an airplane damaged. People also ignored rules and complained about what they saw as an "elitist" attitude from the park. However, relations improved for a while. Local businesses promoted the park and worked with the Park Service on tourism. Incidents still happened, like arson at a ranger station. Relations got worse again in 1994 when the park superintendent testified for more funding. This was seen by residents as confirming their suspicions about the Park Service. This was the peak of resentment against the park. After this, local residents started taking part in Park Service events. Still, the 1979 designation of the region as a UNESCO World Heritage Site continued to be viewed with suspicion by some.

The state of Alaska suggested big improvements to the McCarthy Road in 1997. They planned to pave it and add scenic pull-offs. Although the road is still gravel, it has been widened and smoothed. Some car rental companies still don't allow their vehicles on the McCarthy Road.

Special Designations for the Park

The transborder park system, Kluane / Wrangell–St. Elias / Glacier Bay / Tatshenshini-Alsek, was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979. This was because of its amazing glaciers and icefields. It was also recognized for being important habitat for grizzly bears, caribou, and Dall sheep. When the park was established in 1980, 9.078 million acres of the park and preserve were named the Wrangell–Saint Elias Wilderness. This is the largest single wilderness area in the United States.

Park Climate and Weather

The park's interior has long, cold winters. Temperatures can stay below freezing for five months. Nighttime lows can drop to -50°F (-45°C). Daytime highs are usually around 5°F to 7°F (-15°C to -14°C). Summer lasts two months, June and July. It brings flowers and biting insects, with high temperatures of 80°F (27°C). Late summers can be rainy. It starts to get cool in August, and the first snow falls in September. Conditions are milder along the coast. The high mountains keep snow all year.

The park has three main climate types:

- Continental Subarctic - Cold Dry Summer (Dsc): This climate has cold winters, with the coldest month below 32°F (0°C). Summers are cool, with 1-3 months above 50°F (10°C). Winter has much more rain than summer.

- Subarctic With Cool Summers And Dry Winters (Dwc): The coldest month is below 32°F (0°C). Summers are cool, with 1-3 months above 50°F (10°C). Most of the yearly rain falls in the warmest six months.

- Subarctic With Cool Summers And Year Around Rainfall (Dfc): The coldest month is below 32°F (0°C). Summers are cool, with 1-3 months above 50°F (10°C). There isn't a big difference in rainfall between seasons.

The Kennecott Visitor Center is in Plant Hardiness zone 3a. This means the average lowest temperature in winter is -37.8°F (-38.8°C).

Park Ecology: Plants and Animals

Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve is larger than Switzerland. It stretches from the Gulf of Alaska to Alaska's interior. Its altitudes range from sea level to 19,000 feet. Because of this, it has many different habitats. Much of the park is high mountain peaks covered with ice and glaciers. Rivers flow in wide, flat glacial valleys. The environment can be divided into five main types: lowlands, wetlands, uplands, sub-alpine, and alpine. Some areas are affected by permafrost, which is permanently frozen ground.

Plant Communities in the Park

The lowland areas of the park are along the Gulf of Alaska and in the lower river valleys. Black spruce trees grow in areas with permafrost. Underneath them are plants like alder, Labrador tea, willows, and blueberry, along with different ground mosses.

Wetlands can be found along the coast and in the interior river basins. Permafrost areas are often marshy. These wetland areas are mostly grassy, with sedges and small shrubs. Horsetails and spikerush are also found here.

The drier forested upland parts of the park are mostly boreal forest, also called taiga. How different tree species are spread depends on how often fires happen. The most common evergreen trees are Black spruce and larger white spruce. White spruce is more common in areas without permafrost. Black spruce are better at surviving fires. Both quaking aspen and paper birch are common deciduous trees. They are usually the first trees to grow after a fire. Then come balsam poplar and eventually white spruce.

Subalpine environments are above the local tree line. In Wrangell–St. Elias, this is usually between 3,600 feet and 5,600 feet. Plants here are low and slow-growing shrubs, mostly grasses and other small flowering plants.

The alpine environment changes depending on how much water is available. It starts at different heights, from 3,600 feet in dry areas to 4,600 to 5,900 feet in wetter areas. Heaths and low-growing willows are common, along with other small flowering plants.

Wildlife in the Park

Large land mammals in the park include timber wolfes, grizzly bears, black bears, and caribou. Mountain goats and Dall sheep live in the mountains. About 13,000 Dall sheep live in Wrangell–St. Elias. This is one of the largest groups of this animal in North America. Moose are not common but can sometimes be found where willows grow.

Smaller mammals include wolverines, beavers, Canadian lynxes, porcupines, martens, river otters, red foxes, coyotes, ground and flying squirrels, hoary marmots, weasels, snowshoe hares, and pikas. A few bison have been introduced in two herds in the park. Cougars are thought to be possible but haven't been officially seen. The waters along the coast are home to whales, porpoises, harbor seals, and sea lions. The endangered Steller sea lion can be found in the park's waters.

Twenty-one types of fish have been found in the park's freshwaters. Fish distribution depends on the river system. For example, northern pike are not seen in the Copper River. No salmon species are seen in the Yukon River systems. Large freshwater fish include Chinook, chum, coho, pink, and sockeye salmon. Other salmon-like fish include lake trout, cutthroat trout, Dolly Varden, Arctic grayling, and rainbow trout. Other fish include eulachon, burbot, round whitefish, Pacific lamprey, and various sculpins.

About 93 species of birds live in Wrangell–St. Elias, but only 24 stay during the harsh winter. The most common birds include willow and rock ptarmigan, Canada jays, ravens, hermit thrushes, American robins, hairy woodpeckers, and northern flickers. Owls include great horned owls, northern hawk owls, and boreal owls.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Parque nacional y reserva Wrangell-San Elías para niños

In Spanish: Parque nacional y reserva Wrangell-San Elías para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |