History of Chinese cuisine facts for kids

The history of Chinese cuisine is full of amazing variety and constant changes. A scholar named Kwang-chih Chang once said that "Chinese people are especially preoccupied with food." He also noted that food is often at the heart of, or at least part of, many social gatherings. He believed that even with all the changes over time, the basic ideas behind Chinese food have stayed the same. A typical Chinese meal usually has grains or starches (traditional Chinese: 飯; simplified Chinese: 饭; pinyin: fàn) and other dishes made from vegetables or meat (Chinese: 菜; pinyin: cài).

Contents

How Chinese Food Changed Over Time

A historian named Endymion Wilkinson pointed out several big changes that made Chinese food so rich and always evolving:

- Growing Bigger: As Han Chinese culture spread from the Yellow River area to a huge geographical region, it included many different climates, from tropical to very cold. This brought new ingredients and local cooking styles into Chinese cuisine.

- Food as Medicine: Traditional Chinese medicine saw food as super important for good health. People believed that "Food was medicine and medicine, food."

- Demands from Important People: Rich and powerful people, like emperors, governors, wealthy landowners, and even traveling merchants, always wanted special dishes. This encouraged unique cooking styles to develop, no matter how far away they were from home.

- New Ideas from Far Away: Chinese cuisine kept absorbing new influences from other cultures. This included ingredients, cooking methods, and recipes from people like nomadic groups, European missionaries, and Japanese traders.

The writer Lin Yutang had a fun way of looking at it: "A Chinese person truly shines when enjoying a good meal! They are so likely to exclaim that life is beautiful when their stomach is full! From this full stomach comes a happiness that feels spiritual. The Chinese trust their instincts, and their instincts tell them that when the stomach is happy, everything is happy. That's why I say the Chinese live closer to their instincts and have a philosophy that openly celebrates it."

Chinese cuisine as we know it today slowly developed over centuries. New foods and cooking techniques were found, invented, or brought in. Some important features of Chinese food appeared very early, while others became popular much later.

For example, the first chopsticks were probably used for cooking, stirring fires, and serving food, not for eating. They started being used as eating tools during the Han dynasty. But it wasn't until the Ming dynasty that they became common for both serving and eating. They also got their current name (筷子, kuaizi) and shape during the Ming period.

The wok might have also appeared during the Han dynasty, but at first, it was only used for drying grains. Its main use today—for stir-frying, boiling, steaming, roasting, and deep-frying—didn't develop until the Ming dynasty. The Ming period also saw new plants from the Americas, like maize (corn), peanuts, and tobacco. Wilkinson said that "somebody brought up on late twentieth century Chinese cuisine, Ming food would probably still seem familiar, but anything further back, especially pre-Tang would probably be difficult to recognize as 'Chinese'."

The "Silk Road" was a famous network of trade routes through Central Asia that connected the Iranian plateau with western China. Along these routes came exciting new foods that greatly expanded Chinese cooking. Many Chinese cooks might be surprised to learn that some of their basic ingredients originally came from other countries. For example, sesame, peas, onions, coriander, and cucumber were all brought to China from the West during the Han dynasty.

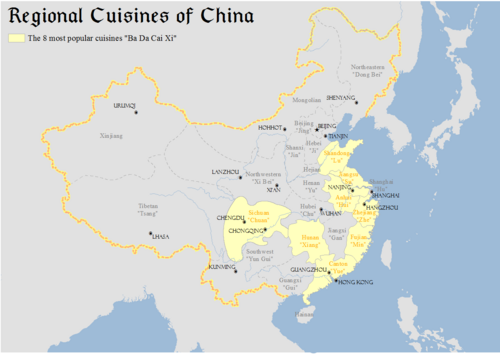

Types of Chinese Food

After the Chinese Empire grew during the Qin dynasty and Han dynasty, writers noticed big differences in how people cooked in different parts of the country. These differences were largely because of the different climates and foods available. Many people tried to classify these cooking styles. However, because political borders changed and cultures mixed, it was hard to create clear, lasting categories. Even small ethnic groups had their own cuisines, which were included in early lists. Still, some general categories are helpful:

Northern and Southern Cuisine

The first and most important difference was between the older, drier North China Plain and the rainier, hilly land south of the Yangtze River. The southern areas became part of the Chinese empire much later. Today, canals, railroads, and highways have made these differences less clear. However, it's still true that rice is the main food in southern cooking, while flour products (like different noodles and dumplings) are more common in the north.

Four Main Cooking Styles

The "Four Schools" refer to the cooking styles of Shandong (called Lu), Jiangsu (called Yang), Cantonese (called Yue), and Sichuan (called Chuan).

The cooking styles of other areas were then grouped under these four:

| Lu (Shandong) | Yang (Su) | Yue (Guangdong/Cantonese) | Chuan (Sichuan) |

|---|---|---|---|

Eight Main Cooking Styles

Eventually, four of these branches became recognized as their own distinct Chinese cooking styles: Hunan (called Xiang), Fujian (called Min), Anhui (Hui), and Zhejiang (Zhe).

History of Chinese Food

Ancient Times (Neolithic Period)

Even though there are no written records from this very old time, archaeologists can guess how food was prepared and stored by looking at ancient sites. Sometimes, they even find old tools or very rarely, preserved food. In 2005, the oldest noodles ever found were discovered at the Lajia site in Qinghai, near the Yellow River. These noodles were over 4,000 years old and made from foxtail millet and Proso millet.

Early Dynasties

Legends say that Shennong taught people how to farm and first grew the "Five Grains." The list of these grains changed over time, but often included seeds like hemp and sesame used for oils and flavor. The Classic of Rites lists soybeans, wheat, broomcorn and foxtail millet, and hemp. A Ming dynasty writer, Song Yingxing, correctly noted that rice wasn't originally one of the Five Grains grown by Shennong. This is because southern China, where rice grows best, hadn't been settled by the Han Chinese yet. However, many later lists of the Five Grains do include rice.

During the Han dynasty, common staple foods were wheat, barley, rice, foxtail and broomcorn millet, and beans. People often ate fruits and vegetables like chestnuts, pears, plums, peaches, melons, apricots, red bayberries, jujubes, calabash, bamboo shoots, mustard greens, and taro. They also ate domesticated animals such as chickens, Mandarin ducks, pigs, geese, sheep, camels, and even dogs. Fish and turtles were caught from rivers and lakes. Wild animals like owls, pheasants, magpies, sika deer, and Chinese bamboo partridge were hunted. For seasoning, they used sugar, honey, salt, and soy sauce. Beer and yellow wine were common, but baijiu (a strong liquor) came much later.

During the Han dynasty, Chinese people developed ways to preserve food for soldiers, like drying meat into jerky and cooking, roasting, and drying grains.

Chinese legends say that the roasted, flat shaobing bread was brought from Central Asia by the Han dynasty General Ban Chao. It was first called "barbarian pastry." The shaobing is thought to be related to the Persian and Central Asian naan and the Middle Eastern pita bread. During the Tang dynasty, people from Central Asia made and sold sesame cakes in China.

Southern and Northern Dynasties

During the Southern and Northern Dynasties, non-Han people like the Xianbei of Northern Wei introduced their food to northern China. This influence continued into the Tang Dynasty, making meats like mutton and dairy products like goat milk, yogurts, and kumis popular even among Han people. However, during the Song dynasty, Han Chinese started to dislike dairy products and stopped eating them. A Han Chinese rebel named Wang Su, who fled to the Xianbei Northern Wei, at first couldn't eat dairy or mutton. He preferred tea and fish. But after a few years, he enjoyed yogurt and lamb. A text from this period, the Qimin Yaoshu, contains 280 recipes.

Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD)

People in the Tang dynasty loved exotic foods from their vast empire and searched for plants and animals that could improve health and help them live longer. These interests led to a wide variety of foods. Besides those already mentioned, common foods and ingredients included barley, garlic, salt, turnips, soybeans, pears, apricots, peaches, apples, pomegranates, jujubes, rhubarb, hazelnuts, pine nuts, chestnuts, walnuts, yams, and taro.

They ate various meats like pork, chicken, lamb (especially popular in the north), sea otter, bear (which was hard to catch, but there were recipes for it), and even Bactrian camels. Along the southern coast, seafood was very common. Chinese people enjoyed cooked jellyfish with cinnamon, Sichuan pepper, cardamom, and ginger. They also ate oysters with wine, fried squid with ginger and vinegar, horseshoe crabs, red crabs, shrimp, and pufferfish (which they called 'river piglet').

Some foods were not allowed. The Tang court encouraged people not to eat beef because bulls were valuable for farm work. From 831 to 833, Emperor Wenzong of Tang even banned killing cattle because of his Buddhism beliefs. Through trade, the Chinese got golden peaches from Samarkand, date palms, pistachios, and figs from Persia, pine seeds and ginseng roots from Korea, and mangoes from Southeast Asia.

There was a huge demand for sugar in China. During the reign of Harsha (606–647) in North India, Indian visitors to Tang China brought two sugar makers who successfully taught the Chinese how to grow sugarcane. Cotton also came from India as a finished product. Although the Chinese started growing and processing cotton during the Tang dynasty, it became the main fabric in China by the Yuan Dynasty.

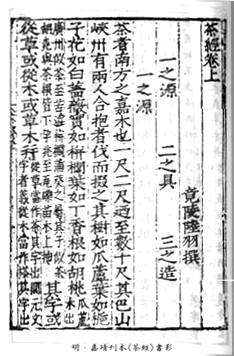

During the earlier Southern and Northern Dynasties, and maybe even before, drinking tea became popular in southern China. Tea comes from the leaf buds of the Camellia sinensis plant, which is native to southwestern China. Tea was seen as a pleasant drink and also believed to have medicinal benefits. In the Tang Dynasty, tea became a symbol of sophistication. The Tang poet Lu Tong (790–835) wrote many poems about his love for tea. The 8th-century writer Lu Yu, known as the Sage of Tea, even wrote a book about tea called the Classic of Tea (Chájīng). Tea was also enjoyed by Uyghur Turks, who would visit tea shops first when they rode into town. While wrapping paper had been used in China since the 2nd century BC, during the Tang Dynasty, the Chinese used wrapping paper as folded and sewn square bags to hold and keep the flavor of tea leaves.

Ways to preserve food continued to improve. Ordinary people used simple methods like digging deep ditches, brining, and salting their food. The emperor had large ice pits in parks around Chang'an to preserve food. Wealthy people had their own smaller ice pits. Each year, the emperor had workers carve 1000 blocks of ice from frozen creeks in mountain valleys. These blocks were about 3 feet by 3 feet by 3.5 feet. Many chilled treats, especially chilled melon, were enjoyed during the summer.

Liao, Song, and Jurchen Jin Dynasties (907–1234 AD)

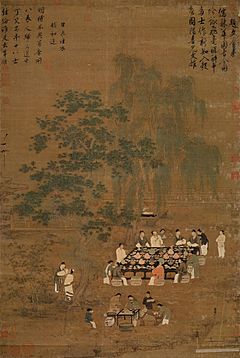

The Song dynasty was a major turning point for Chinese food. Big changes in business and farming led to a larger group of wealthy city dwellers who had access to many cooking techniques and ingredients. For these people, eating became a thoughtful and enjoyable experience. Food historian Michael Freeman says that the Song dynasty developed a "cuisine" that combined the best of several traditions. This kind of "cuisine" needs many adventurous eaters who are willing to try new foods, not just stick to what they know from their hometown. It's about truly enjoying food, not just its traditional meaning. This was different from the formal court food or simple country cooking. This is what we now think of as "Chinese food."

In the Song dynasty, we find clear evidence of restaurants. These were places where customers could choose from a menu, unlike taverns where they had no choice. These restaurants offered regional dishes. Food lovers wrote about their favorite dishes, showing that food and eating had become an art form. These developments in the Song dynasty happened much later in Europe.

We have lists of dishes from restaurant menus and banquets, especially from a book called Dongjing Meng Hua Lu (Dreams of Splendor of the Eastern Capital). Many of the strange names for these dishes don't tell us what ingredients were used. However, scholar Jacques Gernet believes that the food in Hangzhou was similar to today's Chinese food, based on the seasonings used, like pepper, ginger, soya sauce, oil, salt, and vinegar. Other seasonings included walnuts, turnips, crushed Chinese cardamom kernels, fagara, olives, ginkgo nuts, citrus zest, and sesame oil.

Different regions had different cooking styles because of their environment and culture. During the Southern Song dynasty, people fleeing from the north brought their cooking traditions, like Henan-style food, to the new capital at Hangzhou. This mixed with the local cooking styles of Zhejiang.

Even in the Northern Song capital of Kaifeng, there were restaurants that served southern Chinese food. These were for officials from the southeast who found northern food too plain. Song-era documents are the first to use phrases like nanshi (southern food), beishi (northern food), and chuanfan (Sichuan food). Restaurants were known for their specialties. For example, one restaurant in Hangzhou only served iced foods, while others offered hot, warm, room temperature, or cold dishes. Descendants of Kaifeng restaurant owners ran most of the restaurants in Hangzhou, but many other regional styles were also available. This included restaurants with spicy Sichuan cuisine and taverns with dishes and drinks from Hebei and Shandong, as well as seafood from the coast. Waiters in larger restaurants had to have excellent memory and patience, as dinner parties with twenty or more dishes could be tricky. If a guest complained, the waiter could be punished or even fired.

Along the main Imperial Way in Hangzhou, special breakfast items and treats were sold in the morning. These included fried tripe, pieces of mutton or goose, various soups, hot pancakes, steamed pancakes, and iced cakes. Noodle shops were also popular and stayed open all day and night along the Imperial Way. Night markets closed late but reopened early, and were known for staying open even during winter storms.

Foods from other countries also came to China, such as raisins, dates, Persian jujubes, and grape wine. The traveler Marco Polo noted that rice wine was more common than grape wine. Although grape wine had been known in China since the Han dynasty, it was mostly for the rich. Other drinks included pear juice, lychee fruit juice, honey and ginger drinks, tea, and pawpaw juice. Dairy products, which were common in the Tang dynasty, became linked to foreign cultures, which is why cheese and milk were not common in their diet. Beef was also rarely eaten because cows were important for farm work. The main diet for poorer people was rice, pork, and salted fish. While restaurant menus didn't show dog meat, wealthy people ate a variety of wild and farm animals, like chicken, shellfish, fallow deer, hare, partridge, pheasant, francolin, quail, fox, badger, clam, and crab. Freshwater fish from the nearby lake and river were also sold, and West Lake provided geese and duck. Common fruits included melons, pomegranates, lychees, longans, golden oranges, jujube, quince, apricots, and pears. In the Hangzhou area alone, there were eleven kinds of apricots and eight kinds of pears.

Special dishes included scented shellfish cooked in rice-wine, geese with apricots, lotus seed soup, spicy soup with mussels and fish cooked with plums, sweet soya soup, baked sesame buns stuffed with sour bean filling or pork, mixed vegetable buns, candied fruit, ginger strips, jujube-stuffed steamed dumplings, fried chestnuts, and 'honey crisps' made from honey, flour, mutton fat, and pork lard. Desserts shaped like girls' faces or soldiers were called "likeness foods."

Su Shi, a famous poet and official, wrote a lot about the food and wine of his time. His love for food is still remembered in a dish called Dongpo pork, named after him. An important book from this period, Shanjia Qinggong (The Simple Foods of the Mountain Folk) by Lin Hong, describes how to make many common and fancy dishes. Eating habits changed a lot during this time, with ingredients like soy sauce and Central Asian-influenced foods becoming widespread. Important cookbooks like Shanjia Qinggong and Wushi Zhongkuilu show the special and everyday foods of the time.

Mongol Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368 AD)

During the Yuan dynasty, contact with the West brought a new major food crop to China: sorghum. Other foreign foods and cooking methods also arrived. Hu Sihui, a Mongol doctor of Chinese medicine, wrote Yinshan Zhengyao, a guide to cooking and health that combined Chinese and Mongol food practices. The recipes were written in a clear way, with step-by-step instructions for ingredients and cooking methods. Yunnan cuisine in China is unique for its cheeses like Rubing and Rushan cheese, made by the Bai people, and its yogurt. This yogurt might be due to a mix of Mongolian influence during the Yuan dynasty, Central Asian people settling in Yunnan, and the closeness of India and Tibet.

Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 AD)

During the Ming dynasty, China became part of a new global trade of goods, plants, animals, and food crops, known as the Columbian Exchange. While most imports to China were silver, the Chinese also bought new crops from the Spanish Empire. These included sweet potatoes, maize (corn), and peanuts. These foods could grow in lands where traditional Chinese staple crops—wheat, millet, and rice—couldn't. This helped the population of China grow. In the Song Dynasty, rice had become the main food for poorer people. After sweet potatoes were brought to China around 1560, they slowly became a traditional food for the lower classes.

Qing Dynasty (1644–1912 AD)

Jonathan Spence wrote that by the Qing Dynasty, "culinary arts were treated as a part of the life of the mind." This means that cooking was seen as an intellectual pursuit, like philosophy or writing. There was a "Tao of food," just like there was a "Tao of conduct." The rich official Li Liweng loved luxury, while the food expert Yuan Mei preferred simplicity. To make the best rice, Li would send his maid to collect dew from wild rose, cassia, or citron flowers to add at the last minute. Yuan Mei, on the other hand, was a more humble food lover. In his food book, Suiyuan shidan, he wrote: "I always say that chicken, pork, fish, and duck are the true stars of the table. Each has its own flavor and style. But expensive foods like sea-slug and swallows-nest are common and have no character—they're just fillers. Once, a Governor invited me to a party and served plain boiled swallows-nest in huge vases, like flower pots. It had no taste at all.... If his goal was just to impress, it would have been better to put a hundred pearls into each bowl. Then we would have known the meal cost a fortune, without the unpleasantness of being expected to eat something uneatable." After such a meal, Yuan said he would go home and make himself a simple bowl of congee (rice porridge).

Records from the Imperial Banqueting Court in the late Qing period show there were different levels of Manchu banquets and Chinese banquets. The royal Manchu–Han Imperial Feast was a famous meal that combined both traditions.

The special dish Dazhu gansi was highly praised by the Qing emperor Qianglong.

After the Dynasties

After the Qing dynasty ended, cooks who used to work in the Imperial Kitchens opened restaurants. This allowed ordinary people to try many of the special foods once only eaten by the Emperor and his court. However, when the Chinese Civil War began, many cooks and people knowledgeable about Chinese cuisine left for Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the United States. Among them was Irene Kuo, who helped introduce the refined aspects of Chinese cuisine to the Western world.

After the founding of the People's Republic of China, the nation faced some major food supply challenges. Some parts of China, especially in the countryside, faced tough times with food. By January 1959, food became very scarce in cities like Beijing. Many farmers struggled to find enough to eat, even as they had to give food to the government. Starting in 1960, a period of great food shortages, sometimes called the Great Chinese Famine, made things even harder. During this time, there was little progress in cooking traditions. Many people fled to nearby Hong Kong and Taiwan to avoid starvation.

| Year | Percent of grain handed over to the Communist party |

|---|---|

| 1957 | 24.8% |

| 1959 | 39.6% |

| 1960 | 35.7% |

In Beijing in the 1990s, a style of food called Cultural Revolution cuisine or CR cuisine became popular. Another recent trend was Retro-Maoist cuisine, which became popular around the 100th anniversary of Mao Zedong's birthday. The menu included simple items like cornmeal cakes and rice gruel. In February 1994, The Wall Street Journal wrote an article about Retro-Maoist cuisine being a hit in China. Owners of a CR-style restaurant said, "We're not nostalgic for Mao, per se. We're nostalgic for our youth." The Chinese government has said it was not involved with Retro-Maoist cuisine.

One type of food that benefited in the 1990s was Chinese Islamic cuisine. The foods of other cultures in China have also benefited from recent changes in government policy. During the 1970s, the government encouraged the Hui people to adopt Han Chinese culture. Since then, the national government has stopped trying to make all Chinese cultures the same. To bring back their unique food, the Huis started labeling their dishes as "traditional Hui cuisine." This effort has been successful. For example, in 1994, "Yan's family eatery" earned a good income each month, which was much higher than the average salary at that time.

Crocodiles were eaten by Vietnamese people, but they were considered forbidden for Chinese people. Vietnamese women who married Chinese men adopted this Chinese custom.

Famous Sayings About Chinese Food

A common saying tries to sum up Chinese cuisine in one sentence. While it's a bit old-fashioned now (as Hunan cuisine and Sichuan cuisine are very famous for their spicy food even in China), many versions have appeared:

| Language | Phrase |

|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 東甜,南鹹,西酸,北辣 |

| Simplified Chinese | 东甜,南咸,西酸,北辣 |

| English | The East is sweet, the South's salty, the West is sour, the North is hot. |

| Pinyin | Dōng tián, nán xián, xī suān, běi là. |

| Jyutping | Dung1 tim4, naam4 haam4, sai1 syun1, bak1 laat6*2. |

Another popular traditional phrase talks about regional strengths and highlights Cantonese cuisine as a favorite:

| Language | Phrase |

|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 食在廣州,穿在蘇州,玩在杭州,死在柳州 |

| Simplified Chinese | 食在广州,穿在苏州,玩在杭州,死在柳州 |

| English | Eat in Guangzhou, clothe in Suzhou, play in Hangzhou, die in Liuzhou. |

| Pinyin | Shí zài Guǎngzhōu, chuān zài Sūzhōu, wán zài Hángzhōu, sǐ zài Liǔzhōu. |

| Cantonese | Sik joi Gwongjau, chuen joi Sojau, waan joi Hongjau, sei joi Laujau. |

The other parts of this saying praise Suzhou's silk industry and tailors, Hangzhou's beautiful scenery, and Liuzhou's forests. The fir trees from Liuzhou were valued for making coffins in traditional Chinese burials before cremation became popular. Different versions of this saying exist, but they usually keep the same focus for Canton and Guilin. Sometimes they suggest 'playing' in Suzhou (which is famous for its traditional gardens and beautiful women) and 'living' in Hangzhou.

|