History of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1648) facts for kids

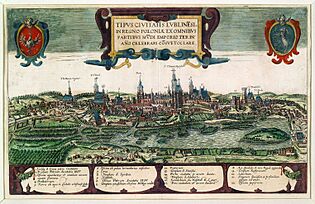

The history of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1648) tells the story of Poland and Lithuania when they were united as one big country. This period came before a time of very destructive wars in the mid-1600s. The Union of Lublin in 1569 created the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. This was a new, more unified federal state, replacing an older, looser connection between the two countries.

The Commonwealth was mostly run by the Polish and Polonized Lithuanian and Ruthenian nobility. They used a system with a central parliament and local assemblies. From 1573, the country was led by elected kings. This rule by the nobility was quite unique. It was an early form of democracy, especially when most other European countries had absolute monarchs.

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth became a powerful player in Europe. It was also a very important cultural center. In the late 1500s and early 1600s, it was a huge state in central-eastern Europe. Its area was almost one million square kilometers.

After the Reformation, the Commonwealth had amazing religious tolerance. The Warsaw Confederation of 1573 was a great example of this. But then, the Catholic Church started a strong counter-movement called the Counter-Reformation. Many people who were Protestants became Catholics again. There were also growing problems with the eastern Ruthenian people in the Commonwealth. These issues led to the Union of Brest, which divided the Eastern Christians. On the military side, there were many Cossack uprisings.

The Commonwealth was strong militarily under King Stephen Báthory. But it faced problems during the reigns of the Vasa kings, Sigismund III and Władysław IV. The country also had internal fights. Kings, powerful magnates (rich nobles), and different noble groups were often in conflict. The Commonwealth fought wars with Russia, Sweden, and the Ottoman Empire. When the Commonwealth was at its strongest, some of its neighbors had their own troubles. Poland-Lithuania tried to become the main power in Eastern Europe, especially over Russia. It was allied with the Habsburg monarchy and did not directly join the Thirty Years' War.

In 1577, Tsar Ivan IV of Russia started fighting in the Livonia region. He took over most of the area. This brought Poland-Lithuania into the Livonian War. King Báthory and Jan Zamoyski led a successful counter-attack. This led to the peace of 1582. They took back much of the land from Russia. Swedish forces took control of the far north (Estonia). Sigismund III declared Estonia part of the Commonwealth in 1600. This started a war with Sweden over Livonia. The war lasted until 1611 but did not have a clear winner.

In 1600, Russia entered a period of great instability. The Commonwealth suggested joining with Russia. This failed, and many other attempts followed. Some involved military invasions. Others involved tricky dynastic and diplomatic plans. In the end, the differences between the two societies were too big. However, after the Truce of Deulino in 1619, the Polish-Lithuanian state reached its largest size ever. But this huge military effort also weakened it.

In 1620, the Ottoman Empire under Sultan Osman II declared a war against the Commonwealth. At the terrible Battle of Ţuţora (1620), Hetman Stanisław Żółkiewski was killed. The Commonwealth was in a very dangerous situation against the Turkish and Tatar invaders. Poland-Lithuania gathered its forces. Hetman Jan Karol Chodkiewicz's army bravely fought off strong enemy attacks at the Battle of Khotyn (1621). This improved the situation on the southeastern front. More wars with the Ottomans happened in 1633–1634. Large parts of the Commonwealth were raided by Tatars, who took many people as slaves.

War with Sweden started again in 1621. Now under Gustavus Adolphus, Sweden attacked Riga. They then occupied much of Livonia. They controlled the Baltic Sea coast up to Puck and blocked Gdańsk (Danzig). The Commonwealth was tired from other wars. In 1626–1627, it fought back. Hetman Stanisław Koniecpolski showed great military skill, and Austria also helped. Several European powers pushed for peace. The fighting stopped with the Truce of Altmark. This left much of Gustavus Adolphus's conquests in Swedish hands.

Another war with Russia happened in 1632. It ended without much change. King Władysław IV then tried to get back the lands lost to Sweden. At the end of the fighting, Sweden left the cities and ports of Royal Prussia. But they kept most of Livonia. Courland, which stayed with the Commonwealth, handled Lithuania's Baltic trade. After Frederick William's last Prussian homage to the Polish king in 1641, the Commonwealth's power over Prussia and its Hohenzollern rulers kept getting weaker.

Contents

- Electing Kings and Noble Rule

- Economy and Society

- Christianity in the Commonwealth

- Early Baroque Culture

- Parliament and Local Assemblies

- Noble Rule and First Royal Election

- Stephen Báthory's Rule

- War with Russia over Livonia

- Sigismund III Vasa's Reign

- Cossacks and Rebellions

- Władysław IV's Reign

- Seeking Power in Eastern Europe

- Moldavia

- War with Sweden

- Attempts to Control Russia

- Commonwealth and the Thirty Years' War

- Conflicts with the Ottoman Empire and Crimean Khanate

- Losses of Baltic Territory and Sea Access

- Weakened Power

- See also

Electing Kings and Noble Rule

When the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth began in the late 1500s, Poland–Lithuania became a country where the king was chosen by election. The nobility would vote for their king. This king would rule until he died, and then a new election would be held. This system was often called a rzeczpospolita or republic. This was because the noble classes had a lot of power and influence.

In 1572, Sigismund II Augustus, the last king from the Jagiellonian dynasty, died without children. The political system was not ready for this. There was no clear way to pick a new king. After much discussion, it was decided that all the nobility of Poland and Lithuania would choose the next king. The nobles gathered at Wola, near Warsaw, to vote in the royal election.

The election of Polish kings continued until the Partitions of Poland. Some of the elected kings included Henry of Valois, Stephen Báthory, Sigismund III Vasa, and Władysław IV.

The first Polish royal election happened in 1573. Four men ran for king. They were Henry of Valois (brother of the French King), Tsar Ivan IV of Russia, Archduke Ernest of Austria, and King John III of Sweden. Henry of Valois won. But he only served as Polish king for four months. He heard that his brother, the King of France, had died. So, Henry of Valois left Poland and went back to France to become Henry III of France.

Some elected kings left a big mark on the Commonwealth. Stephen Báthory tried to make the king's power stronger. Sigismund III, Władysław IV, and John Casimir were all from the Swedish House of Vasa. They were often busy with foreign and family matters. This kept them from helping Poland-Lithuania become more stable. John III Sobieski led the allied forces at the Battle of Vienna in 1683. This was the last great victory for the Commonwealth. Stanisław August Poniatowski, the last Polish king, was a complex figure. He pushed for important reforms. But his weakness, especially with imperial Russia, led to the failure of these reforms and the country's downfall.

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, after the Union of Lublin, was very different from the absolute monarchies growing in Europe. Its almost-democratic political system, called Golden Liberty, was unique. Even though only nobles could vote, it was a big step for future constitutional monarchies in Europe.

However, there were many power struggles. The lesser nobility (szlachta), the richer nobles (magnates), and the elected kings often fought. This weakened the government's power and its ability to defend the country. The famous liberum veto rule was used to stop parliament meetings from the mid-1600s. After many terrible wars in the mid-1600s (like the Chmielnicki Uprising and the Deluge), Poland-Lithuania lost its influence in Europe. During these wars, the Commonwealth lost about one-third of its people. Its economy was also hurt because nobles relied on agriculture and serfdom. This, along with a weak city-dwelling class, slowed down the country's industrial growth.

By the early 1700s, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was one of Europe's largest countries. But it became a pawn for its neighbors: the Russian Empire, Prussia, and Austria. These neighbors often interfered in its politics. In the late 1700s, the Commonwealth was repeatedly divided by these powers and stopped existing.

Economy and Society

The boom in agricultural trade in Eastern Europe started to slow down in the 1580s. Food prices stopped rising. Then, prices for farm products slowly went down. This price depression first appeared in Western Europe. It badly affected the folwark economies in the East, especially in the mid-1600s. The economy got worse around 1620. This was due to a Europe-wide devaluation of money, caused by a lot of silver coming from the Americas. But even then, huge amounts of Polish grain were still sent out through Gdańsk (Danzig). The Commonwealth nobility tried to fight the crisis. They kept production high by putting more burdens on the serfs. Nobles also forcibly bought or took over lands from richer peasants, especially from the mid-1600s.

Money and effort from city business owners helped mining and metalwork grow early in the Commonwealth's history. There were hundreds of hammersmith shops around 1600. Large ironworks furnaces were built in the early 1600s. Silver, copper, and lead mining also grew. Salt production expanded in Wieliczka, Bochnia, and other places. After about 1700, landowners started taking over some industrial businesses. They used serf labor, which led to neglect and decline in the mid-1600s.

Gdańsk (Danzig) stayed mostly independent. It strongly protected its special status and control over foreign trade. The Karnkowski Statutes of 1570 gave Polish kings control over sea trade. But even Stephen Báthory, who used armed force against the city, could not make them follow these rules. Other Polish cities remained stable and rich through the first half of the 1600s. But wars in the mid-century ruined the city dwellers.

A strict legal system for social classes developed around the early 1600s. It was meant to stop people from moving between classes. But the nobility's goal of being a closed group was never fully met. Even peasants sometimes became nobles. Many later Polish szlachta families had such "unofficial" beginnings. The Szlachta found reasons for their dominant role in a special set of beliefs called sarmatism.

The Union of Lublin sped up the process of Polonization. This meant that Lithuanian and Ruthenian leaders and nobles in Lithuania and the eastern borderlands started adopting Polish culture. This slowed down the national development of local people there. In 1563, Sigismund Augustus finally allowed Eastern Orthodox Lithuanian nobles to hold high offices. But by then, it didn't change much. Few Orthodox nobles were left, and the growing Catholic Counter-Reformation soon canceled these gains. Many rich noble families in the east were of Ruthenian origin. Their inclusion in the larger Crown made the magnate class much stronger. Regular szlachta, increasingly controlled by large landowners, did not want to join with Cossack settlers in Ukraine. They could have used them to balance the magnates' power. Instead, they offered late and ineffective half-measures regarding Cossack acceptance and rights. Peasants faced heavier burdens and more oppression. Because of these reasons, the way the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth grew caused more social and national tensions. This led to instability and future problems for the "Republic of Nobles."

Christianity in the Commonwealth

Most of the nobility in the Commonwealth, who were becoming more Polish, returned to the Roman Catholic faith during the 1600s. Or, if they were already Catholic, they stayed Catholic.

The Sandomierz Agreement of 1570 was an early example of Protestant peace-making. It was made because the Counter-Reformation was getting stronger. This agreement helped Protestants and made the Warsaw Confederation religious freedom guarantees possible in 1573.

At the peak of the Reformation in the Commonwealth, around the late 1500s, there were about a thousand Protestant churches. Almost half of them were Calvinist. Fifty years later, only half of them were left. City-dwelling Lutheranism suffered fewer losses. Calvinism and Nontrinitarianism (Polish Brethren) among the nobility suffered the most. The closing of the Brethren's Racovian Academy and a printing press in Raków in 1638, for charges of blasphemy, hinted at more trouble to come.

This Counter-Reformation happened somewhat strangely in a country with no religious wars. The state did not work with the Catholic Church to get rid of other religions. Reasons for this shift included low Protestant involvement among common people, especially peasants. Also, the kings were pro-Catholic. Nobles lost interest once they gained religious freedom. And the Catholic Church's propaganda became very strong.

The religious debate at first made the Commonwealth's intellectual life richer. The Catholic Church responded by reforming itself. It followed the rules of the Council of Trent, which the Polish Church accepted in 1577. But these rules were not fully put into practice until after 1589 and throughout the 1600s. Earlier reform efforts came from lower clergy. From about 1551, Bishop Stanislaus Hosius (Stanisław Hozjusz) of Warmia was a lone but strong reformer among the Church leaders. Around 1600, many bishops educated in Rome took over Church management. Strict rules for clergy were put in place, and Counter-Reformation activities quickly grew.

Hosius brought the Jesuits to Poland. He founded a college for them in Braniewo in 1564. Many Jesuit schools and homes were set up in the following decades, often near Protestant centers. Jesuit priests were carefully chosen, well-educated, and came from both noble and city families. They quickly became very influential at the royal court. They also worked hard with all parts of society. Jesuit education and Counter-Reformation messages used many new media techniques. These were often made for specific audiences. They also used older, proven methods of humanist teaching. Preacher Piotr Skarga and Bible translator Jakub Wujek were important Jesuit figures.

Catholic efforts to win people over countered the Protestant idea of a national church. They did this by making the Catholic Church in the Commonwealth more Polish. They added many local elements to make it more appealing to the masses. The Church leaders agreed with this idea. The changes in the 1600s shaped Polish Catholicism for centuries.

The peak of Counter-Reformation activity was around 1600, in the early years of Sigismund III Vasa's (Zygmunt III Waza) reign. He worked with the Jesuits and other Church groups to strengthen his monarchy. The King tried to limit high offices to Catholics. Anti-Protestant riots happened in some cities. During the Sandomierz Rebellion of 1606, many Protestants supported the opposition against the King. Still, the large number of nobles returning to Catholicism could not be stopped.

Protestants failed to form an alliance with the Eastern Orthodox Christians. These were the people living in the eastern part of the Commonwealth. This contributed to the Protestants' decline. The Polish Catholic leaders saw a chance to unite with the Orthodox. Their goal was to bring the Eastern Rite Christians under the Pope's control. The Orthodox Church was seen as a security risk. This was because Eastern Rite bishops depended on the Patriarchate of Constantinople. Also, the Moscow Patriarchate was established in 1589. The Moscow Patriarchate then claimed power over Orthodox Christians in the Commonwealth. This worried many of them, making them consider joining the West. The idea of union had the support of King Sigismund III and the Polish nobility in the east. Opinions were divided among Orthodox church and lay leaders.

The Union of Brest was agreed upon in 1595–1596. It did not merge Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. Instead, it created the Slavic language liturgy Uniate Church. This became an Eastern Catholic Church, one of the Greek Catholic Churches (today the Ukrainian Greek Catholic and Belarusian Greek Catholic Churches). The new church kept most of its Eastern Rite traditions but accepted the Pope's authority. This compromise union had problems from the start. Despite initial agreements, Greek-Catholic bishops were not given seats in the Senate. And Eastern Rite participants did not get the full equality they expected.

The Union of Brest increased tensions among Belarusian and Ukrainian communities in the Commonwealth. The Orthodox Church remained the strongest religious force there. It added to existing ethnic and class divisions. This became another reason for internal conflicts that hurt the Republic. The Eastern Orthodox nobility, called "Disuniates" and losing legal standing, fought for their rights. Prince Konstanty Ostrogski led an Orthodox intellectual revival in Polish Ukraine. In 1576, he founded the Ostroh Academy, an elite school with teaching in three languages. In 1581, he and his academy helped publish the Ostroh Bible. This was the first scholarly Orthodox Church Slavonic edition of the Bible. Thanks to these efforts, laws in 1607, 1609, and 1635 recognized the Orthodox religion again. It was now one of two equal Eastern churches. Restoring the Orthodox leadership was hard. Most bishops became Uniates, and their Orthodox replacements in 1620 and 1621 were not recognized. This was officially done only during Władysław IV's reign. Władysław faced Cossack rebellions. He stopped decades of efforts to use the Uniate Church to eliminate the Orthodox religion. By then, many Orthodox nobles had become Catholics. Orthodox leadership fell to townspeople and lesser nobles organized into church groups. The new power in the east was the Cossack warrior class. Metropolitan Peter Mogila of Kiev greatly helped rebuild and reform the Orthodox Church. He organized an important academy there.

The Uniate Church, created for the Ruthenian people of the Commonwealth, slowly started using the Polish language in its records. From about 1650, most of the Church's official documents were in Polish, not in the Ruthenian (its Chancery Slavonic version) language.

Early Baroque Culture

The Baroque style became popular in Polish culture from the 1580s. It built on the achievements of the Renaissance and existed alongside it for a while. It lasted until the mid-1700s. At first, Baroque artists and thinkers had a lot of freedom. But soon, the Counter-Reformation set strict rules. It brought back medieval traditions and censored education. The list of prohibited books in Poland started in 1617. By the mid-1600s, the new rules were firmly in place. Sarmatism (a noble ideology) and strong religious beliefs became common. Art often took on an Oriental style. Unlike before, city and noble cultures grew apart.

Around this time, there were about forty Jesuit colleges (high schools) across the Commonwealth. They mostly educated szlachta (nobles), and fewer sons of city dwellers. Jan Zamoyski, Chancellor of the Crown, built the town of Zamość. He founded an academy there in 1594. It only worked as a gymnasium after Zamoyski's death. The first two Vasa kings were known for supporting arts and sciences. After that, science in the Commonwealth generally declined. This happened along with the decline of the city-dwelling class during wartime.

By the mid-1500s, Poland's university, the Academy of Kraków, faced problems. By the early 1600s, it became very strict due to the Counter-reformation. The Jesuits took advantage of internal conflicts. In 1579, they opened a university college in Vilnius. But they failed to take over the Kraków academy. Because of this, many students chose to study abroad. Jan Brożek, a rector of the Kraków University, was a scholar in many fields. He worked on number theory and promoted Copernicus' work. The Church banned him in 1616, and his anti-Jesuit pamphlet was publicly burned. Brożek's colleague, Stanisław Pudłowski, worked on a system of measurements based on physical events.

Michał Sędziwój (Sendivogius Polonus) was a famous European alchemist. He wrote many books in several languages. His Novum Lumen Chymicum (1604) had over fifty editions and translations in the 1600s and 1700s. He was part of Emperor Rudolph II's group of scientists. Some believe he was a pioneer chemist and discovered oxygen, long before Lavoisier. (Sendivogius's works were studied by great scientists, including Isaac Newton.)

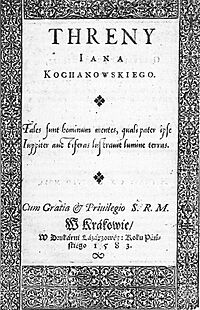

The early Baroque period had many famous poets. Sebastian Grabowiecki wrote metaphysical and mystical religious poems. Another noble poet, Samuel Twardowski, took part in military and historical events. He wrote epic poetry. City poetry was very lively until the mid-1600s. Poets from the common people criticized the social order. The works of John of Kijany had a strong sense of social change. The moralist Sebastian Klonowic wrote a symbolic poem Flis about working on the Vistula river. Szymon Szymonowic in his Pastorals showed the hard lives of serfs without sugarcoating it. Maciej Sarbiewski, a Jesuit, was highly praised across Europe for his Latin poetry.

The best prose of the period was written by Piotr Skarga, a preacher and speaker. In his Sejm Sermons, Skarga strongly criticized the nobility and the state. He supported a system with a strong monarchy. Writing memoirs became very popular in the 1600s. Peregrination to the Holy Land by Mikołaj Radziwiłł and Beginning and Progress of the Muscovy War by Stanisław Żółkiewski (a great Polish military commander) are well-known examples.

Theater was a perfect art form for the Baroque period. Shows were often put on for religious events and to teach morals. They often used folk styles. School theaters became common in both Protestant and Catholic high schools. King Władysław IV set up a permanent court theater with an orchestra at the Royal Castle in Warsaw in 1637. The actors, mostly Italians, performed Italian opera and ballet.

Music, both religious and non-religious, kept developing during the Baroque period. High-quality church pipe organs were built from the 1600s. A beautiful one is still in Leżajsk. Sigismund III supported a famous group of sixty musicians. Adam Jarzębski and Marcin Mielczewski were chief composers for Sigismund III and Władysław IV. Jan Aleksander Gorczyn, a royal secretary, published a popular music guide for beginners in 1647.

Martin Kober, a court painter from Wrocław, worked for Stephen Báthory and Sigismund III. He painted many famous royal portraits.

Between 1580 and 1600, Jan Zamoyski hired the Venetian architect Bernardo Morando to build the city of Zamość. The town and its defenses were designed to follow Renaissance and Mannerism art styles.

Mannerism is a term for the period when late Renaissance and early Baroque art existed together. In Poland, this was from the late 1500s to the early 1600s. Polish art was still influenced by Italian centers, especially Rome, and also by art from the Netherlands. It blended imported and local styles to become a unique Polish form of Baroque.

Baroque art grew largely with the support of the Catholic Church. The Church used art to spread religious influence. It spent a lot of money on this. Architecture was the most important art form. At first, it was simple. Later, it became more detailed and lavish in its facades and interiors.

From the 1580s, many churches were built like the Church of the Gesù in Rome. Gothic and other older churches were given Baroque additions. These included sculptures, wall paintings, and other decorations. You can still see this in many Polish churches today. The Royal Castle in Warsaw, the main home of the kings after 1596, was enlarged and rebuilt around 1611. The Ujazdów Castle (1620s) of the Polish kings was more influential in its design. Many Baroque noble homes followed its style.

Baroque sculpture was usually used as decoration for buildings and tombstones. A famous exception is the Sigismund's Column of Sigismund III Vasa (1644) in front of Warsaw's Royal Castle.

Realistic religious paintings, sometimes whole series of works, served to teach lessons. Mythological themes were banned. But collections of Western paintings were popular. Sigismund III brought Tommaso Dolabella from Venice. He was a very productive painter. He spent the rest of his life in Kraków and started a school of Polish painters who followed his style. Gdańsk (Danzig) was also a center for graphic arts. Painters Herman Han and Bartholomäus Strobel worked there. So did Willem Hondius and Jeremias Falck, who were engravers. Compared to the previous century, more people took part in cultural activities. But the Catholic Counter-Reformation led to less diversity. Terrible wars in the mid-century greatly weakened the Commonwealth's cultural growth and influence.

Parliament and Local Assemblies

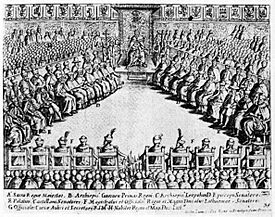

After the Union of Lublin, the Senate of the Commonwealth's general sejm grew. It included high Lithuanian officials. The power of the lay and church lords, who served for life in the Senate, became stronger. The middle szlachta (nobility) had fewer representatives in the upper chamber. The king could also call the Senate to meet separately as his royal council, apart from the Sejm's formal meetings. The nobility's attempts to limit the Senate's role were not successful. After the union and the addition of representatives from the Grand Duchy and Royal Prussia (which joined the Crown more fully in 1569), there were about 170 regional representatives in the lower chamber (called the Sejm) and 140 senators.

Sejm representatives doing legislative work usually could not act as they wished. Regional noble assemblies, called sejmiks, met before the general sejm sessions. There, the local nobility gave their representatives detailed instructions. These instructions told them how to act and protect the local area's interests. Another sejmik was called after the Sejm ended. At that time, the representatives would report to their local group on what had been achieved.

Sejmiks became an important part of the Commonwealth's parliamentary life. They added to the role of the general sejm. Sometimes, they put the Sejm's general rules into practice in detail. Or they made laws when the Sejm was not meeting. Sometimes, they even talked directly with the king.

There was little representation for city dwellers, and none for peasants. Jewish communities sent representatives to their own council, the Va'ad, or Council of Four Lands. The narrow social base of the Commonwealth's parliament system was bad for its future and the future of the Polish–Lithuanian state.

From 1573, a "normal" general sejm was supposed to meet every two years for six weeks. A king could call an "extraordinary" sejm for two weeks if needed. An extraordinary sejm could be made longer if the parliament members agreed. After the Union, the Republic's Sejm met in Warsaw, which was more central. But Kraków remained the place for coronation sejms. Around 1600, the royal court also permanently moved from Kraków to Warsaw.

The order of sejm meetings was set in the 1600s. The lower chamber did most of the work preparing laws. The last few days were spent working with the Senate and the king. This is when the final versions were agreed upon and decisions made. The finished law needed the agreement of all three parts of the government: the Sejm, the Senate, and the king. The lower chamber's rule of needing everyone to agree was not strictly enforced in the first half of the 1600s.

The general sejm was the highest body of shared state power. The Sejm's supreme court, led by the king, decided the most serious legal cases. In the second half of the 1600s, for many reasons, including the misuse of the unanimity rule (liberum veto), the sejm's effectiveness declined. The sejmiks increasingly filled this gap. In practice, most of the government's work was done there.

Noble Rule and First Royal Election

The system of noble democracy became stronger during the first interregnum. This was after the death of Sigismund II Augustus. He wanted to make his personal power stronger after the Union of Lublin, not just follow the nobility's wishes. There was no agreement on how and when to elect his successor. This conflict strengthened the Senate-magnate group. After the king's death in 1572, the nobility formed local confederations (kapturs) to protect their common interests. These acted as local governments, keeping order and providing a basic court system. The magnates managed to get their candidate, the primate Jakub Uchański, chosen as the interrex or regent until a new king was sworn in. The Senate took over election preparations. The idea of all nobles participating (instead of just the Sejm electing) seemed right to most noble groups at the time. But in reality, during this first election and later ones, the magnates controlled and directed the nobles, especially the poorer ones.

During the interregnum, the nobility prepared rules and limits for the future king. These were safeguards to make sure the new king, who would be a foreigner, followed the Commonwealth's political system. They also ensured he respected the nobles' privileges. Since Henry of Valois was the first to sign these rules, they became known as the Henrician Articles. The articles also stated that a wolna elekcja (free election) was the only way for any future king to take office. This prevented any chance of a hereditary monarchy. The Henrician Articles summarized the Polish nobility's rights, including religious freedom. They also added more limits on the elected king. As if that wasn't enough, Henry also signed the pacta conventa. Through this, he accepted more specific duties. The newly crowned Henry soon tried to free himself from these limits. But the outcome of this power struggle was never decided. One year after the election, in June 1574, Henry secretly left for France after learning of his brother's death.

Stephen Báthory's Rule

In 1575, the nobility started a new election. The magnates tried to force the election of Emperor Maximilian II. On December 12, Archbishop Uchański even announced his election. But this was stopped by the nobility's party, led by Mikołaj Sienicki and Jan Zamoyski. They chose Stephen Báthory, Prince of Transylvania. Sienicki quickly arranged for Anna Jagiellon, Sigismund Augustus's sister, to be proclaimed queen on December 15. Stefan Batory was added as her husband and king. The nobility's army (pospolite ruszenie) supported this choice. Batory took over Kraków, where the couple was crowned on May 1, 1576.

Stephen Báthory's reign marked the end of the nobility's reform movement. The foreign king was unsure about the Polish parliament system. He did not fully appreciate what the reformers were trying to do. Batory's relationship with Sienicki soon got worse. Other noble leaders became senators or were busy with their own careers. The reformers managed to move the old appellate court system from the king's control to the Crown and Lithuanian Tribunals, run by the nobility, in 1578 in Poland and 1581 in Lithuania. The complicated sejm and sejmiks system, the temporary confederations, and the lack of good ways to enforce laws were not fixed by the reformers. Many thought that the glorious noble rule was perfect.

Jan Zamoyski, one of the most important people of this time, became the king's main advisor and manager. He was very educated, a talented military leader, and a skilled politician. He often presented himself as a champion of his fellow nobles. But like a typical magnate, Zamoyski gathered many offices and royal land grants. This moved him far from the reform ideals he once supported.

The king himself was a great military leader and a wise politician. One famous conflict Batory had with nobles involved the Zborowski brothers. Samuel was executed on Zamoyski's orders. Krzysztof was sentenced to banishment and lost his property by the sejm court. Batory, being Hungarian, was concerned with his home country's affairs, like other foreign rulers of Poland. Batory failed to enforce the Karnkowski's Statutes. Because of this, he could not control foreign trade through Gdańsk (Danzig). This had very negative economic and political effects for the Republic. Working with his chancellor and later hetman Jan Zamoyski, he was largely successful in the Livonian war. At that time, the Commonwealth could increase its military effort. The combined armed forces from several sources could be up to 60,000 men strong for a campaign. King Batory started the creation of piechota wybraniecka, an important peasant infantry military group.

In 1577, Batory allowed George Frederick of Brandenburg to become a guardian for the mentally ill Albert Frederick, Duke of Prussia. This brought the two German states closer, which was bad for the Commonwealth's long-term interests.

War with Russia over Livonia

King Sigismund Augustus' plan to control the Baltic Sea, called Dominium Maris Baltici, led to the Commonwealth joining the Livonian conflict. This was also another part of Lithuania's and Poland's fights with Russia. In 1563, Ivan IV took Polotsk. After the Stettin peace of 1570 (which involved several powers like Sweden and Denmark), the Commonwealth kept control of most of Livonia, including Riga and Pernau. In 1577, Ivan launched a big attack. He took over most of Livonia for himself or his vassal Magnus, Duke of Holstein, except for the coastal areas of Riga and Reval. A successful Polish–Lithuanian counter-attack was possible because Batory got the necessary money from the nobility.

The Polish forces took back Dünaburg and most of central Livonia. The King and Zamoyski then decided to attack Russian territory directly. This was needed to keep Russian supply lines to Livonia open. Polotsk was retaken in 1579, and the Velikiye Łuki fortress fell in 1580. They tried to take Pskov in 1581, but Ivan Petrovich Shuisky defended the city despite a siege that lasted several months. A truce was arranged in Jam Zapolski in 1582 by the papal legate Antonio Possevino. The Russians left all the Livonian castles they had captured. They also gave up the Polotsk area and left Velizh in Lithuanian hands. Swedish forces, who took over Narva and most of Estonia, helped in the victory. The Commonwealth ended up with a continuous Baltic coast from Puck to Pernau.

Sigismund III Vasa's Reign

Several people were considered for the Commonwealth crown after Stephen Báthory died. These included Archduke Maximilian of Austria. Anna Jagiellon suggested and pushed for her nephew Sigismund Vasa to be elected. He was the son of John III, King of Sweden and Catherine Jagellon, and the Swedish heir apparent. The Zamoyski group supported Sigismund. The group led by the Zborowski family wanted Maximilian. Two separate elections happened, leading to a civil war. The Habsburg's army entered Poland and attacked Kraków. But they were pushed back there. Then, while retreating in Silesia, they were crushed by forces led by Jan Zamoyski at the Battle of Byczyna (1588). Maximilian was taken prisoner.

Meanwhile, Sigismund also arrived and was crowned in Kraków. This began his long reign in the Commonwealth (1587–1632) as Zygmunt III Waza. The idea of a personal union with Sweden gave Polish and Lithuanian leaders political and economic hopes. These included good Baltic trade conditions and a united front against Russia's expansion. However, control of Estonia soon became a point of disagreement. Sigismund's very strong Catholic beliefs seemed threatening to the Swedish Protestant leaders. This led to him being removed from the throne in Sweden in 1599.

Sigismund wanted to ally with the Habsburgs. He even thought about giving up the Polish crown to pursue his goals in Sweden. He held secret talks with them and married Archduchess Anna. Zamoyski accused him of breaking his promises. Sigismund III was humiliated during the sejm of 1592. This made him resent the szlachta even more. Sigismund was determined to strengthen the monarchy's power and promote the Catholic Church through the Counter-Reformation. (Piotr Skarga was one of his supporters.) He did not care about the growing violations of the Warsaw Confederation's religious protections or violence against Protestants. The King was opposed by religious minorities.

From 1605–1607, King Sigismund and his supporters had a fruitless conflict with a group of opposing nobles. During the sejm of 1605, the royal court suggested a major reform of the sejm itself. They wanted to use majority rule instead of the traditional practice of everyone agreeing. Jan Zamoyski, in his last public speech, defended the nobles' rights. This set the stage for the misleading speeches that would dominate the Commonwealth's politics for many decades.

For the sejm of 1606, the royal group hoped to use the glorious Battle of Kircholm victory and other successes. They submitted a more complete reform plan. Instead, the sejm focused on prosecuting those who caused religious disturbances against non-Catholics. Advised by Skarga, the King refused to agree to this proposed law.

The noble opposition, suspecting an attack on their freedoms, called for a rokosz, or an armed confederation. Tens of thousands of unhappy nobles, led by the very Catholic Mikołaj Zebrzydowski and the Calvinist Janusz Radziwiłł, gathered in August near Sandomierz. This started the Zebrzydowski Rebellion.

The Sandomierz articles produced by the rebels mostly aimed to put more limits on the king's power. Royal forces under Stanisław Żółkiewski threatened them. The rebels made an agreement with Sigismund. But then they backed out and demanded the King be removed. The civil war that followed was settled at the Battle of Guzów, where the nobility was defeated in 1607. However, the magnate leaders who supported the King made sure Sigismund's position remained weak. They left the power to settle disputes to the Senate. Whatever was left of the reform movement was stopped, along with the nobles who blocked progress. A compromise was reached to solve the authority crisis. But the victorious lords of the council had no effective political system to help the Commonwealth, which was still in its Golden Age (or some prefer Silver Age).

In 1611, John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg was allowed by the Commonwealth sejm to inherit the Duchy of Prussia fief. This happened after the death of Albert Frederick, the last duke of the Prussian Hohenzollern family. The Brandenburg Hohenzollern branch ruled the Duchy from 1618.

The reforms of the execution movement clearly made the Sejm the main and most powerful part of the government. But this situation did not last long. Various destructive trends, like actions by the nobility and kings, slowly weakened the central legislative body. This void was filled in the late 1500s and 1600s by the increasingly active local sejmiks. These provided an easier and more direct way for noble activists to promote their local interests. Sejmiks gained effective control, limiting the Sejm's power. They themselves started dealing with a wider range of state and local issues.

Besides the over 70 sejmiks, which destabilized central authority, the often unpaid army also started forming their own "confederations," or rebellions. Through looting and terror, they tried to get their pay and pursue other, sometimes political, goals.

Some reforms were pursued by more enlightened nobles. They wanted to expand the Sejm's role at the expense of the king and magnate groups. Elected kings also pursued reforms. Sigismund III, in the later part of his rule, worked well with the Sejm. He made sure that between 1616 and 1632, each session produced much-needed laws. Increased efforts in taxation and maintaining the military led to positive outcomes in some armed conflicts during Sigismund's reign.

Cossacks and Rebellions

In the mid-1500s, there were not many Cossacks in the southeastern borderlands of Lithuania and Poland. But the first groups of Cossack light cavalry were already part of the Polish army around that time. During Sigismund III Vasa's reign, the Cossack problem began to be the Commonwealth's main internal challenge of the 1600s.

Conscious and planned settlement of the fertile but undeveloped region was started in the 1580s and 1590s by Ruthenian dukes from Volhynia. Among Poles, only Jan Zamoyski, who went into the Bracław area, was economically active by the late 1500s. In that area and in Kiev, Polish wealth also began to grow, often through marriage with Ruthenian families. In 1630, the large Ukrainian latifundia (huge estates) were controlled by Ruthenian families like the Ostrogski, Zbaraski, and Zasławski. At the start of the great civil war of 1648, Polish settlers made up barely 10% of the middle and petty nobility. For example, in the well-studied Bracław Voivodeship and Kiev Voivodeship. The early Cossack rebellions were social uprisings, not national anti-Polish movements. As class warfare, they were brutally put down by the state. Sometimes, their leaders were taken to Warsaw for execution.

Cossacks were first semi-nomadic, then also settled East Slavic people from the Dnieper River area. They were known for banditry and looting. They were also famous for their fighting skills and quickly formed military groups. Many of them were, or came from, runaway peasants from the eastern and other parts of the Commonwealth or from Russia. Other important groups were townspeople and even nobles who came from the region or moved to Ukraine. Cossacks saw themselves as free and independent. They followed their own elected leaders, who came from the richer parts of their society. There were tens of thousands of Cossacks already in the early 1600s. They often clashed with the neighboring Turks and Tatars. They raided their Black Sea coastal settlements. Such raids, done by people who were subjects of the Polish king, were unacceptable for the Commonwealth's foreign relations. This was because they broke peace or interfered with the state's policy toward the Ottoman Empire.

During this earlier period of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, a separate Ukrainian national identity was forming. This was partly influenced by the Cossack uprisings and their heroes. The legacy of Kievan Rus' was recognized, as was the heritage of the East Slavic Ruthenian language. Cossacks felt they were members of the "Ruthenian Orthodox nation." (The Uniate Church was almost gone in the Dnieper region by 1633.) But they also saw themselves as members of the (Polish) "Republic-Fatherland." They dealt with sejms and kings as its subjects. Cossacks and the Ruthenian nobility, who had recently been subjects of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, were not formally connected to the Tsardom of Russia.

Besides the leaders of the uprisings, important Ukrainian figures of the period included Dmytro Vyshnevetsky, Samuel Zborowski, Konstanty Wasyl Ostrogski, and Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny.

Many Cossacks were hired to fight in wars for the Commonwealth. This status gave them privileges and often helped them move up in society. The Cossacks disliked when their numbers in the army were reduced. Cossack rebellions usually involved huge movements of common people.

The Ottoman Empire demanded that Cossack power be completely destroyed. However, the Commonwealth needed the Cossacks in the southeast. They provided a good defense against Crimean Tatars raids. Another way to calm the Cossack unrest would be to give noble status to many of them. This would bring them into the Commonwealth's power structure, which is what Cossacks wanted. But this solution was rejected by the magnates and szlachta for political, economic, and cultural reasons. This happened when there was still time for reform, before disasters struck. Instead, the Polish–Lithuanian leaders wavered. They sometimes compromised with the Cossacks, allowing a limited number, called the Cossack register (500 in 1582, 8000 in the 1630s), to serve in the army. The rest were to become serfs to help the magnates settle the Dnieper area. Other times, they brutally used military force to try and control them.

Oppressive actions, often led by Poles, including Crown tenants or their Jewish agents, Ruthenian nobles, and even high-ranking Cossack officers, aimed to control and exploit the Cossack territories and population in the Zaporizhia region. This led to a series of Cossack uprisings. The early ones could have warned the noble lawmakers. While Ukraine was developing economically, Cossacks and peasants generally did not benefit.

In 1591, the Kosiński Uprising was led by Krzysztof Kosiński and brutally put down. New fighting happened in 1594, when the Nalyvaiko Uprising spread across large parts of Ukraine and Belarus. Hetman Stanisław Żółkiewski defeated the Cossack units in 1596, and Severyn Nalyvaiko was executed. A temporary peace followed in the early 1600s. The many wars fought by the Commonwealth needed more involvement from registered Cossacks. But the Union of Brest caused new tensions, as the Cossacks became strong supporters and defenders of Eastern Orthodoxy.

The Time of Troubles in Russia led to peasant rebellions, like the one led by Ivan Bolotnikov. This also caused peasant unrest in the Commonwealth and more Cossack uprisings there.

The uprising of Marek Zhmaylo in 1625 was met by Stanisław Koniecpolski. It ended with Mykhailo Doroshenko signing the Treaty of Kurukove. More fighting soon broke out. It reached its peak in the "Taras night" of 1630, when Cossack rebels under Taras Fedorovych attacked army units and noble estates. The Fedorovych Uprising was controlled by Hetman Koniecpolski. These events led to an increase in the Cossack registry (Treaty of Pereyaslav). But then, Cossack leaders' demands were rejected during the convocation sejm of 1632. Cossacks wanted to take part in free elections as members of the Commonwealth. They also wanted religious rights for the "disuniate" Eastern Christians restored. The 1635 sejm instead voted for more restrictions. It also allowed the building of the Dnieper Kodak Fortress. This was to control Cossack territories more effectively. Another round of fighting, the Pavluk Uprising, followed in 1637–1638. It was defeated, and its leader Pavel Mikhnovych was executed. After new anti-Cossack limits and sejm laws making most Cossacks serfs, the Cossacks rose up again in 1638 under Jakiv Ostryanin and Dmytro Hunia. The uprising was cruelly put down. Existing Cossack lands were taken over by the magnates.

The Commonwealth's struggles with the Cossacks were watched by Moscow's Kremlin. From the late 1620s, Moscow began to see Cossacks as a major source of instability for its rival, Poland-Lithuania. Russian efforts to destabilize Poland using Cossacks in the 1630s were not yet successful. Even though Cossack leaders themselves often suggested uniting with the Tsardom to pressure Poland's ruling classes. The borderlands with Russia became a refuge for Cossacks persecuted after their failed uprisings. Russian-registered Cossack regiments, following the Commonwealth's example, were eventually set up there.

The harsh measures brought relative calm for a decade, until 1648. The leaders saw this as a "golden peace." But for the Cossacks and peasants, this period brought the worst oppression. During that time, the private lands of Ukrainian powerful nobles, like the Kalinowski, Daniłowicz, and Wiśniowiecki families, grew rapidly. The folwark–serfdom economy, which was only then being introduced in Ukraine (much later than in other parts of the Polish Crown), caused unprecedented levels of exploitation. The Cossack issue, seen as a weakness of the Commonwealth, increasingly became a matter in international politics.

Władysław IV's Reign

Władysław IV Vasa, son of Sigismund III, ruled the Commonwealth from 1632–1648. He was born and raised in Poland. He was prepared for the throne from a young age. He was popular, educated, and free of his father's religious biases. He seemed like a promising leader. However, Władysław, like his father, wanted to gain the Swedish throne. He tried to strengthen his royal status and power in Poland and Lithuania to achieve this. Władysław ruled with the help of several important magnates. These included Jerzy Ossoliński, Chancellor of the Crown, Hetman Stanisław Koniecpolski, and Jakub Sobieski, a leader of the middle szlachta. Władysław IV could not gain wider support from the nobility. Many of his plans failed because of a lack of support in the increasingly ineffective sejm. Because he tolerated non-Catholics, Władysław was also opposed by the Catholic clergy and the Pope.

Towards the end of his reign, Władysław IV tried to strengthen his position and ensure his son would succeed him. He planned a war against the Ottoman Empire. He prepared for this despite lacking support from the nobility. To achieve this, the King worked on forming an alliance with the Cossacks. He encouraged them to improve their military readiness and planned to use them against the Turks. He went further in cooperating with them than his predecessors. The war never happened. The King had to explain his offensive war plans during the "inquisition" sejm of 1646. Władysław's son, Zygmunt Kazimierz, died in 1647. The King, weakened, resigned, and disappointed, died in 1648.

Seeking Power in Eastern Europe

The late 1500s and early 1600s brought changes that temporarily weakened the Commonwealth's powerful neighbors: the Tsardom of Russia, the Austrian Habsburg monarchy, and the Ottoman Empire. This gave the Polish–Lithuanian state a chance to improve its position. But this depended on its ability to overcome internal problems. These included isolationist and pacifist tendencies among the szlachta (ruling class). Also, there was rivalry between noble leaders and elected kings, who often tried to bypass limits on their power, like the Henrician Articles.

The almost continuous wars of the first three decades of the new century led to the modernization of the Commonwealth's army. But it did not grow much due to money limits. The total military forces available ranged from a few thousand at the Battle of Kircholm to over fifty thousand, plus the pospolite ruszenie (noble levy), mobilized for the Khotyn (Chocim) campaign of 1621. The remarkable development of artillery in the first half of the 1600s led to the 1650 publication in Amsterdam of Artis Magnae Artilleriae pars prima by Kazimierz Siemienowicz. He was also a pioneer in the science of rocketry. The Commonwealth had excellent heavy (hussar) and light (Cossack) cavalry. But the growing numbers of infantry (peasant, mercenary, and Cossack units) and foreign troops meant these parts were also heavily represented. During the reigns of the first two Vasas, a war fleet was developed. It fought successful naval battles (1609 against Sweden). As usual, money problems hurt the military's effectiveness and the treasury's ability to pay soldiers.

Moldavia

Following earlier plans for an anti-Turkish attack, which did not happen because Stefan Batory died, Jan Zamoyski intervened in Moldavia in 1595. With the Commonwealth army's support, Ieremia Movilă became the hospodar (ruler) as the Commonwealth's vassal. Zamoyski's army pushed back a later attack by Ottoman Empire forces at Ţuţora. The next conflict in the area happened in 1600. Zamoyski and Stanisław Żółkiewski acted against Michael the Brave, hospodar of Wallachia and Transylvania. First, Ieremia Movilă, who Michael had removed in Moldavia, was put back in power. Then Michael was defeated in Wallachia at the Battle of Bucov. Ieremia's brother Simion Movilă became the new hospodar there. For a short time, the entire region up to the Danube became dependent on the Commonwealth. Turkey soon regained its influence, in 1601 in Wallachia and in 1606 in Transylvania. Zamoyski's actions, which were the early part of the Moldavian magnate wars, only extended Poland's influence in Moldavia. They also effectively interfered with the Habsburg plans in this part of Europe. Further military involvement on the southern borders became impossible, as forces were needed more urgently in the north.

War with Sweden

Sigismund III's crowning in Sweden in 1594 happened amidst tensions and instability. These were caused by religious disagreements. When Sigismund returned to Poland, his uncle Charles, the regent, led the Swedish opposition against Sigismund. In 1598, Sigismund tried to solve the issue militarily. But his expedition to his home country was defeated at the Battle of Linköping. Sigismund was taken prisoner and had to agree to harsh terms. After he returned to Poland, the Riksdag of the Estates removed him from the Swedish throne in 1599. Charles then led Swedish forces into Estonia. In 1600, Sigismund declared Estonia part of the Commonwealth. This was like declaring war on Sweden. This happened when the Commonwealth was heavily involved in the Moldavia region.

Jürgen von Farensbach, who commanded the Commonwealth forces, was overwhelmed by Charles's much larger army. Charles's quick attack in 1600 led to him taking over most of Livonia up to the Daugava River, except for Riga. Many local people welcomed the Swedes. By this time, they were increasingly unhappy with Polish–Lithuanian rule. In 1601, Krzysztof Radziwiłł won at the Battle of Kokenhausen. But the Swedish advances were only reversed up to (but not including) Reval after Jan Zamoyski brought in a larger force. Much of this army, being unpaid, returned to Poland. The fighting was continued by Jan Karol Chodkiewicz. With a small group of troops left, he defeated the Swedish attack at Paide (Biały Kamień) in 1604.

In 1605, Charles, now Charles IX, the King of Sweden, launched a new attack. But his efforts were stopped by Chodkiewicz's victories at Kircholm and other places. Polish naval forces also had successes. The war continued without a clear winner. In the armistice of 1611, the Commonwealth managed to keep most of the disputed areas. Various internal and foreign problems, including the inability to pay mercenary soldiers and the Union's new involvement in Russia, prevented a complete victory.

Attempts to Control Russia

After the deaths of Ivan IV and his son Feodor in 1598 (the last tsars of the Rurik Dynasty), Russia entered a period of severe family, economic, and social crisis and instability. As Boris Godunov faced resistance from both peasants and the boyar (noble) opposition, in the Commonwealth, ideas of making Russia a subordinate ally quickly emerged. This could be through a union or by putting a ruler dependent on the Polish–Lithuanian leaders in power.

In 1600, Lew Sapieha led a Commonwealth mission to Moscow. He proposed a union with the Russian state, similar to the Polish–Lithuanian Union. Russian boyars would get rights similar to the Commonwealth's nobility. A decision on a single monarch would be delayed until the current king or tsar died. Boris Godunov, who was also negotiating with Charles of Sweden at the time, was not interested in such a close relationship. Only a twenty-year truce was agreed upon in 1602.

To continue their efforts, the magnates used the earlier death of Tsarevich Dmitry (1591) under mysterious circumstances. They also used the appearance of False Dmitriy I, a pretender claiming to be the tsarevich. False Dmitriy gained the cooperation of the Wiśniowiecki family and Jerzy Mniszech, Voivode of Sandomierz. He promised Mniszech vast Russian estates and marriage to his daughter Marina. Dmitriy became a Catholic. Leading an army of adventurers raised in the Commonwealth, with the quiet support of Sigismund III, he entered Russia in 1604. After Boris Godunov died and his son Feodor was murdered, False Dmitriy I became the Tsar of Russia. He remained tsar until he was killed during a popular uprising in 1606. This also ended the Polish presence in Moscow.

Russia remained unstable under the new tsar Vasili Shuysky. A new false Dmitriy appeared. Tsaritsa Marina even "recognized" him as her husband, whom she thought was dead. With a new army, mostly provided by the Commonwealth's magnates, False Dmitriy II approached Moscow. He tried to take the city but failed. Tsar Vasili IV sought help from King Charles IX of Sweden. He agreed to give Sweden some territory. In 1609, the Russo-Swedish alliance against Dmitriy and the Commonwealth managed to remove the threat from Moscow and strengthen Vasili. This alliance and Swedish involvement in Russian affairs led to a direct military intervention by the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. King Sigismund III started and led this, with support from the Roman Curia.

The Polish army began a siege of Smolensk. The Russo-Swedish relief force was defeated in 1610 by Hetman Żółkiewski at the Battle of Klushino. This victory strengthened the position of the compromise-oriented group of Russian boyars. They were already interested in offering the Moscow throne to Władysław Vasa, son of Sigismund III. Fyodor Nikitich Romanov, the Patriarch of Moscow, was one of the boyar leaders. Under agreements negotiated by Żółkiewski, the boyars removed Tsar Vasili. They accepted Władysław in return for peace, no annexation of Russia into the Commonwealth, the Prince's conversion to the Orthodox religion, and privileges for Russian nobility, including exclusive rights to high offices. After the agreement was signed and Władysław declared tsar, Commonwealth forces entered the Kremlin (1610).

Sigismund III later rejected the compromise. He demanded the tsar's throne for himself. This would mean Russia would be completely controlled by Poland. Most of Russian society rejected this. Sigismund's refusal only made the chaos worse. The Swedes proposed their own candidate and took over Veliki Novgorod. This situation, along with the harsh Commonwealth occupation in Moscow and elsewhere, led to a popular Russian anti-Polish uprising in 1611. There was heavy fighting in Moscow and a siege of the Polish garrison in the Kremlin.

Meanwhile, the Commonwealth forces stormed and took Smolensk in 1611 after a long siege. At the Kremlin, the situation for the Poles worsened despite occasional reinforcements. A massive national and religious uprising spread across Russia. Prince Dmitry Pozharsky and Kuzma Minin effectively led the Russians. A new rescue attempt by Hetman Chodkiewicz failed. The Polish and Lithuanian forces at the Kremlin surrendered in 1612, ending their involvement there. Mikhail Romanov, son of Patriarch Filaret (who was imprisoned in Poland after rejecting Sigismund III's demand for the Russian throne), became the new tsar in 1613.

The war effort, weakened by a rebellious group formed by unpaid soldiers, continued. Turkey, threatened by Polish land gains, got involved at the borders. A peace between Russia and Sweden was agreed to in 1617. Fearing the new alliance, the Commonwealth launched one more major expedition. It took over Vyazma and reached the walls of Moscow. This was an attempt to put Władysław Vasa back on the throne. The city would not open its gates, and there wasn't enough military strength to force a takeover.

Despite the disappointment, the Commonwealth took advantage of Russia's weakness during the Times of Trouble. Through territorial gains, it reversed eastern losses from earlier decades. In the Truce of Deulino of 1619, the Rzeczpospolita gained the Smolensk, Chernihiv, and Novhorod-Siverskyi regions.

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth reached its largest size. But the attempted union with Russia could not happen. The differences in systems, cultures, and religions between the two empires were too great. The annexed territories and the brutally fought wars left a legacy of injustice and a desire for revenge among Russian leaders and people. The huge military effort weakened the Commonwealth. The painful results of the Vasa court's adventurous policies and its allied magnates were soon to be felt.

Commonwealth and the Thirty Years' War

In 1613, Sigismund III Vasa made an agreement with Matthias, Holy Roman Emperor. Both sides agreed to cooperate and help each other put down internal rebellions. This agreement kept the Habsburg monarchy neutral regarding the Commonwealth's war with Russia. But it had more serious consequences after the Bohemian Revolt started the Thirty Years' War in 1618.

The events in Bohemia weakened the Habsburgs in Silesia. There were many ethnically Polish people there. Their ties and interests at that time put them on the Protestant side. Many Polish Lutheran churches, with schools and cultural centers, were set up in the heavily Polish areas around Opole and Cieszyn in eastern Silesia. Also in many cities and towns throughout the region, including Breslau (Wrocław) and Grünberg (Zielona Góra). The threat of a strong Habsburg monarchy to Polish Silesians was strongly felt. Some in King Sigismund's circle, including Stanisław Łubieński and Jerzy Zbaraski, reminded him of Poland's historical rights and options in the area. The King, a strong Catholic, was advised by many not to involve the Commonwealth on the Catholic-Habsburg side. In the end, he decided to support them, but unofficially.

The ten thousand-strong Lisowczycy mercenary division, a very effective military force, had just returned from the Moscow campaign. They were a major problem for the szlachta (nobility). So, they were available for another assignment abroad. Sigismund sent them south to help Emperor Ferdinand II. The intervention by Sigismund's court greatly influenced the first phase of the war. It helped save the Habsburg Monarchy at a critical moment.

The Lisowczycy entered northern Hungary (now Slovakia). In 1619, they defeated the Transylvanian forces at the Battle of Humenné. Prince Bethlen Gábor of Transylvania, who had been besieging Vienna with the Czechs, had to rush back to his country. He made peace with Ferdinand. This seriously hurt the Czech rebels, who were crushed during and after the Battle of White Mountain. Afterwards, the Lisowczycy brutally fought to suppress the Emperor's opponents in Glatz (Kłodzko) region and elsewhere in Silesia, in Bohemia, and Germany.

After the Bohemian Revolt failed, the people of Silesia, including the Polish gentry in Upper Silesia, faced harsh punishments and Counter-Reformation activities. Thousands of Silesians were forced to leave, many ending up in Poland. Later during the war, the province was repeatedly destroyed by military campaigns crossing its territory. At one point, a Protestant leader, Piast Duke John Christian of Brieg, asked Władysław IV Vasa to take control over Silesia. King Władysław, though tolerant in religious matters, like his father, did not want to involve the Commonwealth in the Thirty Years' War. He ended up getting the duchies of Opole and Racibórz as fiefs from the Emperor in 1646. These were reclaimed by the Empire twenty years later. The Peace of Westphalia allowed the Habsburgs to do as they pleased in Silesia. The province was already completely ruined by the war. This led to intense persecution of Protestants, including Polish communities in Lower Silesia, who were forced to emigrate or become Germanized.

Conflicts with the Ottoman Empire and Crimean Khanate

Even though the Rzeczpospolita did not formally join the Thirty Years' War, its alliance with the Habsburg monarchy led to new wars with the Ottoman Empire, Sweden, and Russia. This meant the Commonwealth had a significant impact on the course of the Thirty Years' War. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth also had its own reasons for continuing struggles with these powers.

From the 1500s, the Commonwealth suffered many Tatar invasions. In the 1500s, Cossack raids began attacking Black Sea area Turkish settlements and Tatar lands. In response, the Ottoman Empire sent its vassal Tatar forces, based in Crimea or Budjak areas, against the Commonwealth regions of Podolia and Red Ruthenia. The borderland area to the southeast was in a state of almost constant warfare until the 1700s. Some researchers estimate that over 3 million people were captured and enslaved during the time of the Crimean Khanate.

The most intense period of Cossack raids, reaching as far as Sinop in Turkey, was from 1613–1620. The Ukrainian magnates, for their part, continued their traditional involvement in Moldavia. They kept trying to put their relatives (the Movileşti family) on the hospodar's throne (Stefan Potocki in 1607 and 1612, Samuel Korecki and Michał Wiśniowiecki in 1615). Ottoman chief Iskender Pasha destroyed the magnate forces in Moldavia. He forced Stanisław Żółkiewski in 1617 to agree to the Treaty of Busza at Poland's border. In this treaty, the Commonwealth promised not to get involved in matters concerning Wallachia and Transylvania.

Turkish unease about Poland's influence in Russia, the results of the Lisowczycy expedition against Transylvania (an Ottoman fief in 1619), and the burning of Varna by the Cossacks in 1620 caused the Empire under the young Sultan Osman II to declare a war against the Commonwealth. Their goal was to break and conquer the Polish–Lithuanian state.

The actual fighting, which led to the death of Stanisław Żółkiewski, was started by the old Polish hetman. Żółkiewski, with Koniecpolski and a rather small force, entered Moldavia. He hoped for military help from Moldavian Hospodar Gaspar Graziani and the Cossacks. The aid did not arrive. The hetmans faced a larger Turkish and Tatar force led by Iskender Pasha. After the failed Battle of Ţuţora (1620), Żółkiewski was killed, Koniecpolski was captured, and the Commonwealth was left defenseless. But disagreements between the Turkish and Tatar commanders stopped the Ottoman army from immediately following up with an effective attack.

The Sejm met in Warsaw. The royal court was blamed for endangering the country. But high taxes for a sixty thousand-man army were agreed to. The number of registered Cossacks was allowed to reach forty thousand. The Commonwealth forces, led by Jan Karol Chodkiewicz, were helped by Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny and his Cossacks. They rose against the Turks and Tatars and took part in the upcoming campaign. In practice, about 30,000 regular army soldiers and 25,000 Cossacks faced a much larger Ottoman force under Osman II at Khotyn. Fierce Turkish attacks against the fortified Commonwealth positions lasted throughout September 1621 and were pushed back. The Ottoman Empire's exhaustion and depleted forces made it sign the Treaty of Khotyn. This treaty kept the old territorial situation of Sigismund II (the Dniester River as the border between the Commonwealth and Ottoman fighters). This was a good outcome for the Polish side. After Osman II was killed in a coup, his successor Mustafa I ratified the treaty.

In response to more Cossack attacks, Tatar raids continued. In 1623 and 1624, they reached almost as far west as the Vistula, bringing plunder and captives. A more effective defense was organized by the freed Koniecpolski and Stefan Chmielecki. They defeated the Tatars several times between 1624 and 1633. They used the quarter army supported by Cossacks and the general population. More warfare with the Ottomans took place in 1633–1634 and ended with a peace treaty. In 1644, Koniecpolski defeated Tugay Bey's army at Okhmativ. Before his death, he planned an invasion against the Crimean Khanate. King Władysław IV's ideas for a grand international war-crusade against the Ottoman Empire were stopped by the inquisition sejm in 1646. The state's inability to control the actions of the magnates and the Cossacks contributed to the constant instability and danger on the Commonwealth's southeastern borders.

Losses of Baltic Territory and Sea Access

A more serious threat to the Polish–Lithuanian state came from Sweden. The balance of power in the north shifted in Sweden's favor. The Baltic neighbor was led by King Gustavus Adolphus. He was a very capable and aggressive military leader. He greatly improved the Swedish armed forces. He also took advantage of Protestant enthusiasm. The Commonwealth, tired from wars with Russia and the Ottoman Empire and lacking allies, was poorly prepared for this new challenge. Constant diplomatic maneuvering by Sigismund III made the whole situation seem to the szlachta like another part of the King's Swedish family affairs. In reality, Sweden wanted to control the entire Polish-controlled Baltic coast. This would allow them to profit from controlling the Commonwealth's sea trade, threatening its independent existence.

Gustavus Adolphus chose to attack Riga, the Grand Duchy's most important trade center, in late August 1621. This happened just as the Ottoman army was approaching Khotyn, tying up Polish forces there. The city, stormed several times, had to surrender a month later. Moving inland to the south, the Swedes then entered Courland. With Riga, the Commonwealth lost the most important Baltic seaport in the region and an entry to northern Livonia, the Daugava River crossing. The 1622 Truce of Mitawa gave Poland possession of Courland and eastern Livonia. But the Swedes were to take over most of Livonia north of the Daugava. The Lithuanian forces managed to keep Dyneburg, but suffered a heavy defeat at the Battle of Wallhof.

These losses severely affected the trade and customs income of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The Crown lands were also affected. In July 1626, the Swedes took Pillau. They forced Duke George William, Elector of Brandenburg, a vassal of the Commonwealth in the attacked Ducal Prussia, to remain neutral. The Swedish advance resulted in them taking over the Baltic coastline up to Puck. Gdańsk (Danzig), which remained loyal to the Commonwealth, was blockaded by sea.

The Poles were completely surprised by the Swedish invasion. In September, they tried a counter-attack but were defeated by Gustavus Adolphus at the Battle of Gniew. The forces needed serious modernization. The Sejm passed high taxes for defense, but collections were slow. The situation was partly saved by the City of Gdańsk (Danzig). It quickly started building modern fortifications. Hetman Stanisław Koniecpolski also helped. The skilled commander of the eastern borderlands quickly learned about sea affairs and modern European warfare. Koniecpolski pushed for the necessary expansion of the naval fleet and modernization of the army. He became a good match for Gustavus Adolphus's military skills.

Koniecpolski led a military campaign in spring 1627. He tried to keep the Swedish army in the Duchy of Prussia from moving toward Gdańsk (Danzig). He also wanted to block their reinforcements coming from the Holy Roman Empire. Moving quickly, the Hetman recaptured Puck. Then, at the Battle of Czarne (Hammerstein), he destroyed the forces meant for Gustavus. Koniecpolski's forces kept the Swedes themselves near Tczew. This protected access to Gdańsk (Danzig) and stopped Gustavus Adolphus from reaching his main goal. At the Battle of Oliva, Polish ships defeated a Swedish naval squadron.

Gdańsk (Danzig) was saved. But the next year, the strengthened Swedish army in Ducal Prussia took Brodnica. In early 1629, they defeated Polish units at Górzno. Gustavus Adolphus, from his Baltic coast position, laid an economic siege against the Commonwealth. He also ravaged what he had conquered. At this point, allied forces under Albrecht von Wallenstein were brought in to help keep the Swedes in check. Forced by the combined Polish-Austrian action, Gustavus had to withdraw from Kwidzyn to Malbork. In the process, he was defeated and almost captured by Koniecpolski at the Battle of Trzciana.

But besides being militarily exhausted, the Commonwealth was now pressured by several European diplomats to stop fighting. This was to allow Gustavus Adolphus to intervene in the Holy Roman Empire. The Truce of Altmark left Livonia north of the Daugava and all Prussian and Livonian seaports (except for Gdańsk (Danzig), Puck, Königsberg, and Libau) in Swedish hands. The Swedes were also allowed to charge duties on trade through Gdańsk.

Weakened Power

As Władysław IV was taking the Commonwealth crown, Gustavus Adolphus died. Gustavus had been trying to organize an anti-Polish alliance, including Sweden, Russia, Transylvania, and Turkey. The Russians then tried to get back lands lost in the Truce of Deulino.

In the fall of 1632, a well-prepared Russian army took several strongholds on the Lithuanian side of the border. They began a siege of Smolensk. The well-fortified city held out against a general attack and a ten-month encirclement by a huge force led by Mikhail Shein. At that time, a Commonwealth rescue expedition of similar strength arrived. It was under the very effective military command of Władysław IV. After months of fierce fighting, Shein surrendered in February 1634. The Treaty of Polyanovka confirmed the territorial arrangements from Deulino, with small changes favoring the Tsardom. Władysław gave up his claims to the Russian throne in exchange for money.

Having secured the eastern front, the King could focus on getting back Baltic areas lost by his father to Sweden. Władysław IV wanted to take advantage of the Swedish defeat at Nördlingen. He wanted to fight for both the territories and his Swedish family claims. The Poles were suspicious of his plans and war preparations. The King could only proceed with negotiations. His unwillingness to give up the family claim weakened the Commonwealth's position. According to the Treaty of Stuhmsdorf of 1635, the Swedes left Royal Prussia's cities and ports. This meant the Crown's lower Vistula possessions returned. Sweden also stopped collecting customs duties there. Sweden kept most of Livonia. The Rzeczpospolita kept Courland, which handled Lithuania's Baltic trade and entered a period of prosperity.

The Commonwealth's position regarding the Duchy of Prussia kept getting weaker. Power in the Duchy was taken over by the Electors of Brandenburg. Under the electors, the Duchy became more and more linked to Brandenburg. This was bad for the Commonwealth's political interests. Sigismund III left the Duchy's administration to Joachim Frederick, and then John Sigismund. In 1611, John Sigismund gained the right to Hohenzollern succession in the Duchy with the King's and the Sejm's consent. He actually became the Duke of Prussia in 1618, after Albert Frederick died. He was followed by George William and then Frederick William. In 1641, Frederick William paid a Prussian homage to a Polish king for the last time in Warsaw. The Brandenburg dukes would make small concessions to satisfy the Commonwealth's needs and justify granting privileges. But an irreversible shift in relations was happening.

In 1637, Bogislaw XIV, Duke of Pomerania died. He was the last of the Slavic Griffins Dynasty of the Duchy of Pomerania. Sweden gained control of Pomerania. The Commonwealth only managed to get back its fiefs, Bytów Land and Lębork Land. Władysław IV also tried to get Słupsk Land at the peace conference. But it ended up as part of Brandenburg. After the Peace of Westphalia, Brandenburg controlled all of Pomerania next to the Commonwealth's border, extending south to meet Habsburg lands. Parts of Pomerania were populated by the Slavic Kashubians and Slovincians.

The Thirty Years' War period brought mixed results for the Commonwealth, more losses than gains. But the Polish–Lithuanian state kept its status as one of the few great powers in central-eastern Europe. From 1635, the country had a period of peace. During this time, internal arguments and increasingly ineffective legislative processes stopped any major reforms. The Commonwealth was not ready to deal with the serious challenges that appeared in the mid-century.

|

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la República de las Dos Naciones (1569-1648) para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la República de las Dos Naciones (1569-1648) para niños