Estonia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Republic of Estonia

Eesti Vabariik (Estonian)

|

|

|---|---|

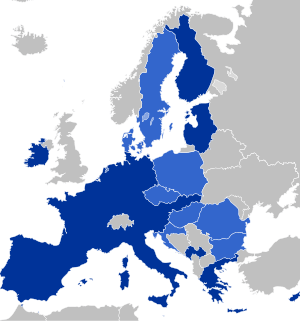

![Location of Estonia (dark green)– on the European continent (green & dark grey)– in the European Union (green) — [Legend]](/images/thumb/a/a2/EU-Estonia.svg/350px-EU-Estonia.svg.png)

Location of Estonia (dark green)

– on the European continent (green & dark grey) |

|

| Capital and largest city

|

Tallinn 59°25′N 24°45′E / 59.417°N 24.750°E |

| Official language | Estonian |

| Ethnic groups (2024) |

|

| Religion

(2021)

|

|

| Demonym(s) | Estonian |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Alar Karis | |

| Kristen Michal | |

| Legislature | Riigikogu |

| Independence

from Russia and Germany

|

|

|

• Declaration of independence

|

23–24 February 1918 |

|

• Joined the League of Nations

|

22 September 1921 |

|

• German and Soviet occupations

|

1940–1991 |

|

• Independence restored

|

20 August 1991 |

| Area | |

|

• Total

|

45,335 km2 (17,504 sq mi) (129thd) |

|

• Water (%)

|

4.6 |

| Population | |

|

• 2024 estimate

|

|

|

• 2021 census

|

1,331,824 |

|

• Density

|

30.3/km2 (78.5/sq mi) (148th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

|

• Total

|

|

|

• Per capita

|

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

|

• Total

|

|

|

• Per capita

|

|

| Gini (2021) | ▲ 30.6 medium |

| HDI (2022) | very high · 31st |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+02:00 (EET) |

|

• Summer (DST)

|

UTC+03:00 (EEST) |

| Calling code | +372 |

| ISO 3166 code | EE |

| Internet TLD | .ee |

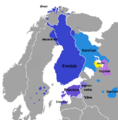

Estonia, also known as the Republic of Estonia, is a small country in the Baltic Region of Northern Europe. Its capital city is Tallinn. Estonia shares borders with Sweden, Finland, Russia, and Latvia. About 1.4 million people live here.

Estonia joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) on March 29, 2004. It also became a member of the European Union on May 1, 2004.

Estonia is located east of the Baltic Sea. It is the northernmost of the Baltic states.

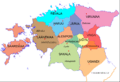

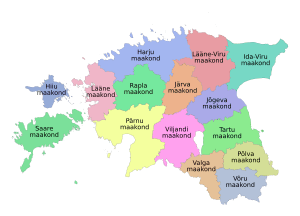

Estonia is divided into 15 areas called counties (maakond). These include Harjumaa, Hiiumaa, Ida-Virumaa, Jõgevamaa, Järvamaa, Läänemaa, Lääne-Virumaa, Põlvamaa, Pärnumaa, Raplamaa, Saaremaa, Tartumaa, Valgamaa, Viljandimaa, and Võrumaa.

Estonia is a very green country. Almost half of its land is covered with forests. It also has over 1,400 lakes and 1,500 islands.

Contents

Estonia's History: From Ancient Times to Today

Early Settlements and the Viking Age

People first settled in Estonia about 11,000 to 13,000 years ago. This was after the ice from the last Ice Age melted. The oldest known settlement is the Pulli settlement, located by the Pärnu River. It is about 11,000 years old.

During the Mesolithic period, people lived in small groups near water. They hunted, gathered, and fished. Around 4900 BC, people started using pottery. Later, around 3200 BC, new ways of life appeared, like early farming and raising animals.

The Bronze Age began around 1800 BC. This is when the first hill forts were built. By 500 BC, during the Iron Age, people lived in single farm settlements. Many bronze items show that people traded with tribes from Scandinavia and Germany.

The middle Iron Age was a time of more wars. Estonian people fought against threats from different directions. Some old stories from Scandinavia tell of Estonians defeating and killing the Swedish king Ingvar. Estonians also fought against Russian groups expanding westward. Around the 11th century, Estonian Vikings from the island of Saaremaa (called Oeselians) became known for their sea raids. In 1187, Estonians even attacked Sigtuna, a major city in Sweden.

In early AD centuries, Estonia started to have local governments. There were parishes (kihelkond) and counties (maakond). A parish was led by elders and had a hill fort. By the 13th century, Estonia had eight main counties and six smaller ones. These counties were independent and only worked together when facing outside threats.

Not much is known about early Estonian religious practices. Some old writings mention Tharapita as a main god for the Oeselians. People believed in shamans, and sacred groves, especially oak groves, were used for worship.

Danish Rule and the Middle Ages

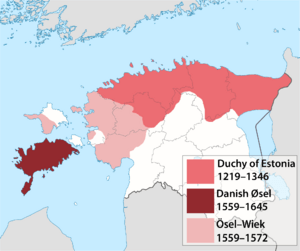

In 1199, Pope Innocent III called for a crusade to Livonia. Fighting reached Estonia in 1206. The Danish king Valdemar II tried to invade Saaremaa but failed. German knights, called the Livonian Brothers of the Sword, began fighting Estonians in 1208. Both sides raided each other's lands for years. A key Estonian leader was Lembitu, but in 1217, Estonians lost a big battle and Lembitu was killed. In 1219, Valdemar II landed in Estonia and began taking over Northern Estonia. The next year, Sweden tried to invade Western Estonia but was stopped by the Oeselians. In 1223, a large uprising pushed out the Germans and Danes from most of Estonia. However, the crusaders soon returned, and in 1227, Saaremaa was the last county to surrender.

After the crusade, the area of modern-day Estonia and Latvia was called Terra Mariana, or later, Livonia. Northern Estonia became the Danish Duchy of Estonia. The rest was divided among the Sword Brothers and church leaders. In 1236, the Sword Brothers joined the Teutonic Order. Over the next decades, there were several uprisings against foreign rulers, especially on Saaremaa. In 1343, a major rebellion called the Saint George's Night Uprising started. It covered all of Northern Estonia and Saaremaa. The Teutonic Order stopped the rebellion in 1345. The next year, the Danish king sold his lands in Estonia to the Order. This rebellion led to the Baltic German minority gaining more power. They remained the ruling group in cities and the countryside for centuries.

During the crusade, Tallinn (then called Reval) was founded as the capital of Danish Estonia. In 1248, Reval became a full town. It adopted the Lübeck law, which set rules for towns. The Hanseatic League controlled trade in the Baltic Sea. Four major Estonian towns became members: Reval, Tartu (Dorpat), Pärnu (Pernau), and Viljandi (Fellin). Reval was a trade link between Velikiy Novgorod and Western Hanseatic cities. Dorpat did the same with Pskov. Many guilds were formed, but few allowed native Estonians to join. These rich cities often challenged other rulers of Livonia.

The Protestant Reformation began in Europe in 1517. It soon spread to Livonia. Towns were the first to accept Protestantism in the 1520s. By the 1530s, most nobles had adopted Lutheranism for themselves and their peasants. Church services began to be held in local languages, including Estonian.

In the 16th century, powerful kingdoms like Russia, Sweden, and Poland–Lithuania grew stronger. This was a big threat to Livonia, which was divided and weakened by internal conflicts.

Swedish Rule in Estonia

In 1558, the Russian czar Ivan the Terrible invaded Livonia. This started the Livonian War. The Livonian Order was badly defeated in 1560. This made Livonian groups seek help from other countries. Most of Livonia accepted Polish-Lithuanian rule. Tallinn and the nobles of Northern Estonia promised loyalty to the Swedish king. The Bishop of Ösel-Wiek sold his lands to the Danish king. Russian forces took over most of Livonia. But in the late 1570s, Polish-Lithuanian and Swedish armies began their own attacks. The war ended in 1583 with Russia's defeat. As a result, Northern Estonia became the Swedish Duchy of Estonia. Southern Estonia became Polish-Lithuanian. Saaremaa stayed under Danish control.

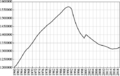

In 1600, the Polish-Swedish War began, causing more damage. This long war ended in 1629. Sweden gained Swedish Livonia, which included Southern Estonia and Northern Latvia. Danish Saaremaa was given to Sweden in 1645. These wars cut Estonia's population in half. It went from about 250,000 people in the mid-16th century to 115,000 in the 1630s.

Even under Swedish rule, serfdom continued. But new laws improved peasants' rights to use and inherit land. This time is remembered as the "Good Old Swedish Time." Swedish king Gustaf II Adolf started schools (gymnasiums) in Tallinn and Dorpat. The one in Dorpat became the University of Tartu in 1632. Printing presses were also set up. In the 1680s, basic education for Estonians began. This was thanks to Bengt Gottfried Forselius, who also improved written Estonian. Estonia's population grew quickly for about 60-70 years. Then, the Great Famine of 1695–97 killed about 70,000–75,000 people. This was about 20% of the population.

National Awakening and Russian Empire Rule

In 1700, the Great Northern War started. By 1710, the Russian Empire had taken over all of Estonia. The war again greatly reduced Estonia's population. By 1712, it was estimated at 150,000–170,000 people. Russian rule gave back all political and land rights to the Baltic Germans. Estonian peasants' rights were at their lowest. Serfdom completely controlled farming during the 18th century. Serfdom was officially ended in 1816–1819. But at first, this did not change much. Major improvements for peasants began with reforms in the mid-19th century.

After serfdom ended and education became available, an Estonian nationalist movement grew. It started with Estonian language literature, theater, and music. This led to the creation of a strong Estonian national identity. By the 18th century, Estonians began calling themselves eestlane, along with the older maarahvas.

The Bible was translated into Estonian in 1739. The number of books published in Estonian grew a lot. By the end of the century, more than half of adult peasants could read. The first educated Estonians who identified as Estonians appeared in the 1820s. These included Friedrich Robert Faehlmann, Kristjan Jaak Peterson, and Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald. The ruling class remained mostly German in language and culture. Garlieb Merkel, a Baltic German who liked Estonians, was the first to treat Estonians as equals. He inspired the Estonian national movement. However, by the mid-19th century, Estonian leaders like Carl Robert Jakobson, Jakob Hurt, and Johann Voldemar Jannsen wanted more political power. They looked to the Finns as a successful example.

Important achievements included the national epic, Kalevipoeg, published in 1862. The first national song festival was held in 1869. In the 1890s, Russia tried to make Estonians more Russian. In response, Estonian nationalism became more political. Intellectuals first asked for more self-rule, then for full independence from the Russian Empire.

Gaining Independence

After the October Revolution in Russia in 1917, and German victories, the Salvation Committee of the Maapäev declared Estonia independent. This happened in Pärnu on February 23 and in Tallinn on February 24, 1918.

German troops then occupied the country. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed, where Russia gave up all claims to Estonia. The Germans left in November 1918. This created a power gap, and Russian Bolshevik troops moved into Estonia. This led to the Estonian War of Independence, which lasted 14 months.

Estonia won the war against Soviet Russia and German volunteer groups. The Tartu Peace Treaty was signed on February 2, 1920. Many countries then recognized the Republic of Estonia.

Estonia was independent for 22 years. It started as a parliamentary democracy. But the parliament (Riigikogu) was closed in 1934 due to political problems from the global economic crisis. Then, Konstantin Päts ruled by decree. He became president in 1938, when parliamentary elections started again.

World War II and Occupations

The future of Estonia in World War II was decided by the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact in August 1939. This pact was a secret agreement between Germany and the Soviet Union. About 25% of Estonia's population died during the war and occupations.

Soviet Occupation

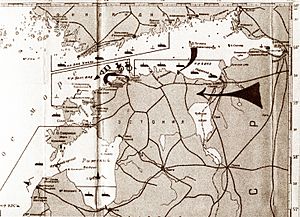

In August 1939, Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler agreed to divide Eastern Europe. This was part of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.

On September 24, 1939, Soviet warships appeared near Estonian ports. Soviet planes flew over Tallinn. The Estonian government had to let the USSR build military bases. They also had to allow 25,000 Soviet troops in Estonia for "mutual defense." On June 12, 1940, the Soviet Baltic Fleet was ordered to block Estonia completely.

On June 14, 1940, the Soviet military blockade of Estonia began. Two Soviet bombers shot down a Finnish passenger plane. On June 16, the Soviet Union invaded Estonia. The Red Army left their bases in Estonia on June 17. The next day, about 90,000 more troops entered the country. Estonia's government gave up on June 17, 1940, to avoid fighting. The Soviet occupation of Estonia was complete by June 21.

Most of the Estonian Defence Forces gave up as ordered by their government. They believed fighting was pointless. The Red Army then disarmed them.

On August 6, 1940, Estonia became part of the Soviet Union. It was called the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic. The Estonian constitution required a public vote to join another country. This rule was ignored. Instead, people elected in the previous month's elections voted to join the Soviet Union. Those who did not vote were punished. The Soviets also carried out mass deportations on June 14, 1941. Many Estonian leaders and thinkers were killed or sent to far-off parts of the USSR. Thousands of ordinary people were also affected.

When Germany attacked the Soviet Union, about 34,000 young Estonian men were forced to join the Red Army. Fewer than 30% of them survived the war. Political prisoners who could not be moved were killed by Soviet police.

Many countries, including the UK and US, did not accept the Soviet takeover of Estonia. They continued to recognize Estonian diplomats. These diplomats worked for their old government until Estonia became independent again.

The official Soviet and current Russian view is that Estonians joined the Soviet Union willingly. Anti-communist fighters from 1944–1976 are called "bandits" or "Nazis" by Russia. However, this view is not accepted by other countries.

German Occupation

Germany invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. German troops crossed Estonia's southern border on July 7. The Red Army pulled back by July 12. By the end of July, the Germans continued their advance in Estonia. They worked with Estonian Forest Brothers (local fighters). German troops and Estonian fighters took Narva on August 17 and Tallinn on August 28. After the Soviets left Estonia, German troops disarmed all the local fighter groups.

At first, most Estonians welcomed the Germans. They hoped to be free from Soviet rule and gain independence. But soon, they realized the Nazis were just another occupying power. The Germans used Estonia's resources for their war. During the occupation, Estonia became part of the German province of Ostland. The Germans and their helpers also carried out the Holocaust in Estonia. They set up 22 concentration camps. Thousands of Estonian Jews, Gypsies, other Estonians, and Soviet prisoners of war were killed.

Some Estonians did not want to join the Nazis directly. They joined the Finnish Army (which was allied with the Nazis) to fight the Soviet Union. The Finnish Infantry Regiment 200 was made of Estonian volunteers in Finland. Many Estonians were forced to join the German army (including the Estonian Waffen-SS). Most of them did so only in 1944. This was when the Red Army was about to invade Estonia again. In January 1944, Estonia faced another Soviet invasion. The last legal prime minister of Estonia asked all able-bodied men to join the military. About 38,000 men joined. Several thousand Estonians who had fought for Finland came back to defend Estonia. They hoped that fighting would make Western countries support Estonia's independence.

Soviet Estonia and Return to Independence

Soviet forces took over Estonia again in autumn 1944. This happened after battles in the northeast of the country.

When the Red Army returned, tens of thousands of Estonians left. Many educated people, artists, scientists, and politicians either left with the Germans or fled to Finland or Sweden. From there, they sought safety in other Western countries. On January 12, 1949, the Soviet government ordered the removal of "all kulaks and their families, the families of bandits and nationalists" from the Baltic states. More than 10% of the adult Baltic population was sent to labor camps or deported. Over 20,000 Estonians were forcibly sent to labor camps or Siberia. Almost all remaining farms were taken over by the state.

After World War II, the Soviet Union wanted to make Estonia more like itself. They continued to deport people and encouraged Russians to move to Estonia. Half of those deported died. The other half were not allowed to return until the early 1960s. The war and Soviet rule greatly slowed Estonia's economic growth. This created a big wealth gap compared to nearby Finland and Sweden.

The Soviet state also made Estonia very military-focused. Large parts of the country, especially coastal areas, were closed to everyone except the Soviet military.

The United States, United Kingdom, France, Italy, and most other Western countries saw the Soviet takeover of Estonia as illegal. They kept diplomatic ties with representatives of the independent Republic of Estonia. They never officially recognized the Estonian SSR as part of the Soviet Union. Estonia became independent again as the Soviet Union faced its own problems.

In the 1980s, a movement for Estonian self-rule began. At first, it was about more economic freedom. But as the Soviet Union weakened, it became clear that full independence was needed. Estonia started working towards self-determination.

In 1989, during the "Singing Revolution", over two million people formed a human chain. This chain stretched through Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. It was called the Baltic Way. All three nations had similar experiences and wanted to regain independence. Estonia declared its sovereignty on November 16, 1988. A country-wide vote on restoring independence was held on March 3, 1991. It was approved by 78.4% of voters. On August 20, 1991, Estonia declared full independence during a Soviet military coup attempt in Moscow. Iceland was the first country to recognize Estonia's independence on August 22, 1991. The Soviet Union recognized Estonia's independence on September 6, 1991. The UN accepted Estonia as a member on September 17, 1991. The last Russian army units left Estonia on August 31, 1994.

Estonia joined NATO on March 29, 2004.

After signing a treaty on April 16, 2003, Estonia joined the European Union on May 1, 2004.

Estonia celebrated its 90th anniversary of independence from November 28, 2007, to November 28, 2008.

Estonia's Geography and Climate

Estonia is on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. It is across the Gulf of Finland from Finland. The land is mostly flat, with an average height of only 50 meters (164 feet). The highest point is Suur Munamägi in the southeast, at 318 meters (1,043 feet). Estonia has 3,794 kilometers (2,357 miles) of coastline with many bays and inlets. There are about 2,355 islands and islets, including those in lakes. Two large islands, Saaremaa and Hiiumaa, are separate counties. A group of meteorite craters, with the largest called Kaali, is found on Saaremaa.

Estonia is in the northern part of the temperate climate zone. It has a mix of maritime and continental climates. Estonia has four seasons that are almost equal in length. Average temperatures in July, the warmest month, are 16.3°C (61.3°F) on the islands and 18.1°C (64.6°F) inland. In February, the coldest month, temperatures range from -3.5°C (25.7°F) on the islands to -7.6°C (18.3°F) inland. The average yearly temperature is 5.2°C (41.4°F). The average rainfall is about 535 to 727 mm (21 to 28.6 inches) per year.

Snow usually covers the ground from mid-December to late March. It is deepest in southeastern Estonia. Estonia has over 1,400 lakes. Most are very small. The largest is Lake Peipus, which is 3,555 square kilometers (1,373 square miles). There are many rivers. The longest are Võhandu (162 km or 101 miles), Pärnu (144 km or 89 miles), and Põltsamaa (135 km or 84 miles). Estonia also has many fens and bogs. Forests cover 50% of Estonia. The most common trees are pine, spruce, and birch.

-

About 2,549 square kilometers (984 square miles) of mires cover 5.6% of Estonia.

Estonia's Government and Politics

Estonia is a parliamentary representative democratic republic. This means people elect representatives to make laws. The Prime Minister of Estonia is the head of government. Estonia has a multi-party system. The political system is stable. Power is usually shared between two or three main parties. This is similar to other countries in Northern Europe. Andrus Ansip was Prime Minister from 2005 to 2014, making him Europe's longest-serving Prime Minister at that time.

How the Government Works

The Government of Estonia (Estonian: Vabariigi Valitsus) is the executive branch. It is formed by the Prime Minister of Estonia. The president chooses the Prime Minister, and the parliament approves them. The government carries out laws and policies. It has twelve ministers, including the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister can also appoint up to three "ministers without portfolio." These ministers do not control a specific ministry.

The government, led by the Prime Minister, makes decisions for the country. It guides and coordinates the work of government groups. It is fully responsible for all executive actions.

Estonia has worked to develop an "e-state" and "e-government." This means using technology for government services. Internet voting is used in Estonian elections. The first internet voting was in 2005 for local elections. For the 2007 parliamentary elections, 30,275 people voted online. Voters can still change their electronic vote at a traditional polling place if they want to. In 2009, Estonia was ranked sixth out of 175 countries for press freedom. In the first ever State of World Liberty Index report, Estonia was ranked first.

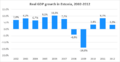

Estonia's Economy

Estonia's economy is closely linked with Sweden and Finland. As a member of the European Union, the World Bank considers Estonia a high-income economy.

In 2010, Estonia had the lowest government debt compared to its GDP among EU countries. This was only 6.7%.

Estonia's economy has a balanced budget and very little public debt. It has a flat-rate income tax and free trade. Its banking sector is competitive. Estonia is also known for its innovative e-services, including mobile services.

Estonia produces about 75% of the electricity it uses. In 2011, about 85% of this came from locally mined oil shale. Other energy sources like wood, peat, and biomass make up about 9% of energy production. Wind energy was about 6% of total use in 2009. Estonia buys petroleum products from Western Europe and Russia. Key parts of Estonia's economy are oil shale energy, telecommunications, textiles, chemicals, banking, food, fishing, timber, shipbuilding, electronics, and transportation. The ice-free port of Muuga, near Tallinn, is a modern port. It has good facilities for moving goods, a large grain storage, and oil tanker unloading. The railroad connects Estonia to the West, Russia, and other Eastern areas.

Natural Resources and Industry

Estonia does not have many natural resources. However, it has large deposits of oil shale and limestone. Forests cover 48% of the land. Estonia also has large amounts of phosphorite, pitchblende, and granite. These are not currently mined much.

Food, construction, and electronics are important industries in Estonia. In 2007, the construction industry employed over 80,000 people. This was about 12% of the country's workers. Other important industries are machinery and chemicals. These are mainly in Ida-Viru County and around Tallinn.

The oil shale mining industry, also in East Estonia, produces about 90% of the country's electricity. Since the 1980s, less pollution has been released into the air. However, the air is still polluted with sulphur dioxide from this industry. In some areas, coastal seawater is polluted, especially near the Sillamäe industrial area.

Estonia relies on its own energy production. In recent years, many companies have invested in renewable energy. Wind power is becoming more important. Currently, wind power produces nearly 60 MW of energy. More projects are being planned, including large ones in the Lake Peipus area and near Hiiumaa.

Estonia has a strong information technology sector. This is partly due to the Tiigrihüpe project in the mid-1990s. Estonia is known as one of the most "wired" and advanced countries in Europe for e-government. A new program, e-residency, offers Estonian services to non-residents.

Skype was created by Estonian developers Ahti Heinla, Priit Kasesalu, and Jaan Tallinn. They also developed Kazaa. Other well-known tech startups include GrabCAD, Fortumo, and TransferWise. Some even say Estonia has the most startups per person in the world.

Trade and Economy Overview

Estonia has had a market economy since the late 1990s. It has one of the highest income levels per person in Eastern Europe. Being close to Scandinavian and Finnish markets, its location between East and West, good costs, and skilled workers have helped Estonia's economy grow. Tallinn has become a financial centre. The Tallinn Stock Exchange is now part of the OMX system. The government has kept strict financial policies. This has led to balanced budgets and low public debt.

Estonia mainly exports machinery, equipment, wood, paper, textiles, food, furniture, metals, and chemicals. It also exports 1.562 billion kilowatt hours of electricity each year. Estonia imports machinery, equipment, chemical products, textiles, food, and transportation equipment. It imports 200 million kilowatt hours of electricity annually.

Estonia's People and Society

| Residents of Estonia by ethnicity (2016) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estonians | 68.8% | |||

| Russians | 25% | |||

| Ukrainians | 1.8% | |||

| Belarusians | 0.9% | |||

| Finns | 0.6% | |||

| Others | 2.9% | |||

Most of Estonia's 15 counties are over 80% ethnic Estonian. Hiiumaa is the most Estonian, with 98.4% of its population being ethnic Estonians. However, in Harju County (which includes Tallinn) and Ida-Viru County, ethnic Estonians make up 60% and 20% of the population, respectively. Russians make up 25.6% of Estonia's total population. They are 36% of the population in Harju county and 70% in Ida-Viru county.

The Estonian Cultural Autonomy law of 1925 was special in Europe. It allowed cultural self-rule for minorities with over 3,000 people who had long ties to Estonia. Before the Soviet occupation, German and Jewish minorities had their own cultural councils. This law was brought back in 1993. Historically, many Coastal Swedes lived along Estonia's northwestern coast and islands.

In recent years, the number of Coastal Swedes has grown again to almost 500 people in 2008. This is due to property reforms in the early 1990s.

Estonian Society Today

Estonian society has changed a lot in the last 20 years. One big change is the difference in income among families. The Gini coefficient (which measures income inequality) has been higher than the European Union average, but it has been falling. In January 2012, the unemployment rate was 7.7%.

Modern Estonia is a country with many different nationalities. According to a 2000 census, 109 languages are spoken. 67.3% of Estonian citizens speak Estonian as their first language. 29.7% speak Russian, and 3% speak other languages. As of July 2, 2010, 84.1% of Estonian residents are Estonian citizens. 8.6% are citizens of other countries, and 7.3% have "undetermined citizenship." Since 1992, about 140,000 people have become Estonian citizens by passing naturalization exams.

Estonia's ethnic makeup is very similar across most areas. In most counties, over 90% of people are ethnic Estonians. This is different from large cities like Tallinn. In Tallinn, Estonians make up 60% of the population. The rest are mostly Russian and other Slavic people who moved to Estonia during the Soviet period.

A 2008 United Nations report called Estonia's citizenship policy "discriminatory." However, surveys show that only 5% of the Russian community in Estonia have thought about moving back to Russia. Estonian Russians have developed their own identity. More than half of them believe that Estonian Russians are different from Russians in Russia. Their outlook on the future is much more positive than in 2000.

Estonia was the first post-Soviet country to legalize civil unions for same-sex couples. The law was approved in October 2014 and became active on January 1, 2016.

A 2013 study found that 53.3% of young ethnic Estonians feel it is important to belong to the Nordic identity group. 52.2% feel the same way about the "Baltic" identity group.

The image that Estonian youths have of their identity is rather similar to that of the Finns as far as the identities of being a citizen of one’s own country, a Fenno-Ugric person, or a Nordic person are concerned, while our identity as a citizen of Europe is common ground between us and Latvians - being stronger here than it is among the young people of Finland and Sweden.

Major Cities in Estonia

Tallinn is the capital and largest city. It is on the northern coast of Estonia, along the Gulf of Finland. Estonia has 33 cities and several town-parish towns. In total, there are 47 linna, which means both "cities" and "towns" in English. More than 70% of the population lives in towns. Here are the 20 largest cities by population:

Largest Cities by Population

- Tallinn = 434,562

- Tartu = 96,974

- Narva = 55,249

- Pärnu = 50,643

- Kohtla-Järve = 33,743

- Viljandi = 17,407

- Maardu = 15,332

- Rakvere = 15,189

- Kuressaare = 13,097

- Haapsalu = 13,077

- Sillamäe = 12,719

- Valga = 12,182

- Võru = 11,859

- Paide = 10,590

- Jõhvi = 10,541

- Keila = 9,910

- Elva = 5,664

- Saue = 5,629

- Põlva = 5,324

- Tapa = 5,316

Religion in Estonia

Before Christianity, Tharapita was a main god for the Oeselians.

Estonia became Christian in the 13th century. This was brought by the Teutonic Knights. During the Protestant Reformation, Protestantism spread. The Lutheran church was officially set up in Estonia in 1686. Before World War II, about 80% of Estonians were Protestant, mostly Lutheran. Many Estonians say they are not very religious. This is because religion in the 19th century was linked to German rule. Historically, there was also a small group of Russian Old-believers near Lake Peipus.

Today, Estonia's constitution protects freedom of religion. It also separates church and state. Estonia is one of the least religious countries in the world. A 2005 survey found that only 16% of Estonians believe in a god. This was the lowest percentage among all countries studied. The historic Lutheran church has about 180,000 members. Other groups report as many as 265,700 Estonian Lutherans. There are also 8,000–9,000 members abroad.

A 2015 study found that 51% of Estonians said they were Christians. 45% said they had no religion. This group includes atheists, agnostics, and those who say "Nothing in Particular." 2% belonged to other faiths. Among Christians, 25% were Eastern Orthodox, 20% Lutherans, 5% other Christians, and 1% Roman Catholic. Among those with no religion, 9% were atheists, 1% agnostics, and 35% "Nothing in Particular."

The largest religious group in Estonia is Lutheranism. It has 160,000 members, mostly ethnic Estonians. Another large group follows Eastern Orthodox Christianity. This is mainly practiced by the Russian minority. The Russian Orthodox Church is the second largest group with 150,000 members.

Languages Spoken in Estonia

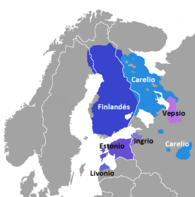

The official language is Estonian. It belongs to the Finnic branch of the Uralic languages. Estonian is very similar to Finnish, spoken in Finland. It is one of the few Languages of Europe that is not from an Indo-European origin. Even though Estonian and Finnish are not related to Swedish, Latvian, or Russian, they have borrowed many words.

Estonian has borrowed almost one-third of its words from Germanic languages. This was mainly from Low Saxon during the time of German rule. About 22–25% of Estonian words come from Low Saxon and High German.

South Estonian (including Võro and Seto) is spoken in southeastern Estonia. It is different from northern Estonian. However, it is usually seen as a dialect or "regional form of the Estonian language," not a separate language.

Russian is still spoken by many Estonians aged 40 to 70. This is because Russian was the unofficial language of the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic from 1944 to 1991. It was taught as a required second language during the Soviet era.

From the 13th to the 20th century, there were Swedish-speaking communities in Estonia. They lived mainly in coastal areas and on islands like Hiiumaa, Vormsi, and Ruhnu. Today, these communities have almost disappeared. The Swedish-speaking minority had representatives in parliament. They could use their native language in debates.

From 1918 to 1940, when Estonia was independent, the small Swedish community was treated well. Towns with a Swedish majority used Swedish as their official language. Swedish-Estonian culture grew. However, most Swedish-speaking people fled to Sweden before the end of World War II. This was before the Soviet army invaded Estonia in 1944. Only a few older speakers remain today.

The influence of Swedish is still clear in the Noarootsi Parish in Lääne County. Many villages there have both Estonian and Swedish names and street signs.

The most common foreign languages learned by Estonian students are English, Russian, German, and French. Other popular languages include Finnish, Spanish, and Swedish.

Estonian Culture

The culture of Estonia combines local traditions, like the Estonian language and the sauna, with wider Nordic and European influences. Because of its history and location, Estonia's culture has been shaped by various Finnic, Baltic, Slavic, and Germanic peoples. It has also been influenced by the former ruling powers, Sweden and Russia.

Music in Estonia

The earliest mention of Estonian singing is from around 1179. It talks about Estonian warriors singing before a battle. Older folk songs are called regilaulud. These songs use a special poetic style shared by all Baltic Finns. This type of singing was common until the 18th century, when rhythmic folk songs became more popular.

Traditional wind instruments, once used by shepherds, are now becoming popular again. Other instruments like the fiddle, zither, concertina, and accordion are used for dance music. The kannel is a native Estonian instrument that is also gaining popularity. A Native Music Preserving Centre opened in 2008 in Viljandi.

The tradition of Estonian Song Festivals (Laulupidu) began in 1869. This was during the Estonian national awakening. Today, it is one of the largest amateur choral events in the world. In 2004, about 100,000 people took part. Since 1928, the the Tallinn Song Festival Grounds (Lauluväljak) has hosted the event every five years in July. The last festival was in July 2014. Youth Song Festivals are also held every four or five years.

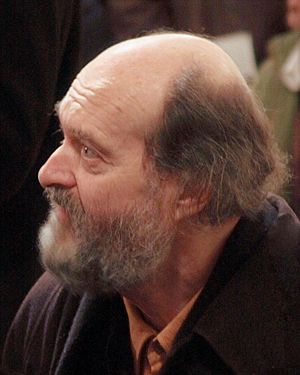

Professional Estonian musicians and composers appeared in the late 19th century. These included Rudolf Tobias, Miina Härma, and Arvo Pärt. Today, the most famous Estonian composers are Arvo Pärt, Eduard Tubin, and Veljo Tormis. In 2014, Arvo Pärt was the world's most performed living composer for the fourth year in a row.

In the 1950s, Estonian baritone Georg Ots became a famous opera singer worldwide.

In popular music, Estonian artist Kerli Kõiv has become popular in Europe and North America. She has provided music for the 2010 Disney film Alice in Wonderland and the TV series Smallville.

Architecture and Cuisine

Estonia's architecture shows its history in Northern Europe. The medieval old town of Tallinn is especially important. It is on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Estonia also has unique, old hill forts from before Christianity. There are many medieval castles and churches that are still in good condition. The countryside also has many old manor houses.

Historically, Estonian food depended on the seasons and simple peasant meals. Today, it includes many international dishes. The most common foods are black bread, pork, potatoes, and dairy products. In summer and spring, Estonians enjoy fresh berries, herbs, and vegetables from the garden. Hunting and fishing were common, but now they are mostly hobbies. Grilling outdoors in summer is also very popular.

In winter, people traditionally eat jams, preserves, and pickles. Gathering and preserving fruits, mushrooms, and vegetables for winter used to be very popular. Today, it is less common because everything can be bought in stores. However, preparing food for winter is still popular in the countryside.

Sports in Estonia

Sport is important in Estonian culture. After gaining independence in 1918, Estonia first competed as a nation at the 1920 Summer Olympics. The National Olympic Committee was set up in 1923. Estonian athletes took part in the Olympics until the Soviet Union took over in 1940. The 1980 Summer Olympics sailing competition was held in Tallinn. After regaining independence in 1991, Estonia has been in all Olympics. Estonia has won most of its medals in athletics, weightlifting, wrestling, and cross-country skiing. Estonia has done very well at the Olympics for a small country. Its best results were 13th in medals at the 1936 Summer Olympics and 12th at the 2006 Winter Olympics.

Famous Estonian athletes include wrestlers Kristjan Palusalu and Johannes Kotkas. Skiers Andrus Veerpalu and Kristina Šmigun-Vähi are also well-known. Other notable athletes are fencer Nikolai Novosjolov, decathlete Erki Nool, tennis players Kaia Kanepi and Anett Kontaveit, and discus throwers Gerd Kanter and Aleksander Tammert.

Kiiking, a new sport, was invented in 1996 by Ado Kosk in Estonia. In Kiiking, a person on a special swing tries to go all the way around (360 degrees).

Paul Keres, an Estonian and Soviet chess grandmaster, was one of the world's best players from the 1930s to the 1960s. He almost got a chance to play for the World Chess Championship five times.

Basketball is also a popular sport. The top Estonian basketball league is called the Korvpalli Meistriliiga. BC Kalev/Cramo are the most recent champions. The University of Tartu team has won the league a record 26 times. Estonian clubs also play in European and regional competitions. The Estonia national basketball team played in the 1936 Summer Olympics and has been in EuroBasket four times.

Kelly Sildaru, an Estonian freestyle skier, won a gold medal in slopestyle at the 2016 Winter X Games. At 13, she became the youngest gold medalist ever at a Winter X Games event. She was also the first Estonian to win a Winter X Games medal. She also won the women's slopestyle at the 2015 and 2016 Winter Dew Tour.

In motorsports, two Estonian drivers have done very well in the World Rally Championship. Markko Märtin won 5 rallies and finished 3rd overall in 2004. Ott Tänak (an active driver) won his first WRC event in 2017. In circuit racing, Marko Asmer was the first Estonian to test a Formula One car in 2003. Sten Pentus and Kevin Korjus have also had success globally.

Internet in Estonia

According to speedtest.net, Estonia has some of the fastest internet download speeds in the world. The average download speed is 27.12 Mbit/s.

Related pages

Images for kids

-

Kuressaare Castle in Saaremaa dates back to the 1380s.

-

"Academia Dorpatensis" (now University of Tartu) was founded in 1632 by King Gustavus as the second university in the kingdom of Sweden. After the king's death it became known as "Academia Gustaviana".

-

According to the August 23, 1939 Nazi-Soviet Pact, the Baltic States (Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) were divided into German and Soviet "spheres of influence" (German copy).

-

The Red Army troops crossing the Soviet-Estonian border in October 1939 after Estonia had been forced to sign the Bases Treaty.

-

The capital Tallinn after bombing by the Soviet Air Force during the war on the Eastern Front in March 1944.

-

The blue-black-white flag of Estonia was raised again on the top of the Pikk Hermann tower on February 24, 1989.

-

The barn swallow (H. r. rustica) is the national bird of Estonia.

-

A Russian Old Believer village with a church on Piirissaar island.

-

Distribution of Finnic languages in Northern Europe.

-

The University of Tartu is one of the oldest universities in Northern Europe and the highest-ranked university in Estonia. According to the Top Universities website, the University of Tartu ranks 285th in the QS Global World Ranking.

-

Building of the Estonian Students' Society in Tartu. It is considered to be the first example of Estonian national architecture. The Treaty of Tartu between Finland and Soviet Russia was signed in the building in 1920.

-

ESTCube-1 is the first Estonian satellite.

-

Jaan Kross is the most translated Estonian writer.

See also

In Spanish: Estonia para niños

In Spanish: Estonia para niños