Currency substitution facts for kids

Imagine a country where people use money from another country to buy things or save their earnings. This is called currency substitution. It means using a foreign currency either alongside or instead of the country's own money.

Currency substitution can be full or partial. Full currency substitution can occur after a major economic crisis, such as in Ecuador, El Salvador, or Zimbabwe. Some small economies, like Liechtenstein, find it easier to use the money of a bigger neighbor, such as the Swiss franc, because it's hard for them to manage their own currency.

Partial currency substitution occurs when residents of a country choose to hold a significant share of their financial assets in a foreign currency. They might do this because they trust the foreign currency more. For example, in the 1990s, Argentina and Peru started using the U.S. dollar more and more.

Contents

What is Currency Substitution?

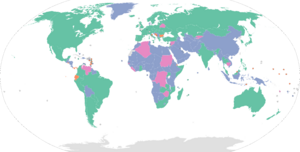

Australian dollar users, including Australia Indian rupee users and pegs, including India New Zealand dollar users, including New Zealand Pound sterling users and pegs, including the United Kingdom Russian ruble users, including Russia and other territories South African rand users (CMA, including South Africa)

Three cases of a country using or pegging the currency of a neighbor

When people talk about "dollarization," it doesn't always mean using the United States dollar. It's just a common term for when a country uses a foreign currency. The most popular foreign currencies used this way are the U.S. dollar and the euro.

Why Do Countries Use Foreign Money?

After big world events like World War I and World War II, countries wanted to make the global economy more stable. They looked for ways to keep their money's value steady. One way was to link their currency to a major, trusted foreign currency.

Some countries choose a "hard peg," which means they are very committed to keeping their money's value fixed to another currency. This can even mean giving up control over their own money, like when countries join a currency union. Other countries use "soft pegs," which are more flexible ways to link their money.

In the late 1990s, many "soft pegs" failed in places like Southeast Asia and Latin America. This made countries think seriously about using foreign currencies.

Before 1999, countries usually adopted foreign currencies for historical or political reasons. For example, Panama started using the U.S. dollar after it became independent.

More recently, countries like Ecuador (in 2000) and El Salvador (in 2001) switched to the U.S. dollar for different reasons. Ecuador did it to fix a big political and financial crisis. People had lost trust in their government and money system. El Salvador, however, made the switch after careful discussions, even though its economy was already stable.

The Eurozone is another example. Many European countries decided to use the euro (€) as their common money in 1999. This is like a full currency substitution, but with countries working together.

Different Ways Countries Use Foreign Money

Unofficial currency substitution is the most common type. This happens when people in a country choose to keep a lot of their savings in foreign money, even if it's not the official money. They might do this if their local money has a history of losing value or to protect themselves from inflation (when prices go up).

Official currency substitution happens when a country completely adopts a foreign currency as its only official money. It stops printing its own money. When a country does this, it also gives up the power to change its money's value compared to other currencies. This has happened a lot in Latin America, the Caribbean, and the Pacific, where countries see the United States Dollar as a very stable currency. For example, Panama officially adopted the U.S. dollar in 1904. This is also called de jure currency substitution.

Sometimes, currency substitution can be semiofficial. This means the foreign currency is used as official money alongside the country's own currency.

How Does Using Foreign Money Affect a Country?

Impact on Trade and Investment

One big benefit of using a strong foreign currency is that it can make trade between countries easier and cheaper. When countries use the same money, they don't have to worry about changing money back and forth, which saves time and costs. This can help a country connect better with the global economy.

Countries that fully adopt a foreign currency might also attract more international investors. This is because investors feel more confident that their money will be safe. It can lead to more investments and economic growth. When there's no risk of a currency crisis, countries might also get lower interest rates on loans.

Impact on Money Management

Official currency substitution can help a country manage its money and economy better. It can lead to more stable prices and lower inflation. By using a foreign currency, a country commits to a stable money policy. It also means the government can't just print more money to pay its debts, which encourages careful spending. Studies show that countries with full currency substitution often have lower inflation rates. It also removes the risk of sudden changes in the exchange rate.

However, there are downsides. A country loses the ability to earn money by printing its own currency (called seigniorage). It also gives up control over its own money policies. For example, the U.S. central bank (the Federal Reserve) makes decisions based on the U.S. economy, not on countries that use the U.S. dollar. This means a country using a foreign currency can't change its money's value to help its economy during tough times.

Impact on Banks

In a country that fully uses a foreign currency, the central bank can't easily help commercial banks by printing money if they run into trouble. This role, called "lender of last resort," is important for keeping banks stable. However, there are other ways to help banks, like through taxes or government loans.

Banks in countries that use foreign currency might face risks. For example, if they take deposits in foreign currency but lend in local currency, they could have a "currency mismatch." But using a foreign currency can also reduce the chance of a big currency crisis that could harm banks. Research suggests that official currency substitution has helped banks in Ecuador and El Salvador become more stable.

What Makes Countries Use Foreign Money?

When Local Money Loses Value

When a country has very high and unexpected inflation (prices rising quickly), people start to lose trust in their local money. They look for other ways to save their wealth, often by buying foreign currency. This is sometimes called a "flight from domestic money."

First, people stop using their local money to save. Then, they might start listing prices for goods and services in foreign currency. If inflation continues for a long time, people might even start using foreign currency for everyday shopping.

Studies show that currency substitution increases when inflation is unstable.

How Rules and Systems Play a Role

How much a country uses foreign money also depends on its rules and systems. If a country has a strong and well-developed financial market, it might offer many ways for people to save in local currency. This can reduce the need for foreign money.

Rules about foreign exchange and capital can also play a part. If a country has strict rules, people might keep their foreign money outside the country or use unofficial markets. But if a country has more foreign currency reserves, it might be able to manage the shift to foreign money better.

Countries Using Other Currencies

Many countries around the world use foreign currencies, either fully or partially. Here are some examples of the main "anchor currencies" they use:

Australian dollar

Kiribati (since 1943; also uses its own coins)

Kiribati (since 1943; also uses its own coins) Nauru (since 1914; also issues non-circulating Nauran collector coins pegged to the Australian dollar)

Nauru (since 1914; also issues non-circulating Nauran collector coins pegged to the Australian dollar) Tuvalu (since 1892; also uses its own coins)

Tuvalu (since 1892; also uses its own coins) Zimbabwe (alongside the United States dollar, South African rand, Botswana pula, Japanese yen, several other currencies and U.S. dollar-denominated bond coins and bond notes of the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) dollar)

Zimbabwe (alongside the United States dollar, South African rand, Botswana pula, Japanese yen, several other currencies and U.S. dollar-denominated bond coins and bond notes of the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) dollar)

Euro

Andorra (formerly French franc and Spanish peseta; issued non-circulating Andorran diner coins; issues its own euro coins). Since 1278, Andorra has used its neighbors' currencies.

Andorra (formerly French franc and Spanish peseta; issued non-circulating Andorran diner coins; issues its own euro coins). Since 1278, Andorra has used its neighbors' currencies. Akrotiri and Dhekelia (Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia); formerly used the Cypriot pound)

Akrotiri and Dhekelia (Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia); formerly used the Cypriot pound) France (used in the overseas territories of the French Southern Territories, Saint Barthélemy, and Saint Pierre and Miquelon. Euro is used in the French overseas and department region of Guadeloupe)

France (used in the overseas territories of the French Southern Territories, Saint Barthélemy, and Saint Pierre and Miquelon. Euro is used in the French overseas and department region of Guadeloupe)

French Polynesia (pegged to the CFP franc at a fixed exchange rate)

French Polynesia (pegged to the CFP franc at a fixed exchange rate) New Caledonia (pegged to the CFP franc at a fixed exchange rate)

New Caledonia (pegged to the CFP franc at a fixed exchange rate) Wallis and Futuna (pegged to the CFP franc at a fixed exchange rate)

Wallis and Futuna (pegged to the CFP franc at a fixed exchange rate)

Kosovo (formerly German mark and Yugoslav dinar)

Kosovo (formerly German mark and Yugoslav dinar) Monaco (formerly French franc from 1865 to 2002 and Monégasque franc; issues its own euro coins)

Monaco (formerly French franc from 1865 to 2002 and Monégasque franc; issues its own euro coins) Montenegro (formerly German mark and Yugoslav dinar)

Montenegro (formerly German mark and Yugoslav dinar) North Korea (alongside the Chinese renminbi, North Korean won, and United States dollar)

North Korea (alongside the Chinese renminbi, North Korean won, and United States dollar) San Marino (formerly Italian lira and Sammarinese lira; issues its own euro coins)

San Marino (formerly Italian lira and Sammarinese lira; issues its own euro coins) Sovereign Military Order of Malta (issues non-circulating Maltese scudo coins at €0.24 = 1 scudo)

Sovereign Military Order of Malta (issues non-circulating Maltese scudo coins at €0.24 = 1 scudo) Vatican City (formerly Italian lira and Vatican lira; issues its own euro coins)

Vatican City (formerly Italian lira and Vatican lira; issues its own euro coins) Zimbabwe (alongside the United States dollar, South African rand, Botswana pula, Japanese yen, several other currencies and U.S. dollar-denominated bond coins and bond notes of the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) dollar)

Zimbabwe (alongside the United States dollar, South African rand, Botswana pula, Japanese yen, several other currencies and U.S. dollar-denominated bond coins and bond notes of the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) dollar)

Indian rupee

Bhutan (alongside the Bhutanese ngultrum, pegged at par with the rupee)

Bhutan (alongside the Bhutanese ngultrum, pegged at par with the rupee) Nepal (alongside the Nepali rupee, pegged at ₹0.625)

Nepal (alongside the Nepali rupee, pegged at ₹0.625) Zimbabwe (alongside the United States dollar, South African rand, Botswana pula, Japanese yen, several other currencies and U.S. dollar-denominated bond coins and bond notes of the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) dollar)

Zimbabwe (alongside the United States dollar, South African rand, Botswana pula, Japanese yen, several other currencies and U.S. dollar-denominated bond coins and bond notes of the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) dollar)

New Zealand dollar

Cook Islands (issues its own coins and some notes.)

Cook Islands (issues its own coins and some notes.) Niue (also issues its own non-circulating commemorative and collector coins minted at the New Zealand Mint, pegged to the New Zealand dollar.)

Niue (also issues its own non-circulating commemorative and collector coins minted at the New Zealand Mint, pegged to the New Zealand dollar.) Pitcairn Islands (also issues its own non-circulating commemorative and collector coins pegged to the New Zealand dollar.)

Pitcairn Islands (also issues its own non-circulating commemorative and collector coins pegged to the New Zealand dollar.) Tokelau (also issues its own non-circulating commemorative and collector coins pegged to the New Zealand dollar.)

Tokelau (also issues its own non-circulating commemorative and collector coins pegged to the New Zealand dollar.)

Pound sterling

British Overseas Territories using the pound, or a local currency pegged to the pound, as their currency:

British Antarctic Territory (issues non-circulating collector coins for the British Antarctic Territory.)

British Antarctic Territory (issues non-circulating collector coins for the British Antarctic Territory.) British Indian Ocean Territory (de jure, U.S. dollar used de facto; also issues non-circulating collector coins for the British Indian Ocean Territory.)

British Indian Ocean Territory (de jure, U.S. dollar used de facto; also issues non-circulating collector coins for the British Indian Ocean Territory.) Falkland Islands (alongside the Falkland Islands pound)

Falkland Islands (alongside the Falkland Islands pound) Gibraltar (alongside the Gibraltar pound)

Gibraltar (alongside the Gibraltar pound) Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha (Tristan da Cunha; alongside the Saint Helena pound in Saint Helena and Ascension; also issues non-circulating collector coins for Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha.)

Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha (Tristan da Cunha; alongside the Saint Helena pound in Saint Helena and Ascension; also issues non-circulating collector coins for Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha.) South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands (alongside the Falkland Islands pound; also issues non-circulating collector coins for South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.)

South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands (alongside the Falkland Islands pound; also issues non-circulating collector coins for South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.)

The Crown Dependencies use a local issue of the pound as their currency:

Guernsey (Guernsey pound)

Guernsey (Guernsey pound)

Alderney (issues non-circulating Alderney pound collector coins, backed by both the Pound sterling and Guernsey pound.)

Alderney (issues non-circulating Alderney pound collector coins, backed by both the Pound sterling and Guernsey pound.)

Isle of Man (Manx pound)

Isle of Man (Manx pound) Jersey (Jersey pound)

Jersey (Jersey pound)

Under plans published in the Sustainable Growth Commission report by the Scottish National Party, an independent Scotland would use the pound as their currency for the first 10 years of independence. This has become known as sterlingisation.

Other countries:

Zimbabwe (alongside the United States dollar, South African rand, Botswana pula, Japanese yen, several other currencies and U.S. dollar-denominated bond coins and bond notes of the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) dollar)

Zimbabwe (alongside the United States dollar, South African rand, Botswana pula, Japanese yen, several other currencies and U.S. dollar-denominated bond coins and bond notes of the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) dollar)

South African rand

Eswatini (alongside the Swazi lilangeni)

Eswatini (alongside the Swazi lilangeni) Lesotho (alongside the Lesotho loti)

Lesotho (alongside the Lesotho loti) Namibia (alongside the Namibian dollar)

Namibia (alongside the Namibian dollar) Zimbabwe (alongside the United States dollar, South African rand, Botswana pula, Japanese yen, several other currencies and U.S. dollar-denominated bond coins and bond notes of the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) dollar)

Zimbabwe (alongside the United States dollar, South African rand, Botswana pula, Japanese yen, several other currencies and U.S. dollar-denominated bond coins and bond notes of the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) dollar)

United States dollar

Used exclusively

British Virgin Islands (also issues non-circulating British Virgin Islands collector coins pegged to the U.S. dollar)

British Virgin Islands (also issues non-circulating British Virgin Islands collector coins pegged to the U.S. dollar) Caribbean Netherlands (since 1 January 2011)

Caribbean Netherlands (since 1 January 2011) Marshall Islands (issued non-circulating collector coins of the Marshall Islands pegged to the U.S. dollar since 1986)

Marshall Islands (issued non-circulating collector coins of the Marshall Islands pegged to the U.S. dollar since 1986) Micronesia (since 1944)

Micronesia (since 1944) Palau (since 1944; issued non-circulating Palauan collector coins pegged to the U.S. dollar since 1992)

Palau (since 1944; issued non-circulating Palauan collector coins pegged to the U.S. dollar since 1992) Turks and Caicos Islands (issued non-circulating Turks and Caicos Islands collector coins denominated in "Crowns" and pegged to the U.S. dollar since 1969)

Turks and Caicos Islands (issued non-circulating Turks and Caicos Islands collector coins denominated in "Crowns" and pegged to the U.S. dollar since 1969)

Used partially

Argentina (the United States dollar is used for major purchases such as buying properties)

Argentina (the United States dollar is used for major purchases such as buying properties) Bahamas (Bahamian dollar pegged at 1:1 but the United States dollar is accepted)

Bahamas (Bahamian dollar pegged at 1:1 but the United States dollar is accepted) Barbados (Barbadian dollar pegged at 2:1 but the United States dollar is accepted)

Barbados (Barbadian dollar pegged at 2:1 but the United States dollar is accepted) Belize (Belizean dollar pegged at 2:1 but the United States dollar is accepted)

Belize (Belizean dollar pegged at 2:1 but the United States dollar is accepted) Bermuda (Bermudian dollar pegged at 1:1 but the United States dollar is accepted)

Bermuda (Bermudian dollar pegged at 1:1 but the United States dollar is accepted) Cambodia (uses the Cambodian riel for many official transactions but most businesses deal exclusively in dollars for all but the cheapest items. Change is often given in a combination of U.S. dollars and Cambodian riel. ATMs yield U.S. dollars rather than Cambodian riel)

Cambodia (uses the Cambodian riel for many official transactions but most businesses deal exclusively in dollars for all but the cheapest items. Change is often given in a combination of U.S. dollars and Cambodian riel. ATMs yield U.S. dollars rather than Cambodian riel) Canada (a modest amount of United States coinage circulates alongside the Canadian dollar and is accepted at par by most retailers, banks and coin redemption machines)

Canada (a modest amount of United States coinage circulates alongside the Canadian dollar and is accepted at par by most retailers, banks and coin redemption machines) Congo-Kinshasa (many institutions accept both the Congolese franc and U.S. dollars)

Congo-Kinshasa (many institutions accept both the Congolese franc and U.S. dollars) Costa Rica (uses alongside the Costa Rican colón)

Costa Rica (uses alongside the Costa Rican colón) Ecuador (since 2000; also uses its own coins)

Ecuador (since 2000; also uses its own coins) El Salvador (uses alongside bitcoin) (see Bitcoin Law and Bitcoin in El Salvador)

El Salvador (uses alongside bitcoin) (see Bitcoin Law and Bitcoin in El Salvador) Haiti (uses the U.S. dollar alongside its domestic currency, the gourde)

Haiti (uses the U.S. dollar alongside its domestic currency, the gourde) Honduras (uses alongside the Honduran lempira)

Honduras (uses alongside the Honduran lempira) Iraq (alongside the Iraqi dinar)

Iraq (alongside the Iraqi dinar) Lebanon (alongside the Lebanese pound)

Lebanon (alongside the Lebanese pound) Liberia (exclusively used the U.S. dollar during the early PRC period, but the National Bank of Liberia began issuing five dollar coins in 1982; United States dollar still in common usage alongside the Liberian dollar)

Liberia (exclusively used the U.S. dollar during the early PRC period, but the National Bank of Liberia began issuing five dollar coins in 1982; United States dollar still in common usage alongside the Liberian dollar) North Korea (alongside the euro, North Korean won, and renminbi)

North Korea (alongside the euro, North Korean won, and renminbi) Panama (since 1904; also uses its own coins)

Panama (since 1904; also uses its own coins) Peru (the main currency is the Peruvian sol)

Peru (the main currency is the Peruvian sol) Somalia (alongside the Somali shilling)

Somalia (alongside the Somali shilling) Somaliland (alongside the Somaliland shilling)

Somaliland (alongside the Somaliland shilling) Timor-Leste (uses its own coins)

Timor-Leste (uses its own coins) Uruguay (the main currency is the Uruguayan peso)

Uruguay (the main currency is the Uruguayan peso) Venezuela (alongside the Venezuelan bolívar; due to hyperinflation, USD is used for purchases such as buying electrical appliances, clothes, spare car parts, and food)

Venezuela (alongside the Venezuelan bolívar; due to hyperinflation, USD is used for purchases such as buying electrical appliances, clothes, spare car parts, and food) Vietnam (alongside the Vietnamese đồng)

Vietnam (alongside the Vietnamese đồng) Zimbabwe (since 2020; alongside the South African rand, British pound, Botswana pula, Japanese yen, several other currencies and U.S. dollar-denominated bond coins and bond notes of the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) dollar)

Zimbabwe (since 2020; alongside the South African rand, British pound, Botswana pula, Japanese yen, several other currencies and U.S. dollar-denominated bond coins and bond notes of the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) dollar)

Others

- Algerian dinar:

Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (de facto independent state, recognized by 45 UN member states, but mostly occupied by Morocco; used in the Sahrawi refugee camps)

Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (de facto independent state, recognized by 45 UN member states, but mostly occupied by Morocco; used in the Sahrawi refugee camps) - Botswana pula:

Zimbabwe (alongside several other currencies and U.S. dollar-denominated bond coins and bond notes of the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) dollar)

Zimbabwe (alongside several other currencies and U.S. dollar-denominated bond coins and bond notes of the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) dollar) - Brunei dollar:

Singapore (alongside the Singapore dollar)

Singapore (alongside the Singapore dollar) - Canadian dollar:

Saint Pierre and Miquelon (alongside the euro)

Saint Pierre and Miquelon (alongside the euro) - Chinese renminbi:

Zimbabwe (alongside several other currencies and U.S. dollar-denominated bond coins and bond notes of the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) dollar)

Zimbabwe (alongside several other currencies and U.S. dollar-denominated bond coins and bond notes of the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) dollar) - Colombian peso:

Venezuela (mainly in western states, alongside U.S. dollar)

Venezuela (mainly in western states, alongside U.S. dollar) - Danish krone:

Faroe Islands (also issues its own coins and some notes)

Faroe Islands (also issues its own coins and some notes) Greenland

Greenland

- Egyptian pound:

Palestine (Palestinian territories)

Palestine (Palestinian territories) - Hong Kong dollar:

Macao (alongside the Macanese pataca, pegged at $1.032)

Macao (alongside the Macanese pataca, pegged at $1.032) - Japanese yen:

Zimbabwe (alongside several other currencies and U.S. dollar-denominated bond coins and bond notes of the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) dollar)

Zimbabwe (alongside several other currencies and U.S. dollar-denominated bond coins and bond notes of the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) dollar) - Jordanian dinar:

West Bank (alongside the New Israeli shekel)

West Bank (alongside the New Israeli shekel) - Mauritanian ouguiya:

Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (de facto independent state, recognized by 45 UN member states, but mostly occupied by Morocco; used in the Sahrawi refugee camps)

Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (de facto independent state, recognized by 45 UN member states, but mostly occupied by Morocco; used in the Sahrawi refugee camps) - Moroccan dirham:

Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (de facto independent state, recognized by 45 UN member states, but mostly occupied by Morocco; used in claimed areas under Moroccan control; issues the non-circulating Sahrawi peseta for collectors)

Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (de facto independent state, recognized by 45 UN member states, but mostly occupied by Morocco; used in claimed areas under Moroccan control; issues the non-circulating Sahrawi peseta for collectors) - New Israeli shekel:

Palestine (Palestinian territories)

Palestine (Palestinian territories) - Russian ruble:

Abkhazia (de facto independent state, but recognized as a part of Georgia internationally; issues non-circulating collector coins (Abkhazian apsar) pegged to the Russian ruble)

Abkhazia (de facto independent state, but recognized as a part of Georgia internationally; issues non-circulating collector coins (Abkhazian apsar) pegged to the Russian ruble) South Ossetia (de facto independent state, but recognized as a part of Georgia internationally; issues non-circulating collector coins (South Ossetian zarin) pegged to the Russian ruble)

South Ossetia (de facto independent state, but recognized as a part of Georgia internationally; issues non-circulating collector coins (South Ossetian zarin) pegged to the Russian ruble)

- Singapore dollar:

Brunei (alongside the Brunei dollar)

Brunei (alongside the Brunei dollar) - Swiss franc:

Germany (uses in the exclave of Büsingen am Hochrhein, alongside the euro)

Germany (uses in the exclave of Büsingen am Hochrhein, alongside the euro) Italy (uses in the enclave of Campione d'Italia, alongside the euro)

Italy (uses in the enclave of Campione d'Italia, alongside the euro) Liechtenstein (also issues non-circulating collector coins)

Liechtenstein (also issues non-circulating collector coins)

- Turkish lira:

Northern Cyprus (de facto independent state, but recognized as a part of Cyprus by all UN member states except Turkey)

Northern Cyprus (de facto independent state, but recognized as a part of Cyprus by all UN member states except Turkey)

See also

- Currency union

- Currency board

- Dedollarisation

- Domestic liability dollarization

- Petrocurrency

- Bitcoin, a cryptocurrency

- World currency

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |