St. Louis County, Missouri facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Saint Louis County

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

Babler State Park, the largest of three state parks in St. Louis County

|

|||

|

|||

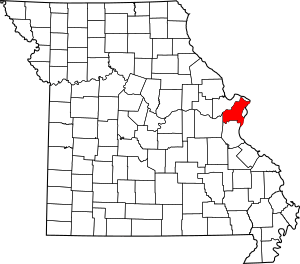

Location within the U.S. state of Missouri

|

|||

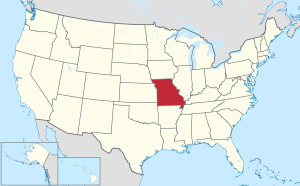

Missouri's location within the U.S. |

|||

| Country | |||

| State | |||

| Founded | October 1, 1812 | ||

| Seat | Clayton | ||

| Largest city | Florissant | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 523 sq mi (1,350 km2) | ||

| • Land | 508 sq mi (1,320 km2) | ||

| • Water | 15 sq mi (40 km2) 2.9% | ||

| Population

(2020)

|

|||

| • Total | 1,004,125 | ||

| • Estimate

(2023)

|

987,059 |

||

| • Density | 1,919.9/sq mi (741.3/km2) | ||

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) | ||

| Congressional districts | 1st, 2nd | ||

St. Louis County is a large area in eastern Missouri. It's bordered by the City of St. Louis and the Mississippi River to the east. The Missouri River is to the north, and the Meramec River is to the south.

In 2020, over 1 million people lived here. This makes it the most populated county in Missouri! Its main government center, called the county seat, is in Clayton. The county is part of the larger St. Louis, MO–IL metropolitan area.

After Great Britain took over French lands east of the Mississippi River, many French settlers moved west. They settled the St. Louis County area. They also founded the city of St. Louis in the late 1700s. The United States gained this land in 1803 through the Louisiana Purchase.

In 1877, people living in the City of St. Louis voted to separate. They wanted to become an independent city. This meant it would have its own government, separate from the county. In the 1960s, more people started moving to the suburbs in St. Louis County. For the first time, the county's population became larger than the city's. Over time, many jobs moved out of the city. The county has continued to grow.

Because of these changes, some leaders have suggested joining the city and county again. They want to create one big government. But in 2019, plans to vote on this idea did not happen.

Contents

History

Early Growth and Schools

After the United States took over the Louisiana territory, new towns could be formed. St. Louis was the first to become a town in 1809. It became a city in 1822. Other towns like St. Ferdinand (now Florissant) and Bridgeton also became official towns.

Towns like Pacific and Kirkwood grew a lot in the 1850s. This was because the Missouri Pacific Railroad was being built. Kirkwood was planned as one of the first suburbs west of the Mississippi River. It became a town in 1865.

Other areas like Chesterfield and Affton were settled later. But they did not become official towns right away.

Public schools started in the city of St. Louis in the 1830s. It took a while for public schools to open in St. Louis County. In 1854, the School District of Maplewood was created. The first school there was a one-room stone building. Another early school district was Rock Hill.

The first school in Florissant opened in 1819. It was run by a Catholic group called the Religious of the Sacred Heart. The teacher, Rose Philippine Duchesne, was a very important educator. The first public school in Florissant opened in 1845.

When St. Louis City and County Separated

In the mid-1800s, some city leaders wanted St. Louis City to be separate from the county. They felt city residents were paying too many taxes. They also felt they didn't have enough say in the county government. In 1844, county voters said no to the idea of separating.

But the arguments continued. City residents felt they were paying double taxes. They paid taxes to both the city and the county for services the city already provided. In 1859, the county government changed. This helped for a little while.

However, the problems came back in the 1860s. City leaders wanted to fix this. They thought about making St. Louis its own independent city. They also thought about joining the city and county into one government. But people in the city and county didn't trust each other. So, separating seemed like the best idea.

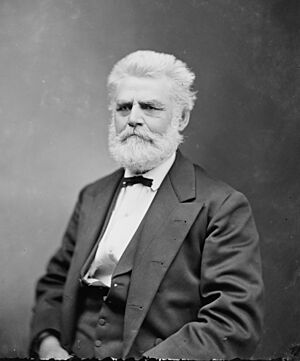

A politician named David H. Armstrong strongly supported the separation. City leaders looked at Baltimore, Maryland, as an example. Baltimore had separated from its county in 1853.

In 1877, the City of St. Louis officially separated from the county. It became an independent city. City residents voted for it, but county residents were mostly against it. At that time, the city had 350,000 people. The county was mostly rural with only 30,000 people. Even though some people tried to stop it in court, the separation became official in March 1877.

More Towns and Schools Grow

After the Civil War, more towns started to form in St. Louis County. Fenton became a town in 1874. Webster Groves became a town in 1896. This happened because residents wanted their own police department.

Other towns that became official before World War I include University City (1906), Maplewood (1908), and Clayton (1913). State law made it easy for new towns to form. If 50% of residents wanted to become a town, it could happen. Many more towns formed quickly after 1935.

After the Civil War, many new school districts opened. They provided basic education. In Eureka, a one-room school opened in 1870. In Kirkwood, private schools started in the 1850s. The first public schools in Kirkwood opened in 1866.

Some private schools later became part of public school districts. For example, the St. Ferdinand School in Florissant joined the Florissant School District in 1871.

After World War II

A new courthouse was built in Clayton in 1945. It is now the County Police headquarters. The old courthouse was replaced in 1971.

After World War II, there were changes in education. The Florissant and Ferguson school districts joined in 1951. Later, in 1975, other school districts were added to help with desegregation.

In 1955, the St. Louis County Police Department was created. It serves the whole county.

By the 1970 census, St. Louis County had more people than the city. The county had 951,353 people, while the city had 622,236. Many jobs moved from the city to the county.

Geography

St. Louis County covers about 523 square miles. Most of this is land (508 square miles), and a small part is water (15 square miles).

People often divide St. Louis County into four parts: Mid, North, West, and South.

- North County is north of Interstate 70.

- West County is west of Interstate 270.

- South County is south of Interstate 44.

- Mid County is in the middle of these highways and the St. Louis city line.

Natural Borders

The Missouri River forms the northern border with St. Charles County. The Meramec River forms most of the southern border with Jefferson County. To the east are the City of St. Louis and the Mississippi River. The western border with Franklin County is where the Meramec and Missouri rivers are closest.

Land Features

The western part of St. Louis County has hills. These are the start of the Ozark Mountains. This area is less developed because of its rough land. Bluffs along the Mississippi River in the south are about 200–300 feet high.

A large flat area is the Chesterfield Valley. It's in the western part of the county along the Missouri River. This area used to be called "Gumbo Flats" because of its rich soil. It was flooded by at least ten feet of water during the Great Flood of 1993. Now, a higher levee protects it.

The Columbia Bottom is a flat area in the northeast. It's where the Mississippi and Missouri rivers meet. This area is a conservation area open to the public. The River des Peres flows through the county. It forms part of the border between St. Louis City and St. Louis County. The highest point in the county is 904 feet high.

Rocks and Minerals

The ground is mostly made of limestone and dolomite. Many areas near the rivers have karst terrain. This means there are many caves, sinkholes, and springs. There are no igneous (volcanic) or metamorphic rocks on the surface.

A special white sandstone, used for making clear glass, is mined in Pacific. Mining clay for bricks was also a big industry here. Coal was found along the Missouri River. Small oil deposits are found in the northern part of the county.

Plants and Animals

Before Europeans arrived, the area had open forests and prairies. Native Americans kept these areas open by burning them. Today, the main trees are oak, maple, and hickory. Smaller trees like eastern redbud and flowering dogwood are also common. Areas near rivers have many American sycamore trees.

Most of the county's timber was cut down by the 1920s. Since then, large parks and undeveloped areas have grown thick forests. Many homes in the county have large native shade trees. In autumn, the trees change color beautifully. St. Louis County has many different native plant species.

Large mammals include growing numbers of whitetail deer and coyotes. These animals are now often seen in urban areas. Small animals like Eastern gray squirrels, cottontail rabbits, opossums, beavers, raccoons, and skunks are common.

Many large birds live here, such as wild turkeys, Canada geese, and mallard ducks. You can also see raptors like turkey vultures and red-tailed hawks. Bald eagles can be seen near the Mississippi River in winter. The county is on the Mississippi Flyway, a path for migrating birds.

Frogs are common in spring, especially after a lot of rain. You might hear American toads and "spring peepers" near ponds. Sometimes there are many cicadas or ladybugs. Mosquitos and houseflies are common insects. Many homes have window screens to keep them out.

Weather and Climate

| Weather chart for St. Louis County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

66

4

-8

|

75

7

-4

|

85

17

4

|

204

24

10

|

108

26

15

|

128

37

20

|

47

31

22

|

113

31

20

|

97

29

17

|

90

21

10

|

46

15

4

|

81

5

-5

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| temperatures in °C precipitation totals in mm |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Imperial conversion

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

St. Louis County has four clear seasons. It gets cold Canadian air and warm, humid air from the Gulf of Mexico.

Spring is the wettest season. It can bring strong storms, including tornadoes. Summers are hot and humid. The heat index can feel like over 100°F. Fall is mild with less humidity. The first snow flurries usually appear in late November. Winters are cool to cold. There is often snow, and temperatures are often below freezing. Winter storms can bring heavy freezing rain, ice pellets, and snowfall.

The average yearly temperature is about 56.3°F. The average rainfall is about 36 inches. The hottest temperature ever recorded was 115°F in July 1954. The coldest was -23°F in January 1873.

Winter is the driest season. Spring is the wettest. Dry periods of one or two weeks are common during the growing seasons.

Thunderstorms happen 40 to 50 days a year. Some can be severe with strong winds and large hail. Sometimes, tornadoes can occur. A warm period in late autumn, called Indian summer, is common.

Other Interesting Places

The largest natural lake in the county is Creve Coeur Lake. It used to be a bend in the Missouri River. Now, it's the main feature of a popular county park.

Manchester Road (Route 100) follows an old path heading west from St. Louis. It's one of only two roads that leave the county without crossing any rivers.

The Sinks is an area in the far northern county with many sinkholes.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1820 | 10,049 | — | |

| 1830 | 14,125 | 40.6% | |

| 1840 | 35,979 | 154.7% | |

| 1850 | 104,978 | 191.8% | |

| 1860 | 190,524 | 81.5% | |

| 1870 | 351,189 | 84.3% | |

| 1880 | 31,888 | −90.9% | |

| 1890 | 36,307 | 13.9% | |

| 1900 | 50,040 | 37.8% | |

| 1910 | 82,417 | 64.7% | |

| 1920 | 100,737 | 22.2% | |

| 1930 | 211,593 | 110.0% | |

| 1940 | 274,230 | 29.6% | |

| 1950 | 406,349 | 48.2% | |

| 1960 | 703,532 | 73.1% | |

| 1970 | 951,353 | 35.2% | |

| 1980 | 973,896 | 2.4% | |

| 1990 | 993,529 | 2.0% | |

| 2000 | 1,016,315 | 2.3% | |

| 2010 | 998,954 | −1.7% | |

| 2020 | 1,004,125 | 0.5% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 987,059 | −1.2% | |

| Independent City of St. Louis seceded from the County in 1876. Population of the City of St. Louis in 1880 was 350,518. U.S. Decennial Census 1790–1960 1900–1990 1990–2000 2010–2020 |

|||

In 2020, there were 1,004,125 people living in St. Louis County. There were over 404,000 households. About 31% of these households had children under 18 living with them.

The population density was about 1,966 people per square mile. The average household had 2.47 people. The average family had 3.05 people.

About 25% of the population was under 18 years old. About 14% were 65 years or older. The average age was 38 years.

The median income for a household was $58,532. For a family, it was $72,680. About 6.9% of the population lived below the poverty line.

| Racial composition | 2010 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| White | 70.3% | 63.0% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 68.9% | 62.2% |

| Black or African American | 23.3% | 24.6% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 2.5% | 3.7% |

| Asian | 3.5% | 4.9% |

| Two or More Races | 1.9% | 5.7% |

Economy

In 2009, the biggest job areas in St. Louis County were:

- Education and health (25.2%)

- Trade and transportation (19.6%)

- Professional business services (12.7%)

The county has the highest average income per person in Missouri ($49,727). Nearly one-fourth of all workers in Missouri are employed in St. Louis County. It also has many experts in plant science.

The St. Louis County Economic Council helps with economic development. Some of the largest employers in the county are:

- Boeing (16,000 employees)

- Washington University in St. Louis (13,200 employees)

- SSM Healthcare (12,400 employees)

- Express Scripts (4,500 employees, with more jobs planned)

Parks and Recreation

St. Louis County has more than 40 parks. These include playgrounds and nature areas. The county also runs recreation centers and the National Museum of Transportation.

Besides county parks, there are three Missouri state parks here:

Part of the Big Muddy National Fish and Wildlife Refuge and the Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site are also in the county. Many towns in the county also have their own parks.

| Name | Area (acres) | Region of St. Louis County† |

|---|---|---|

| Bee Tree Park | 199 | South |

| Bella Fontaine Park | 300 | North |

| Bissell House | 9.3 | North |

| Black Forest Park | 4.3 | South |

| Bohrer Park | 16 | South |

| Bon Oak Park | 15 | North |

| Buder Park | 75 | South |

| Castlepoint Park | 11 | North |

| Cliff Cave Park | 560 | South |

| Clydesdale Park | 117 | South |

| Creve Coeur Park | 2,114 | West |

| Ebsworth Park | 10.5 | West |

| Endicott Park | 24 | North |

| Faust Park | 197 | West |

| Endicott Park | 24 | North |

| Fort Bellefontaine Park | 305.6 | North |

| Greensfelder County Park | 1,646 | West |

| Jefferson Barracks Park | 426 | South |

| King Park | 4 | North |

| Kinloch Park | 9 | North |

| Laumeier Sculpture Park | 105 | South |

| Larimore Park | 22 | North |

| Lemay Park | 18.5 | South |

| Lone Elk County Park | 546 | West |

| Love Park | 89 | West |

| Mathilda-Welmering Park | 6 | South |

| McDonnell Park | 133 | North |

| Memorial Park | 2.7 | North |

| Ohlendorf Park | 10 | South |

| Queeny Park | 564 | West |

| Sioux Passage Park | 188 | North |

| Simpson Park | 206 | South |

| Spanish Lake Park | 245 | North |

| Stacy Park | 35 | West |

| St. Vincent Park | 133 | North |

| Suson Park | 98 | South |

| Sylvan Springs Park | 70 | South |

| Tilles Park | 75 | West |

| Unger Park | 140 | South |

| Veterans Memorial Park | 250 | North |

| West Tyson County Park | 670 | West |

| Winter Park | 160 | South |

| † Regions of St. Louis County as defined by the St. Louis County Parks and Recreation Department. | ||

Education

St. Louis County has many schools and colleges. There are 23 public school districts. There are also 20 private high schools. The county has a public library system and several city libraries. Some county students can also attend special schools in the city of St. Louis.

Public Schools

Here are some of the public school districts:

- Affton School District

- Bayless School District

- Brentwood School District

- School District of Clayton

- Ferguson-Florissant School District

- Hancock Place School District

- Hazelwood School District

- Jennings School District

- Kirkwood School District

- Ladue School District

- Lindbergh Schools

- Maplewood Richmond Heights School District

- Mehlville School District

- Meramec Valley R-III School District

- Normandy Schools Collaborative

- Parkway School District

- Pattonville School District

- Ritenour School District

- Riverview Gardens School District

- Rockwood School District

- School District of University City

- Valley Park School District

- Webster Groves School District

The Special School District of St. Louis County (SSD) helps students with different learning needs.

Private Schools

Here are some private high schools:

- Barat Academy

- Chaminade College Preparatory School (All Boys)

- Christian Brothers College High School (All Boys)

- Cor Jesu Academy (All Girls)

- De Smet Jesuit High School (All Boys)

- Incarnate Word Academy (All Girls)

- John Burroughs School

- Lutheran High School North

- Lutheran High School South

- Mary Institute and St. Louis Country Day School

- Nerinx Hall High School (All Girls)

- The Principia

- Saint Louis Priory School (All Boys)

- St. John Vianney High School (All Boys)

- St. Joseph's Academy (All Girls)

- Ursuline Academy (All Girls)

- Villa Duchesne (All Girls)

- Visitation Academy of St. Louis (All Girls)

- Westminster Christian Academy

- Whitfield School

Colleges and Universities

Here are some colleges and universities in the county:

- Concordia Seminary

- Eden Theological Seminary

- Fontbonne University

- Kenrick–Glennon Seminary

- Logan University

- Maryville University

- Missouri Baptist University

- St. Louis Christian College

- Saint Louis University

- St. Louis Community College

- University of Missouri–St. Louis

- Washington University in St. Louis

- Webster University

Libraries

The main library system is the St. Louis County Library. There are also several smaller city libraries.

Transportation

Major Roads

St. Louis County has many important highways and freeways:

|

|

|

Communities

About one-third of the county's population lives in areas that are not part of any city. These are called unincorporated areas. The county government provides services like police and trash collection for these areas.

There are also 87 municipal governments in St. Louis County. These are cities and villages. They vary a lot in size. Some towns are very small, like Champ with only 10 people in 2020. Others are much larger, like Florissant with over 50,000 people.

St. Louis County communities include:

Cities

- Ballwin

- Bella Villa

- Bellefontaine Neighbors

- Berkeley

- Beverly Hills

- Black Jack

- Breckenridge Hills

- Brentwood

- Bridgeton

- Calverton Park

- Charlack

- Chesterfield

- Clarkson Valley

- Clayton (county seat)

- Cool Valley

- Country Club Hills

- Crestwood

- Creve Coeur

- Crystal Lake Park

- Dellwood

- Des Peres

- Edmundson

- Ellisville

- Eureka

- Fenton

- Ferguson

- Flordell Hills

- Florissant

- Frontenac

- Glendale

- Green Park

- Greendale

- Hazelwood

- Huntleigh

- Jennings

- Kinloch

- Kirkwood

- Ladue

- Lakeshire

- Manchester

- Maplewood

- Maryland Heights

- Moline Acres

- Normandy

- Northwoods

- Oakland

- Olivette

- Overland

- Pacific (mostly in Franklin County)

- Pagedale

- Pasadena Hills

- Pine Lawn

- Richmond Heights

- Riverview

- Rock Hill

- Shrewsbury

- St. Ann

- St. John

- Sunset Hills

- Town and Country

- Twin Oaks

- University City

- Valley Park

- Velda City

- Velda Village Hills

- Vinita Park

- Warson Woods

- Webster Groves

- Wellston

- Wildwood

- Winchester

- Woodson Terrace

Villages

- Bellerive Acres

- Bel-Nor

- Bel-Ridge

- Champ

- Country Life Acres

- Grantwood Village

- Hanley Hills

- Hillsdale

- Marlborough

- Norwood Court

- Pasadena Park

- Sycamore Hills

- Uplands Park

- Westwood

- Wilbur Park

Census-Designated Places

These are areas that are not official cities or villages, but are recognized for census purposes:

Townships

Townships are smaller divisions of the county:

- Airport

- Bonhomme

- Chesterfield

- Clayton

- Concord

- Creve Coeur

- Ferguson

- Florissant

- Gravois

- Hadley

- Jefferson

- Lafayette

- Lemay

- Lewis and Clark

- Maryland Heights

- Meramec

- Midland

- Missouri River

- Normandy

- Northwest

- Norwood

- Oakville

- Queeny

- Spanish Lake

- St. Ferdinand

- Tesson Ferry

- University

- Wildhorse

Unincorporated Communities

These are places that are not part of any city or village:

- Ascalon

- Carsonville

- Earth City

- Fort Belle Fontaine

- Glencoe

- Grover

- Mackenzie

- Peerless Park

- Pond

- Sherman

- Times Beach

See also

In Spanish: Condado de San Luis para niños

In Spanish: Condado de San Luis para niños