History of Maine facts for kids

The U.S. state of Maine has a long and interesting history, stretching back thousands of years to its first human settlers. Its journey to becoming a state in 1820 is also a big part of its story. This article will focus on Maine's history from when Europeans first arrived.

The name Maine has a bit of a mystery around it! One idea is that it was named after a French area called Maine. Another thought is that sailors used the term "the main" or "Main Land" to tell the big part of the state apart from its many islands.

Contents

Early History Before Europeans Arrived

The very first people we know lived in Maine, from about 3000 BC to 1000 BC, were called the Red Paint People. They were a group who lived by the sea and were known for their special burials using red ochre (a type of red clay). After them came the Susquehanna culture, who were the first to use pottery in the area.

When Europeans first arrived, the people living in Maine were Algonquian-speaking Wabanaki groups. These included the Abenaki, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot peoples.

Colonial Times

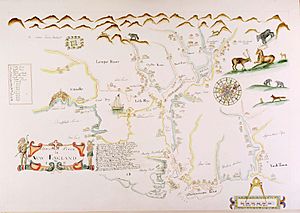

The first Europeans to explore Maine's coast were led by a Portuguese explorer named Estêvão Gomes in 1525, working for Spain. They drew maps of the coast, including the Penobscot River, but they didn't settle there. The first European settlement was on St. Croix Island in 1604 by a French group that included Samuel de Champlain. The French called this area Acadia. French and English settlers fought over central Maine until the 1750s, when the French lost the French and Indian War. The French had strong friendships with the Native American tribes through Catholic missionaries.

English settlers, supported by the Plymouth Company, tried to start a colony in Maine in 1607. This was the Popham Colony at Phippsburg, but they left the next year. A French trading post was set up at what is now Castine in 1613 by Claude de Saint-Étienne de la Tour. This might have been the first lasting European settlement in New England. The Plymouth Colony, started in 1620, also set up a trading post in Penobscot Bay in the 1620s.

The land between the Merrimack River and Kennebec River was first called the Province of Maine in 1622. This name was given in a land agreement to Sir Ferdinando Gorges and John Mason. They split the land along the Piscataqua River in 1629. Mason formed the Province of New Hampshire to the south, and Gorges created New Somersetshire to the north, in what is now southwestern Maine. Today, Somerset County in Maine still uses this old name.

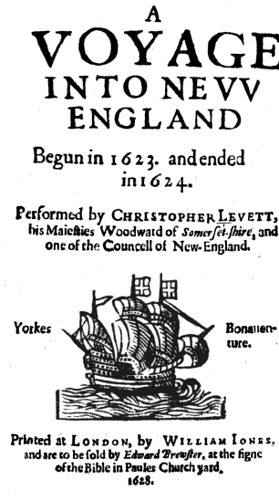

One of the first English attempts to settle the Maine coast was by Christopher Levett. He worked for Gorges and was part of the Plymouth Council for New England. After getting royal permission for about 6,000 acres of land where Portland, Maine is today, Levett built a stone house. He left some men there when he went back to England in 1623 to get more support for his settlement, which he called "York." The local Abenaki people originally called this place Machigonne. Later settlers named it Falmouth, and today it's known as Portland. Levett's settlement, like the Popham Colony, failed, and the men he left behind were never seen again. Levett did sail back to America in 1630 to meet with Massachusetts Bay Colony Governor John Winthrop in Salem, but he died on the way back to England without ever returning to his settlement.

The New Somersetshire colony was small. In 1639, Gorges received another land grant from King Charles I, covering the same area as his 1629 settlement with Mason. Gorges' second try led to more settlements along the southern Maine coast and along the Piscataqua River. A formal government was set up under his relative, Thomas Gorges. A disagreement about land boundaries led to the short-lived Lygonia colony, which covered a large part of Gorges' land. Both Gorges' Province of Maine and Lygonia were taken over by the Massachusetts Bay Colony by 1658. Massachusetts' claim was later overturned in 1676, but Massachusetts took control again by buying the land claims from Gorges' family.

In 1669, the land between the Kennebec and St. Croix rivers was given by King Charles II to his brother James, Duke of York. This land, from the Saint Lawrence River to the Atlantic Ocean, became Cornwall County. It was governed as part of the Duke's own Province of New York. This land, combined with what Massachusetts claimed (which they called York County), covered all of what is now Maine.

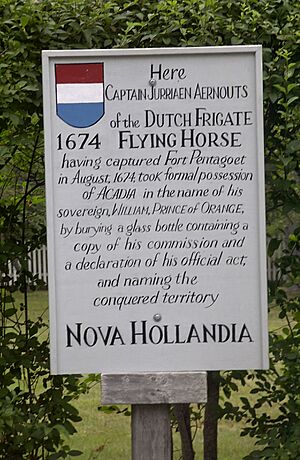

In 1674, the Dutch briefly took over Acadia, renaming the colony New Holland.

In 1686, James, who was now king, created the Dominion of New England. This large area eventually included all English-held lands from Delaware Bay to the St. Croix River. The Dominion fell apart in 1689. In 1692, the land between the Piscataqua and St. Croix rivers became part of the new Province of Massachusetts Bay as Yorkshire. This name still exists today in York County.

Colonial Wars

For the English, the area east of the Kennebec River was known in the 1600s as the Territory of Sagadahock. However, the French considered this area part of Acadia. It was mostly controlled by tribes of the Wabanaki Confederacy, who supported Acadia. The only important European presence was at Fort Pentagouet, a French trading post started in 1613, and missionaries on the Kennebec and Penobscot Rivers. Fort Pentagouet was briefly the capital of Acadia (1670–1674) to protect French claims to the land. There were four wars before the English finally took control of the region in Father Rale's War.

In the first war, King Philip's War, some Wabanaki Confederacy tribes fought and successfully stopped English settlements in their territory. During the next war, King William's War, Baron St. Castin at Fort Pentagouet and French Jesuit missionary Sébastien Rale were very active. Again, the Wabanaki Confederacy successfully fought against the English settlers west of the Kennebec River. In 1696, the main fort in the area, Fort William Henry at Pemaquid (now Bristol, Maine), was attacked by a French force. The area was again on the front lines in Queen Anne's War (1702–1713), with the Northeast Coast Campaign.

The next and final fight over the New England/Acadia border was Father Rale's War. During this war, the Wabanaki Confederacy launched two attacks against British settlers west of the Kennebec (1723, 1724). Rale and many chiefs were killed by a New England force in 1724 at Norridgewock. This led to the end of French claims to Maine.

During King George's War, members of the Wabanaki Confederacy led three attacks against British settlers in Maine (1745, 1746, 1747).

During the last colonial war, the French and Indian War, members of the Wabanaki Confederacy again raided Maine many times from Acadia/Nova Scotia. Acadian soldiers raided the British settlements of Swan's Island, Maine and what are now Friendship, Maine and Thomaston, Maine. Francis Noble wrote about being captured at Swan's Island. During the French and Indian War, on June 9, 1758, Native Americans raided Woolwich, Maine. They killed members of the Preble family and took others prisoner to Quebec. This event was the last conflict on the Kennebec River.

After the French colony of Acadia was defeated, the land from the Penobscot River east came under the control of the Province of Nova Scotia. This area, along with what is now New Brunswick, formed the Nova Scotia County of Sunbury. Its main court was on Campobello Island.

In the late 1700s, some large areas of land in Maine, which was then part of Massachusetts, were sold by lottery. Two areas of 1,000,000 acres, one in southeast Maine and one in the west, were bought by a rich banker from Philadelphia, William Bingham. This land became known as the Bingham Purchase.

American Revolution

Maine was a strong supporter of the American side during the American Revolution. There was less support for the British King here than in most other colonies. Merchants used 52 ships as privateers, which were private ships allowed to attack British supply ships. Machias was especially active in privateering and supporting the American cause. It was the site of an early naval battle where a small British Royal Navy ship was captured. Jonathan Eddy led a failed attempt to capture Fort Cumberland in Nova Scotia in 1776. In 1777, Eddy led the defense of Machias against a Royal Navy attack.

Captain Henry Mowat of the Royal Navy was in charge of operations off the Maine coast for much of the war. He took apart Fort Pownall at the mouth of the Penobscot River and burned Falmouth in 1775 (now Portland, Maine). In Maine's stories, he is often seen as cruel, but historians note that he did his job well according to the rules of that time.

New Ireland

In 1779, the British decided to try and take parts of Maine, especially around Penobscot Bay, and make it a new colony called "New Ireland". This idea was pushed by American Loyalists (people loyal to Britain) who had been forced to leave, like Dr. John Calef and John Nutting, as well as an Englishman named William Knox. The plan was for it to be a permanent home for Loyalists and a base for military actions during the war. However, the plan failed because the British government wasn't very interested, and the Americans were determined to keep all of Maine.

In July 1779, British general Francis McLean captured Castine and built Fort George on the Bagaduce Peninsula on the eastern side of Penobscot Bay. The state of Massachusetts sent the Penobscot Expedition led by Massachusetts general Solomon Lovell and Continental Navy captain Dudley Saltonstall. The Americans failed to remove the British during a 21-day siege and were defeated when British reinforcements arrived. The Royal Navy blocked their escape by sea, so the Americans burned their ships near what is now Bangor and walked home. Maine couldn't stop the British threat, even with a new defense plan and strict rules in some areas. Some of the easternmost towns tried to stay neutral.

After the peace treaty was signed in 1783, the New Ireland plan was given up. In 1784, the British separated New Brunswick from Nova Scotia and made it the Loyalist colony they wanted. It was almost named "New Ireland."

The Treaty of Paris that ended the war was unclear about the border between Maine and the nearby British areas of New Brunswick and Quebec. This confusion would lead to the "Aroostook War" about 50 years later.

War of 1812

During the War of 1812, Maine was affected by the fighting more than most parts of New England. Early in the war, there were some Canadian privateer attacks and British Royal Navy harassment along the coast. In September 1813, a famous battle off Pemaquid between HMS Boxer and USS Enterprise gained international attention. But it wasn't until 1814 that the area was truly invaded. The U.S. Army and the small U.S. Navy could do little to defend Maine. The national government sent few resources to the region, focusing its efforts on the west. The local militia (citizen soldiers) were generally not strong enough for the challenge.

However, in the last months of the war, large groups of militia gathered, which stopped enemy attacks at Wiscasset, Bath, and Portland. British army and navy forces from nearby Nova Scotia captured and occupied the eastern coast from Eastport to Castine. They also plundered the Penobscot River towns of Hampden and Bangor (see Battle of Hampden). Legal trade all along the Maine coast mostly stopped, which was a very serious problem for a place that relied so much on shipping. Instead, illegal smuggling with the British developed, especially at Castine and Eastport. The British gave "New Ireland" back to America in the Treaty of Ghent, and Castine was evacuated, though Eastport remained occupied until 1818. But Maine's weakness to foreign invasion, and its lack of protection from Massachusetts, were important reasons for the push for statehood after the war.

Maine's Constitution and Becoming a State

The Maine Constitution was fully approved by the 210 representatives at the Maine Constitutional Convention in October 1819. It was then approved by the United States Congress on March 4, 1820, as part of the Missouri Compromise. In this agreement, free northern states allowed Missouri to become a slave state in exchange for Maine becoming a free state. This way, the number of northern representatives stayed balanced with the southern pro-slavery influence in the Senate.

Maine officially became a state, separate from Massachusetts, on March 15, 1820. William King became the state's first Governor. William D. Williamson became the first President of the Maine State Senate. When King stepped down as governor in 1821, Williamson automatically took his place, becoming Maine's second governor. However, that same year, he ran for and won a seat in the 17th United States Congress. After Williamson resigned, the Speaker of the Maine House of Representatives, Benjamin Ames, became Maine's third governor for about a month until Daniel Rose took office. Rose served only from January 2 to January 5, 1822, finishing the term between Ames and Albion K. Parris. Parris served as governor until January 3, 1827. So, in less than two years after becoming a state, Maine had five different governors!

The Aroostook War

The border dispute with British North America finally became a big issue in 1839. Maine Governor John Fairfield declared what was almost war on lumberjacks from New Brunswick who were cutting timber in lands Maine claimed. Four groups of the Maine militia gathered in Bangor and marched to the border, but there was no actual fighting. The Aroostook War was a conflict without a formal declaration of war and no bloodshed, and it was settled through talks.

U.S. Secretary of State Daniel Webster secretly paid for a campaign to convince Maine leaders that a compromise was a good idea. Webster used an old map that showed British claims were real. The British had a different old map that showed the American claims were real, so both sides thought the other had a stronger case. The final border between the two countries was set with the Webster–Ashburton Treaty of 1842. This treaty gave Maine most of the disputed area and gave the British a very important connection between their areas of Canada (now Quebec and Ontario) and New Brunswick.

The strong feelings during the Aroostook War showed how important lumbering and logging were becoming to Maine's economy, especially in the central and eastern parts of the state. Bangor grew into a booming lumber town in the 1830s, and it became a possible rival to Portland in terms of population and politics. Bangor was, for a time, the biggest lumber port in the world, and there was a lot of wild land speculation (buying and selling land quickly to make money) that spread up the Penobscot River valley and beyond.

Industrial Growth

Industrial growth in Maine during the 1800s took different forms depending on the area and time. River valleys, especially the Kennebec and Penobscot, became like conveyor belts for making lumber starting in the 1820s-30s. Logging crews went deep into the Maine woods looking for pine (and later spruce) and floated it down to sawmills built near waterfalls. The lumber was then shipped from ports like Bangor, Ellsworth, and Cherryfield all over the world.

Because the lumber industry needed transportation, and because there was a lot of wood and many carpenters along Maine's long coastline, shipbuilding became a very important industry in Maine's coastal towns. Maine's merchant ships were huge compared to the state's population. Ships and crews from places like Bath, Brewer, and Belfast could be found all over the world. The building of very large wooden sailing ships continued in some places into the early 1900s.

Cotton textile mills started moving to Maine from Massachusetts in the 1820s. The main place for cotton textile manufacturing was Lewiston on the Androscoggin River. This was the most northern of the Waltham-Lowell system towns (factory towns built like those in Lowell, Massachusetts). The twin cities of Biddeford and Saco, as well as Augusta, Waterville, and Brunswick, also became important textile manufacturing communities. These mills were built near waterfalls and in farming areas because they first relied on young women from farms who worked for short periods. After the Civil War, these mills attracted many immigrant workers.

Besides fishing, other important industries in the 1800s included granite and slate quarrying (digging out stone), brick-making, and shoe-making.

Starting in the early 1900s, the pulp and paper industry spread into the Maine woods and most river valleys, taking over from the lumbermen. It became so widespread that Ralph Nader famously called Maine a "paper plantation" in the 1960s. Entirely new cities, like Millinocket and Rumford, were built on the upper parts of the large rivers.

Despite all this industrial growth, Maine remained mostly an agricultural state well into the 1900s. Most of its people lived in small, spread-out villages. With short growing seasons, rocky soil, and being far from markets, farming in Maine was never as successful as in other states. The populations of most farming communities reached their highest point in the 1850s and then steadily declined.

Railroads

Railroads changed Maine's landscape, just as they did for most American states. The first railroad in Maine was the Calais Railroad, approved by the state in 1832. It was built to carry lumber from a mill on the Saint Croix River across from Milltown, New Brunswick, two miles to the tidewater at Calais in 1835. In 1849, its name changed to the Calais and Baring Railroad, and the line was extended four more miles to Baring. In 1870, it became part of the St. Croix and Penobscot Railroad.

The state's second railroad was the Bangor & Piscataquis Railroad & Canal Company, approved in 1833. It ran eleven miles from Bangor to Oldtown along the west bank of the Penobscot River and opened in November 1836. In 1854-55, it was extended 1.5 miles across the Penobscot River to Milford, and its name changed to the Bangor, Oldtown & Milford Railroad Company. In 1869, it was taken over by the European and North American Railway.

The third railroad in Maine was the Portland, Saco and Portsmouth Railroad, approved in 1837. This was a very important step for railroads in Maine because it connected Portland to Boston. It did this by linking to the Eastern Railroad at Kittery via a bridge to Portsmouth. This railroad opened on November 21, 1842, and was 51.34 miles long.

Portland especially thrived as the end point of the Grand Trunk Railway from Montreal, essentially becoming Canada's winter port. The Portland Company built early train engines, and the Portland Terminal Company managed shared train switching for the Maine Central Railroad and Boston and Maine Railroad. A railroad reached Bangor in the 1850s and went as far as Aroostook County in the early 1900s, helping potato farming become a major crop.

Some railroads, like the Sandy River and Rangeley Lakes Railroad, Bridgton and Saco River Railroad, Monson Railroad, Kennebec Central Railroad, and Wiscasset, Waterville and Farmington Railway, were built with a very narrow track width of 2 feet (60 cm).

"Ohio Fever", the California Gold Rush, and Moving West from Maine

Even before most of Maine was fully settled, some people started leaving for the West. The first big move was probably in 1816-17. This was caused by the difficulties of the War of 1812, an unusually cold summer, and the chance to settle west of the Appalachian Mountains in Ohio. "Ohio Fever," as the pull of the West was first called, caused some new Maine communities to lose people and slowed the growth of others. However, the overall growth of settlement had mostly returned by the 1820s, when Maine became a state.

As the American frontier kept moving westward, Mainers were especially drawn to the forested states of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. Many brought their logging skills and knowledge there. People who moved from Maine were very noticeable in Minnesota; for example, three mayors of Minneapolis in the 1800s were from Maine.

The California Gold Rush of 1849 and later greatly boosted Maine's lumber and coastal shipbuilding industries. Building lumber needed to be "shipped around the Horn" (around South America) from Maine until a sawmilling industry developed on the West Coast. Maine ships also carried people looking for gold. This meant many Mainers (and parts of Maine culture, like logging and carpentry) were moved to California and the Pacific Northwest. Three mayors of San Francisco in the 1800s, two Governors of California, a Governor of Oregon, and two Governors of Washington were born in Maine.

Civil War

Maine was the first state in the northeast to support the new anti-slavery Republican Party. This was partly due to the influence of strong religious beliefs and partly because Maine was a frontier state, open to the party's "free soil" idea (meaning new territories should be free of slavery). Abraham Lincoln chose Maine's Hannibal Hamlin as his first Vice President.

Maine was so enthusiastic about keeping the Union together during the American Civil War that it sent more soldiers, compared to its population, than any other Union state. It was second only to Massachusetts in the number of its sailors who served in the United States Navy. Joshua Chamberlain and Holman Melcher, along with the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment, played a key role at the Battle of Gettysburg. The 1st Maine Heavy Artillery Regiment lost more men in a single charge (at the Siege of Petersburg) than any other Union regiment in the war.

One lasting effect of the war was the dominance of the Republican Party in state politics for the next 50 years and beyond. State elections happened in September and gave experts a key sign of how voters felt across the North. The phrase "as Maine goes, so goes the nation" was well-known.

In the 50 years from 1861 to 1911 (when Democrats briefly won most state offices), Maine Republicans served as Vice President, Secretary of State, Secretary of the Treasury (twice), President pro tempore of the Senate, Speaker of the House (twice), and Republican Nominee for the Presidency. This close link between Maine's politics and the nation's changed greatly in 1936. Maine became one of only two states to vote for the Republican candidate, Alf Landon, during Franklin D. Roosevelt's huge re-election victory. Maine Republicans are still important in state politics, but since the election of the Polish-American Catholic Democrat Edmund Muskie as governor in the 1950s, Maine has been a balanced two-party state. Important Maine Republicans in recent decades include former Senator William Cohen, and Senators Olympia Snowe and Susan Collins.

Immigrants

Irish

Maine saw a wave of Irish immigration in the mid-1800s. Many came to the state through Canada, and before the potato famine. There was a riot in Bangor between Irish and Yankee (nativist, meaning anti-immigrant) sailors and lumbermen as early as 1834. Several early Catholic churches were burned or damaged in coastal towns, where the Know-Nothing Party (an anti-immigrant political group) briefly grew strong. After the Civil War, Maine's Irish-Catholic population began to become more accepted and move up in society.

French Canadians

In the late 1800s, many French Canadians arrived from Quebec and New Brunswick to work in the textile mill cities like Lewiston and Biddeford. By the mid-1900s, Franco-Americans (people of French-Canadian descent) made up 30% of the state's population. Some immigrants became lumberjacks, but most settled in industrial areas and in communities known as 'Little Canadas.'

French-Canadian immigrant women saw the United States as a place of opportunity. They could create different lives for themselves than what their parents and community expected. By the early 1900s, some French-Canadian women even saw moving to the United States for work as a step into adulthood and a time to discover themselves and become independent. When these women did marry, they had fewer children with longer breaks between children than women in Canada. Some women never married, and stories suggest that being independent and financially stable were important reasons for choosing work over marriage and motherhood. These women kept some traditional ideas from before they moved to keep their 'Canadienne' cultural identity. But they also changed these roles in ways that gave them more independence as wives and mothers.

The Franco-American community in New England tried to keep some of its cultural ways. This idea, like efforts to keep French culture alive in Quebec, was known as la Survivance (the Survival). With the decline of the state's textile industry during the 1950s, the French group experienced a period of moving up in society and blending in. This blending in increased during the 1970s and 1980s as many Catholic organizations changed to English names and children from Catholic schools started going to public schools; some Catholic schools closed in the 1970s. Although some connections to its French-Canadian origins remain, the community was mostly English-speaking by the 1990s, moving almost completely from 'Canadien' to 'American.'

A good example of this blending in was the career of singer and American pop culture icon Rudy Vallée (1901–86). He grew up in Westbrook, Maine. After serving in World War I, he attended the University of Maine, then transferred to Yale, and became a popular music star. He never forgot his Maine roots and kept a home at Kezar Lake.

Other Immigrants

English and Scottish

Many immigrants of English and Scottish background moved from the Maritime Provinces of Canada.

Somalis

In the 2000s, Somalis began moving to Maine from other states. They came because of the area's low crime rate, good schools, and affordable housing.

Mainly living in Lewiston, Somalis have opened community centers to support their community. In 2001, the non-profit group United Somali Women of Maine (USWM) was founded in Lewiston. It aims to help Somali women and girls across the state.

In August 2010, the Lewiston Sun Journal newspaper reported that Somali business owners had helped bring life back to downtown Lewiston by opening many shops in places that used to be empty. Local shopkeepers of French-Canadian descent and the Somali shopkeepers also reported friendly relationships.

Bantus

Because of the civil war in Somalia, the United States government decided to help the Somali Bantu (an ethnic minority group in Somalia) as a priority. They began preparing to resettle about 12,000 Bantu refugees in certain cities across the U.S. Most of the first arrivals in the United States settled in Clarkston, Georgia, a city next to Atlanta. However, they were mostly placed in low-rent, poor inner-city areas. So, many began to look for new places to live in the U.S. After 2005, many Bantus were resettled in Maine by aid organizations. Catholic Charities Maine is the main group that provides services for the Bantus' resettlement.

Maine's Bantu community is served by the Somali Bantu Community Mutual Assistance Association of Lewiston/Auburn Maine (SBCMALA). This group focuses on housing, jobs, reading and education, and health and safety issues.

Population Changes

Largely because of Irish and French-Canadian immigration, 40% of Maine's population was Catholic by 1900. The Catholic Church ran its own school system in the cities, where almost all Catholics lived. These population changes and their social and political effects led to a negative reaction in the 1920s. The Ku Klux Klan formed groups in several Maine towns, showing opposition to these changes.

However, the immigrant population was largely responsible for the steady growth of the Democratic Party. This gave Maine a true two-party system after World War II. The election of Governor Edmund Muskie in 1954 was a major turning point. He was a Catholic Polish American tailor's son from the mill-town of Rumford. The governor from 2003 to 2011, John Baldacci, has Italian American and Arab American family roots from Bangor.

Summer Residents

Maine's natural beauty, cool summers, and closeness to large East Coast cities made it a popular tourist spot as early as the 1850s. Visitors enjoyed local crafts. The most successful effort was creating a picture of Maine as a peaceful, rustic escape from modern city problems. This image, carefully built up for 150 years, brings tourist money to a state that has faced economic challenges. Summer resorts like Bar Harbor, Sorrento, and Islesboro appeared along the coast. Soon, city dwellers were building houses—from huge mansions to small shacks, but all called "cottages"—in what used to be shipbuilding and fishing villages. Maine's seasonal residents changed the economy of the coast and, to some extent, its culture, especially when some started staying all year round.

The Bush family and their home in Kennebunkport are a well-known example of this group. The Rockefeller family were prominent members of the summer community at Bar Harbor. Summer residents who were painters and writers began to shape the state's image through their work.

Modern Maine

By the mid-1900s, the textile industry found it more profitable to set up in the American South. Some Maine cities began to lose their factories as wages rose above those in the South. In 1937, the Lewiston-Auburn Shoe Strike involved 4,000 to 5,000 textile workers on strike in Lewiston and Auburn. It was one of the biggest labor disputes in the state's history. Shipbuilding also stopped in all but a few places, notably Bath and its successful Bath Iron Works. This company became a major builder of naval ships during World War II and afterward. In recent years, however, even Maine's most traditional industries have faced threats. Efforts to conserve forests have reduced logging, and rules on fishing have also put a lot of pressure on coastal areas. The last "heavy industry" in Maine, pulp and paper, began to shrink in the late 1900s, leaving the future of the Maine Woods uncertain.

In response, the state tried to boost retail and service industries, especially those linked to tourism. The label Vacationland was added to license plates in the 1960s. More recent tax breaks have encouraged outlet shopping centers, like the group of stores at Freeport. More and more visitors began to enjoy Maine's vast areas of mostly untouched wilderness, mountains, and long coastline. State and national parks in Maine also became popular spots for middle-class tourism, especially Acadia National Park on Mount Desert Island.

The growth of Portland and areas of southern Maine, and the loss of job opportunities (and people) in the northern and eastern parts of the state, led to discussions in the 1990s about "two Maines," possibly with different interests. Aside from Portland and certain coastal towns, Maine remains the poorest state in the Northeast. By some measures, when you consider its high taxes and living costs, Maine has been the poorest state in the United States since at least the 1970s. The idea that Maine is indeed the poorest state in the US is supported by its very high levels of reliance on welfare over the past half century.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Maine para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Maine para niños

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |