History of Georgia (country) facts for kids

The nation of Georgia (Georgian: საქართველო sakartvelo) was first unified as a kingdom under the Bagrationi dynasty by the King Bagrat III of Georgia in the early 11th century, arising from a number of predecessor states of the ancient kingdoms of Colchis and Iberia. The Kingdom of Georgia flourished during the 10th to 12th centuries under King David IV the Builder and Queen Tamar the Great, and fell to the Mongol invasion by 1243, and after a brief reunion under George V the Brilliant to the Timurid Empire. By 1490, Georgia was fragmented into a number of petty kingdoms and principalities, which throughout the Early Modern period struggled to maintain their autonomy against Ottoman and Iranian (Safavid, Afsharid, and Qajar) domination until Georgia was finally annexed by the Russian Empire in the 19th century. After a brief bid for independence with the Democratic Republic of Georgia of 1918–1921, Georgia was part of the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic from 1922 to 1936, and then formed the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic until the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

The current republic of Georgia has been independent since 1991. The first president Zviad Gamsakhurdia stoked Georgian nationalism and vowed to assert Tbilisi's authority over Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Gamsakhurdia was deposed in a bloody coup d'état within the same year and the country became embroiled in a bitter civil war, which lasted until 1995. Supported by Russia, Abkhazia and South Ossetia achieved de facto independence from Georgia. The Rose Revolution forced Eduard Shevardnadze to resign in 2003. The new government under Mikheil Saakashvili prevented the secession of a third breakaway republic in the Adjara crisis of 2004, but the conflict with Abkhazia and South Ossetia led to the 2008 Russo–Georgian War and tensions with Russia remain unresolved.

The history of Georgia is inextricably linked with the history of the Georgian people.

Contents

- Prehistoric period

- Medieval Georgia and the Georgian Golden Age

- Zenith of development under Queen Tamar

- Nomadic invasions and the gradual decline of Georgia

- Early modern period

- The Russian annexations

- Modern history

- Images for kids

- See also

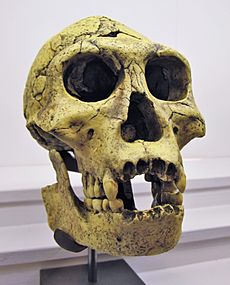

Prehistoric period

Evidence for the earliest occupation of the territory of present-day Georgia goes back to c. 1.8 million years ago, as evident from the excavations of Dmanisi in the south-eastern part of the country. This is the oldest evidence of humans in Europe. Later prehistoric remains (Acheulian, Mousterian and the Upper Palaeolithic) are known from numerous cave and open-air sites in Georgia. The earliest agricultural Neolithic occupation is dated sometime between 6000 and 5000 BC. known as the Shulaveri-Shomu culture, where people used local obsidian for tools, raised animals such as cattle and pigs, and grew crops, including grapes. Numerous excavations in tell settlements of the Shulaveri-Shomu type have been conducted since the 1960s. The earliest evidence of wine to date has been found in Georgia, where 8000-year old wine jars were uncovered.

Early metallurgy started in Georgia during the 6th millennium BC, associated with the Shulaveri-Shomu culture. From the beginning of the 4th millennium, metals became used to larger extend in East Georgia and in the whole Transcaucasian region. In the 1970s, archaeological excavations revealed a number of ancient settlements that included houses with galleries, carbon-dated to the 5th millennium BC in the Imiris-gora region of Eastern Georgia. These dwellings were circular or oval in plan, a characteristic feature being the central pier and chimney. These features were used and further developed in building Georgian dwellings and houses of the 'Darbazi' type. In the Chalcolithic period of the fourth and third millennia BC, Georgia and eastern Asia Minor were home to the Kura-Araxes culture, giving way in the second millennium BC. to the Trialeti culture. Archaeological excavations have brought to light the remains of settlements at Beshtasheni and Ozni (4th–3rd millennium BC), and barrow burials (carbon dated to the 2nd millennium BC) in the province of Trialeti, at Tsalka (Eastern Georgia). Together, they testify to an advanced and well-developed culture of building and architecture.

Diauehi, a tribal union of early-Georgians, first appear in written history in the 12th century BC. Archaeological finds and references in ancient sources reveal elements of early political and state formations characterized by advanced metallurgy and goldsmith techniques that date back to the 7th century BC and beyond. Between 2100 and 750 BC, the area survived the invasions by the Hittites, Urartians, Medes, Proto-Persians and Cimmerians. At the same period, the ethnic unity of Proto-Kartvelians broke up into several branches, among them Svans, Zans/Chans and East-Kartvelians. That finally led to the formation of modern Kartvelian languages: Georgian (originating from East Kartvelian vernaculars), Svan, Megrelian and Laz (the latter two originating from Zan dialects). By that time Svans were dominant in modern Svaneti and Abkhazia, Zans inhabited modern Georgian province of Samegrelo, while East-Kartvelians formed the majority in modern eastern Georgia. As a result of cultural and geographic delimitation, two core areas of future Georgian culture and statehood formed in western and eastern Georgia by the end of the 8th century BC. The first two Georgian states emerged in the west known as the Kingdom of Colchis and in the east as the Kingdom of Iberia.

Antiquity

The classical period saw the rise of a number of early Georgian states, the principal of which was Colchis in the west and Iberia in the east. In the 4th century BC, a unified kingdom of Georgia – an early example of advanced state organization under one king and an aristocratic hierarchy – was established.

In Greek mythology, Colchis was home to sorceress Medea and held the famous Golden Fleece, sought by Jason and the Argonauts in the epic tale Argonautica. According to Strabo and several modern scholars, the incorporation of the Golden Fleece into the myth may have derived from the western Georgian practice of using fleeces to sift gold dust from the mountain rivers. Known to its natives as Egrisi or Lazica, Colchis was also the battlefield of the Lazic War fought between the Byzantine Empire and Sassanid Persia.

In 66 BC, the Roman Empire completed its conquest of the Caucasus region, incorporating Colchis into the Empire as one of its provinces. The political arrangement was different in Colchis' eastern counterpart – Iberia was invaded by Rome but became a vassal kingdom, rather than an integral province. Vassalage proved beneficial to Iberia because it enjoyed significant independence and, with the lowlands frequently raided by fierce mountain tribes, paying a nominal homage to Rome in exchange for protection was viewed as a worthwhile investment. As a result of these processes, the early Georgian kingdoms were intermittently Roman client states and allies for nearly 400 years.

From the first centuries A.D, the cult of Mithras, Greco-Roman mysteries, paganism, Zoroastrianism, idolatry, and various local mythical beliefs were commonly practiced in Georgia. In the 4th century, a Greek-speaking Roman woman, Saint Nino, began preaching Christianity in the kingdom. Having cured the queen of a mysterious illness and convinced her to accept Christianity, St. Nino managed to convert King Mirian, as well. In 337 AD, Mirian officially declared Christianity as the state religion, a move which gave great stimulus to the development of Georgian literature, arts, and ultimately playing a key role in the formation of the unified Georgian nation. King Mirian's acceptance of Christianity effectively tied the kingdom to the neighboring Eastern Roman Empire, which exerted a strong influence on Georgia for nearly a millennium, determining much of its present cultural identity.

Medieval Georgia and the Georgian Golden Age

Unification of the Georgian State

The first decades of the 9th century saw the rise of a new Georgian state in Tao-Klarjeti. Ashot Courapalate of the royal family of Bagrationi liberated from the Arabs the territories of former southern Iberia. These included the Principalities of Tao and Klarjeti, and the Earldoms of Shavsheti, Khikhata, Samtskhe, Trialeti, Javakheti and Ashotsi, which were formally a part of the Byzantine Empire, under the name of "Curopalatinate of Iberia". In practice, however, the region functioned as a fully independent country with its capital in Artanuji. The hereditary title of Curopalates was kept by the Bagrationi family, whose representatives ruled Tao-Klarjeti for almost a century. Curopalate David Bagrationi expanded his domain by annexing the city of Theodossiopolis (Karin, Karnukalaki) and the Armenian province of Basiani, and by imposing a protectorate over the Armenian provinces of Kharqi, Apakhuni, Mantsikert, and Khlat, formerly controlled by the Kaysite Arab Emirs.

The first united Georgian monarchy was formed at the end of the 10th century when Curopalate David invaded the Earldom of Kartli-Iberia. Three years later, after the death of his uncle Theodosius the Blind, King of Egrisi-Abkhazia, Bagrat III inherited the Abkhazian throne. In 1001 Bagrat added Tao-Klarjeti (Curopalatinate of Iberia) to his domain as a result of David's death. In 1008–1010, Bagrat annexed Kakheti and Ereti, thus becoming the first king of a united Georgia in both the east and west.

The second half of the 11th century was marked by the strategically significant invasion of the Seljuq Turks, who by the end of the 1040s had succeeded in building a vast nomadic empire including most of Central Asia and Persia. In 1071, the Seljuq army destroyed the united Byzantine-Armenian and Georgian forces in the Battle of Manzikert. By 1081, all of Armenia, Anatolia, Mesopotamia, Syria, and most of Georgia had been conquered and devastated by the Seljuqs in the Great Turkish Invasion. In Georgia, only the mountainous areas of Abkhazia, Svaneti, Racha, and Khevi–Khevsureti remained out of Seljuq control and served as a relatively safe havens for numerous refugees. The rest of the country was dominated by the conquerors who destroyed the cities and fortresses, looted the villages, and massacred both the aristocracy and the farming population. In fact, by the end of the 1080s, Georgians were outnumbered in the region by the invaders.

David IV

The reign of David IV ("the builder" or "the great") marked the beginning of the Georgian Golden Age. The son of George II and Queen Helena, David assumed the throne at the age of 16 in a period of Great Turkish Invasions. As he came of age under the guidance of his court minister, George of Chqondidi, David IV suppressed dissent of feudal lords and centralized the power in his hands to effectively deal with foreign threats. In 1121, he decisively defeated much larger Turkish armies during the Battle of Didgori, with fleeing Seljuq Turks being run down by pursuing Georgian cavalry for several days. A huge amount of booty and prisoners were captured by David's army, which had also secured Tbilisi and inaugurated a new era of revival.

To highlight his country's higher status, he became the first Georgian king to reject the highly respected titles bestowed by the Eastern Roman Empire, Georgia’s longtime ally, indicating that Georgia would deal with its powerful friend only on a parity basis. Due to close family ties between Georgian and Byzantine royalty - Princess Martha of Georgia, aunt of David IV, was once a Byzantine Empress Consort - by 11th century as many as 16 Georgian ruling princes and kings had held Byzantine titles, David becoming the last one to do so.

David IV made particular emphasis on removing the vestiges of unwanted eastern influences, which the Georgians considered forced, in favor of the traditional Christian and Byzantine overtones. As part of this effort he founded the Gelati Monastery, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, which became an important center of scholarship in the Eastern Orthodox Christian world of that time.

David also played a personal role in reviving Georgian religious hymnography, composing the Hymns of Repentance (Georgian: [გალობანი სინანულისანი, galobani sinanulisani] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), a sequence of eight free-verse psalms. In this emotional repentance of his sins, David sees himself as reincarnating the Biblical David, with a similar relationship to God and to his people. His hymns also share the idealistic zeal of the contemporaneous European crusaders to whom David was a natural ally in his struggle against the Seljuks.

Reigns of Demetrius I and George III

The kingdom continued to flourish under Demetrius I, the son of David. Although his reign saw a disruptive family conflict related to royal succession, Georgia remained a centralized power with a strong military, with several decisive victories against the Muslims in Ganja, gates of which were captured by Demetrius and moved as a trophy to Gelati.

A talented poet, Demetrius also continued his father's contributions to Georgia's religious polyphony. The most famous of his hymns is Thou Art a Vineyard, which is dedicated to Virgin Mary, the patron saint of Georgia, and is still sung in Georgia's churches 900 years after its creation.

Demetrius was succeeded by his son George in 1156, beginning a stage of more offensive foreign policy. The same year he ascended to the throne, George launched a successful campaign against the Seljuq sultanate of Ahlat. He freed the important Armenian town of Dvin from Turkish vassalage and was thus welcomed as a liberator in the area. George also continued the process of intermingling Georgian royalty with the highest ranks of the Eastern Roman Empire, testament of which is the marriage of his daughter Rusudan to Manuel Komnenos, the son of Emperor Andronikos I Komnenos.

Zenith of development under Queen Tamar

The successes of his predecessors were built upon by Queen Tamar, daughter of George III, who became the first female ruler of Georgia in her own right and under whose leadership the Georgian state reached the zenith of power and prestige in the Middle Ages. She not only shielded much of her Empire from further Turkish onslaught but successfully pacified internal tensions, including a coup organized by her Russian husband Yury Bogolyubsky, prince of Novgorod. Additionally, she pursued policies that were considered very enlightened for her time period, such as abolishing state-sanctioned death penalty and torture.

Foreign interventions and dealings in the Holy Land

Among the remarkable events of Tamar's reign was the foundation of the empire of Trebizond on the Black Sea in 1204. This state was established in the northeast of the crumbling Byzantine Empire with the help of the Georgian armies, which supported Alexios I of Trebizond and his brother, David Komnenos, both of whom were Tamar's relatives. Alexios and David were fugitive Byzantine princes raised at the Georgian court. According to Tamar's historian, the aim of the Georgian expedition to Trebizond was to punish the Byzantine emperor Alexius IV Angelus for his confiscation of a shipment of money from the Georgian queen to the monasteries of Antioch and Mount Athos. Tamar's Pontic endeavor can also be explained by her desire to take advantage of the Western European Fourth Crusade against Constantinople to set up a friendly state in Georgia's immediate southwestern neighborhood, as well as by the dynastic solidarity to the dispossessed Comnenoi.

The country's power had grown to such extent that in the later years of Tamar's rule, the Kingdom was primarily concerned with the protection of the Georgian monastic centers in the Holy Land, eight of which were listed in Jerusalem. Saladin's biographer Bahā' ad-Dīn ibn Šaddād reports that, after the Ayyubid conquest of Jerusalem in 1187, Tamar sent envoys to the sultan to request that the confiscated possessions of the Georgian monasteries in Jerusalem be returned. Saladin's response is not recorded, but the queen's efforts seem to have been successful. Ibn Šaddād furthermore claims that Tamar outbid the Byzantine emperor in her efforts to obtain the relics of the True Cross, offering 200,000 gold pieces to Saladin who had taken the relics as booty at the battle of Hattin – to no avail, however.

Jacques de Vitry, the Patriarch of Jerusalem at that time wrote:

There is also in the East another Christian people, who are very warlike and valiant in battle, being strong in body and powerful in the countless numbers of their warriors...Being entirely surrounded by infidel nations...these men are called Georgians, because they especially revere and worship St. George...Whenever they come on pilgrimage to the Lord's Sepulchre, they march into the Holy City...without paying tribute to anyone, for the Saracens dare in no wise molest them...

Commerce and culture

With flourishing commercial centers now under Georgia's control, industry and commerce brought new wealth to the country and Tamar's court. Tribute extracted from the neighbors and war booty added to the royal treasury, giving rise to the saying that "the peasants were like nobles, the nobles like princes, and the princes like kings."

Tamar's reign also marked the continuation of artistic development in the country commenced by her predecessors. While her contemporary Georgian chronicles continued to enshrine Christian morality, the religious theme started to lose its earlier dominant position to the highly original secular literature. This trend culminated in an epic written by Georgia's national poet Rustaveli - The Knight in the Panther's Skin (Vepkhistq'aosani). Revered in Georgia as the greatest achievement of native literature, the poem celebrates the Medieval humanistic ideals of chivalry, friendship and courtly love.

Nomadic invasions and the gradual decline of Georgia

Around the time when Mongols invaded Slavic northeast of Europe, the nomadic hordes simultaneously pushed down south to Georgia. George IV, son of Queen Tamara, put aside his preparations in support of the Fourth Crusade and concentrated on fighting the invaders, but the Mongol onslaught was too strong to overcome. Georgians suffered heavy losses in the war and the king himself was severely wounded. As a result, George became handicapped and died prematurely at the age of 31.

George's sister Rusudan assumed the throne but she was too inexperienced and her country too weakened to push out the nomads. In 1236 a prominent Mongol commander Chormaqan led a massive army against Georgia and its vassals, forcing Queen Rusudan to flee to the west, leaving eastern Georgia in the hands of noblemen who eventually made peace with the Mongols and agreed to pay tribute; those who resisted were subject to complete annihilation. The Mongol armies chose not to cross the natural barrier of Likhi Range in pursuit of the Georgian Queen, sparing western Georgia of the widespread rampages. Later, Rusudan attempted to gain support from Pope Gregory IX, but without any success. In 1243, Georgia was finally forced to acknowledge the Great Khan as its overlord.

Perhaps no Mongol invasion devastated Georgia as much as the decades of anti-Mongol struggle that took place in the country. The first anti-Mongol uprising started in 1259 under the leadership of David VI and lasted for almost thirty years. The anti-Mongol strife continued without much success under Kings Demetrius the Self-Sacrificer, who was executed by the Mongols, and David VIII.

Georgia finally saw a period of revival unknown since the Mongol invasions under King George V the Brilliant. A far-sighted monarch, George V managed to play on the decline of the Ilkhanate, stopped paying tribute to the Mongols, restored the pre-1220 state borders of Georgia, and returned the Empire of Trebizond into Georgia's sphere of influence. Under him, Georgia established close international commercial ties, mainly with the Byzantine Empire - to which George V had family ties - but also with the great European maritime republics, Genoa and Venice. George V also achieved the restoration of several Georgian monasteries in Jerusalem to the Georgian Orthodox Church and gained free passage for Georgian pilgrims to the Holy Land. The widespread use of the Jerusalem cross in Medieval Georgia - an inspiration for the modern national flag of Georgia - is thought to date to the reign of George V.

The death of George V, the last of great kings of unified Georgia, precipitated an irreversible decline of the Kingdom. The following decades were marked by Black Death, which was spread by the nomads, as well as numerous invasions under the leadership of Tamerlane, who devastated the country's economy, population, and urban centers. After the fall of Byzantium, Georgia definitively turned into an isolated, fractured Christian enclave, a relic of the faded East Roman epoch surrounded by hostile Turco-Iranic neighbors.

Early modern period

External domination

In the 15th century the whole area changed dramatically in all possible aspects: linguistic, cultural, political, etc. During that period the Kingdom of Georgia turned into an isolated, fractured Christian enclave, a relic of the faded East Roman epoch surrounded by a Muslim, predominantly Turco-Iranian world. During the three subsequent centuries, the Georgian rulers maintained their perilous autonomy as subjects under the Turkish Ottoman and Iranian Safavid, Afsharid, and Qajar domination, although sometimes serving as little more than puppets in the hands of their powerful suzerains.

By the middle of the 15th century, most of Georgia's old neighbor-states disappeared from the map within less than a hundred years. The fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453 sealed the Black Sea and cut the remnants of Christian states of the area from Europe and the rest of the Christian world. Georgia remained connected to the West through contact with the Genoese colonies of the Crimea.

As a result of these changes, the Georgian Kingdom suffered economic and political decline and in the 1460s the kingdom fractured into several kingdoms and principalities:

- 3 Kingdoms of Kartli, Kakheti and Imereti.

- 5 Principalities of Guria, Svaneti, Meskheti, Abkhazeti and Samegrelo.

By the late 15th century the Ottoman Empire was encroaching on the Georgian states from the west and in 1501 a new Muslim power, Safavid Iran, arose to the east. For the next few centuries, Georgia would become a battleground between these two great rival powers and the Georgian states would struggle to maintain their independence by various means. Ottoman and Safavid Iranian encroachments started for the Ottomans in the late 15th century, and for the Safavids in the earliest 16th century in which the latter managed to make eastern Georgia a vassal in 1500. In 1555, the Ottomans and the Safavids signed the Peace of Amasya following the Ottoman–Safavid War (1532–55), defining spheres of influence in Georgia, assigning Imereti in the west to the Turks and Kartli-Kakheti in the east to the Persians. The treaty however, was not in force for long as the Ottomans gained the upper hand and launched campaigns during the next Ottoman-Safavid war threatening to end the Persian domination in the region. The Safavid Persians reestablished their hegemony over all lost regions some two decades later including full hegemony over most of Georgia in the Ottoman–Safavid War (1603–18).

Since at least the mid-15th century, rulers in both western and eastern Georgian kingdoms have repeatedly sought aid from Western European powers to no avail. A notable episode of this type of effort was spearheaded in the early 1700s by a Georgian diplomat Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani, who was sent by his former pupil, King Vakhtang VI, to France and the Vatican in order to secure assistance for Georgia. Orbeliani was well received by King Louis XIV and Pope Clement XI, but no tangible assistance could be secured. Lack of Western assistance not only left Georgia exposed but sealed the personal fates of Orbeliani and King Vakhtang - pushed by the invading Ottoman army, both were eventually forced to accept the offer of protection from Peter the Great and escaped to Russia, from where they never returned. In modern-day Georgia, the story of Orbeliani's diplomatic mission to France would become a symbol of how the West neglects Georgian appeals for protection.

After the Ottomans utter failure to gain permanent foothold in the eastern Caucasus, Iranians immediately sought to strengthen their position and finally subject the rebellious Kingdoms of Eastern Georgia and making them integral parts of the empire. During the next 150 years as Persian subjects, various Georgian kings and nobles rose into rebellion, while at many other times political activity was nothing but dormant, and many kings and aristocrats fully accepted Persian overlordship and converted to Islam as well, for greater boons from their Iranian Shahs. On the maternal side of the Safavid (also Qajar) and the Ottoman Turkish dynasty, many members were from Georgian aristocratic or different lines.

In the early 17th century Shah Abbas I made a punitive campaign into his Georgian territories after being informed that Teimuraz I of Kakheti with a couple of Christian citizens assaulted the Karabakh governor and killed him. Shah Abbas decided to confront him but Teimuraz I fled to Georgia towards Ahmed I, in order to shelter from Safavid forces. This event brought an end to the Treaty of Nasuh Pasha signed between the Ottomans and the Safavids. In 1616, Abbas I dispatched his troops to Georgia. He aimed to suppress the Georgian revolt in Tbilisi, however the Safavid soldiers met heavy resistance by the citizens of Tbilisi. Enraged, Shah Abbas ordered a massacre of the public. A large number of Georgian soldiers and people were killed and as many as between 130,000 and 200,000 Georgians from Kakheti were deported to Persia. During the same conflict, Teimuraz sent the Queen mother, Ketevan, as a negotiator to Abbas, but in an act of revenge for the recalcitrance of Teimuraz, he ordered the queen to renounce Christianity, and upon her refusal, killed her. By the 17th century, both eastern and western Georgia had sunk into poverty as the result of the constant warfare. The economy was so bad that barter replaced the use of money and the populations of the cities declined markedly. The French traveller Jean Chardin, who visited the region of Mingrelia in 1671, noted the wretchedness of the peasants, the arrogance of the nobles and the ignorance of the clergy.

Russo-Georgian relations before 1801

By the 16th century, the Kingdom of Georgia had become fractured into a series of smaller states, which were fought over by the two great Muslim empires in the region, Ottoman Turkey and Persia. Soon, however, the Russian state of Muscovy emerged as a third imperial power in the region. Because Russia shared Georgia's Orthodox religion, Georgia was increasingly looking north for support. Diplomatic contacts between Georgia and Moscow began in 1558 and in 1589, Tsar Fyodor II offered to put the kingdom under his protection. Yet, little help was forthcoming and the Russians were still too remote from Georgia to effectively challenge Ottoman hegemony. Only in the early 18th century did Russia start to make serious military inroads south of the Caucasus. In 1722, Peter the Great exploited the chaos and turmoil in Persia to lead an expedition against it, while he struck an alliance with the Georgian monarch Vakhtang VI. However, the Georgian and Russian armies failed to link up and the Russians retreated northward again, leaving Georgia at the mercy of the Persians. Vakhtang ended his days in exile in Russia.

Vakhtang's successor, Heraclius II of Georgia, turned towards Russia for protection against Ottoman and Persian attacks. The kings of the other major Georgian state, Imereti (in Western Georgia), also contacted Russia, seeking protection against the Ottomans. The Russian empress Catherine the Great was keen to have the Georgians as allies in her wars against the Turks and Persians, but sent only meagre forces to help them. In 1769-1772, a handful of Russian troops under General Totleben battled against Turkish invaders in Imereti and Kartl-Kakheti. In 1783, Heraclius signed the Treaty of Georgievsk with Russia, according to which Kartli-Kakheti agreed to forswear allegiance to any state except Russia, in return for Russian protection. But when another Russo-Turkish War broke out in 1787, the Russians withdrew their troops from the region for use elsewhere, leaving Georgia unprotected. In 1795, the new Persian shah, Agha Mohammed Khan issued an ultimatum to Heraclius, ordering him to break off relations with Russia or face invasion. Heraclius ignored it, counting on Russian help, which did not arrive. Agha Muhammad Khan carried out his threat and captured and burned the capital, Tbilisi, to the ground.

The Russian annexations

Eastern Georgia

Following Heraclius II’s death, the Georgian throne was transferred to his sickly and ineffectual son George XII, who died just two years later in 1800. George’s death plunged the kingdom into a succession battle of two rival heirs, David and Iulon. Tsar Paul I of Russia, however, had already decided that neither candidate would be crowned king. Instead, the monarchy would be abolished and the country administered by Russia. He signed a decree on the incorporation of Eastern Georgia into the Russian Empire which was confirmed by Tsar Alexander I on 12 September 1801. The Georgian envoy in Saint Petersburg, Garsevan Chavchavadze, reacted with a note of protest that was presented to the Russian vice-chancellor Alexander Kurakin. In May 1801, Russian General Carl Heinrich von Knorring removed the Georgian heir to the throne, Davit Batonishvili, from power and deployed a provisional government headed by General Ivan Petrovich Lazarev. Knorring had secret orders to remove all the male and some female members of the royal family to Russia. Some of the Georgian nobility did not accept the decree until April 1802, when General Knorring held the nobility in Tbilisi's Sioni Cathedral and forced them to take an oath on the imperial crown of Russia. Those who disagreed were temporarily arrested.

Now that Russia was able to use Georgia as a bridgehead for further expansion south of the Caucasus, Persia and the Ottoman Empire felt threatened. In 1804, Pavel Tsitsianov, the Georgian commander of Russian forces in the Caucasus, attacked Ganja, provoking the Russo-Persian War of 1804-1813. This was followed by the Russo-Turkish War of 1806-12 with the Ottomans, who were unhappy with Russian expansion in Western Georgia. Both wars ended in Russian victory, with the Ottomans and Persians recognising the tsar's claims over Georgia (by the Treaty of Bucharest with Turkey and the Treaty of Gulistan with Persia).

Western Georgia

Solomon II of Imereti was angry at the Russian annexation of Kartli-Kakheti. He offered a compromise: he would make Imereti a Russian protectorate if the monarchy and autonomy of his neighbour was restored. Russia made no reply. In 1803, the ruler of Mingrelia, a region belonging to Imereti, rebelled against Solomon and acknowledged Russia as his protector instead. When Solomon refused to make Imereti a Russian protectorate too, the Russian general Tsitsianov invaded and on 25 April 1804, Solomon signed a treaty making him a Russian vassal.

However, Solomon was far from submissive. When war broke out between the Ottomans and Russia, Solomon started secret negotiations with the former. In February 1810, a Russian decree proclaimed that Solomon was dethroned and ordered Imeretians to pledge allegiance to the tsar. A large Russian army invaded the country, but many Imeretians fled to the forests to start a resistance movement. Solomon hoped that Russia, distracted by its wars with the Ottomans and Persia, would allow Imereti to become autonomous. The Russians eventually crushed the guerrilla uprising but they could not catch Solomon. However, Russia's peace treaties with Ottoman Turkey (1812) and Persia (1813) put an end to the king's hopes of foreign support (he had also tried to interest Napoleon). Solomon died in exile in Trabzon in 1815.

In 1828-29, another Russo-Turkish War ended with Russia adding the major port of Poti and the fortress towns of Akhaltsikhe and Akhalkalaki to its possessions in Georgia. From 1803 to 1878, as a result of numerous Russian wars now against Ottoman Turkey, several of Georgia's previously lost territories – such as Adjara – were also incorporated into the empire. The principality of Guria was abolished and incorporated into the Empire in 1829, while Svaneti was gradually annexed in 1858. Mingrelia, although a Russian protectorate since 1803, was not absorbed until 1867.

Modern history

Russian Empire

The Russian and Georgian societies had much in common: the main religion was Orthodox Christianity and in both countries a land-owning aristocracy ruled over a population of serfs. The Russian authorities aimed to integrate Georgia into the rest of their empire, but at first Russian rule proved high-handed, arbitrary and insensitive to local law and customs, leading to a conspiracy by Georgian nobles in 1832 and a revolt by peasants and nobles in Guria in 1841.

Things changed for better with the appointment of Mikhail Vorontsov as Viceroy of the Caucasus in 1845. Count Vorontsov's new policies won over the Georgian nobility, who increasingly adopted Western European customs and attire, as the Russian nobility had done in the previous century. Life for Georgian serfs was very different, however, since the rural economy remained seriously depressed. Georgian serfs lived in dire poverty, subject to the frequent threat of starvation. Few of them lived in the towns, where what little trade and industry there was, was in the hands of Armenians, whose ancestors had migrated to Georgia in the Middle Ages.

Serfdom was abolished in Russian lands in 1861. The tsar also wanted to emancipate the serfs of Georgia, but without losing the loyalty of the nobility whose revenues depended on peasant labour. This called for delicate negotiations before serfdom was gradually phased out in the Georgian provinces from 1864 onwards.

Growth of the national movement

The emancipation of the serfs pleased neither the serfs nor the nobles. The poverty of the serfs had not been alleviated while the nobles had lost some of their privileges. The nobles in particular also felt threatened by the growing power of the urban, Armenian middle class in Georgia, who prospered as capitalism came to the region. Georgian dissatisfaction with Tsarist autocracy and Armenian economic domination led to the development of a national liberation movement in the second half of the 19th century.

A large-scale peasant revolt occurred in 1905, which led to political reforms that eased the tensions for a period. During this time, the Marxist Social Democratic Party became the dominant political movement in Georgia, being elected to all the Georgian seats in the Russian State Duma established after 1905. Josef Vissarionovich Djugashvili (more famously known as Joseph Stalin), a Georgian Bolshevik, became a leader of the revolutionary (and anti-Menshevik) movement in Georgia. He went on to control the Soviet Union.

Many Georgians were upset by the loss of independence of the Georgian Orthodox Church. The Russian clergy took control of Georgian churches and monasteries, prohibiting use of the Georgian liturgy and desecrating medieval Georgian frescos on various churches all across Georgia.

Between the years of 1855 to 1907, the Georgian patriotic movement was launched under the leadership of Prince Ilia Chavchavadze, world-renowned poet, novelist and orator. Chavchavadze financed new Georgian schools and supported the Georgian national theatre. In 1877 he launched the newspaper Iveria, which played an important part in reviving Georgian national consciousness. His struggle for national awakening was welcomed by the leading Georgian intellectuals of that time such as Giorgi Tsereteli, Ivane Machabeli, Akaki Tsereteli, Niko Nikoladze, Alexander Kazbegi and Iakob Gogebashvili.

The Georgian intelligentsia's support for Prince Chavchavadze and Georgian independence is shown in this declaration:

Our patriotism is of course of an entire different kind: it consists solely in a sacred feeling towards our mother land: ... in it there is no hate for other nations, no desire to enslave anybody, no urge to impoverish anybody. Out patriots' desire to restore Georgia's right to self-government and their own civic rights, to preserve their national characteristics and culture, without which no people can exist as a society of human beings.

The last decades of the 19th century witnessed a Georgian literary revival in which writers emerged of a stature unequalled since the Golden Age of Rustaveli seven hundred years before. Ilia Chavchavadze himself excelled alike in lyric and ballad poetry, in the novel, the short story and the essay. Apart from Chavchavadze, the most universal literary genius of the age was Akaki Tsereteli, known as "the immortal nightingale of the Georgian people." Along with Niko Nikoladze and Iakob Gogebashvili, these literary figures contributed significantly to the national cultural revival and were therefore known as the founding fathers of modern Georgia.

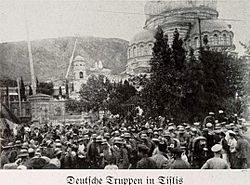

First Republic Under German-British Protection

The Russian Revolution of October 1917 plunged Russia into a bloody civil war during which several outlying Russian territories declared independence. Georgia was one of them, proclaiming the establishment of the independent Democratic Republic of Georgia (DRG) on May 26, 1918. Recognized by all major European powers of the time, DRG was governed by a moderate, multi-party political system led by the Georgian Social Democratic Party (Menshevik), which was in sharp contrast with the "dictatorship of the proletariat" established by the Bolsheviks in Russia.

To maintain its fledgling sovereignty and keep both Russia and Turkey at bay, Georgia became a protectorate of the German Empire, which sent a contingent of troops under the leadership of General Friedrich Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein. The German involvement was short-lived but effective - Berlin pressured Turkey into respecting Georgia's ethnic borders and by July 1918, Turkey handed over all Georgian ports and railways it had controlled up to that point. Germany also lent millions of Deutschmarks to the new republic. Despite cordial German-Georgian relations, Germany had to retreat from the country shortly after Germans lost in World War I.

Following the German defeat, Georgia came under British protection and influence. A British battalion landed in Poti, Georgia on January 4, 1919 and then Batumi; Britain also took over the management and protection of Georgian railways. Britain's involvement was much different from that of their German counterparts - the sole aim of London's costly intervention was to prevent Bolshevik Russia from acquiring oil fields near Baku and the British General Cooke-Collins appeared to care little as to what happened inside Georgia. There was minimal British investment during this time and much emphasis was made on securing pipelines, trade and natural resources. As a result of this myopic attitude, the British were less liked than the Germans formerly stationed in Georgia, nevertheless, the locals continued to view Britain's presence as a stabilizing force.

The somewhat negative perception of Britain began to change with the appointment of Sir Oliver Wardrop as Ambassador to Tbilisi. Wardrop was much loved by the locals ever since his service as the British consul in the Russian Imperial Georgia throughout the 1880s and 1890s. Wardrop had learned the Georgian language earlier in his career and was a prolific translator of Georgian works. The diplomat's sister, Marjory Wardrop, was herself a scholar of Georgia who brought awareness of the Georgian culture to Britain by producing the first prosaic English translation of the Georgian epic poem The Knight in the Panther's Skin. British presence coincided with a number of important events. The Georgian–Armenian War, which erupted over parts of Georgia populated by Armenians, ended in truce due to British intervention. In 1918–1919, Georgian general Giorgi Mazniashvili led an attack against the White Army led by Moiseev and Denikin in order to claim the Black Sea coastline from Tuapse to Sochi and Adler for independent Georgia.

Georgian-Armenian War (1918)

During the final stages of World War I, the Armenians and Georgians had been defending against the advance of the Ottoman Empire. In June 1918, in order to forestall an Ottoman advance on Tiflis, the Georgian troops had occupied the Lori Province, which at the time had a 75% Armenian majority. After the Armistice of Mudros and the withdrawal of the Ottomans, the Georgian forces remained. Georgian Menshevik parliamentarian Irakli Tsereteli offered that the Armenians would be safer from the Turks as Georgian citizens. The Georgians offered a quadripartite conference including Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus in order to resolve the issue, which the Armenians rejected. In December 1918, the Georgians were confronting a rebellion chiefly in the village of Uzunlar in the Lori region. Within days, hostilities commenced between the two republics.

The Georgian-Armenian War was a border war fought in 1918 between the Democratic Republic of Georgia and the Democratic Republic of Armenia over the parts of then disputed provinces of Lori, Javakheti, which had been historically bicultural Armenian-Georgian territories, but were largely populated by Armenians in the 19th century.

Red Army invasion (1921)

In February 1921, the Red Army invaded Georgia and after a short war occupied the country. The Georgian government was forced to flee. Guerrilla resistance in 1921–1924 was followed by a large-scale patriotic uprising in August 1924. Colonel Kakutsa Cholokashvili was one of the most prominent guerrilla leaders in this phase.

Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic (1921–1990)

During the Georgian Affair of 1922, Georgia was forcibly incorporated into the Transcaucasian SFSR comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia (including Abkhazia and South Ossetia). The Soviet Government forced Georgia to cede several areas to Turkey (the province of Tao-Klarjeti and part of Batumi province), Azerbaijan (the province of Hereti/Saingilo), Armenia (the Lore region) and Russia (northeastern corner of Khevi, eastern Georgia). Soviet rule was harsh: about 50,000 people were executed and killed in 1921–1924, more than 150,000 were purged under Stalin and his secret police chief, the Georgian Lavrenty Beria in 1935–1938, 1942 and 1945–1951. In 1936, the TFSSR was dissolved and Georgia became the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Reaching the Caucasus oilfields was one of the main objectives of Adolf Hitler's invasion of the USSR in June 1941, but the armies of the Axis powers did not get as far as Georgia. The country contributed almost 700,000 fighters (350,000 were killed) to the Red Army, and was a vital source of textiles and munitions. However, a number of Georgians fought on the side of the German armed forces, forming the Georgian Legion.

During this period Stalin ordered the deportation of the Chechen, Ingush, Karachay and the Balkarian peoples from the Northern Caucasus; they were transported to Siberia and Central Asia for alleged collaboration with the Nazis. He abolished their respective autonomous republics. The Georgian SSR was briefly granted some of their territory until 1957.

Stalin's successful appeal for patriotic unity eclipsed Georgian nationalism during the war and diffused it in the years following. On March 9, 1956, about a hundred Georgian students were killed when they demonstrated against Nikita Khrushchev's policy of de-Stalinization.

The decentralisation program introduced by Khrushchev in the mid-1950s was soon exploited by Georgian Communist Party officials to build their own regional power base. A thriving pseudo-capitalist shadow economy emerged alongside the official state-owned economy. While the official growth rate of the economy of the Georgia was among the lowest in the USSR, such indicators as savings level, rates of car and house ownership were the highest in the Union, making Georgia one of the most economically successful Soviet republics. Corruption was at a high level. Among all the union republics, Georgia had the highest number of residents with high or special secondary education.

Although corruption was hardly unknown in the Soviet Union, it became so widespread and blatant in Georgia that it came to be an embarrassment to the authorities in Moscow. Eduard Shevardnadze, the country's interior minister between 1964 and 1972, gained a reputation as a fighter of corruption and engineered the removal of Vasil Mzhavanadze, the corrupt First Secretary of the Georgian Communist Party. Shevardnadze ascended to the post of First Secretary with the blessings of Moscow. He was an effective and able ruler of Georgia from 1972 to 1985, improving the official economy and dismissing hundreds of corrupt officials.

Soviet power and Georgian nationalism clashed in 1978 when Moscow ordered revision of the constitutional status of the Georgian language as Georgia's official state language. Bowing to pressure from mass street demonstrations on April 14, 1978, Moscow approved Shevardnadze's reinstatement of the constitutional guarantee the same year. April 14 was established as a Day of the Georgian Language.

Shevardnadze's appointment as Soviet Foreign Minister in 1985 brought his replacement in Georgia by Jumber Patiashvili, a conservative and generally ineffective Communist who coped poorly with the challenges of perestroika. Towards the end of the late 1980s, increasingly violent clashes occurred between the Communist authorities, the resurgent Georgian nationalist movement and nationalist movements in Georgia's minority-populated regions (notably South Ossetia). On April 9, 1989, Soviet troops were used to break up a peaceful demonstration at the government building in Tbilisi. Twenty Georgians were killed and hundreds wounded and poisoned. The event radicalised Georgian politics, prompting many—even some Georgian communists—to conclude that independence was preferable to continued Soviet rule.

Independent Georgia

Gamsakhurdia presidency (1991-1992)

Opposition pressure on the communist government was manifested in popular demonstrations and strikes, which ultimately resulted in an open, multiparty and democratic parliamentary election being held on 28 October 1990 in which the Round Table/Free Georgia bloc captured 54 percent of the proportional vote to gain 155 seats out of the 250 up for election, while the communists gained 64 seats and 30 percent of the proportional vote. The leading dissident Zviad Gamsakhurdia became the head of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Georgia. On March 31, 1991, Gamsakhurdia wasted no time in organising a referendum on independence, which was approved by 98.9% of the votes. Formal independence from the Soviet Union was declared on April 9, 1991, although it took some time before it was widely recognised by outside powers such as the United States and European countries. Gamsakhurdia's government strongly opposed any vestiges of Russian dominance, such as the remaining Soviet military bases in the republic, and (after the dissolution of the Soviet Union) his government declined to join the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

Gamsakhurdia was elected president on May 26, 1991, with 86% of the vote. He was subsequently widely criticised for what was perceived to be an erratic and authoritarian style of government, with nationalists and reformists joining forces in an uneasy anti-Gamsakhurdia coalition. A tense situation was worsened by the large amount of ex-Soviet weaponry available to the quarreling parties and by the growing power of paramilitary groups. The situation came to a head on December 22, 1991, when armed opposition groups launched a violent military coup d'état, besieging Gamsakhurdia and his supporters in government buildings in central Tbilisi. Gamsakhurdia managed to evade his enemies and fled to the breakaway Russian republic of Chechnya in January 1992.

Shevardnadze presidency (1992–2003)

The new government invited Eduard Shevardnadze to become the head of a State Council—in effect, president—in March 1992, putting a moderate face on the somewhat unsavoury regime that had been established following Gamsakhurdia's ouster. In August 1992, a separatist dispute in the Georgian autonomous republic of Abkhazia escalated when government forces and paramilitaries were sent into the area to quell separatist activities. The Abkhaz fought back with help from paramilitaries from Russia's North Caucasus regions and alleged covert support from Russian military stationed in a base in Gudauta, Abkhazia and in September 1993 the government forces suffered a catastrophic defeat, which led to them being driven out and the entire Georgian population of the region being expelled. Around 14,000 people died and another 300,000 were forced to flee.

Ethnic violence also flared in South Ossetia but was eventually quelled, although at the cost of several hundred casualties and 100,000 refugees fleeing into Russian North Ossetia. In south-western Georgia, the autonomous republic of Ajaria came under the control of Aslan Abashidze, who managed to rule his republic from 1991 to 2004 as a personal fiefdom in which the Tbilisi government had little influence.

On September 24, 1993, in the wake of the Abkhaz disaster, Zviad Gamsakhurdia returned from exile to organise an uprising against the government. His supporters were able to capitalise on the disarray of the government forces and quickly overran much of western Georgia. This alarmed Russia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, and units of the Russian Army were sent into Georgia to assist the government. Gamsakhurdia's rebellion quickly collapsed and he died on December 31, 1993, apparently after being cornered by his enemies. In a highly controversial agreement, Shevardnadze's government agreed that it would join the CIS as part of the price for military and political support.

Shevardnadze narrowly survived a bomb attack in August 1995 that he blamed on his erstwhile paramilitary allies. He took the opportunity to imprison the paramilitary leader Jaba Ioseliani and ban his Mkhedrioni militia in what was proclaimed as a strike against "mafia forces". However, his government—and his own family—became increasingly associated with pervasive corruption that hampered Georgia's economic growth. He won presidential elections in November 1995 and April 2000 with large majorities, but there were persistent allegations of vote-rigging.

The war in Chechnya caused considerable friction with Russia, which accused Georgia of harbouring Chechen guerrillas. Further friction was caused by Shevardnadze's close relationship with the United States, which saw him as a counterbalance to Russian influence in the strategic Transcaucasus region. Georgia became a major recipient of US foreign and military aid, signed a strategic partnership with NATO and declared an ambition to join both NATO and the EU. In 2002, the United States sent hundreds of Special Operations Forces to train the Military of Georgia—a programme known as the Georgia Train and Equip Program. Perhaps most significantly, the country secured a $3 billion project for a Caspian-Mediterranean pipeline (Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline)

A powerful coalition of reformists headed by Mikheil Saakashvili and Zurab Zhvania united to oppose Shevardnadze's government in the November 2, 2003 parliamentary elections. The elections were widely regarded as blatantly rigged, including by OSCE observers; in response, the opposition organised massive demonstrations in the streets of Tbilisi. After two tense weeks, Shevardnadze resigned on November 23, 2003, and was replaced as president on an interim basis by Burjanadze.

These results were annulled by the Georgia Supreme Court after the Rose Revolution on November 25, 2003, following allegations of widespread electoral fraud and large public protests, which led to the resignation of Shevardnadze.

Saakashvili presidency (2004-2013)

- 2004 elections

A new election was held on March 28, 2004. The National Movement - Democrats (NMD), the party supporting Mikheil Saakashvili, won 67% of the vote; only the Rightist Opposition (7.6%) also gained parliamentary representation passing the 7% threshold.

On January 4, Mikheil Saakashvili won the Georgian presidential election, 2004 with an overwhelming majority of 96% of the votes cast. Constitutional amendments were rushed through Parliament in February strengthening the powers of the President to dismiss Parliament and creating the post of Prime Minister. Zurab Zhvania was appointed Prime Minister. Nino Burjanadze, the interim President, became Speaker of Parliament.

- First term (2004-2007)

The new president faced many problems on coming to office. More than 230,000 internally displaced persons put an enormous strain on the economy. Peace in the separatist areas of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, overseen by Russian and United Nations peacekeepers in the framework of Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, remained fragile.

The Rose Revolution raised many expectations, both domestically and abroad. The new government was expected to bring democracy, ending a period of widespread corruption and government inefficiency; and to complete state-building by re-asserting sovereignty over the whole Georgian territory. Both aims were very ambitious; the new ruling elite initiated a process of concentration of power in the hands of the executive, in order to use the revolutionary mandate to change the country. In fact, the Saakashvili government initially achieved impressive results in strengthening the capacity of the state and toppling corruption. Georgia's ranking in the Corruption Perceptions Index by Transparency International improved dramatically from rank 133 in 2004 to 67 in 2008 and to 51 in 2012, surpassing several EU countries. But such achievements could only result from the use of unilateral executive powers, failing to achieve consent and initiating a trade-off between democracy-building and state-building.

After the Rose Revolution, relations between the Georgian government and semi-separatist Ajarian leader Aslan Abashidze deteriorated rapidly, with Abashidze rejecting Saakashvili's demands for the writ of the Tbilisi government to run in Ajaria. Both sides mobilised forces in apparent preparations for a military confrontation. Saakashvili's ultimatums and massive street demonstrations forced Abashidze to resign and flee Georgia (2004 Adjara crisis).

Relations with Russia remained problematic due to Russia's continuing political, economic and military support to separatist governments in Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Russian troops still remained garrisoned at two military bases and as peacekeepers in these regions. Saakashvili's public pledge to resolve the matter provoked criticism from the separatist regions and Russia. In August 2004, several clashes occurred in South Ossetia.

On October 29, 2004, the North Atlantic Council (NAC) of NATO approved the Individual Partnership Action Plan of Georgia (IPAP), making Georgia is the first among NATO's partner countries to manage this task successfully.

Georgia supported the coalition forces in Iraq war. On November 8, 2004, 300 extra Georgian troops were sent to Iraq. The Georgian government committed to send a total of 850 troops to Iraq to serve in the protection forces of the UN Mission. Along with increasing Georgian troops in Iraq, the US will train additional 4 thousand Georgian soldiers within frames of the Georgia Train-and-Equip Program (GTEP).

In February 2005 Prime Minister Zurab Zhvania died, and Zurab Nogaideli was appointed as the new Prime Minister. Saakashvili remained under significant pressure to deliver on his promised reforms. Organisations such as Amnesty International have pushed serious concerns over human rights. Discontent over unemployment, pensions and corruption, and the continuing dispute over Abkhazia, have greatly diminished Saakashvili's popularity in the country.

In 2006 Georgia's relationship with Russia was at nadir due to the Georgian-Russian espionage controversy and related events. In 2007, a political crisis led to serious anti-government protests, and Russia allegedly led a series of airspace violations against Georgia.

- 2007 crisis

Since the weakening of the democratic credentials of the Saakashvili cabinet after the police crackdown of the 2007 protests, the government has put the stress on his successful economic reforms. Kakha Bendukidze was pivotal in the libertarian reforms launched under Saakashvili, including one of the least restrictive labour codes, the lowest flat income tax rates (12%) and some of the lowest customs rates worldwide, along with the drastic reduction of necessary licenses and permits for business. The objective of the Georgian elite switched to the aim of "a functioning democracy with the highest possible level of economic liberties", as expressed by the prime minister Lado Gurgenidze.

Saakashvili called new parliamentary and presidential elections for January 2008. In order to contest the presidential election, Saakashvili announced his resignation effective 25 November 2007, with Nino Burjanadze becoming acting president for a second time (until the election returned Saakashvili to office on 20 January 2008).

- Second term (2008-2013)

In August 2008 Russia and Georgia engaged in the 2008 South Ossetia war. Its aftermath, leading to the 2008–2010 Georgia–Russia crisis, is still tense.

In October 2012, Saakashvili admitted defeat for his party in parliamentary elections. In his speech he said that "the opposition has the lead and it should form the government - and I as president should help them with this." This represented the first democratic transition of power in Georgia's post-Soviet history.

Margvelashvili presidency (2013-present)

On 17 November 2013, Giorgi Margvelashvili won the Georgian presidential election, 2013 with 62.12% of the votes cast. With this, a new constitution came into effect which devolved significant power from the President to the Prime Minister. Margvelashvili's inauguration was not attended by his predecessor Mikheil Saakashvili, who cited disrespect by the new government towards its predecessors and opponents.

Margvelashvili initially refused to move to the luxurious presidential palace built under Saakashvili in Tbilisi, opting for more modest quarters in the building of the State Chancellery until a 19th-century building once occupied by the U.S. embassy in Georgia is refurbished for him. However, he later started to occasionally used the palace for official ceremonies. This was one of the reasons for which Margvelashvili was publicly criticized, in a March 2014 interview with Imedi TV, by the ex-Prime Minister Ivanishvili, who said he was "disappointed" in Margvelashvili.

Images for kids

-

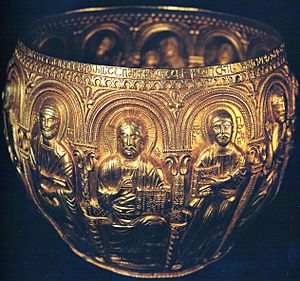

Patera depicting Marcus Aurelius uncovered in central Georgia, 2nd century AD

-

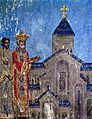

King Mirian III established Christianity in Georgia as the official state religion in 324.

-

The construction of Svetitskhoveli Cathedral in Mtskheta, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, was initiated in the 1020s by George I.

-

Დავით აღმაშენებელი - David Aghmashenebeli.jpg

King David the Builder, one of Georgia's greatest kings.

-

Queen Tamar and her father King George III, fresco from Vardzia.

-

Queen Tamar of Georgia, titled as "Mepe" (King).

-

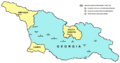

Kingdom of Georgia during its Golden Age.

-

Royal armour of King Alexander III, early 1600s.

-

King Solomon I

-

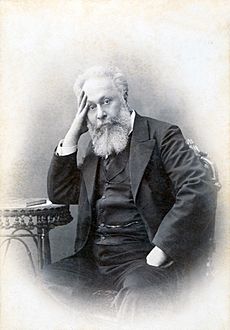

Prince Ilia Chavchavadze, leader of the Georgian national revival in the 1860s.

-

Prince Akaki Tsereteli, prominent Georgian poet and national liberation movement figure.

-

British troops marching in Batumi, Georgia in 1920. Following World War I, Britain replaced German troops in Georgia

-

The Democratic Republic of Georgia before its conquest by the Soviet Union.

-

Georgian SSR in 1957–1991, including Abkhazian Autonomous SSR, Adjara ASSR, and South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast.

-

Presidents Barack Obama and Mikheil Saakashvili.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Georgia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Georgia para niños