Yup'ik facts for kids

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 34,000 (2010 U.S. Census) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (Alaska) |

34,000 |

| Languages | |

| Yup'ik (and dialects: Cup'ik, Cup'ig), English, Russian | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (Moravian Protestant, Jesuit Catholic, Russian Orthodox) and Shamanism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Siberian Yupik, Sugpiaq/Alutiiq, Naukan, Iñupiat, Inuit, Aleut | |

The Yup'ik people are an Native group who live in western and southwestern Alaska. Their homeland stretches along the coast of the Bering Sea, including islands like Nelson and Nunivak Island. They also live along the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta and parts of the Alaska Peninsula.

Some Yup'ik people are known by different names depending on their dialect. Those who speak the Chevak Cup'ik dialect are called Cup'ik. People from Nunivak Island who speak the Nunivak Cup'ig dialect are called Cup'ig. Even with these different names, all these groups can understand each other when they speak. The larger term Yup'ik is often used to describe everyone.

The Yup'ik are one of four main Yupik groups in Alaska and Siberia. They are related to the Sugpiaq ~ Alutiiq people, the Siberian Yupik, and the Naukan. Most Yup'ik people speak the Yup'ik language. About 10,000 people out of 21,000 still speak their native language.

Today, Yup'ik people live a mix of modern and traditional lifestyles. They work in modern jobs but still hunt and fish for food in traditional ways. They also gather traditional foods. Many Yup'ik people still speak their language, and schools have offered bilingual education since the 1970s.

The Yup'ik are the largest Alaska Native group. In 2010, about 34,000 people identified as Yup'ik. Their neighbors include the Iñupiaq to the north and the Alutiiq ~ Sugpiaq to the south. Other Alaskan Athabaskans live to the east.

Contents

- What Does "Yup'ik" Mean?

- A Look at Yup'ik History

- Yuuyaraq: The Yup'ik Way of Life

- Yup'ik Society

- Yup'ik Economy and Daily Life

- Yup'ik Culture and Traditions

- Modern Tribal Groups

- Notable Yup'ik People

What Does "Yup'ik" Mean?

The name Yup'ik is commonly used today, though some still use Cup'ik and Cup'ig. The word Yup'ik (plural Yupiit) comes from the Yup'ik word yuk, meaning "person." The ending -pik or -piaq means "real" or "genuine." So, Yup'ik means "real people."

The apostrophe in "Yup'ik" shows that the 'p' sound is longer, which is a special part of their language.

A Look at Yup'ik History

Where Did the Yup'ik Come From?

Experts believe the ancestors of the Yup'ik and Aleut people came from eastern Siberia. They traveled east and reached the Bering Sea area about 10,000 years ago. This happened during times when a land bridge connected Siberia and North America.

Around 3,000 years ago, the ancestors of the Yup'ik settled along the coast of western Alaska. Later, around 1400 C.E., they moved up rivers like the Yukon and Kuskokwim.

Before Russians arrived, the Yup'ik hunted sea animals like seals, walruses, and sea lions. They used weapons made from wood, stone, or bone. Families lived together in large groups during winter and in smaller huts in summer.

The Russian Period (1732-1867)

Russians began exploring and settling parts of North America from 1732 to 1867. They set up hunting and trading posts in the Aleutian Islands and northern Alaska. These posts were mainly for trading furs.

At first, the Russians focused on the Aleutian Islands and Kodiak Island. They sometimes treated the Native people harshly, forcing them to pay taxes in furs. However, the Yup'ik people in the Yukon-Kuskokwim delta were not greatly affected during the early Russian period.

Later, around 1825, infectious diseases brought by Europeans began to affect Alaska Natives. They had no natural protection against these new illnesses. Also, their way of life changed as they started relying more on European goods from the trading posts. Russian Orthodox missionaries also arrived, learning native languages and holding services in them.

The American Period (1867-Today)

The United States bought Alaska from Russia in 1867. In the early American period (1867–1939), the government mostly focused on using Alaska's natural resources.

Christian missions, like the Moravian Protestant and Jesuit Catholic missions, were set up along the Kuskokwim and Yukon rivers. These missions often discouraged or even forbade Native languages in their schools. This meant children were only allowed to speak English.

A very important event was the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) in 1971. This law changed how land was owned and how Native groups were organized in Alaska.

Before Europeans arrived, Yup'ik history was passed down through oral tradition. Storytellers, called qulirarta, shared traditional legends (qulirat) and historical stories (qanemcit). These stories are a vital part of Alaska's early history.

Yuuyaraq: The Yup'ik Way of Life

Yuuyaraq means the Yup'ik way of life as a human being. It covers how people interact with each other, how they get food, their knowledge about nature, and their spiritual balance.

Yuuyaraq taught the right way to think and speak about all living things, especially the animals they hunted for food, clothing, shelter, and tools. These animals were believed to be sensitive and understand human talk, so they needed to be treated with respect. Yuuyaraq also guided how to hunt and fish, and how to handle animals to honor their spirits. This unwritten way of life guided everything a Yup'ik person did.

Elders: Teachers of Tradition

An Alaska Native elder (tegganeq) is a respected person who has lived a long, healthy life and has a lot of cultural knowledge. Elders share their wisdom with the community and family. Traditionally, they taught younger generations through storytelling. A naucaqun is a lesson or reminder from an elder's experience.

The word tegganeq comes from a Yup'ik word meaning "to be hard" or "to be tough." Yup'ik discipline is based on respecting children. Today, elders are often invited to share their knowledge at conferences and in schools. Some universities even have "elders-in-residence" programs where elders help teach and develop courses.

Yup'ik Society

Family and Community

Yup'ik family groups included parents, children, and grandparents. Relatives from both the mother's and father's sides were equally important. Marriages were often arranged by parents.

In winter, Yup'ik people lived in larger villages to do group activities. Villages had sod houses (ena) for women and girls, and one or more qasgiq for men and boys. There were also warehouses for storage.

Leaders in the Village

In the past, successful hunters who could provide food and skins were seen as leaders. They were called Nukalpiaq, meaning "man in his prime" or "successful hunter and good provider." A nukalpiaq was very important in village life. People would ask for his advice on important matters, especially about ceremonies. He also helped orphans and widows.

However, a nukalpiaq was not like the umialik (whaling captain) of the northern Iñupiaq people. The umialik could collect and share the village's extra resources.

Homes and Living Spaces

Traditionally, Yup'ik people lived in semi-underground houses during winter. Men lived together in a large communal house called a qasgiq, while women and children lived in smaller sod houses called ena. Even though they lived separately, men and women interacted a lot. Sometimes, the qasgiq and ena were connected by a tunnel. Both types of houses were also used as schools and workshops for young boys and girls.

The Ena was a smaller sod house where women and children lived. Two to five women and their children might share an ena. Women were responsible for raising children until boys were old enough to join the men in the qasgiq. Girls learned skills like skin sewing and food preparation in the ena.

The Qasgiq was a larger communal sod house used from November to March. All adult men and boys aged seven and older lived there. Women and girls would bring meals to the men in the qasgiq.

The qasgiq was a school and workshop for young boys. They learned how to make masks, tools, and kayaks. It was also where they learned hunting and fishing skills. Sometimes, men would create a firebath in the qasgiq for cleansing. So, the qasgiq was a home, a bathhouse, and a workshop. It was also the main place for ceremonies and spiritual activities.

It's important to know that Yup'ik people did not live in igloos or snow houses. The word iglu means "house" in the Iñupiaq language, which is similar to the Yup'ik word ngel'u for a "beaver lodge."

Yup'ik Regional Groups

Yup'ik societies were divided into different groups based on their land, how they spoke, their clothing, and their ceremonies. These groups were connected by family ties. Some of these groups included:

- Unalirmiut: Lived in the Norton Sound area.

- Pastulirmiut: Lived near the mouth of the Yukon River.

- Kuigpagmiut: Lived along the Lower Yukon River.

- Marayarmiut: Lived in the Scammon Bay area.

- Askinarmiut: Lived around Hooper Bay and Chevak.

- Qaluyaarmiut: Lived on Nelson Island.

- Akulmiut: Lived on the tundra north of the Kuskokwim River.

- Caninermiut: Lived along the lower Bering Sea coast.

- Nunivaarmiut: Lived on Nunivak Island.

- Kusquqvagmiut: Lived along the Lower and middle Kuskokwim River.

- Tuyuryarmiut: Lived in the Togiak River area.

- Aglurmiut: Lived in the Bristol Bay area.

The Yup'ik people were semi-nomadic, meaning they moved seasonally to find food. However, because there was plenty of fish and game in their areas, they could live a more settled life than some other northern groups. They usually had enough resources in their own territory, but sometimes they would travel and trade with other regions if needed.

Yup'ik Economy and Daily Life

Hunting, Fishing, and Gathering

The Yup'ik homeland is a flat tundra and wetlands area, covering about one-third of Alaska. In the past, Yup'ik people were hunter-fisher-gatherers. They moved with the seasons to harvest sea and land animals, fish, birds, and berries.

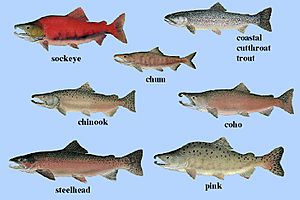

Today, the Yup'ik economy is a mix of traditional hunting and fishing and modern jobs. They still rely on wild resources for food. The coastal areas are especially rich in salmon, which is a very important food source.

| Resource | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| King salmon catching | ||||||||||||

| Red salmon catching | ||||||||||||

| Silver salmon catching | ||||||||||||

| Dolly Varden catching | ||||||||||||

| Whitefish catching | ||||||||||||

| Smelt catching | ||||||||||||

| Pike catching | ||||||||||||

| Other freshwater fish catching | ||||||||||||

| Moose hunting | ||||||||||||

| Caribou hunting | ||||||||||||

| Brown bear hunting | ||||||||||||

| Harbor seal hunting | ||||||||||||

| Bearded & Ringed seal hunting | ||||||||||||

| Sea lion hunting | ||||||||||||

| Porcupine hunting | ||||||||||||

| Hare & Rabbit hunting | ||||||||||||

| Beaver trapping | ||||||||||||

| River otter trapping | ||||||||||||

| Red fox trapping | ||||||||||||

| Parky squirrel trapping | ||||||||||||

| Other furbearers trapping | ||||||||||||

| Ducks & Geese hunting | ||||||||||||

| Ptarmigan hunting | ||||||||||||

| Bird eggs gathering | ||||||||||||

| Clams & Mussels gathering | ||||||||||||

| Berry picking | ||||||||||||

| Basket grass gathering |

How Yup'ik People Travel

Traditionally, Yup'ik people traveled by dog sleds on land and kayaks on water. They used small, closed kayaks and larger, open boats called umiaks for hunting and fishing in the Bering Sea. Kayaks were used more often.

Today, snowmobiles are very important for winter travel. Some areas even have ice roads for vehicles on the Kuskokwim River.

The kayak (qayaq) is a small, narrow boat covered with animal skin. It was first used by people speaking Eskimo–Aleut languages. Yup'ik people used kayaks for seal hunting, fishing, and getting around. A kayak was a hunter's most prized possession and a symbol of manhood. They are fast, easy to steer, good in the water, light, and strong. Kayaks are made from driftwood and covered with sea mammal skin, sewn with sinew.

Kayak stanchions (ayapervik) are pieces on the kayak's cockpit that help a person get in and out without falling. All kayaks had them. Some even had carved faces, like a smiling man and a frowning woman.

The umiak (angyaq) is a larger, open boat also covered with animal skin.

Dog sleds (ikamraq) were an old and common way to travel for Northern Indigenous peoples. However, some Athabaskan groups learned this from their Yup'ik or Iñupiat neighbors. Other Athabaskan groups used to pull their sleds by hand, only using dogs for hunting or carrying packs.

Yup'ik Culture and Traditions

The Yupiit Piciryarait Cultural Center in Bethel helps promote and preserve Yup'ik traditions. It supports traditional and modern Alaska Native art, including crafts, performances, education, and the Yup'ik language.

Language and Learning

The Yup'ik Language

The Yup'ik language is one of the main Yupik languages. It is spoken by the largest number of Native people in Alaska. Yup'ik is a language where you add many endings to words to change their meaning. It has words for singular, plural, and dual (for two things). It does not have grammatical gender or articles like "a" or "the."

The way Yup'ik is written today was developed in the 1960s by Yup'ik elders and language experts at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. In 2007, about 10,400 people out of 25,000 spoke Yup'ik, but the language is considered threatened.

The Yup'ik language has five main dialects, including the extinct Egegik dialect and living dialects like Norton Sound, General Central Yup'ik, Hooper Bay-Chevak, and Nunivak Cup'ig. The Nunivak Island dialect is quite different from the mainland Yup'ik dialects.

| Yup'ik groups | Population | Speakers | Nonspeakers |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Central Yup'ik | 13,702 | 9,622 | 9,080 |

| Unaliq-Pastuliq | 752 | 508 | 244 |

| Hooper Bay-Chevak | 1,037 | 959 | 78 |

| Nunivak | 153 | 92 | 61 |

Yup'ik Education

Before Europeans arrived, Yup'ik knowledge was passed down through spoken stories and traditions, not writing. Children learned about hunting, culture, and social rules through stories, games, and by watching adults.

Early schools in Alaska were often run by churches. Some, like the Russian Orthodox missions, allowed Native languages. However, in the late 1800s, a missionary named Sheldon Jackson started a rule that banned Native languages in mission schools. This rule became widespread by 1910. For many years, children in Alaskan schools were punished for speaking their Native languages.

Things changed with the Bilingual Education Act in 1968. By 1973, 17 Yup'ik villages had bilingual programs in their elementary schools. In recent years, Yup'ik educators have connected more, and young people use the Internet to share their culture. They create a "Yup'ik Worldwide Web" using sites like Facebook and YouTube.

Many Native people in Alaska today are bilingual, speaking English and their own language. All village schools are funded by the state of Alaska. Several school districts in the Yup'ik area offer bilingual education in English and Yup'ik (or Cup'ig).

Yup'ik Stories and Literature

Yup'ik oral storytelling stories are usually split into two types:

- Traditional Legends (qulirat): These are old Yup'ik legends or myths passed down through generations. They often include supernatural elements and are told for fun and learning.

- Historical Narratives (qanemcit): These are personal or historical stories that might have come from a specific person, even if that person is now forgotten.

Yup'ik oral stories were a big part of their society. Young girls often tell "storyknifing" (yaaruilta) stories. They draw pictures in mud or snow with a special knife called a story knife (yaaruin). These knives can be made of wood, ivory, or bone. In Yup'ik storytelling, listeners can find their own meaning in the same story.

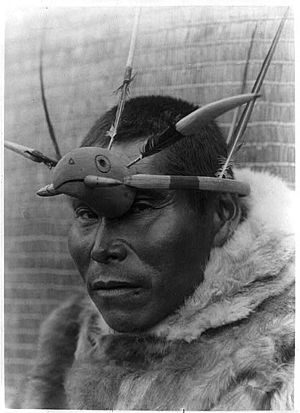

Yup'ik Art

Yup'ik people traditionally decorated most of their tools. One of their most famous art forms is Yup'ik masks. They often made masks for ceremonies, but these masks were usually destroyed after use. Masks were believed to bring good luck for hunting. Other popular art forms include Yup'ik clothing and Yup'ik dolls.

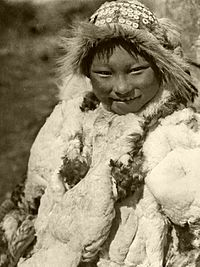

Yup'ik Clothing

The traditional clothing of the Yup'ik and other Northern Indigenous peoples was very effective for cold weather. Yup'ik clothing was usually loose-fitting. Yup'ik women were skilled at sewing skins. They made clothes and footwear from animal skins, especially fur from marine and land mammals, and sometimes birds or fish. They used needles made from animal bones or walrus ivory, and threads made from sinew. The ulu, a special knife, was used to prepare and cut skins.

Most clothing was made from caribou and sealskin. The English words kuspuk (a parka cover) and mukluk (a skin boot) come from Yup'ik words. After Russian fur traders arrived, Yup'ik people were forced to sell many of their furs and use other materials for clothing. Today, many Yup'ik people wear Western-style clothes, but they still make traditional items like mittens and mukluks.

Yup'ik Masks

Yup'ik masks (kegginaquq and nepcetaq) are very expressive ritual masks. They are known for their creativity and are usually made of wood and painted with a few colors. Both men and women carved masks, but mostly men. Masks were often used in ceremonies and then traditionally destroyed. After Christian missionaries arrived in the late 1800s, masked dancing was stopped in many Yup'ik villages.

The National Museum of the American Indian has photographs of Yup'ik ceremonial masks collected in the early 1900s.

Music and Dance

Yup'ik dancing (yuraq) is a traditional form of dancing usually done to Yup'ik songs. Round drums covered with seal stomach and played with wooden sticks provide the rhythm. Both men and women create and perform the dances and sing along. Men usually kneel in front, and women stand behind them. The drummers are at the very back. Dancers use dance fans (called finger masks or maskettes, tegumiak) to make their arm movements more expressive.

Dancing is very important for the social and spiritual life of the Yup'ik community. The Yup'ik people have started practicing their songs and dances again, as they see them as a form of prayer. Traditional dancing in the qasgiq was a community activity. Masks were a central part of these ceremonial dances. There are dances for fun, social gatherings, trading goods, and giving thanks.

The Yuraq is a general term for Yup'ik/Cup'ik dances. Some dances are about animal behavior and hunting, or they might playfully tease people. An "inherited dance" is called Yurapik or Yurapiaq, meaning "real dance." Christian missionaries banned these dances in the late 1800s. However, the Cama-i dance festival, which started in the mid-1980s, brought dancers from different villages together to share their music and dances. Today, many groups perform Yup'ik dances in Alaska.

Yup'ik Toys and Games

An Eskimo yo-yo is a traditional toy with two balls. It's played by Eskimo-speaking Alaska Natives like the Inupiat, Siberian Yupik, and Yup'ik. It looks like fur-covered bolas and a yo-yo. You swing two sealskin balls on caribou sinew strings in opposite directions with one hand. It's a popular toy in Alaska.

Yup'ik Dolls

Yup'ik dolls (yugaq) wear traditional clothing that protected people from the cold. They are often made from natural materials found through gathering food. Play dolls were made from driftwood, bone, or walrus ivory. Some human figures were used by shamans. Dolls also played a role in helping children transition to adulthood in Yup'ik shamanism.

Yup'ik Cuisine

Yup'ik cuisine relies on traditional foods from hunting, fishing, and berry gathering. The Yup'ik region has many waterfowl, fish, and sea and land mammals. Yup'ik people settled in places where water stayed ice-free in winter, where animals like walruses and seals were close to shore, and where there were good fishing streams or bird colonies. If a place had a lot of game, Yup'ik people would settle there, even if it wasn't the easiest place to live.

Coastal communities eat more sea mammals (seals, walruses, beluga whales) and many kinds of fish (Pacific salmon, herring, halibut). Inland communities eat more Pacific salmon, freshwater whitefish, land mammals (moose, caribou), migratory birds, bird eggs, berries, and roots. Today, about half of the food comes from traditional activities, and the other half is bought from stores.

Traditional Yup'ik delicacies include akutaq (Eskimo ice cream) and tepa (stinkheads).

An elevated cache (qulvarvik) is a safe place to store food outdoors, keeping it safe from animals. These raised structures can be made of logs or planks. They are thought to have become common in the 1870s, possibly introduced by early traders or missionaries.

Fish as a Main Food Source

Fish as food, especially Pacific salmon, is a primary food for the Yup'ik. The Yup'ik word for both food and fish (and salmon) is neqa. For salmon, they also say neqpik or neqpiaq, which means "real food." In contrast, the main food for the Iñupiaq people is whale and caribou meat.

Traditional diets in Alaska provide a lot of healthy fats, like omega-3 fatty acids.

Tepas, also called "stinkheads," are fermented fish heads, usually from king or silver salmon. To make them, fish heads and guts are placed in a wooden barrel, covered, and buried for about a week. In modern times, plastic bags were sometimes used, but this increased the risk of a dangerous illness called botulism. So, Yup'ik people have gone back to fermenting fish heads directly in the ground.

Mammals as Food

Muktuk (mangtak) is a traditional meal of frozen raw beluga whale skin with its attached fat (blubber).

Plants as Food

The tundra provides many berries for making jams, jellies, and a special Yup'ik treat called akutaq or "Eskimo ice cream."

Mousefood (ugnarat neqait) refers to the roots of various tundra plants that are stored by small rodents called voles in their burrows.

Yup'ik Ceremonies

Important Yup'ik ceremonies include:

- Nakaciuq (Bladder Festival)

- Elriq (Festival of the Dead)

- Kevgiq (Messenger Feast)

- Petugtaq (requesting certain items)

- Keleq (invitation)

Yup'ik Religion

Shamanism

Historically, Yup'ik traditional religious practices were a form of shamanism based on animism. This means they believed that spirits lived in all things. The shaman (angalkuq), also called a medicine man or woman, was a central figure. The shaman connected the human and spirit worlds through music, dance, and masks. Shamans were responsible for performing ancient prayers for the survival of the people. A powerful shaman was called a angarvak.

Yup'ik shamans guided the creation of masks and composed dances and music for winter ceremonies. The masks often showed spirits the shaman saw in visions. Shaman masks (nepcetaq) were believed to be powerful and represented the shaman's helping spirits (tuunraq). Shamans would wear masks of animals like seals, moose, wolves, and eagles, accompanied by drums and music.

Yup'ik folklore also includes many legendary animals, monsters, and half-human creatures, such as amikuk (a sea monster like an octopus) and tengmiarpak (a giant bird, like a thunderbird). There are also stories of little people and underground dwellers.

Christianity

Yup'ik people in western and southwestern Alaska have a long history with Christianity, influenced by Russian Orthodox, Catholic, and Moravian missionaries. The arrival of missionaries greatly changed life along the Bering Sea coast.

The first Native Americans to become Russian Orthodox were the Aleuts in the mid-1700s. Saint Jacob Netsvetov, a Russian-Alaskan creole and the first Alaska Native Orthodox priest, worked among the Yup'ik. He created an alphabet and translated church materials and parts of the Bible into Yup'ik.

The Moravian Church established a mission in Bethel in 1885. Missionaries like John Henry Kilbuck used the Yup'ik language in their church and helped develop a writing system for it.

The Jesuits (a Catholic religious group) also established missions, moving to Akulurak at the mouth of the Yukon River in 1889. A Spanish Jesuit named Segundo Llorente spent 40 years as a missionary among the Yup'ik.

During Christmas, Yup'ik people often give gifts to remember those who have passed away.

Modern Tribal Groups

Many Yup'ik communities are recognized as Native tribal entities by the United States government.

The Alaska Native Regional Corporations for the Yup'ik were created in 1971 under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA). These corporations manage land and resources for Native people.

| Community | Native Tribal Entity | Native Village Corporation | Native Regional Corporation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Akiachak (Akiacuaq) | Akiachak Native Community | Akiachak Limited | Calista Corporation |

| Akiak (Akiaq) | Akiak Native Community | Kokarmiut Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Alakanuk (Alarneq) | Village of Alakanuk | Alakanuk Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Aleknagik (Alaqnaqiq) | Native Village of Aleknagik | Aleknagik Natives Limited | Bristol Bay Native Corporation |

| Andreafsky (today: St. Mary's) | Yupiit of Andreafski | Nerklikmute Native Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Aniak (Anyaraq) | Village of Aniak | Kuskokwim Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Atmautluak (Atmaulluaq) | Village of Atmautluak | Atmauthluak Limited | Calista Corporation |

| Bethel (Mamterilleq) | Orutsararmuit Native Village (aka Bethel) | Bethel Native Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Bill Moores Slough (Konogkelyokamiut) | ? | Kongnigkilnomuit Yuita Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Chefornak (Cevv'arneq) | Village of Chefornak | Chefarnrmute Inc. | Calista Corporation |

| Chevak (Cev'aq) | Chevak Native Village | Chevak Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Chuathbaluk (Curarpalek) | Native Village of Chuathbaluk (Russian Mission, Kuskokwim) | Kuskokwim Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Chuloonawick (? culunivik) | Chuloonawick Native Village | Chuloonawick Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Clarks Point (Saguyaq) | Village of Clarks Point | Saguyak Inc. | Bristol Bay Native Corporation |

| Crooked Creek (Qipcarpak) | Village of Crooked Creek | Kuskokwim Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Dillingham (Curyung) | Curyung Tribal Council (formerly the Native Village of Dillingham) | Choggiung Limited | Bristol Bay Native Corporation |

| Eek (Ekvicuaq) | EekNative Village of Eek | Iqfijouq Co | Calista Corporation |

| Egegik (Igyagiiq) | Egegik Village | Becharof Corporation | Bristol Bay Native Corporation |

| Ekuk | Native Village of Ekuk | Ekuk Native Limited | Bristol Bay Native Corporation |

| Ekwok (Iquaq) | Ekwok Village | Ekwok Natives Limited | Bristol Bay Native Corporation |

| Elim (Neviarcaurluq) | Native Village of Elim | Elim Native Corporation | Bering Straits Native Corp. |

| Emmonak (Imangaq) | Emmonak Village | Emmonak Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Golovin (Cingik) | Chinik Eskimo Community (Golovin) | Golovin Native Corporation | Cook Inlet Region, Incorporated |

| Goodnews Bay (Mamterat) | Native Village of Goodnews Bay | Kiutsarak Inc. | Calista Corporation |

| Hamilton (Nunapigglugaq) | Native Village of Hamilton | Nunapiglluraq Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Holy Cross (Ingirraller) | Holy Cross Village | Deloycheet Inc. | Doyon, Limited |

| Hooper Bay (Naparyaarmiut) | Native Village of Hooper Bay | Sea Lion Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Igiugig (Igyaraq) | Igiugig Village | Igiugig Native Corporation | Bristol Bay Native Corporation |

| Iliamna (Illiamna) | Village of Iliamna | Iliamna Native Corporation | Bristol Bay Native Corporation |

| Kasigluk (Kassigluq) | Kaskigluk Traditional Elders Council (formerly the Native Village of Kasigluk) | Kasigluk Inc. | Calista Corporation |

| Kipnuk (Qipnek) | Native Village of Kipnuk | Kugkaktilk Limited | Calista Corporation |

| Kokhanok (Qarr'unaq) | Kokhanok Village | Kokhanok Native Corporation | Alaska Peninsula Corporation |

| Koliganek (Qalirneq) | New Koliganek Village Council (formerly the Koliganek Village) | Koliganek Natives Limited | Bristol Bay Native Corporation |

| Kongiganak (Kangirnaq) | Native Village of Kongiganak | Qemirtalek Coast Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Kotlik (Qerrulliik) | Village of Kotlik | Kotlik Yupik Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Kwethluk (Kuiggluk) | Organized Village of Kwethluk | Kwethluk Inc. | Calista Corporation |

| Kwigillingok (Kuigilnguq) | Native Village of Kwigillingok | Kwik Inc. | Calista Corporation |

| Levelock (Liivlek) | Levelock Village | Levelock Natives Limited | Bristol Bay Native Corporation |

| Lower Kalskag (Qalqaq) | Village of Lower Kalskag | Kuskokwim Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| McGrath | McGrath Native Village | MTNT Limited | Doyon, Limited |

| Manokotak (Manuquutaq) | Manokotak Village | Manokotak Natives Limited | Bristol Bay Native Corporation |

| Marshall (Masserculleq) | Native Village of Marshall (aka Fortuna Ledge) | Maserculig Inc. | Calista Corporation |

| Mekoryuk (Mikuryar) | Native Village of Mekoryuk | Nima Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Mountain Village (Asaacaryaraq) | Asa'carsarmiut Tribe (formerly the Native Village of Mountain Village) | Azachorok Inc. | Calista Corporation |

| Nagamut | ? | Nagamut Limited | Calista Corporation |

| Naknek (Nakniq) | Naknek Native Village | Paug-Vik Inc. Limited | Bristol Bay Native Corporation |

| Napaimute (Napamiut) | Native Village of Napaimute | Kuskokwim Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Napakiak (Naparyarraq) | Native Village of Napakiak | Napakiak Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Napaskiak (Napaskiaq) | Native Village of Napaskiak | Napaskiak Inc. | Calista Corporation |

| Newhalen (Nuuriileng) | Newhalen Village | Newhalen Native Corporation | Alaska Peninsula Corporation |

| New Stuyahok (Cetuyaraq) | New Stuyahok Village | Stuyahok Limited | Bristol Bay Native Corporation |

| Newtok (Niugtaq) | Newtok Village | Newtok Inc. | Calista Corporation |

| Nightmute (Negtemiut) | Native Village of Nightmute | NGTA Inc. | Calista Corporation |

| Nunam Iqua (Nunam Iqua) | Native Village of Nunam Iqua (formerly the Native Village of Sheldon's Point) | Swan Lake Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Nunapitchuk (Nunapicuar) | Native Village of Nunapitchuk | Nunapitchuk Limited | Calista Corporation |

| Ohagamiut (Urr'agmiut) | Village of Ohogamiut | Ohog Inc. | Calista Corporation |

| Oscarville (Kuiggayagaq) | Oscarville Traditional Village | Oscarville Native Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Paimiut | Native Village of Paimiut | Paimiut Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Pilot Station (Tuutalgaq) | Pilot Station Traditional Village | Pilot Station Native Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Pitkas Point (Negeqliim Painga) | Native Village of Pitka's Point | Pitkas Point Native Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Platinum (Arviiq) | Platinum Traditional Village | Arvig Inc. | Calista Corporation |

| Portage Creek | Portage Creek Village (aka Ohgsenakale) | Ohgsenskale Corporation | Bristol Bay Native Corporation |

| Quinhagak (Kuinerraq) | Native Village of Kwinhagak (aka Quinhagak) | Qanirtuuq Inc. | Calista Corporation |

| Russian Mission (Iqugmiut) | Iqurmiut Traditional Council (formerly the Native Village of Russian Mission) | Russian Mission Native Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| St. Marys (Negeqliq) | Algaaciq Native Village (St. Mary's) | St. Marys Native Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| St. Michael (Taciq) | Native Village of Saint Michael | St. Michael Native Corporation | Bering Straits Native Corp. |

| Scammon Bay (Marayaarmiut) | Native Village of Scammon Bay | Askinuk Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Sleetmute (Cellitemiut) | Village of Sleetmute | Kuskokwim Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| South Naknek (Qinuyang) | South Naknek Village | Quinuyang Limited | Alaska Peninsula Corporation |

| Stebbins (Tapraq) | Stebbins Community Association | Stebbins Native Corporation | Bering Straits Native Corp. |

| Stony River | Village of Stony River | Kuskokwim Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Togiak (Tuyuryaq) | Traditional Village of Togiak | Togiak Natives Limited | Bristol Bay Native Corporation |

| Toksook Bay (Nunakauyaq) | Nunakauyarmiut Tribe (formerly the Native Village of Toksook Bay) | Nunakauiak Yupik Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Tuluksak (Tuulkessaaq) | Tuluksak Native Community | Tulkisarmute Inc. | Calista Corporation |

| Tuntutuliak (Tuntutuliaq) | Native Village of Tuntutuliak | Tuntutuliak Land Limited | Calista Corporation |

| Tununak (Tununeq) | Native Village of Tununak | Tununrmiut Rinit Corporation | Calista Corporation |

| Twin Hills (Ingricuar) | Twin Hills Village | Twin Hills Native Corporation | Bristol Bay Native Corporation |

| Umkumiute | Umkumiute Native Village | Umkumiute Limited | Calista Corporation |

| Upper Kalskag (Qalqaq) | Village of Kalskag | Kuskokwim Corporation | Calista Corporation |

Notable Yup'ik People

- Uyaquq (c. 1860–1924): A Moravian helper, writer, translator, and inventor of a Yup'ik writing system.

- Oscar Kawagley (born 1934): A Yup'ik anthropologist, teacher, and actor.

- Marie Meade: A Yugtun language expert.

- Rita Pitka Blumenstein (1936–2021): The first certified traditional doctor in Alaska.

- Todd Palin (born 1964): An American with English and Yup'ik ancestry, known as an oil field operator, commercial fisherman, and snowmobile racer. He was the First Gentleman of Alaska from 2006–2009.

- Ramy Brooks (born 1968): A dog musher with Yup'ik and Athabaskan heritage.

- Callan Chythlook-Sifsof (born 1989): A Yup'ik-Inupiaq snowboarder who competed in the Olympics. She was the first Yup'ik Eskimo on the U.S. National Snowboard Team.

- Emily Johnson (born 1976): An American dancer, writer, and choreographer of Yup'ik descent.

- Lyman Hoffman: A Democratic member of the Alaska Senate.

- Mary Sattler (born 1973): A Democratic politician in Alaska.

- Walt Monegan (born 1951): The former Police Chief of Anchorage.

- Valerie Nurr'araaluk Davidson: A former Lieutenant Governor of Alaska.

- Byron Nicholai: A viral musician.

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |