Indo-Aryan migrations facts for kids

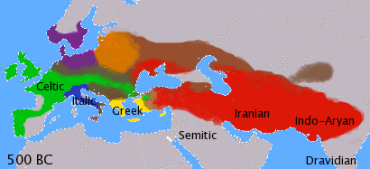

The Indo-Aryan migrations were when groups of people, called Indo-Aryan peoples, moved into the Indian subcontinent. These people spoke Indo-Aryan languages. Today, these languages are common in countries like Bangladesh, Maldives, Nepal, North India, eastern Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.

These migrations from Central Asia are thought to have begun after 2000 BCE. They were a slow spread during the Late Harappan period. This led to a big language shift in northern India. Later, Iranian languages were brought to the Iranian plateau by the Iranians, who were related to the Indo-Aryans.

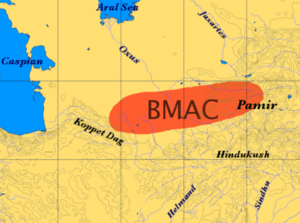

The early culture that led to both Indo-Aryans and Iranians was called Proto-Indo-Iranian. It grew on the Central Asian steppes, north of the Caspian Sea. This started with the Sintashta culture (around 2200-1900 BCE) in what is now Russia and Kazakhstan. It then developed further into the Andronovo culture (2000–1450 BCE).

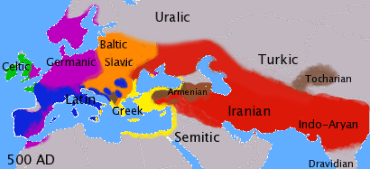

The Indo-Aryans separated from the Indo-Iranians between 2000 BCE and 1600 BCE. They moved south to the Bactria–Margiana culture (BMAC). From this culture, they adopted some unique religious beliefs and practices. From the BMAC, Indo-Aryans moved into northern Syria and, likely in several waves, into the Punjab (northern Pakistan and India). The Iranians might have reached western Iran before 1300 BCE. Both groups brought their Indo-Iranian languages with them.

The idea of Indo-European-speaking people moving was first suggested in the late 1700s. This happened after people noticed similarities between western and Indian languages. Because of these links, it was thought that all these languages came from a single origin. This origin spread through migrations from a homeland.

This language-based idea is supported by studies in archaeology, anthropology, genetics, literature, and ecology. Genetic research shows these migrations are part of a complex story of how different groups formed the Indian population. Literary studies show similarities between Indo-Aryan cultures in different places. Ecological studies suggest that around 2000 BCE, widespread dry weather caused water shortages. This affected both the Eurasian steppes and the Indian subcontinent. It led to the collapse of settled city cultures in central Asia, Afghanistan, Iran, and India. This then caused large migrations, mixing different peoples with the cultures that remained after the cities fell.

The Indo-Aryan migrations began around 2000 to 1600 BCE. This was after the war chariot was invented. These migrations also brought Indo-Aryan languages to the Levant and possibly Inner Asia. This was part of a larger spread of Indo-European languages from their original home, the proto-Indo-European homeland on the Pontic–Caspian steppe. This spread started much earlier, around 5000-4000 BCE.

These Indo-Aryan speakers shared cultural rules and a language, which they called ārya, meaning "noble." Their culture and language spread through a system where powerful people supported others. This allowed other groups to join and adopt this culture. This explains why it had such a strong influence on other cultures it met.

Contents

- Why Do We Think This Happened?

- How the Theory Developed

- Language Clues: How Languages Are Connected

- Archaeology: Migrations from the Steppe Homeland

- Human Studies: Elite Influence and Language Change

- Literary Research: Similarities and Migration Clues

- Ecology

- Indigenous Aryanism

- See also

- Images for kids

Why Do We Think This Happened?

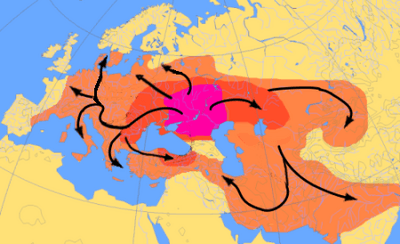

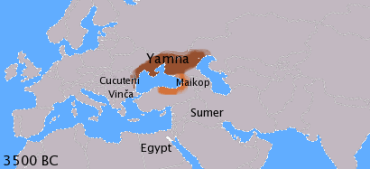

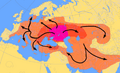

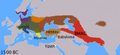

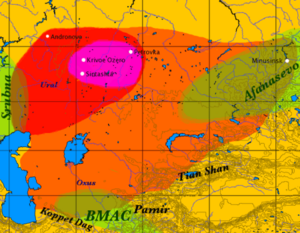

– Center: Steppe cultures

1 (black): Anatolian languages (very old PIE)

2 (black): Afanasievo culture (early PIE)

3 (black) Yamnaya culture spreading (Pontic-Caspian steppe, Danube Valley) (later PIE)

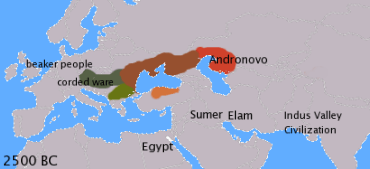

4A (black): Western Corded Ware

4B-C (blue & dark blue): Bell Beaker; adopted by Indo-European speakers

5C (red): Sintashta (early Indo-Iranian)

6 (magenta): Andronovo

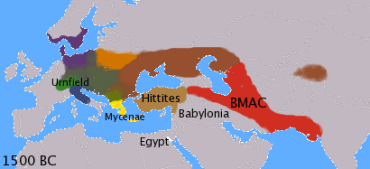

7A (purple): Indo-Aryans (Mittani)

7B (purple): Indo-Aryans (India)

[NN] (dark yellow): early Balto-Slavic

8 (grey): Greek

9 (yellow): Iranians

– [not drawn]: Armenian, spreading from western steppe

The idea of Indo-Aryan migration is part of a bigger picture. This picture helps explain why many modern and ancient languages are similar. It brings together studies from language, archaeology, and human cultures. This helps us understand how Indo-European languages developed and spread through movement and cultural mixing.

Language Clues: How Languages Are Connected

The language part of this theory looks at the links between different Indo-European languages. It tries to rebuild the proto-Indo-European language, which was their common ancestor. This is possible because languages change in predictable ways. Changes in sounds (vowels and consonants) are very important. Grammar and vocabulary also give clues. This method helps us see how languages that seem very different are actually related. Many features of Indo-European languages suggest they did not start in India, but rather in the steppes.

Archaeology: Moving from the Steppe Homeland

Archaeology suggests an "Urheimat" (original home) on the Pontic steppes. This area changed after cattle were brought there around 5200 BCE. This led to a shift from hunting and gathering to herding. It also led to a society with leaders, a system of support, and trade. The oldest core of this culture might be the Samara culture (late 6th and early 5th millennium BCE).

A wider area, called the Kurgan culture by Marija Gimbutas in the 1950s, then developed. This included the Samara culture and the Yamna culture (36th–23rd centuries BCE). The Yamna culture is often seen as the main center of the early Indo-European language. From this area, Indo-European languages spread west, south, and east starting around 4000 BCE. Small groups of men might have carried these languages. They used a system of patronage that allowed other groups to join their culture.

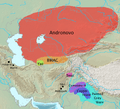

To the east, the Sintashta culture (2200–1900 BCE) appeared, where early Indo-Iranian was spoken. The Andronovo culture (2000–1450 BCE) grew out of Sintashta. It interacted with the Bactria-Margiana culture (2250–1700 BCE). This interaction further shaped the Indo-Iranians. They split into Indo-Aryans and Iranians between 2000 and 1600 BCE. The Indo-Aryans moved to the Levant and South Asia. The move into northern India was not a huge invasion. It might have been small groups of people. Their culture and language spread by similar ways of cultural mixing.

Human Studies: How Languages Change

Indo-European languages likely spread through language shifts. Small groups can change a larger cultural area. A small group of powerful men might have led to a language shift in northern India.

David Anthony, who studied the "Steppe hypothesis," suggests that Indo-European languages did not spread by simple "folk migrations." Instead, they were introduced by important religious and political leaders. Larger groups of people then copied these leaders. He calls this "elite recruitment."

According to Asko Parpola, local leaders joined "small but powerful groups" of Indo-European-speaking migrants. These migrants had an appealing social system, good weapons, and fancy goods that showed their status. Joining these groups was good for local leaders. It made them stronger and gave them more advantages. These new members were further connected through marriages.

Joseph Salmons says that language change happens more easily when communities are "dislocated." This means when the ruling group changes. He also says this change is helped by "systematic changes in community structure." This is when a local community becomes part of a larger social system.

Genetics: Ancient Roots and Gene Flows

The Indo-Aryan migrations are part of a complex genetic puzzle. This puzzle explains where different parts of the Indian population came from. It includes different waves of mixing and language changes. Studies show that people in north and south India share a common female ancestry. Other studies show two main ancestral groups in mainland India. These are the Ancestral North Indians (ANI), who are "genetically close to Middle Easterners, Central Asians, and Europeans." The other group is the Ancestral South Indians (ASI), who are very different from ANI. These two groups mixed in India between 4200 and 1900 years ago (2200 BCE – 100 CE). After this, people started marrying only within their own groups. This might have been due to "social values and norms" during the Gupta Empire.

Moorjani et al. (2013) suggest three ways these groups came together. One is migrations before farming developed (before 8000-9000 years ago). Another is migration of western Asian people with the spread of farming (maybe up to 4600 years ago). The third is migrations of western Eurasians from 3000 to 4000 years ago.

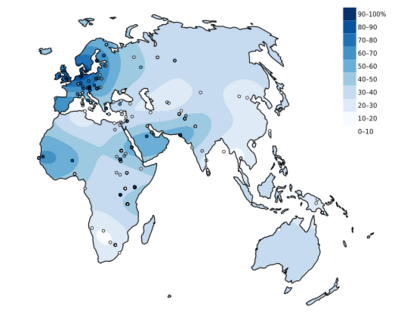

While Reich notes that mixing started when Indo-European languages arrived, Moorjani et al. (2013) say these groups were in India "unmixed" before the Indo-Aryan migrations. Gallego Romero et al. (2011) suggest the ANI came from Iran and the Middle East less than 10,000 years ago. Lazaridis et al. (2016) say ANI is a mix of "early farmers of western Iran" and "people of the Bronze Age Eurasian steppe." Other studies also show signs of later influences of female and male genetic material related to ANI and possibly Indo-Europeans. Some have looked at how lactose intolerance is passed down. They specifically looked at a gene change (-13910T) found in Europe and Central Asia, which is also present across South Asia.

Literary Clues: Similarities and Migration Stories

The oldest known Indo-Iranian words are from the mid-2nd millennium BCE. They are found as borrowed words in Hurrian treaties of the Mitanni kingdom in northern Syria. These words include names of Indo-Aryan gods.

The religious practices in the Rigveda and the Avesta (a main religious text of Zoroastrianism) are similar. Some mentions of the Sarasvati River in the Rigveda refer to the Ghaggar-Hakra River. The Afghan river Haraxvaiti/Harauvati Helmand is sometimes said to be the location of the early Rigvedic river. The Rigveda does not directly mention a homeland outside India or a migration. However, later Vedic and Puranic texts do show movement into the Gangetic plains. Some scholars point to a verse in the Baudhayana Shrauta Sutra (18.44:397.9) as clear proof of a migration:

Then, there is the following direct statement contained in (the admittedly much later) BSS [Baudhāyana Śrauta Sūtra] 18.44:397.9 sqq which has once again been overlooked, not having been translated yet: "Ayu went eastwards. His (people) are the Kuru Panchala and the Kasi-Videha. This is the Ayava (migration). (His other people) stayed at home. His people are the Gandhari, Parsu and Aratta. This is the Amavasava (group)" (Witzel 1989: 235).

Environmental Studies: Drought and Migrations

Changes in climate and dry periods might have caused both the first spread of Indo-European speakers and their move from the steppes into central Asia and India.

Around 4200–4100 BCE, the climate changed, bringing colder winters to Europe. Steppe herders, who spoke early Proto-Indo-European, spread into the lower Danube valley around 4200–4000 BCE. They either caused or took advantage of the collapse of Old Europe.

The Yamna culture adapted to a climate change between 3500 and 3000 BCE. The steppes became drier and cooler. Herds needed to be moved often to find enough food. Using wagons and riding horses made this possible. This led to "a new, more mobile form of pastoralism."

In the 3rd millennium BCE, widespread dry conditions led to water shortages. This caused environmental changes in both the Eurasian steppes and the Indian subcontinent. On the steppes, more humid conditions changed the plants, leading to "higher mobility and transition to nomadic cattle breeding." Water shortages also greatly affected the Indian subcontinent. This "caused the collapse of settled city cultures in south central Asia, Afghanistan, Iran, and India, and triggered large-scale migrations." This resulted in migrating peoples mixing with the cultures that remained after the cities fell.

How the Theory Developed

Similarities in Old Languages

In the 1500s, Europeans visiting India noticed similarities between Indian and European languages. As early as 1653, Van Boxhorn suggested a common early language for Germanic, Romance, Greek, Baltic, Slavic, Celtic, and Iranian languages.

In 1767, Gaston-Laurent Coeurdoux, a French Jesuit in India, clearly showed the links between Sanskrit and European languages.

In 1786, William Jones, a judge and language expert in Calcutta, studied Sanskrit. He suggested a common early language for Sanskrit, Persian, Greek, Latin, Gothic, and Celtic languages. He noted:

The Sanskrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and in the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists: there is a similar reason, though not quite so forcible, for supposing that both the Gothic and the Celtic, though blended with a very different idiom, had the same origin with the Sanskrit; and the old Persian might be added to the same family, if this were the place for discussing any question concerning the antiquities of Persia.

Jones concluded that all these languages came from the same source.

The Original Homeland

Scholars believe the original homeland was in Central Asia or Western Asia. This means Sanskrit must have reached India by language transfer from west to east. In the 1800s, the language of the Rigveda was the oldest Indo-European language known. This led scholars like Friedrich Schlegel to think the proto-Indo-European homeland was in India. They thought other dialects spread west from there.

But in the 1900s, older Indo-European writings were found (like Anatolian and Mycenaean Greek). This meant Vedic Sanskrit was no longer seen as the oldest Indo-European language.

The "Aryan Race" Idea

In the 1850s, Max Müller suggested two Aryan "races." One was western, and one was eastern. They both migrated from the Caucasus into Europe and India. Müller saw the western group as more important. He thought the "eastern branch of the Aryan race was more powerful than the local eastern natives, who were easy to conquer."

Herbert Hope Risley built on Müller's idea. He thought the caste system was a leftover from Indo-Aryans ruling the native Dravidians. He believed physical differences could be seen between castes. Thomas Trautmann explains that Risley "found a direct relation between the proportion of Aryan blood and the nasal index, along a gradient from the highest castes to the lowest. This assimilation of caste to race proved very influential."

Müller's work helped grow interest in "Aryan" culture. This often put Indo-European traditions against Semitic religions. Müller was "deeply saddened" that his ideas were later used in racist ways. This was not his goal. For Müller, finding a common Indian and European ancestry was a strong argument against racism. He said that someone who talks about "Aryan race, Aryan blood, Aryan eyes and hair" is as wrong as a linguist who talks about a "dictionary with a certain head shape." He also said that "the blackest Hindus represent an earlier stage of Aryan speech and thought than the fairest Scandinavians." Later, Max Müller made sure to use the term "Aryan" only for language.

"Aryan Invasion" Idea

In the 1920s, sites like Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, and Lothal of the Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC) were found. This showed that northern India already had an advanced culture when the Indo-Aryans arrived. The theory changed. It was no longer about advanced Aryans moving to a primitive people. Instead, it was about nomadic people moving into an advanced city civilization. This was compared to Germanic migrations during the Fall of the Western Roman Empire.

For a short time, this was seen as a hostile invasion. The decline of the Indus Valley Civilisation happened around the same time as the Indo-Aryan migrations. This seemed to support the invasion idea. Mortimer Wheeler, an archaeologist, suggested this in the mid-1900s. He saw many unburied bodies in Mohenjo-daro as victims of war. He famously said that the god "Indra stands accused" of destroying the civilization.

This idea was later dropped because no evidence of wars was found. The skeletons were from quick burials, not massacres. Wheeler himself later softened his view. He said, "This is a possibility, but it can't be proven, and it may not be correct." He also noted that the unburied bodies might show an event at the end of human life in Mohenjo-Daro. But the decay of Mohenjo-Daro was due to other problems like salt in the soil.

Still, even though the "invasion" idea was disproven, critics of the Indo-Aryan Migration theory still call it the "Aryan Invasion Theory." They present it as a racist and colonial idea:

The theory of an immigration of IA speaking Arya ("Aryan invasion") is simply seen as a means of British policy to justify their own intrusion into India and their subsequent colonial rule: in both cases, a "white race" was seen as subduing the local darker colored population.

Aryan Migration

In the late 1900s, ideas became more detailed as more information was found. Migration and acculturation (cultural mixing) were seen as the ways Indo-Aryans and their language spread into northwest India around 1500 BCE. The word "invasion" is now only used by those who oppose the Indo-Aryan Migration theory. Michael Witzel explains:

...it has been supplanted by much more sophisticated models over the past few decades [...] philologists first, and archaeologists somewhat later, noticed certain inconsistencies in the older theory and tried to find new explanations, a new version of the immigration theories.

This new approach fit with new ideas about how languages spread in general. Examples include the migration of the Greeks into Greece (between 2100 and 1600 BCE) and their adoption of a writing system, Linear B. Also, the spread of Indo-European languages in Western Europe (in stages between 2200 and 1300 BCE).

Language Clues: How Languages Are Connected

Language studies trace the links between different Indo-European languages. They try to rebuild the early Indo-European language. Many language clues suggest that Indo-Aryan languages came into the Indian subcontinent sometime in the 2nd millennium BCE. The language of the Rigveda, the oldest part of Vedic Sanskrit, is thought to be from about 1500–1200 BCE.

Comparing Languages

Languages can be linked because they change in regular ways. Changes in sounds (vowels and consonants) are especially important. Grammar and vocabulary also matter. This method helps us see big similarities between languages that might seem very different at first.

Linguists use the comparative method to study how languages developed. They compare features of two or more languages that came from a common ancestor. This is different from "internal reconstruction," which looks at how one language changed over time. Usually, both methods are used together. They help rebuild early stages of languages, fill in missing history, and understand how language systems developed. They also help confirm or deny ideas about how languages are related.

The comparative method aims to prove that languages came from a single "proto-language." It does this by comparing lists of similar words. From these, regular sound changes between the languages are found. Then, a series of sound changes can be suggested. This allows the proto-language to be rebuilt. A relationship is considered certain only if a common ancestor can be partly rebuilt. Also, regular sound links must be found, and accidental similarities ruled out.

This method was developed in the 1800s. Key people were Rasmus Rask, Karl Verner, and Jacob Grimm. The first linguist to suggest rebuilt forms from a proto-language was August Schleicher in 1861.

Proto-Indo-European

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the rebuilt common ancestor of the Indo-European languages. August Schleicher's 1861 rebuilding of PIE was the first accepted by modern linguists. More work has gone into rebuilding PIE than any other proto-language. It is by far the best understood. In the 1800s, most language work focused on rebuilding PIE or its daughter languages, like Proto-Germanic. Most of the current methods for rebuilding languages were developed because of this.

PIE must have been spoken as a single language or a group of related dialects before they split. Estimates for when this happened vary greatly, from 7000 BCE to 2000 BCE. Many ideas have been suggested for where the language started and spread. The most popular among linguists is the Kurgan hypothesis. This suggests an origin in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of Eastern Europe in the 5th or 4th millennia BCE. Features of the culture of PIE speakers, called Proto-Indo-Europeans, have also been rebuilt based on shared words in early Indo-European languages.

As mentioned, the idea of PIE was first suggested in the 1700s by Sir William Jones. He noticed similarities between Sanskrit, Ancient Greek, and Latin. By the early 1900s, clear descriptions of PIE were developed that are still accepted today. The biggest developments in the 1900s were finding the Anatolian and Tocharian languages. Also, the acceptance of the "laryngeal theory" was important. The Anatolian languages have also led to a big re-evaluation of ideas about how various shared Indo-European language features developed. And how much these features were present in PIE itself. Links to other language families, like the Uralic languages, have been suggested but are still debated.

PIE is thought to have had a complex system of word structure. This included endings that change words and vowel changes (like in English sing, sang, sung). Nouns and verbs had complex systems for changing their forms.

Why PIE Probably Didn't Start in India

Language Variety

The "linguistic center of gravity" idea says that a language family most likely started where it has the most variety. By this rule, Northern India is not a likely place for the Indo-European homeland. It only has one branch of the family (Indo-Aryan). Central-Eastern Europe, for example, has many branches like Italic, Venetic, Illyrian, Albanian, Germanic, Baltic, Slavic, Thracian, and Greek.

Most main ideas for the PIE homeland place it near the Black Sea.

Dialect Differences

Since the mid-1800s, scholars have known that a simple "family tree" model cannot show all language links. Some features cross language groups. These are better explained by a "wave model," where changes spread out like ripples. This is true for Indo-European languages too. Different features started and spread when Proto-Indo-European was still a group of related dialects. These features sometimes cross sub-families. For example, the plural endings for instrumental, dative, and ablative cases in Germanic and Balto-Slavic languages start with -m-. This is different from the usual -*bh-. For example, Gothic dative plural sunum 'to the sons' and Old Church Slavonic instrumental plural synъ-mi 'with sons'. This is true even though Germanic languages are centum and Balto-Slavic languages are satem.

The strong match between the dialect links of Indo-European languages and their actual locations in their earliest forms makes an Indian origin unlikely. This goes against the Out of India Theory.

Influence from Other Languages

As early as the 1870s, linguists realized that Greek/Latin vowels could not be explained by Sanskrit vowels. So, Greek/Latin must be older. Indo-Iranian and Uralic languages influenced each other. Finno-Ugric languages have Indo-European loan words. A good example is the Finnish word vasara, meaning "hammer," which is related to vajra, the weapon of Indra. Since the Finno-Ugric homeland was in northern Europe, the contact must have happened between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. This fits with the idea of the proto-Indo-European homeland being on the Pontic-Caspian steppes.

Dravidian and other South Asian languages share some grammar and word structure features with Indo-Aryan. These features are not found in other Indo-European languages, even its closest relative, Old Iranian. In terms of sounds, there is the use of retroflexes, which switch with dentals in Indo-Aryan. In terms of word structure, there are the gerunds. And in terms of sentence structure, there is the use of a quotative marker (iti). These are seen as proof of influence from a substratum language.

Some have argued that Dravidian influenced Indic through "shift." This means native Dravidian speakers learned and adopted Indic languages. The presence of Dravidian features in Old Indo-Aryan is explained by this. It suggests that most early Old Indo-Aryan speakers had Dravidian as their first language, which they slowly gave up. Even though new features in Indic could have many internal explanations, early Dravidian influence is the only one that explains all the new features at once. It is a simpler explanation. Also, early Dravidian influence explains several new features in Indic better than any internal explanation.

A pre-Indo-European language substratum in the Indian subcontinent would be a good reason to rule out India as a possible Indo-European homeland. However, some linguists, while accepting the external origin of Aryan languages for other reasons, are still open to seeing the evidence as internal developments. Or as adstratum effects (influence from a neighboring language).

Archaeology: Migrations from the Steppe Homeland

|

||

|

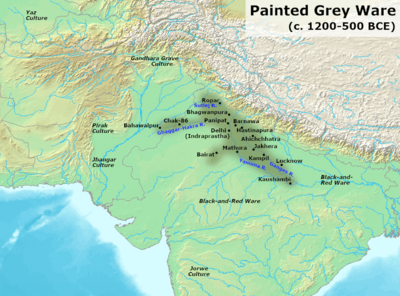

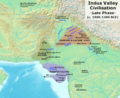

The Sintashta, Andronovo, Bactria-Margiana, and Yaz cultures have been linked to Indo-Iranian migrations in Central Asia. The Gandhara Grave, Cemetery H, Copper Hoard, and Painted Grey Ware cultures are thought to be later cultures in South Asia connected to Indo-Aryan movements. The decline of the Indus Valley Civilisation happened before the Indo-Aryan migrations. But archaeological findings show that culture continued in the area. Along with Dravidian words found in the Rigveda, this suggests interaction between post-Harappan and Indo-Aryan cultures.

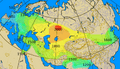

Stages of Migrations

About 6,000 years ago, Indo-Europeans began to spread from their original home in Central Eurasia. This area was between the southern Ural Mountains, the North Caucasus, and the Black Sea. About 4,000 years ago, Indo-European-speaking peoples started to move out of the Eurasian steppes.

Spreading from the "Urheimat"

Scholars believe the middle Volga region, where the Samara culture (late 6th and early 5th millennium BCE) and the Yamna culture were located, was the "Urheimat" (original home) of the Indo-Europeans. This is described by the Kurgan hypothesis. From this "Urheimat," Indo-European languages spread across the Eurasian steppes between about 4500 and 2500 BCE, forming the Yamna culture.

Order of Migrations

David Anthony provides a detailed look at the order of these migrations.

The oldest known Indo-European language is Hittite. It belongs to the Anatolian branch, which is one of the oldest written Indo-European languages. Although the Hittites are from the 2nd millennium BCE, the Anatolian branch seems to be older than Proto-Indo-European. It might have developed from an even older ancestor. If it separated from Proto-Indo-European, it likely did so between 4500 and 3500 BCE.

A migration of early Proto-Indo-European-speaking steppe herders into the lower Danube valley happened around 4200–4000 BCE. This either caused or took advantage of the collapse of Old Europe.

According to Mallory and Adams, migrations southward led to the Maykop culture (about 3500–2500 BCE). Migrations eastward led to the Afanasevo culture (about 3500–2500 BCE), which developed into the Tocharians (about 3700–3300 BCE).

Anthony says that between 3100 and 2800/2600 BCE, a real migration of Proto-Indo-European speakers from the Yamna culture happened towards the west, into the Danube Valley. These migrations likely separated Pre-Italic, Pre-Celtic, and Pre-Germanic from Proto-Indo-European. According to Anthony, this was followed by a move north, which separated Baltic-Slavic around 2800 BCE. Pre-Armenian split off at the same time. Parpola suggests this migration is linked to Indo-European speakers from Europe appearing in Anatolia, and the appearance of Hittite.

The Corded Ware culture in Middle Europe (2900–2450/2350 BCE) has been linked to some Indo-European languages. According to Haak et al. (2015), a huge migration happened from the Eurasian steppes to Central Europe.

This migration is closely linked to the Corded Ware culture.

The Indo-Iranian language and culture appeared in the Sintashta culture (about 2050–1900 BCE), where the chariot was invented. Allentoft et al. (2015) found a close genetic link between people of the Corded Ware culture and Sintashta culture. This "suggests similar genetic sources of the two" and might mean that "the Sintashta comes directly from an eastward migration of Corded Ware peoples."

The Indo-Iranian language and culture further developed in the Andronovo culture (about 2000–1450 BCE). It was influenced by the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (about 2250–1700 BCE). The Indo-Aryans separated from the Iranians sometime around 2000–1600 BCE. After this, Indo-Aryan groups are thought to have moved to the Levant (Mitanni), northern India (Vedic people, about 1500 BCE), and China (Wusun). After that, the Iranians migrated into Iran.

Central Asia: How Indo-Iranians Formed

Indo-Iranian peoples are a group of ethnic groups. They include the Indo-Aryan, Iranian, and Nuristani peoples. These are people who speak Indo-Iranian languages.

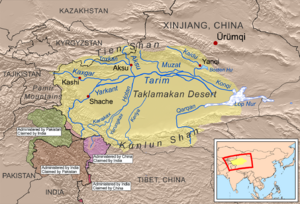

The Proto-Indo-Iranians are usually linked to the Andronovo culture. This culture thrived around 2000–1450 BCE in an area of the Eurasian Steppe. This area borders the Ural River to the west and the Tian Shan to the east. The older Sintashta culture (2200–1900), once part of the Andronovo culture, is now seen separately. But it is considered its predecessor and part of the wider Andronovo group.

The Indo-Aryan migration was part of the Indo-Iranian migrations from the Andronovo culture into Anatolia, Iran, and South Asia.

Sintashta-Petrovka Culture

The Sintashta culture, also known as Sintashta-Petrovka or Sintashta-Arkaim, is a Bronze Age archaeological culture. It was found on the northern Eurasian Steppe, near the borders of Eastern Europe and Central Asia. It dates from 2200–1900 BCE. The Sintashta culture is likely where the Indo-Iranian language group came from.

The Sintashta culture grew from two earlier cultures. Its direct predecessor in the Ural-Tobol steppe was the Poltavka culture. This was a branch of the cattle-herding Yamnaya horizon that moved east between 2800 and 2600 BCE. Many Sintashta towns were built over older Poltovka settlements or near Poltovka cemeteries. Poltovka designs are common on Sintashta pottery. Sintashta material culture also shows influence from the late Abashevo culture. This was a group of Corded Ware settlements north of the Sintashta region, mostly focused on herding. Allentoft et al. (2015) also found a close genetic link between people of the Corded Ware culture and Sintashta culture.

The earliest known chariots have been found in Sintashta burials. This culture is thought to be where this technology began. It then spread across the Old World and was very important in ancient warfare. Sintashta settlements are also known for their intense copper mining and bronze metallurgy (metalworking). This is unusual for a steppe culture.

It was hard to find Sintashta sites under later settlements. So, the culture was only recently separated from the Andronovo culture. It is now seen as a separate part of the larger 'Andronovo horizon'.

Andronovo Culture

The Andronovo culture is a group of similar local Bronze Age Indo-Iranian cultures. They thrived around 2000–1450 BC in western Siberia and the central Eurasian Steppe. It is better described as an archaeological complex or group of related sites. The name comes from the village of Andronovo, where graves with skeletons and decorated pottery were found in 1914.

The older Sintashta culture (2050–1900 BCE), once part of the Andronovo culture, is now seen separately. But it is considered its predecessor and part of the wider Andronovo group.

Currently, only two sub-cultures are considered part of Andronovo culture:

- Alakul (2000–1700 BC) between Oxus (now Amu Darya) and Jaxartes, Kyzylkum desert

- Fëdorovo (2000–1450 BC) in southern Siberia (earliest signs of cremation and fire cult)

The area of this culture is huge and hard to define exactly. To the west, it overlaps with the similar, but different, Srubna culture. To the east, it reaches into the Minusinsk depression. Some sites are as far west as the southern Ural Mountains. Other sites are scattered as far south as the Kopet Dag (Turkmenistan), the Pamir (Tajikistan), and the Tian Shan (Kyrgyzstan). The northern border roughly matches where the Taiga begins.

Around the middle of the 2nd millennium, the Andronovo cultures began to move strongly eastward. They mined copper ore in the Altai Mountains. They lived in villages with up to ten sunken log cabin houses, some as large as 30m by 60m. Burials were in stone boxes or stone enclosures with buried timber rooms.

Their economy was based on herding cattle, horses, sheep, and goats. While farming has been suggested, no clear proof has been found.

Studies link the Andronovo culture to early Indo-Iranian languages. It might have also overlapped with early Uralic-speaking areas to its north.

Based on its use by Indo-Aryans in Mitanni and Vedic India, and its presence at the Sintashta site around 1900-2000 BCE, Kuz'mina (1994) argues that the chariot supports the idea of Andronovo being Indo-Iranian. Bactria-Margiana burials have also been found with a foal, showing more links to the steppes.

Mallory admits it is hard to prove that expansions from Andronovo reached northern India. He says attempts to link Indo-Aryans to sites like Beshkent and Vakhsh cultures "only gets the Indo-Iranian to Central Asia, but not as far as the seats of the Medes, Persians or Indo-Aryans." He developed the "kulturkugel" model. This model says Indo-Iranians adopted Bactria-Margiana cultural traits but kept their language and religion as they moved into Iran and India. Fred Hiebert also agrees that an expansion of the BMAC into Iran and the Indus Valley border is "the best candidate for an archaeological correlate of the introduction of Indo-Iranian speakers to Iran and South Asia." According to Narasimhan et al. (2018), the Andronovo culture expanded towards the BMAC through the Inner Asia Mountain Corridor.

Bactria-Margiana Culture

The Bactria-Margiana Culture, also called "Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex," was a non-Indo-European culture. It influenced the Indo-Iranians. It was located in what is now northwestern Afghanistan and southern Turkmenistan. Proto-Indo-Iranian arose because of this influence.

The Indo-Iranians also borrowed their unique religious beliefs and practices from this culture. According to Anthony, the Old Indic religion probably started among Indo-European immigrants. This happened in the area where the Zeravshan River (now Uzbekistan) and Iran meet. It was "a mix of old Central Asian and new Indo-European elements." It borrowed "distinctive religious beliefs and practices" from the Bactria–Margiana culture. At least 383 non-Indo-European words were borrowed from this culture. These include the god Indra and the ritual drink Soma.

Artifacts typical of the Bactria-Margiana (southern Turkmenistan/northern Afghanistan) found in burials at Mehrgarh and Balochistan are explained by people moving from Central Asia to the south. Indo-Aryan tribes might have been in the BMAC area by 1700 BCE at the latest. This matches the decline of that culture.

From the BMAC, the Indo-Aryans moved into the Indian subcontinent. According to Bryant, the Bactria-Margiana items found in Mehrgarh and Baluchistan burials are "evidence of an archaeological intrusion into the subcontinent from Central Asia during the commonly accepted time frame for the arrival of the Indo-Aryans."

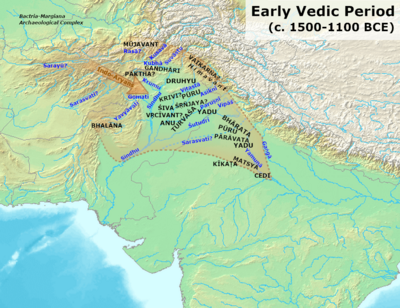

Multiple Waves into Northern India

According to Parpola, Indo-Aryan groups moved into South Asia in several waves. This explains the different ideas found in the Rig Veda. It might also explain the different Indo-Aryan cultures in the later Vedic period. These include the Vedic culture in the Kuru Kingdom (western Ganges plain) and the culture of Greater Magadha (eastern Ganges plain), which led to Jainism and Buddhism.

In 1998, Parpola suggested a first wave of immigration as early as 1900 BCE. This matches the Cemetery H culture and the Copper Hoard culture (or Ochre Coloured Pottery culture). He also suggested an immigration to the Punjab around 1700–1400 BCE. In 2020, Parpola proposed an even earlier wave of proto-Indo-Iranian speakers from the Sintashta culture into India around 1900 BCE. This was linked to the Copper Hoard Culture. This was followed by a pre-Rig Vedic Indo-Aryan migration:

It seems, then, that the earliest Aryan-speaking immigrants to South Asia, the Copper Hoard people, came with bull-drawn carts (Sanauli and Daimabad) via the BMAC and had Proto-Indo-Iranian as their language. They were, however, soon followed (and probably at least partially absorbed) by early Indo-Aryans.

Parpola links this pre-Rig-Vedic wave of migration by early Indo-Aryans to "the early (Ghalegay IV–V) phase of the Gandhara Grave culture" and the Atharva Veda tradition. He also links it to the Petrovka culture. The Rig-Vedic wave came several centuries later, "perhaps in the fourteenth century BCE." Parpola links this to the Fedorovo culture.

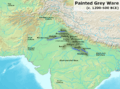

According to Kochhar, there were three waves of Indo-Aryan immigration after the main Harappan phase:

- The "Murghamu" (Bactria-Margiana culture) related people. They entered Balochistan at Pirak, Mehrgarh south cemetery, and other places. They later mixed with the post-urban Harappans during the late Harappan Jhukar phase (2000–1800 BCE).

- The Swat IV people who helped found the Harappan Cemetery H phase in Punjab (2000–1800 BCE).

- The Rigvedic Indo-Aryans of Swat V. They later absorbed the Cemetery H people and led to the Painted Grey Ware culture (PGW) (to 1400 BCE).

Gandhara Grave and Ochre Coloured Pottery Cultures

The common idea for how Indo-European languages entered India is that Indo-Aryan migrants crossed the Hindu Kush. They formed the Gandhara grave culture (or Swat culture) in what is now the Swat valley. They then moved into the areas near the Indus or Ganges (likely both). The Gandhara grave culture, which started around 1600 BCE and thrived from about 1500 BCE to 500 BCE in Gandhara (modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan), is thus the most likely place for the earliest people of Rigvedic culture. Around 1800 BCE, there was a big cultural change in the Swat Valley with the rise of the Gandhara grave culture. With its new pottery, burial customs, and the horse, the Gandhara grave culture is a strong candidate for early Indo-Aryan presence. The two new burial customs—flexed burial in a pit and cremation in an urn—were both practiced in early Indo-Aryan society, according to early Vedic texts. Horse-related items show how important the horse was to the Gandharan grave culture's economy. Two horse burials also show the horse's importance in other ways. Horse burial is a custom the Gandharan grave culture shares with Andronovo.

Parpola (2020) states:

The dramatic new discovery of cart burials dated to c. 1900 at Sinauli have been reviewed in this paper, and they support my proposal of a pre-Ṛvedic wave (now set of waves) of Aryan speakers arriving in South Asia and their making contact with the Late Harappans.

Two Waves of Indo-Iranian Migration

The Indo-Iranian migrations happened in two waves. These belong to the second and third stages of Beckwith's description of Indo-European migrations. The first wave was the Indo-Aryan migration into the Levant. This seems to have founded the Mitanni kingdom in northern Syria (about 1600–1350 BCE). It also included the migration southeast of the Vedic people, over the Hindu Kush into northern India. Christopher I. Beckwith suggests that the Wusun, an Indo-European people in Inner Asia in ancient times, were also of Indo-Aryan origin. The second wave is seen as the Iranian wave.

First Wave – Indo-Aryan Migrations

Mitanni Kingdom

Mitanni was a Hurrian-speaking state in northern Syria and southeast Anatolia from about 1600 BCE – 1350 BCE.

One idea is that it was founded by an Indo-Aryan ruling class. They governed a mostly Hurrian population. Mitanni became a strong regional power after the Hittites destroyed Amorite Babylon. Also, a series of weak Assyrian kings created a power vacuum in Mesopotamia. Early in its history, Mitanni's main rival was Egypt under the Thutmosids. But with the rise of the Hittite empire, Mitanni and Egypt formed an alliance. This was to protect their shared interests from the Hittite threat.

At its strongest, in the 14th century BCE, Mitanni had outposts around its capital, Washukanni. Archaeologists believe this was at the source of the Khabur River. Their influence is shown by Hurrian place names, personal names, and a unique type of pottery spread across Syria and the Levant. Eventually, Mitanni fell to Hittite and later Assyrian attacks. It became a province of the Middle Assyrian Empire.

The earliest written proof of an Indo-Aryan language is not in India. It is in northern Syria, where the Mitanni kingdom was. The Mitanni kings took Old Indic throne names. Old Indic technical terms were used for horse-riding and chariot-driving. The Old Indic term r'ta, meaning "cosmic order and truth," a key idea in the Rigveda, was also used in the Mitanni kingdom. Old Indic gods, including Indra, were also known in the Mitanni kingdom.

Scholars do not believe that the Indo-Aryans of Mitanni came from India. They also do not believe that the Indo-Aryans of India came from Mitanni. This leaves migration from the north as the only likely scenario. The presence of some Bactria-Margiana loan words in Mitanni, Old Iranian, and Vedic further supports this.

North India – Vedic Culture

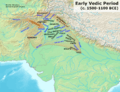

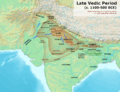

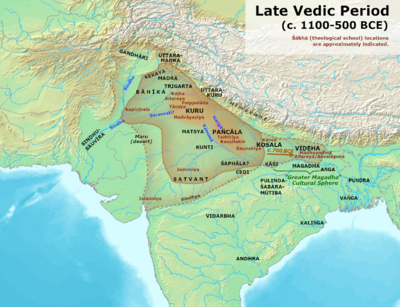

| Spread of Vedic culture |

|---|

Kingdoms, tribes and theological schools of the Late Vedic Period.

|

Spread of Vedic-Brahmanic Culture

During the Early Vedic Period (about 1500–800 BCE), Indo-Aryan culture was centered in northern Punjab, or Sapta Sindhu. During the Later Vedic Period (about 800–500 BCE), Indo-Aryan culture began to spread into the western Ganges Plain. It focused on the Vedic Kuru and Panchala areas. It also had some influence in the central Ganges Plain after 500 BCE. Sixteen Mahajanapada (great states) developed on the Ganges Plain. Of these, the Kuru and Panchala became the most important centers of Vedic culture in the western Ganges Plain.

The Central Ganges Plain, where Magadha became powerful (forming the base of the Maurya Empire), was a distinct cultural area. New states arose here after 500 BCE during the "Second urbanization." This region "was where rice was first grown in the Indian subcontinent. By 1800 BCE, it had an advanced Neolithic population linked to the sites of Chirand and Chechar." In this region, the Shramanic movements thrived, and Jainism and Buddhism began.

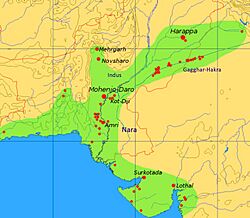

Indus Valley Civilization

The Indo-Aryan migration into northern Punjab began shortly after the decline of the Indus Valley civilisation (IVC). The "Aryan Invasion Theory" claimed this decline was caused by "invasions" of violent Aryans who conquered the IVC. This "Aryan Invasion Theory" is not supported by archaeological and genetic data. It does not represent the "Indo-Aryan migration theory."

Decline of Indus Valley Civilisation

The decline of the IVC from about 1900 BCE started before the Indo-Aryan migrations. It was caused by dry conditions due to shifting monsoons. A regional cultural break happened during the 2nd millennium BCE. Many Indus Valley cities were abandoned then. At the same time, many new settlements appeared in Gujarat and East Punjab. Other settlements, like those in the western Bahawalpur region, grew in size.

Jim G. Shaffer and Lichtenstein say that in the 2nd millennium BCE, major "location processes" happened. In eastern Punjab, 79.9% of sites changed settlement status. In Gujarat, 96% did. According to Shaffer & Lichtenstein:

It is evident that a major geographic population shift accompanied this 2nd millennium BCE localisation process. This shift by Harappan and, perhaps, other Indus Valley cultural mosaic groups, is the only archaeologically documented west-to-east movement of human populations in the Indian subcontinent before the first half of the first millennium B.C.

Continuity of Indus Valley Civilization

According to Erdosy, the ancient Harappans were not very different from modern people in Northwestern India and present-day Pakistan. Skull measurements showed similarity with ancient peoples of the Iranian plateau and Western Asia.

According to Kennedy, there is no proof of "population disruptions" after the Harappa culture declined. Kenoyer notes that no biological evidence can be found for large new populations in post-Harappan communities. Hemphill notes that "patterns of phonetic affinity" between Bactria and the Indus Valley Civilisation are best explained by "a pattern of long-standing, but low-level bidirectional mutual exchange."

According to Kennedy, the Cemetery H culture "shows clear biological affinities" with the earlier population of Harappa. The archaeologist Kenoyer noted that this culture "may only reflect a change in the focus of settlement organization from that which was the pattern of the earlier Harappan phase and not cultural discontinuity, urban decay, invading aliens, or site abandonment, all of which have been suggested in the past." Recent excavations in 2008 at Alamgirpur, Meerut District, seemed to show an overlap between Harappan and Painted Grey Ware culture (PGW) pottery. This suggests cultural continuity.

Connection with Indo-Aryan Migrations

According to Kenoyer, the decline of the Indus Valley Civilisation is not explained by Aryan migrations. These migrations happened after the IVC declined. Yet, according to Erdosy:

Evidence in material culture for systems collapse, abandonment of old beliefs and large-scale, if localised, population shifts in response to ecological catastrophe in the 2nd millennium B.C. must all now be related to the spread of Indo-Aryan languages.

Erdosy tested ideas from language evidence against ideas from archaeological data. He states there is no proof of "invasions by a barbaric race enjoying technological and military superiority." But there is "some support [...] for small-scale migrations from Central Asia to the Indian subcontinent in the late 3rd/early 2nd millennia BCE." According to Erdosy, the suggested movements within Central Asia can be seen as a process. This replaces simple ideas of "diffusion," "migrations," and "invasions."

Scholars have argued that the historical Vedic culture is a mix. It combines the immigrating Indo-Aryans with what remained of the local civilization, like the Ochre Coloured Pottery culture. Such remnants of IVC culture are not very clear in the Rigveda. The Rigveda focuses on chariot warfare and nomadic herding, which is very different from an urban civilization.

Inner Asia – Wusun and Yuezhi

According to Christopher I. Beckwith, the Wusun were also of Indo-Aryan origin. They were an Indo-European people in Inner Asia in ancient times. From the Chinese term Wusun, Beckwith rebuilds the Old Chinese *âswin. He compares this to the Old Indic aśvin, meaning "the horsemen." This is the name of the Rigvedic twin horse gods. Beckwith suggests the Wusun were an eastern leftover of the Indo-Aryans. They had been suddenly pushed to the edges of the Eurasian Steppe by the Iranian peoples in the 2nd millennium BCE.

Chinese sources first mention the Wusun as vassals (people under the rule of another) in the Tarim Basin. They were vassals of the Yuezhi, another Indo-European people. Around 175 BCE, the Yuezhi were completely defeated by the Xiongnu. The Yuezhi then attacked the Wusun and killed their king, taking the Ili Valley from the Saka (Scythians) soon after. In return, the Wusun settled in the former Yuezhi lands as vassals of the Xiongnu.

The son of the Wusun king was adopted by the Xiongnu king and made leader of the Wusun. Around 130 BCE, he attacked and completely defeated the Yuezhi. He settled the Wusun in the Ili Valley. After the Yuezhi were defeated by the Xiongnu in the 2nd century BCE, a small group, the Little Yuezhi, fled south. Most migrated west to the Ili Valley, where they pushed out the Sakas (Scythians). Driven from the Ili Valley by the Wusun, the Yuezhi moved to Sogdia and then Bactria. They are often identified with the Tókharoi and Asii in old texts. They then expanded into northern Indian subcontinent. One branch of the Yuezhi founded the Kushan Empire. The Kushan empire stretched from Turpan in the Tarim Basin to Pataliputra on the Indo-Gangetic Plain at its largest. It played an important role in developing the Silk Road and spreading Buddhism to China.

Soon after 130 BCE, the Wusun became independent of the Xiongnu. They became trusted allies of the Han dynasty and a powerful force in the region for centuries. With the rise of steppe groups like the Rouran, the Wusun moved into the Pamir Mountains in the 5th century CE. They are last mentioned in 938 when a Wusun chief paid tribute to the Liao dynasty.

Second Wave – Iranians

The first Iranians to reach the Black Sea might have been the Cimmerians in the 8th century BCE. But their language links are not certain. They were followed by the Scythians, who would control the area. At their peak, they stretched from the Carpathian Mountains in the west to the eastern edges of Central Asia in the east. For most of their time, the Scythians were based in what is now Ukraine and southern European Russia. Sarmatian tribes, like the Roxolani, Iazyges, and Alans, followed the Scythians westward into Europe in the late centuries BCE and the 1st and 2nd centuries CE. The large Sarmatian tribe of the Massagetae, living near the Caspian Sea, were known to the early rulers of Persia. In the east, the Scythians lived in several areas in Xinjiang.

The Medes, Parthians, and Persians began to appear on the western Iranian Plateau from about 800 BCE. They then remained under Assyrian rule for several centuries. Around the 1st millennium CE, the Kambojas, the Pashtuns, and the Baloch began to settle on the eastern edge of the Iranian Plateau. This was on the mountainous border of northwestern and western Pakistan. They pushed out the earlier Indo-Aryans from the area.

In Central Asia, the Turkic languages have taken over from Iranian languages. This happened because of the Turkic migration in the early centuries CE. In Eastern Europe, Slavic and Germanic peoples absorbed the local Iranian languages (Scythian and Sarmatian). Major Iranian languages still spoken today include Persian, Pashto, Kurdish, and Balochi, along with many smaller ones.

Human Studies: Elite Influence and Language Change

Elite Dominance

Small groups can change a larger cultural area. A small group of powerful men might have led to a language shift in northern India. Thapar notes that Indo-Aryan chiefs might have protected non-Aryan farmers. They offered a system of support, putting the chiefs in a higher position. This would have involved speaking two languages. It led to local people adopting Indo-Aryan languages. According to Parpola, local leaders joined "small but powerful groups" of Indo-European-speaking migrants. These migrants had an attractive social system, good weapons, and luxury goods that showed their status. Joining these groups was good for local leaders. It made them stronger and gave them more advantages. These new members were further connected through marriages.

Renfrew: How Languages Are Replaced

Basu et al. refer to Renfrew, who described four ways languages are replaced:

- The population-subsistence model: The incoming group has better technologies, making them dominant. This can lead to significant gene flow and genetic changes. But it can also lead to cultural mixing, where technologies are adopted, but there is less genetic change.

- Extended trading systems: These led to a common language (lingua franca). Some gene flow is expected here.

- The elite dominance model: "a relatively small but well-organized group [...] take[s] over the system." Because the elite is small, its genetic influence might be small. But "preferential access to marriage partners" might lead to a relatively strong influence on the gene pool. Gender differences also matter: incoming elites often mostly men. They do not affect female genetic material but can influence male genetic material.

- System collapse: Territorial borders change, and elite dominance might appear for a while.

David Anthony: Elite Recruitment

David Anthony, in his "revised Steppe hypothesis," notes that Indo-European languages probably did not spread through simple "folk migrations." Instead, they were introduced by important religious and political leaders. Larger groups of people then copied these leaders. Anthony gives the example of the Southern Luo-speaking Acholi in northern Uganda in the 17th and 18th centuries. Their language spread quickly in the 19th century. Anthony notes that "Indo-European languages probably spread in a similar way among the tribal societies of prehistoric Europe." They were carried by "Indo-European chiefs" and their "ideology of political clientage." Anthony notes that "elite recruitment" might be a good term for this system.

Michael Witzel: Small Groups and Cultural Mixing

Michael Witzel refers to Ehret's model. This model emphasizes the "osmosis" or "billiard ball" effect of cultural transmission. According to Ehret, ethnicity and language can change relatively easily in small societies, due to the cultural, economic, and military choices made by the local people. The group bringing new traits might initially be small. They might contribute fewer features than the local culture already has. The new combined group might then start a repeating, expanding process of ethnic and language change.

Witzel notes that "arya/ārya" does not mean a specific "people" or "racial" group. It means all those who joined the tribes speaking Vedic Sanskrit and followed their cultural rules (like rituals, poetry, etc.). According to Witzel, "there must have been a long period of acculturation between the local population and the 'original' immigrants speaking Indo-Aryan." Witzel also notes that Indo-Aryan speakers and the local population must have been bilingual. They spoke each other's languages and interacted before the Rg Veda was written in the Punjab.

Salmons: Changes in Community Structure

Joseph Salmons notes that Anthony provides little concrete proof or arguments. Salmons is critical of "prestige" as a main factor in the shift to Indo-European languages. He refers to Milroy, who says "prestige" is "a cover term for a variety of very distinct notions." Instead, Milroy suggests "arguments built around network structure." Salmons also notes that Anthony includes some of these arguments, "including political and technological advantages." According to Salmons, the best model is by Fishman.

... understands shift in terms of geographical, social, and cultural "dislocation" of language communities. Social dislocation, to give the most relevant example, involves "siphoning off the talented, the enterprising, the imaginative and the creative" ([Fishman] 1991: 61), and sounds strikingly like Anthony's 'recruitment' scenario.

Salmons himself argues that "systematic changes in community structure are what drive language shift." This includes Milroy's network structures. The core of this view is a key part of modernization. It is a shift from local community organization to regional (state or national or international) organizations. Language shift is linked to this move from mostly "horizontal" community structures to more "vertical" ones.

Literary Research: Similarities and Migration Clues

Similarities

Mitanni Kingdom

The oldest writings in Old Indic, the language of the Rig Veda, are found not in India. They are in northern Syria, in Hittite records about one of their neighbors, the Hurrian-speaking Mitanni. In a treaty with the Hittites, the king of Mitanni swore by Hurrian gods. He then swore by the gods Mitrašil, Uruvanaššil, Indara, and Našatianna. These match the Vedic gods Mitra, Varuna, Indra, and Nāsatya (Aśvin). Horse-training terms from that time, found in a manual by "Kikkuli," contain Indo-Aryan loanwords. The personal names and gods of the Mitanni upper class also show strong signs of Indo-Aryan influence. Because Indo-Aryan is linked to horsemanship and the Mitanni upper class, it is thought that Indo-Aryan chariot drivers became rulers over a native Hurrian-speaking population around the 15th–16th centuries BCE. They were then absorbed into the local population and adopted the Hurrian language.

Brentjes argues that there is no cultural element from Central Asia, Eastern Europe, or the Caucasus in the Mitannian area. He also links the peacock design, found in the Middle East from before 1600 BCE (and likely before 2100 BCE), to an Indo-Aryan presence.

Scholars do not believe that the Indo-Aryans of Mitanni came from India. They also do not believe that the Indo-Aryans of India came from Mitanni. This leaves migration from the north as the only likely scenario. The presence of some Bactria-Margiana loan words in Mitanni, Old Iranian, and Vedic further supports this.

Iranian Avesta

The religious practices in the Rigveda and the Avesta (the main religious text of Zoroastrianism) are similar. Both have the deity Mitra. Priests are called hotṛ in the Rigveda and zaotar in the Avesta. Both use a ritual substance called soma in the Rigveda and haoma in the Avesta. However, the Indo-Aryan deva 'god' is related to the Iranian daēva 'demon'. Similarly, the Indo-Aryan asura 'name of a group of gods' (later, 'demon') is related to the Iranian ahura 'lord, god'. Authors from the 1800s and early 1900s explained this as a sign of religious rivalry between Indo-Aryans and Iranians.

Linguists like Burrow argue that the strong similarity between the Avestan of the Gāthās (the oldest part of the Avesta) and the Vedic Sanskrit of the Rigveda suggests that Zarathustra or at least the Gathas date closer to the usual Rigveda dating of 1500–1200 BCE, perhaps 1100 BCE or earlier. Boyce agrees with a later date of 1100 BCE and suggests an earlier date of 1500 BCE. Gnoli dates the Gathas to around 1000 BCE, with a possible 400-year range either way (1400 to 600 BCE). So, the date of the Avesta could also tell us about the date of the Rigveda.

The Avesta mentions Airyan Vaejah, one of the '16 lands of the Aryans'. Gnoli's interpretation of geographic references in the Avesta places the Airyanem Vaejah in the Hindu Kush. For similar reasons, Boyce excludes places north of the Syr Darya and western Iranian places. Skjaervo agrees that the Avestan texts suggest they were written somewhere in northeastern Iran. Witzel points to the central Afghan highlands. Humbach links Vaējah to words related to the Vedic root "vij," suggesting a region of fast-flowing rivers. Gnoli considers Choresmia (Xvairizem), the lower Oxus region, south of the Aral Sea, to be an outlying area in the Avestan world. However, according to , the likely homeland of Avestan is the area south of the Aral Sea.

Geographical Location of Rigvedic Rivers

The geography of the Rigveda seems to be centered on the land of the seven rivers. While the geography of the Rigvedic rivers is unclear in some early books of the Rigveda, the Nadistuti sukta is an important source for the geography of later Rigvedic society.

The Sarasvati River is one of the main Rigvedic rivers. The Nadistuti sukta in the Rigveda mentions the Sarasvati between the Yamuna to the east and the Sutlej to the west. Later texts like the Brahmanas and Mahabharata say that the Sarasvati dried up in a desert.

Scholars agree that at least some mentions of the Sarasvati in the Rigveda refer to the Ghaggar-Hakra River. The Afghan river Haraxvaiti/Harauvati Helmand is sometimes suggested as the location of the early Rigvedic river. Whether the name was transferred from the Helmand to the Ghaggar-Hakra is debated. If the early Rigvedic Sarasvati is identified with the Ghaggar-Hakra before it dried up (early 2nd millennium), it would place the Rigveda earlier than commonly thought by Indo-Aryan migration theory.

If river names and place names in the Rigvedic homeland were not Indo-Aryan, it would support an outside origin for the Indo-Aryans. However, most place names in the Rigveda and most river names in northwest India are Indo-Aryan. Non-Indo-Aryan names are common in the Ghaggar and Kabul River areas. The Ghaggar area was a post-Harappan stronghold for Indus populations.

Ecology

Climate change and drought might have caused both the first spread of Indo-European speakers and their migration from the steppes into south-central Asia and India.

Around 4200–4100 BCE, the climate changed, bringing colder winters to Europe. Between 4200 and 3900 BCE, many settlements in the lower Danube Valley were burned and abandoned. The Cucuteni-Tripolye culture showed more fortifications and moved eastward towards the Dniepr. Steppe herders, who spoke early Proto-Indo-European, spread into the lower Danube valley around 4200–4000 BCE. They either caused or took advantage of the collapse of Old Europe.

The Yamna culture adapted to a climate change between 3500 and 3000 BCE. The steppes became drier and cooler. Herds needed to be moved often to find enough food. Using wagons and riding horses made this possible. This led to "a new, more mobile form of pastoralism." It came with new social rules and ways to manage local migrations on the steppes. This created a new awareness of a distinct culture and of "cultural Others" who did not share these new ways.

In the 2nd millennium BCE, widespread dry conditions led to water shortages. This caused environmental changes in both the Eurasian steppes and South Asia. On the steppes, more humid conditions changed the plants. This led to "higher mobility and transition to nomadic cattle breeding." Water shortage also greatly affected South Asia:

This time was one of great upheaval for ecological reasons. Prolonged failure of rains caused acute water shortage in a large area, causing the collapse of sedentary urban cultures in south-central Asia, Afghanistan, Iran, and India, and triggering large-scale migrations. Inevitably, the new arrivals came to merge with and dominate the post-urban cultures.

The Indus Valley civilisation became localized. This means urban centers disappeared and were replaced by local cultures. This was due to a climatic change also noted in nearby Middle Eastern areas. As of 2016, many scholars believe that drought and less trade with Egypt and Mesopotamia caused the Indus Civilisation to collapse. The Ghaggar-Hakra river system relied on rain. Its water supply depended on the monsoons. The Indus valley climate became much cooler and drier from about 1800 BCE. This was linked to a general weakening of the monsoon at that time. The Indian monsoon declined, and dry conditions increased. The Ghaggar-Hakra river shrank towards the Himalaya foothills. This led to irregular and smaller floods, making flood-based farming less sustainable. Dry conditions reduced the water supply enough to cause the civilization's end and scatter its population eastward.

Indigenous Aryanism

Indian nationalistic opponents of the Indo-Aryan migration theory question it. Instead, they promote Indigenous Aryanism. They claim that speakers of Indo-Iranian languages (sometimes called Aryan languages) are "indigenous" (native) to the Indian subcontinent. Indigenous Aryanism has no support in current mainstream scholarship. It is contradicted by many studies on Indo-European migrations.

See also

- Early Indians

- List of ancient Indo-Aryan peoples and tribes

- Indo-Aryan peoples

- Indo-Aryan languages

- Indo-European migrations

- Ariana

- Tamil nationalism

Images for kids

-

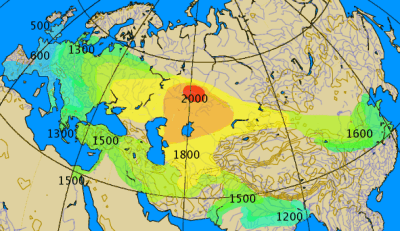

A map showing how Indo-European languages spread from about 4000 to 1000 BCE, based on the Kurgan hypothesis. The magenta area is the assumed original home (Samara culture, Sredny Stog culture). The red area shows where Indo-European speakers might have settled by about 2500 BCE; the orange area by 1000 BCE.

-

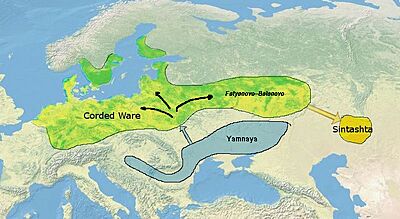

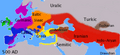

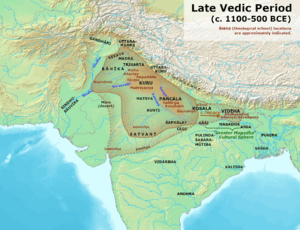

Map of the approximate maximal extent of the Andronovo culture. The formative Sintashta-Petrovka culture is shown in darker red. The location of the earliest spoke-wheeled chariot finds is indicated in purple. Adjacent and overlapping cultures (Afanasevo culture, Srubna culture and Bactria–Margiana cultures) are shown in green.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |