Paleontology in Oregon facts for kids

Paleontology in Oregon is all about studying ancient life in the U.S. state of Oregon. This includes finding and researching fossils there. Oregon's geologic record goes back about 400 million years. Back then, most of the land that is now Oregon was deep underwater.

Fossils show that Oregon stayed mostly submerged until the Paleocene period. The earliest fossils found are plants, corals, and tiny creatures called conodonts. During the Mesozoic era, Oregon had many seaways and volcanic islands. Fossils from this time include sea plants, invertebrates (animals without backbones), ichthyosaurs (ancient marine reptiles), pterosaurs (flying reptiles), and trace fossils like burrows.

In the Cenozoic era, Oregon's climate slowly got cooler. This led to the environments we see in the state today. Fossils from this era include plants and animals from both land and sea. You can find fish, amphibians, turtles, birds, mammals, and traces like eggs and animal tracks.

People have been studying fossils in Oregon for a long time. Early Native Americans even had stories to explain the fossils they found. By the mid-1800s, trained scientists started to notice Oregon's fossils. Today, this research helps us learn about climate change and extinction events from the past.

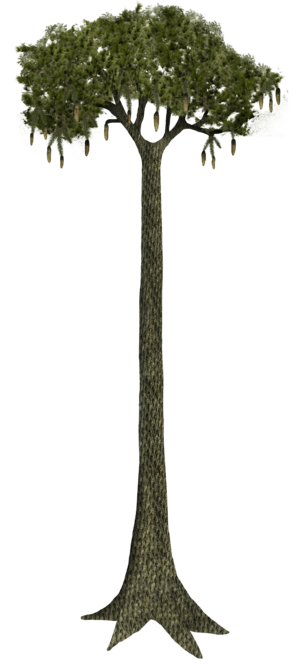

Oregon's official state fossil is the Metasequoia occidentalis, a type of dawn redwood tree.

Contents

Ancient Life in Oregon: Precambrian Times

There are no known rocks from the Precambrian era in Oregon. Scientists believe that during this time, the area that is now Oregon was deep under the ocean.

Paleozoic Era: Early Sea Life and Islands

Oregon's oldest known rocks are in the Blue Mountains and the Klamath Mountains. The very oldest rock is a limestone near Suplee. It is almost 400 million years old, from the Devonian period of the Paleozoic era.

These rocks contain fossils of conodonts, extinct corals, and brachiopods. This tells us that the area was a shallow sea. Most of Oregon stayed underwater until the Cenozoic era.

Carboniferous Period: Volcanic Islands and Swamps

Starting in the Carboniferous period, many volcanic islands formed in the region. These islands had warm, wet environments on land. Oregon's oldest plant fossils are from the Late Carboniferous period. They suggest a lagoon ecosystem.

These plant fossils include horsetails, ferns, scale trees, and conifer tree seeds. Rocks from the same time also have fossils of shallow water invertebrates. This shows that Oregon's volcanic islands were surrounded by coral reefs. This fits with Charles Darwin's ideas about how reefs form.

Permian Period: More Islands and Unique Animals

Volcanic island chains kept forming over Oregon through the Permian period. Fossils from this time are similar to those from the Carboniferous. However, no Permian plant fossils have been found yet.

One Permian snail species found in Oregon, Acteonina permiana, looks like snails from Europe and Asia. This supports the idea of plate tectonics, where continents move over time. Bits of Permian trilobites, including a unique species called Cummingella oregonensis, have been found in Oregon's Coyote Butte Formation.

Mesozoic Era: Age of Reptiles and Changing Seas

Oregon remained covered by shallow seas throughout the Mesozoic era. As temperatures rose during this era, sea levels also went up. Oregon's fossil plants and animals show these changes. New species adapted to deeper water or more tropical land conditions appeared.

Triassic Period: New Islands and First Vertebrates

During the Triassic period, Oregon's older volcanic chains merged to form new tropical islands. The only plant fossil from Oregon's Triassic rocks is Diplopora oregonensis. Like in the Paleozoic, shallow water invertebrates were common. These include sponges, ammonites, radiolarians, brachiopods, and the belemnite Aulacoceras.

A trace fossil called Chondrites (a type of burrow) has also been found. While corals are present, scientists are still debating if true coral reefs existed in Oregon during the Triassic.

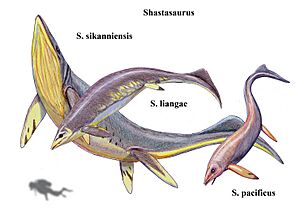

The oldest vertebrate (animal with a backbone) fossils in Oregon are from Triassic limestones in the Wallowa Mountains. These fossils include bones from an early ichthyosaur called Shastasaurus. Also, a new type of ancient marine reptile called a thalattosaur was found near Suplee.

Jurassic Period: Marine Crocodiles and Swamps

When the supercontinent Pangaea broke apart, a subduction zone formed in Oregon's ancient sea. This buried older rocks and created new volcanic islands. Oregon's Jurassic invertebrates, like the reef-building clam Lithiolus problematicus and the mussel-like Buchia piochii, show that shallow seas were still present.

Among Oregon's Jurassic vertebrate fossils are bones of marine crocodiles called Zoneait. These crocodiles likely swam with ichthyosaurs in Oregon's Jurassic seas. Plant fossils from this period show that the land became warmer and wetter, creating swampy areas. These fossils, found in the Coon Hollow Formation, include ferns, quillworts, cycads, and conifers.

Cretaceous Period: Rising Seas and Dinosaurs

Oregon's islands crashed into the Laramidian continent at the end of the Jurassic. This created a new western coastline during the Cretaceous period. Global temperatures reached their highest point in the mid-Cretaceous. This melted mountain ice and raised sea levels worldwide. The Pacific Ocean covered more of Oregon, stopping at the base of a coastal mountain range. These mountains created a tropical, rainy environment along the ancient coast.

Plant fossils from the Cretaceous are rare in Oregon because of the widespread seas. The few found are from small islands in the southwest and northeast. These plants were unique to the region. They include species of the fern Dicksonia, cycads Ctenis and Ctenophyllum, conifers Podozamites and Taxites, palm seeds Attalea, and the tree-fern Tempskya. The tree-fern fossils found with ammonites suggest an ancient shoreline.

Other Cretaceous invertebrates are similar to those from the Jurassic. Cretaceous rocks in Oregon have more types of trace fossils, including Planolites, Skolithos, Glossifungites, and Arenicolites. Oregon's oldest known crustacean, Hoploparia riddlensis, is also from the Cretaceous.

Oregon's Cretaceous fossil record shows more diverse vertebrates. In 2005, an amateur found a short-necked plesiosaur, nicknamed "Mitchell's Monster." This shows that plesiosaurs swam in Oregon's Cretaceous seas with ichthyosaurs. Other sites in Wheeler County have yielded Oregon's only known pterosaur, Bennettazhia oregonensis, and teeth from the extinct goblin shark Scapanorhynchus.

Only two non-avian dinosaur fossils have been found in Oregon. Both are single bones found in marine rocks. This means the dinosaur bodies likely floated out to sea. One is a toe bone from a large ornithopod (a plant-eating dinosaur) from the Early Cretaceous. The other is a hip bone fragment from a hadrosaur (duck-billed dinosaur) from the Late Cretaceous.

There are no geological records in Oregon of the K-Pg boundary. This is the time when a major extinction event ended the Mesozoic era.

Cenozoic Era: Cooling Climate and Mammals

Oregon's environment in the Cenozoic era changed as the Earth cooled. It went from tropical to temperate, then to glacial climates. As the shoreline moved westward, more diverse land animals appeared, including many extinct mammals.

Paleogene Period: Warm, Wet Forests and Early Mammals

Oregon's earliest Paleogene rocks show a warm, wet environment, similar to the southeastern U.S. today. Fossils from this time include pollen and leaves from ferns, spongeplants, hazelnuts, water elms, laurels, and horsetails. Trees like alder and birch, which became common later, first appeared along Oregon's Paleogene coast.

In western Oregon's ocean, the new Cascadia subduction zone helped create Oregon's modern Coast Range. This also made the ocean more productive, leading to more diverse sea animals. At least 25 species of mollusk, including several snails, are known from the Fern Ridge Dam area alone. Other marine invertebrates include echinoderms, foramenifera, brachiopods, scaphopods, shrimp, and crabs.

Shark teeth from over a dozen types have been found. These include dogfish, horn sharks, comb-toothed sharks, makos, tiger sharks, white sharks, and an ancient basking shark. Bony fish included mahi mahi, conger eels, rattails, ancestral billfish, cod, hake, and rockfish. Marine birds included auks, Hydrotherikornis oregonus, and the pelican-like Phocavis maritimus. Oregon's only known fossil egg was found in these rocks.

The volcanic activity from the subduction zone also formed the Cascade volcanic arc. These mountains blocked moist air from the Pacific, creating Oregon's High Desert. This is where the fossil-rich John Day Fossil Beds were formed. The earliest fossils there show a subtropical land environment.

The John Day area has many fossil seeds, fruit nuts, and wood. It is one of the few places where all three are preserved together. The plants included cinnamon, cycads, palms, the primitive sycamore Platanophyllum angustilobus, walnuts, magnolias, figs, grapes, coffee trees, cashews, and bananas. Oregon's earliest known land mammals lived here. These included the rhinoceros Hyrachyus, the early horse Orohippus, and the brontothere Telmatherium. Predators included Patriofelis, a cat-like creodont. These mammals shared the ecosystem with crocodiles like Pristichampsus and the tortoise Hadrianus.

Neogene Period: Grasslands and Diverse Mammals

From the late Paleogene to the Neogene period, Oregon's climate became drier. Its environments became more like today's. Grasses appeared and spread, leaving fossilized leaves in the John Day beds. Metasequoia occidentalis, a conifer similar to modern redwoods, grew widely. Mammals and other animals became more diverse and common.

Early additions included camels like Paratylopus and Gentilicamelus, and deer-like animals such as Hypertragulus. Later, perissodactyls (like horses and rhinos) appeared, such as Merychippus, Parahippus, Protapirus, and Diceratherium. Artiodactyls (like deer and pigs) included Dromomeryx and Blastomeryx. Large, trunked animals called proboscids like Gomphotherium and Platybelodon also lived here.

Rodents included the burrowing beaver Palaeocastor and horned gopher Mylagaulus. Predators included bear-dogs like Amphicyon, cat-like nimravids, enteldonts (giant pig-like animals), and early dog-like animals such as Cormocyon. Remains of an early primate, Ekgmowechashala, have also been found in the John Day fossil beds.

Quaternary Period: Ice Age Giants and Humans

Aquatic mammals first appeared along Oregon's early Neogene coast. Fossils of early pinnipeds (seals and sea lions) like Enaliarctos and the primitive walrus Proneotherium have been found in Lincoln County. Kolponomos newportensis, a bear-like aquatic carnivore, comes from similar rocks.

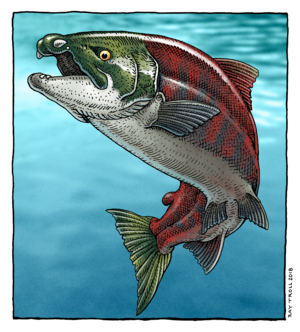

Whales like Aetiocetus and the primitive baleen whale Cophocetus oregonensis appear in Oregon's fossil record during this time. Sirenians (manatees and dugongs) and desmostylids (extinct marine mammals) have also been found. Scientists believe these animals ate clams and other mollusks, which matches fossil clam beds in the Coast Range. The saber-tooth salmon Oncorhynchus rastrosus also swam in Oregon's Neogene rivers.

Global cooling in the late Neogene led to glaciation in the Quaternary period. Oregon's mountains were covered in large ice caps. Evidence of ice cap changes is preserved in glacial lakes, like Glacier Lake. Large rocks called glacial erratics can be found across northern Oregon. Pluvial lakes (lakes formed by rain) were also common.

One important pluvial lake is Fossil Lake. It has Oregon's largest Pleistocene fossil collection. This collection includes typical Pleistocene megafauna (large Ice Age animals). These include Columbian mammoths, dire wolves, Ice Age bison, camels, ground sloths like Mylodon and Megatherium, and the short-faced bear Arctodus. The collection also has over 50 species of waterfowl, including grebes, cormorants, swans, gulls, flamingos, herons, and pelicans. Several salmon species are also found.

Pleistocene megafauna fossils are found across northern Oregon. These include the Tualatin mastodon, the McMinnville mammoth, and the Woodburn Teratornis (a giant bird). Mammoth tracks, about 43,000 years old, have been found at Fossil Lake. These tracks show a wounded mother mammoth and her young. A 9-meter bear trackway, similar in size to Arctodus, has been found near Lakeview.

Earthquakes and tsunamis from the Cascadian Subduction Zone continued through the Quaternary. At the end of the Last Glacial Maximum, the ice dam around Lake Missoula broke. This caused huge floods that covered much of Oregon between 19,000 and 13,000 years ago. Around 14,000 years ago, the Bonneville Flood added more water to these areas. These floods helped make the Willamette Valley fertile today by bringing in rich soils. It's unlikely these floods caused the extinction of Ice Age megafauna in Oregon.

The earliest evidence of humans in Oregon comes from human waste (coprolites) in Paisley Caves. These are dated to 14,300 years ago. Other early sites include a camp near Bandon (around 10,000 years ago) and sandals from Fort Rock Cave (around 9,000 years ago). The dates are close enough that humans might have played a part in the extinction of Oregon's Ice Age megafauna.

History of Paleontology in Oregon

Scientific Research

Professional Paleontologists

Oregon's first paleontologist was Thomas Condon. He started collecting fossils in 1861. Soldiers at Fort Dalles, where Condon was a church pastor, brought him fossil bones and teeth from the John Day fossil beds. Condon went with soldiers to the Harney Valley in 1862 to look for fossils. He found rich fossil deposits in the John Day River valley in 1863.

Condon realized his finds were very important. Since he wasn't a trained scientist, he sent some fossils to Othniel Charles Marsh at Yale University. Marsh asked Condon to guide an expedition to the area. Over the years, many fossil-hunting trips went to the John Day fossil beds. Many of Condon's fossils ended up in famous museums like the American Museum of Natural History and Smithsonian Institution. Most of his collection is at the University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History.

Edward Drinker Cope, who had a famous rivalry with Marsh called the "Bone Wars", also collected fossils in Oregon. He wrote about his findings in his book Vertebrata of the Tertiary Formations of the West.

Today, Oregon State University and the University of Oregon both have active paleontology research programs. Oregon State University's Terry Lab studies ancient environments and climate change. The University of Oregon's Vertebrate Paleontology Lab focuses on Oregon's extinct mammals. The University of Oregon's paleontology faculty also includes Greg Retallack, who studies fossilized soils. Many of the fossils mentioned above were found and studied by researchers in these programs.

John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, managed by the National Park Service, has also employed paleontologists since the 1980s. Dr. Nicholas Famoso is the current Paleontology Program Manager. Recent research from the park includes volcano ecology, dating rocks, and studying mammal ancient environments.

In 2005, the Oregon state legislature officially declared Metasequoia occidentalis as Oregon's state fossil.

Amateur Paleontology Work

Several groups in Oregon focus on citizen science in paleontology. The North American Research Group found the "Mitchell's Monster" plesiosaur and "Bernie" the Jurassic thalattosaurian. Another group is the Willamette Valley Pleistocene Project. They collect fossils from sites in McMinnville, Tualatin, Woodburn, Newberg, and King's Valley.

Famous People in Oregon Paleontology

Places to Find Fossils and Learn About Them

Fossil Localities

- Astoria Formation

- Blue Mountains

- Coyote Butte Formation

- Curry County

- Fossil Lake

- Keasey Formation

- Nye Formation

- Pittsburg Bluff Formation

- Wallowa Mountains

Protected Areas for Fossils

Natural History Museums

- University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History, Eugene

- Thomas Condon Paleontology Center, John Day Fossil Beds National Monument

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |