History of St. Louis facts for kids

The history of St. Louis is a long and exciting story! It began with ancient Native American people who built large mounds here. Later, French explorers arrived, and then Spain took control. In 1764, a trading company founded the city of St. Louis. Many French settlers moved here after France lost a big war.

St. Louis grew quickly because it was a great trading post on the Mississippi River. The fur trade was very profitable. The city became part of the U.S. after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Its location made it a major center for trade between different regions.

In the 1840s, many Irish and German immigrants came to St. Louis. Missouri was a state where slavery was allowed, but St. Louis was close to states where slavery was illegal. This led to many enslaved people trying to gain their freedom through lawsuits. One famous case was Dred Scott's, which went all the way to the US Supreme Court. The court's decision made tensions about slavery even worse, leading to the American Civil War. St. Louis stayed under Union control during the war.

After the war, St. Louis built more railroads and factories. The Eads Bridge was built over the Mississippi River in the 1870s. The city also created large parks like Forest Park. In 1876, St. Louis separated from St. Louis County to become its own independent city. This limited its growth later on. By the late 1800s, St. Louis was home to two Major League Baseball teams. Ragtime and blues music became popular here, with African Americans playing a huge role.

St. Louis hosted the 1904 World's Fair and the 1904 Summer Olympics, bringing millions of visitors. Many African Americans moved to the city for factory jobs during the Great Migration. The city faced tough times during the Great Depression and then helped with war industries during World War II.

After the war, many people moved to the suburbs. The city built new attractions like the Gateway Arch. Its construction became important for the civil rights movement as people fought for fair jobs. The city also tried to build new public housing projects, but some, like Pruitt–Igoe, didn't work out well and were torn down. Since the 1980s, parts of St. Louis, especially downtown, have seen new construction and improvements. The city is still working to reduce crime and make the city even better.

Contents

Early History: Before 1762

Long ago, in the 10th century, people of the Mississippian culture lived in the middle Mississippi Valley. They built more than two dozen large platform mounds where St. Louis is today. These mounds were connected to a huge city called Cahokia Mounds across the river. The Mississippian culture disappeared around the 14th century.

Later, Siouan-speaking groups like the Missouria and Osage tribes moved to the Missouri Valley. They lived in villages along the Missouri and Osage rivers. These tribes sometimes competed with others from the northeast, like the Sauk and Meskwaki. All these groups met the first European explorers.

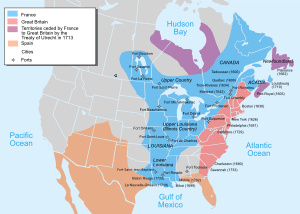

European explorers arrived in the area almost 100 years before St. Louis was founded. In 1673, explorer Louis Joliet and priest Jacques Marquette traveled down the Mississippi River. They passed the future site of St. Louis. Nine years later, French explorer La Salle claimed the entire Mississippi Valley for France. He named the region La Louisiane (Louisiana) after King Louis XIV. The area around the Ohio and Mississippi rivers was called the Illinois Country.

The French built settlements like Cahokia and Kaskaskia, Illinois. They also built trading towns such as Fort de Chartres and Ste. Genevieve, Missouri. Ste. Genevieve was the first European town in Missouri west of the Mississippi. From 1756 to 1760, the French and Indian War (part of the Seven Years' War) slowed down new settlements. France lost the war in 1763.

City Founding and Early Years: 1763–1803

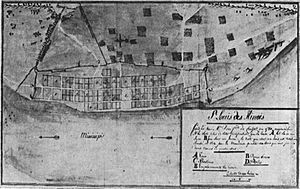

In 1763, a new governor in Louisiana, Jean-Jacques Blaise d'Abbadie, changed colonial rules. He gave special trading rights to companies to help the economy. One of these was led by Pierre Laclede. In August 1763, Laclede and his stepson Auguste Chouteau decided to build a fur trading post. They chose a spot on the west bank of the Mississippi River, south of where the Missouri River joins it.

On February 15, 1764, Chouteau and about 30 men officially started the settlement of St. Louis. Laclede arrived later that year and drew up detailed plans for the village. He designed the street grid and market area. French settlers from areas now controlled by Great Britain started moving to St. Louis in 1764. The local French governor moved to St. Louis in 1765 and began giving out land grants.

Spain secretly gained control of Louisiana in 1762. But because of travel times and a rebellion, Spain didn't officially take over St. Louis until May 1770. After the change, Spain allowed the French land grants to stay. Spanish soldiers helped keep the peace.

Most settlers were farmers. By the 1790s, nearly 6,000 acres (24 km2) were farmed around St. Louis. But fur trading was the main business and was much more profitable. The first Catholic church was built in 1770. St. Louis got its first resident priest in 1776, making religious life more common.

The French settlers brought both African and Native American slaves to St. Louis. Most worked as domestic servants, while others were farm laborers. In 1769, Spain banned Native American slavery in Louisiana. However, the practice was common among the French Creoles in St. Louis. Spanish governors stopped the Native American slave trade but allowed existing slaves and their children to remain enslaved. A 1772 census showed 637 people in the village: 444 white and 193 African slaves. St. Louis grew slowly during the 1770s and 1780s.

St. Louis During the American Revolutionary War

When the American Revolutionary War began, the Spanish governor in New Orleans, Bernardo de Galvez, helped the American rebels. He sent them weapons, food, and supplies. Spanish leaders in St. Louis also helped the Americans, especially George Rogers Clark's forces.

Spain officially joined the war in June 1779, helping the Americans and French. The British then planned to attack St. Louis and other Mississippi outposts. But the city was warned and began building defenses.

On May 26, 1780, a British commander led an attack on St. Louis. His force was mostly Native American allies. But the city's defenses and some Native American groups leaving the fight forced them to retreat. Even though they failed to capture the town, the attackers burned many St. Louis farms. They also captured some livestock and prisoners of war. A counterattack by the settlers against British forts in the Midwest stopped any future attacks on St. Louis.

After the war ended in 1783, many French Creole families moved to Spanish-controlled land on the west bank. They wanted to avoid American rule. Wealthy merchants like Charles Gratiot, Sr. and Gabriel Cerre moved here. The Gratiot and Cerre families married into the Chouteau family, creating a powerful Creole society in the 1780s and 1790s. These families also had ties to Spanish government officials.

Changing Flags: From France to the United States

In the 1790s, towns near St. Louis grew as small farmers sold their land to large families like the Cerres, Gratiots, and Chouteaus. These farmers moved to towns like Carondelet, St. Charles, and Florissant. By 1800, only 43% of the area's population lived in the main village of St. Louis.

In October 1800, the Spanish government secretly gave the Louisiana territory back to France. Spain officially transferred control in October 1802. However, Spanish leaders still managed St. Louis during the short time France owned it. Soon after, American negotiators bought Louisiana, including St. Louis.

On March 8 or 9, 1804, the Spanish flag was lowered in St. Louis. According to local stories, the French flag was then raised. The very next day, March 10, 1804, the French flag was replaced by the flag of the United States. This event is sometimes called "Three Flags Day."

Growth and the Civil War: 1804–1865

Trade, Challenges, and Rapid Growth

After the Louisiana Purchase, St. Louis remained a center for the fur trade. The Chouteau family and Manuel Lisa's Missouri Fur Company led these operations. Because it was a major trading post, St. Louis was the starting point for the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1804.

American and other immigrant families began arriving in St. Louis in the 1810s. They opened new businesses, including printing and banking. Joseph Charless published the first newspaper west of the Mississippi, the Missouri Gazette, in 1808. The first banks opened in 1816 and 1817. But poor management and an economic crisis called the Panic of 1819 caused them to close.

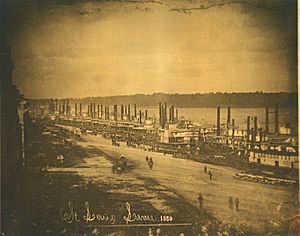

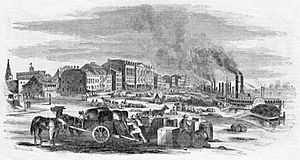

The Panic of 1819 slowed down business in St. Louis until the mid-1820s. However, by 1824, St. Louis businesses began to recover. This was largely due to the arrival of the steamboat. The first steamboat, the Zebulon M. Pike, arrived in St. Louis on August 2, 1817. Rapids north of the city made St. Louis the farthest north many large riverboats could go. The Pike and other ships quickly turned St. Louis into a busy inland port.

More goods became available in St. Louis as the economy improved, thanks to steamboats. New stores, banks, and wholesale businesses opened in the late 1820s and early 1830s. The fur trade remained a major industry into the 1830s. In 1822, Jedediah Smith joined a St. Louis fur trading company. He later became famous for exploring the American West. New fur trade companies, like the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, created new trails to the west. Even though beaver fur became less popular in the 1840s, St. Louis continued to be a hub for buffalo hide and other furs.

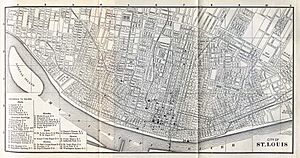

New buildings also encouraged growth. The County Courthouse was built in the late 1820s. A new City Hall was built next to the river in 1833. A military post moved closer to the city to Jefferson Barracks in 1827. The St. Louis Arsenal was built in south St. Louis the same year. The 1830s saw huge population growth. By 1830, the population was 5,832. It doubled by 1840 to 16,439, and again by 1850 to 77,860.

City Improvements and Education

With rapid population growth, cholera became a big problem. In 1849, a major cholera epidemic killed nearly 5,000 people. This led to a new sewer system and the draining of a mill pond. Cemeteries were moved to the city's edge to Bellefontaine Cemetery and Calvary Cemetery to stop groundwater pollution.

In the same year, a huge fire started on a steamboat. It spread to 23 other boats and destroyed a large part of the city center. The St. Louis landing was greatly improved in the 1850s. Engineers, including Robert E. Lee, built levees on the Illinois side of the river. This directed water towards Missouri to remove sand bars that blocked the landing. The city's water system, started in the 1830s, was also constantly improved.

Most early St. Louis residents could not read or write in the 1810s. Wealthy merchants, however, bought books for private libraries. Early schools charged fees and mostly taught in French. The Catholic Church made the first big effort in education. In 1818, they opened Saint Louis Academy, which later became Saint Louis University. In 1832, it became the first chartered university west of the Mississippi River. Its medical school opened in 1842. However, the university mainly served students studying to become priests. The Catholic Church offered more widespread education at parochial schools in the 1840s. In 1853, William Greenleaf Eliot founded a second university, Washington University in St. Louis.

Public education in St. Louis began in 1838 with two elementary schools. The system quickly grew in the 1840s. By 1854, there were 27 schools serving nearly 4,000 students. In 1855, the district opened a high school, which was the first public high school west of the Mississippi River. It is now known as Central VPA High School. By 1860, nearly 12,000 students were enrolled. The district also opened a school for teachers in 1857, which later became Harris–Stowe State University.

Entertainment options also increased. The first theater production in St. Louis opened in 1819. In the late 1830s, a 35-member orchestra played briefly. Another orchestra opened in 1860 and played many concerts.

Slavery, Immigration, and Local Conflicts

Missouri was a slave state. In the 1840s, the number of enslaved people grew, but their percentage of the total population went down. By the 1850s, both the number and percentage declined. About 3,200 free Black people and enslaved people lived in St. Louis in 1850. They worked as servants, skilled workers, and on riverboats.

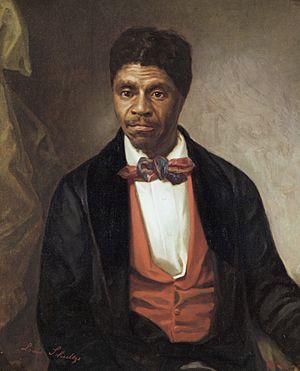

Some enslaved people were allowed to earn money. Some saved enough to buy their own freedom or that of family members. Others were freed by their owners, which happened more often in St. Louis than in rural areas. Some tried to escape using the Underground Railroad. Others tried to gain freedom through freedom suits, which were lawsuits. The first freedom suit in St. Louis was filed in 1805. More than 300 suits were filed before the Civil War.

The most famous case was that of Dred Scott and his wife Harriet. Their case, Dred Scott v. Sandford, started at the Old Courthouse. They argued they should be free because they had lived with their owner in free states. Although a state court first ruled in their favor, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against them in 1857. The Court said enslaved people could not be citizens. This decision also said the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional. This made the national debate about slavery much more intense.

During the economic growth of the 1830s, many Irish and German immigrants came to St. Louis. Writings by Gottfried Duden encouraged German immigration. Many Irish people came because of the Great Famine of 1845–1846 and a failed rebellion in 1848. St. Louis's reputation as a Catholic city also attracted some Irish settlers.

Local conflicts, called Nativist sentiments, grew in St. Louis in the late 1840s. This led to mob attacks and riots in 1844, 1849, and 1852. The 1844 riots happened because people were angry about human dissection at the Saint Louis University Medical College. Rumors of grave robbing spread. A mob of over 3,000 people attacked the college, destroying much of it. The worst nativist riot was in 1854. The local militia had to stop the fighting. 10 people were killed, 33 wounded, and 93 buildings were damaged. New election rules helped prevent fighting in future elections.

St. Louis During the American Civil War

Before the Civil War, the leaders of St. Louis changed. Anti-slavery Germans became more powerful than the Creole and Irish families. Frank P. Blair Jr. was one of these new leaders. He helped create a local militia loyal to the Union. This happened after Missouri Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson hinted that Missouri might leave the Union.

This local militia joined Union army forces at Jefferson Barracks, led by Nathaniel Lyon. On May 10, 1861, they cleared a Confederate camp outside the city. This event was called the Camp Jackson Affair. As the Confederates were marched back into town, some citizens attacked the Union forces. 28 civilians were killed.

Throughout the Civil War, St. Louis was a border city. It did not see major battles. Many people were worried about losing their enslaved workforce and the city's future. However, St. Louis became a leader in producing ammunition and supplies.

After the Camp Jackson Affair, there were no more military threats to Union control in St. Louis. But guerrilla activity continued in rural areas. Union General John C. Frémont placed the city under martial law in August 1861 to stop disloyalty. Union forces continued to suppress pro-Confederate demonstrations. The war badly hurt St. Louis's trade. The Confederacy blocked the Mississippi River, cutting off St. Louis's connection to eastern markets. The war also slowed the city's growth. The population only increased by 43,000 residents from 1860 to 1866.

St. Louis Becomes a Major City: 1866–1904

After the Civil War, St. Louis grew to become the fourth largest city in the United States. Only New York City, Philadelphia, and Chicago were bigger. The city also saw fast improvements in its buildings, transportation, and industries. This period ended with the 1904 World's Fair and 1904 Summer Olympics, both held in St. Louis.

City Improvements, Parks, and Education

During the Civil War, St. Louis's buildings and services were neglected. Another cholera outbreak happened in 1866, and typhoid fever was common. To fix this, St. Louis improved its water system. It also created a Board of Health to control polluting industries. The city's park system grew in the 1860s and 1870s. Tower Grove Park and Forest Park were created.

Railroads Connect the City

Railroad yards were built in Mill Creek Valley, making St. Louis a major transportation hub. Train stations, roundhouses, bridges over tracks, and many warehouses were built to support the growing railroad industry. Connections to the southwest and Texas improved in the 1870s with the Cotton Belt Railroad.

Railroads also needed connections across the Mississippi River to the east. From 1867 to 1874, work continued on the Eads Bridge over the Mississippi. The bridge officially opened on July 4, 1874.

To handle more train traffic, a new railroad terminal was built in 1875. But it wasn't big enough for all trains. A replacement station, called Union Station, opened on September 1, 1894. More railroads met at St. Louis's Union Station than any other city in the U.S. The station's platform was expanded in 1930. It served as the main passenger train terminal until the 1970s.

Education for All

By 1870, public and religious school systems had grown. St. Louis educators started the first public kindergarten in the United States in 1874. Ideas for a free library system began before the Civil War. After the war, the St. Louis Public School Library was created. In the 1870s and 1880s, various local libraries joined the school library system. In 1894, the school system made the library an independent organization, which became the St. Louis Public Library.

Schools for Black students had existed secretly and illegally in St. Louis since the 1820s. In 1864, a group of St. Louisans formed the Board of Education for Colored Schools. This board created schools for over 1,500 Black students without public money. After 1865, the St. Louis Board of Education funded Black schools, but their facilities were often poor. In 1875, after much effort, high school classes began at Sumner High School. It was the first high school for Black students west of the Mississippi. However, inequality in St. Louis schools remained a big problem.

Historians have discussed how school systems became more organized. Some say it was to control working-class people. Others say it was necessary to manage a fast-growing and complex system. These changes helped schools become less political and more efficient. They also introduced job training and longer schooling periods.

St. Louis Becomes an Independent City

When Missouri became a state in 1821, St. Louis County was created. St. Louis city was inside the county but not the same size. In the 1850s, county voters started to have more say over city taxes. In 1867, the county court could collect property taxes from St. Louis city. This helped the county but took money away from the city.

City residents then wanted changes. They wanted more representation in the county court, or for the city and county to combine, or for the city to become an independent city.

At a state meeting in 1875, leaders from the region agreed on a separation plan. A group from St. Louis county and city drew new boundaries. They proposed a final separation plan in 1876. The new city charter also tripled the city's size. It included new parks like Forest Park and the useful riverfront area. After a confusing election, voters approved the separation in December 1876.

Industry and Business Boom

In 1880, St. Louis's main industries included brewing, flour milling, slaughtering, paper making, and tobacco processing. Other industries made paint, bricks, and iron. In the 1880s, the city's population grew by 29 percent, from 350,518 to 451,770. This made it the country's fourth largest city. It also ranked fourth in the value of its manufactured goods. By 1890, there were over 6,148 factories. However, manufacturing growth slowed in the 1890s. An economic crisis in 1893 and too much grain made St. Louis mills less productive. Flour milling was cut in half, and other industries also suffered.

The arrival of railroads helped St. Louis's industrial success. With the Municipal Railroad System, St. Louis manufacturers could get their products to the East Coast much faster.

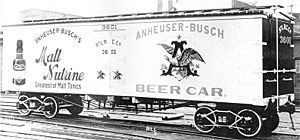

The brewing industry grew quickly with the arrival of Adam Lemp from Germany in 1842. He introduced lager beer, which became very popular. The industry expanded fast in the late 1850s, from 24 breweries in 1854 to 40 in 1860. Brewing became the city's largest industry by 1880. St. Louis breweries were innovators. Anheuser-Busch was the first to use refrigerated railroad cars for beer. They were also the first to sell pasteurized bottled beer.

St. Louis also had whiskey distilleries. Some were involved in the Whiskey Ring in the early 1870s. This was a plan by distillers and tax officials to avoid paying taxes. When the plan was discovered in 1875, over 100 people were charged with fraud.

In 1877, a general strike happened in the city. Workers demanded an eight-hour workday and an end to child labor.

Companies like Ralston-Purina and Anheuser-Busch were based in St. Louis. The city was also home to International Shoe and the Brown Shoe Company. The Graham Paper Company, the oldest and largest paper company west of the Mississippi, was also here. The Desloge Consolidated Lead Company, a major lead mining company, was headquartered downtown. In 1874, St. Louis insurance companies founded the Underwriters Salvage Corps to help reduce fire damage.

One downside of fast industrial growth was pollution. Brick making produced dust and paint making created lead dust. Beer and liquor brewing produced waste. The worst pollution was coal dust and smoke, which St. Louis was known for by the 1890s. Industries that processed animal products also created bad smells. Despite this, controlling pollution was difficult because people wanted to promote growth. One control measure started in 1880. Regulations were strict in some areas but loose in others. This encouraged factories to gather in industrial districts.

Besides industrial growth, the 1880s and 1890s saw many new commercial buildings downtown. The main shopping area was at Fourth Street and Washington Avenue. Banking and business were centered at Fourth and Olive streets. In the 1890s, major stores and businesses moved west. The Wainwright Building was one new building constructed. Designed by Louis Sullivan in 1891, it was the tallest building in the city then. It is still an example of early skyscraper design.

Culture and Entertainment Flourish

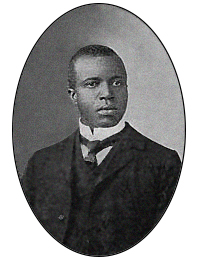

In September 1880, the St. Louis Choral Society opened as a musical orchestra and choir. This group gave annual concerts until 1906, when it was renamed the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra. In the 1890s, an area called Chestnut Valley became the home of St. Louis ragtime music. Many famous ragtime and jazz composers lived or played in St. Louis. These included W.C. Handy, Tom Turpin, and Scott Joplin. Joplin moved to St. Louis in 1901 and composed music here until 1907.

Baseball became popular after the Civil War. A team called the St. Louis Brown Stockings was founded in 1875. They were a founding member of the National League. The original Brown Stockings closed in 1878. A new team with the same name was founded in 1882. This team changed its name several times, finally becoming the St. Louis Cardinals in 1900. In 1902, another team moved to St. Louis and became the St. Louis Browns. From 1902 until the 1950s, St. Louis had two Major League Baseball teams.

Famous writers who lived in St. Louis included poets Sara Teasdale and T. S. Eliot, and playwright Tennessee Williams.

The 1904 World's Fair

Starting in the 1850s, St. Louis hosted yearly agricultural and mechanical fairs at Fairground Park. These fairs connected with regional manufacturers and farmers. By the 1880s, the focus on agriculture lessened. In 1883, a new St. Louis Exposition and Music Hall was built for industrial exhibits. In 1890, St. Louis tried to host the World's Columbian Exposition, but Chicago was chosen instead. In 1899, leaders from states that were part of the Louisiana Purchase met in St. Louis. They chose St. Louis to host a world's fair in 1904 to celebrate 100 years since the purchase.

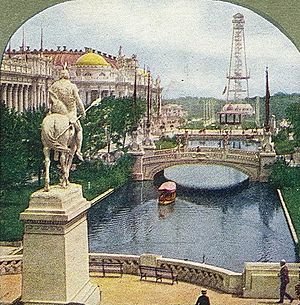

The fair directors chose the western part of Forest Park for the fair. This led to a boom in real estate and construction. Streetcar and rail service to the area improved. A new water filtration system was also put in place for St. Louis's water supply. The fair featured an "Ivory City" of twelve temporary exhibition palaces. One permanent palace became the St. Louis Art Museum after the fair. The fair celebrated American expansion and world cultures. It had exhibits on French fur-trading history and villages showing Eskimo and Filipino cultures. At the same time, the 1904 Summer Olympics were held in St. Louis. They took place at what is now the campus of Washington University in St. Louis.

City Changes and Urban Renewal: 1905–1980

City Improvements and Segregation

In the early 1900s, St. Louis started a building program to create parks and playgrounds. These were built in older neighborhoods. Parks Commissioner Dwight F. Davis continued to develop recreational facilities. He expanded tennis courts and built a public golf course in Forest Park. The St. Louis Zoo was built in Forest Park in the early 1910s.

Since the 1890s, St. Louis had tried to control its air pollution, but without much success. Damage to buildings and plants made the problem more obvious in the 1920s. The problem became very bad with the 1939 St. Louis smog, which made the sky black for three weeks. A ban on burning low-quality coal solved the problem in December 1939. The use of natural gas for heating also helped homeowners switch to cleaner fuels by the late 1940s.

During the 1904 World's Fair, ballooning was shown as a way to travel. In October 1907, an international balloon race, the Gordon Bennett Cup, was held in the city. The first airplane flight happened in late 1909. By the next year, an airfield was built in nearby Kinloch, Missouri. In October 1910, President Theodore Roosevelt visited St. Louis. He became the first president to fly in an airplane, taking off from that field. In 1925, local businessman Albert Lambert bought Kinloch Field. He expanded it and renamed it Lambert Field. In May 1927, Charles Lindbergh took off from Lambert Field. He was on his way to New York to start his solo non-stop flight across the Atlantic Ocean. In early 1928, the city of St. Louis bought the airport from Lambert. This made it the first city-owned airport in the United States. Lambert Field is still the area's main airport.

St. Louis had various Jim Crow laws, which enforced racial segregation. However, it generally had less racial violence and fewer lynchings than the American South. The Black community in St. Louis was stable and mostly lived near the riverfront or railroad yards. Although informal discrimination in housing had existed since the Civil War, St. Louis passed a residential segregation law only in 1916. This law was quickly stopped by courts. But private agreements in real estate, called restrictive covenants, limited white owners from selling to Black people. This was another form of racial discrimination. In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled these agreements unconstitutional in Shelley v. Kraemer. This case was based on a St. Louis house sale to a Black family.

Despite segregation, St. Louis offered safety during the 1917 East St. Louis Riot. St. Louis police helped Black people fleeing across the Eads Bridge. The city government and the American Red Cross provided shelter and food. Leonidas C. Dyer, a U.S. Representative from St. Louis, led a Congressional investigation into the events. He later proposed an anti-lynching bill. Because of refugees from East St. Louis and the overall Great Migration, the Black population of St. Louis grew much faster than the total population between 1910 and 1920.

World War I and the Great Depression

| 1930 | 1931 | 1933 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| National average | 8.7% | 15.9% | 24.9% |

| St. Louis (total) | 9.8% | 24% | 35% |

| St. Louis (blacks) | 13.2% | 42.8% | 80% |

When World War I started in 1914, both the German and Irish communities in St. Louis wanted the U.S. to stay neutral. This led to more nativism after the U.S. entered the war in 1917. German St. Louisans faced some discrimination, and German culture was suppressed. Business was not greatly affected by the war. However, the population started to decrease as men were needed for factories closer to the Atlantic.

In response to the 1918 influenza pandemic, the Health Commissioner, Dr. Max C. Starkloff, closed all public places in October 1918. He also banned public gatherings of more than 20 people. His actions are seen as an early example of social distancing. St. Louis had half the death rate compared to other cities that did not take such measures.

After World War I, the nationwide prohibition of alcohol in 1919 caused big losses for the St. Louis brewing industry. Other industries, like clothing manufacturing, car making, and chemical production, filled much of the gap. St. Louis's economy was quite diverse and healthy in the 1920s.

St. Louis suffered as much as or more than other cities during the early years of the Great Depression. Factory output fell by 57 percent between 1929 and 1933. Unemployment was high in most cities, and St. Louis was no different (see table). Black workers in St. Louis faced much higher unemployment than white workers. To help the unemployed, the city started giving money for relief operations in 1930. New Deal programs, like the Public Works Administration, also employed thousands of St. Louisans. Construction jobs helped reduce the number of people needing direct relief by the late 1930s.

World War II and Its Aftermath

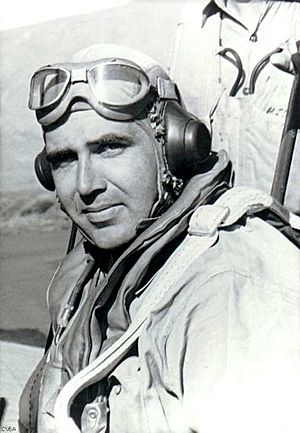

During World War II, St. Louis had a large ammunition factory and the Curtiss-Wright aircraft factory. Area factories also made uniforms, shoes, K-rations, chemicals, and medicines. The uranium used in the Manhattan Project was processed in St. Louis by Mallinckrodt Chemical Company starting in 1942. Several atomic bomb scientists had ties to St. Louis. At the start of the war, many German, Italian, and Japanese St. Louisans were questioned or arrested. The FBI investigated claims of disloyalty in the area. Residents practiced civil defense drills and supported the war effort by collecting scrap and buying war bonds. St. Louis produced several notable soldiers, including Edward O'Hare, who won the Medal of Honor. Wendell O. Pruitt, an African-American pilot, also achieved great success.

At the start of the war, African-American workers gained more acceptance in industry. But discrimination was still a problem. During the war, city officials passed the first city integration law. It allowed African Americans to eat at city-owned lunch counters, but not private ones. In May 1944, a Black sailor in uniform was refused service at a private lunch counter. This led to peaceful sit-in protests at downtown diners. No changes to Jim Crow segregation at lunch counters happened immediately. However, Saint Louis University admitted its first Black students in August 1944.

More than 5,400 St. Louisans were killed or went missing in the war. The end of the war led to many St. Louis factories closing. Major layoffs began in May and continued through August 1945. By late 1945, returning soldiers faced a shortage of housing and jobs. The GI Bill allowed many St. Louis veterans to buy homes and go to college. This encouraged people to move to the suburbs, which reduced the city's population after the war.

Moving to the Suburbs and Population Loss

People moving westward from St. Louis had been happening since the city's early days. But it sped up in the late 1800s. Starting in the 1890s, the St. Louis streetcar system and commuter train stations allowed people to travel from suburban towns into downtown. Towns like Kirkwood, Maplewood, and Webster Groves grew quickly between 1900 and 1930. This movement to these towns doubled the population of St. Louis County from 1910 to 1920. Meanwhile, the city only grew by 12 percent.

In the 1930s, the city's population decreased slightly for the first time. But St. Louis County grew by nearly 30 percent. Almost 80 percent of new homes in the region were built outside city limits in the late 1930s. St. Louis city planners could not stop this by adding more land to the city.

The city reached its highest population in 1950, with 856,796 residents. It peaked in the early 1950s with about 880,000 people. However, new highways and more car ownership allowed even more people to move to the suburbs. The city's population began a long decline. Another reason for the population loss was white flight. This began in the late 1950s and continued through the 1960s and 1970s. From 1950 to 1960, the city population dropped by 13 percent. From 1960 to 1970, it dropped another 17 percent. Most of this decline was white residents moving out, mainly to the suburbs.

Between 1960 and 1970, 34 percent of white city residents moved out. Also, more white people died than were born in the city. By the early 1970s, the white population had decreased significantly, especially among young adults. The Black population of St. Louis grew by 19.5 percent in the 1960s. During that decade, the percentage of Black city residents rose from 29 to 41 percent. However, the Black population also decreased from 1968 to 1972, with many Black residents moving out of the city to suburban areas in St. Louis County.

City Renewal Projects and the Gateway Arch

Early efforts to improve St. Louis happened at the same time as plans to build a riverfront memorial to honor Thomas Jefferson. This memorial would later include the famous Gateway Arch. Work began in the early 1930s to buy and tear down buildings in a forty-block area where the memorial would stand. The only part of the original street grid that remained was north of the Eads Bridge. The only building left in the area was the Old Cathedral. Demolition continued until World War II. After the war, the area was used as a parking lot.

The project stalled until a design competition for the memorial was held. In 1948, Finnish architect Eero Saarinen's design for a tall, curved arch won. However, construction didn't start until 1954. The Arch was completed in October 1965. A museum and visitors' center opened underneath it in 1976. The Arch attracted millions of visitors. It also led to over $500 million in downtown construction in the 1970s and 1980s.

Along with plans for the Gateway Arch, there were plans to build subsidized housing in the city in the 1930s. Despite city improvements in the 1920s and two housing projects built in 1939, many houses after World War II still lacked basic facilities. Thousands of St. Louisans lived in crowded, unsafe conditions.

Starting in 1953, St. Louis cleared the Chestnut Valley area in Midtown. The land was sold to developers who built middle-class apartment buildings. Nearby, the city cleared over 450 acres (1.8 km2) of a neighborhood called Mill Creek Valley. This displaced thousands of people. A mixed-income housing development called LaClede Town was built there in the early 1960s. However, this was later torn down for a Saint Louis University expansion. Most people displaced from Mill Creek Valley were poor and African American. They often moved to stable, middle-class Black neighborhoods like The Ville.

In 1953, St. Louis issued bonds to fund the St. Louis Gateway Mall project and several new high-rise housing projects. The most famous and largest was Pruitt–Igoe. It opened in 1954 on the northwest edge of downtown. It had 33 eleven-story buildings with nearly 3,000 units. Between 1953 and 1957, St. Louis built over 6,100 public housing units. They opened with excitement from leaders, the media, and new residents.

But problems quickly appeared. There was too little recreational space, not enough healthcare or shopping centers, and few job opportunities. Crime was widespread, especially at Pruitt–Igoe. That complex was torn down in 1975. Other St. Louis housing projects remained mostly full through the 1980s, despite ongoing crime problems.

Along with housing projects, a 1955 urban renewal bond issue provided over $110 million. These funds bought land to build three expressways into downtown St. Louis. These later became Interstate 64, Interstate 70, and Interstate 44. In 1967, the Poplar Street Bridge opened. It carried traffic from all three expressways over the Mississippi River. The Arch opened in 1965, and the bridge in 1967. A new stadium for the St. Louis Cardinals also opened. The Cardinals moved into Busch Memorial Stadium in 1966. Building the stadium required tearing down Chinatown, St. Louis, ending the Chinese immigrant community that had been there for decades.

Recent Times: 1981–Present

School Desegregation and Transfers

Even though official segregation in St. Louis public schools ended in 1954, after Brown v. Board of Education, some St. Louis area educators still used tactics to keep schools separated by race in the 1960s.

In the 1970s, a lawsuit challenged this segregation. This led to a 1983 agreement. St. Louis County school districts agreed to accept Black students from the city on a voluntary basis. State money was used to transport students to provide an integrated education. The agreement also asked white students from the county to voluntarily attend city magnet schools. This was an effort to desegregate the city's remaining schools.

Despite opposition from state and local leaders, the plan greatly desegregated St. Louis schools. In 1980, 82 percent of Black students in the city attended all-Black schools. By 1995, only 41 percent did. In the late 1990s, the St. Louis voluntary transfer program was the largest of its kind in the United States. Over 14,000 students were enrolled.

A new agreement in 1999 allowed most St. Louis County districts to continue participating. However, they could reduce the number of incoming transfer students starting in 2002. Districts have been allowed to reduce available seats in the program by five percent each year since 1999. A five-year extension was approved in 2007, and another in 2012. This allowed new students to enroll through the 2018–2019 school year.

Critics say that most of the desegregation happens when Black students transfer to the county, not when white students transfer to the city. Another criticism is that the program weakens city schools by taking away talented students. Despite these issues, the program will continue until all transfer students graduate. With the last group of transfer students allowed to enroll in 2018–2019, the program will end after the 2030–2031 school year.

New Buildings and City Improvements

From 1981 to 1993, new construction projects started downtown. This was the most activity since the early 1960s. One of these was the city's tallest building, One Metropolitan Square, built in 1989. New shopping areas also began to appear. Amtrak stopped using Union Station as a passenger train terminal in 1978. But in 1985, it reopened as a festival marketplace. The same year, developers opened St. Louis Centre, a large four-story shopping mall.

By the late 1990s, however, the mall became less popular. This was due to the expansion of the St. Louis Galleria in Brentwood, Missouri. The mall's main store closed in 2001. The mall itself closed in 2006. Starting in 2010, developers began turning the mall into a parking garage. An adjoining building was converted into apartments, a hotel, and shops.

The city also supported a major expansion of the St. Louis Convention Center in the 1980s. City leaders focused on keeping professional sports teams. To do this, the city bought The Arena. This was a 15,000-seat venue for professional ice hockey, home to the St. Louis Blues. In the early 1990s, leaders worked with businesses to build a new ice hockey arena. This arena, now called the Enterprise Center, was built on the site of the city's Kiel Auditorium. The developers promised to renovate the nearby opera house.

The arena opened in 1994. The original arena was torn down in 1999. But renovations on the opera house didn't start until 2007, more than 15 years later. The Peabody Opera House reopened on October 1, 2011.

In January 1995, the owner of the National Football League team, the Los Angeles Rams, announced they would move to St. Louis. The team replaced the St. Louis Cardinals, an NFL team that had moved to Arizona in 1988. The Rams played their first game in their St. Louis stadium, The Dome at America's Center, on October 22, 1996.

Starting in the early 1980s, more renovation and construction projects began. Some are still unfinished. In 1981, the Fox Theatre, a movie theater that closed in 1978, was fully restored. It reopened as a performing arts venue.

One area that saw major changes was the Washington Avenue Historic District. This area runs along Washington Avenue for almost two dozen blocks. In the early 1990s, clothing manufacturers moved out of the large office buildings there. By the end of that decade, developers began turning the buildings into lofts (apartments). Prices for these spaces increased greatly. By 2001, nearly 280 apartments were built. One project still being developed is the Mercantile Exchange Building. It is being converted into offices, apartments, shops, and a movie theater. These changes have also increased the downtown population. Both the central business district and Washington Avenue district more than doubled their populations from 2000 to 2010.

Other downtown projects include the renovation of the Old Post Office. This started in 1998 and finished in 2006. The Old Post Office and seven nearby buildings had been empty since the early 1990s. By 2010, this complex had various tenants. These included a branch of the St. Louis Public Library, a branch of Webster University, and government offices. The Old Post Office renovation led to the development of a nearby plaza. This plaza is connected to a new $80 million residential building called Roberts Tower. It was the first new residential building in downtown St. Louis since the 1970s.

As early as 1999, the St. Louis Cardinals started pushing for a new Busch Stadium. This was part of a trend in Major League Baseball to build new stadiums. In early 2002, plans for a new park were agreed upon by state and local leaders and the Cardinals owners. The Cardinals agreed to build a mixed-use development called St. Louis Ballpark Village. This would be on part of the old Busch Memorial Stadium site. The new stadium opened in 2006. Construction for Ballpark Village began in February 2013.

St. Louis is known for its architecture. In recent years, there has been a growing movement for historic preservation. An organization called the National Building Arts Center supports this effort.

Images for kids

-

Passenger jam the interior of Union Station in St. Louis, the largest and busiest train station in the world when it opened in 1894.

-

St Patrick's Day procession, 1874