History of science and technology in Africa facts for kids

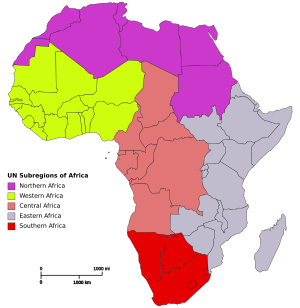

Africa has the world's oldest proof of human inventions. The very first stone tools ever found were in eastern Africa. Later, tools made by early human ancestors were found all over West, Central, Eastern, and Southern Africa. Even though Africa has made amazing progress in math, metalwork, building, and other areas, its history of science and technology hasn't gotten as much attention as other parts of the world.

Contents

- Early Human Tools and Art

- Learning and Schools

- Looking at the Stars: Astronomy

- Working with Numbers: Mathematics

- Working with Metals: Metallurgy

- Healing and Health: Medicine

- Growing Food: Agriculture

- Making Clothes: Textiles

- Moving Around: Maritime Technology

- Building and Design: Architecture

- Sharing Ideas: Communication Systems

- Ways to Travel: Transportation Technologies

- Fighting and Defense: Warfare

- Buying and Selling: Commerce

- Science and African Beliefs

- Recent Scientific Research

- Africa in Science (AiS)

- Science and Technology by Country

- See also

Early Human Tools and Art

The Great Rift Valley in Africa is a very important place for understanding how early humans developed. The oldest tools in the world were found there:

- About 3.3 million years ago, an early human ancestor, possibly Australopithecus afarensis or Kenyanthropus platyops, made stone tools at Lomekwi in eastern Africa.

- Homo habilis, who lived in eastern Africa, created another early tool style called the Oldowan about 2.3 million years ago.

- Homo erectus developed the Acheulean stone tool style, which included hand-axes, about 1.5 million years ago. This tool style spread to the Middle East and Europe. Homo erectus also started using fire.

- Homo sapiens, or modern humans, made bone tools and sharp blades about 90,000 to 60,000 years ago in southern and eastern Africa. These tools became common in later Stone Age times.

The first abstract art also appeared during the Middle Stone Age. The oldest abstract art in the world is a shell necklace from the Cave of Pigeons in Taforalt, eastern Morocco, dated to 82,000 years ago. The second oldest abstract art and the oldest rock art was found at Blombos Cave in South Africa, dated to 77,000 years ago. There is also evidence that Stone Age humans in Southern Africa had basic chemistry knowledge about 100,000 years ago. They used a special recipe to make a liquid mixture rich in ochre.

Learning and Schools

Learning in Northern Africa and the Nile Valley

The Library of Alexandria was founded in Egypt in 295 BC. It was the biggest library in the ancient world.

Al-Azhar University, started around 970-972 as a religious school called a madrasa, is a major center for Arabic and Islamic studies. It began granting degrees in 1961 when it added non-religious subjects.

Learning in West Africa and the Sahel

From the 14th to the 16th centuries, Mali had three important Islamic schools in Timbuktu: Sankore Madrasah, Sidi Yahya Mosque, and Djinguereber Mosque. These schools had individual teachers who taught small groups. Libraries were made up of private collections of books. Scholars came from rich families, and the main subjects were religious studies, Arabic, and law.

In the 16th century, Timbuktu also had many smaller schools called maktabs. These taught basic reading and reciting of the Qur’an. About 4,000 to 5,000 students attended these schools.

Timbuktu was a big center for copying books, religious groups, Islamic sciences, and arts in West Africa. Books were brought in from North Africa, and paper came from Europe. Most books were written in Arabic.

The most famous scholar from Timbuktu was Ahmad Baba (1556–1627). He mostly wrote about Islamic law.

Looking at the Stars: Astronomy

Africa has three types of calendars: lunar (based on the moon), solar (based on the sun), and stellar (based on stars). Most African calendars combine these. Examples include the Akan, Egyptian, Berber, and Ethiopian calendars.

Astronomy in Northern Africa and the Nile Valley

A stone circle at Nabta Playa might be one of the world's oldest tools for studying stars. Built by ancient Nubians around 4800 BCE, it may have marked the summer solstice.

Ancient Egyptians likely used stars to align their pyramids. They might have watched two stars in the Plough / Big Dipper constellation. By lining up these stars with a plumb bob, they could find true North.

Egyptians were the first to create a 365-day, 12-month calendar. It was a stellar calendar, based on observing stars.

In the 12th century, the astrolabic quadrant, a tool for measuring star positions, was invented in Egypt.

Astronomy in West Africa and the Sahel

Timbuktu manuscripts from the 14th–16th centuries show that astronomers there:

- Used the Julian Calendar.

- Generally believed the sun was the center of the Solar System (a heliocentric view).

- Drew diagrams of planets and orbits with math.

- Could accurately find the direction to Mecca for prayer.

- Recorded events like a meteor shower in August 1583.

Mali also had astronomers, including the emperor and scientist Askia Mohammad I.

Astronomy in Eastern Africa

Large stone pillars called "namoratunga" near Lake Turkana in Kenya date back 5,000 years. Some believe they were used by Cushitic people to align with star systems for a lunar calendar.

Astronomy in Southern Africa

Today, South Africa has a growing astronomy community. It hosts the Southern African Large Telescope, the biggest optical telescope in the southern hemisphere. South Africa is also building the Karoo Array Telescope for the huge $20 billion Square Kilometer Array project.

Archaeological finds suggest that ancient kingdoms in Zimbabwe, like Great Zimbabwe, used astronomy. Monolith stones with special carvings, thought to track Venus, were found.

Working with Numbers: Mathematics

Rock paintings and carvings across Africa show geometric shapes. Other finds like stone tools, metal tools, and pottery also show an understanding of geometry. Finds from the Tellem people, like baskets and wooden objects, are very important. They show early geometric exploration. The oldest buildings in the Tellem caves are cylindrical granaries made of mud, dating from the 3rd to 2nd century BC.

Mathematics in Central and Southern Africa

The Lebombo bone from the mountains between Swaziland and South Africa might be the oldest known mathematical object. It's 35,000 years old and has 29 notches cut into a baboon's leg bone.

The Ishango bone is a bone tool from the Democratic Republic of Congo, about 18,000 to 20,000 years old. It's also a baboon's leg bone with a sharp quartz piece. It was first thought to be a tally stick, but some scientists think the notches show a deeper understanding of math, possibly for multiplication, division, or even as a lunar calendar.

The Bushong people can tell which graphs can be drawn without lifting your pen or retracing lines (called Eulerian paths). They use these graphs for things like embroidery. In 1905, a European expert noted that Bushong children knew how to solve these problems easily.

The "sona" drawing tradition of Angola also shows mathematical ideas.

In 1982, Rebecca Walo Omana became the first female math professor in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Mathematics in Northern Africa and the Nile Valley

By the ancient Naqada period in Egypt, people had a fully developed numeral system. Texts like the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus show that ancient Egyptians could do basic math operations (add, subtract, multiply, divide), use fractions, and calculate areas and volumes. They understood basic algebra and geometry.

Their number system was based on tens, using hieroglyphic signs for each power of ten up to one million. They wrote fractions as sums of smaller fractions, for example, two-fifths as one-third plus one-fifteenth.

Ancient Egyptian mathematicians understood the ideas behind the Pythagorean theorem. They knew that a triangle with sides in a 3–4–5 ratio had a right angle. They could estimate the area of a circle by subtracting one-ninth from its diameter and squaring the result. This was a good guess for the formula πr2.

The golden ratio seems to appear in many Egyptian buildings, like the pyramids. This might have happened naturally because they combined knotted ropes with a good sense of proportion.

Plans of Meroitic King Amanikhabali's pyramids show that Nubians had a good understanding of math and harmonic ratios.

Working with Metals: Metallurgy

Most of Africa moved from the Stone Age directly to the Iron Age. The Iron Age and Bronze Age happened at the same time in some places. North Africa and the Nile Valley got their iron technology from the Near East.

Many experts believe that iron use developed independently south of the Sahara. The earliest iron found outside North Africa is from 2500 BCE at Egaro. Another accepted date is 1500 BCE at Termit. Iron use for tools appeared in West Africa by 1200 BCE, making it one of the first places to enter the Iron Age. Before the 19th century, African ways of getting iron were even used in Brazil.

Historian John K. Thornton believes that African metalworkers were as productive as, or even more productive than, their European counterparts.

Scientific studies show that metal technology started in many parts of Africa: West Africa, Central Africa, and East Africa. This means these developments were native African technologies. Iron metalwork happened in Nigeria around 2631-2458 BCE, in Central Africa Republic around 2136-1921 BCE, in Niger around 1895-1370 BCE, and in Togo around 1297-1051 BCE.

Metalwork in West Africa

Africans were skilled in working with iron, brass, and bronze. Ife made realistic brass statues starting in the 13th century. Benin mastered bronze in the 16th century, creating portraits and reliefs using the lost wax process. Benin also made glass and glass beads.

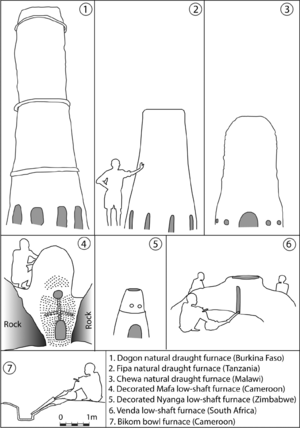

In West Africa, several places started producing iron using natural draft furnaces around 1000 AD. For example, iron production in Banjeli and Bassar in Togo was very high. In Burkina Faso, the Korsimoro district also produced a lot of iron.

Brass barrel blunderbusses were made in some Gold Coast states in the 18th and 19th centuries. Asante blacksmiths could repair firearms and even remake parts like barrels.

In the Aïr Mountains of Niger, copper smelting developed independently between 3000 and 2500 BCE. The simple way it was done suggests it wasn't from a foreign source. It became more advanced around 1500 BCE.

Metalwork in the Sahel

Africa was a major supplier of gold in world trade during the Middle Ages. The Sahelian empires became powerful by controlling the Trans-Saharan trade routes. They provided two-thirds of the gold to Europe and North Africa. Gold from the Sahelian empires was used to make coins in Europe and the Islamic world.

Swahili traders in East Africa supplied a lot of gold to Asia through the Red Sea and Indian Ocean trade routes. The trading cities of the Swahili coast were among the first African cities to meet European explorers. Many were described by the North African explorer Abu Muhammad ibn Battuta.

Metalwork in Northern Africa and the Nile Valley

Nubia was a major source of gold in the ancient world. Gold was a big reason for Kushitic wealth and power. Gold was mined east of the Nile.

Around 500 BCE, Nubia, during the Meroitic phase, became a major maker and exporter of iron. This happened after they were forced out of Egypt by the Assyrians, who used iron weapons.

Metalwork in East Africa

The Aksumites made coins around 270 CE, under King Endubis. Aksumite coins were made of gold, silver, and bronze.

Since 500 BC, people in Uganda had been making high-quality carbon steels using special furnaces. This technique was only achieved in Europe much later. Anthropologist Peter Schmidt found that the Haya in Tanzania have been making steel for about 2000 years.

Two types of iron furnaces were used in most of Africa: trenches dug underground and circular clay structures built above ground. Iron ores were crushed and put in furnaces with layers of hardwood. Bellows were used to add oxygen, and clay pipes called tuyères controlled the airflow.

Metalwork in Central Africa

Two examples show how skilled Kongo metalworkers were. A Portuguese effort to build an iron foundry in Angola in the 1750s failed to compete with Kongo blacksmiths. The iron made by Kongo smiths was better than European imports. European iron often contained sulfur and was less durable than the high-carbon steel made by Kongo processes.

Over time, deforestation made it harder to get charcoal for smelting iron from ore. This led to more use of pre-forged European iron bars. Wars in the Kingdom of Kongo also disrupted iron production. Many Kongo people were sold as slaves, and their skills became very valuable in the New World as blacksmiths and ironworkers.

At Oboui, an iron forge was found with dates around 2000 BCE. This might make Oboui the oldest iron-working site in the world.

Healing and Health: Medicine

Traditional African plants like Ouabain, capsicum, ginger, and Kola nut are still used by Western doctors today.

Medicine in West Africa and the Sahel

West Africans, especially the Akan, knew how to vaccinate against smallpox. A slave named Onesimus taught this method to Cotton Mather in the 18th century.

Bonesetting is practiced by many groups in West Africa, including the Akan, Mano, and Yoruba.

In Djenné, people knew that mosquitoes caused malaria. Removing cataracts was also a common surgery. Timbuktu manuscripts show that African Muslim scholars knew about the dangers of smoking tobacco.

Palm oil was important for health and hygiene. People used it to protect their skin and hair. Many Africans saw palm oil as a medicine itself, mixing it with herbs to treat skin problems or headaches. Foreign visitors praised the quality of soap made from palm oil.

During the Atlantic slave trade, European sailors saw African slaves recover from diseases like smallpox using their traditional medicine, which included palm oil.

Medicine in Northern Africa and the Nile Valley

Ancient Egyptian doctors were famous for their healing skills. Some, like Imhotep, were known long after they died. They had specialized doctors for different body parts, like eye doctors and dentists. Medical texts show they had practical knowledge of anatomy and injuries. Wounds were treated with bandages, honey to prevent infection, and stitches. Garlic and onions were used for good health and to help with asthma. Surgeons stitched wounds, set broken bones, and amputated limbs.

Around 800 AD, the first psychiatric hospital was built in Cairo by Muslim doctors.

In 1285, the largest hospital of the Middle Ages was built in Cairo by Sultan Qalaun al-Mansur. Treatment was free for everyone, no matter their background.

Tetracycline, an antibiotic, was used by Nubians between 350 AD and 550 AD. This was found in bone remains. It's thought that earthen jars used for making beer contained bacteria that produced tetracycline. Nubians likely didn't know about the antibiotic itself, but noticed people felt better after drinking the beer.

Medicine in East Africa

European travelers in the Great Lakes region in the 19th century reported advanced surgery in the kingdom of Bunyoro-Kitara. Medical historians say Bunyoro's healers were very skilled. Caesarean sections and other operations were performed using antiseptics, anesthetics, and cautery irons. Patients were given banana wine to numb pain, and herbal mixtures helped healing.

Bunyoro surgeons had good knowledge of anatomy, partly from doing autopsies. They treated war wounds and even performed brain surgery. Vaccination against smallpox and measles was also done. Over 200 plants were used for medicine.

Barkcloth, used for bandages, has been shown to kill germs.

Medicine in Central Africa

General and local anesthesia were widely used by traditional doctors in Central Africa. Beer with kaffir extract was given for deep wounds to ease pain. Leaves with alkaloids were applied to injuries. Many tribes performed cataract surgery under local anesthesia, using plant juices to numb the eyes.

Medicine in Southern Africa

A South African, Max Theiler, developed a vaccine against yellow fever in 1937. Allan McLeod Cormack helped invent the CT-scanner.

The first human heart transplant was done by South African surgeon Christiaan Barnard in December 1967.

During the 1960s, South African Aaron Klug developed ways to use electron microscopy to create 3D images of crystals.

The Zulu king was like the ultimate public health official. He and his chiefs were responsible for their people's well-being. They had many doctors to help. If someone got very sick, it would be reported up to the king. The king might send his own doctors or medicines. The Zulu state even banned a whitish metal that was linked to unexplained deaths.

Bone-setting was common in Southern Africa. Even broken fingers were treated. Abdominal wounds were also treated successfully.

Growing Food: Agriculture

Tropical soils often have low organic matter, which makes farming difficult. Farmers often use fields for a few years, then let them rest for a decade or more to restore the soil.

Africans carefully observed, experimented, and selected desirable traits in bananas and plantains for 2,000 years. This led to a huge variety of types (120 plantains, 60 bananas). This shows the great farming skills Africans had before Europeans arrived.

Like people in the Amazon, Africans also created dark, fertile soils similar to Terra preta.

Agriculture in Northern Africa and the Nile Valley

Archaeologists have debated whether cattle were first domesticated in Africa. Possible remains of domesticated cattle were found in Egypt dating to 9500–8000 BP. However, genetic evidence suggests cattle were likely brought from Southwest Asia.

Genetic evidence also shows that donkeys were domesticated from the African wild ass. Donkey burials in Egypt from around 5000 BP show they were used as pack animals.

Cotton may have been domesticated around 5000 BCE in eastern Sudan, where cotton cloth was produced.

Agriculture in East Africa

Finger millet is from the highlands of East Africa and was domesticated before 3000 BCE in Uganda and Ethiopia.

Engaruka in Tanzania is an Iron Age site with a complex irrigation system. Stone channels were used to control river water and irrigate about 5000 acres of land.

The Shilluk Kingdom in Sudan had an economy based on cereal farming and fishing. The Shilluk developed very intensive farming of Sorghum and Millet. By the 1600s, their land had a population density similar to or even higher than the Egyptian Nile lands.

Ethiopians, especially the Oromo people, were the first to discover and recognize the energizing effect of the coffee bean plant.

Ox-drawn plows have been used in Ethiopia for two millennia, possibly longer.

Teff, Noog, and ensete are other plants domesticated in Ethiopia.

Ethiopians used terraced hillsides to prevent erosion and for irrigation. A 19th-century European described the terraced mountains in an Abyssinian valley as vast and carefully cultivated.

In the African Great Lakes, advanced farming practices included irrigation in mountains, man-made watering places, river diversions, and extensive use of terraces. They also practiced double and triple cropping. Foreign experts were impressed by their sophisticated methods of intensive farming.

The earliest Europeans in Rwanda saw great pride in farming skills. Mothers gave crying babies toy hoes. Rwandan farmers used manure, terracing, and artificial irrigation, often better than Eastern European peasants.

The Chaga people have long practiced advanced agriculture, controlling and distributing water. Europeans praised their irrigation works and social organization.

Agriculture in West Africa and the Sahel

The earliest evidence for plant domestication in Africa is in the Sahel region around 5000 BCE. This is when sorghum and African rice began to be grown. Other African domesticated plants include oil palm, African yam, black-eyed peas, and kola nuts.

Studies in the Upper Guinea forest found links between palm oil processing, "sacred agroforests," and rich, dark soils. Palm oil production pits helped create these fertile soils. These areas became diverse groves of palms and other forest species.

African oil palms were common in the oil palm-yam farming areas. Farmers protected and managed palms within their plots of yams, cocoyams, and other crops. This "slash-and-burn" method, though criticized, has been shown to be effective. It led to more plant and animal diversity, food security, and balanced diets. Oil palm agroforests provided fats and vitamins, which were especially important where tsetse flies made raising livestock difficult.

African methods of growing rice, brought by enslaved Africans, may have been used in North Carolina. This might have helped the colony's success. Portuguese observers in the 15th and 16th centuries admired the intensive rice-growing techniques in the Upper Guinea Coast.

Yams were domesticated 8000 BCE in West Africa. Between 7000 and 5000 BCE, pearl millet, gourds, watermelons, and beans also spread across the southern Sahara.

Between 6500 and 3500 BCE, knowledge of domesticated sorghum, castor beans, and two gourd species spread from Africa to Asia. Other crops like pearl millet and okra later spread worldwide.

Intensive terrace farming was likely practiced in West Africa before the early 15th century AD. Many groups, like the Mafa and Dogon, used terraces.

Agriculture in Southern Africa

To prevent erosion, Southern Africans built dry-stone terraces on steep hillsides.

Randall Maclver described the irrigation technology at Nyanga, Zimbabwe. Streams were tapped near their source, and water was diverted into high-level channels that ran for miles. The gradients were calculated very skillfully.

Cattle were a main source of food and power in Southern Africa. Sotho, Tswana, and Nguni kingdoms grew strong with successful cattle keeping.

Cattle played a central role in Nguni culture. The Zulu king Shaka Zulu's royal cattle pen had 7,000 pure white Nguni cattle. Early pioneers in Zimbabwe reported the country was full of healthy cattle.

South Africans were known for being experts at finding lost cattle. A single Zulu person could find 10 cattle lost two years earlier over a large area.

The Himba people have incredibly sharp vision, believed to come from their need to identify each cow's markings.

Agriculture in Central Africa

Scientists once thought Africa's first farmers destroyed rainforests. However, new research shows that a dry period 4,000-5,000 years ago caused forests to shrink and grasslands to spread. Oil palms likely grew in these new open areas, with seeds spread by animals. Humans then helped the palms by protecting them from fires and elephants.

Linguistic evidence shows a strong link between oil palm spread and the arrival of Bantu-speaking farmers in the Congo basin around 1000 BC. This suggests the trees came with the migrants. A tradition among Mfumte-speakers in Cameroon says oil palms "follow men," growing where humans have been active.

Instead of destroying forests, African farmers may have actually helped grow them in many places. Ethnographic research shows that forests grew from the rich, moist soils left in the shade of abandoned village palm groves. These "emergent" groves are not purely human creations but develop from human interaction with nature.

As early as the 1920s, elders in Congo told a missionary that they were not "shifting cultivators" cutting down forests; they had built the forest with their farming practices. This shows the versatility, ingenuity, and sustainability of local farming practices.

Making Clothes: Textiles

Textiles in Northern Africa

Egyptians wore linen from the flax plant and used looms as early as 4000 BCE. Nubians mainly wore cotton, beaded leather, and linen. The Djellaba was typically made of wool and worn in the Maghreb.

Textiles in West Africa and the Sahel

Early travelers praised the high quality of Mandinka cotton cloth found along the West African coast. Similar comments were made about cotton cloth from the "Slave Coast" and Benin.

Some of the oldest surviving African textiles were found at Kissi in northern Burkina Faso. They are made of wool or fine animal hair. Textile fragments from the 13th century were also found in Benin City, Nigeria.

In the Sahel, cotton is widely used to make the boubou (for men) and kaftan (for women).

Bògòlanfini (mudcloth) is a cotton fabric dyed with fermented mud, made by the Bambara people of central Mali.

By the 12th century, "Moroccan leather," which actually came from the Hausa area of northern Nigeria, was sold in Mediterranean markets and reached Europe.

Kente cloth was made by the Akan people (Ashante, Fante, Enzema) and Ewe people in Togo, Ghana, and Côte d'Ivoire.

From the 11th to the 15th century, the Tellem people buried their dead with well-preserved objects like woolen and cotton blankets. Experts found that Tellem textiles were high quality and had a great variety of patterns using only indigo dye. Weavers experimented with patterns and understood how different thread arrangements affected the designs.

Textiles in Central Africa

Among the Kuba people in the Democratic Republic of Congo, clothes were woven from raffia palm leaves.

Weaving with palm leaves was a highly developed art in Central Africa. European travelers compared woven palm-leaf cloth to the finest European silks. One traveler praised the "marvelous art" of making cloths like velvets and satins from palm leaves. The finest pieces were so "precious" that only the king and those he favored could wear them.

Historian John K. Thornton argues that African textile manufacturing was much more advanced than often recognized. Large amounts of textiles were produced. For example, Momboares in eastern Congo produced 400,000 meters of cloth per year in the early 17th century, compared to 100,000 meters in Leiden, a leading European textile center. These products were traded widely within Africa and exported to the Caribbean and South America.

Textiles in East Africa

Barkcloth was used by the Baganda in Uganda from the Mutuba tree. Kanga are rectangular cotton fabrics worn by the Swahili. Kitenge are similar but thicker.

Shemma, shama, and kuta are cotton cloths used for Ethiopian clothing. Three types of looms are used in Africa: the double heddle loom, the single heddle loom, and the ground or pit loom. The first two might be of African origin.

Textiles in Southern Africa

In Southern Africa, animal hides and skins were widely used for clothing. The Ndau and Shona mixed hide with barkcloth and cotton. Cotton weaving was also practiced. The Venda, Swazi, Basotho, Zulu, Ndebele, and Xhosa also used hides from cattle, sheep, goats, and leopards. Leopard skins were a symbol of kingship for the Zulu. Skins were tanned, dyed, and decorated with beads.

Moving Around: Maritime Technology

In 1987, the Dufuna canoe was found in Nigeria. It is the third oldest canoe in the world and the oldest in Africa, dating back about 8000 years. It was made from African mahogany.

Maritime Technology in Northern Africa and the Nile Valley

Carthage had many warships, including quadriremes and quinqueremes (ships with four and five rows of rowers). Their ships ruled the Mediterranean Sea.

Early Egyptians knew how to build planks of wood into a ship hull as early as 3000 BC. The oldest ships found, a group of 14 in Abydos, were made of wooden planks "sewn" together with woven straps. Reeds or grass were stuffed between the planks to seal them.

Early Egyptians also knew how to fasten planks with wooden pegs and use pitch to seal the seams. The "Khufu ship", a 43.6-meter vessel from around 2500 BCE, is a full-size example. They also used mortise and tenon joints to connect planks.

Maritime Technology in West Africa and the Sahel

A Nok sculpture shows two people and their goods in a dugout canoe. This suggests Nok people used canoes to transport cargo along rivers like the Gurara River and traded them. The seashell on one figure's head might mean trade routes reached the Atlantic Coast.

In the 14th century CE, King Abubakari II of the Mali Empire was said to have many boats on the West African coast. Malian boats were canoes of different sizes.

Many sources confirm that West Africa's inland waterways had many war-canoes and transport vessels. Most were made from a single large tree trunk. They were mainly moved by paddles or poles in shallow water. Sails were also used on trading vessels.

Some canoes were 80 feet long and could carry 100 men or more. Documents from 1506 mention war-canoes on the Sierra Leone river carrying 120 men. Other accounts describe canoes 70 feet long and 7-8 feet wide, with sharp ends, rowing benches, and even cooking hearths.

The way West African dugout canoes were built allowed them to travel through the connected river systems of the Benue River, Gambia River, Niger River, and Senegal River, as well as Lake Chad. This system connected different water sources and ecological zones, allowing people, information, and goods to be transported. West African canoers had great skill in navigating these rivers. The sacredness of canoe-making is shown in a proverb: "The blood of kings and the tears of the canoe-maker are sacred things which must not touch the ground."

In 1735 CE, John Atkins observed: "Canoos are what used through the whole Coast for transporting Men and Goods." West African dugout canoes were faster and more maneuverable than European rowboats.

Between the 17th and 18th centuries CE, Takoradi in Ghana was a major center for making dugout canoes that could carry up to eight tons.

West Africans and western Central Africans independently developed the skill of surfing. Accounts from the 17th to 19th centuries describe children and fishermen surfing on boards or small dugouts.

Maritime Technology in East Africa

Ancient Axum traded with India. There is evidence that ships from Northeast Africa sailed between India/Sri Lanka and Nubia, and even to Persia and Rome. Aksum was known to the Greeks for its seaports. The Periplus of the Red Sea reports that Somalis traded frankincense and other items with the Arabian Peninsula and Roman-controlled Egypt.

Middle Age Swahili kingdoms had trade port islands and routes with the Islamic world and Asia. Cities like Mombasa, Zanzibar, and Kilwa were known to Chinese sailors like Zheng He and Islamic historians like Abu Abdullah ibn Battuta. The dhow was the trade ship used by the Swahili. Some were massive, like the one that carried a giraffe to the Chinese Emperor Yong Le's court in 1414.

Few kingdoms south of the Sahara had a more developed navy than Buganda. Its navy had up to 20,000 men and war canoes as long as 72 feet, dominating Lake victoria.

Building and Design: Architecture

Architecture in West Africa

The Walls of Benin City are a huge man-made structure. They stretch for about 16,000 kilometers in total, covering 6500 square kilometers. They were built by the Edo people and are four times longer than the Great Wall of China.

Sungbo's Eredo is the second largest pre-colonial monument in Africa, bigger than the Great Pyramids. It was built by the Yoruba people in honor of a noblewoman named Oloye Bilikisu Sungbo. It consists of large earth walls and valleys around Ijebu-Ode in Nigeria.

Tichit is the oldest surviving stone settlement south of the Sahara. It is thought to have been built by the Soninke people.

The Great Mosque of Djenné is the largest mud-brick building in the world. It is considered a great example of Sudano-Sahelian architecture.

Architecture in Northern Africa and the Nile Valley

Around 1000 AD, cob (tabya), a type of earth construction, first appeared in the Maghreb.

The Egyptian step pyramid at Saqqara is the oldest major stone building in the world.

The Great Pyramid was the tallest man-made structure for over 3,800 years.

The earliest Nubian architecture included the speos, structures carved out of solid rock. Sudan, the site of ancient Nubia, has more pyramids than anywhere else in the world, with 223 pyramids.

Around 1100, the ventilator was invented in Egypt.

Architecture in East Africa

Aksumites built with stone. They created monolithic stelae (large stone slabs) on top of kings' graves. Later, during the Zagwe dynasty, churches like Church of Saint George at Lalibela were carved out of solid rock.

Thimlich Ohinga, a World Heritage Site, is a complex of stone ruins in Kenya.

Architecture in Southern Africa

Southern Africa has ancient traditions of building with stone. Two main styles are the Zimbabwean style (seen at Great Zimbabwe and Khami) and the Transvaal Free State style.

The Tswana people lived in city-states with stone walls and complex social structures built in the 1300s or earlier. These cities had populations of up to 20,000 people.

Sharing Ideas: Communication Systems

Griots are like living history books in African societies without written languages. They can recite family histories going back centuries and tell epic stories about past events.

Communication in Northern Africa and the Nile Valley

Africa's first writing system and the beginning of the alphabet was Egyptian hieroglyphs. Two scripts came directly from Egyptian hieroglyphs: the Proto-Sinaitic script and the Meroitic alphabet. From Proto-Sinaitic came the South Arabian alphabet and Phoenician alphabet, which then led to many other alphabets like Arabic and Greek.

From the South Arabian alphabet came the Ge'ez alphabet, used in Ethiopia and Eritrea for languages like Amharic.

From the Phoenician Alphabet came tifinagh, the Berber alphabet used by the Tuaregs.

The Meroitic alphabet developed from Egyptian hieroglyphs in Nubia. It was fully developed in the 2nd century. The script can be read, but its meaning is not fully understood yet.

Communication in the Sahel

With the arrival of Islam, the Arabic alphabet spread in the Sahel. Arabic writing is common there. The Arabic script was also used to write native African languages, called Ajami.

Communication in West Africa

N'Ko script was developed by Solomana Kante in 1949 for the Mande languages of West Africa. It is used in Guinea, Côte d'Ivoire, Mali, and nearby countries.

Nsibidi is a set of symbols developed by the Ekoi people of Nigeria for communication. Only members of a secret society fully understand its complex use.

Adinkra is a set of symbols from the Akan people (Ghana and Cote d'Ivoire). They represent concepts and sayings.

The Vai syllabary is a writing system for the Vai language, created in Liberia in the 1830s.

Usman dan Fodio greatly increased literacy in the Sokoto Caliphate. By his death, male literacy was about 96-97%, and female literacy was 93-95%. A British traveler noted that people in Sokoto "were literate not to a man, but to a woman."

Communication in Central Africa

In eastern Angola and northwestern Zambia, sona ideographs were used to record knowledge and culture. These drawings show ideas about space and time. They are like a code, similar to how computers process information.

Lukasa memory boards were also used by the BaLuba to store information.

Talking drums use the tones of African languages to send complex messages. They can send messages 15 to 25 miles. In a Bulu village, each person had a unique drum signature. A message could be sent to someone by drumming their signature. Messages could travel 100 miles from village to village in two hours or less using talking drums.

Communication in East Africa

On the Swahili coast, the Swahili language was written in Arabic script, as was the Malagasy language in Madagascar.

The people of Uganda developed a form of writing based on a floral code. Talking drums were also widely used.

The ancient court music composers of Buganda discovered how human hearing processes complex sounds. They used this to create music with interwoven melodies that could suggest words to a Luganda speaker. This is one of the oldest examples of an audio-psychological effect called auditory streaming being used in music.

The Agikuyu of Kenya used a pictographic device called Gicandi to record and spread knowledge. This device used simplified pictures to record events or help a medicine-man remember formulas. A Kikuyu person could also track their cattle's history by notches on a stick. The word for letters or numerals in Kikuyu, ndemwa, means "those that have been cut."

Ways to Travel: Transportation Technologies

Transportation in North Africa

The wheel may have been known in ancient Egypt since the 5th Dynasty. The earliest wheeled transport appeared in ancient Egypt during the 13th Dynasty.

The potter's wheel was brought to ancient Nubia by ancient Egypt. A potter's wheelhead from 1850 BCE was found at Askut.

Since the Meroe period, ox-powered water wheels (like saqiya) and shadufs were used in Nubia.

Between 3200 BP and 1000 BP, rock art in the Central Sahara shows chariots pulled by horses and sometimes cattle. These images were likely made by the Garamantes, ancestors of ancient Berbers.

In the 5th century BCE, Herodotus reported chariots used by the Garamantes in the Sahara.

By the 4th century BCE, the water wheel (especially the noria and sakia) was created in ancient Egypt.

Transportation in West Africa

Rock art at Dhar Tichitt shows a human figure with yoked oxen pulling a cart. Other rock art at Bled Initi shows ox carts from around 650-380 BCE.

In 1670 CE, the king of Allada received a gilded carriage from the French. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Europeans reported seeing wheeled transports like carriages in ceremonies in the kingdom of Dahomey.

In 1824 CE, the king of Lagos gave a large carriage to the emperor of Brazil. By the 1840s CE, King Eyamba V of Old Calabar had two horse-drawn carriages.

Transportation in Southern Africa

At Tsodilo Hills in Botswana, white painted rock art may show a wagon and wagon wheel.

Fighting and Defense: Warfare

Most of tropical Africa did not have cavalry because horses were affected by tse-tse flies, and zebras could not be domesticated. Armies mainly consisted of infantry (foot soldiers). Weapons included bows and arrows (often with poison tips), throwing knives, spears, swords, and heavy clubs. Shields were also widely used. Later, guns like muskets were introduced.

Warfare in West Africa

Fortifications were a major part of defense. Huge earthworks were built around cities in West Africa, like the Walls of Benin and Sungbo's Eredo. These were often defended by soldiers with bows and poison-tipped arrows.

African infantry included women. The state of Dahomey had all-female units called the Dahomey Amazons, who were the king's bodyguards. The Queen Mother of Benin also had her own army.

Biological weapons were used, mostly as poisoned arrows. They also used powders spread on the battlefield or poisoned water supplies. In Borgu, special mixtures were made to kill, hypnotize, or act as antidotes.

Warfare in Northern Africa, Nile Valley, and the Sahel

Ancient Egyptian weapons included bows and arrows, maces, clubs, swords, shields, and knives. Body armor was made of leather with copper scales. Horse-drawn chariots carried archers into battle. Weapons were first made of stone, wood, and copper, then bronze, and later iron.

In 1260, the first portable hand cannons were used by Egyptians to fight the Mongols at the Battle of Ain Jalut. These cannons used explosive gunpowder almost identical to modern gunpowder. Egyptians also used dissolved talc for fire protection and wore fireproof clothing with gunpowder cartridges attached.

Aksumite weapons were mainly iron spears, swords, and knives. Shields were made of buffalo hide. In the late 19th century, Ethiopia modernized its army with repeating rifles, artillery, and machine guns. This helped them win against the Italians at the 1896 Battle of Adwa.

The Sahelian military had cavalry and infantry. Cavalry soldiers were shielded and mounted. Body armor was chain mail or heavy quilted cotton. Helmets were made of leather or animal hide. Weapons included swords, lances, and broad-bladed spears. Infantry used bows and iron-tipped arrows, often laced with poison. Later, muskets were introduced.

Warfare in Southern Africa

In the 1800s, the Afrikaner "kommando" system emerged. These were mounted light infantry units called up from the male population. They saw action in the Xhosa Wars and the Boer Wars. This system became the origin of the modern commando elite light infantry.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, South Africa researched weapons of mass destruction, including nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons. Six nuclear weapons were built. In the 1990s, South Africa voluntarily dismantled all its nuclear weapons, becoming the first nation to give up nuclear arms it had developed.

Buying and Selling: Commerce

Many metal objects and other items were used as money in Africa. These included cowrie shells, salt, gold (dust or solid), copper, iron chains, and cloth. Copper was as valuable as gold in Africa because it was less common, except in Central Africa. Salt was also very valuable due to its scarcity.

Commerce in Northern Africa and the Nile Valley

Carthage imported gold, copper, ivory, and slaves from tropical Africa. It exported salt, cloth, and metal goods. Before camels were widely used in trans-Saharan trade, oxen, donkeys, mules, and horses were used. Camels became common in the 1st century CE. Carthage minted gold, silver, bronze, and electrum coins, mainly to pay its mercenary armies.

Islamic North Africa used gold coins like the Almoravid dinar and Fatimid dinar. These coins were made from gold from the Sahelian empires. European coins like the ducat and florine were also made from this gold.

Ancient Egypt imported ivory, gold, incense, hardwood, and ostrich feathers.

Nubia exported gold, cotton, ostrich feathers, leopard skins, ivory, ebony, and iron.

Commerce in West Africa and the Sahel

Cowries have been used as money in West Africa since the 11th century. Their use spread inland. In some areas, the king's revenue was collected in cowrie shells. Cowries were used in remote parts of Africa until the early 20th century.

The Ghana Empire, Mali Empire, and Songhay Empire were major exporters of gold, iron, and slaves. They imported salt, horses, and other goods. These empires greatly influenced world economics because they controlled 80% of the world's gold, which Europe and the Islamic world depended on. European states even borrowed from African states.

Some currencies in the Sahel included paper debt (IOUs) for long-distance trade, gold coins, and gold dust. Square cloth called chigguiya was also used as currency. In Kanem, cloth was the main currency.

The Akan people used gold weights called "Sika-yôbwê" (stone of gold) as their currency. They had a system of 11 units for computing weight.

Commerce in East Africa

Aksum exported ivory, glass, brass, copper, myrrh, and frankincense. They imported silver, gold, olive oil, and wine. Aksumites made coins of gold, silver, and bronze around 270 CE.

The Swahili acted as middlemen, connecting African goods to Asian markets and Asian goods to African markets. Their most popular export was ivory. They also exported gold, leopard skins, and tortoise shells. They imported pottery and glassware from Asia and manufactured items like cotton and beads. The Swahili also minted silver and copper coins.

Science and African Beliefs

Some people in the West see science as separate from rituals. But in Africa, science is often connected to spiritual beliefs. For example, in the Ile-Ife pantheon, Olokun, the goddess of wealth, is seen as the patron of the glass industry. People would consult her and offer sacrifices for successful work. The same was true for ironworking. Modern studies show how much ancient Africa contributed to global science and technology.

Recent Scientific Research

Ahmed Zewail won the 1999 Nobel Prize in chemistry. He studied very fast changes in chemical reactions, measured in femtoseconds (extremely short seconds).

The Democratic Republic of the Congo has a rocketry program called Troposphere.

Currently, 40% of African-born scientists live in OCED countries, mainly NATO and EU countries. This is called an African brain drain.

Sub-Saharan African countries spent about 0.3% of their GDP on Science and Technology in 2007. This was an increase from previous years. North African countries spent about 0.4% of GDP on research. South Africa spends more, at 0.87% of GDP.

While technology parks have a long history in the US and Europe, they are still limited in Africa. Only a few countries like Morocco, Botswana, Egypt, and South Africa have made building technology parks a key part of their development plans.

Africa in Science (AiS)

Africa in Science (AiS) is an online platform started in 2021. It focuses on analyzing science in Africa. Its main goal is to track and show how much research is produced by universities and research institutes in African countries.

Science and Technology by Country

- Science and technology in Morocco

- Science and technology in Cabo Verde

- Science and technology in Malawi

- Science and technology in Tanzania

- Science and technology in Uganda

- Science and technology in Zimbabwe

- Science and technology in Botswana

- Science and technology in South Africa

See also

- History of Space in Africa

- Maritime history of Somalia

- Timeline of Islamic science and technology

- Science in medieval Islam

- Science in Asia

- Science in Europe

|

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |