Hanseatic League facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hanseatic League

Hanse

Hansa |

|

|---|---|

|

Hanseatic pennant

|

|

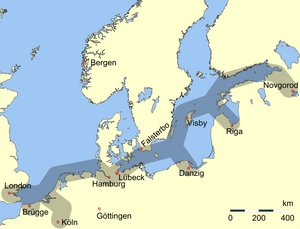

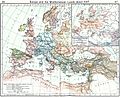

Northern Europe in the 1400s, showing the extent of the Hanseatic League

|

|

| Informal capital | Lübeck (Free City of) |

| Lingua franca | Middle Low German |

| Membership | Various cities across the region of the Baltic and North Seas |

| Today part of | |

Imagine a powerful group of cities that worked together like a team. This was the Hanseatic League, a huge network of merchant groups and towns in Central and Northern Europe. It was active during the Middle Ages, from the 12th to the 17th century.

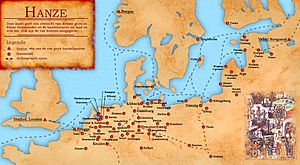

The League started with a few towns in northern Germany. It grew to include almost 200 settlements. These towns were spread across eight countries we know today. They reached from Estonia in the east to the Netherlands in the west. Some even went inland to places like Cologne and Kraków.

The League began as small groups of German traders. They wanted to expand their businesses. They also needed protection from robbers. Over time, these groups joined forces. The League gave traders special rights and kept trade routes safe. Families of merchants often married each other. This helped the cities work even closer. They also made trade rules the same for everyone.

The Hanseatic League was very strong. It controlled most of the sea trade in the North Sea and Baltic Sea. It set up trading posts in many cities. These posts were called Kontors. Important ones were in London, Bruges, Bergen, and Novgorod. These Kontors were like mini-cities with their own rules.

Hanseatic merchants were known as Hansards. They ran their own companies. They had access to many goods and enjoyed special treatment abroad. The League's economic power was so great. It could even stop trade with certain areas. Sometimes, it even went to war against kingdoms.

Even at its strongest, the Hanseatic League was not a single country. It was a loose group of city-states. It did not have a permanent government or a regular army. In the 14th century, the League held meetings called diets. Decisions were made by talking things through and agreeing together. By the mid-16th century, these loose ties made the League weak. Cities started to join other kingdoms or leave the League. It slowly fell apart and ended in 1669.

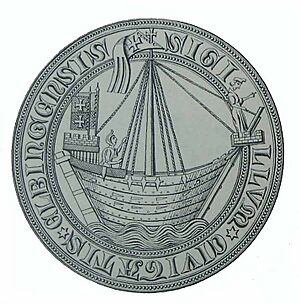

The League used many types of ships. The most famous was the cog. This ship was shown on Hanseatic seals and flags. Later, the cog was replaced by larger ships like the hulk. Then came even bigger carvel ships.

Contents

What Does "Hanse" Mean?

The word Hanse comes from an old German word. It meant a group or troop of people. This word was used for groups of merchants. They traveled between the Hanseatic cities. In a language called Middle Low German, Hanse came to mean a group of merchants or a trade guild. Some people thought it meant "on the sea," but that is not correct.

How the Hanseatic League Started

Before the League, traders, raiders, and pirates were active in the Baltic Sea. Sailors from Gotland sailed far up rivers to Novgorod. This was a big trade center in Russia. People from Scandinavia led the Baltic trade before the League. They set up major trading spots around the 9th century. Many later Hanseatic ports were once part of this Scandinavian trade system.

The Hanseatic League was never formally started on a specific date. Historians often link its beginnings to the rebuilding of Lübeck in 1159. This was done by Henry the Lion, a powerful duke. However, some experts now see Lübeck as one of many trade centers. They think the League grew from two main trade systems. One was in northern Germany, focused on the Baltic. The other was in the Rhineland, trading with England and Flanders.

German cities quickly became very important in Baltic trade during the 13th century. Lübeck became a key city for sea trade. It connected the areas around the North and Baltic seas. Lübeck was most powerful in the 15th century.

Early Development of the League

Even before the word Hanse was used, cities started forming groups. These groups were called guilds or hansas. Their goal was to trade with towns overseas. Especially in the less developed eastern Baltic. This area offered goods like wood, wax, amber, and furs. They also had rye and wheat from inland farms.

Merchant guilds formed in home cities and in places where they traded. They were like early companies. Despite some competition, they worked together more and more. This led to the Hanseatic network of merchant guilds. The main language for trade was Middle Low German. This language greatly influenced other languages in the area. These included Scandinavian languages, Estonian, and Latvian.

Visby, on the island of Gotland, was a main trade center before the Hansa. Visby merchants set up a trading post in Novgorod in 1080. It was called Gutagard. In 1120, Gotland became independent from Sweden. It welcomed traders from other regions. German merchants then often stopped at Gotland. In the early 13th century, they set up their own Kontor in Novgorod. It was called the Peterhof.

Lübeck soon became a base for merchants from Saxony and Westphalia. They traded eastward and northward. Lübeck was more appealing than Schleswig. This was because it had shorter routes and better legal protection. It became a transfer port for trade between the North Sea and the Baltic. Lübeck also gave special trade rights to Russian and Scandinavian traders. It was a main supply port for the Northern Crusades. This helped its standing with the Popes.

Lübeck became a free imperial city in 1226. This meant it was independent within the Holy Roman Empire. Hamburg also became a free city in 1189. Other cities like Wismar, Rostock, Stralsund, and Danzig also got city charters.

Hansa groups worked to remove trade limits for their members. The first mention of a German trade group was in London. This was between 1173 and 1175. Merchants from Cologne convinced King Henry II of England. He agreed to remove all tolls for them in London. He also promised to protect their merchants and goods across England.

German settlers in the 12th and 13th centuries founded many cities. These were on or near the east Baltic coast. Examples include Elbing (Elbląg), Thorn (Toruń), Reval (Tallinn), Riga, and Dorpat (Tartu). All of these cities joined the League. Many still have Hanseatic buildings and styles. Most adopted Lübeck law. This meant they could appeal legal issues to Lübeck's city council. Others used Magdeburg law. Later, the Livonian Confederation (1435–1582) included modern-day Estonia and parts of Latvia. All its major towns were League members.

Over the 13th century, wealthy long-distance traders settled in their hometowns. They became trade leaders. This gave them more power over town policies. Merchants gained higher status. They expanded their influence to more cities. Travel was slow back then. A trip from Reval to Lübeck could take weeks or even months in winter. This helped the cities work together in a decentralized way.

In 1241, Lübeck formed an alliance with Hamburg. This was an early step towards the League. Lübeck had access to fishing grounds. Hamburg controlled salt-trade routes. These cities gained control over most of the salted fish trade. Cologne joined them in 1260. The towns raised their own armies. Each guild had to provide soldiers when needed. Hanseatic cities helped each other. Merchant ships often carried soldiers and weapons. The network of alliances grew. It included 70 to 170 cities.

In the west, cities like Cologne had special trading rights. These were in Flanders and England. In 1266, King Henry III of England gave Lübeck and Hamburg a charter for trade in England. This caused some competition at first. But the Cologne Hansa and the Wendish Hansa joined in 1282. They formed the Hanseatic colony in London. They fully merged in the 15th century.

Novgorod was blocked from trade in 1268 and 1277-1278. Still, Westphalian traders controlled trade in London. They also traded in Ipswich and Colchester. Baltic and Wendish traders focused on King's Lynn and Newcastle upon Tyne. The need for cooperation came from weak local governments. They could not keep trade safe. Over the next 50 years, the merchant Hansa grew stronger. They made formal agreements for cooperation. These covered western and eastern trade routes. Cities from the Low Countries, Utrecht, Holland, and others joined in the 13th century. This network of trading guilds was called the Kaufmannshanse.

How Trade Expanded

The League set up more Kontors. These were in Bruges (Flanders), Bryggen in Bergen (Norway), and London (England). They were in addition to the Peterhof in Novgorod. These trading posts became official by the early 14th century. Except for Bruges, they became important areas with special rights. The London Kontor, called the Steelyard, was a walled community. It had warehouses, offices, and homes.

Besides the main Kontors, smaller ports had Hanseatic trading outposts. These often had a merchant and a warehouse. They were not always staffed. In Scania, Denmark, about 30 Hanseatic seasonal factories made salted herring. These were called vitten. They had their own legal rights. Some historians say they were like a fifth Kontor.

In England, outposts were in Boston, Bristol, King's Lynn, Hull, Ipswich, Newcastle upon Tyne, Norwich, Scarborough, Yarmouth, and York. Many were important for Baltic trade. They became centers for making textiles in the late 14th century. Hanseatic traders and textile makers worked together. They made fabrics that fit local demand and fashion. Outposts in Lisbon, Bordeaux, and Nantes offered cheaper salt. Ships carrying this salt were called the salt fleet. Trading posts also operated in Flanders, Denmark-Norway, Iceland, and Venice.

Hanseatic trade was not only by sea. Many Hanseatic towns were not directly on the coast. They were connected by river trade or even land trade. These formed a connected network. Many smaller Hanseatic towns focused on local trade. Trade within the Hansa was the biggest part of its business. River and land trade did not have special Hanseatic rights. But seaports like Bremen, Hamburg, and Riga controlled trade on their rivers. This was not possible for the Rhine river. Digging canals for trade was rare. However, the Stecknitz Canal was built between Lübeck and Lauenburg from 1391 to 1398.

What Did They Trade?

| Imports | Origin, Destination | Exports | Total | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 150 | London/Hamburg | 38 | 188 | 34.4 | ||

| 44 | Livonian towns: | 51 | 95 | 17.4 | ||

| 10 | Riga | 14 | ||||

| 34 | Reval (Tallinn) | 14.3 | ||||

| - | Pernau | 22.7 | ||||

| 49.4 | Scania | 32.6 | 82 | 15 | ||

| 52 | Gotland, Sweden | 29.4 | 81.4 | 14.9 | ||

| 19 | Prussian towns: | 29.5 | 48.5 | 8.9 | ||

| 16 | Danzig | 22.8 | ||||

| 3 | Elbing | 6.6 | ||||

| 17.2 | Wendish & Pomeranian towns: |

25.2 | 42.4 | 7.8 | ||

| 5.5 | Stettin | 7 | ||||

| 4 | Stralsund | 7.5 | ||||

| 2.2 | Rostock | 4.6 | ||||

| 5.5 | Wismar | 6.1 | ||||

| 4.3 | Bergen | – | 4.3 | 0.8 | ||

| 3 | Small Baltic ports | 1.2 | 4.2 | 0.8 | ||

| 338.9 | Total | 206.9 | 545.8 | 100 |

The Hanseatic League helped grow trade and industry in northern Germany. They started by trading rough wool fabrics. As trade grew, they made finer wool and linen fabrics. They even made silks. Other crafts also improved. These included etching, wood carving, and armor making.

The League mainly traded goods from the east. These included beeswax, furs, wood, tar, flax, honey, wheat, and rye. They sent these to Flanders and England. In return, they got cloth, especially broadcloth, and other manufactured goods. Metal ore (copper and iron) and herring came from Sweden. The Carpathians were another source of copper and iron. Lübeck was key in the salt trade. Salt came from Lüneburg or from France and Portugal. It was sold in Central Europe. It was also used to salt herring in Scania or sent to Russia.

Stockfish (dried fish) was traded from Bergen for grain. Grain from the Hansa helped more people settle in northern Norway. The League also traded beer. Beer from Hanseatic towns was highly valued. Cities like Lübeck, Hamburg, Wismar, and Rostock made beer for export.

How the League Protected Its Power

The Hanseatic League used its power to stay safe. They also used it to gain and keep special rights. Bandits and pirates were always a problem. During wars, privateers (legal pirates) joined in. Traders could be arrested abroad. Their goods could be taken. The League tried to make rules for protection. They made internal agreements for mutual defense. They also made external agreements for special rights.

Many local merchants and nobles were jealous of the League's power. They tried to reduce it. For example, in London, local merchants kept pushing to remove the League's special rights. Most foreign cities limited Hanseatic traders to certain areas. The Hansa did not offer the same special deals to other traders. This made tensions worse.

League merchants used their economic power to pressure cities and rulers. They stopped trade with certain towns. They boycotted entire countries. They blocked trade with Novgorod in 1268 and 1277-1278. Bruges was pressured by moving the Hanseatic trading center to Aardenburg. This happened several times. Boycotts against Norway in 1284 and Flanders in 1358 almost caused famines.

Sometimes, they used military action. Several Hanseatic cities had warships. When needed, they used merchant ships for war. Military action often involved a group of cities working together. This was called an alliance.

To protect their investments, League members trained pilots. They also built lighthouses. One example is Kõpu Lighthouse. Lübeck built what might be northern Europe's first proper lighthouse in Falsterbo in 1202. By 1600, at least 15 lighthouses were built. These were along the German and Scandinavian coasts. This made it the best-lit coast in the world. This was largely thanks to the Hansa.

The League's Strongest Period

The power of the Holy Roman Empire became weaker. This forced the League to create a network of cities. This network was called the Städtehanse. But it never became a formal organization. The Kaufmannshanse (merchant Hansa) still existed. This growth was slowed by Danish kings. They conquered Wendish cities between 1306 and 1319. They also limited their freedom.

Hanseatic towns met regularly in Lübeck. These meetings were called Hansetag (Hanseatic Diet). They started around 1300 or possibly 1356. Many towns did not attend or send representatives. Decisions were not binding if their delegates were not included. Representatives sometimes left early. This gave their towns an excuse not to agree to decisions. Only a few Hanseatic cities were free imperial cities. But many temporarily escaped control by local nobles.

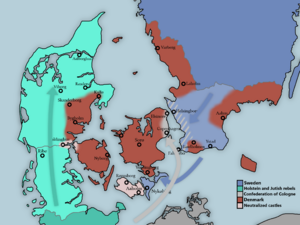

Between 1361 and 1370, League members fought against Denmark. This was the Danish-Hanseatic War. At first, they were not successful. But cities from Prussia and the Netherlands joined forces. They formed the Confederation of Cologne in 1368. They attacked Copenhagen and Helsingborg. They forced the Danish and Norwegian kings to give them tax breaks. They also gained influence over Øresund fortresses for 15 years. This was in the peace treaty of Stralsund in 1370. This treaty gave the League more rights in Scania. The treaty marked the peak of Hanseatic power. During this time, the League was called a "Northern European great power". The Confederation lasted until 1385. The Øresund fortresses were returned to Denmark that year.

After the Danish king's heir died, a fight for the throne began. It was between Albert of Mecklenburg and Margaret I of Denmark. Swedish nobles rebelled against Albert. They invited Margaret to rule. Albert was captured in 1389. But he hired privateers in 1392. These were called the Victual Brothers. They took Bornholm and Visby for him. They threatened sea trade until the 1430s. Albert was released in 1395. As part of the deal, Stockholm was ruled by 7 Hanseatic cities from 1395 to 1398. It then went to Margaret.

The Victual Brothers controlled Gotland in 1398. The Teutonic Order conquered it with help from Prussian towns. The grandmaster of the Teutonic Order was often seen as the head of the Hansa.

When Rival Powers Grew Stronger

Over the 15th century, the League became more organized. This was partly due to challenges in leadership. It also faced competition from rivals. Trade also changed. Cities moved from loose participation to formal recognition. Another trend was that Hanseatic cities made more rules for their Kontors abroad. Only the Bergen Kontor became more independent.

In Novgorod, the League got its trade rights back in 1392. This was after a long conflict since the 1380s. They agreed to Russian trade rights for Livonia and Gotland.

In 1424, all German traders in the Petershof Kontor in Novgorod were jailed. 36 of them died. Arrests and seizures in Novgorod were very violent. In response, the League blocked Novgorod. They left the Peterhof from 1443 to 1448. This was also because of the war between Novgorod and the Livonian Order.

English traders gained trade rights in the Prussian region. This was through treaties in Marienburg (1388, 1409). This happened after conflicts with the League from the 1370s. Their influence grew. The importance of Hanseatic trade in England decreased over the 15th century.

Over the 15th century, tensions grew. This was between the Prussian region and the "Wendish" cities. Lübeck depended on its role as the center of the Hansa. Prussia wanted to export goods like grain and wood. They sent these to England, the Low Countries, Spain, and Italy.

Frederick II, Elector of Brandenburg, tried to control the Hanseatic towns of Berlin and Cölln in 1442. He stopped all Brandenburg towns from joining Hanseatic meetings. For some Brandenburg towns, this ended their League involvement. In 1488, John Cicero, Elector of Brandenburg did the same to Stendal and Salzwedel.

Until 1394, Holland and Zeeland were active in the Hansa. But in 1395, their duties to Albert I, Duke of Bavaria stopped further cooperation. Their Hanseatic ties weakened. Their economic focus changed. Between 1417 and 1432, Holland and Zeeland became part of the Burgundian State.

Lübeck had money problems in 1403. This led to unhappy craftsmen forming a committee in 1405. This caused a government crisis in 1408. The committee rebelled and set up a new town council. Similar revolts happened in Wismar and Rostock. New town councils were set up in 1410. The crisis ended in 1418 with a compromise.

Eric of Pomerania became king in 1412. He tried to expand into Schleswig and Holstein. He charged tolls at the Øresund. Hanseatic cities were divided at first. Lübeck tried to calm Eric. Hamburg supported the counts against him. This led to the Danish-Hanseatic War (1426-1435). It also led to the Bombardment of Copenhagen (1428). The Treaty of Vordingborg renewed the League's trade rights in 1435. But the Øresund tolls continued.

Eric of Pomerania was later removed from power. In 1438, Lübeck took control of the Øresund toll. This caused problems with Holland and Zeeland. The Sound tolls and Lübeck's attempt to exclude English and Dutch merchants from Scania hurt the herring trade there. The excluded regions started their own herring industries.

In the Dutch–Hanseatic War (1438–1441), merchants from Amsterdam fought for free access to the Baltic. They eventually won. The blockade of grain trade hurt Holland and Zeeland more than Hanseatic cities. But it was against Prussia's interest to keep it.

In 1454, the towns of the Prussian Confederation rebelled against the Teutonic Order. They asked Casimir IV Jagiellon of Poland-Lithuania for help. Gdańsk (Danzig), Thorn, and Elbing became part of the Kingdom of Poland. This happened after the Second Peace of Thorn (1466).

Poland was strongly supported by the Holy Roman Empire. This was through family ties and military help. Kraków, the Polish capital, had a loose link with the Hansa. After 1466, there were no customs borders on the River Vistula. This helped Polish grain exports grow. They went from 10,000 tons per year in the late 15th century to over 200,000 tons in the 17th century. The Hansa controlled the sea grain trade. This made Poland a key area for its business. It also helped Danzig become the Hansa's largest city. Polish kings soon began to reduce the towns' political freedoms.

Starting in the mid-15th century, the dukes of Pomerania fought constantly. They wanted control of the Pomeranian Hanseatic towns. Bogislav X eventually took control of Stettin and Köslin. This hurt the region's economy and independence.

A big advantage for the Hansa was its control of shipbuilding. This was mainly in Lübeck and Danzig. The League sold ships all over Europe.

The economic problems of the late 15th century also affected the Hansa. But its main rivals were growing territorial states. New ways of using credit came from Italy.

When Flanders and Holland became part of the Duchy of Burgundy, they started to exclude Lübeck. This was from their grain trade in the 15th and 16th centuries. Demand for Prussian and Livonian grain grew in the late 15th century. These trade interests were different from Wendish interests. This threatened the League's unity. Hollandish shipping costs were much lower than the Hansa's. The Hansa was cut out as a middleman. After naval wars, Amsterdam became the main port for Polish and Baltic grain. This happened from the late 15th century onwards.

Nuremberg in Franconia developed a land route. They sold products that the Hansa used to control. These went from Frankfurt through Nuremberg and Leipzig to Poland and Russia. They traded Flemish cloth and French wine for grain and furs from the east. The Hansa benefited from this trade. They allowed Nurembergers to settle in Hanseatic towns. These traders took over trade with Sweden as well. The Nuremberger merchant Albrecht Moldenhauer helped develop trade with Sweden and Norway. His sons became leaders of Hanseatic activities in Bergen and Stockholm.

King Edward IV of England confirmed the League's special rights. This was in the Treaty of Utrecht. This happened despite hidden problems. It was partly because the League gave a lot of money to the Yorkist side. This was during the Wars of the Roses (1455–1487).

Tsar Ivan III of Russia closed the Hanseatic Kontor at Novgorod in 1494. He sent its merchants to Moscow. He wanted to reduce Hanseatic influence on Russian trade. At that time, only 49 traders were at the Peterhof. The fur trade moved to Leipzig. This cut out the Hansards. Hanseatic trade with Russia moved to Riga, Reval, and Pleskau. When the Peterhof reopened in 1514, Novgorod was no longer a major trade hub. At the same time, people in Bergen tried to trade directly with northern populations. They did this against the Hansards' wishes. The League's existence and its special rights caused problems. These often led to rivalries between League members.

The End of the Hansa

Trade across the Atlantic Ocean grew after the Americas were discovered. This caused the remaining Kontors to decline. Especially in Bruges, as it focused on other ports. It also changed how business was done. Short-term contracts became common. This made the Hanseatic model of guaranteed trade old-fashioned.

Local rulers continued to take control of towns. They also stopped Hanseatic traders from having special rights. These trends continued into the next century.

In the Swedish War of Liberation (1521–1523), the Hanseatic League won. This was against an economic conflict. It was about trade, mining, and metal in Sweden. Jakob Fugger, a powerful industrialist, tried to take over the business. He allied with the Pope, the Holy Roman Emperor, and the King of Denmark/Norway. Both sides spent a lot of money on soldiers to win the war. After the war, Sweden and Denmark followed their own policies. They did not support Lübeck against Dutch trade.

However, Lübeck, under Jürgen Wullenwever, tried to do too much. This was in the Count's Feud in Scania and Denmark. Lübeck lost influence in 1536 after Christian III won. Lübeck tried to force competitors out of the Sound. This eventually made even Gustav Vasa angry. Its influence in the Nordic countries began to decline.

The Hanseatic towns in Guelders faced problems in the 1530s. This was from Charles II, Duke of Guelders. Charles was a strict Catholic. He did not like the Lutheranism of Lübeck and other German cities. This made trade difficult but did not end it. A small comeback happened later.

Later in the 16th century, Denmark-Norway took control of much of the Baltic. Sweden had regained control over its own trade. The Kontor in Novgorod had closed. The Kontor in Bruges was almost dead. This was because the Zwin inlet was silting up. Finally, German princes gained more political power. This limited the independence of Hanseatic towns.

The League tried to fix some of these issues. It created the job of syndic in 1556. Heinrich Sudermann was elected to this role. He worked to protect and expand the agreements of the member towns. In 1557 and 1579, new agreements were made. They explained the duties of towns. Some progress was made. The Bruges Kontor moved to Antwerp in 1520. The Hansa tried to find new trade routes. However, the League could not stop the growing competition.

In 1567, a Hanseatic League agreement confirmed old duties and rights. These included common protection and defense. Cities from Prussia, Livonia, and Dorpat also signed. When pressured by the King of Poland-Lithuania, Danzig stayed neutral. It did not allow ships going to Poland into its area. They had to anchor elsewhere.

The Antwerp Kontor closed in 1593. It was already weak after the fall of the city. In 1597, Queen Elizabeth I expelled the League from London. The Steelyard closed in 1598. The Kontor returned in 1606 under James I. But it never recovered. The Bergen Kontor continued until 1754. Of all the Kontors, only its buildings, the Bryggen, still stand.

Not all states tried to stop their cities' Hanseatic links. The Dutch Republic encouraged its eastern former members to keep ties. The States-General used these cities in diplomacy during the Kalmar War.

The Thirty Years' War was very damaging for the Hanseatic League. Members suffered greatly from imperial, Danish, and Swedish forces. At first, Saxon and Wendish cities were attacked. This was because Christian IV of Denmark wanted to control the Elbe and Weser rivers. Pomerania lost many people. Sweden took control of Bremen-Verden, Swedish Pomerania, and Swedish Wismar. This stopped their cities from joining the League. Sweden controlled the Oder, Weser, and Elbe rivers. It could charge tolls on traffic. The League became less and less important. This was despite its inclusion in the Peace of Westphalia.

In 1666, the Steelyard burned down in the Great Fire of London. The Kontor manager asked Lübeck for money to rebuild. Hamburg, Bremen, and Lübeck called for a Hanseatic Day in 1669. Only a few cities came. Those who did were unwilling to pay for the rebuilding. This was the last official meeting. No one knew it at the time. This date is often seen as the end of the Hansa. But the League never formally broke up. It just slowly disappeared.

What Happened After the Hansa?

The Hanseatic League, however, stayed in people's minds. Leopold I even asked Lübeck to call a meeting. He wanted support against the Turks.

Lübeck, Hamburg, and Bremen kept trying to work together. But their interests had changed by the Peace of Ryswick. Still, the Hanseatic Republics managed some joint diplomacy. For example, they sent a joint group to the United States in 1827. Later, the United States had a consul for the Hanseatic and Free Cities. Britain also had diplomats to the Hanseatic Cities until Germany united in 1871. The three cities also had a common "Hanseatic" office in Berlin until 1920.

Three Kontors remained as Hanseatic property after the League ended. The Peterhof had closed in the 16th century. Bryggen was sold to Norwegian owners in 1754. The Steelyard in London and the Oostershuis in Antwerp were hard to sell. The Steelyard was finally sold in 1852. The Oostershuis, which closed in 1593, was sold in 1862.

Hamburg, Bremen, and Lübeck were the only members until the League's formal end in 1862. This was just before Germany united in 1871. Despite its end, they valued their link to the Hanseatic League. Until Germany reunited, these three cities were the only ones that kept "Hanseatic City" in their official German names. Hamburg and Bremen still call themselves "free Hanseatic cities". Lübeck is named "Hanseatic City". For Lübeck, this old tie to a great past was important in the 20th century. In 1937, the Nazi Party removed its special status. Since 1990, 24 other German cities have adopted this title.

How the League Was Organized

The Hanseatic League was a complex group. It was a loose collection of cities. They worked together for shared goals. These goals included controlling trade in the Baltic region. They also wanted to be as independent as possible from local rulers. It was not a single, unified organization or a "state within a state." It grew from merchant guilds into a more formal group of cities. But it never became a single legal entity.

Most League members spoke Middle Low German. Dinant was an exception. Not all towns with Low German merchants were members. For example, Emden and Narva were not. To be a member, you usually had to be born to German parents. You also had to follow German law and have a business education. The League worked to help its members. It helped them with trade and kept them independent.

Decisions in the League were made by agreement. When a problem came up, members were invited to a central meeting. This was called the Tagfahrt (Hanseatic Diet). It may have started around 1300. It became more formal after 1358. Member cities chose representatives to attend. These representatives shared their city's views. Not every city sent someone. Delegates often represented several cities. Decisions were made by consensus. This meant that if no one objected, the proposal passed. If there was no agreement, members were chosen to find a compromise.

The League had many different laws. The meetings could not make new laws. But the cities worked together on trade rules. For example, they fought against fraud. They also worked together on a regional level. They tried to make sea laws the same. They created several rules in the 15th and 16th centuries. The most detailed was the Ship Ordinance and Sea Law of 1614. But it might not have been fully enforced.

What Were Kontors?

A Hanseatic Kontor was a settlement of Hansard merchants. They were organized like a private company. They had their own money, court, laws, and seal. They worked like an early stock exchange. Kontors were first set up for safety. But they also helped secure special rights and deal with other countries. They checked the quality of goods. This made trade more efficient. They also helped build connections with local rulers. They were sources of economic and political information.

Most Kontors were physical places with buildings. These buildings were sometimes separate from city life. The kontor of Bruges was different. It only got its own buildings in the 15th century. Like the guilds, the Kontors were usually led by Ältermänner (eldermen). The Stalhof in London had both a Hanseatic and an English alderman. In Novgorod, the aldermen were replaced by a hofknecht in the 15th century. The rules of the Kontors were read aloud to merchants once a year.

In 1347, the Kontor of Bruges changed its rules. It wanted to make sure all League members were equally represented. Members from different regions were grouped into three circles. These were called Drittel (thirds). They were the Wendish and Saxon Drittel, the Westphalian and Prussian Drittel, and the Gothlandian, Livonian, and Swedish Drittel. Merchants from each Drittel chose two aldermen. They also chose six members for the Eighteen Men Council. This council managed the Kontor for a set time.

In 1356, the League confirmed this rule. This was during a meeting before the first Tagfahrt. All trading settlements, including the Kontors, had to follow the Diet's decisions. Their representatives could attend and speak at meetings. But they could not vote.

League Divisions: Drittel and Quartiere

The League slowly divided itself into three parts. These were called Drittel (thirds).

| Drittel (1356–1554) | Regions | Chief city (Vorort) |

|---|---|---|

| Wendish-Saxon | Holstein, Saxony, Mecklenburg, Pomerania, Brandenburg | Lübeck |

| Westphalian-Prussian | Westphalia, Rhineland, Prussia | Dortmund, later Cologne |

| Gothlandian-Livonian-Swedish | Gotland, Livonia, Sweden | Visby, later Riga |

The Hansetag was the only central group of the Hanseatic League. But with the Drittel system, members often held their own meetings. These were called Dritteltage (Drittel meetings). They worked out common ideas to present at the Hansetag. On a more local level, League members also met. These regional meetings became more important. They helped prepare and carry out the Diet's decisions.

From 1554, the Drittel system changed. It became four Quartiere (quarters). This was to make the groups more similar. It also helped members work better together regionally. This made the League's decisions more efficient.

| Quartier (since 1554) | Chief city (Vorort) |

|---|---|

| Wendish and Pomeranian | Lübeck |

| Saxon, Thuringian and Brandenburg | Brunswick, Magdeburg |

| Prussia, Livonia and Sweden – or East Baltic | Danzig (now Gdańsk) |

| Rhine, Westphalia and the Netherlands | Cologne |

However, the Kontors did not use this new division. They grouped League members in different ways for their own purposes.

Hanseatic Ships

The League used different kinds of ships.

The Cog

The most common and famous ship was the cog. It was a multi-purpose ship. It had a flat bottom and a rudder at the back. It also had a single mast with a square sail. Most cogs were owned by private people. They were also used as warships. Cogs came in different sizes. They were used on both seas and rivers. They could have castles added from the 13th century. The cog was shown on many seals and flags of Hanseatic cities. These included Stralsund, Elbląg, and Wismar. Several shipwrecks have been found. The most famous is the Bremen cog. It could carry about 125 tons of cargo.

The Hulk

The hulk started to replace the cog by 1400. Cogs lost their main role around 1450. The Hulk was a bigger ship. It could carry more cargo. Some estimate they could carry up to 500 tons by the 15th century. No archaeological evidence of a hulk has been found.

The Carvel

In 1464, Danzig got a French carvel ship. It was renamed the Peter von Danzig. It was 40 meters long and had three masts. It was one of the largest ships of its time. Danzig started building carvels around 1470. Other cities also switched to carvels around this time. An example is the Jesus of Lübeck. It was later sold to England. It was used as a warship and a slave ship.

The galleon-like carvel warship Adler von Lübeck was built by Lübeck. It was for military use against Sweden. This was during the Northern Seven Years' War (1563–70). It was launched in 1566. But it was never used in war after the Treaty of Stettin. It was the biggest ship of its day. It was 78 meters long and had four masts. It served as a merchant ship until 1581. It was damaged on a trip from Lisbon and taken apart in 1588.

Hanseatic Cities and Trading Posts

Main Hanseatic Cities

In the table below, the "Quarter" column shows the main regions of the League.

- "Wendish": Wendish and Pomeranian quarter

- "Saxon": Saxon, Thuringian and Brandenburg quarter

- "Baltic": Prussian, Livonian and Swedish (or East Baltic) quarter

- "Westphalian": Rhine, Westphalia and the Netherlands (including Flanders) quarter

| Quarter | City | Territory | Now | From | Until | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wendish | Lübeck | Free City of Lübeck | Capital of the Hanseatic League, the main town of the Wendish and Pomeranian Circle |

|

|||

| Wendish | Hamburg | Free City of Hamburg |

|

||||

| Wendish | Lüneburg | Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg |

|

||||

| Wendish | Wismar | Duchy of Mecklenburg | Joined the 10-year Rostock Peace Treaty (Rostocker Landfrieden) in 1283, which was the predecessor of the federation of Wendish towns (1293 onwards). |

|

|||

| Wendish | Rostock | Duchy of Mecklenburg | Joined the 10-year Rostock Peace Treaty in 1283, which was the predecessor of the federation of Wendish towns (1293 onwards). |

|

|||

| Wendish | Stralsund | Principality of Rügen | 1,293 | Rügen was a fief of the Danish crown to 1325. Stralsund joined the 10-year Rostock Peace Treaty in 1283, which was the predecessor of the federation of Wendish towns (1293 onwards). From 1339 to the 17th century, Stralsund was a member of the Vierstädtebund with Greifswald, Demmin and Anklam. |

|

||

| Wendish | Demmin | Duchy of Pomerania | Joined the 10-year Rostock Peace Treaty in 1283, which was the predecessor of the federation of Wendish towns (1293 onwards). From 1339 to the 17th century, Demmin was a member of the Vierstädtebund with Stralsund, Greifswald and Anklam. |

|

|||

| Wendish | Greifswald | Duchy of Pomerania | Joined the 10-year Rostock Peace Treaty in 1283, which was the predecessor of the federation of Wendish towns (1293 onwards). From 1339 to the 17th century, Greifswald was a member of the Vierstädtebund with Stralsund, Demmin and Anklam. |

|

|||

| Wendish | Anklam | Duchy of Pomerania | Joined the 10-year Rostock Peace Treaty in 1283, which was the predecessor of the federation of Wendish towns (1293 onwards). From 1339 to the 17th century, Anklam was a member of the Vierstädtebund with Stralsund, Greifswald and Demmin. |

|

|||

| Wendish | Stettin (Szczecin) | Duchy of Pomerania | 1,278 | Joined the 10-year Rostock Peace Treaty in 1283, which was the predecessor of the federation of Wendish towns (1293 onwards); since the 14th century gradually adopted the role of a chief city for the Pomeranian Hanse towns to its east |

|

||

| Wendish | Pasewalk | Duchy of Pomerania | |||||

| Wendish | Kolberg (Kołobrzeg) | Duchy of Pomerania |

|

||||

| Wendish | Image:POL Darłowo COA 1.svg Rügenwalde (Darłowo) | Duchy of Pomerania |

|

||||

| Wendish | Stolp (Słupsk) | Duchy of Pomerania |

|

||||

| Wendish | Stargard | Duchy of Pomerania |

|

||||

| Baltic | Visby | Kingdom of Sweden | 1,470 | In 1285 at Kalmar, the League agreed with Magnus III, King of Sweden, that Gotland be joined with Sweden. In 1470, Visby's status was rescinded by the League, with Lübeck razing the city's churches in May 1525. |

|

||

| Saxon | Braunschweig | Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg | 13th cent. | 17th cent. | Main town of the Saxon, Thuringian and Brandenburg Circle |

|

|

| Saxon | Bremen | Free City of Bremen | 1,260 |

|

|||

| Saxon | Magdeburg | Archbishopric of Magdeburg | 13th cent. | Main town of the Saxon, Thuringian and Brandenburg Circle |

|

||

| Saxon | Goslar | Imperial City of Goslar | 1,267 | 1,566 | Goslar was a fief of Saxony until 1280. |

|

|

| Saxon | Hanover | Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg |

|

||||

| Saxon | Göttingen | Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg |

|

||||

| Saxon | Erfurt | Archbishopric of Mainz | 1,430 |

|

|||

| Saxon | Stade | Archbishopric of Bremen |

|

||||

| Saxon | Berlin | Margraviate of Brandenburg | 1,442 | Brandenburg was raised to an Electorate in 1356. Elector Frederick II caused all the Brandenburg cities to leave the League in 1442. |

|

||

| Saxon |

Frankfurt an der Oder |

Margraviate of Brandenburg | 1,430 | 1,442 | Elector Frederick II caused all the Brandenburg cities to leave the League in 1442. |

|

|

| Saxon | Salzwedel | Margraviate of Brandenburg | 1,263 | 1,518 | In 1488 the Hanseatic cities of the Altmark region rebelled against a beer tax against Elector of Brandenburg John Cicero. They lost and were punished by being forced to leave the Hanseatic League. Salzwedel and Stendal managed to stay in the Hanseatic League until 1518. |

|

|

| Saxon | Uelzen | Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg | |||||

| Saxon | Stendal | Margraviate of Brandenburg | 1,358 | 1,518 | In 1488 the Hanseatic cities of the Altmark region rebelled against a beer tax against Elector of Brandenburg John Cicero. They lost and were punished by being forced to leave the Hanseatic League. Salzwedel and Stendal managed to stay in the Hanseatic League until 1518. |

|

|

| Saxon | Hamelin |

|

|||||

| Baltic | Danzig (Gdańsk) | Teutonic Order | 1,358 | Main town of the Prussian, Livonian and Swedish (or East Baltic) Circle. Danzig had been first a part of the Duchy of Pomerelia with a Kashubian and a growing German population, then part of the State of the Teutonic Order from 1308 until 1457. After the Second Peace of Thorn (1466) Danzig became an autonomous city under the protection of the Polish Crown until the 18th century when it was annexed by Prussia. |

|

||

| Baltic | Elbing (Elbląg) | Teutonic Order | 1,358 | Elbing had originally been part of the territory of the Old Prussians, until the 1230s when it became part of the State of the Teutonic Order. After the Second Peace of Thorn (1466), Royal Prussia, including Elbląg was part of the Kingdom of Poland. |

|

||

| Baltic | Thorn (Toruń) | Teutonic Order | 1,280 | Toruń was part of the State of the Teutonic Order from 1233 until 1466. After the Second Peace of Thorn (1466), Royal Prussia, including Toruń, was part of the Kingdom of Poland. |

|

||

| Baltic | Kraków | Kingdom of Poland | 1,370 | 1,500 | Kraków was the capital of the Kingdom of Poland, 1038–1596/1611. It adopted Magdeburg town law and 5000 Poles and 3500 Germans lived within the city proper in the 15th century; Poles steadily rose in the ranks of guild memberships reaching 41% of guild members in 1500. It was very loosely associated with Hansa, and paid no membership fees, nor sent representatives to League meetings. |

|

|

| Baltic | Breslau, (Wrocław) | Kingdom of Bohemia | 1,387 | 1,474 | Breslau, a part of the Duchy of Breslau and the Kingdom of Bohemia, was only loosely connected to the League and paid no membership fees nor did its representatives take part in Hansa meetings |

|

|

| Baltic | Culm (Chełmno) | Teutonic Order | |||||

| Baltic | Königsberg (Kaliningrad) | Teutonic Order | 1,340 | Königsberg was the capital of the Teutonic Order, it accepted the sovereignty of the Polish crown in 1466. It became Ducal Prussia in 1525 after secularisation, a German principality that was a fief of the Polish crown until gaining its independence in the 1660 Treaty of Oliva. The city was renamed Kaliningrad in 1946 after East Prussia was divided between the People's Republic of Poland and the Soviet Union at the Potsdam Conference. |

|

||

| Baltic | Riga | Terra Mariana (Livonia) | 1,282 | During the Livonian War (1558–83), Riga became a Free imperial city until the 1581 Treaty of Drohiczyn ceded Livonia to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth until the city was captured by Sweden in the Polish–Swedish War (1621–1625). |

|

||

| Baltic | Reval (Tallinn) | Terra Mariana (Livonia) | 1,285 | On joining the Hanseatic League, Reval was a Danish fief, but was sold in 1346, with the rest of northern Estonia, to the Teutonic Order. In 1561, Reval became a dominion of Sweden. |

|

||

| Baltic | Dorpat (Tartu) | Terra Mariana (Livonia) | 1280s | The Bishopric of Dorpat had increasing autonomy within the Terra Mariana (Livonian confederation). With the Treaty of Drohiczyn in 1581, Dorpat fell under the rule of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth until the city was captured by Sweden in the Polish–Swedish War (1621–1625). |

|

||

| Baltic | Fellin (Viljandi) | Terra Mariana (Livonia) |

|

||||

| Baltic | Pernau (Pärnu) | Terra Mariana (Livonia) |

|

||||

| Baltic | Wenden (Cēsis) | Terra Mariana (Livonia) |

|

||||

| Baltic | Kokenhusen (Koknese) | Terra Mariana (Livonia) |

|

||||

| Baltic | Roop (Straupe) | Terra Mariana (Livonia) |

|

||||

| Baltic | Windau (Ventspils) | Terra Mariana (Livonia) |

|

||||

| Baltic | Haapsalu (Hapsal) | Terra Mariana (Livonia) |

|

||||

| Baltic | Lemsal (Limbaži) | Terra Mariana (Livonia) |

|

||||

| Baltic | Wolmar (Valmiera) | Terra Mariana (Livonia) |

|

||||

| Baltic | Goldingen (Kuldīga) | Terra Mariana (Livonia) |

|

||||

| Westphalian | Cologne | Imperial City of Cologne | 1,669 | Main town of the Rhine-Westphalian and Netherlands Circle until after the Anglo-Hanseatic War (1470–74), when the city was prosecuted in 1475 with temporary trade sanctions (German: Verhanst) for some years for having supported England; Dortmund was made main town of the Circle. Cologne also was called "Electorate of Cologne" (German: Kurfürstentum Köln or Kurköln). In June 1669 the last Hanseday was held in the town of Lübeck by the last remaining Hanse members, amongst others Cologne. |

|

||

| Westphalian | Dortmund | Imperial City of Dortmund | After Cologne was excluded after the Anglo-Hanseatic War (1470–74), Dortmund was made the main town of the Rhine-Westphalian and Netherlands Circle. |

|

|||

| Westphalian | Dinant |

|

|||||

| Westphalian | Deventer | Bishopric of Utrecht | 1,500 |

|

|||

| Westphalian | Nijmegen | Jülich-Guelders |

|

||||

| Westphalian | Kampen | Bishopric of Utrecht | 1,441 |

|

|||

| Westphalian | Zwolle | Utrecht | 1294 |

|

|||

| Westphalian | Groningen | Friesland |

|

||||

| Westphalian | Roermond | Jülich-Guelders |

|

||||

| Westphalian | Arnhem | Jülich-Guelders |

|

||||

| Bolsward | Frisia |

|

|||||

| Stavoren (Starum) | Frisia | ||||||

| Westphalian | Doesburg | Jülich-Guelders |

|

||||

| Westphalian | Zutphen | Jülich-Guelders |

|

||||

| Westphalian | Harderwijk | Jülich-Guelders | |||||

| Westphalian | Venlo | Jülich-Guelders | |||||

| Westphalian | Hattem | Jülich-Guelders |

|

||||

| Westphalian | Elburg | Jülich-Guelders |

|

||||

| Westphalian | Ommen | Utrecht | |||||

| Westphalian | Tiel | Utrecht | |||||

| Westphalian | Hasselt | Utrecht |

|

||||

| Westphalian | Oldenzaal | Utrecht |

|

||||

| Westphalian | Zaltbommel | Jülich-Guelders | |||||

| Westphalian | Münster | Prince-Bishopric of Münster |

|

||||

| Westphalian | Osnabrück | Prince-Bishopric of Osnabrück | 12th cent. |

|

|||

| Westphalian | Wesel | ||||||

| Westphalian | Soest | Imperial City of Soest | 1,609 | The city was a part of the Electorate of Cologne until acquiring its freedom in 1444–49, after which it aligned with the Duchy of Cleves. |

|

||

| Westphalian | Paderborn |

|

|||||

| Westphalian | Lemgo |

|

|||||

| Minden |

|

Important Foreign Trading Posts (Kontore)

The kontore were the main foreign trading posts of the League. These were not cities that were full Hanseatic members.

| Type | City | Territory | Now | From | Until | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kontor | Novgorod: Peterhof | Novgorod Republic | 1500s | Novgorod was one of the principal Kontore of the League and the easternmost. In 1494, Ivan III, Grand Prince of Moscow, closed the Peterhof; it was reopened a few years later, but the League's Russian trade never recovered. |

|

||

| Kontor | Bergen: Bryggen | Kingdom of Norway | 1,360 | 1,775 | Bryggen was one of the principal Kontore of the League. It was razed by accidental fire in 1476. In 1560, administration of Bryggen was placed under Norwegian administration. |

|

|

| Kontor | Bruges: Hanzekantoor | County of Flanders | Bruges was one of the principal Kontore of the League until the 15th century, when the seaway to the city silted up; trade from Antwerp benefiting from Bruges's loss. |

|

|||

| Kontor | London: Steelyard | Kingdom of England | 1,303 | 1,853 | The Steelyard was one of the principal Kontore of the League. King Edward I granted a Carta Mercatoria in 1303. The Steelyard was destroyed in 1469 and Edward IV exempted Cologne merchants, leading to the Anglo-Hanseatic War (1470–74). The Treaty of Utrecht, sealing the peace, led to the League purchasing the Steelyard outright in 1475, with Edward having renewed the League's privileges without insisting on reciprocal rights for English merchants in the Baltic. London merchants persuaded Elizabeth I to rescind the League's privileges on 13 January 1598; while the Steelyard was re-established by James I, the advantage never returned. Consulates continued however, providing communication during the Napoleonic Wars, and the Hanseatic interest was only sold in 1853. |

|

|

| Kontor | Antwerp | Duchy of Brabant | Antwerp became a major Kontor of the League, particularly after the seaway to Bruges silted up in the 15th century, leading to its fortunes waning in Antwerp's favour, despite Antwerp's refusal to grant special privileges to the League's merchants. Between 1312 and 1406, Antwerp was a margraviate, independent of Brabant. |

|

Vitten: Special Trading Posts

The vitten were important foreign trading posts in Scania. They were not full Hanseatic members. Some historians say they were like the Kontors.

| Type | City | Territory | Now | From | Until | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitte | Malmö | Kingdom of Denmark | 15th cent. | Skåne (Scania) was Danish until ceded to Sweden by the 1658 Treaty of Roskilde, during the Second Northern War. |

|

||

| Vitte | Falsterbo | Kingdom of Denmark | 15th cent. | Skåne was Danish until ceded to Sweden by the 1658 Treaty of Roskilde, during the Second Northern War. |

|

Ports with Hanseatic Trading Posts

- Åhus

- Berwick-upon-Tweed

- Bishop's Lynn (King's Lynn)

- Boston

- Bordeaux

- Bourgneuf

- Bristol

- Copenhagen

- Damme

- Frankfurt

- Ghent

- Hull (Kingston upon Hull)

- Ipswich

- Kalundborg

- Kaunas

- Landskrona

- La Rochelle

- Leith

- Lisbon

- Nantes

- Narva

- Næstved

- Newcastle

- Norwich

- Nuremberg

- Oslo

- Pleskau (Pskov)

- Polotsk

- Rønne

- Scarborough

- Yarmouth (Great Yarmouth)

- Sluis

- Smolensk

- Tønsberg

- Venice

- Vilnius

- Vitebsk

- York

- Ystad

The Hanseatic League's Legacy

How Historians See the League

Historians started studying the Hanseatic League seriously with Georg Sartorius in 1795. He saw the League as a liberal trading group. Later, German historians used the League's history to support a stronger German navy. They linked the League to the rise of Prussia. This view was common from the 1850s until World War I. It greatly influenced how Baltic trade history was seen.

After World War I, historians looked more at social, cultural, and economic history. But some, like Fritz Rörig, also promoted Nazi ideas. After World War II, the nationalist view was dropped. This allowed German, Swedish, and Norwegian historians to share ideas. Views on the League were very negative in Scandinavian countries. Especially in Denmark. This was because it was linked to German power.

Philippe Dollinger's book The German Hansa became a key work in the 1960s. At that time, the main idea was that the League was a loosely connected trading network. Marxist historians debated if the League was "late feudal" or "proto-capitalist."

Two museums in Europe are about the Hanseatic League. They are the European Hansemuseum in Lübeck and the Hanseatic Museum and Schøtstuene in Bergen.

Popular Views of the League

From the 19th century, the Hanseatic League's history was used to promote German national pride. German writers created stories about Jürgen Wullenwever. These stories showed strong anti-Danish feelings. Hanseatic topics were used to promote nation-building and naval power. The League was shown as bringing culture and leading German expansion.

In the 19th century, German painters often painted Hanseatic ships. They wanted the ships to look impressive. So, they ignored history and made cogs look like tall, multi-masted ships. These misleading pictures were widely copied. They influenced how people saw the League throughout the 20th century.

In the late 19th century, a different view appeared. Opponents of the League were shown as heroes. They were seen as freeing people from economic problems. This view was popular until the 1930s. It still exists in the Störtebeker Festival on Rügen.

Since the late 1970s, the League's role in European cooperation became popular. It is now linked with new ideas, business, and international trade. It is often used for tourism and marketing. The League's unique way of governing is seen as an early example of a supranational model. This is like the European Union.

Modern Groups Named After the Hanseatic League

Union of Cities THE HANSA

In 1979, Zwolle invited over 40 cities. These were from West Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Norway. All had historical links to the Hanseatic League. They met in Zwolle in 1980. They formed a "new Hanse" called Städtebund Die Hanse. They also brought back the Hanseatic diets. This new league is open to all former Hanseatic League members. It also includes cities with a Hanseatic past.

In 2012, this city league had 187 members. This included twelve Russian cities, like Novgorod. It also had 21 Polish cities. No Danish cities had joined, even though many could. The "new Hanse" helps with business, tourism, and cultural exchange.

The main office of the New Hansa is in Lübeck, Germany.

Many Dutch cities now call themselves Hanse cities. These include Groningen, Deventer, Kampen, Zutphen, and Zwolle. Many German cities also do this. Their car license plates even start with H. For example, HB is for "Hansestadt Bremen".

Each year, one of the New Hansa member cities hosts a festival. It is called the Hanseatic Days of New Time.

In 2006, King's Lynn became the first English member. Hull joined in 2012. Boston joined in 2016.

New Hanseatic League

The New Hanseatic League was formed in February 2018. Finance ministers from Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, and Sweden started it. They signed a document. It showed their "shared views and values" on the EMU.

Other Legacies

The Hansa's history is seen in several names today.

- The German airline Lufthansa means "Air Hansa."

- F.C. Hansa Rostock is a German football club. It is nicknamed the Kogge or Hansa-Kogge.

- Hansa-Park is a big theme park in Germany.

- Hanze University of Applied Sciences is in Groningen, Netherlands.

- The Hanze oil production platform is in the Netherlands.

- The Hansa Brewery is in Bergen.

- The Hanse Sail is in Rostock.

- The Hanseatic Trade Center is in Hamburg.

- DDG Hansa was a major German shipping company.

- The New Hanza City district is in Riga, Latvia.

- Hansabank in Estonia was renamed Swedbank.

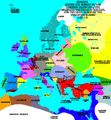

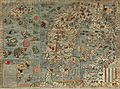

Historical Maps

-

Carta marina of the Baltic Sea region (1539)

See also

In Spanish: Liga Hanseática para niños

In Spanish: Liga Hanseática para niños