Regional cuisines of medieval Europe facts for kids

The regional cuisines of medieval Europe were shaped by many things. These included the weather, what foods were available each season, how countries were governed, and religious traditions. Even though there were many differences, we can see some general patterns in what people ate across Europe.

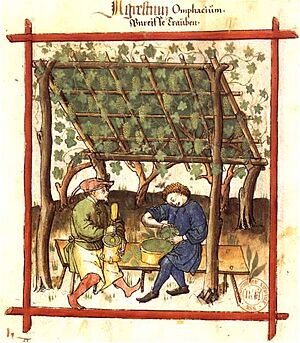

In places like the British Isles, northern France, the Low Countries, northern Germany, Scandinavia, and the Baltic region, the weather was too cold for growing grapes and olives. In the warmer southern areas, wine was a common drink for everyone, rich or poor. However, in the north, beer was the usual drink for common people, and wine was an expensive import. Fruits like citrus (though not the kinds we see today) and pomegranates were common around the Mediterranean Sea. Dried figs and dates were found in the north, but they were not used much in cooking.

Olive oil was a very common ingredient in the Mediterranean region. But in the north, it was costly to import. Oils made from poppy seeds, walnuts, and hazelnuts were cheaper options. After the Black Death plague, people in northern and northwestern Europe, especially in the Low Countries, started using a lot of butter and lard for cooking. Almost everyone in the middle and upper classes across Europe used almonds. They were often made into almond milk, which was very useful. It could be used instead of eggs or regular milk in many dishes.

Contents

Food in Central Europe

German Cooking

During the Middle Ages, there wasn't one big country called Germany. Instead, the area was made up of many small kingdoms and free cities. Later, the Hanseatic League, a powerful group of trading cities, also controlled many ports. Most of these areas were loosely part of the Holy Roman Empire. When we talk about "Germany" here, we mean the lands where German languages were spoken. This stretched from Alsace in the west to Silesia in the east, and from Tyrol in the south to the Baltic Sea in the north.

Many parts of Europe enjoyed dishes made from batter or dough cooked in fat. These included crêpes, fritters, and doughnuts. But they were especially popular in Germany, where they were called krapfen. These were similar to today's deep-fried pastries. Germans were known for using a lot of lard and butter in their cooking. This made people think of them as "fat Germans."

The Catholic Church had rules about fasting, which meant not eating meat on certain days. This was a challenge for Germans. Olives couldn't grow there, and olive oil was expensive to bring in. Oils from nuts were available, but not in large amounts. The main fats used were butter and, most of all, lard. Fish was generally more expensive. For wealthier families, buying fish for fasting days could greatly increase their food costs.

Mustard was used in Germany more than in other parts of Europe. A French poet named Eustache Deschamps wrote in the 14th century that he didn't like how Germans put a lot of mustard on almost every kind of meat.

Cookbooks rarely included recipes for emergencies. But one old cookbook from northern Germany has a recipe for a wartime stew. It tells you to boil any available greens and vegetables in animal stomachs or intestines. This was a clever way to cook when there were no proper pots. During the First Margrave War, the city of Nuremberg managed to feed its people well and win. They did this by planning carefully, storing lots of grain and meat, and controlling food prices.

Polish Cooking

The most common grains in Poland were millet and wheat. Millet was often made into kasza, a type of porridge. Barley and oats were grown, but mostly used to feed animals or make beer. Common vegetables included cabbage (especially as sauerkraut), kale, peas, broad beans, and onions. Dill and mustard were used almost everywhere as herbs. Parsley was used in stews, for flavor, and to add color to fancy dishes for rich people.

The most common meats were beef, pork, and poultry (mostly chicken). Sometimes, people ate mutton and lamb. Game meat, like deer or wild boar, was highly valued but hard to get. Only rich nobles usually had it, as hunting was controlled by landowners. Fish was a main food, but unlike Germans, Poles usually only ate fish on fast days when the church forbade meat.

Beer was drunk by everyone, no matter their social class. It came in many types and was made from millet, wheat, barley, rye, or oats, sometimes mixed together. Wheat beer was the most common. A herb called Labrador tea was sometimes added to barley and wheat beer to make a "thick beer."

Even though many people think mead was a common Slavic drink, it was quite expensive. It was mostly enjoyed at weddings and baptismal parties, but beer was always more popular. Mead was seen as a special drink for ceremonies, like when making alliances or signing contracts. Wine was usually very expensive and mostly enjoyed by nobles. Although there were a few vineyards in Poland, almost all wine had to be imported.

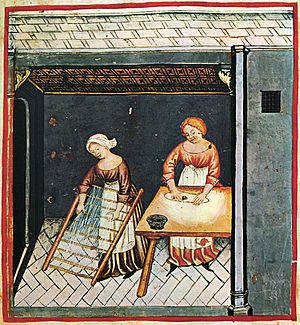

Many kinds of bread were sold in Krakow as early as the 14th century, like obwarzanki. Flat cakes called placki came in many varieties. One type had an apple topping, similar to a pizza. German bakers working in Polish towns had a big influence. Krepels were fried pastries with a cheese filling, served with strawberries or other fruit. They looked like a modern empanada.

Food in Northern Europe

British Cooking

We don't know much about what the Anglo-Saxons ate before the Norman conquest in 1066. Ale was the main drink for both common people and nobles. Known dishes included different stews, simple broths, soups, and a hard pancake-like bread called crumpet. Bacon was also eaten. The cooking was not very fancy, and there wasn't much influence from other countries.

This changed in the 11th century after the Norman invasion. The Normans brought new nobles and new eating habits, especially for the wealthy. While British cooking today isn't always seen as fancy internationally, medieval Anglo-Norman cooks were quite skilled and knew about foods from other places. People used to think Anglo-Norman food was just like French food. But recent studies show that many recipes had unique English touches. This was partly because of the different foods available in the British Isles. It was also due to influence from Arab cuisine through the Norman conquest of Sicily. Arab invaders in the 9th century had a very advanced culture and economy. The Norman invaders learned many of their habits, including cooking styles. Normans also took part in the crusades, which connected them with food from the Middle East and the Byzantine Empire.

English chefs made the subtlety (or entremet) very complex and beautiful. This was a fancy, surprising dish used between courses. One special dish was pommes dorées ("gilded apples"). These were meatballs made of mutton or chicken, colored with saffron or an egg yolk glaze. The Anglo-Norman version, pommes d'orange, were flavored and colored with bitter orange juice.

In the far north of Europe, the climate made it even harder to grow grains. Wheat, which was popular in the south, was a luxury here. Wheat could cost at least twice as much as the most common grains, barley and rye. Barley was grown the most, but much of it went into making a lot of beer. Rye was the main grain for bread. Like in the rest of Europe, oats were mostly seen as animal feed. People only ate oats if they had no other choice, usually as porridge.

Even though grains were highly valued and often mentioned, other vegetables were a key part of the diet. Peas, turnips, beans, carrots, onions, leeks, and various greens and herbs provided important nutrients. Kale, a type of cabbage, was especially important in Denmark and Sweden. It was a valuable source of fresh food in winter because it stored well and tasted even better after the first frost.

Fish was very important to most of Scandinavia. The herring fishing in the Limfjord and Oresund was particularly big. Huge schools of herring swam from the Atlantic into the Baltic Sea. They were caught in massive numbers. There was more than enough fish to feed the local people, and a lot was exported as smoked or, especially, salted fish. Large herring markets were set up in southern Scandinavia, like at Skanör in Scania, which was part of Denmark back then. From this market alone, ships from the Hanseatic League exported over 100,000 barrels of salted herring for many decades in the Late Middle Ages.

Cod was just as important, or even more so. It was often caught in the North Sea and Atlantic, dried to make stockfish, and imported as a key food, especially during fasts and Lent. Many freshwater fish were also important for food or trade, such as salmon, eel, pike, and bream.

Raising cattle was very common in Scandinavia, especially in Denmark. The Black Death had left many fields empty, which were perfect for grazing. Most of the meat produced was eaten by local people. But after the 1360s, a market for high-quality beef slowly grew. By the 17th century, over 100,000 animals were exported each year. All these cattle meant not just meat, but also large amounts of dairy products. These included sour milk drinks, various cheeses, and butter, which was also a major export.

Food in Northern France

Northern French cooking was similar to Anglo-Norman French food across the channel. But it also had its own special dishes. Typical of northern French kitchens were potages and broths. French chefs were excellent at preparing meat, fish, roasts, and the sauces that went with each dish. Using dough and pastry, which was popular in Britain, was almost completely missing from French recipe books, except for a few pies. There were also no dumplings or fritters, which were so popular in Central Europe. A common habit in Northern France was to name dishes after famous and often exotic places or people.

A special skill of fine French chefs was making parti-colored dishes. These copied the late medieval fashion of wearing clothes with two different colors on each side. This style still exists in the costumes of court jesters. The common Western European "white dish" (blanc manger) had a northern French version where one side was bright red or blue. Another recipe from Du fait de cuisine (1420) described an entremet. This was a roasted boar's head with one half colored green and the other golden yellow.

Food in Western Mediterranean

The Roman influence on the entire Mediterranean region was huge. Even today, the basic foods in most of the region are still wheat bread, olives, olive oil, wine, cheese, and some meat or fish. The areas from the Atlantic to the Italian Peninsula, especially where Catalan and Occitan were spoken, were closely connected culturally and politically. The Muslim conquest of Sicily and southern Spain greatly influenced the food. They brought new plants like lemons, pomegranates, eggplants, and spices like saffron. The Arabs also taught Europeans how to color food and many other cooking techniques. These ideas slowly spread to regions further north.

Iberian Cooking (Spain and Portugal)

The Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) has very different landscapes. It has a large, flat central plateau surrounded by mountains. The Pyrenees mountains cut it off from the rest of Europe. This meant that several different cultures lived side-by-side, each with unique foods. Since ancient times, it had been a colony of several Mediterranean cultures. The Phoenicians brought olive growing. The Greeks brought the Malvasia grape, starting a wine industry that became famous in the Middle Ages.

But the Roman Empire had the biggest impact on Iberian food. After the Romans, Visigoth invaders took over most of Spain and Portugal in the 5th century. The Visigoths adopted many Roman customs, like focusing on vegetables. But the invasions by North African Muslims and the creation of Al-Andalus made Iberian food truly unique. The Muslims brought very refined cooking styles influenced by Arab courts in the Middle East.

The new Muslim rulers introduced many new customs and foods. They used goblets made of glass instead of metal. They cooked savory meat dishes with fruit, spices, and herbs like cinnamon, mastic, caraway, sesame, and mint. They liked using ground almonds or rice to thicken dishes. They also enjoyed adding tangy liquids like verjuice, tamarind, and bitter orange juice to create a sweet-sour taste.

You can clearly see the impact in the many Arabic words borrowed into Spanish. Words like naranja ("orange"), azúcar ("sugar"), alcachofa ("artichoke"), azafrán ("saffron"), and espinaca ("spinach") spread to other European languages. Spanish Muslims also set up the order of dishes that spread across Europe. This order, with soup, then meat, then sweets, is still the basis for many modern European meals. It's also thought that escabeche, a vinegar-based dish, might come from Arab-Persian cooking.

One of the earliest medieval cookbooks not in Latin was Libre de Sent Soví ("The Book of Saint Sophia"). It was written in Catalan around 1324. Most of its recipes use bitter oranges, rose water, and cider to get the popular tangy flavor of late medieval food. It has many fish recipes, but surprisingly, no mention of shellfish. Shellfish must have been a major food source in the Catalan coastal areas. The very important Libre del Coch, also in Catalan, was printed in 1520. But it was likely written before 1490.

The typical medieval white dish (manjar blanco) seems to have first appeared in Catalonia in the 8th century. It later became a type of sweet pudding. While not often in cookbooks, the most common foods for regular people were bread, wine, garlic, onion, and olive oil. They also ate eggs, lamb, beef, goat meat, and bacon.

The Jewish people of Al-Andalus, called Sephardic Jews, developed their cuisine while living closely with Christians and Muslims. Their cooking influenced each other, even after Jewish people were expelled or forced to convert after the Reconquista. One special dish was adafina (from Arabic al dafina "the buried treasure"). This meat dish was prepared by burying it in hot coals the day before the Shabbat (Sabbath). Jewish fish pie dishes have survived in Spanish cuisine as empanadas de pescado.

Italian Cooking

The profitable Mediterranean trade in spices, silk, and other luxuries from Africa and Asia made the powerful city-states of Genoa, Venice, and Florence incredibly rich. Medieval Italy, mainly the northern Italian Peninsula, was one of the few places in medieval Europe where the difference between nobles and wealthy commoners didn't matter as much. This was because there was a large, rich, and confident middle class. This meant that the cooking was especially refined and diverse compared to the rest of Europe.

Italian food was, and still is, better described as many different regional cuisines. Each has long traditions and its own special dishes. Italian dishes can be either traditional or imported. Being a center for a huge trade network meant that foreign luxuries were more available to influence local cooking. Still, people were quite traditional. Generally, more local Italian foods were sent to the New World than the other way around. However, important products like vanilla, corn, kidney beans, and of course, the tomato, had a big impact on cooking south of Naples, though this change took some time.

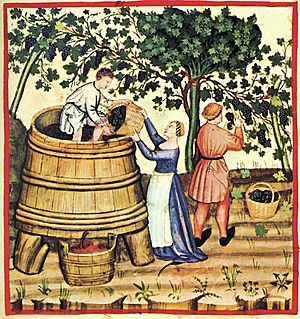

Many Italian staple foods and internationally famous dishes were created and improved during the Late Middle Ages and early Renaissance. Pasta was on everyone's dinner plate by the 13th century, though it was usually made from rice flour instead of durum wheat. Pizza, the medieval Italian word for "pie," and tortes came in many varieties with different toppings. These ranged from marzipan and custards to chicken, eel, or even hemp. Polenta was made from French green lentils or barley. Risotto and many local types of sausage and cheese were eaten by almost everyone.

Even in the Middle Ages, cheeses were very specialized. There was fresh Tuscan cheese and aged Milanese cheese from Tadesca, which was wrapped and shipped in tree bark. Medieval Italians also used eggs more than people in many other regions. Recipe collections describe herb omelets (herboletos) and frittatas. Grapes were eaten as tasty snacks, and lemons were used everywhere in cooking. Of course, olive oil of every kind was the preferred cooking fat in all regions, even the north. It was used for salad dressings, frying, seasoning, marinating, and preserving meats.

Southern French Cooking

The food of southern France, which is roughly the area of Occitania, had much more in common with Italian and Spanish cooking than with northern French food. Ingredients that made southern cooking special included sugar, walnut oil, chickpeas, pomegranates, and lemons. All of these were grown locally. While pomegranate seeds were sometimes used to decorate dishes in France and England, flavoring dishes with pomegranate juice was unique to the Occitan areas.

Using butter and lard was rare. Salted meat for frying was common. The preferred cooking methods were dry roasting, frying, or baking. For baking, a trapa was often used. This was a portable oven filled with food and buried in hot ashes.

Dishes still common today, like escabeche (a vinegar-based dish) and aillade (aioli, a garlic sauce still made in Toulouse with walnut oil), were well-known in the Late Middle Ages. You can see influence from Muslim Spain in recipes for matafeam. This was a Christian version of the Hispano-Jewish Shabbat stew adafina, but with pork instead of lamb. Also, Raymonia (Occitan; Italian: Romania) is based on the Arabic Rummaniya, a chicken stew with pomegranate juice, ground almonds, and sugar.

Only one recipe collection is definitely from southern France. It's called Modus viaticorum preparandorum et salsarum and has 51 recipes. It was written around 1380–90 in Latin with some Occitan words. The Modus contains a Salsa de cerpol (Wild thyme sauce) and a Cofiment anguille (Confit of eel), which are only found in Occitania.

Some details about what people ate have been found from Vatican records from 1305–78. During this time, Avignon was the home of the Avignon Papacy. Even though the papal courts often lived very luxuriously, the Vatican's records of daily alms (charity) given to the poor show what lower-class food in the region was like. The food given to those in need was mainly bread, legumes, and some wine. Sometimes, they also received cheese, fish, olive oil, and low-quality meat.

Montpellier, located in Languedoc near the coast, was a major center for trade and medical education. It was famous for its espices de chamber or "parlor confections." This term referred to sweets like candied aniseed and ginger. The sweets from Montpellier were so well-known that their value was twice as high as similar products from other towns. Montpellier was also known for its spices and the wines flavored with them, like the popular hypocras.

Byzantine Empire Food

The cooking traditions from Roman times continued in the Byzantine empire. From Greek traditions, they used olives and olive oil, wheat bread, and lots of fish. These were often served or prepared with garós, the Greek name for garum. This was a sauce made from fermented fish that was so popular it almost replaced salt as the main food flavoring.

Byzantine cooking was also influenced by Arab cuisine. From them, they started using eggplants and oranges. Seafood was very popular and included tuna, lobster, mussels, oysters, murena, and carp. Around the 11th century, eating roe and caviar also became popular, imported from the Black Sea region.

Dairy products were eaten as cheese (especially feta). Nuts and fruits like dates, figs, grapes, pomegranates, and apples were also common. Meats included lamb and several wild animals like gazelles and wild asses. Young animals were also eaten. Meat was often salted, smoked, or dried.

Wine was popular, like elsewhere around the Mediterranean. It was the drink of choice among the higher social classes, where sweet wines like Muscat were popular. Among the lower classes, the common drink was usually vinegar mixed with water. Like all Christian societies, the Byzantines had to follow the food rules of the church. This meant avoiding meats (and generally not overeating) on Wednesdays and Fridays, and during fast and Lent.

The Byzantine empire also became famous for its desserts. These included biscuits, rice pudding, quince marmalade, rose sugar, and many types of non-alcoholic beverages. The most common sweetener was honey. Sugar from sugar cane was only for those who could afford it.

The food of the lower classes was mostly vegetarian. It was limited to olives, fruit, onions, and an occasional piece of cheese. They also ate stews made from cabbage and salted pork. A Byzantine poem described the standard meal of a shoemaker. It included some cooked foods and an omelet, followed by hot salted pork with an unspecified garlic dish.