History of Buddhism facts for kids

|

Basic terms |

|

|

People |

|

|

Schools |

|

|

Practices |

|

|

study Dharma |

|

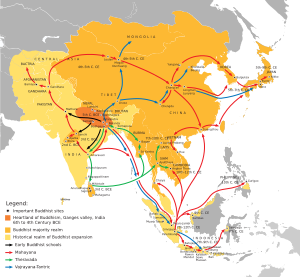

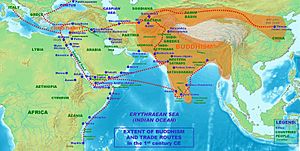

The history of Buddhism began around 2,500 years ago. It started in Ancient India and is based on the teachings of a wise man named Siddhārtha Gautama. This religion grew and spread from India across Central, East, and Southeast Asia. Over time, it touched many parts of Asia.

Buddhism's story also includes the rise of different groups and ideas. Some important traditions are Theravāda, Mahāyāna, and Vajrayāna. These traditions grew and changed as Buddhism spread and sometimes faced challenges.

Contents

- The First Buddha: Siddhartha Gautama (5th Century BCE)

- Early Buddhist Communities and Councils

- Buddhism Under the Mauryan Empire (322–180 BCE)

- The Rise of Mahāyāna Buddhism

- Buddhism Under the Shunga Dynasty (2nd–1st Century BCE)

- Greco-Buddhism: Where East Met West

- Kushan Empire and Gandharan Buddhism

- Buddhism Spreads to Central Asia

- Buddhism in India: Gupta and Pāla Eras

- East Asian Buddhism

- Southeast Asian Buddhism

- Buddhism in the Modern World

- See also

The First Buddha: Siddhartha Gautama (5th Century BCE)

Siddhārtha Gautama is the person who started Buddhism. He lived about 2,500 years ago. Early stories say he was born in a small republic called Shakya, which is now part of Nepal. That's why he is also known as Shakyamuni, meaning "the wise one from the Shakya clan."

Ancient texts don't give a full life story of the Buddha. But they all agree that Gautama left his home life. He became an ascetic, meaning he lived a very simple life. He studied with different teachers. Finally, he found nirvana (peace) and bodhi (awakening) through deep meditation.

For the next 45 years, he traveled and taught his ideas. He taught people from all walks of life in north-central India. He also started groups for monks and nuns. The Buddha encouraged his followers to teach in local languages. By the time he passed away at 80, he had thousands of followers.

Early Buddhist Communities and Councils

After the Buddha's death, the Buddhist community, called the sangha, stayed in the Ganges valley. It slowly spread from there. Old writings tell of meetings, called councils. Here, monks would recite and organize the Buddha's teachings. They also discussed rules for the community. Some modern experts question if all these council stories are completely true.

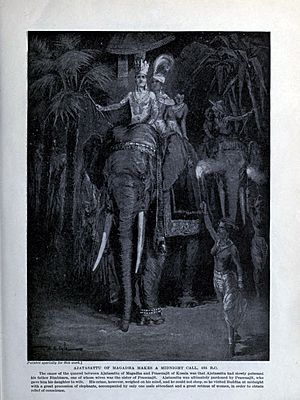

The first Buddhist council is said to have happened right after the Buddha's death. It was led by Mahākāśyapa, one of his main students. It took place in Rājagṛha with support from King Ajātasattu. Many scholars today doubt if this first council truly happened as described.

Buddhism Under the Mauryan Empire (322–180 BCE)

-

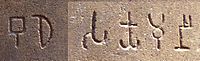

The words "Bu-dhe" and "Sa-kya-mu-nī" in Brahmi script, on Ashoka's Lumbini pillar inscription (around 250 BCE).

-

A piece of the 6th Pillar Edict of Aśoka (238 BCE), in Brāhmī. British Museum.

-

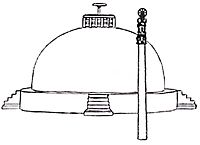

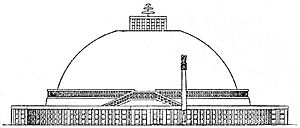

A possible look of the Great Stupa with Ashoka Pillar, Sanchi, India.

The Sangha Divides: Second Buddhist Council

After a time of unity, the Buddhist community started to divide. This led to the first big split into two groups: the Sthavira (Elders) and Mahasamghika (Great Sangha). Most experts agree this split happened because of disagreements about monastic rules. Over time, these two groups divided even more into different Early Buddhist Schools.

Many scholars believe the first major split happened during the rule of Emperor Ashoka. The Theravada tradition says the split happened at the Second Buddhist council in Vaishali. This was about 100 years after the Buddha's death. While the second council likely happened, the stories about it are a bit confusing.

The Sthavira group led to many important schools, like the Sarvāstivāda and the Theravādins. The Mahasamghikas also formed their own schools and ideas. One of their schools, the Lokottaravāda, believed that all of Gautama Buddha's actions were "supernatural," even before he became a Buddha. This idea hinted at some later Mahayana teachings.

Around 300 BCE, some Buddhists started new detailed teachings called Abhidharma. These were based on lists of main ideas. Unlike the Buddha's simple talks, Abhidharma writings were very systematic. Different schools often disagreed on these points. Abhidharma tried to break down all experiences into tiny parts called dharmas. These texts helped create different Buddhist identities. The splits in the monastic community were first about rules, but later, around 100 CE, they were also about different ideas. Not all early schools developed Abhidharma texts.

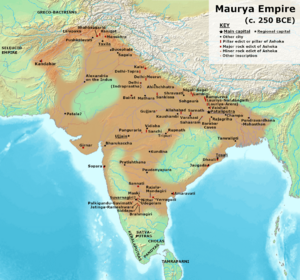

Ashoka's Buddhist Missions

During the rule of the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka (268–232 BCE), Buddhism received royal support. This helped it spread widely across India. After a war, Ashoka felt regret. He then worked to improve his people's lives. Ashoka built wells, rest-houses, and hospitals for people and animals. He also stopped torture and royal hunting trips. Ashoka supported other religions too, like Jainism and Brahmanism. He spread Buddhism by building stupas (mounds containing relics) and pillars. These urged people to respect all life and follow the Dharma (Buddhist teachings). He is seen as a great, compassionate ruler in Buddhist stories.

People believed that showing devotion to these relics and stupas could bring good fortune. The Great Stupa of Sanchi (from the 3rd century BCE) is a well-preserved example of a Mauryan Buddhist site.

Ashoka's pillars and plates, known as the Edicts of Ashoka, say he sent messengers to many countries to spread Buddhism. They went as far south as Sri Lanka and as far west as Greek kingdoms, possibly even to the Mediterranean.

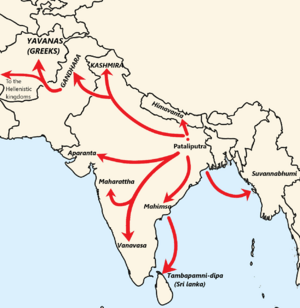

Third Buddhist Council and Missions to the West

Theravadin sources say that Ashoka held the third Buddhist council around 250 BCE. It was in Pataliputra (modern Patna) and led by the elder Moggaliputtatissa. The goal was to purify the Buddhist community, especially from non-Buddhist ascetics who were joining for royal support. After the council, Buddhist missionaries were sent across the known world, as Ashoka's edicts show.

Some of Ashoka's edicts describe his efforts to spread Buddhism in the Greek world. This area stretched from India to Greece. The edicts show Ashoka understood the Greek kingdoms well. He named their kings, like Antiochus II Theos of the Seleucid Kingdom and Ptolemy II Philadelphos of Egypt. He claimed they received Buddhist teachings. One edict says:

- "The conquest by Dharma has been won here, on the borders, and even six hundred yojanas away, where the Greek king Antiochos rules, beyond there where the four kings named Ptolemy, Antigonos, Magas and Alexander rule, likewise in the south among the Cholas, the Pandyas, and as far as Tamraparni (Sri Lanka)." (Edicts of Aśoka, 13th Rock Edict, S. Dhammika).

Some of Ashoka's messengers were Greek, like one named Dhammarakkhita. Ashoka even issued edicts in Greek. One found in Kandahar encouraged the Greek community to adopt "piety" (using the Greek word eusebeia for Dharma).

It's not clear how much these interactions influenced Western thought. But some writers believe Buddhism might have had an impact. There were Buddhist communities in the Greek world, for example, in Alexandria. Some thinkers, like Pyrrho, are thought to have been influenced by Buddhist ideas.

Buddhist gravestones with Dharma wheels have been found in Alexandria. This suggests Buddhists were present there. Some even think they influenced early Christian monasticism.

Buddhism Comes to Sri Lanka

Sri Lankan stories say that Ashoka's son Mahinda brought Buddhism to the island in the 2nd century BCE. Ashoka's daughter, Saṅghamitta, also started the order for nuns in Sri Lanka. She brought a sapling from the sacred bodhi tree (where Buddha found enlightenment). This tree was planted in Anuradhapura. These two are seen as the founders of Sri Lankan Theravada Buddhism. They are said to have converted King Devanampiya Tissa and many nobles.

The first images of Buddha in architecture appeared later, during King Vasabha's rule (65–109 CE). Important Buddhist monasteries in ancient Sri Lanka included Mahāvihāra, Abhayagiri, and Jetavana. The Pāli canon, a complete collection of Buddhist texts, was written down in the 1st century BCE. This was done to save the teachings during a time of war and hunger. It reflects the traditions of the Mahavihara school.

Later, Mahāyāna Buddhism gained some influence in Sri Lanka. It was studied at Abhayagiri and Jetavana. However, the Mahavihara school became the most powerful in Sri Lanka after King Parakramabahu I (1153–1186) ended the Abhayagiri and Jetavanin traditions.

The Rise of Mahāyāna Buddhism

The Buddhist movement called Mahayana (meaning "Great Vehicle") began between 150 BCE and 100 CE. It grew from ideas in both the Mahasamghika and Sarvastivada groups. The earliest clear Mahayana writing is from 180 CE in Mathura.

Mahayana focused on the Bodhisattva path. A Bodhisattva is someone who delays their own enlightenment to help all beings. This was different from the goal of becoming an arhat (a fully enlightened person who reaches nirvana). Mahayana started with new texts called the Mahayana sutras. These sutras taught new ideas, like that "there are other Buddhas teaching in countless other worlds." Over time, Mahayana Bodhisattvas and many Buddhas became seen as powerful, kind beings to be worshipped.

For a while, Mahayana was a smaller group among Indian Buddhists. It grew slowly. By the 7th century, about half of the monks met by the Chinese traveler Xuanzang in India were Mahayanists. Early Mahayana ideas included Mādhyamaka, Yogācāra, and Buddha-nature teachings. Today, Mahayana is the main form of Buddhism in East Asia and Tibet.

Some scholars think the Prajñāpāramitā sūtras, which are very early Mahayana texts, developed among the Mahasamghika group in southern India.

Buddhism Under the Shunga Dynasty (2nd–1st Century BCE)

The Shunga dynasty (185–73 BCE) began about 50 years after Ashoka's death. The military commander Pushyamitra Shunga took the throne after killing the last Mauryan ruler. Some Buddhist writings claim Pushyamitra was against Buddhists and harmed them. They say he destroyed many monasteries and killed monks.

However, modern historians disagree with this. They say there's no real proof of active persecution. While Buddhist institutions might have faced harder times after Ashoka's support, there's no evidence of widespread destruction. Historians believe the Buddhist stories might have exaggerated Pushyamitra's actions. They likely show the frustration of Buddhists as their religion became less important under the Shungas.

During this time, Buddhist monks left the Ganges valley. They moved to the northwest (like Gandhara and Mathura) or the southeast (around Amaravati Stupa). Buddhist art also moved to these new areas.

Greco-Buddhism: Where East Met West

The Greek king Demetrius I invaded India around 200 BCE. He set up an Indo-Greek kingdom in parts of Northwest South Asia. This kingdom lasted until the end of the 1st century CE.

Buddhism thrived under these Greek kings. One famous Indo-Greek king was Menander (around 160–135 BCE). He might have become a Buddhist. Buddhist stories see him as a great supporter of the faith, like King Ashoka. Menander's coins show the eight-spoked Dharmachakra (dharma wheel), a classic Buddhist symbol.

A famous book called the Debate of King Milinda (Milinda Pañha) tells of a discussion between Menander and the Buddhist monk Nāgasena. Nagasena was a student of a Greek Buddhist monk. When Menander died, cities under his rule wanted to share his remains, placing them in stupas, just like the Buddha. Some of Menander's successors even put "Follower of the Dharma" on their coins.

The first human-like statues of the Buddha appeared in these Greek-ruled lands around the 1st century BCE. They had a realistic style called Greco-Buddhist. Many features of these Buddha statues show Greek influence. For example, the toga-like robe, the standing pose, the curly hair, and the realistic faces. Many sculptures mixing Buddhist and Greek styles were found at Hadda.

Several important Greek Buddhist monks are mentioned. Mahadharmaraksita was a "Greek Buddhist head monk" who led 30,000 monks to Sri Lanka. Dhammarakkhita was another Greek missionary sent by Emperor Ashoka.

Kushan Empire and Gandharan Buddhism

The Kushan empire (30–375 CE) was formed by nomads in the 1st century BCE. It covered much of northern India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. The Kushans adopted parts of Greek culture. Under their rule, Gandharan Buddhism became very strong. Many Buddhist centers were built or fixed up.

Kushan Buddhist art in Gandhara mixed Greek, Roman, Iranian, and Indian styles. The oldest Buddhist writings found (around 1st century CE) are from this period. They are mostly from the Dharmaguptaka school.

Emperor Kanishka (128–151 CE) was a big supporter of Buddhism. During his rule, stupas and monasteries were built in his capital city, Peshawar. Kushan royal support and new trade routes helped Gandharan Buddhism spread along the Silk Road to Central Asia and China.

Kanishka is also said to have held a big Buddhist council for the Sarvastivada tradition. Here, 500 monks worked to create detailed commentaries on the Abhidharma. The main result was a huge book called the Mahā-Vibhāshā. Some modern scholars question if this traditional story is entirely true.

Around this time, the Sarvastivada texts were changed from an older language to Sanskrit. This was important because Sanskrit was a sacred language in India. It allowed more people to access Buddhist ideas.

After the Kushans fell, the Hephthalite White Huns took over the area (around 440s–670). Buddhism continued to thrive in cities like Balkh, as noted by Xuanzang in the 7th century. He saw many monasteries and monks there. After the Hephthalite empire ended, Gandharan Buddhism declined in the main Gandhara area. But it continued in nearby places like the Swat Valley, Kashmir, and Afghanistan.

Buddhism Spreads to Central Asia

Central Asia was home to the Silk Road, a major trade route connecting China, India, and the Middle East. Buddhism was present here from about the 2nd century BCE. The Dharmaguptaka school was very successful in spreading Buddhism in Central Asia. The Kingdom of Khotan was an early Buddhist kingdom that helped bring Buddhism from India to China.

The Kushan empire united much of this area and supported Buddhism. This allowed it to spread easily along the trade routes. During the 1st century CE, the Sarvastivada school grew here. Some monks also brought Mahayana teachings. Buddhism reached modern-day Pakistan, Kashmir, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan. As Buddhism arrived, texts were translated into local languages like Khotanese and Sogdian.

Central Asians were key in bringing Buddhism to China. The first translators of Buddhist scriptures into Chinese were from Iran. The Zoroastrian Sassanian empire (226–651 CE) later ruled many of these regions but tolerated Buddhism.

However, in the mid-7th century, Arab conquests and the rise of the Ghaznavid kingdom led to Buddhism disappearing from most of these areas.

Buddhism also flourished in eastern Central Asia, like the Tarim Basin. This region has rich Buddhist art and texts, such as those found in Dunhuang. The Uyghurs conquered the area in the 8th century. They blended with local people and adopted the Buddhist culture. Uyghur Buddhism was the last major Buddhist culture in Xinjiang. It lasted until the mid-14th century. After the area became Islamic, Buddhism was no longer a major religion there.

Buddhism in India: Gupta and Pāla Eras

-

Ruins of the Buddhist Nālandā complex, a major learning center in India from the 5th century CE to about 1200 CE.

-

The current structure of the Mahabodhi Temple at Bodh Gaya is from the Gupta era, 5th century CE.

-

"King Harsha pays homage to Buddha", a 20th-century artist's imagination.

Buddhism continued to do well in India during the Gupta Empire (4th–6th centuries). Gupta rulers like Kumaragupta I supported Buddhism. He expanded Nālandā university, which became India's largest and most important Buddhist university for centuries. Great Buddhist thinkers taught philosophy there.

Another major Buddhist university was Valabhi in western India. It was second only to Nalanda in the 5th century. It focused on non-Mahayana Buddhism but also taught many other subjects.

The Gupta style of Buddhist art spread with the faith to Southeast Asia and China. During this time, Chinese pilgrims visited India to study Buddhism.

One pilgrim, Faxian, visited in 405 CE. He noted how prosperous and well-governed the Gupta empire was. Another Chinese traveler, Xuanzang, visited in the 7th century. He reported that Buddhism was popular in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. While he saw many empty stupas in Nepal and persecution in Bengal, he praised Emperor Harṣavardana's support. Xuanzang also noted that Buddhism was losing ground to Jainism and Hinduism in some areas.

After Harsha's empire fell, many small kingdoms fought in the Gangetic plain. This lasted until the Pāla Empire (8th–12th centuries) rose in Bengal. The Pālas strongly supported Buddhism. They built important Buddhist centers like Vikramashila, Somapura, and Odantapuri. They also supported older centers like Nalanda. At these centers, scholars developed Vajrayana philosophy and studied many other subjects. Under the Pālas, Vajrayana Buddhism spread to Tibet, Bhutan, and Sikkim.

A big moment in the decline of Indian Buddhism in the North happened in 1193. Turkic Islamic raiders burned Nālandā. By the late 12th century, after Islamic conquests and loss of political support, Buddhism moved to the Himalayan foothills and Sri Lanka. Also, Hinduism's revival movements and the rise of the bhakti movement lessened Buddhism's influence.

Vajrayāna Buddhism

Under the Gupta and Pala empires, a new Buddhist movement appeared. It was called Vajrayāna, Mantrayāna, or Tantric Buddhism. It brought new practices like using mantras (sacred sounds), mudras (hand gestures), and mandalas (symbolic diagrams). It also involved visualizing deities and Buddhas. This movement created a new type of literature called the Buddhist Tantras. It started with wandering yogis called mahasiddhas.

Vajrayana literature developed as royal courts supported both Buddhism and Shaivism (a Hindu tradition). Some Vajrayana texts even suggested that mantras from Hindu traditions could work for Buddhists. This shows how some Buddhist and Hindu practices mixed during this time.

Tibetan Buddhism

Buddhism arrived in Tibet later, in the 7th century. The form that became popular was a mix of mahāyāna and vajrayāna from the Pāla empire in eastern India. Ideas from the Sarvāstivādin school came from Kashmir and Khotan. Their texts became part of the Tibetan Buddhist canon. A part of this school, Mūlasarvāstivāda, provided the rules for Tibetan monks. Chan Buddhism from China also made an impression but became less important early on.

At first, Buddhism faced opposition from the local shamanistic Bon religion. But with royal support, it grew strong under King Rälpachän (817–836). Translation of texts was standardized around 825. Even though Buddhist influence declined under King Langdarma (836–842), the next centuries saw a huge effort to collect Indian Buddhist texts. Many of these now only exist in Tibetan translation. Tibetan Buddhism was favored by the rulers of the Chinese and Mongol Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368).

East Asian Buddhism

Buddhism in China

-

Extent of the Han Empire.

-

Manjusri Bodhisattva debates Vimalakirti. Scene from the Vimalakirti Nirdesa Sutra. Dunhuang, Mogao Caves, China, Tang Dynasty.

-

Giant Wild Goose Pagoda in Xi'an, 704 CE.

Buddhism came to China during the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), around 50 CE. But it really grew during the Six Dynasties period (220–589 CE). The first Buddhist texts translated into Chinese were by a Parthian monk named An Shigao (148–180 CE). Early translators found it hard to explain Buddhist ideas to the Chinese. They often used Taoist words to help. Later translators, like Kumārajīva (334–413 CE), greatly improved the translations.

Some of the earliest Buddhist art in China are small statues from around 200 CE. Between 460 and 525 CE, during the Northern Wei dynasty, the Chinese built the impressive Yungang Grottoes and Longmen Grottoes with huge sculptures. In the 5th century, Chinese Buddhists also developed new schools, like the Tiantai school and Chan Buddhism.

Buddhism continued to grow during the early Tang Dynasty (618–907). During this time, the Chinese monk Xuanzang traveled to India. He brought back 657 Buddhist texts, relics, and statues. He set up a famous translation school in the capital city of Chang'an (now Xi'an). Also, Chinese Esoteric Buddhism came from India. The Tang dynasty also saw the rise of Chan Buddhism (Zen). However, in the later Tang, Chinese Buddhism suffered during the Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution of 845.

Buddhism recovered during the Song Dynasty (960–1279). This time is known as the "golden age" of Chan. Chinese Chan influenced Korean and Japanese Buddhism. Pure Land Buddhism also became popular. During the Song, the entire Chinese Buddhist canon was printed using over 130,000 wooden blocks.

During the Yuan Dynasty, Tibetan Buddhism became the state religion. In the Ming (1368–1644), the Chan school became the main tradition. In the 17th century, Buddhism spread to Taiwan with Chinese immigrants.

Buddhism in Vietnam

It's not fully agreed when Buddhism arrived in Vietnam. It might have come as early as the 3rd or 2nd century BCE from India, or in the 1st or 2nd century CE from China. Either way, Mahayana Buddhism was present by the 2nd century CE. By the 9th century, both Pure Land and Thien (Zen) were major Vietnamese Buddhist schools. In the southern Kingdom of Champa, Hinduism, Theravada, and Mahayana were practiced. After an invasion in the 15th century, Chinese forms of Buddhism became dominant. However, Theravada Buddhism still exists in southern Vietnam. Vietnamese Buddhism is very similar to Chinese Buddhism. It also mixes with Taoism, Chinese spirituality, and local Vietnamese beliefs.

Buddhism in Korea

Buddhism was introduced to the Three Kingdoms of Korea around 372 CE. In the 6th century, many Korean monks traveled to China and India to study. Various Korean Buddhist schools developed. Buddhism thrived in Korea during the North–South States Period (688–926), becoming very important in society. It remained popular in the Goryeo period (918–1392), especially Seon (Zen) Buddhism. However, during the Confucian Yi Dynasty of the Joseon period, Buddhism faced difficulties. Monastery lands were taken, monasteries closed, and nobles were banned from becoming monks in the 15th century.

Buddhism in Japan

Buddhism came to Japan in the 6th century. Korean monks brought sutras and a Buddha image. During the Nara Period (710–794), Emperor Shōmu ordered temples built across his land. Many temples were built in the capital city of Nara, like the Hōryū-ji and Kōfuku-ji temples. Many Buddhist groups also appeared in Nara. The most important was the Kegon school.

Later in the Nara period, Kūkai (774–835) and Saichō (767–822) founded the influential Japanese schools of Shingon and Tendai. A key idea for these schools was hongaku (innate awakening). This idea influenced all later Japanese Buddhism. Buddhism also affected the Japanese religion of Shinto, which took in Buddhist elements.

During the later Kamakura period (1185–1333), six new Buddhist schools were founded. These were called "New Buddhism." They included the important Pure Land schools of Hōnen and Shinran. Also, the Rinzai and Soto schools of Zen were founded by Eisai and Dōgen. The Lotus Sutra school was founded by Nichiren.

Japanese Buddhist art was very active between the 8th and 13th centuries. Buddhism, especially Zen, remained important during the Ashikaga period (1333–1573) and the Tokugawa era (1603–1867).

Buddhism in Mongolia

The rulers of nomadic empires like the Xiongnu and Göktürks welcomed Buddhist missionaries and built temples. Buddhism was popular among nobles and supported by the rulers of the Northern Wei dynasty and the Liao dynasty.

Genghis Khan (around 1162 - 1227) and his followers conquered much of Asia. The emperors of the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368) in the 13th and 14th centuries converted to Tibetan Buddhism. The founder, Kublai Khan, invited lama Drogön Chögyal Phagpa to spread Buddhism. Buddhism became the main religion of the Yuan dynasty. In 1269, Kublai Khan asked Phagpa lama to create a new writing system for the empire. This script was based on Tibetan and used for many languages. The Mongols helped the Sakya school and then the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism grow.

The Mongols returned to shamanic traditions after the Yuan dynasty fell in 1368.

In 1578, Altan Khan, a Mongol leader, invited the 3rd Dalai Lama, the head of the Gelug lineage. They formed an alliance. Altan Khan recognized Sonam Gyatso lama as a reincarnation of Phagpa lama and gave him the title of Dalai Lama ("Ocean Lama"). Sonam Gyatso, in turn, recognized Altan as a reincarnation of Kublai Khan. This helped both leaders. After this meeting, the heads of the Gelugpa school became known as Dalai Lamas.

Altan Khan died soon after, but Gelug Buddhism spread throughout Mongolia in the next century.

Southeast Asian Buddhism

Since around 500 BCE, Indian culture influenced Southeast Asian countries. Trade routes linked India with the region. Both Hindu and Buddhist beliefs became important. For over a thousand years, Indian influence brought cultural unity to the region. Languages like Pāli and Sanskrit, along with Theravāda and Mahāyāna Buddhism, were brought from India.

From the 5th to the 13th centuries, Southeast Asia had powerful states that promoted Buddhism and Buddhist art alongside Hinduism. The main Buddhist influence came by sea from India. These empires mostly followed the Mahāyāna faith. Examples include kingdoms like Funan, the Khmer Empire, and the Thai kingdom of Sukhothai. Island kingdoms like Srivijaya and Mataram also promoted Buddhism.

Buddhist monks traveled to China from the kingdom of Funan in the 5th century CE. They brought Mahayana texts, showing Buddhism was already there. Mahayana Buddhism and Hinduism were the main religions of the Khmer Empire (802–1431). Under the Khmer, many Hindu and Buddhist temples were built in Cambodia and Thailand. One great Khmer king, Jayavarman VII (1181–1219), built large Mahāyāna Buddhist structures at Bayon and Angkor Thom.

In the Indonesian island of Java, Indianized kingdoms like the Kalingga Kingdom (6–7th centuries) were places where Chinese monks sought Buddhist texts. The Malay Srivijaya (650–1377), an empire based on Sumatra, adopted Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna Buddhism. They spread Buddhism to Java and other regions.

The Chinese Buddhist Yijing described Srivijaya's capital as a great center of Buddhist learning. The emperor supported over a thousand monks. Yijing advised future Chinese pilgrims to spend time there. Atiśa studied there before going to Tibet. As Srivijaya grew, Buddhism thrived. It also mixed with other religions like Hinduism.

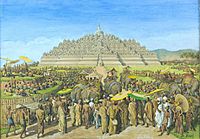

In Java, the Mataram Kingdom (732–1006) also promoted Mahayana Buddhist culture. They are known for huge temples like Borobudur, Kalasan, and Prambanan. Indonesian Buddhism, along with Hinduism, continued under the Majapahit Empire (1293–1527). But it was later replaced by Islam.

-

A painting by G.B. Hooijer (around 1916–1919) showing Borobudur in its prime.

The Theravāda Revival

Evidence shows Theravada Buddhism was present in Myanmar and Thailand from the 5th century CE. Theravada Buddhism in Burma first existed alongside other forms of Buddhism. After Buddhism declined in India, Theravada monks from Sri Lanka spread their teachings to Burma, Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos. They successfully converted these regions to Theravada Buddhism.

King Anawrahta (1044–1078), who founded the Pagan Empire, adopted Theravādin Buddhism from Sri Lanka. He built many Buddhist temples in his capital, Pagan. Invasions weakened Theravada here, and it had to be brought back from Sri Lanka. During the Mon Hanthawaddy Kingdom (1287–1552), Theravada Buddhism was the main religion in Burma. One king, Dhammazedi, is known for reforming Burmese Buddhism based on the Sri Lankan tradition. Theravada remained the official religion of the later Burmese Taungoo Dynasty (1510–1752).

During the reign of the Khmer King Jayavarman VII (around 1181–1218), Theravada Buddhism was promoted by the royal family and Sri Lankan monks. By the 13th and 14th centuries, Theravada became the main religion of Cambodia. Monasteries replaced local priests. The Theravāda faith was also adopted by the Thai kingdom of Sukhothai as the state religion during King Ram Khamhaeng's reign. Theravāda Buddhism was further strengthened during the Ayutthaya period (14th–18th century), becoming a key part of Thai society.

Buddhism in the Modern World

The modern era brought new challenges for Buddhism. Western countries colonized many Buddhist Asian nations. This weakened the traditional political systems that supported the religion. Christianity also brought criticism and competition. Modern wars, communist anti-religious pressure, the growth of capitalism, science, and political instability also affected Buddhism.

Buddhism in South and Southeast Asia Today

-

The Sixth Buddhist council. Mahasi Sayadaw asked questions about the Dhamma, and Mingun Sayadaw answered them.

-

Deekshabhoomi monument, in Nagpur, Maharashtra. B. R. Ambedkar converted to Buddhism here in 1956. It is the largest stupa in Asia.

In British Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Christian missionaries ran schools and criticized Buddhist beliefs. By 1865, Buddhist monks started fighting back. They printed pamphlets and debated Christians in public. A famous debate in 1873 saw the monk Gunananda win in front of a huge crowd.

During this time, a new kind of Buddhism emerged, called Buddhist modernism. It saw the Buddha as a humanist and claimed Buddhism was logical and scientific. Important figures included American convert Henry Olcott and Anagarika Dharmapala. They promoted Buddhist schools and organizations. Dharmapala also founded the Mahā Bodhi Society to restore the ancient site of Bodh Gaya in India. He also traveled to the UK and US to teach Buddhism.

This society helped bring a revival of Buddhism in India. Buddhism became popular among some Indian thinkers. One was the lawyer B. R. Ambedkar (1891–1956). He led the Dalit Buddhist movement and encouraged low-caste Indians to convert to Buddhism.

In Burma, a key modern figure was King Mindon (r. 1853–1878). He held the 5th Buddhist council (1868–71). Here, different versions of the Pali Canon were checked. A final version was carved on 729 stone slabs, which is still the world's largest book. A new meditation movement, called the Vipassana movement, also began in Burma. In 1956, Burmese politician U Nu led a sixth council. Monks from different Theravada countries produced another new edition of the Pali Canon. Recently, Buddhist monks have been involved in political protests.

Thailand was the only country to avoid colonization. It had two important Buddhist kings, King Mongkut and his son King Chulalongkorn. They pushed for modernization and reforms in the Buddhist community.

From 1893, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos were French colonies. Communists took power in Laos in 1975. They tried to control the Buddhist community. In Cambodia, the communist Khmer Rouge (1975–79) caused great harm to the Buddhist community.

Buddhism in East Asia Today

The opening of Japan in 1853 and the Meiji Restoration of 1868 led to the end of feudal Japan and quick modernization. A new form of State Shinto became a strong competitor to Buddhism. The Japanese government adopted it. In 1872, the government allowed Buddhist clerics to marry. These changes led to modernization efforts by Japanese Buddhism. They set up publishing houses and studied Western philosophy. After the war, new Japanese religions appeared, many influenced by Buddhism.

Chinese Buddhism suffered much during the Christian-inspired Taiping rebellion (1850–64). But it saw a small revival during the Republican period (1912–49). A key figure was Taixu (1899–1947), linked to the Humanistic Buddhism trend. The Communist Cultural Revolution (1966–76) closed all Buddhist monasteries and destroyed many institutions. However, since 1977, the communist government's policy has changed. Buddhist activity has started again.

Korean Buddhism faced challenges during Japanese invasions, occupation, and the Korean war. North Korea's government offers limited support but controls all activity. In South Korea, Buddhism revived. Youth groups became important, and temples were rebuilt with government help.

Buddhism in Central Asia Today

Tibet was a traditional state led by the Dalai Lamas from 1912 until the Chinese communist invasion in 1950. The 14th Dalai Lama fled in 1959. A Tibetan exile community was set up in India, with its center in Dharamsala. This is now a center for studying Tibetan Buddhism. The 14th Dalai Lama has become one of the most popular Buddhist leaders worldwide.

During the Red Guard period (1966–67), Chinese communists destroyed about 6,000 monasteries in Tibet. They tried to wipe out Tibetan Buddhist culture. After 1980, Chinese repression decreased. The Tibetan Canon is being reprinted, and some art is being restored. In nearby Bhutan and Nepal, Vajrayana Buddhism continues to thrive.

In Mongolia, which also has Tibetan Buddhism, communist rule (1924–1990) saw much repression. However, Buddhism is now reviving in post-communist Mongolia. There are more monks and nuns, and more monasteries. Liberal attitudes towards religion have also helped Buddhists in Tuva and Buryatia, and in the Chinese region of Inner Mongolia.

Another modern development was the founding of the Kalmyk Khanate in the 17th century, with Tibetan Buddhism as its main religion. They were later absorbed by the Russian Empire as Kalmykia, which is now a part of Russia with a Buddhist majority.

Buddhism in the Western World

In the 19th century, Western thinkers learned more about Buddhism through colonial officials and missionaries. Sir Edwin Arnold's poem The Light of Asia (1879), about the Buddha's life, was a popular early book. It sparked much interest among English speakers. The work of Western Buddhist scholars also helped introduce Buddhism to Western audiences.

The late 19th century saw the first known Westerners convert to Buddhism. This included Theosophists Henry Steel Olcott and Helena Blavatsky in Sri Lanka in 1880. The Theosophical Society helped popularize Indian religions in the West. The 19th century also saw the first Western monks.

Another important reason for Buddhism's growth in the West was the large immigration of Chinese and Japanese people to the United States and Canada in the late 19th century. Refugees from Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia also came to the West after 1975. Asian Buddhists like DT Suzuki and Thích Nhất Hạnh were important in teaching Zen Buddhism in the West in the 20th century.

The Tibetan diaspora has also actively promoted Tibetan Buddhism in the West. All four major Tibetan Buddhist schools are present in the West and have attracted Western converts.

The Theravada tradition has built temples in the West, especially for immigrant communities. Theravada vipassana meditation was also established in the West. The Thai forest tradition has also set up communities in the US and UK. In the UK, the Triratna Buddhist Community emerged as a new modern Buddhist movement.

In Continental Europe, interest in Buddhism also grew in the late 20th century. There was a big increase in Buddhist groups in countries like Germany. In France and Spain, Tibetan Buddhism is most popular. Tibetan, East Asian, and Theravada traditions are now active in Australia and New Zealand. Tibetan and Zen Buddhism also have a small presence in South America.

The spread of Buddhism to the West in the 20th century has made it a worldwide religion.

See also

In Spanish: Historia del budismo para niños

In Spanish: Historia del budismo para niños

- Greater India

- History of India

- History of Yoga

- Indian religions

- Indosphere

- Index of Buddhism-related articles

- Religion in India

- Timeline of Buddhism

- Annexation of Tibet by the People's Republic of China

- Ordination of women in Buddhism

- Secular Buddhism

- Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

- List of Buddhist Kingdoms and Empires