Italian literature facts for kids

Italian literature is writing created in the Italian language, especially within Italy. It can also include works by Italians or in other languages spoken in Italy, like regional dialects. Italian literature began in the 12th century. This is when people in different parts of Italy started using their local Italian dialects for writing stories and poems. The Ritmo laurenziano is the oldest known example of Italian literature.

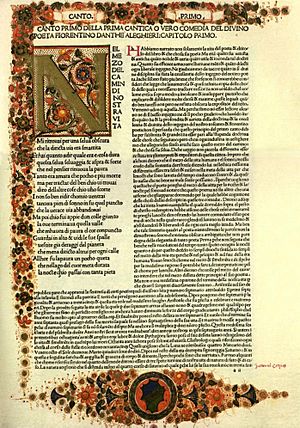

An early form of Italian writing was lyric poetry in the Occitan language. This style arrived in Italy by the late 12th century. In 1230, the Sicilian School became famous for creating the first standard Italian writing style. Dante Alighieri, one of Italy's greatest poets, wrote La Divina Commedia (The Divine Comedy) around 1308–1320.

During the 14th and early 15th centuries, Renaissance humanism grew. Italian humanists wanted to teach people to speak and write clearly and beautifully. Early humanists like the poet Francesco Petrarca and the philosopher Marsilio Ficino were experts in ancient Greek and Roman writings. They also collected many old manuscripts. Lorenzo de Medici, a powerful leader from Florence, was a big supporter of the Renaissance. Leonardo da Vinci, a famous scientist and artist, wrote a book about painting. Plays also became very popular in the 15th century.

By the 16th century, Italian literature had a very clear Italian style. Niccolò Machiavelli and Francesco Guicciardini were key figures in creating the study of history. Pietro Bembo helped shape the Italian language and brought back interest in Petrarch's works.

In 1690, the Academy of Arcadia was formed. Its goal was to make literature simpler, like the ancient shepherds' poems. In the 17th century, thinkers like Giordano Bruno and Tommaso Campanella explored new ideas. They paved the way for scientific discoveries by Galileo Galilei, who was famous for both his science and his writings. In the 18th century, Italy's political situation improved. Philosophers shared their ideas across Europe during the Age of Enlightenment. Apostolo Zeno and Metastasio were important writers of this time. Carlo Goldoni, a Venetian playwright, created a new kind of comedy. Giuseppe Parini was a leading figure in the 18th-century Italian literary revival.

The ideas of the French Revolution (1789) greatly influenced Italian literature. People wanted freedom and equality. This led to writing that focused on national goals. Writers wanted to improve Italy by freeing it from political and religious control. This new literature began with the playwright Vittorio Alfieri. Other patriots included the poets Vincenzo Monti and Ugo Foscolo. The Romantic movement started with the Conciliatore magazine in Milan in 1818. The main leader of this change was Alessandro Manzoni, known for his historical novel I promessi sposi (The Betrothed, 1827–1842). The great poet of this time was Giacomo Leopardi.

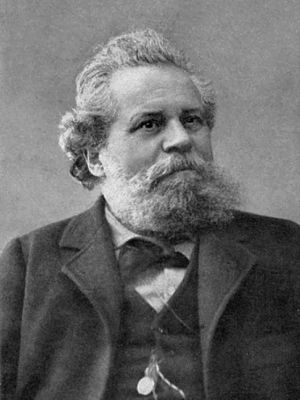

After the Risorgimento (Italian unification), political writing became less important. This period saw two new literary styles that went against Romanticism: the Scapigliatura and Verismo. Giovanni Verga, a Sicilian writer, was a key figure in Verismo. He wrote I Malavoglia (The House by the Medlar-Tree, 1881).

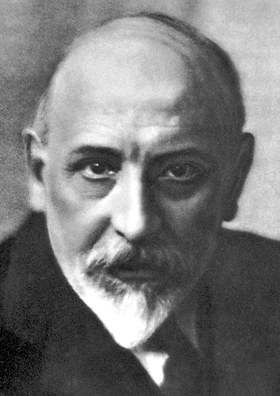

Important Italian writers of the early 20th century include Giovanni Pascoli, Italo Svevo, Gabriele D'Annunzio, Umberto Saba, Giuseppe Ungaretti, Eugenio Montale, and Luigi Pirandello (who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1934). Neorealism was developed by Alberto Moravia. Pier Paolo Pasolini became one of Italy's most talked-about authors. Umberto Eco became famous worldwide with his medieval detective story Il nome della rosa (The Name of the Rose, 1980). Six Italian authors have won the Nobel Prize in Literature: Giosuè Carducci, Grazia Deledda, Luigi Pirandello, Salvatore Quasimodo, Eugenio Montale, and Dario Fo.

Contents

- Early Medieval Latin Writing

- High Medieval Literature: New Styles Emerge

- The Rise of Italian Literature

- The 14th Century: Seeds of the Renaissance

- The 15th Century: Renaissance Humanism Flourishes

- The 16th Century: The High Renaissance

- The 17th Century: A Time of Decline

- The 18th Century: Reason and Reform

- The Revolution: Patriotism and Classicism

- 19th Century: Romanticism and Unification

- Between the 19th and 20th Century: New Directions

- 20th Century and Beyond: Modern Italian Literature

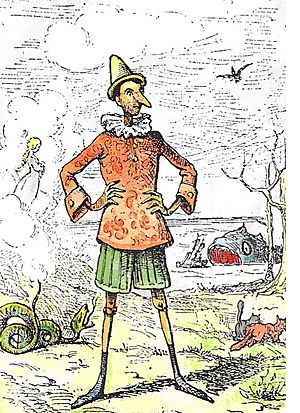

- Children's Literature: Tales for Young Readers

- Women Writers: A Growing Voice

- Italians Awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature

- See also

Early Medieval Latin Writing

As the Western Roman Empire weakened, writers like Cassiodorus and Boethius kept Latin writing alive. Learning thrived in Ravenna under Theodoric, and Gothic kings surrounded themselves with teachers of speaking and grammar. Some schools for non-religious studies remained in Italy. Important scholars included Magnus Felix Ennodius and Paulinus of Aquileia.

Italians interested in theology (the study of religion) often went to Paris. Those who stayed in Italy usually studied Roman law. This helped set up medieval universities in cities like Bologna and Padua. These universities spread knowledge and prepared the way for new writing in local Italian languages. Old traditions from ancient Rome did not disappear. Love for Rome, interest in politics, and a focus on practical matters influenced how Italian literature grew.

High Medieval Literature: New Styles Emerge

Troubadours and Early Poetry

The first local writing style in Italy used the Occitan language, spoken in parts of northwest Italy. This style of lyric poetry (poetry that expresses feelings) started in France in the early 12th century. It spread to Italy by the late 12th century. The first troubadours (called trovatori in Italian) in Italy came from other places. But rich families in Northern Italy supported them. Soon, Italians began writing poetry in Occitan themselves.

Powerful families like the House of Este and the Malaspina supported these poets. Azzo VI of Este hosted troubadours from Occitania and Rambertino Buvalelli from Bologna, one of the first Italian troubadours. These poets influenced native Italians so much that a foreign troubadour, Aimeric de Peguilhan, worried about the rise of Italian competitors in 1220.

The margraves of Montferrat also supported Occitan poetry. Raimbaut de Vaqueiras spent most of his career as a poet at the court of Boniface I. Raimbaut and other troubadours even went with Boniface on the Fourth Crusade. This briefly brought Italo-Occitan literature to Thessalonica.

Azzo VI of Este's daughter, Beatrice, was a subject of early poets' "courtly love" poems. Rambertino Buvalelli became a mayor (podestà) of Genoa in 1218. He likely brought Occitan lyric poetry to the city, which then developed its own rich Occitan literary scene.

Genoese troubadours included Lanfranc Cigala, a judge, and Calega Panzan, a merchant. Genoa also saw the rise of "podestà-troubadours." These were men who served as mayors in different cities and wrote political poetry in Occitan. Rambertino Buvalelli was the first of these.

The Occitan tradition in Italy was widespread. Bertolome Zorzi was from Venice. Nicoletto da Torino was likely from Turin. Terramagnino da Pisa wrote a guide to courtly love. He wrote in both Occitan and Italian. Paolo Lanfranchi da Pistoia also wrote in both languages.

Perhaps the most important Italian troubadour was Sordello (1220s–1230s), from Goito near Mantua.

Troubadours were also connected to a new poetry style in the Kingdom of Sicily. In 1220, Obs de Biguli was a "singer" at the crowning of Emperor Frederick II. Guillem Augier Novella and Guilhem Figueira were important Occitan poets at Frederick's court. They had fled the Albigensian Crusade, which had destroyed their home region. This crusade also led many troubadours to Italy, where they began an Italian tradition of criticizing the Pope. Protected by the emperor, criticism of the Church grew.

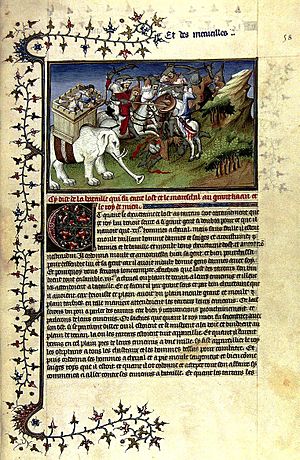

Chivalric Romances: Tales of Heroes

The Historia de excidio Trojae claimed to be an eyewitness account of the Trojan War. It inspired writers in other countries. Guido delle Colonne of Messina, a poet from the Sicilian school, wrote Historia destructionis Troiae. He turned a French romance into what sounded like a serious Latin history.

Similar things happened with other famous legends. Quilichino of Spoleto wrote about Alexander the Great. Europe was full of King Arthur stories, but Italians mostly translated and shortened French romances. Jacobus de Voragine collected his Golden Legend (1260), focusing on history. Italian thinkers were very practical, especially in studying Roman law. This helped spread culture and prepared the way for new Italian literature.

At the same time, epic poems were written in a mix of Italian and French. This language had French roots but Italian endings. Examples include chansons de geste like Macaire and the Entrée d'Espagne. All this happened before purely Italian literature appeared.

The Rise of Italian Literature

The French and Occitan languages slowly gave way to native Italian. Mixed languages still appeared, but they were no longer dominant. In works like Bovo d'Antona, the Venetian influence is clear, though French forms are still present. These "mixed" writings came just before truly Italian works.

Some early Italian literature existed before the 13th century. Works like the Ritmo cassinese and Laudes creaturarum are called "Archaic Works." They date from the late 12th to early 13th centuries. However, these early writings did not have a uniform style or language.

This early development happened across Italy, but the topics varied. In the north, poems by Giacomino da Verona were mostly religious. They were meant to be recited to people. These were written in Lombard and Venetian dialects. They were a type of "popular" poetry. This style might have been encouraged by the old custom of listening to singers in town squares. Crowds enjoyed stories of romances and religious poems.

The Sicilian School: A New Standard

The year 1230 marked the start of the Sicilian School. This style of literature showed more consistent features. Its main importance was creating the first standard Italian language. Its subject was often love songs, partly based on Provençal poetry brought to the south by the Normans. This poetry treated women in a more platonic way, focusing on spiritual love. This idea was later developed by the Dolce Stil Novo in Bologna and Florence. Words from chivalry were adapted to Italian, creating new vocabulary. French endings like -ière and -ce led to hundreds of new Italian words like -iera and -za. Dante and his friends used these words, passing them on to future writers.

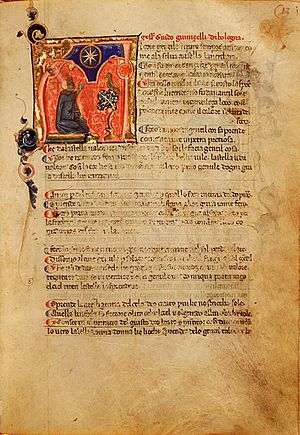

The Sicilian school included poets like Enzio of Sardinia, Pietro della Vigna, and Giacomo da Lentini. Giacomo da Lentini, the leader, is famous for Io m'aggio posto in core (I have stated within my heart). Even Frederick II himself wrote poetry. Giacomo da Lentini is also credited with inventing the sonnet, a poem form later perfected by Dante and Petrarch. Frederick's strict rule meant that political topics were not allowed in literature. In contrast, northern Italian poetry, from cities with more democratic governments, explored new political ideas. This is seen in the Sirventese style and later in Dante's Commedia, which criticized political leaders and popes.

While formal love songs were common at Frederick's court, more spontaneous poetry also existed. The Contrasto by Cielo d'Alcamo is an example. This "dispute" between two lovers in the Sicilian language shows that popular, independent poetry existed. It was probably a scholarly version of a lost popular rhyme. It was very different from the formal Sicilian School poetry, with strong feelings and sometimes bold ideas.

The poems of the Sicilian school were written in the first known standard Italian. This language was created by these poets under Frederick II. It combined features of Sicilian and Apulian dialects with words from Latin and French. Dante studied the Sicilian School's language. When Tuscan writers copied these poems, they sometimes changed the vowel sounds. This led to "Sicilian rhyme," where lines might not perfectly rhyme to a Tuscan ear. Dante and Petrarch later used this as a display of skill.

Religious Writings: Faith and Satire

In the 13th century, a religious movement grew in Italy with the rise of the Dominican and Franciscan Orders. The earliest Italian sermons we have are from Jordan of Pisa, a Dominican. Francis of Assisi, a mystic and founder of the Franciscans, also wrote poetry. Francis's poetry was simpler than the refined court poetry. Legend says Francis wrote the hymn Cantico del Sole in his later years. It was the first major poem from Northern Italy, using a style of rhyming called assonance.

Jacopone da Todi was a poet who showed the strong religious feeling in Umbria. Jacopone was a mystic like St. Francis. But he was also a satirist who made fun of the corruption and hypocrisy of the Church, especially Pope Boniface VIII. After his wife died, Jacopone gave away all his possessions to the poor. He joined St. Francis's Third Order and lived a very strict life. He was a mystic who criticized popes, even being imprisoned for it.

The religious movement in Umbria also led to religious plays. In 1258, a hermit named Raniero Fasani appeared in Perugia. He claimed God sent him to warn people of terrible events. This was a time of political fighting and Church punishments. Fasani's warnings led to the formation of the Compagnie di Disciplinanti. These groups would whip themselves as penance and sing Laudi (praise songs) in dialogue. These laudi, connected to church services, were the first plays in Italian. They were written in the Umbrian dialect and were simple, but they developed quickly. By the late 13th century, plays mixing church services and drama appeared.

First Tuscan Literature: Humor and Philosophy

The 13th century in Tuscany was special. The Tuscan dialect was very similar to Latin. It later became the main language of Italian literature. By the end of the 13th century, people already thought it was better than other dialects. After the fall of the Hohenstaufen family in 1266, Tuscany became the leading region in Italy. From 1266, Florence started political reforms. This led to the appointment of the Priori delle Arti (leaders of the guilds) in 1282. This system was copied by other cities like Siena and Lucca. The guilds took control of the government, leading to a time of social and political success.

In Tuscany, popular love poetry also existed. A group of poets copied the Sicilians, led by Dante da Majano. But Tuscan writing also developed a unique style of humorous and satirical poetry. The democratic government led to poetry that went against the old mystical and chivalrous styles. Serious poems about God or ladies came from monasteries and castles. But in the cities, everything was treated with ridicule or sharp sarcasm. Folgore da San Gimignano wrote funny sonnets about what Sienese youths did each month. Cenne della Chitarra parodied Folgore's sonnets. The sonnets of Rustico di Filippo and Cecco Angiolieri were half-funny, half-satirical. Cecco Angiolieri is considered the oldest humorist we know.

Another kind of poetry also started in Tuscany. Guittone d'Arezzo moved art away from chivalry and Provençal styles. He tried political poetry. Though his work is often hard to understand, he prepared the way for the Bolognese school. Bologna was a city of science, and philosophical poetry appeared there. Guido Guinizelli was a poet of this new style. In his work, ideas of chivalry changed. He believed that only those with a pure heart could experience true love, no matter their social class. He argued against the old idea that love was only for a few chosen knights and princesses. Love, he said, is blind to titles but not to a good heart. It comes from a spiritual connection between two souls. Guinizelli's democratic view makes sense given the greater equality in central and northern Italian city-states. His poem "Al cor gentil" ("To a Kind Heart") is seen as the main statement of the Dolce Stil Novo movement. This movement flourished in Florence with poets like Guido Cavalcanti and Dante.

In the 13th century, there were several important allegorical poems. One was by Brunetto Latini, a close friend of Dante. His Tesoretto is a short poem where the author gets lost and meets a lady representing Nature. She teaches him many things. This poem shows vision, allegory, and moral teaching, all elements found in the Divine Comedy. Francesco da Barberino wrote two small allegorical poems, Documenti d'amore and Del reggimento e dei costumi delle donne. These are now studied more for historical context than as literature. The Intelligenza was another allegorical work, possibly a translation of French poems.

In the 15th century, the publisher Aldus Manutius published works by Tuscan poets Petrarch and Dante Alighieri (The Divine Comedy). This helped create a standard for modern Italian.

Early Italian Prose: Stories and Histories

Italian prose (writing that is not poetry) in the 13th century was rich and varied. The earliest example is from 1231, short notes about money by Mattasala di Spinello dei Lambertini of Siena. At this time, there was no clear literary prose in Italian, though there was in French. Around the middle of the century, Aldobrando, from Florence or Siena, wrote Le Régime du corps for Beatrice of Savoy. In 1267, Martino da Canale wrote a history of Venice in Old French. Rustichello da Pisa, who spent time at the court of Edward I of England, wrote many chivalrous romances. He also wrote the Travels of Marco Polo, which Marco Polo himself might have told him. Finally, Brunetto Latini wrote his Tesoro in French. Latini also wrote some Italian prose works, like La rettorica, based on Cicero's De inventione.

Another important writer was Bono Giamboni from Florence. He translated several Latin works and wrote an allegorical novel called Libro de' Vizi e delle Virtudi. Andrea of Grosseto translated three Latin works into the Tuscan dialect in 1268.

After original works in French, came translations and adaptations. There were moral stories from religious legends, a romance about Julius Caesar, and short histories of ancient knights. Translations of Marco Polo's Viaggi and Latini's Tesoro also appeared. Latin moral, historical, and rhetorical works were also translated. Composizione del mondo, a science book by Ristoro d'Arezzo (mid-13th century), is also notable. It's a detailed book on astronomy and geography. Ristoro was a careful observer, and his work is more reliable than others of his time.

Another short book is De regimine rectoris by Paolino Veneto, a friar from Venice. He was a bishop and also wrote a Latin chronicle. His book is similar to Egidio Colonna's De regimine principum and is written in Venetian.

The 13th century was rich in tales. The Cento Novelle antiche collection has stories from many sources: Asian, Greek, Trojan, ancient and medieval history, legends from Brittany, Provence, and Italy, the Bible, and animal stories. This book is similar to the Spanish El Conde Lucanor. The Italian stories are very short, like outlines for a storyteller to fill in. Other prose stories were included by Francesco da Barberino in his Del reggimento e dei costumi delle donne, but they are less important.

Overall, Italian novels of the 13th century were not very original. They were faint copies of the rich French legendary literature. The Lettere of Guittone d'Arezzo are worth noting. He wrote many poems and some prose letters on moral and religious topics. Guittone loved ancient Rome and its language so much that he tried to write Italian in a Latin style. His letters are often unclear and difficult. Guittone saw his style as very artistic, but later scholars found it exaggerated.

Dolce Stil Novo: Sweet New Style

With poets like Lapo Gianni, Guido Cavalcanti, Cino da Pistoia, and Dante Alighieri, lyric poetry became purely Tuscan. Dante said the new style's power came from expressing soul feelings as love inspires them, in a beautiful and fitting way. Love is a divine gift that helps people connect with God. The poet's beloved is an angel sent from heaven to show the path to salvation. This is a neo-Platonic idea, strongly supported by Dolce Stil Novo. Even if it can be difficult, it's a spiritual experience that lifts people to a higher level. Gianni's new style was still influenced by the Siculo-Provençal school.

Cavalcanti's poems are of two types: those that show him as a philosopher and those that are more poetic, filled with mysticism and metaphysics. His famous poem Sulla natura d'amore is a philosophical work on love. In other poems, Cavalcanti sometimes buried poetic images under too much philosophy. However, in his Ballate, he expressed himself simply but with great art. His best ballata was written when he was exiled from Florence in 1300.

The third important poet of this new school was Cino da Pistoia. His love poems are sweet, gentle, and musical.

The 14th Century: Seeds of the Renaissance

Dante Alighieri: The Divine Poet

Dante Alighieri, one of Italy's greatest poets, also showed these lyrical qualities. In 1293, he wrote La Vita Nuova ("new life"). He called it "new life" because his first meeting with Beatrice began a new phase in his life. In this work, he idealizes love. It's a collection of poems with Dante's own explanations and stories. Everything is spiritual and heavenly. The real Beatrice becomes an idealized vision, a symbol of the divine. Dante is the main character, and the story seems autobiographical, though it's a poetic interpretation of his life.

Many poems in La Vita Nuova are about this new life. Not all love poems are about Beatrice; some are philosophical and connect to his later work, Convivio.

The Divine Comedy: A Journey Through the Afterlife

La Divina Commedia tells the story of the poet's journey through the three parts of the afterlife: Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise. He is guided by the Roman poet Virgil. This great epic has a hidden allegorical meaning. Dante's journey symbolizes humanity trying to achieve both earthly and eternal happiness. The forest where he gets lost represents sin. The mountain lit by the sun represents a universal monarchy.

The three beasts are three vices and three powers that stood in Dante's way. Envy is Florence, divided by political factions. Pride is the French royal family. Greed is the Pope's court. Virgil represents reason and the empire. Beatrice symbolizes the divine help humanity needs to reach God.

The poem's greatness is not just in its allegory, which links it to medieval literature. What is new is Dante's unique artistic skill. He was the first to combine classic art with a Romance language form. Whether he describes nature, explores emotions, curses vices, or praises virtues, Dante is remarkable for his grand and delicate art. He used ideas from theology, philosophy, history, and mythology. But he especially drew from his own feelings of hatred and love. Through his writing, the dead come alive again. They become real people and speak the language of their time and passions. Characters like Farinata degli Uberti and Count Ugolino are vivid creations. They appear before us with all their unique traits and feelings.

Dante himself is the one who punishes sins and rewards virtues. His personal involvement in describing these three worlds is what truly interests and moves us. Dante reshapes history based on his own feelings. So, the Divina Commedia is not just a lively drama of contemporary thoughts. It's also a clear reflection of the poet's own feelings. These range from the anger of a citizen and exile to the faith of a believer and the passion of a philosopher. The Divina Commedia is considered one of the finest works in world literature.

Petrarch: The First Modern Lyric Poet

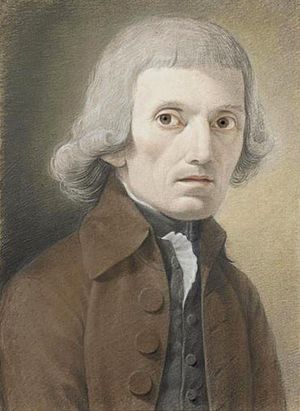

Two things define Petrarch's literary life: his study of classical works and the new human emotion in his lyric poetry. Petrarch, who found works by great Latin writers, also loved a real woman named Laura. He wrote poems about her during her life and after her death, full of elegant style. Petrarch was the first humanist and the first modern lyric poet. His career was long and eventful. He lived for many years in Avignon, criticizing the corrupt papal court. He traveled across Europe and corresponded with emperors and popes. He was considered the most important writer of his time.

His Canzoniere is divided into three parts: poems written during Laura's life, poems written after her death, and the Trionfi. The only subject of these poems is love. But the way he treats it is very varied in ideas, images, and feelings. Petrarch's lyric poetry is different from that of the Provençal troubadours, earlier Italian poets, and even Dante. Petrarch is a psychological poet. He examines all his feelings and expresses them with exquisite sweetness. His lyrics are not spiritual like Dante's, but stay within human limits. The second part of the Canzoniere is more passionate. The Trionfi are not as good; in them, Petrarch tried to copy the Divina Commedia but didn't succeed. The Canzoniere also includes a few political poems. Some are addressed to Cola di Rienzi and others criticize the court of Avignon. These poems are powerful and show that Petrarch had a broader sense of Italian identity than Dante. He imagined an Italy different from what people in the Middle Ages thought. In this way, he was a pioneer of modern times. Petrarch didn't have a fixed political idea. He praised Cola di Rienzi, called on Emperor Charles IV, and admired the Visconti. His politics were more influenced by feelings than by principles. Above all, he loved Italy, which he linked to Rome, the great city of his heroes, Cicero and Scipio. Some say Petrarch started Renaissance humanism.

Boccaccio: Master of Prose

Giovanni Boccaccio shared Petrarch's love for ancient writings and new Italian literature. He was the first to translate the Iliad into Latin and, in 1375, the Odyssey. His knowledge of classical works is shown in De genealogia deorum. In this book, he lists gods from different authors who wrote about pagan deities. The Genealogia deorum is like an encyclopedia of mythology. It was a precursor to the humanist movement of the 15th century. Boccaccio was also the first historian of women in his De mulieribus claris. He was also the first to tell the stories of famous unlucky men in his De casibus virorum illustrium. He continued geographical studies in his book De montibus, silvis, fontibus, lacubus, fluminibus, stagnis, et paludibus, et de nominibus maris.

Of his Italian works, his lyrics are not as perfect as Petrarch's. His narrative poetry is better. He didn't invent the octave stanza, but he was the first to use it in a long, artistic work, his Teseide. This is the oldest Italian romantic poem. The Filostrato tells the love story of Troiolo and Griseida (Troilus and Cressida). Boccaccio might have known the French poem about the Trojan War. But his poem's interest lies in how it explores the feeling of love. The Ninfale fiesolano tells the love story of the nymph Mesola and the shepherd Africo. The Amorosa Visione, a poem in triplets, was likely inspired by the Divina Commedia. The Ameto mixes prose and poetry and is the first Italian pastoral romance.

The Filocopo is the earliest of his prose romances. It has a lot of mythology, which harms it as an artwork but helps us understand Boccaccio's mind. The Fiammetta is another romance, about Boccaccio's love for Maria d'Aquino, whom he called Fiammetta.

Boccaccio became famous mainly for his Italian work, Decamerone. This is a collection of one hundred stories. They are told by a group of men and women who went to a villa near Florence to escape the plague in 1348. Storytelling, common in earlier centuries, especially in France, now became an art form for the first time. Boccaccio's style tries to imitate Latin. But with him, prose first became a refined art. The roughness of old fabliaux (short, humorous tales) was replaced by careful work from a mind that appreciated beauty. He studied classical authors and tried to copy them. In the Decamerone, Boccaccio also describes characters and observes emotions. This was his new contribution. Many sources for the Decamerone have been discussed. Boccaccio probably used both written and oral sources. Popular traditions likely gave him material for many stories, like that of Griselda.

Unlike Petrarch, who was often unhappy and worried, Boccaccio was calm and content. Despite these differences, the two great authors were old and close friends. But their feelings for Dante were not the same. Petrarch, who said he saw Dante once as a child, didn't remember him fondly. It's clear he was jealous of Dante's fame. Boccaccio sent him the Divina Commedia when Petrarch was old, and Petrarch admitted he never read it. Boccaccio, however, felt great enthusiasm for Dante. He wrote a biography of him and gave public lectures on the poem in Florence.

Other Writers of the 14th Century

Imitators and Storytellers

Fazio degli Uberti and Federico Frezzi copied the Divina Commedia, but only its outer form. Fazio wrote Dittamondo, a long poem where he travels the world with a geographer. Frezzi, a bishop, wrote Quadriregio, a poem about the four kingdoms of Love, Satan, Vices, and Virtues. This poem is similar to the Divina Commedia. Frezzi shows a person moving from vice to virtue, describing hell, purgatory, and heaven.

Ser Giovanni Fiorentino wrote a collection of tales called Pecorone. These stories were supposedly told by a monk and a nun. He copied Boccaccio closely and used Villani's chronicle for historical stories. Franco Sacchetti also wrote tales, mostly about Florentine history. His book gives a lively picture of Florentine society in the late 14th century. The stories are often improper, but Sacchetti used them to draw his own moral lessons. Giovanni Sercambi of Lucca wrote a book in 1374, imitating Boccaccio. It was about people escaping a plague and traveling through Italian cities, telling stories. Later important writers include Masuccio Salernitano (Tommaso Guardato), who wrote Novellino, and Antonio Cornazzano whose Proverbii became very popular.

Chronicles: Recording History

Many chronicles once thought to be from the 13th century are now believed to be fakes. At the end of the 13th century, there is a chronicle by Dino Compagni, which is likely real.

Giovanni Villani, born in 1300, was more of a chronicler than a historian. He wrote about events up to 1347. His travels in Italy and France gave him information, so his chronicle, Historie Fiorentine, covers events across Europe. He wrote in detail not only about politics and war, but also about public officials' salaries, money spent on soldiers and festivals, and other valuable facts. Villani's story often includes fables and errors, especially when he talks about things that happened before his time.

Matteo, Giovanni Villani's brother, continued the chronicle up to 1363. It was then continued by Filippo Villani.

Religious Writers: Faith and Reform

The Divine Commedia has religious themes. Petrarch's work also has similar qualities. But neither Petrarch nor Dante were pure religious writers of their time. Many other writers, however, fit this description. St Catherine of Siena's religious ideas were also political. This amazing woman wanted to bring the Church of Rome back to its original virtues. She left a collection of letters written in a powerful tone to various people, including popes. Her voice was the clearest religious message in 14th-century Italy. She didn't have specific reform ideas, but she deeply felt the need for a great moral change. She helped prepare the way for the religious movement of the 16th century.

Another Sienese, Giovanni Colombini, founded the order of Jesuati. He taught poverty by example, going back to St Francis of Assisi's religious ideas. His letters are among the most notable religious works of the 14th century. Bianco da Siena wrote several popular religious poems (lauda). Jacopo Passavanti, in his Specchio della vera penitenza, combined teaching with stories. Domenico Cavalca translated Vite de' Santi Padri from Latin. Rivalta left many sermons, and Franco Sacchetti (the famous novelist) wrote many speeches. Overall, religious literature was one of the most important types of writing in 14th-century Italy.

Popular and Political Works

Humorous poetry, which grew in the 13th century, continued in the 14th century with writers like Bindo Bonichi and Antonio Pucci. Pucci was better than the others because of his varied works. He put Giovanni Villani's chronicle into triplets (Centiloquio). He also wrote many historical poems called Serventesi, many comic poems, and epic-popular works on different topics. One of his short poems in seven cantos is about the war between Florence and Pisa from 1362 to 1365.

Other poems based on legends celebrate the Reina d'Oriente, Apollonio di Tiro, and the Bel Gherardino. These poems, meant to be recited, are the ancestors of the romantic epic.

Many poets of the 14th century wrote political works. Fazio degli Uberti, who wrote Dittamondo, also wrote a Serventese to the lords and people of Italy. He wrote a poem about Rome and a strong criticism against Charles IV. Other notable political poets include Francesco di Vannozzo and Matteo Frescobaldi. Generally, following Petrarch's example, many writers focused on patriotic poetry.

From this period also came "Petrarchism." These were poets who wrote about love, copying Petrarch's style. They appeared in the 14th century. But others wrote about love more originally, in a style that could be called semi-popular. Examples include the Ballate of Ser Giovanni Fiorentino and Franco Sacchetti. Ballate were poems sung for dancing, and many songs for music exist from the 14th century. Antonio Pucci put Villani's Chronicle into verse. There is also a chronicle of Arezzo in terza rima by Bartolomeo Sinigardi. And the history of Pope Alexander III's journey to Venice, also in terza rima, by Pier de Natali. Besides this, all kinds of subjects, like history, tragedy, or farming, were put into verse. Neri di Landocio wrote a life of St Catherine. Jacopo Gradenigo put the Gospels into triplets.

The 15th Century: Renaissance Humanism Flourishes

Renaissance humanism grew during the 14th and early 15th centuries. It was a response to medieval education, which focused on preparing doctors, lawyers, or theologians. Humanism emphasized practical studies. The main centers of humanism were Florence and Naples.

Instead of training professionals in specific fields, humanists wanted to create citizens who could speak and write clearly and eloquently. This would help them participate better in their communities and encourage good actions. This was done by studying the studia humanitatis, now known as the humanities: grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, and moral philosophy.

Early humanists like Petrarch and Coluccio Salutati collected many old manuscripts. Many worked for the Church, while others were lawyers and city officials. They had access to workshops that copied books.

In Italy, the humanist education quickly became popular. By the mid-15th century, many upper-class people had received humanist training. Some high Church officials were humanists who built important libraries. Cardinal Basilios Bessarion, a very learned scholar, was one such example. There were five humanist Popes in the 15th century. One of them, Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini (Pius II), wrote many books, including one on "The Education of Boys."

Literature in Florence: The Medici Influence

Leone Battista Alberti, a scholar of Greek and Latin, wrote in Italian. Vespasiano da Bisticci, though busy with Greek and Latin manuscripts, wrote Vite di uomini illustri. This work is valuable for its historical content and its simple style, similar to the best works of the 14th century. Andrea da Barberino wrote the beautiful prose of the Reali di Francia, giving a Roman feel to chivalrous romances. Belcari and Girolamo Benivieni returned to the mystical ideas of earlier times.

But the influence of Florence on the Renaissance is most clearly seen in Cosimo de' Medici and Lorenzo de Medici, from 1430 to 1492. Lorenzo de Medici's mind was shaped by ancient writers. He attended Greek classes, participated in Platonic discussions, and collected old books, sculptures, and paintings. He used these to decorate his gardens and create the Laurentian Library. In his Florentine palace and villas, he had amazing art. De Medici lived entirely in the classical world. Yet, his poems show him as a man of his time, admiring Dante and old Tuscan poets. He was inspired by popular music and wrote poetry with both strong realism and high idealism. He could switch from a Platonic sonnet to passionate triplets, from grand songs to simple ones. He had a strong feeling for nature. His writing was sometimes sweet and sad, sometimes strong and deep, reflecting his busy life. He liked to examine his own heart closely. He described things like a sculptor, satirized, laughed, prayed, and sighed. He was always elegant, always a Florentine, but a Florentine who read ancient Greek and Roman poets. He wanted to enjoy life and also appreciate refined art.

Next to Lorenzo was Poliziano. He also combined ancient and modern, popular and classical styles, with even greater skill. In his Rispetti and Ballate, his fresh images and clear forms are unique. Poliziano, a great Greek scholar, wrote Italian verses with brilliant colors. The pure elegance of Greek sources filled his art in all its forms, from Orfeo to Stanze per la giostra.

A completely new type of poetry emerged: the Canto carnascialesco. These were choral songs, performed with symbolic masked parades during carnival in Florence. They were written in a meter similar to ballate. Most were sung by groups of workers and tradesmen, who praised their crafts with not-so-clean jokes. Lorenzo himself organized these parades. In the evenings, large groups on horseback would go through the city, playing and singing these songs. Some by Lorenzo himself are the best. The one called Bacco ed Arianna is the most famous.

Epic Poems: Pulci and Boiardo

Italy did not yet have true epic poetry. But it had many poems called cantari, which were stories sung to the people. There were also romantic poems like Buovo d'Antona. But the first to bring life to this style was Luigi Pulci. He grew up in the Medici household and wrote the Morgante Maggiore at the request of Lucrezia Tornabuoni, Lorenzo de' Medici's mother. The story of Morgante comes almost entirely from an old chivalrous poem. Pulci created his own work, often making fun of the subject, exaggerating characters, and adding many side stories. He turned the romantic epic into an artwork, mixing serious and funny parts.

With a more serious goal, Matteo Boiardo, Count of Scandiano, wrote his Orlando innamorato. He tried to include all the Carolingian legends, but he didn't finish it. This work also has a lot of humor. Still, Boiardo was drawn to the world of romance by a deep love for chivalrous manners and feelings: love, courtesy, bravery, and generosity. A third romantic poem of the 15th century was Mambriano by Francesco Bello. He used stories from the Carolingian cycle, the Round Table romances, and classical antiquity. He was a talented poet with a vivid imagination. He showed the influence of Boiardo.

Other Notable Figures

History was not widely studied or well-written in the 15th century. Its revival came in the next age. Most history was written in Latin. Gioviano Pontano wrote the history of Naples, and Leonardo Bruni of Arezzo wrote the history of Florence, both in Latin. Bernardino Corio wrote the history of Milan in Italian.

Leonardo da Vinci wrote a book on painting. Leone Battista Alberti wrote on sculpture and architecture. But these two men are important not just for their books. They represent another key feature of the Renaissance: their amazing versatility. They could do many different things and be excellent at all of them. Leonardo was an architect, poet, painter, engineer, and mathematician. Alberti was a musician, studied law, was an architect and artist, and was famous in literature. He had a deep feeling for nature and a unique ability to understand everything he saw and heard. Leonardo and Alberti are examples of the great intellectual energy of the Renaissance.

Piero Capponi, who wrote Commentari deli acquisto di Pisa, lived in both the 14th and 15th centuries. Albertino Mussato of Padua wrote a Latin history of Emperor Henry VII. He then wrote a Latin tragedy about Ezzelino da Romano, called Eccerinus. This was a unique work.

The development of drama in the 15th century was very significant. This type of popular literature started in Florence. It was linked to popular festivals, usually held for St John the Baptist, the city's patron saint. The Sacra Rappresentazione (Sacred Representation) grew from the medieval Mistero (mystery play). Although it was popular poetry, some famous writers created them. Lorenzo de Medici, for example, wrote San Giovanni e Paolo. Belcari wrote San Panunzio and Abramo ed Isaac. From the 15th century, some funny, non-religious elements found their way into the Sacra Rappresentazione. Poliziano broke away from its traditional style in his Orfeo. While its outer form was like sacred plays, its content and artistic elements were different.

The 16th Century: The High Renaissance

The main feature of literature after the Renaissance was its perfection in all art forms. It combined the Italian character of its language with classical style. This period lasted from about 1494 to 1560. 1494 was when Charles VIII came to Italy, marking the start of foreign rule and political decline.

Famous writers of the early 16th century were educated in the previous century. Pietro Pomponazzi was born in 1462, Niccolò Machiavelli in 1469, Pietro Bembo in 1470, Michelangelo Buonarroti and Ariosto in 1474, and Francesco Guicciardini in 1483. The literary activity from the late 15th to mid-16th century was a result of earlier political and social conditions.

Baldassare Castiglione: The Ideal Courtier

Baldassare Castiglione wrote Il Cortegiano or The Book of the Courtier. This book discusses the manners and morals of a courtier (a person who attends a royal court). Published in 1528, it was very influential in European courts during the 16th century. The Book of the Courtier is a long philosophical discussion. It explores what makes an ideal courtier or court lady, someone worthy to advise a prince or leader. Castiglione set the book's story during his time as a courtier in his home region, the Duchy of Urbino. The book quickly became very popular. Readers saw it as a guide to etiquette and manners, especially for royal courts. Other such books included Giovanni Della Casa's Galateo (1558). However, The Book of the Courtier was more than just a manners guide. It was like a play, an open philosophical debate, and an essay. Some also saw it as a hidden political allegory.

History as a Science: Machiavelli and Guicciardini

Niccolò Machiavelli and Francesco Guicciardini were the main founders of the science of history. Machiavelli's most important works are Istorie fiorentine, Discorsi sulla prima deca di Tito Livio, Arte della guerra, and Principe. His contribution was emphasizing the experimental side of politics. He observed facts, studied histories, and drew principles from them. His history is sometimes factually incorrect. It is more a political work than a historical one. Machiavelli's genius, as has been said, lay in his artistic ability to treat politics for its own sake. He could step back from temporary events to understand the lasting nature of power.

Next to Machiavelli, both as a historian and a statesman, comes Guicciardini. Guicciardini was very observant. He tried to turn his observations into a science. His Storia d'Italia, which covers the period from Lorenzo de Medici's death to 1534, is full of political wisdom. It is well-organized, vividly describes the characters, and is written in a grand style. He showed a deep understanding of the human heart. He accurately portrayed the temperaments and habits of different European nations. He looked for the causes of events, explaining the different interests of princes and their rivalries. The fact that he witnessed and participated in many of the events he wrote about adds authority to his words. His political thoughts are always deep. In his Pensieri, he tried to extract the essence of what he observed and did. He aimed to create a political theory that was as complete as possible. Machiavelli and Guicciardini are considered distinguished historians and founders of history based on observation.

Less important, but still notable, were Jacopo Nardi (a fair and loyal historian who defended Florence against the Medici), Benedetto Varchi, Giambattista Adriani, Bernardo Segni, and, outside Tuscany, Camillo Porzio. Porzio wrote about the Congiura de baroni and Italian history from 1547 to 1552. Also, Angelo di Costanzo, Pietro Bembo, Paolo Paruta, and others.

Ludovico Ariosto: The Romantic Epic

Ludovico Ariosto's Orlando furioso continued Boiardo's Innamorato. His unique quality was that he blended the chivalrous romance with classical style. Ariosto was an artist who loved art for its own sake. His epic poem had no serious purpose. Instead, it created a fantasy world where the poet wandered, indulged his whims, and sometimes even smiled at his own work. His main goal was to describe everything as perfectly as possible. He focused most on refining his style. In his hands, the style became wonderfully flexible for any idea, whether grand or simple, serious or playful. With him, the octave stanza reached a high level of grace, variety, and harmony.

Pietro Bembo: Shaping the Italian Language

Pietro Bembo was a key figure in developing the Italian language, specifically Tuscan, for literary use. His writings helped revive interest in Petrarch's works in the 16th century. As a writer, Bembo tried to bring back some of the legendary "affect" that ancient Greek had on its listeners, but in Tuscan Italian. He saw Petrarch and Boccaccio as perfect models and the highest examples of poetic expression in Italian. He helped bring their 14th-century works back into fashion.

In his Prose della volgar lingua, he presented Petrarch as the ideal model. He discussed verse composition in detail, including rhyme, stress, word sounds, balance, and variety. Bembo believed that the specific arrangement of words in a poem, paying close attention to their consonants and vowels, rhythm, and position within lines, could create emotions ranging from sweetness to grief in a listener. This work was very important for the development of the Italian madrigal, the most famous secular musical form of the 16th century. Poems carefully built (or analyzed) according to Bembo's ideas were the main texts for this music.

Torquato Tasso: The Heroic Poet

Historians of Italian literature debate whether Torquato Tasso belongs to the peak of the Renaissance or forms his own period. He was certainly very different from his century. His strong religious faith, serious character, deep sadness, and constant desire for perfection set him apart from writers like Machiavelli and Ariosto. As Carducci said, Tasso is Dante's true heir. He believes and uses philosophy to explain his faith. He loves and comments on his love in a learned way. He is an artist and writes philosophical dialogues. He was only eighteen in 1562 when he tried epic poetry, writing Rinaldo. He said he tried to combine Aristotle's rules with Ariosto's variety. He later wrote Aminta, a beautiful pastoral play. But his main work was an heroic poem that took all his effort. He explained his goals in three Discorsi, written while he composed the Gerusalemme. He wanted a great and wonderful subject, not too old to lose interest, nor too new to prevent poetic additions. He would follow the rules of unity of action from Greek and Latin poems, but with more variety and splendor of episodes, so it would not be less grand than a romantic poem. Finally, he would write it in a grand and ornate style.

This is what Tasso did in the Gerusalemme liberata. Its subject is the liberation of Jesus Christ's sepulchre in the 11th century by Godfrey of Bouillon. The poet doesn't follow all historical facts exactly. He shows the main causes of events, bringing in the supernatural actions of God and Satan. The Gerusalemme is the best heroic poem Italy has. It comes close to classical perfection. Its episodes are especially beautiful. It has deep feeling, and everything reflects the poet's sad soul. However, regarding style, Tasso tried hard to stick to classical models. But he used too many metaphors, antithesises, and far-fetched ideas. Because of this, some historians place Tasso in the literary period known as Secentismo. Others, more moderately, say he prepared the way for it.

Other Writers of the 16th Century

There was also an attempt at the historical epic. Gian Giorgio Trissino of Vicenza wrote a poem called Italia liberata dai Goti. Full of learning and ancient rules, he based his work on classical authors to sing about the campaigns of Belisarius. He said he forced himself to follow all of Aristotle's rules and imitated Homer. This was another product of the Renaissance. Although Trissino's work lacks original ideas and poetic color, it helps us understand the mindset of the 16th century.

Lyric poetry did not reach great heights in the 16th century. Originality was missing, as it seemed nothing better could be done than to copy Petrarch. Still, there were some strong poets. Monsignore Giovanni Guidiccioni of Lucca (1500–1541) showed a generous heart. In beautiful sonnets, he expressed his sorrow for his country's sad state. Francesco Molza of Modena (1489–1544), learned in Greek, Latin, and Hebrew, wrote gracefully and with spirit. Giovanni della Casa (1503–1556) and Pietro Bembo (1470–1547), though Petrarchists, were elegant. Even Michelangelo was sometimes a Petrarchist, but his poems show his unique genius. Many ladies were also poets, like Vittoria Colonna (loved by Michelangelo), Veronica Gambara, and Tullia d'Aragona. They were very delicate poets, and more talented than many male writers of their time. Isabella di Morra is a unique example of female poetry from this period. Her sad life is one of the most touching and tragic stories from the Italian Renaissance.

Many tragedies were written in the 16th century, but they were all weak. This was due to the Italians' moral and religious indifference, and a lack of strong emotions and characters. The first to write for the tragic stage was Trissino with his Sofonisba. He followed art rules strictly, but the verses were weak and lacked feeling. The Oreste and Rosmunda by Giovanni di Bernardo Rucellai were no better, nor was Luigi Alamanni's translation of Antigone. Sperone Speroni in his Canace and Giraldi Cintio in his Orbecche tried to innovate in tragedy. But they were criticized for being grotesque and for debates about proper style. They were often seen as inferior to Torquato Tasso's Torrismondo, especially for its choruses, which sometimes recall Greek tragedies.

Italian comedy in the 16th century was almost entirely based on Latin comedy. Plots and characters (old man, servant, maid) were often similar. For example, Lucidi by Agnolo Firenzuola and Vecchio amoroso by Donato Giannotti were modeled on comedies by Plautus. Only three writers stand out among the many who wrote comedies: Machiavelli, Ariosto, and Giovanni Maria Cecchi. In his Mandragola, Machiavelli created a comedy of character. His personalities seem alive even now because he copied them from real life with a keen eye. Ariosto, on the other hand, was known for his portrayal of his time's customs, especially those of the Ferrarese nobles, rather than for objective character descriptions. Lastly, Cecchi's comedies are a treasure of spoken language. They wonderfully allow us to understand that age. The famous Pietro Aretino might also be included among the best comedy writers.

The 15th century included humorous poetry. Antonio Cammelli is notable for his sharp humor. But it was Francesco Berni who perfected this type of literature in the 16th century. From him, the style is called "Bernesque poetry". In Bernesque poets, we see a similar phenomenon to Orlando furioso. Art for art's sake inspired Berni, as well as Antonio Francesco Grazzini and other lesser writers. It's true that they often enjoyed praising low and disgusting things and mocking what was noble and serious. Bernesque poetry clearly reflects the religious and moral skepticism common in Italian society in the 16th century. This skepticism stopped the Reformation in Italy. The Bernesque poets, especially Berni himself, sometimes used a satirical tone. But their work wasn't true satire. Pure satirists, however, were Antonio Vinciguerra, Lodovico Alamanni, and Ariosto. Ariosto was superior for his elegant style and a certain frankness that turned into malice, especially when he talked about himself.

In the 16th century, there were quite a few didactic (teaching) works. In his poem Le Api, Giovanni di Bernardo Rucellai approaches the perfection of Virgil. His style is clear and light. He makes his book more interesting by often referring to events of his time. The most important didactic work, however, is Castiglione's Cortigiano. In it, he imagines a discussion in the palace of the dukes of Urbino between knights and ladies about what qualities a perfect courtier needs. This book is valuable for showing the intellectual and moral state of the highest Italian society in the first half of the 16th century.

Of the novelists of the 16th century, the two most important were Grazzini and Matteo Bandello. Grazzini was playful and strange, while Bandello was serious and formal. Bandello was a Dominican friar and a bishop. Despite this, his novels were very loose in subject, and he often made fun of the clergy of his time.

At a time when admiration for style and desire for classical elegance were so strong, much attention was naturally paid to translating Latin and Greek authors. Among the many translations of the time, those of the Aeneid and Pastorals by Annibale Caro are still famous. Also notable are translations of Ovid's Metamorphoses by Giovanni Andrea dell' Anguillara, Apuleius's The Golden Ass by Firenzuola, and Plutarch's Lives and Moralia by Marcello Adriani.

The 17th Century: A Time of Decline

From about the Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis (1559), which began centuries of foreign rule over Italy, Italian literature entered a period of decline. Tommaso Campanella was tortured by the Inquisition, and Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake. Cesare Balbo said that if a nation is happy with peace without progress, nobility with titles but no power, princes with rule but no real independence, and writers who please their time but are forgotten later, then no period was as happy for Italy as the 140 years from the Peace of Cateau Cambrésis to the War of the Spanish Succession. This period is known as the Secentismo. Its writers used exaggeration. They tried to create effect with what is called mannerism or barocchism in art. Writers competed in using metaphors, affectations, hyperbole, and other strange styles, moving away from clear thought.

Marinism: Exaggerated Style

The leader of the Secentisti school was Giambattista Marino of Naples, born in 1569. He is known for his long poem, L'Adone. He used the most extreme metaphors, forced contrasts, and far-fetched ideas. He strung contrasts together, filling whole stanzas without a break. Claudio Achillini of Bologna followed Marino, but his style was even more exaggerated. Almost all poets of the 17th century were influenced by Marinism. Carlo Alessandro Guidi, though not as extreme as Marino, was bombastic and wordy. Fulvio Testi was artificial and affected. Yet, both Guidi and Testi were influenced by another poet, Gabriello Chiabrera, born in Savona in 1552. He loved the Greeks and created new meters, imitating Pindar. He wrote on religious, moral, historical, and love topics. Chiabrera, though elegant in form, tried to hide a lack of substance with poetic decorations. Nevertheless, Chiabrera's school marked an improvement. Sometimes he showed lyrical talent, but it was wasted on his literary environment.

Arcadia: A Return to Simplicity?

People began to believe that literature needed a new form to be restored. So, in 1690, the Academy of Arcadia was founded. Its founders were Giovanni Mario Crescimbeni and Gian Vincenzo Gravina. It was called Arcadia because its main goal was to imitate the simple life of ancient shepherds, who supposedly lived in Arcadia in a golden age. The Secentisti had gone too far with their desire for novelty. The Arcadians proposed to return to truth, always singing about simple pastoral subjects. This was just replacing one artificial style with another. They went from grand words to weakness, from exaggeration to triviality, from wordiness to over-refinement. The Arcadians' poems fill many volumes. They are made up of sonnets, madrigals, canzonette, and blank verse. The most distinguished sonnet writer was Felice Zappi. Among song authors, Paolo Rolli was famous. Carlo Innocenzo Frugoni was more famous than all the others, a man with a rich imagination but shallow intellect. Most members of the Arcadia were men, but at least one woman, Maria Antonia Scalera Stellini, was elected for her poetic skills.

Vincenzo da Filicaja, a Florentine, had lyrical talent. Especially in his songs about Vienna besieged by the Turks, he rose above the faults of his time. But even in his work, we clearly see rhetorical tricks and false ideas. In general, all lyric poetry of the 17th century had the same flaws, to different degrees. These flaws can be summarized as a lack of feeling and exaggerated style.

Independent Thinkers: New Ideas

While Italy's political and social conditions in the 17th century seemed to extinguish all intelligence, some strong and independent thinkers emerged. These included Bernardino Telesio, Lucilio Vanini, Giordano Bruno, and Tommaso Campanella. They explored philosophy in new ways and opened the path for the scientific achievements of Galileo Galilei. Galileo was not only a great scientist but also important in literary history. He studied Ariosto and seemed to put that great poet's qualities into his prose: clear and frank expression, precision, ease, and elegance.

Another sign of revival, a rebellion against the low quality of Italian social life, appeared in satire. Especially notable were Salvator Rosa and Alessandro Tassoni. Rosa, born in 1615 near Naples, was a painter, musician, and poet. As a poet, he mourned his country's sad state. He expressed his feelings with "generous rebukes," as another satirist, Giuseppe Giusti, said. He was a pioneer of modern times. Tassoni showed independent judgment amidst widespread obedience. His Secchia Rapita proved he was an excellent writer. This is a heroic comic poem, both an epic and a personal satire. He was bold enough to attack the Spanish in his Filippiche, urging Duke Charles Emmanuel of Savoy to continue the war against them.

Agricultural Writings

Paganino Bonafede in Tesoro de rustici gave many farming instructions. This started a type of agricultural poetry later fully developed by Luigi Alamanni in his Coltivazione, by Girolamo Baruffaldi in the Canapajo, by Rucellai in Le Api, by Bartolomeo Lorenzi in the Coltivazione de' monti, and by Giambattista Spolverini in the Coltivazione del riso.

The 18th Century: Reason and Reform

In the 18th century, Italy's political situation began to get better under rulers like Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor. These rulers were influenced by philosophers. These philosophers, in turn, were part of a general movement of ideas across Europe, sometimes called The Enlightenment.

History and Society: Vico, Muratori, and Beccaria

Giambattista Vico showed the awakening of historical awareness in Italy. In his Scienza nuova, he studied the laws that govern human progress and how events unfold. By studying human psychology, he tried to figure out the "common nature of nations." These were the universal laws of history that explain how civilizations rise, flourish, and fall. The same scientific spirit that inspired Vico led to a different kind of research: studying the sources of Italian civil and literary history.

Lodovico Antonio Muratori collected chronicles, biographies, letters, and diaries of Italian history from 500 to 1500 in his Rerum Italicarum scriptores. He also discussed difficult historical questions in Antiquitates Italicae medii aevi. Then he wrote Annali d'Italia, carefully narrating facts from real sources. Muratori's partners in historical research were Scipione Maffei of Verona and Apostolo Zeno of Venice. In his Verona illustrata, Maffei left a treasure of knowledge that was also an excellent historical study. Zeno added much to the knowledge of literary history in his Dissertazioni Vossiane. Girolamo Tiraboschi and Count Giammaria Mazzucchelli of Brescia focused on literary history.

While the new spirit of the times led to studying historical sources, it also encouraged looking into economic and social laws. Ferdinando Galiani wrote about money. Gaetano Filangieri wrote Scienza della legislazione. Cesare Beccaria, in his Trattato dei delitti e delle pene, helped reform the justice system and promoted ending torture.

Metastasio and Melodrama

The reform movement aimed to get rid of artificial styles and return to truth. Apostolo Zeno and Pietro Metastasio (whose Arcadian name was Pietro Trapassi) tried to make melodrama and reason compatible. Metastasio gave fresh expression to emotions, a natural flow to dialogue, and some interest to the plot. If he hadn't constantly fallen into unnatural over-refinement and sentimentality, and frequent anachronisms, he might be considered the most important writer of opera seria libretti and the first dramatic reformer of the 18th century.

Carlo Goldoni: Comedy of Character

Carlo Goldoni, a Venetian, overcame resistance from the old popular comedy style, with its masks like pantalone and harlequin. He created the comedy of character, following Molière's example. Goldoni's characters are often simple, but he wrote lively dialogue. He produced over 150 comedies and didn't have time to perfect them. But for a comedy focusing on character, we must go straight from Machiavelli's Mandragola to Goldoni. Goldoni's talent for drama is shown by how he took almost all his characters from Venetian society, yet gave them endless variety. Many of his comedies were written in Venetian.

His works include some of Italy's most famous and beloved plays. Audiences have admired Goldoni's plays for their clever mix of wit and honesty. His plays showed his contemporaries images of themselves. They often dramatized the lives, values, and conflicts of the growing middle classes. Goldoni also wrote under the pen name Polisseno Fegeio, Pastor Arcade, which he said the "Arcadians of Rome" gave him.

One of his best-known works is the comic play Servant of Two Masters. It has been translated and adapted many times internationally. In 2011, Richard Bean adapted the play for the National Theatre of Great Britain as One Man, Two Guvnors. Its popularity led to a transfer to the West End and in 2012 to Broadway. The film Carlo Goldoni – Venice, Grand Theatre of the World, directed by Alessandro Bettero, was released in 2007.

Giuseppe Parini: Satire and Classical Style

The leading figure of the 18th-century literary revival was Giuseppe Parini. Born in a Lombard village in 1729, he was educated in Milan. As a youth, he was known among Arcadian poets as Darisbo Elidonio. Even as an Arcadian, Parini showed originality. In a collection of poems published at age twenty-three, he showed his ability to take scenes from real life. In his satirical pieces, he openly opposed his own times. These poems, though influenced by others, showed a strong desire to challenge literary traditions. Improving on his youthful poems, he showed himself an innovator in his lyrics. He rejected Petrarchism, Secentismo, and Arcadia, which he thought had weakened Italian art. In the Odi, the satirical tone is already present. But it comes out more strongly in Del giorno. In this work, he pretends to teach a young Milanese nobleman all the habits of high society. He exposes all its silly trivialities and subtly mocks the uselessness of aristocratic customs. Dividing the day into four parts (morning, noon, evening, and night), he describes the small things that filled them. The book thus gains significant social and historical value. As an artist, he went straight back to classical forms, aiming to imitate Virgil and Dante. He opened the way for the school of Vittorio Alfieri, Ugo Foscolo, and Vincenzo Monti. As a work of art, Giorno is wonderful for its delicate irony. The verse has new harmonies. Sometimes it is a little harsh, as a protest against the Arcadian monotony.

Linguistic Purism: The Language Debate

While strong political passions raged, and brilliant writers of the new classical and patriotic school were at their peak, a question arose about language purity. In the second half of the 18th century, the Italian language was full of French expressions. There was great indifference about proper and elegant style. Prose needed to be restored for national dignity. People believed this could only be done by returning to the writers of the 14th century, the "golden trecentisti" (14th-century writers), or to the classics of Italian literature. One of the leaders of this new school was Antonio Cesari of Verona. He republished old authors and brought out a new edition of the Vocabolario della Crusca. He wrote a paper Sopra lo stato presente della lingua italiana. He tried to establish the dominance of Tuscan and of the three great writers: Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio. Following this principle, he wrote several books, carefully copying the trecentisti. But patriotism in Italy always had a local flavor. So, against this Tuscan dominance, a Lombard school arose. It rejected Tuscan and, using Dante's De vulgari eloquentia, returned to the idea of the "illustrious language."

This was an old debate, fiercely argued in the 16th century by Benedetto Varchi and others. Now, the question was raised again. At the head of the Lombard school were Monti and his son-in-law Count Giulio Perticari. This led Vincenzo Monti to write Proposta di alcune correzioni ed aggiunte al vocabolario della Crusca. In it, he attacked the Tuscan focus of the Accademia della Crusca. He did so in a graceful and easy style, creating some of the most beautiful prose in Italian literature. Perticari, who was less intelligent, made the issue narrower and more intense in two books. The dispute about language joined literary and political debates, and all of Italy took part.

A patriot, a classicist, and a purist all at once was Pietro Giordani, born in 1774. He was almost a summary of the literary movement of the time. His whole life was a fight for liberty. Learned in Greek and Latin authors, and in the Italian trecentisti, he left only a few writings. But they were carefully crafted in style, and his prose was greatly admired. Giordani closes the literary period of the classicists.

Minor Writers of the 18th Century

Gasparo Gozzi's satire was less grand, but aimed at the same goal as Parini's. In his Osservatore, similar to Joseph Addison's Spectator, and in his Gazzetta veneta, he gently criticized vices using allegories and new ideas. Gozzi's satire has a slight resemblance to Lucian's style. Gozzi's prose is graceful and lively, but it imitates 14th-century writers. Another satirical writer of the first half of the 18th century was Giuseppe Baretti of Turin. In a journal called the Frusta letteraria, he harshly criticized works being published in Italy. He had learned much from traveling. His long stay in Britain helped him develop an independent mind. The Frusta was the first book of independent criticism, especially against the Arcadians and pedants.

In 1782, Giovanni Battista Niccolini was born. In literature, he was a classicist. In politics, he was a Ghibelline, a rare exception in his birthplace, Guelph Florence. In imitating Aeschylus, and in writing Discorsi sulla tragedia greca, Niccolini showed his strong devotion to ancient literature. In his tragedies, he freed himself from Alfieri's strictness and partly approached English and German tragic authors. He almost always chose political subjects, trying to keep the love of liberty alive in his countrymen. Examples include Nabucco, Antonio Foscarini, and Giovanni da Procida. He attacked papal Rome in Arnaldo da Brescia, a long tragic piece not suitable for acting, and more epic than dramatic. Niccolini's tragedies show a rich lyrical talent rather than dramatic genius. He deserves credit for defending liberal ideas and opening a new path for Italian tragedy.

Carlo Botta, born in 1766, witnessed French looting in Italy and Napoleon's harsh rule. He wrote a History of Italy from 1789 to 1814. Later, he continued Guicciardini's History up to 1789. He wrote in the style of Latin authors, trying to imitate Livy. He used long, grand sentences in a style that aimed to be like Boccaccio's. He cared little about historical facts, only about delivering academic prose for his country's benefit. Botta wanted to be classical in a style that was no longer possible, so he completely failed to achieve his literary goal. His fame is only that of a noble and patriotic man. Not as bad as his two histories of Italy is his Guerra dell'indipendenza americana.

Close to Botta comes Pietro Colletta, a Neapolitan born nine years after him. In his Storia del reame di Napoli dal 1734 al 1825, he also aimed to defend Italy's independence and liberty in a style borrowed from Tacitus. He succeeded better than Botta. He has a fast, brief, energetic style that makes his book engaging. But it is said that Pietro Giordani and Gino Capponi corrected it for him. Lazzaro Papi of Lucca, author of Commentari della rivoluzione francese dal 1789 al 1814, was somewhat similar to Botta and Colletta. He was also a historian in the classical style and treated his subject with patriotic feeling. But as an artist, he perhaps surpassed the other two.

Alberto Fortis started the Morlachist literary movement in Italian and Venetian literature with his 1774 work Viaggio in Dalmazia ("Journey to Dalmatia").

The Revolution: Patriotism and Classicism

The ideas behind the French Revolution of 1789 gave a special direction to Italian literature in the second half of the 18th century. Love of liberty and desire for equality created literature focused on national goals. It aimed to improve the country by freeing it from both political and religious control. Italians who wanted political freedom believed it was linked to an intellectual revival. They thought this could only happen by returning to ancient classicism. This was a repeat of what happened in the first half of the 15th century.

Vittorio Alfieri: Fighting Tyranny

Vittorio Alfieri was inspired by two main ideas: patriotism and classicism. He admired the Greek and Roman idea of popular liberty fighting against tyranny. He took the subjects of his tragedies from the history of these nations. He made his ancient characters speak like revolutionaries of his time. He rejected the Arcadian school, with its wordiness and triviality. His goal was to be brief, concise, strong, and sharp. He aimed for the sublime, not the lowly or pastoral. He saved literature from Arcadian emptiness, guiding it towards a national purpose. He armed himself with patriotism and classicism.

Alfieri owes his high reputation mainly to his plays. Before him, the Italian language, so harmonious in Petrarch's Sonnets and so energetic in Dante's Commedia, was always weak and dull in dramatic dialogue. The overly academic tragedies of the 16th century were followed by plays with extreme emotions and unlikely plots. The huge success of Maffei's Merope in the early 18th century was probably due more to comparison with these bad plays than to its own merit. In this decline of tragic taste, the appearance of Alfieri's tragedies was perhaps the most important literary event in Italy during the 18th century.

Vincenzo Monti: The Artistic Patriot

Vincenzo Monti was also a patriot, but in his own way. He didn't have one deep feeling that controlled him. Instead, his feelings changed easily, which was his main characteristic. But each of these feelings was a new form of patriotism that replaced an old one. He saw danger to his country in the French Revolution. He wrote Pellegrino apostolico, Bassvilliana, and Feroniade. Napoleon's victories led him to write Pronreteo and Musagonia. In his Fanatismo and Superstizione, he attacked the papacy. Afterwards, he praised the Austrians. Thus, every major event made him change his mind. This might seem unbelievable, but it's easily explained. Monti was, above all, an artist. Everything else about him could change. Knowing little Greek, he managed to translate the Iliad in a way remarkable for its Homeric feeling. In his Bassvilliana, he is on par with Dante. In him, classical poetry seemed to revive in all its grand beauty.

Ugo Foscolo: Passionate Patriot

Ugo Foscolo was an eager patriot, inspired by classical models. His Lettere di Jacopo Ortis, inspired by Goethe's The Sorrows of Young Werther, are a love story mixed with patriotism. They contain a strong protest against the Treaty of Campo Formio and an outpouring of Foscolo's own feelings about an unhappy love affair. His passions were sudden and strong. Ortis came from one of these passions, and it is perhaps the best and most sincere of all his writings. He is still sometimes overly formal and dramatic, but less so than, for example, in his lectures Dell'origine e dell'ufficio della letteratura. Overall, Foscolo's prose is wordy and affected. It reflects the character of a man who always tried to appear dramatic. This was a flaw of the Napoleonic era. People hated anything common, simple, or natural; everything had to take on a heroic form. In Foscolo, this tendency was extreme. The Sepolcri, his best poem, was prompted by strong feeling. Its mastery of versification shows amazing art. It has very unclear passages, where it seems even the author didn't have a clear idea. He left three hymns to the Graces unfinished. In them, he sang of beauty as the source of courtesy, high qualities, and happiness. Among his prose works, his translation of Laurence Sterne's Sentimental Journey holds a high place. He was deeply affected by Sterne. He went into exile in England and died there. For English readers, he wrote some Essays on Petrarch and on the texts of the Decamerone and Dante. These are remarkable for their time and may have started a new kind of literary criticism in Italy. Foscolo is still greatly admired, and for good reason. The men who led the revolution of 1848 grew up reading his work.

19th Century: Romanticism and Unification

The Romantic movement had its voice in the Conciliatore magazine, started in 1818 in Milan. Its staff included Silvio Pellico, Ludovico di Breme, and Alessandro Manzoni. All were influenced by the ideas of Romanticism, especially from Germany. In Italy, literary reform took a different path.

Alessandro Manzoni: The Betrothed

The main leader of this reform was Alessandro Manzoni. He defined the goals of the new school. He said it aimed to discover and express "historical truth" and "moral truth." These were not just goals, but the broadest and eternal source of beauty. Realism in art is what defines Italian literature from Manzoni onwards.

Promessi Sposi (The Betrothed) is the work that made him famous forever. Manzoni achieved more than just a historical novel. He created a truly realistic work of art. The reader's attention is completely focused on the powerful and real characters. From the greatest to the least, they are wonderfully believable. Manzoni can show a character in all its details and follow it through different stages. Don Abbondio and Renzo are as perfect as Azzeccagarbugli and Il Sarto. Manzoni delves into the deepest parts of the human heart. He brings out the most subtle psychological reality. This is where his greatness lies, recognized first by his fellow genius, Goethe. The Betrothed is generally ranked among the masterpieces of world literature. The novel is also a symbol of the Italian Risorgimento (unification). This is because of its patriotic message and its key role in developing the modern, unified Italian language.

As a poet, he also had flashes of genius. Especially in his ode about Napoleon, Il Cinque Maggio, and where he describes human emotions, like in some stanzas of the Inni and the chorus of the Adelchi.

Giacomo Leopardi: The Melancholy Poet

The great poet of this age was Giacomo Leopardi. He was born thirteen years after Manzoni in Recanati, into a noble family. He became so familiar with Greek authors that he later said Greek thought was clearer and more alive to him than Latin or even Italian. Solitude, sickness, and family control made him deeply melancholic. He became completely religiously skeptical, seeking comfort only in art. He was also an excellent prose writer. In his Operette Morali—dialogues and discussions marked by a cold, bitter smile at human fate that chills the reader—the clarity of style, simplicity of language, and depth of ideas are such that he is perhaps not only the greatest lyrical poet since Dante, but also one of the most perfect prose writers in Italian literature. He is widely seen as one of the most radical thinkers of the 19th century. Italian critics often compare him to his older contemporary Alessandro Manzoni, despite their "diametrically opposite positions." The strong lyrical quality of his poetry made him a central figure in European and international literature.

History and Politics in the 19th Century