History of construction facts for kids

The history of construction is all about how people have built things over time. It looks at the tools, methods, and systems used to create shelters and other structures. This history connects to many fields like structural engineering (how buildings stand up), civil engineering (designing public works), and even how city growth and population growth have changed building needs. It helps us understand both old and new ways of building, plus the materials and tools used.

Building is one of the oldest human activities, starting around 4000 BC because people needed shelter. Over time, construction has changed a lot. Key ideas include making buildings last longer, building them taller and wider, controlling the inside environment better, and using more energy for building.

Contents

- Prehistoric Era: Early Builders

- Civilizations: Building Empires

- Middle Ages: Castles and Cathedrals

- Renaissance: The Architect's Rise

- Early Modern Era: Science and Industry Begin

- Industrial Revolution: Modern Construction Begins

- Studying Construction History

- See also

Prehistoric Era: Early Builders

Stone Age: Simple Shelters

During the Stone Age, early humans were hunter-gatherers. They moved around a lot, so their homes were usually temporary. Because of this, not many old buildings from this time have survived. However, some scientists believe the oldest known building is a 1.8-million-year-old stone circle found in Olduvai Gorge. It might have been a simple windbreak to block the wind.

Later, in the Mesolithic era, people started to farm. Hunter-gatherers still built temporary shelters, especially for hunting. The oldest known man-made shelter is from 400,000 B.C. in Terra Amata, France. It was a home for hunters.

Neolithic Era: Settling Down

By the Neolithic era, also called the New Stone Age, humans began to farm and raise animals. This meant they stopped moving around and started building permanent homes and even cities. Besides living in caves and using rock shelters, the first buildings were simple tents, like the Inuit's tupiq, and huts. Huts were built for protection from weather, like pit-houses, or for safety, like crannogs.

People built their own shelters using materials found nearby and traditional designs. For example, the first bridges were probably just wooden logs placed across a stream. Later, they became more complex timber trackways.

Building Materials and Tools

Prehistoric people made tools from bone, ivory, antler, animal hide, stone, wood, grass, and early metals like gold, copper, and silver. They made tools for cutting (hand axe, chopper, adze), scraping (flake tool), pounding, piercing, and lifting. For building, they used bones (like mammoth ribs), hide, stone, metal, bark, bamboo, and even animal dung.

They also used bricks and lime plaster. For example, mud bricks and clay mortar from 9000 BC were found in Jericho. These mudbricks were shaped by hand, not with wooden molds.

Building Techniques

Without metal tools, people were limited in what materials they could use. But they were very clever! They built amazing stone structures using dry stone walling, where stones fit together without mortar. Skara Brae in Scotland is a great example of a complete Neolithic village built this way. Another settlement, Göbekli Tepe, has T-shaped limestone pillars carved with flint points. The corbelled roof of Newgrange (around 3,200 BC) shows that this type of arch was used very early.

One of the biggest buildings of this time was the Neolithic long house. These were long, narrow timber homes built by early farmers in Europe. Since only the lowest parts of the walls and post holes remain, we can only guess what the upper parts looked like.

The most famous Neolithic structure in Western Europe is Stonehenge. Some archaeologists think it shows how timber building methods were copied in stone. It uses post and lintel construction, with huge sandstone lintels (horizontal stones) placed on top of upright stones. These stones were joined using mortise and tenon joints, like wooden pegs. The builders of Stonehenge also had advanced surveying skills to make the stone circles so precise.

Gallery of Neolithic Tools

Copper Age and Bronze Age: Metal Tools Emerge

Copper started to be used before 5,000 BC. It was one of the first metals used for tools, along with gold, silver, and lead. Copper was soft, strong, and didn't rust easily, making it much better than stone for tools. During this time, the saw was invented and used for building.

Around 3,100 BC, people learned to mix metals to make alloys. Bronze was made by adding tin to copper, and brass by adding zinc. Bronze could be molded into different shapes and melted down if damaged, leading to many new tools. Copper and bronze tools were sharper and lasted longer than stone tools. Egyptians even used copper and bronze points to cut soft stone for quarrying and carving.

During the Copper Age, the ancient Chinese invented fired bricks as early as 4400 BC. In Chengtoushan, fired bricks were used for house floors. Mesopotamians used clay for sewer pipes around 4000 BC. The city of Uruk had latrines with raised fired brick platforms around 3200 BC. The Ziggurat of Ur was built with mudbricks covered in burnt bricks set in bitumen.

The wheel was invented by the Sumerians in the Copper Age, but it wasn't used for transport until around 3500 BC. Heavy loads were moved on boats, sledges (like primitive sleds), or rollers. The oldest measuring rod, made of copper-alloy, dates back to 2650 BC from the Sumerian city of Nippur.

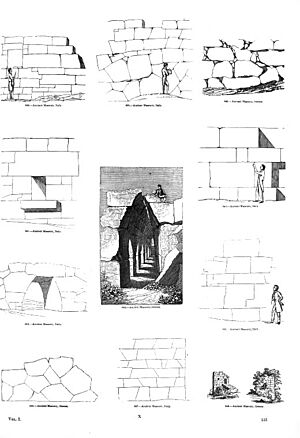

The post and lintel building method became popular with the Egyptians around 3100 BC. They used it to build temples and the Great Pyramid of Giza (around 2560 BC). The Greeks and Romans later used this technique too, as seen in the Tomb of Agamemnon (around 1250 BC). Cyclopean masonry, using huge, rough stones, was also common, especially by the Mycenaeans in structures like the Arkadiko Bridge.

Iron Age: Stronger Tools

The Iron Age began around 1200 BC and ended around 500 BC. Iron was sometimes used before, but it wasn't as good as bronze. That changed when people learned to make steel by mixing iron and carbon. Steel could be made very hard and durable, leading to much better tools like hammers, chisels, knives, and axes.

In the United Kingdom during the Iron Age, the most common buildings were roundhouses. These were made from stone or wooden posts, with walls of wattle-and-daub (woven branches covered in mud) and a conical thatched roof. Archaeologists believe the wooden walls were shaped using side axes.

Civilizations: Building Empires

Ancient Mesopotamia: Cities of Mud-Brick

The earliest large buildings we have evidence for are from ancient Mesopotamia. While small homes have mostly disappeared, later civilizations built huge palaces, temples, and ziggurats. They used materials that lasted, so many parts of these structures are still around. Building great cities like Uruk and Ur showed major technical skills. The Ziggurat of Ur is a famous example, even after being rebuilt. Another is the ziggurat at Chogha Zanbil in modern Iran. Cities needed new technologies like drains for waste and paved streets.

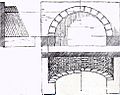

Archaeological finds show that they built vaults with slanted bricks, like at Tell al-Rimah in Iraq.

Building Techniques and Materials

The main building material was mud-brick, shaped in wooden molds, similar to adobe bricks. Bricks came in many sizes and shapes. They were laid in complex patterns. Drawings from later periods show that buildings were planned using brick sizes. By 3500 BC, fired bricks were used, and records show that building work was divided into many different tasks and trades. Fired bricks and stone were used for pavements.

Building was often part of complex rituals, even for laying the first bricks. The arch was used by these civilizations, not just invented by the Romans as some believe. Later Mesopotamian civilizations, especially in Babylon and Susa, became very skilled at using glazed brickwork. They decorated buildings with colorful glazed brick reliefs, which you can see in museums today.

-

Detail of the Ishtar Gate (575 BC) showing the exceptionally fine glazed brickwork of the later period. Glazed bricks have been found from the 13th century B.C.

-

Babylon,the archaeological site in 1932, before major reconstruction work undertaken by Sadam Hussein

Building Code

The Code of Hammurabi, from the Babylonians, is known to have the earliest written building rules.

Ancient Egypt: Pyramids and Stone Wonders

Unlike Mesopotamia, which built with bricks, the pharaohs of Egypt built massive structures out of stone. The dry climate has helped preserve many of these ancient buildings.

Materials

Adobe (sun-baked mud brick) was used for smaller buildings and regular homes. It's still common in rural Egypt today. The hot, dry climate was perfect for mud-brick, which washes away in rain. The Ramesseum in Thebes, Egypt is a great example of mud-brick construction. Many mud-brick vaults also survive, built with slanted layers to avoid needing temporary supports.

The grandest buildings were made of stone, often huge blocks. How these massive blocks were moved for pyramids and temples is still debated. Some think the largest ones might have been made from concrete, not cut stone.

Building Technology

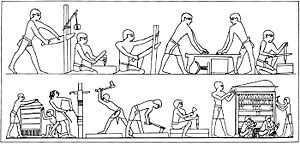

Even though Egyptians built amazing structures, they used relatively simple technology. They didn't use wheels or pulleys as far as we know. They moved huge stones long distances using rollers, ropes, and sledges pulled by many workers. Ancient Egyptians are credited with inventing the ramp, lever, lathe, oven, ship, paper, irrigation system, window, awning, door, glass, a type of plaster, the bath, lock, shadoof (a water-lifting device), weaving, a standard measurement system, geometry, silo, stone drilling, the saw, early steam power, scale drawings, enameling, veneer, plywood, and the rope truss. Since no Egyptian building manuals exist, people guess how stones were lifted. Most ideas involve ramps.

Imhotep, who lived around 2650–2600 BC, is known as the first recorded architect and engineer.

Achievements

The pyramids are impressive because of their huge size and the incredible number of people needed to build them. The Great Pyramid of Giza was the tallest structure in the world for 3800 years! The main challenges were moving blocks, sometimes over long distances, and placing them precisely. It's believed that skilled builders were respected, but many laborers were needed for the heavy work.

How the pyramids were built has been studied a lot.

-

Great Pyramid of Giza, the tallest building in the world for over 3800 years

Ancient Greece: Temples and Precision

Like the Egyptians and Mesopotamians, the ancient Greeks built most everyday buildings from mud brick, which didn't last. However, many stone structures survive, some in good condition. The most famous are the Greek Temples. The Greeks made many advances in technology, including plumbing, the spiral staircase, central heating, urban planning, the water wheel, and the crane.

The oldest construction drawing is found in the Temple of Apollo at Didyma. An unfinished stone wall has etched outlines of columns and moldings. This drawing was never erased because the wall wasn't finished, giving us a rare look at ancient building plans.

We don't have many timber structures (like roofs or floors) left, so we know less about how they were built. Spans were usually small, suggesting simple beam and post structures on stone walls. For longer spans, Romans definitely used timber roof trusses, but it's unclear if Greeks invented them. Before 650 BC, famous Greek temples were made of wood. After that, they started using stone. This process of copying timber structures in stone is called petrification.

Fired clay was mostly used for roofing tiles and decorations, which were quite fancy. These tiles allowed for the low roof pitch seen in Greek architecture. Fired bricks began to be used with lime mortar. Important buildings had stone roof tiles that looked like terracotta ones. While later cultures built stone buildings with thin outer layers over rubble, the Greeks used large, cut blocks joined with metal clamps. This was slow and expensive. The metal clamps often failed due to rust.

Greek buildings mostly used a simple beam and column system, without many vaults or arches. This limited how wide they could build. However, the Greeks did build some groin vaults, arch bridges, and, with the Egyptians, the first high-rise building: the Lighthouse of Alexandria, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Greek math was advanced, and they understood pulleys. This would have helped them build jibs and cranes to lift heavy stones. Their surveying skills were amazing, allowing them to make the incredibly precise optical corrections in buildings like the Parthenon. Simpler decorations, like fluting on columns, were usually carved after the column pieces were in place.

The ancient Greeks never developed the strong mortars that became important in Roman building.

Roman Empire: Concrete and Grand Scale

We know a lot about Roman building because so much of it still exists, including complete buildings like the Pantheon, Rome and well-preserved ruins at Pompeii. The first surviving book on architecture is by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, which talks a lot about building techniques. His writings showed the difference between a master builder and an architect.

Materials

The Romans' big breakthrough in building materials was using a special hydraulic lime mortar called Roman cement. Earlier cultures used lime mortars, but the Romans added volcanic ash (called pozzolana). This made the mortar harden even underwater, creating a self-healing cement. This gave them a strong material for thick walls. They built the outer layers of walls with brick or stone, then filled the middle with huge amounts of concrete. The brickwork acted like a permanent mold. Later, they used wooden molds that were removed after the concrete dried.

The Temple of Vesta in Tivoli, Italy (1st century BC) is an example of a temple made of Roman concrete. This concrete was just rubble and mortar. It was cheap and easy to make, and didn't need highly skilled workers. This allowed Romans to build on a huge scale. They used concrete not just for walls, but also for arches, barrel vaults, and huge domes. They even developed hollow pots for their domes and clever heating and ventilation systems for their public baths.

The Romans used bronze instead of wood for the roof trusses of the Pantheon's portico. These bronze trusses were unique, but in 1625, Pope Urban VIII replaced them with wood and melted the bronze for other uses. Romans also made bronze roof tiles.

Lead was used for roof coverings and water pipes. That's why we call it "plumbing" – from the Latin word for lead, plumbum. Romans also used glass in buildings, with colored glass in mosaics and clear glass for windows. Glass became common in public buildings. Hypocausts, a type of central heating, used raised floors heated by wood or coal fires.

Organization of Labor

The Romans had trade guilds. Most building work was done by slaves or free men. Using slave labor certainly lowered costs and helped them build so much. Romans wanted to build very quickly, usually within two years. For huge structures, this meant using vast numbers of workers.

Technology

The Romans invented the waterwheel, sawmill, and the arch. They also started using glass in architecture around 100 CE and even used double glazing for insulation. Roman roads included corduroy roads (made of logs) and paved roads, sometimes on raft or pile foundations, and bridges. Vitruvius described many Roman machines. They developed advanced timber cranes that could lift heavy weights very high. The heaviest they could lift was about 100 tons. Trajan's Column in Rome has some of the largest stones ever lifted in a Roman building, and engineers still aren't sure exactly how it was done.

Roman building skills extended to bridges, aqueducts, and covered amphitheatres. Their sewer and water systems were amazing, and some still work today. We know very little about Roman timber roof structures, as none have survived. They likely built triangulated roof trusses to achieve their huge spans, some over 30 meters long.

Ancient China: The Great Wall and Timber Frames

China was a major center for building methods and styles in eastern Asia. Many building techniques in the Far East came from China. A famous example is the Great Wall of China, built between the 7th and 2nd centuries BC. The Great Wall was made with rammed earth, stones, and wood, and later bricks and tiles with lime mortar. Wooden gates blocked passages. The oldest examples of mortise and tenon woodworking joints (where one piece fits into a hole in another) were found in China, dating back to about 5000 BC.

The Yingzao Fashi is the oldest complete technical manual on Chinese architecture. Chinese builders followed state rules for thousands of years, so many old buildings still standing were built using methods from the 11th century. Chinese temples usually have wooden timber frames on an earth and stone base. The oldest wooden building is the Nanchan Temple (Wutai) from 782 AD. However, Chinese temple builders often rebuild wooden temples, so parts of these old buildings can be from different times. Traditional Chinese timber frames don't use trusses but rely on post and lintel construction. An important architectural element is the dougong bracket set, which supports the roof. The Songyue Pagoda is the oldest brick pagoda, dating to 523 AD. It was built with yellow fired bricks and clay mortar, with twelve sides and fifteen levels of roofs. The Anji Bridge is the world's oldest open-spandrel stone segmental arch bridge, built in 595–605 AD. It's made of sandstone joined with dovetail iron joints.

Most of the Great Wall sections you see today were built with bricks and cut stone blocks. Where these weren't available, builders used tamped earth, uncut stones, wood, and even reeds. Wood was used for forts and as an extra material. If local timber wasn't enough, it was brought in.

Stone Great Wall Sections

In mountain areas, workers quarried stone to build the Great Wall. They used the mountains as foundations. The outer layer of the wall was built with stone blocks (and bricks), and the inside was filled with uncut stone and anything else available.

Soil Great Wall Sections

On flat lands, Great Wall workers used local soil (sand, loess, etc.) and packed it tightly into layers. The Jiayuguan section of the Great Wall in west China was mostly built with dusty loess soil.

Sand (and Reed/Willow) Great Wall Sections

Sand doesn't stick together well, so it was used as a filler between layers of reeds and willow to build parts of the wall. In the desert areas around Dunhuang, clever builders used reeds and willow from rivers and oases to build a strong wall. The Jade Gate Pass (Yumenguan) Great Wall Fort was built with 20-cm layers of sand and reed, reaching an impressive 9 meters high.

Brick Great Wall Sections

The Ming Dynasty Great Wall was mostly built with bricks. To make a strong wall, they used lime mortar. Workers built brick and cement factories near the wall using local materials.

Middle Ages: Castles and Cathedrals

The Middle Ages in Europe lasted from the 5th to the 15th centuries AD. After the Roman Empire fell, building activities and technology slowed down. Most construction was done by the Roman Catholic Church. Training and education for crafts became very important, and craft guilds were formed. There were three levels of skill: master, journeyman, and apprentice.

Fortifications, castles, and cathedrals were the biggest building projects. Many Roman building techniques were lost at the start of the Middle Ages. But some, like using iron ring-beams, were used in the Palatine Chapel at Aachen around 800 AD. Stone building revived in the 9th century, and the Romanesque style began in the late 11th century. Also notable are the stave churches in Scandinavia, built entirely of wood.

Materials

Most buildings in Northern Europe were made of timber until about 1000 AD. In Southern Europe, adobe was still common. Bricks continued to be made in Italy, but elsewhere, the skill of brick-making mostly disappeared. Roofs were usually thatched. Houses were small and grouped around a large shared hall. Monasteries helped spread more advanced building techniques. The Cistercians might have brought brick-making back to areas like the Netherlands and Germany, leading to Backsteingotik (Brick Gothic). Brick remained a popular material for important buildings in these areas. Elsewhere, buildings were typically timber or, if affordable, stone. Medieval stone walls had cut blocks on the outside and rubble filling inside, held together with weak lime mortars. These mortars didn't harden well, and the settling of the rubble in Romanesque and Gothic walls is still a problem today.

Design

There were no standard building textbooks in the Middle Ages. Master craftsmen passed on their knowledge through apprenticeships and from father to son. Trade secrets were kept secret because they were how craftsmen earned a living. Drawings only exist from the later period. Parchment was too expensive, and paper didn't appear until the end of this time. Models were used for designing structures, sometimes built to large scales. Details were often drawn full-size on tracing floors.

Techniques

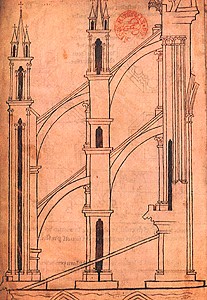

Romanesque buildings (600–1100 AD) had timber roofs or stone barrel vaults covered by timber roofs. The Gothic style, with its vaults, flying buttresses, and pointed gothic arches, developed in the 12th century. In the following centuries, builders achieved incredible feats in stone. Thin stone vaults and towering buildings were built using rules learned through trial and error. Failures were common, especially in difficult areas like crossing towers.

The pile driver was invented around 1500.

Achievements

The scale of fortifications and castle building in the Middle Ages was amazing. But the most outstanding buildings were the Gothic cathedrals, with their thin stone vaults and walls of glass. Famous examples include Beauvais Cathedral, Chartres Cathedral, King's College Chapel, and Notre Dame, Paris.

Renaissance: The Architect's Rise

The Renaissance in Italy, the invention of moveable type (printing press), and the Reformation changed construction. The rediscovery of Vitruvius's book had a big impact. In the Middle Ages, the people who built buildings also designed them. Master masons and carpenters learned their skills by doing, using experience and simple rules. Vitruvius, however, described a perfect architect who knew all arts and sciences. Filippo Brunelleschi was one of the first of these new architects. He started as a goldsmith and learned about Roman architecture by studying ruins. He then engineered the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence.

Materials

Major advances in this period were about how materials were processed. Water mills across Western Europe were used to saw timber into planks. Bricks were used more and more. In Italy, brickmakers were organized into guilds. Kilns were usually in rural areas because of fire risk and easy access to wood and clay. Brickmakers were often paid by the brick, which sometimes made them make bricks too small. So, laws were made to set minimum sizes, and towns kept measures to check bricks. More ironwork was used in roof carpentry for straps and tension parts. Iron was fastened with forelock bolts. Screw-threaded bolts (and nuts) could be made but were a lot of work, so they weren't used on large buildings. Roofs were typically made of terracotta tiles. In Italy, they followed Roman styles. In northern Europe, plain tiles were used. Stone, if available, was still the top choice for important buildings.

Design

The idea of an "architect" coming back in the Renaissance completely changed building design. The Renaissance brought back the classical style of architecture. Leon Battista Alberti's book on architecture made the subject important enough for nobles to study. Before, it was just seen as a technical skill for artisans. This change in the status of architecture and architects was key to how design problems were solved. Renaissance architects were often artists (painters or sculptors) who knew a lot about classical design but less about building technology. So, the architect had to provide detailed drawings for the craftsmen. This process of "design" came from the Italian word for drawing. Sometimes the architect got involved in tough technical problems, but the technical side was mostly left to the craftsmen. This new way of designing buildings changed how problems were approached. Medieval craftsmen thought of a technical solution first, but Renaissance architects started with how the final building should look, then figured out how to make it happen. This led to amazing leaps in engineering.

Techniques

The desire to return to classical architecture created challenges for Renaissance builders. They didn't use concrete, so similar vaults and domes had to be built with brick or stone. The greatest technical achievements were in these areas. The first big breakthrough was Brunelleschi's plan for the dome of Florence Cathedral. Brunelleschi found a way to build a huge dome without temporary supports (formwork). He relied on the weight of the bricks and how they were laid, plus the dome's shape, to keep it standing. How he built it is still debated today because you can't take it apart to study without destroying it. The dome has a double skin, connected by ribs, with wooden and stone chains around it to handle outward pressure.

Brunelleschi's dome was finished (up to the base of the lantern) in 1446. Its size was soon surpassed by the dome of St. Peter's, which used flying scaffolding and two stone shells.

Early Modern Era: Science and Industry Begin

17th Century: Science Meets Building

The birth of modern science in the 17th century greatly influenced building. Towards the end of the century, architect-engineers started using experiments to understand building shapes. 17th-century structures relied on experience, rules of thumb, and small models. It wasn't until the 18th century that engineering theory was good enough to calculate the exact sizes of building parts.

Big improvements in glass making happened in the 17th century. The first cast plate glass was made in France. Iron was used more and more in structures. For example, Christopher Wren used iron hangers for floor beams at Hampton Court Palace and iron rods to fix Salisbury Cathedral and strengthen the dome of St Paul's Cathedral. Most buildings had stone ashlar (cut stone) surfaces over rubble cores, held together with lime mortar. People experimented with mixing lime with other materials to make a hydraulic mortar, but it wasn't like Roman concrete yet. In England, France, and the Dutch Republic, cut and shaped brickwork was used for detailed and fancy building fronts. The triangulated roof truss was introduced to England and used by Inigo Jones and Christopher Wren.

Many old tools are no longer used, but the line gauge, plumb-line (for vertical lines), the carpenter's square, the spirit level, and the drafting compass are still used today.

Despite new science, building methods in this period were still largely medieval. The same types of cranes and timber scaffolding used for centuries were still common. Complex pulley systems allowed large loads to be lifted, and long ramps were used to haul materials up tall buildings.

18th Century: Iron and Professional Builders

The 18th century saw many ideas from the late 17th century grow. Architects and engineers became more professional. Experimental science and math became more advanced and were used in buildings. At the same time, the Industrial Revolution began, leading to bigger cities and faster, more frequent construction.

The use of cast and wrought iron brought big changes. Iron columns had been used in Wren's designs and in some early 18th-century London churches, but only for galleries. In the second half of the 18th century, iron became cheaper, allowing for major iron structures. The Iron Bridge at Coalbrookdale (1779) is a famous example. Large factories needed fire-proof buildings, so cast iron was increasingly used for columns and beams to support brick vaults for floors. The Louvre in Paris had an early wrought-iron roof. Steel was used for tools but couldn't be made in large enough amounts for building.

Brick production increased a lot. Many buildings across Europe were made of brick, often covered in lime plaster to look like stone. Brick making itself didn't change much; bricks were still molded by hand and fired in kilns like those used for centuries. Terracotta, like Coade stone, was used as artificial stone in the UK.

Industrial Revolution: Modern Construction Begins

19th Century: Building Science and Mass Production

Construction became seen as separate from design. Ideas from physics, math, chemistry, and thermodynamics were used to create "building science." The different building jobs (architecture, engineering, and construction) became more clearly defined.

The industrial revolution brought new types of transportation like railways, canals, and macadam roads. These needed huge investments. New building tools included steam engines, machine tools, explosives, and optical surveying equipment. The steam engine, combined with the circular saw and machine-cut nails, led to balloon framing (a lighter, faster way to build wooden houses) and the decline of older timber framing.

As steel was mass-produced from the mid-19th century, it was used for I-beams and reinforced concrete (concrete with steel bars inside). Glass panes also became mass-produced, changing from a luxury to an everyday item. Plumbing appeared, giving common access to drinking water and sewage collection.

Building codes, or safety rules, have been used since the 19th century, especially for fire safety.

20th Century: Skyscrapers and Heavy Machinery

With the Second Industrial Revolution in the early 20th century, elevators and cranes made high rise buildings and skyscrapers possible. Meanwhile, heavy equipment and power tools meant fewer workers were needed. Skyscrapers became very popular, and new technologies like prefabrication (building parts in a factory) and computer-aided design (CAD) appeared.

Trade unions were formed to protect construction workers' rights and ensure occupational safety and health. Personal protective equipment like hard hats and earmuffs also became common and are now required on most sites.

Governments used construction projects to boost the economy, especially during the Great Depression (like the New Deal in the US). For economy of scale (saving money by doing things in large amounts), entire neighborhoods, towns, and cities, including roads and pipes, are often planned and built as one big project. These are called megaprojects if they cost over US$1 billion.

21st Century: Green Building and Digital Tools

By the end of the 20th century, ecology (how living things interact with their environment), energy conservation, and sustainable development (meeting today's needs without harming future generations) became important in construction. Building methods now focus on sustainability, and the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification was created to recognize green buildings.

Builders started using ideas from lean manufacturing (making things efficiently with less waste) to create lean construction concepts. New technologies like 3D Printing, drones, robotics, GPS, building information modelling (BIM), and pre-fabrication made construction more efficient. The United States was one of the first to use 3D printing in construction, where huge machines "print" cement layers to form walls. Robots and drones help builders inspect hard-to-reach areas. Modern homes are often built in factories and then put together on site. Computer software can create 3D models of buildings, allowing construction managers to check how easy a building will be to construct before work even starts. This helps reduce costs from changes later on.

The Digital Age also led to new construction methods like fast-track construction, where design and construction happen at the same time to speed things up. Fast-track construction has become very popular in the 21st century.

Studying Construction History

There isn't one official school subject called "construction history," but more and more researchers are studying it. These include structural engineers, archaeologists, architects, and historians. Even though people have studied this topic since the Renaissance, it became less popular in the mid-20th century. In the last thirty years, there's been a huge increase in interest, which is important for preserving old buildings.

Early Writers

The oldest book about historical building techniques is by the Roman writer, Vitruvius, but it wasn't a detailed historical study. Much later, during the Renaissance, Vasari mentioned that Filippo Brunelleschi was interested in Roman building techniques, but his writings on it don't survive. In the 17th century, Rusconi's drawings for his version of Leon Battista Alberti's book clearly showed Roman wall construction. However, most people were interested in understanding ancient building proportions and details, not how they were built. Early archaeological studies and drawings like those by Giovanni Battista Piranesi showed Roman construction, but they weren't always accurate.

19th Century Studies

In the 19th century, teachers started using images of past building techniques in their lessons, and these images appeared more in construction textbooks. However, the biggest advances were made by English and French architects trying to understand and record Gothic buildings. Examples include the works of Robert Willis in England and Viollet-le-Duc in France. But none of these writers suggested that construction history was a new way to study architecture. Auguste Choisy was perhaps the first to seriously try such a study.

Early 20th Century Studies

Some historians believe that modernism, with its focus on new materials, suddenly ended the interest in construction history that had been growing. With concrete and steel frames, architects weren't as interested in traditional building methods, which seemed old-fashioned. So, very little was published between 1920 and 1950. Interest started to revive in archaeology with studies of Roman construction in the 1950s, but it wasn't until the 1980s that construction history began to be seen as its own field.

Late 20th Century

By the end of the 20th century, even steel and concrete construction became subjects of historical study. The Construction History Society was formed in the UK in 1982. It publishes the only academic international journal on the subject, Construction History, twice a year. The International Congress on Construction History is held every three years, starting in Madrid in 2003.

See also

- History of architecture

- History of structural engineering

- History of water supply and sanitation

- Construction History Society

- Timeline of architecture

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |