Lumières facts for kids

The Lumières (which means The Lights in English) was an important movement of ideas, culture, and thinking that started in the late 1600s in western Europe. It then spread across the rest of Europe. Famous thinkers like Baruch Spinoza, David Hume, John Locke, Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Denis Diderot, and Isaac Newton were part of it. This movement was greatly influenced by the scientific revolution that began in southern Europe, especially from the Italian Renaissance. Over time, the Lumières movement became known as the Age of Enlightenment.

People in this movement saw themselves as advanced thinkers. They fought against unfair religious and political treatment. They also challenged ideas they saw as illogical, unfair, or based on superstition from earlier times. They changed how people studied knowledge to fit the new ideas and styles of their era. Their ideas had a huge impact in the late 1700s, influencing the American Declaration of Independence and the French Revolution.

The Lumières movement mostly focused on Europe and built upon ideas from Renaissance humanism. In Europe, these ideas were well understood. However, outside of France, "enlightenment" usually meant light coming from an outside source. In France, it meant light coming from within a person's own mind.

Generally, in science and philosophy, the Enlightenment aimed for reason to win over faith and belief. In politics and economics, it aimed for the middle class to gain power over the nobility and clergy.

New Ideas and Discoveries

Science Changes How We Think

Big Steps in Science

The Lumières movement really grew from discoveries made earlier. One key discovery was by Nicolaus Copernicus in the 1500s, though his ideas weren't widely known then. The theories of Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) were also very important. People continued to search for clear rules and mathematical proofs, following ideas like those of René Descartes throughout the 1600s.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) and Isaac Newton (1642–1727) both developed calculus around the same time, but independently. Descartes (1596–1650) also introduced the idea of monads. British thinkers like Thomas Hobbes and David Hume used an approach called empiricism. This meant they preferred using their senses and experience to learn, rather than just pure thinking.

Baruch Spinoza agreed with Descartes on many points, especially in his book Ethics. However, in another work, he argued that understanding isn't just about pure reason. It also involves our senses and intuition. Spinoza believed that God and Nature were the same. This idea became very important during the Age of Enlightenment, influencing thinkers from Newton's time to Thomas Jefferson's (1743–1826).

A big change was the rise of naturalist philosophy across Europe, led by Newton. The scientific method proved incredibly useful. This method involves doing experiments and building theories from what you observe. Newton's famous book, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687), showed how powerful this method was. He used observations of planets by Johannes Kepler to confirm his law of universal gravitation. Newton's work showed how to take facts and create a theory that explains them. Naturalism combined the experimental approach of Francis Bacon with Descartes' focus on pure reason.

People started to believe in a world ordered by a Christian God, which became central to how they studied knowledge. Some religious thinkers focused on piety and God's mysterious nature. Others, like deists, believed the world could be understood by human reason and was governed by universal physical laws. They imagined God as a "Great Watchmaker" who set the universe in motion. Scientists found the world to be more and more orderly as their tools became better.

The most famous French naturalist of the 1700s, Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, questioned these religious ideas in his book Histoire Naturelle. Buffon rejected the idea of explaining things with divine intervention when science could now explain them. This led to conflicts with the Sorbonne, which was controlled by the Roman Catholic Church. They tried to censor him. In 1751, he was told to change some of his ideas that went against Church teachings. For example, he suggested the age of the Earth was 74,000 years old, which was very different from the Bible's estimate of around 6,000 years. The Church also disliked Carl Linnaeus. Some people concluded that the Church simply didn't want to believe that nature had its own order.

Freedom and Agreements in Society

This search for universal laws and how things work also helped create the idea of individualism. This meant that every person had rights based only on fundamental human rights. The idea of a thinking individual emerged – someone who could make decisions based on pure reason, not just old customs. In his book Two Treatises of Government, John Locke argued that property rights are personal, not shared. He said they become fair through the work put into getting the property and by others recognizing it. Once the idea of natural law was accepted, it became possible to form modern ideas about what we now call political economy.

In his famous essay, "Answering the Question: What is Enlightenment?", Immanuel Kant described the Lumières movement like this:

Enlightenment is when people become free from being controlled by others. This control happens when they can't use their own understanding without someone else guiding them. People are responsible for this control if it's not because they lack understanding, but because they lack the courage to use their own minds without guidance. Sapere aude! (Dare to know!) Have the courage to use your own understanding! This is the motto of the Lumières.

So, the Lumières' philosophy was based on the idea of a world that is orderly and understandable. This meant that people should also think in an orderly way. Besides physical laws, this included ideas about laws for human affairs. It challenged the idea of the divine right of kings, suggesting that rulers should govern with the people's agreement, not just because they were born into power. This idea influenced Jean-Jacques Rousseau's theory of the social contract. This contract was a relationship between people, families, and groups that would grow stronger. It also included the idea of individual rights that cannot be taken away. For atheist Lumières, the powers of God were not a concern.

The Lumières movement redefined ideas like liberty, property, and rationalism. These words took on meanings that we still use today. They introduced the idea of the free individual into political thinking. They believed the State should guarantee freedom for everyone, not just based on the government's wishes, but backed by a strong rule of law.

To understand the Age of Reason and the Lumières, you can compare Thomas Hobbes with John Locke. Hobbes, who lived in the 1600s, tried to understand human emotions and bring order to a chaotic world. Locke, on the other hand, saw nature as a source of unity and universal rights, with the State protecting those rights. This "culture revolution" in the 1600s and 1700s was a struggle between these two ways of seeing the relationship between people and nature.

In France, this led to the spread of human rights ideas. These ideas were written down in the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. This declaration greatly influenced similar rights declarations in later centuries and caused big political changes worldwide. Especially in France and the United States, freedom of expression, freedom of religion, and freedom of thought were considered basic rights.

Social Ideas and Goals

People's Representation

The main values supported by the Lumières were religious tolerance, liberty, and social equality. In England, America, and France, applying these values led to new definitions of natural law and a separation of political power. People also developed a love for nature and a strong belief in reason.

Today we get three different, often conflicting, educations: from our fathers, from our teachers, and from the world. What the world tells us often overturns the ideas from the first two.

What Philosophers Wanted

The ideal person of the Lumières was a philosopher or a man of letters. This person had a social role: to use their reason in all areas to guide their own thoughts and others'. They would promote a value system and use it to discuss the problems of their time. They were committed individuals involved in society, someone who "approaches everything with reason" (from the Encyclopédie). Denis Diderot described them as someone "who concerns himself with revealing error."

The Lumières' focus on reason did not mean they ignored art and beauty. Reason and sentiment went together in their philosophy. Their thoughts could be both intellectually strict and emotional.

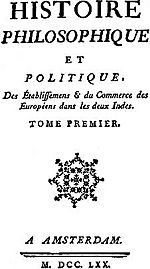

Many Lumières criticized slavery or colonialism, or both. This included Montesquieu in De l'Esprit des Lois (though he still owned a personal slave), Denis Diderot in Supplément au voyage de Bougainville, Voltaire in Candide, and Guillaume-Thomas Raynal in his huge book Histoire des deux Indes. This book was a key example of fighting colonialism in the 1700s, with contributions from Diderot and Baron d'Holbach. It was said, without proof, that Voltaire had invested in the slave trade.

Creating Encyclopedias

At this time, there was a special interest in collecting "all knowledge." This idea was perfectly shown in Diderot and d'Alembert's Encyclopédie. Its full name was "Encyclopaedia, or Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts." Published between 1750 and 1770, it aimed to help people escape ignorance by sharing knowledge as widely as possible.

Challenges and Criticisms

The Lumières movement always faced challenges from two opposing sides. On one side, there was strong spiritualism and traditional religious faith. On the other, an anticlerical movement grew, especially in France. This movement criticized the differences between what religious theory said and what religious practice did.

Anti-clericalism wasn't the only problem in France. Some nobles challenged the king's power, and the upper classes wanted more benefits from their work. A loosening of morals also turned opinion against absolute rule and the old ways.

The French legal system was seen as outdated. Even though business laws had been written down in the 1600s, there was no single, clear civil law.

Voltaire's Views

This social and legal situation was criticized by thinkers like Voltaire. He lived in England from 1726 to 1729, where he studied the works of John Locke and Isaac Newton, and the English monarchy. He became famous for speaking out against injustices, such as those against Jean Calas and François-Jean de la Barre.

The Lumières philosophy reached its peak in the mid-1700s.

For Voltaire, it was clear that if a ruler could make people believe unreasonable things, they could also make them do unreasonable things. This idea became the basis for his criticism of the Lumières. It also led to the start of romanticism, which argued that ideas based purely on reason could create as many problems as they solved.

According to the Lumières philosophers, intellectual progress meant combining knowledge, guided by human reason, with creating a strong moral authority. A different view developed, arguing that such a process would be too influenced by social rules. This would lead to a "New Truth" based on reason that was just a poor copy of the ideal, perfect truth.

The Lumières movement tried to find a balance between "natural" freedom (or independence) and freedom from that liberty. This meant recognizing that natural independence sometimes clashed with the discipline needed for pure reason. At the same time, various rulers tried to slowly redefine society's order and the relationship between the ruler and the people. The idea of a natural order was also common in science, for example, in the works of biologist Carl Linnaeus.

Kant's Ideas

In Germany, Immanuel Kant (who, like Rousseau, considered himself part of the Lumières) strongly criticized the limits of pure reason in his book Critique of Pure Reason. He also criticized English empiricism in Critique of Practical Reason. Compared to Descartes' more personal ideas about metaphysics, Kant developed a more objective view in this area of philosophy.

Adam Smith's Influence

Important thinkers at the end of the Lumières movement, like Adam Smith, Thomas Jefferson, and even the young Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, included ideas of self-organizing and evolving forces in their philosophy. The Lumières believed in a universal truth: that goodness is basic in nature, but it's not always obvious. Instead, human reason helps us discover this constant structure. Romanticism is the exact opposite of this idea.

Art and Design

Generally, the feeling of the Lumières led to a moral sentimentality: after Voltaire's satirical time, people wanted to feel pity, with Rousseau (Julie, or the New Heloise, 1761) and the paintings of Jean-Baptiste Greuze, seeking eternal beauty and goodness. As the century progressed, more literature and art rejected fancy, light forms, which were seen as aristocratic and worldly. They moved towards seriousness, authenticity, and naturalness, which fit the practical morality of the middle-class public. This led to a growing taste for neoclassicism, which highlighted ancient styles, not the symbolic ancient art of the classical era, but a more realistic, simple ancient style, like in the works of the painter Jacques-Louis David.

This led to new ideas about urbanism (city planning). The Lumières' ideal town would be a joint effort between public services and thoughtful architects. They would create administrative or useful buildings (like town halls, hospitals, theaters) with nice views, squares, fountains, and walking paths. The French Académie royale d'architecture believed that "the beautiful is what pleases." But for Abbé Laugier, beauty was what matched reason. He thought the natural model for all architecture was a simple log cabin with four tree trunks, four horizontal parts, and a roof. This model was then used for the Greek temple style, influencing both decoration and structure. This led to a change in style in the mid-1700s: Rococo was rejected, and Ancient Greece and Palladian architecture became the main inspirations for neoclassical architecture.

The University of Virginia, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, was founded by Thomas Jefferson. He designed parts of the campus based on the values of the Lumières.

The Place Stanislas in Nancy, France, is a central point for many neoclassical city buildings. It has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1983, along with other sites in the town like the Place de la Carrière and the Place d’Alliance, which was the administrative center at the time.

Claude Nicolas Ledoux (1736–1806), a member of the Académie d'Architecture, was an architect whose projects best showed the idea of a perfect, purely rational environment. Starting in 1775, he built the Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans, which was a very industrial city in Doubs.

The middle class didn't fully grasp the Lumières' ideas, even though they saw Rousseau, Montesquieu, and Kant as honest men who approved of an "elite." This was a vague idea that many Lumières disagreed with.

There was a lot of discussion in the English and French press, but less in Germany and Italy. In Spain and Russia, only a few intellectuals, officials, and wealthy families knew about the movement. Most common people, even in France, had never heard of Voltaire or Rousseau.

However, the Lumières had shaken up old certainties. This didn't just lead to social and political changes. The Enlightenment inspired a generation of revolutionaries, though it doesn't mean they directly caused the French Revolution of 1789.

Important People and How Ideas Spread

Key Thinkers

Backgrounds of Philosophers

Like Renaissance humanists, the philosophers of the Lumières movement had many different skills. Thomas Jefferson studied law but was also good at archaeology and architecture. Benjamin Franklin was a diplomat and a physicist. Condorcet wrote about many topics, including business, money, education, and science.

These philosophers came from different social backgrounds. Many were from middle-class families (Voltaire, Jefferson). Others came from more humble beginnings (Immanuel Kant, Franklin, Diderot), or from noble families (Montesquieu, Condorcet). Some had religious training (Diderot) or studied law (Montesquieu, Jefferson).

The philosophers formed networks and wrote many letters to each other. The strong disagreements between Rousseau and Voltaire in their letters are well known. These important figures of the 1700s met and debated in literary salons, cafés, or academies. These thinkers and scholars formed an international community. Franklin, Jefferson, Adam Smith, David Hume, and Ferdinando Galiani all spent many years in France.

Because they criticized the established system, the philosophers were often pursued by authorities. They had to use tricks to avoid prison. François-Marie Arouet used the fake name Voltaire. In 1774, Thomas Jefferson wrote a report for the Virginia delegates to the First Continental Congress, which discussed the complaints of Britain's American colonies. Because of its content, he had to publish it anonymously. Diderot's "Letter on the Blind for the Use of those who can See" landed him in prison at the Château de Vincennes. Voltaire was accused of writing pamphlets criticizing Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, and was imprisoned in the Bastille. In 1721, Montesquieu published "Persian Letters" anonymously in Holland. From 1728 to 1734, he traveled to many European countries.

Facing censorship and money problems, philosophers often sought protection from rich aristocrats and supporters. Chrétien Guillaume de Lamoignon de Malesherbes and Madame de Pompadour, the main mistress of King Louis XV, supported Diderot. Marie-Thérèse Rodet Geoffrin (1699–1777) helped pay for the publishing costs of the Encyclopédie. From 1749 to 1777, she hosted a salon every two weeks, inviting artists, intellectuals, writers, and philosophers. Another important salon of the time was run by Claudine Guérin de Tencin. In the 1720s, Voltaire went into exile in England, where he learned about Locke's ideas.

In general, philosophers were less against the king's rule than they were against the power of the clergy and nobility. In his defense of Jean Calas, Voltaire defended the king's justice against the unfairness of local courts. Many European monarchs – Charles III of Spain, Maria Theresa of Austria, Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor, Catherine II of Russia, Gustave III of Sweden – met with philosophers. Voltaire was presented to the Court of Frederick the Great, and Diderot was presented to the Court of Catherine the Great. Philosophers like d'Holbach supported "enlightened absolutism" hoping their ideas would spread faster if the head of state approved them. Later events showed these philosophers the limits of this approach with rulers who were "more absolute than enlightened." Only Rousseau firmly stuck to the revolutionary idea of political equality.

Famous Members

France

- Pierre Bayle, Émilie du Châtelet, Nicolas de Condorcet, Denis Diderot, Jean le Rond d'Alembert, Olympe de Gouges, Baron d'Holbach, Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle, Claude Adrien Helvétius, Louis de Jaucourt, Montesquieu, Voltaire, Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon

World

- England: John Locke, Edward Gibbon, William Godwin, David Hume, Adam Smith, Mary Wollstonecraft

- Germany (Prussia): Immanuel Kant, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Moses Mendelssohn

- Italy: Cesare Beccaria, Ferdinando Galiani, Giambattista Vico

- Poland: Hugo Kołłątaj, Ignacy Krasicki

- Portugal: Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, 1st Marquis of Pombal, Luís António Verney

- Russia: Nikolay Novikov, Mikhail Lomonosov

- Scotland: David Hume, Adam Smith, James Watt

- Spain: Pedro Rodríguez de Campomanes, Benito Jerónimo Feijóo y Montenegro, Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos

- Switzerland (Geneva): Jean-Jacques Rousseau

- United States: John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Thomas Paine, George Washington

Spreading the Word

More people learning to read and write helped create a "public space" for ideas. Intellectual and political debates were no longer just for leaders and the wealthy. They now included more parts of society. New ways of communicating helped these ideas spread even faster. Parts of the Encyclopédie were read in literary salons by nobles and the upper class, who then shared their opinions on the philosophers' writings. Newspapers and postal services allowed ideas to travel quickly across Europe, creating a new sense of shared culture.

Encyclopedists

Another important change from the Lumières movement, especially in France, came from the Encyclopédistes. This group of thinkers believed there was a clear structure to scientific and moral knowledge. They thought this knowledge was natural and that expressing it was a form of human freedom. Starting in 1751, Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert published the Encyclopédie ("Systematic Encyclopaedia or Dictionary of Science, Arts and Crafts"). This raised questions about who should have the liberty to access such information. The Press played a big role in spreading ideas during the French Revolution.

Salons and Cafés

At first, literary cafés like the Café Procope in Paris were popular spots for young poets and critics at night. They could read, debate, and boast about their latest successes in theater or bookstores. But these were soon overshadowed by literary salons, which were open to anyone with talent, especially in public speaking. What made them special was their mix of intellectuals. Men would gather to share their views, learn more, and shape their understanding of the world. However, you had to be "introduced" to these salons. Wealthy women hosted these gatherings, welcoming artists, thinkers, and philosophers. Each hostess had her special day, topic, and guests. A great example is the home of Madame de Lambert around the turn of the century.

Talented men regularly visited these salons to explain their ideas and test their latest works on a special audience. The worldly and cultured women who hosted these salons made the evenings lively. They encouraged shy people and stopped arguments. These women often had strong, independent personalities and were writers or diarists themselves.

This social mixing was especially common in 18th-century France, in what was called the "General States of Human Spirit," where the Lumières philosophy thrived. Some educated women were treated as equals to men on topics of religion, politics, and science. They could also bring a certain style to debates, like Anne Dacier's contributions to the "Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns," and the works of Émilie du Châtelet.

Academies, Libraries, and Clubs

The Academies were learned societies created to collect and share works of literature and science. In France, several Royal institutions were set up in the 1600s, like the Académie française (1634) and the Académie royale des sciences (1666). Other societies were formed in Paris, such as the Académie nationale de médecine in 1731. Most members were clergy and, to a lesser extent, nobility.

Societies in the provinces (outside Paris) helped connect the intellectual elite of French towns. Their members included fewer privileged men than in Paris: 37% were nobility, 20% from the Church, and commoners made up the other 43%. Merchants and manufacturers were a small group (4%).

Nearby academies, public libraries, and lecture halls grew, often involving the same enthusiastic scholars. They were often supported by wealthy individuals or funded by public donations. They collected scientific works and large dictionaries, and had lecture halls and discussion rooms nearby.

All learned societies worked like open salons. They formed networks across provinces, nations, and Europe, exchanging books and letters, welcoming visiting members, and starting research and teaching programs in subjects like physics, chemistry, mineralogy, and demography.

In the British Thirteen Colonies of North America, James Bowdoin (1726–1790), John Adams (1735–1826), and John Hancock (1737–1793) founded the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in Boston during the American Revolutionary War. In 1743, Benjamin Franklin founded the American Philosophical Society. By the early 1800s, Thomas Jefferson had one of the largest private libraries in the country.

Among all learned societies, the most advanced were the Freemasons, though they were limited to the upper classes. Originating in Great Britain, freemasonry embraced all the characteristics of the Lumières: religious, tolerant, liberal, humanist, and artistic. It spread rapidly across Europe, with thousands of lodges by 1789. It became especially successful in becoming part of the government. Masonic lodges were not anti-clerical (which they became in the 1800s) or revolutionary. They helped spread philosophical ideas and the spirit of reform in their political plans. Intellectual discussions sometimes became secret or exclusive. Masonic lodges, even more than the Academies, stressed that equality should be based on ability, not birth.

Traveling Sellers and Printers

The spread of Lumières ideas also relied heavily on traveling traders. As they moved from town to town, they carried ideas and news with them. They could spread this information by word of mouth to people who could not read.

The Press helped spread philosophical writings (especially Diderot and d'Álembert's Encyclopédie). It also encouraged people to think more deeply. In the end, the Press helped shape public opinion, even with constant censorship. Periodicals included the Journal des savants, the Mercure de France, and economic journals like the Éphémérides du citoyen. By cataloging books and with subscriptions to learned societies, people far from political centers could keep up with new ideas, discoveries, and debates every month, or even every day.

Political Impact

By the late 1600s, John Locke had defined the separation of powers in government, dividing it into the executive branch and legislative branch. In his book De l'esprit des lois (1748), Montesquieu brought back the idea of separating powers and added a third: the judicial branch.

In the 1750s, attempts were made in England, Austria, Prussia, and France to make their rulers and laws more "rational."

The "enlightened" idea of a "rational" government was included in the United States Declaration of Independence and, to a lesser extent, in the ideas of Jacobinism during the French Revolution. It then spread to the Constitution of the United States of 1787.

American Revolution's Roots

Thomas Jefferson, a well-educated and knowledgeable man from the State of Virginia, knew the English philosopher John Locke and the Genevan Jean-Jacques Rousseau well. He led the writing of the Constitution of Virginia in 1776. He used parts of it when he drafted the United States Declaration of Independence, which was announced on July 4, 1776, at the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia. In the summer of 1784, he traveled to Europe to take over from Benjamin Franklin as the United States Ambassador to France. During this time, he met many Lumières thinkers and often visited literary salons and bookstores in Paris.

The influence of the Lumières' philosophy is clear in the Declaration of Independence. It states that all men are created equal and opposes tyranny. The 1787 Constitution of the United States repeats Montesquieu's principle of the separation of powers into legislative, executive, and judicial branches. These three branches form the basis of modern democracy.

French Revolution's Connection

As philosophical ideas took hold in salons, cafés, and clubs, the absolute rule of the monarch began to break down. This was partly due to opposition from the French nobility, who saw no future for themselves in reform.

During the French Revolution, philosophical ideas shaped political debates. Most of the representatives in the National Assembly were from the educated middle class. They strongly believed in ideas of liberty and equality. For example, Maximilien de Robespierre was a big follower of Rousseau. But most French philosophers died before seeing their ideas fully bloom during the Revolution. Exceptions included Nicolas de Condorcet, Louis Sébastien Mercier, and Abbé Raynal. The first two of these three Girondists lost favor. Only the third was honored, even after his death in 1796, with a bust made to celebrate his writings on ending black slavery on February 4, 1794.

The French Revolution, especially during the Reign of Terror under the Jacobins, represents a forceful application of the Lumières' philosophy. Descartes described the desire for a "rational" and "spiritual" revolution as one that aimed to completely remove the Church and Christianity.

The National Convention canceled the French Republican Calendar, the system of measuring time, and the system of currency. At the same time, they made the goal of equality, both social and economic, the highest priority for the State.

Images for kids

-

The Reader (around 1770) by Jean-Honoré Fragonard

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |