History of banking facts for kids

The history of banking is all about how people started lending, borrowing, and keeping money safe. It began a very long time ago, around 2000 BC, in places like Assyria, India, and Sumer. Back then, merchants would lend grain to farmers and traders.

Later, in ancient Greece and the Roman Empire, temples became places where people could get loans, deposit money, and even exchange different types of money. There's also proof of money lending from ancient China and India during these times.

Many experts believe that the modern banking system we know today started in Italy during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Cities like Florence, Venice, and Genoa were very rich and important. Families like the Bardi and Peruzzi in Florence were big bankers in the 1300s, with branches all over Europe. The most famous Italian bank was the Medici Bank, started by Giovanni Medici in 1397. The oldest bank still open today is Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena in Siena, Italy, which has been running since 1472!

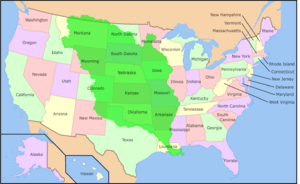

Banking ideas spread from northern Italy to the rest of Europe, especially in the 1400s and 1500s. Important new ideas came from Amsterdam in the 1600s and London in the 1700s. In the 1900s, new technologies like phones and computers changed banking a lot. Banks grew much bigger and spread all over the world. However, the financial crisis of 2007–2008 caused many banks to fail, which led to a lot of talk about how banks should be controlled.

Contents

- Early Ways People Handled Money

- First Steps in Banking Across Asia

- Banking in Ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome

- Religious Rules About Interest

- Banking Grows in Medieval Europe

- Banking Expands: 1400s to 1600s

- Modern Banking Takes Shape: 1600s to 1800s

- Banking in the 20th Century

- Banking in the 21st Century

- Key Moments in Banking History

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Ways People Handled Money

Long ago, people stopped just hunting and gathering food and started farming. This change, which began about 12,000 years ago, made economic life more stable.

Money and Trade in Ancient Times

Some of the earliest forms of money were "grain-money" and "food cattle-money," used around 9000 BCE for bartering (trading goods directly).

People also traded valuable materials. For example, Anatolian obsidian, a type of volcanic glass used for tools, was traded as early as 12,500 BCE. Later, around 3000 BCE, trade shifted to copper and silver.

Keeping Records of Money

People in the Near East used special objects called "bulla" and "tokens" to keep track of farm products. These date back to 8000 BCE. By the late 3000s BCE, temples and palaces used symbols to record their supplies.

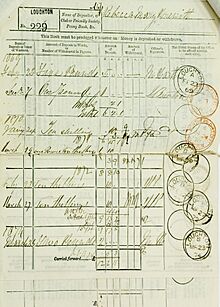

Around 3200 BCE, records for trade payments started appearing. The Code of Hammurabi, a set of laws written on a clay tablet around 1700 BCE, even had rules about banking! This shows that banking was developed enough to need laws. Later, during the Achaemenid Empire (after 646 BCE), we find more proof of banking in Mesopotamia.

First Steps in Banking Across Asia

Early forms of banking, or "quasi-banking," are thought to have started in the late 3000s BCE.

Banking in Mesopotamia and Persia

Before Sargon I of Akkad (2335–2280 BCE), trade was mostly limited to inside each city-state in Babylon. The temple was the center of economic life.

In Babylonia around 2000 BCE, people who deposited gold had to pay a small fee. Palaces and temples also lent out their wealth, usually grain, which was paid back after the harvest. These agreements were written on clay tablets and included rules about interest. People continued to store wealth in temples until at least 209 BCE.

The Code of Hammurabi (around 1792–1750 BCE) had specific laws about banking:

- Law 100 said that loans had to be paid back on a set schedule with a written contract.

- Law 122 said that if you deposited gold, silver, or other items, you needed a signed contract from a notary.

- Law 123 said a banker wasn't responsible if the notary denied the contract.

- Law 124 said a depositor with a notarized contract could get all their deposit back.

- Law 125 said a banker was responsible for replacing deposits stolen while in their care.

Records from the house of Egibi in Babylonia (after 1000 BCE) show a family involved in "professional banking," similar to modern deposit banking.

Temples as Banks in Asia Minor

The temple of Artemis at Ephesus was the biggest storage place for wealth in Asia. A pot of treasure from 600 BCE was found there. Famous people like Aristotle and Caesar used the temple as a safe place for their deposits.

The temple to Apollo in Didyma also held a lot of gold, deposited by King Croesus in the 500s BCE.

Banking in India

In ancient India, there's proof of loans from the Vedic period (starting 1750 BCE). During the Maurya dynasty (321 to 185 BCE), people used something called an adesha. This was an order for a banker to pay money to a third person, much like a modern bill of exchange. These were widely used during the Buddhist period, and merchants gave each other letters of credit.

Banking in China

In ancient China, during the Qin Dynasty (221 to 206 BCE), money developed with standardized coins. This made trade easier and led to the creation of letters of credit. Merchants issued these letters, acting much like banks do today.

Banking in Ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome

Ancient Egypt's Grain Banks

Some experts believe that Egypt's grain-banking system was very advanced, similar to big modern banks. It had many branches and employees, and handled huge amounts of transactions. During the rule of the Greek Ptolemies, grain storage places became a network of banks centered in Alexandria. This was one of the first known government central banks.

Egypt had two types of banks: royal (government) and private. Records called "peptoken-records" showed how taxes were banked.

Greek Banking: Temples and Traders

The first writings about banking come from Greece. Speeches by Demosthenes mention lending money. Xenophon even suggested creating a joint-stock bank around 353 BCE.

After the Persian Wars, Greek city-states became organized enough for private citizens to own wealth, not just the state. This helped banking grow.

Trapezites (ancient Greek bankers) were among the first to trade using money, starting in the 400s BCE. Before that, people mostly traded goods directly.

Temples in ancient Greece, like the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus, the temple of Hera in Samos, and the temple to Apollo in Delphi, acted as financial centers. They held treasure for safe-keeping, exchanged currency, checked coins, and gave loans.

The first treasury for the Apollonian temple was built before the late 600s BCE. Another treasury was built by the city of Siphnos in the 500s BCE.

The Athenian Acropolis temple, dedicated to Athena, stored money before it was destroyed by Persians in 480 BCE. Pericles later rebuilt a storage place in the Parthenon.

By the end of Ptolemy I's rule (305–284 BCE), state storage places replaced temples for security deposits. As banking grew, new buildings for banks were built around city markets (agoras).

Athens received the Delian League's treasury in 454 BCE. Later, the island of Delos became a major banking center in the 200s and 100s BCE. By the 100s BCE, Delos had three private banks and one temple depository.

Many loans are mentioned in old Greek writings, but banks provided only a small number of them. In Athens, loans were sometimes given at 12% annual interest. Banks sometimes kept loans and depositors' names secret.

Roman Banking: From Stalls to Statutes

Roman banking also took place in temples. Coins were minted in temples, especially the Temple of Juno Moneta. However, during the Empire, public deposits slowly moved from temples to private places.

Around 352 BCE, a basic public bank was created to help poor people with debt. Later, in 325 BCE, new officials called quinqueviri mensarii helped common people borrow money from the public treasury if they had something to offer as security. Banking shops in Ancient Rome first opened in public forums between 318 and 310 BCE.

Early Roman deposit bankers were called argentarii, and later nummularii or mensarii. Their banking houses were called Taberae Argentarioe and Mensoe Numularioe. They set up stalls in market courtyards on a long bench called a bancu, which is where the words banco and bank come from. As money changers, they converted foreign money into Roman currency.

Roman banking activities were known as officium argentarii. Laws from 125/126 CE show that rent money from temple lands was collected and given to the temple treasurer. A law called receptum argentarii made banks responsible for paying their clients' guaranteed debts.

Cassius Dio suggested creating a state bank funded by selling all state-owned properties.

In the 300s CE, monopolies existed in Byzantium and Olbia in Sardinia.

The Roman Empire eventually made banking more formal and regulated financial institutions. Charging and paying interest on loans became more developed. However, Romans preferred cash, which limited bank growth. During Emperor Gallienus's rule (260–268 CE), the banking system temporarily broke down when banks refused his copper coins. With the rise of Christianity, charging interest was seen as wrong, which added more rules. After the fall of Rome, banking in Europe likely stopped for a while and didn't restart until trade in the Mediterranean began again in the 1100s.

Religious Rules About Interest

Most early religions and laws in the ancient Near East did not forbid charging usury (interest). They thought that inanimate things, like plants or money, could "reproduce." So, if you lent "food money" (like olives or seeds), it was okay to charge interest. In places like Mesopotamia, Hittites, Phoenicians, and Egyptians, interest was legal and often set by the state.

Judaism and Loans

The Torah and other parts of the Hebrew Bible criticize taking interest. One common idea is that Jews should not charge interest to other Jews, but they could charge interest to non-Jews. However, the Bible itself shows many times when this rule was avoided.

Deuteronomy 23:19 says: "You shall not lend upon interest to your brother: interest of money, interest of victuals, interest of any thing that is lent upon interest." Deuteronomy 23:20 says: "Unto a foreigner you may lend upon interest; but unto your brother you shall not lend upon interest; that the LORD your God may bless you in all that you put your hand unto, in the land whither you go in to possess it."

It was generally seen as good to avoid debt, so you wouldn't be tied to someone else. Debt was not for buying things you didn't need, unless you were truly in need. However, prophets often criticized people for breaking laws against usury.

In the 1300s, Jews living in Christian Europe used the idea that interest could be charged to non-Israelites to justify lending money for profit. This helped them get around the rules against usury in both Judaism and Christianity.

Christianity and Usury

Originally, Christian churches banned charging interest, calling it usury. This included charging a fee for exchanging money. Over time, charging interest became more accepted as money changed. The term 'usury' then came to mean charging interest above what was allowed by law.

Despite the ban on usury, some banking activities happened. The Knights Templar (1100s), Mounts of Piety (1462), and the Apostolic Chamber (connected to the Vatican) all engaged in money loans, guarantees, and investments.

The rise of Protestantism in the 1500s lessened Rome's power, and its rules against usury became less important in some areas. This helped banking grow in Northern Europe. In the late 1700s, Protestant merchant families became more involved in banking, especially in trading countries like the United Kingdom (Barings), Germany (Schroders, Berenbergs), and the Netherlands (Hope & Co., Gülcher & Mulder). New financial activities also expanded banking far beyond its original purpose. Some believe that Calvinism helped set the stage for capitalism in Northern Europe by challenging the old views on usury and profit.

Islam and Interest (Riba)

The Quran strictly forbids lending money on interest, known as Riba. "Believers! Have fear of Allah and give up all outstanding interest if you do truly believe. But if you fail to do so then be warned of war from Allah and His Messenger. If you repent even now you have the right of the return of your capital; neither will you do wrong nor will you be wronged." (2:278-279) "O you who have believed, do not consume usury, doubled and multiplied, but fear Allah that you may be successful" (3:130) "and Allah has permitted trade and has forbidden interest" (2:275).

The Quran says that taking interest was forbidden for Muslims and other communities in earlier times too.

Islamic legal experts talk about two types of riba:

- An increase in capital without providing services (forbidden by the Qur'an).

- Unequal exchanges of goods (forbidden by the Sunnah).

Trading in promissory notes (like paper money) is also forbidden.

Despite the ban on interest, in the 1900s, Islamic banking models developed. These banks don't charge interest but still make a profit. They do this by charging fees, sharing risks, and using different ownership models like leasing.

Banking Grows in Medieval Europe

Modern banking started in medieval and early Renaissance Europe. The Lombards in Italy (1100s-1200s) and the Cahorsins in France (1200s) were important. But the rich Italian cities like Florence, Venice, and Genoa were especially key.

The Rise of Merchant Banks

The first banks were "merchant banks," created by Italian grain merchants in the Middle Ages. As merchants and bankers in Lombardy grew wealthy from cereal crops, many Jews fleeing Spanish persecution joined the trade. They brought old methods from the Middle and Far East, which had been used to finance the silk routes. They used these methods to finance grain production and distribution.

Since Jews couldn't own land in Italy, they set up their "benches" in the big trading markets of Lombardy. They had an advantage: Christians were strictly forbidden from usury (lending at interest), and this was also condemned in the Islamic world. But Jewish traders could make high-risk loans to farmers against future crops without direct church rules. They also started paying for grain before it was shipped to distant ports, making a profit from the difference in price.

These traders did both financing (giving credit) and underwriting (insurance). They gave crop loans at the start of the season to help farmers grow their crops. They also insured the delivery of crops to buyers. If a crop failed, they could supply the buyer from other sources or help the farmer stay in business.

Merchant banking grew from financing one's own trade to settling trades for others. Then, they started holding deposits for "billette" (notes) written by grain brokers. So, the merchant's "benches" (bank comes from the Italian banca, meaning bench) in the grain markets became places to hold money against a bill (a note or letter of exchange, later a cheque).

These deposited funds were meant for grain trades, but bankers often used them for their own trades in the meantime. The word bankrupt comes from the Italian banca rotta, meaning "broken bench," which symbolized a trader who couldn't pay his debts.

Banking and the Crusades

In the 1100s, a lot of money was needed to pay for the Crusades. This helped banking reappear in western Europe. In 1162, Henry II of England started taxing people to support the crusades. The Templar and Hospitaller knights acted as Henry's bankers in the Holy Land.

A decree by Pope Innocent II helped the Templars succeed. It allowed them to collect tithes (church taxes) for their own profit and freed them from paying tithes to the church. The Templars' rich land holdings across Europe became the start of Europe-wide banking between 1100 and 1300. They took in local money and gave out notes that could be cashed at any of their castles across Europe. This allowed people to move money without the risk of robbery.

How Interest Was Handled

To get around the religious rule against usury (charging money for using money), the idea of discounting developed. In theory, this gave depositors a share in the profits from trades made with their money. Similar methods had been used in Islamic banking for a long time.

Medieval trade fairs, like the one in Hamburg, also helped banking grow. Money changers gave out documents that could be cashed at other fairs, in exchange for real money. These documents could be redeemed later, often at a slightly lower price, which was like paying interest. Eventually, these documents became bills of exchange, which could be cashed at any office of the issuing banker. This made it possible to transfer large sums of money without carrying heavy chests of gold.

Famous Italian Bankers

The Republic of Venice is sometimes wrongly credited with starting a bank in the 1100s. But it didn't formally create a public bank until 1587. However, in the 1200s and 1300s, its Grain Office did banking business, taking deposits and lending money. Venice's system of transferable public debt also helped banking develop.

In the mid-1200s, Christian groups, especially the Italian Lombards and French Cahorsins, found legal ways around the ban on Christian usury. For example, they might offer a loan without interest, but require insurance against loss or delays in repayment. These Christians became known as the "pope's usurers" and reduced the importance of Jewish money-lenders to European kings. Later in the Middle Ages, it became okay to charge interest on loans for durable goods, but not for necessities like food.

The most powerful banking families came from Florence, including the Acciaiuoli, Mozzi, Bardi, and Peruzzi families. They set up branches all over Europe. The most famous was the Medici bank, started by Giovanni di Bicci de' Medici in 1397 and running until 1494. The oldest banking firm still operating today is Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena S.p.A. (BMPS).

By the later Middle Ages, Christian merchants who lent money with interest gained church approval, and Jews lost their special role as money-lenders. Italian bankers took their place. By 1327, Avignon had 43 branches of Italian banking houses. In 1347, Edward III of England failed to pay back his loans. This led to the bankruptcy of the Bardi (1343) and Peruzzi (1346) banks. Italian banking also grew in France, with Lombard moneychangers moving between cities along busy trade routes. Key cities were Cahors and Figeac.

After 1400, politics turned against Italian bankers. In 1401, King Martin I of Aragon expelled some of them. In 1403, Henry IV of England stopped them from making profits in his kingdom. In 1409, Flanders imprisoned and then expelled Genoese bankers. In 1410, all Italian merchants were expelled from Paris. In 1407, the Bank of Saint George, the first state bank for deposits, was founded in Genoa and became very important in the Mediterranean.

Banking Expands: 1400s to 1600s

Italian Banking Families

Between 1527 and 1572, important banking families emerged from the Genoese Republic in northern Italy. These included the Grimaldi, Spinola, and Pallavicino families, who were very powerful and rich. The Doria, Pinelli, and Lomellini families were also important.

Spain and the Ottoman Empire

In 1401, the leaders of Barcelona, then the capital of Principality of Catalonia, created the Taula de canvi de Barcelona or Table of Exchange. This was the first public bank in Europe, based on the Venetian model.

Some historians suggest that in the 1500s, Marrano Jews (like Doña Gracia from the House of Mendes) who fled from Spain brought European banking techniques and ideas about state economy to the Ottoman Empire. In the 1500s, the main financiers in Istanbul were Greeks and Jews. Many Jewish financiers were Marranos who had fled Spain. Some of these families brought great wealth with them.

The most famous Jewish banking family in the 1500s Ottoman Empire was the Marrano Mendes family. They moved to Istanbul in 1552, protected by Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. When Alvaro Mendes arrived in Istanbul in 1588, he reportedly brought 85,000 gold ducats. The Mendes family soon became very powerful in the Ottoman Empire's finances and trade with Europe.

Jewish bankers also thrived in Baghdad during the 1700s and 1800s under Ottoman rule. They performed important commercial tasks like moneylending and banking. Like the Armenians, Jews could do these necessary business activities that were often forbidden for Muslims under Islamic law.

Court Jews

Court Jews were Jewish bankers or businessmen who lent money and managed the finances of some Christian European noble families, mostly in the 1600s and 1700s. They were like early financiers or treasury secretaries. Their jobs included collecting taxes, arranging loans, managing the mint, finding new ways to make money, issuing bonds, creating new taxes, and supplying the military. They also acted as personal bankers for the nobility, raising money for their diplomacy and lavish spending.

Court Jews were skilled managers and businessmen who received special rights for their services. They were most common in Germany, Holland, and Austria, but also in other European countries. Almost every duchy, principality, and palatinate in the Holy Roman Empire had a court Jew.

German Banking Families

In southern Germany, two big banking families appeared in the 1400s: the Fuggers and the Welsers. They controlled much of the European economy and dominated international finance in the 1500s. The Fuggers built the first German social housing area for the poor in Augsburg, called the Fuggerei. It still exists, but the original Fugger Bank (1487-1657) does not.

Dutch bankers helped establish banking in the northern German city-states. Berenberg Bank is the oldest bank in Germany and the world's second oldest. It was started in 1590 by Dutch brothers Hans and Paul Berenberg in Hamburg. The bank is still owned by the Berenberg family.

Dutch Banking Innovations

In the 1500s and 1600s, precious metals from the New World, Gold Coast, Japan, and other places came into Europe, causing prices to rise. Thanks to free coinage, the Bank of Amsterdam, and increased trade, the Netherlands attracted even more coins and gold to be deposited in their banks. The ideas of fractional-reserve banking (where banks lend out most of the money deposited) and payment systems were further developed and spread to England and other places.

Early Banking in England

In the City of London, there were no banking houses like we know them today until the 1600s, although the London Royal Exchange was set up in 1565.

Modern Banking Takes Shape: 1600s to 1800s

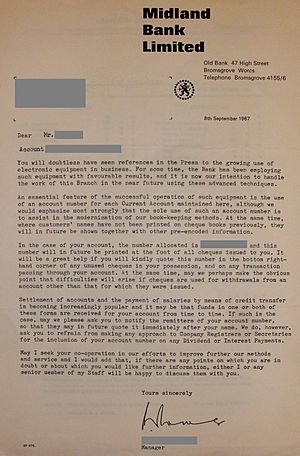

By the late 1500s and during the 1600s, the traditional banking tasks of taking deposits, moneylending, money changing, and transferring funds were combined with issuing bank debt that acted like gold and silver coins.

New banking practices helped trade and industry grow. They provided a safe way to pay and a money supply that could respond to business needs. They also "discounted" business debt (buying it at a lower price). By the end of the 1600s, banking also became important for governments needing money for wars. This led to government rules and the first central banks. The success of new banking methods in Amsterdam and London helped these ideas spread across Europe.

London's Goldsmiths Become Bankers

Modern banking, including fractional reserve banking and issuing banknotes, started in the 1600s. Rich merchants in London began storing their gold with goldsmiths, who had private vaults and charged a fee. For each deposit, goldsmiths gave receipts showing the amount and purity of the metal. At first, only the original depositor could collect the gold.

Eventually, goldsmiths started lending out the money on behalf of the depositor. This led to modern banking. Promissory notes (which became banknotes) were issued for money deposited as a loan to the goldsmith.

These practices created a new kind of "money"—the goldsmiths' debt, not actual gold or silver coins. This required people to accept the goldsmiths' notes as payment, trusting that real coin would be available. A fractional reserve (keeping only a portion of deposits on hand) usually worked for this. It also required that people holding these notes could legally demand payment. The idea of negotiable instruments (notes that could be easily transferred) developed by the 1600s. However, an Act of Parliament was needed in the early 1700s to make sure goldsmiths' notes were legally negotiable.

The Modern Bank Emerges

In 1695, the Bank of England became one of the first banks to issue banknotes. The first ones were handwritten and promised to pay the bearer the value of the note in gold or silver on demand. By 1745, standard printed notes from £20 to £1,000 were issued. Fully printed notes that didn't need a payee's name or cashier's signature appeared in 1855.

In the 1700s, banks offered more services. They introduced clearing facilities (for settling payments between banks), security investments, cheques, and overdraft protection. Cheques had been used since the 1600s in England, with banks settling payments by sending couriers. Around 1770, banks started meeting in a central place to settle payments, and by the 1800s, a dedicated bankers' clearing house was set up. The first overdraft facility was created in 1728 by the Royal Bank of Scotland.

The number of banks grew during the Industrial Revolution and with increasing international trade, especially in London. New financial activities also expanded banking. Merchant-banking families handled everything from underwriting bonds to arranging foreign loans. These new "merchant banks" helped trade grow, benefiting from England's rising power in sea shipping. Two immigrant families, Rothschild and Baring, started merchant banking firms in London in the late 1700s and became dominant in world banking in the next century.

Country banking got a big boost in 1797 when the Bank of England stopped cash payments due to war threats. Parliament then allowed the Bank of England and country bankers to issue low-value notes.

Chinese Banking Develops

During the Qing dynasty, China's private financial system was first developed by the Shanxi merchants. They created "draft banks." The first one, Rishengchang, started around 1823 in Pingyao. Some large draft banks had branches in Russia, Mongolia, and Japan to help with international trade. For most of the 1800s, the central Shanxi region was the financial hub of Qing China.

When the Qing dynasty fell, financial centers moved to Shanghai, where modern Western-style banks grew. Today, China's financial centers are Hong Kong, Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen.

Japanese Banking Reforms

In 1868, the Meiji government in Japan tried to create a working banking system, following French models. The Imperial mint started using British machines in the early Meiji period.

Masayoshi Matsukata was a key figure in later banking efforts.

The Rise of Central Banks

The Taula de canvi de Barcelona, founded in 1401, was an early example of a public bank that acted like a central bank on a small scale. It was soon copied by the Bank of Saint George in Republic of Genoa (1407), and later by the Banco del Giro in Republic of Venice and banks in Naples. Important municipal central banks were set up in the early 1600s in European trade centers, like the Bank of Amsterdam in 1609 and the Hamburger Bank in 1619. These banks provided a public system for international payments without cash.

The first national central bank was the Swedish central bank, now called Sveriges Riksbank, founded in Stockholm in 1664. Later, the Bank of England was created in 1694 to provide money to the English King. It was the only company allowed to issue banknotes. A major attempt at national central banking failed in France with John Law's Banque Royale in 1720-1721. A more successful one was the Bank of Spain in 1782. The Russian Assignation Bank (1769) was unique because it was directly owned by the government. In the early United States, Alexander Hamilton set up the First Bank of the United States in the 1790s, despite strong opposition.

Many European countries established central banks in the 1800s. Napoleon created the Banque de France in 1800 to stabilize the French economy and fund his wars. The Bank of France remained the most important central bank in mainland Europe throughout the 1800s. The Bank of Finland was founded in 1812. At the same time, powerful family banking networks, like the House of Rothschild and Hottinguer, also played a central banking role.

In the 1800s and early 1900s, central banks in most of Europe and Japan developed under the international gold standard. However, problems with bank collapses during economic downturns led to more support for central banks in countries that didn't have them, like Australia. In the United States, the role of a central bank had ended in the 1830s. But in 1913, the U.S. created the Federal Reserve System.

After World War I, the Economic and Financial Organization of the League of Nations promoted the idea of independent central banks. They helped create new central banks in Austria, Hungary, Danzig, and Greece, and reformed others. By 1935, almost every independent nation had a central bank. After gaining independence, many African and Asian countries also set up central banks. By the early 2000s, most countries had a national central bank, usually a public institution, with varying levels of independence.

The Rothschild Family's Influence

The Rothschild family pioneered international finance in the early 1800s. They lent money to the Bank of England and bought government bonds. Their wealth might have been the largest in modern history. In 1804, Nathan Mayer Rothschild started trading financial instruments like foreign bills and government securities on the London stock exchange. From 1809, he dealt in gold bullion, making it a key part of his business.

From 1811, he arranged to transfer money to pay Wellington's troops fighting Napoleon in Portugal and Spain. Later, he made payments to British allies. His four brothers helped coordinate activities across Europe. The family built a network of agents, shippers, and couriers to transport gold and information. This private intelligence service allowed Nathan to get news of Wellington's victory at the Battle of Waterloo a full day before the government's official messengers.

The Rothschild family was crucial in supporting railway systems worldwide and financing big government projects like the Suez Canal. They bought a large amount of property in Mayfair, London. Major businesses they founded include Alliance Assurance (1824), Chemin de Fer du Nord (1845), Rio Tinto Group (1873), and others. The Rothschilds also financed the founding of De Beers and Cecil Rhodes's expeditions in Africa.

The Japanese government asked the London and Paris Rothschild families for money during the Russo-Japanese War. The London group's Japanese war bonds totaled £11.5 million. From 1919 to 2004, the Rothschilds' Bank in London was where the gold fixing (setting the price of gold) took place.

Napoleon and Paris Banking

Napoleon III wanted Paris to become the world's top financial center, surpassing London. However, the war in 1870 reduced Paris's financial influence. Paris had become a major international financial center in the mid-1800s, second only to London. It had a strong national bank and many active private banks that funded projects across Europe and the growing French Empire.

A key development was the establishment of a main branch of the Rothschild family. In 1812, James Mayer Rothschild came to Paris from Frankfurt and set up the bank "De Rothschild Frères." This bank funded Napoleon's return from Elba and became one of Europe's leading banks. The Rothschild banking family of France funded France's major wars and colonial expansion. The Banque de France, founded in 1796, helped solve the financial crisis of 1848 and became a powerful central bank. The Comptoir National d'Escompte de Paris (CNEP) was created during the 1848 crisis. It used both private and public money for large projects and built a network of local offices to reach more depositors.

Building Societies for Homes

Building societies were financial organizations owned by their members. They started in late-1700s Birmingham, England, a city growing fast with many small metalworking firms. Their skilled and wealthy owners often invested in property.

Many early building societies met in taverns or coffeehouses, which were centers for clubs and groups where people shared ideas. The first building society, Ketley's Building Society, was founded by Richard Ketley, a tavern owner, in 1775.

Members paid a monthly fee into a central fund. This fund was used to build houses for members, and these houses then served as collateral to attract more funding for the society, allowing more construction. The first one outside the English Midlands was in Leeds in 1785.

Mutual Savings Banks and Credit Unions

Mutual savings banks also appeared around this time. These were financial institutions created by the government, owned by their members, who contributed to common funds. The "Savings and Friendly Society," started by Reverend Henry Duncan in 1810 in Ruthwell, Scotland, is often called the first modern savings bank. Rev. Duncan created the bank to encourage his working-class church members to save money.

Another early savings bank idea came from Germany, with Franz Hermann Schulze-Delitzsch and Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen. They developed cooperative banking models that led to the credit union movement. Traditional banks often ignored poor and rural communities because they had little cash and limited resources. The idea of cooperative banking spread through northern Europe and to the US in the early 1900s.

Postal Savings Systems

To give people who didn't have access to banks a safe way to save money, the postal savings system was introduced in Great Britain in 1861. William Ewart Gladstone, then the finance minister, strongly supported it as a cheap way to fund government debt. At the time, banks were mainly in cities and served wealthy customers. People in rural areas and the poor had to keep their money at home. The original Post Office Savings Bank limited deposits to £30 a year, with a maximum balance of £150. Interest was paid at 2.5% per year on whole pounds in the account.

Similar systems were created in other countries in Europe, North America, and Japan. For example, in 1881, the Dutch government created the Rijkspostspaarbank (State post savings bank) to encourage workers to save. Forty years later, they added Postcheque and Girodienst services, allowing families to make payments through post offices.

Banking in the 20th Century

The early 1900s saw the Panic of 1907 in the US, which caused many runs on banks and was known as the bankers' panic.

The Great Depression's Impact

During the Crash of 1929, before the Great Depression, people only needed to put down 10% of the money to buy stocks. Brokerage firms would lend $9 for every $1 an investor had. When the market fell, brokers asked for these loans back, but people couldn't pay. Banks started to fail as people couldn't pay their debts, and depositors rushed to withdraw their money, causing many bank runs. Government guarantees and Federal Reserve rules didn't work or weren't used. Bank failures led to billions of dollars in lost assets. Debts became harder to pay because prices and incomes fell by 20–50%, but the debt amounts stayed the same. After the 1929 panic, 744 US banks failed in the first 10 months of 1930. By April 1933, about $7 billion in deposits were stuck in failed banks.

Bank failures grew worse as desperate bankers demanded loan repayments that borrowers couldn't make. With future profits looking bad, capital investment and construction slowed or stopped. Surviving banks became even more careful about lending. They built up their reserves and made fewer loans, which made prices fall even more. This created a vicious cycle, and the economy worsened. In total, over 9,000 banks failed in the 1930s.

In response, many countries greatly increased financial regulation. The U.S. created the Securities and Exchange Commission in 1933 and passed the Glass–Steagall Act. This law separated investment banking (risky activities) from commercial banking (regular deposits and loans) to prevent investment banking from causing commercial bank failures again.

World Bank and New Payment Technology

After Second World War, the Bretton Woods system was set up in 1944, creating two organizations: the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. Encouraged by these, commercial banks started lending to countries in the developing world. This happened as inflation began to rise in Western countries. The gold standard (where money was backed by gold) was abandoned in 1971. Many banks went bankrupt because developing countries couldn't pay back their debts.

This was also a time when technology was increasingly used in retail banking. In 1959, banks agreed on a standard for machine-readable characters (MICR) for cheques, leading to the first automated reader-sorter machines. In the 1960s, the first automated teller machines (ATMs) or cash machines appeared. Banks started investing heavily in computers to automate many manual tasks, shifting from large clerical staffs to new automated systems. By the 1970s, the first payment systems developed, leading to electronic payment systems for both international and domestic payments. The international SWIFT payment network was created in 1973, and banks and governments worldwide developed domestic payment systems.

Deregulation and Global Banking

Global banking and capital market services grew rapidly in the 1980s after many countries loosened financial rules. The 1986 'Big Bang' in London allowed banks new ways to access capital markets. This greatly changed how banks operated and got money. It also started a trend where retail banks bought investment banks and stock brokers, creating universal banks that offered many banking services. This trend also spread to the US after much of the Glass–Steagall Act was repealed in 1999. US retail banks then began many mergers and acquisitions and also got involved in investment banking.

Financial services continued to grow through the 1980s and 1990s due to high demand from companies, governments, and financial institutions. Also, financial markets were strong. Interest rates in the United States fell from about 15% to about 5% over 20 years, and financial assets grew about twice as fast as the world economy.

This period saw financial markets become much more international. Increased U.S. foreign investments from Japan not only provided money to US companies but also helped fund the federal government.

The dominance of US financial markets was decreasing, and there was growing interest in foreign stocks. The huge growth of foreign financial markets came from large increases in savings in countries like Japan, and especially from loosening financial rules abroad, which allowed them to expand. So, American companies and banks started looking for investment opportunities overseas, leading to the development of mutual funds in the US that specialized in foreign stock markets.

This growing internationalization changed competition. Many banks preferred the "universal banking" model common in Europe. Universal banks can offer all types of financial services, invest in client companies, and act as a "one-stop" provider for both individual and large-scale financial services.

Banking in the 21st Century

The early 2000s saw banks merging and other financial companies entering the market. Large corporations started offering financial services, competing with established banks. These services included insurance, pensions, mutual funds, money market and hedge funds, loans, and securities. By the end of 2001, four of the world's 15 largest financial service providers were not traditional banks.

The first decades of the 21st century saw the peak of banking technology. There was a big shift from traditional banking to internet banking. Starting in 2015, developments like open banking made it easier for other companies to access bank transaction data, introducing standard ways to connect and security models.

Financial innovation also grew hugely in the early 2000s, making non-bank finance more important and profitable. This profitability, once only for non-banking companies, encouraged banks to explore other financial tools. This helped banks diversify their business and improve their financial health. As both banking and non-banking industries use similar financial tools, the difference between them is slowly disappearing. For example, in 2020, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) clarified that national banks could hold cryptocurrency and offer banking services to crypto companies. In 2021, the OCC gave its first federal banking license to Anchorage Digital, a digital asset platform.

The 2007–2008 Financial Crisis

The financial crisis of 2007–2008 put great pressure on banks worldwide. Many major banks failed, leading to government bail-outs. The collapse and sale of Bear Stearns to JPMorgan Chase in March 2008, and the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September that year, caused a credit crunch and global banking crises. In response, governments around the world rescued, nationalized, or arranged quick sales for many major banks. Starting with the Irish government on September 29, 2008, governments provided guarantees to banks to prevent a systemic failure of the entire banking system. These events led to the term 'too big to fail' and much debate about the risks of such actions.

Key Moments in Banking History

- 1100 – Knights Templar run the earliest European-wide/Mideast banking until the 1300s.

- 1397 – The Medici Bank of Florence is established in Italy and operates until 1494.

- 1542 – The Great Debasement, the English Crown's policy of reducing the value of coins during the reigns of Henry VIII and Edward VI.

- 1553 – The first joint-stock company, the Company of Merchant Adventurers to New Lands, is created in London.

- 1602 – The Amsterdam Stock Exchange is established by the Dutch East India Company for trading its stocks and bonds.

- 1609 – The Amsterdamsche Wisselbank (Amsterdam Exchange Bank) is founded.

- 1656 – The first European bank to use banknotes opens in Sweden for private clients; in 1668, it becomes a public bank.

- 1690s – The Massachusetts Bay Colony is the first of the Thirteen Colonies to issue permanently circulating banknotes.

- 1694 – The Bank of England is founded to provide money to the English King.

- 1695 – The Parliament of Scotland creates the Bank of Scotland.

- 1716 – John Law opens Banque Générale in France.

- 1717 – Master of the Royal Mint Sir Isaac Newton sets a new ratio between silver and gold, which leads to Britain using a gold standard.

- 1720 – The South Sea Bubble and John Law's Mississippi Scheme failure cause a European financial crisis and force many bankers out of business.

- 1775 – The first building society, Ketley's Building Society, is established in Birmingham, England.

- 1782 – The Bank of North America opens.

- 1791 – The First Bank of the United States is chartered by the United States Congress for 20 years.

- 1800 – The Rothschild family establishes European-wide banking.

- 1800 – Napoleon Bonaparte founds the Bank of France on January 18.

- 1811 – The Senate votes against renewing the charter of the First Bank of the United States, and the bank is dissolved.

- 1816 – The Second Bank of the United States is chartered for 20 years, due to difficulties financing the government during and after the War of 1812.

- 1817 – The New York Stock Exchange Board is established.

- 1818 – The first savings bank of Paris is established.

- 1825 – Panic of 1825 in which 70 UK banks fail.

- 1862 – To finance the American Civil War, the US government under President Abraham Lincoln issues paper money called "greenbacks."

- 1874 – The Specie Payment Resumption Act is passed, allowing US paper currency to be exchanged for gold starting in 1879.

- 1913 – The Federal Reserve Act creates the Federal Reserve System, the central banking system of the United States, and gives it the power to issue legal money.

- 1930–33 – After the Wall Street Crash of 1929, 9,000 banks close, wiping out one-third of the money supply in the United States.

- 1933 – Executive Order 6102 signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt forbids US citizens from owning gold coin, gold bullion, and gold certificates beyond a certain amount, ending the ability to exchange US dollars for gold.

- 1971 – The Nixon Shock is a series of economic actions by President Richard Nixon that end the direct exchange of US dollars for gold by foreign nations. This effectively ends the Bretton Woods system of international finance.

- 1986 – The "Big Bang" (loosening of London financial market rules) helps confirm London's place as a global banking center.

- 2007 – Start of the Late-2000s financial crisis that leads to a credit crunch and the failure and bail-out of many of the world's biggest banks.

- 2008 – Washington Mutual collapses, the largest bank failure in US history at that time.

Images for kids

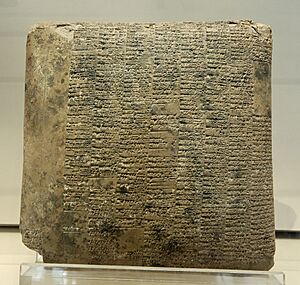

-

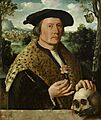

Among many other things, the Code of Hammurabi recorded interest-bearing loans.

-

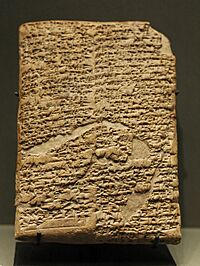

Christ drives the Usurers out of the Temple, a woodcut by Lucas Cranach the Elder in Passionary of Christ and Antichrist

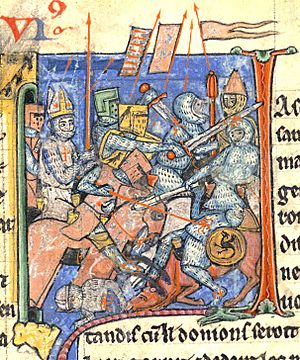

-

Adhemar de Monteil in chain mail carrying the Holy Lance in one of the battles of the First Crusade

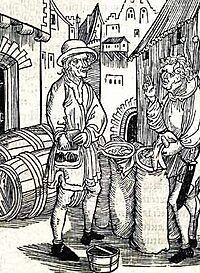

-

Of Usury, from Brant's Stultifera Navis (the Ship of Fools); woodcut attributed to Albrecht Dürer

-

The old town hall in Amsterdam where the Bank of Amsterdam was founded in 1609, painting by Pieter Saenredam

-

The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 was handled by Francis Baring and Company of London.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la banca para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la banca para niños

- Money creation

- Monetary reform

- History of money

- Banker (ancient)

- Branchless banking

- History of the cheque

- Early Canadian banking system

- History of banking in the United States

- Global financial system

- History of Virtual Cryptobanking with Bitcoin

- List of recessions

- Online banking

- Open banking

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |