History of Maryland facts for kids

The history of Maryland began when Europeans first explored the area in 1498 with John Cabot. The first European settlements were made in 1634 by the English. Maryland was special because it offered religious freedom, especially for Catholics. Like other colonies around the Chesapeake Bay, its economy relied on tobacco. This crop was mostly grown by enslaved Africans, though many young people from Britain also came as indentured servants in the early years.

In 1778, during the American Revolution, Maryland became the seventh state in the United States. After the war, many plantation owners freed their enslaved people as the economy changed. Baltimore grew into one of the largest cities on the East Coast. Even though Maryland was a slave state in 1860, almost half of its African American population was already free. This was mainly due to people being freed after the American Revolution. Maryland was one of the "border states" that stayed with the Union during the American Civil War.

Contents

- Ancient History: Maryland's First People

- Early European Explorers Reach Maryland

- Colonial Maryland: A New Beginning

- Maryland and the American Revolution

- Maryland from 1789 to 1849

- Economic Growth and Transportation

- Maryland in the Civil War

- Maryland from 1865 to 1920

- Maryland in the 20th Century

- Images for kids

Ancient History: Maryland's First People

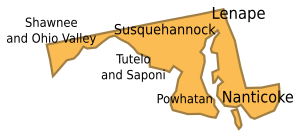

The first humans arrived in what is now Maryland around 10,000 BC, when the last ice age was ending. They were hunter-gatherers who moved around in small groups. They learned to adapt as the environment changed. They developed spears to hunt smaller animals like deer. By 1500 BC, oysters became an important food source.

As more food became available, Native American villages started to appear. Their communities became more complex. Around 1000 BC, they began making pottery. Later, when agriculture started, more permanent villages were built. But even with farming, hunting and fishing remained important ways to get food. The bow and arrow were first used for hunting in the area around 800 AD.

By 1000 AD, about 8,000 Native Americans lived in the area. They all spoke Algonquian languages and lived in 40 different villages. Many tribes lived along the Potomac River, including the Piscataway tribes. The area where the Nacotchtank lived is now Washington, D.C.. On the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay, tribes like the Nanticoke lived.

When Europeans began settling in Maryland in the early 1600s, new European diseases caused many Native Americans to die. They had no natural protection against these illnesses. This caused great disruption to their communities.

Early European Explorers Reach Maryland

In 1498, the first European explorers sailed along the Eastern Shore, near what is now Worcester County. In 1524, Giovanni da Verrazzano, sailing for France, passed the mouth of Chesapeake Bay. In 1608, John Smith entered the bay and explored it widely. His maps still exist today. Even though they were made with old tools, they are surprisingly accurate.

Colonial Maryland: A New Beginning

George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore, asked King Charles I for a special paper called a royal charter to create a colony. After Calvert died in 1632, the charter for "Maryland Colony" was given to his son, Cecilius Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore, on June 20, 1632. Some historians believe this was a way to make up for his father losing his job after he became Roman Catholic.

The colony was officially named in honor of Queen Henrietta Maria, the wife of King Charles I. Some Catholic scholars think it was named after Mary, the mother of Jesus, by George Calvert. The original charter used the Latin name Terra Mariae, which means "Mary's Land."

Maryland used a system called "headright" to encourage people to bring new settlers. The first settlers left England on November 22, 1633, led by Leonard Calvert, Cecil Calvert's younger brother. They sailed on two small ships, the Ark and the Dove. They landed on March 25, 1634, at St. Clement's Island in southern Maryland. This day is celebrated as Maryland Day each year. This was also the site of the first Catholic mass in the colonies, led by Father Andrew White. The first group included 17 gentlemen and their wives, and about 200 other people, mostly indentured servants.

After buying land from the Yaocomico Indians, they founded the town of St. Mary's. Leonard tried to rule the colony like a feudal lord, but people resisted. In 1635, he called for a colonial assembly. By 1638, the Assembly made him govern according to English laws. The Assembly then gained the power to create laws.

In 1638, Calvert took over a trading post on Kent Island that belonged to William Claiborne from Virginia. In 1644, Claiborne led an uprising of Maryland Protestants. Calvert had to escape to Virginia. But he returned with an armed group in 1646 and took back control.

Maryland soon became one of the few English colonies in North America where Catholics were a large group. Maryland was also a place where the English government sent thousands of convicts as punishment. This continued until the Revolutionary War.

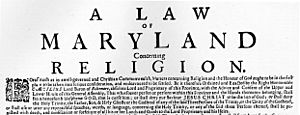

The Maryland Toleration Act, passed in 1649, was one of the first laws to clearly state that different types of Christianity would be tolerated.

The first capital, St. Mary's City, was designed to show the founders' beliefs. The city had a mayor's home in the center. Streets formed two triangles. One triangle pointed to the west, where the first state house and a jail were located. The other triangle pointed north, with a Catholic church and a school at its points. This design showed a clear separation of church and state, highlighting the importance of religious freedom.

St. Mary's City was the government's home until 1695. In 1642, a group of Puritans from Virginia, where Anglicanism was the official religion, moved to Maryland. They founded Providence, which is now called Annapolis.

In 1650, the Puritans rebelled against the government. They set up a new government that banned both Catholicism and Anglicanism. In March 1655, Lord Baltimore sent an army led by Governor William Stone to stop the revolt. Near Annapolis, his Catholic army was defeated by a Puritan army in the Battle of the Severn. The Puritan revolt lasted until 1658, when the Calvert family regained control and brought back the Toleration Act.

During the Puritan rule, Maryland Catholics were treated badly. Mobs burned down all the original Catholic churches in southern Maryland. In 1708, the government moved to Providence, which was renamed Annapolis in honor of Queen Anne. St. Mary's City is now an archaeological site with a small tourist center.

City Planning in Annapolis

Just as St. Mary's City showed the founders' ideas, the city plan of Annapolis showed the ideas of those in power in the early 1700s. Annapolis was designed with two circles in the city center. One circle included the State House, and the other had the Anglican St. Anne's Church. This design showed a stronger connection between church and state, and a government that was more aligned with Protestant churches.

The Mason–Dixon Line: Marking Boundaries

An old map was incorrect, and the original royal charter gave Maryland land that would have included Philadelphia, a major city in Pennsylvania. To solve this problem, the Calvert family (who controlled Maryland) and the Penn family (who controlled Pennsylvania) hired two surveyors, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, in 1750.

They surveyed what became known as the Mason–Dixon Line. This line became the border between the two colonies. The symbols of the Penn and Calvert families were placed along the line to mark it.

Horse Racing: A Popular Pastime

In the Chesapeake colonies (Virginia and Maryland), sports were very important to everyone. Wealthy plantation owners sponsored horse races, which attracted farmers who came to watch and bet. Some enslaved people became skilled horse trainers. Horse racing was especially important for the wealthy class. It was a big public event where they showed off their high social status through expensive horse breeding, training, and betting. Winning races was very important to them.

Maryland and the American Revolution

At first, Maryland did not want to separate from Great Britain. Its representatives in the Continental Congress were told to vote against independence. During the early part of the Revolutionary period, Maryland was governed by the Assembly of Freemen, which was a meeting of representatives from the state's counties.

The Assembly decided that this temporary government was not good enough. They needed a more permanent government. So, on July 3, 1776, they decided to elect a new group to write their first state constitution. This constitution would not mention the king or parliament, but would be a government "of the people only." On August 1, all free men who owned property elected representatives for this last meeting. This meeting was also called the Constitutional Convention of 1776. They wrote a constitution, and when they finished on November 11, they did not meet again. The new state government, created by the Maryland Constitution of 1776, took over. Thomas Johnson became Maryland's first elected governor.

On March 1, 1781, the Articles of Confederation officially began after Maryland approved them. The Articles had been sent to the states in 1777, but it took several years to approve them because of a fight over land claims in the west. Maryland was the last state to agree. It refused to approve the Articles until Virginia and New York gave up their claims to lands in what became the Northwest Territory.

No major battles of the American Revolutionary War happened in Maryland. However, Maryland soldiers fought bravely. General George Washington was very impressed with the Maryland soldiers (called the "Maryland Line") who fought in the Continental Army. Because of this, he supposedly gave Maryland the nickname "Old Line State." Today, the Old Line State is one of Maryland's two official nicknames.

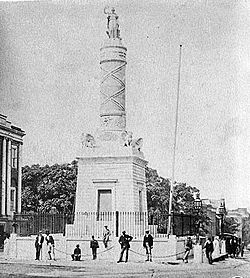

Maryland also played other roles during the war. For example, the Continental Congress met briefly in Baltimore from December 20, 1776, to March 4, 1777. Also, a Marylander, John Hanson, served as President of the Continental Congress from 1781 to 1782. Hanson was the first person to serve a full term as President of the Congress under the Articles of Confederation.

From November 26, 1783, to June 3, 1784, Annapolis served as the United States capital. The Confederation Congress met in the Maryland State House. (Annapolis was considered to be the new nation's permanent capital before Washington, D.C. was built). It was in the old senate chamber that George Washington famously resigned his role as commander in chief of the Continental Army on December 23, 1783. It was also there that the Treaty of Paris, which ended the Revolutionary War, was approved by Congress on January 14, 1784.

Maryland from 1789 to 1849

Quasi-War with France

After the Revolution, the U.S. Congress decided to build six frigates to start the United States Navy. One of the first three ships was built in Baltimore's shipyards and was named USS Constellation.

The Constellation was the first official U.S. Navy ship to sail. It was quickly sent to the Caribbean to protect U.S. interests against the French. During the Quasi-War, the Constellation, led by Captain Thomas Truxtun, fought two major naval battles against French ships. It won both battles and became the first American ship to capture an enemy vessel. Its return to Baltimore was met with great celebration. The Constellation's speed and power earned it the nickname "Yankee Racehorse" from the French.

The War of 1812: Maryland Under Attack

During the War of 1812, the British attacked cities along the Chesapeake Bay, including Havre de Grace. Two important battles happened in Maryland. The first was the Battle of Bladensburg on August 24, 1814, near Washington, D.C.. The American soldiers defending the city were defeated. After winning at Bladensburg, the British captured Washington, D.C. They burned and looted important public buildings, forcing President James Madison to flee.

The British then marched to Baltimore, hoping to deliver a final blow. Baltimore was a busy port, and the British believed it hid many privateers who were attacking British ships. The city's defenses were led by Major General Samuel Smith, a Maryland militia officer and U.S. senator. Baltimore was well-fortified with supplies and about 15,000 troops. Maryland militia fought bravely at the Battle of North Point. During this battle, a Maryland sharpshooter killed the British commander, General Robert Ross. This battle gave Baltimore enough time to strengthen its defenses.

After reaching the edge of the American defenses, the British stopped their advance and pulled back. With the land attack failing, the sea battle became pointless, and the British retreated.

At Fort McHenry, about 1,000 soldiers led by Major George Armistead waited for the British navy to attack. To help their defense, American merchant ships were sunk at the entrance to Baltimore Harbor to block British ships. The attack began on the morning of September 13, as the British fleet of about 19 ships began firing rockets and mortar shells at the fort. After an initial exchange of fire, the British fleet moved out of range of Fort McHenry's cannons. For the next 25 hours, they bombarded the outnumbered Americans. On the morning of September 14, a very large American flag was raised over Fort McHenry. The British knew they had not won. The bombing of the fort inspired Francis Scott Key, from Frederick, Maryland, to write "The Star-Spangled Banner" as he watched the attack. It later became the country's national anthem.

Economic Growth and Transportation

The American Revolution increased the demand for wheat and iron ore, leading to more flour mills in Baltimore. Transporting iron ore greatly helped the local economy. The British naval blockade during the War of 1812 hurt Baltimore's shipping. But it also freed merchants from British debts, which, along with capturing British ships, helped the city grow. By 1800, Baltimore was one of the new nation's major cities.

New Ways to Travel: Canals and Railroads

Baltimore had a deepwater port. In the early 1800s, many business leaders in Maryland looked to the western frontier for economic growth. The challenge was finding a reliable way to transport goods and people. The National Road and private turnpikes were being built across the state, but more routes were needed. After the success of the Erie Canal (built 1817–25), Maryland leaders also planned canals. After some canal projects failed near Washington, D.C., the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (C&O) began construction there in 1828. Baltimore businesses saw this as a threat. Building a similar canal west from Baltimore was difficult due to the land. But the idea of building railroads started to gain support in the 1820s.

In 1827, city leaders got permission from the Maryland General Assembly to build a railroad to the Ohio River. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) became the first chartered railroad in the United States. It opened its first section of track in 1830, between Baltimore and Ellicott City. It was the first company to use a steam locomotive built in America, called the Tom Thumb. The B&O built a branch line to Washington, D.C. in 1835. The main line west reached Cumberland in 1842, eight years before the C&O Canal. The railroad continued building westward. In 1852, it became the first rail line to connect the Ohio River to the East Coast. Other railroads were built in and through Baltimore by the mid-1800s, including the Northern Central; the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore; and the Baltimore and Potomac.

The Industrial Revolution in Maryland

Baltimore's seaport and good railroad connections helped it grow a lot during the Industrial Revolution in the 1800s. Many factories and businesses were started in Baltimore and the surrounding area after the Civil War.

Cumberland was Maryland's second largest city in the 1800s. It had plenty of coal, iron ore, and timber nearby. These resources, along with railroads, the National Road, and the C&O Canal, helped it grow. The city became a major manufacturing center, with industries making glass, beer, fabrics, and tinplate.

The Pennsylvania Steel Company started a steel mill at Sparrow's Point in Baltimore in 1887. Bethlehem Steel bought the mill in 1916. By the mid-1900s, it became the world's largest steel mill, employing tens of thousands of workers.

Education in Maryland

In 1807, the College of Medicine of Maryland became the seventh medical school in the United States. (It was later renamed the University of Maryland Medical School).

In 1840, the non-religious St. Mary's Female Seminary was founded in St. Mary's City by order of the Maryland state legislature. This school later became St. Mary's College of Maryland, the state's public honors college. The United States Naval Academy was founded in Annapolis in 1845. The Maryland Agricultural College was started in 1856, and it eventually grew into the University of Maryland.

Immigration and Religious Changes

After anti-Catholic laws were removed in the early 1830s, the Catholic population began to grow significantly. This growth was boosted by large waves of Irish Catholic immigration due to the Great Potato Famine in Ireland (1845–49). It continued through the first half of the 1900s with Italian immigration and Polish immigrations. Baltimore was the third largest entry point for European immigrants on the East Coast during much of this time. Even with this increase, the Catholic population has never become the majority in the state.

Maryland in the Civil War

See also: American Civil War and History of slavery in Maryland

Maryland's Divided Loyalties

Maryland was one of the border states, located between the North and South. Like in Virginia and Delaware, some plantation owners in Maryland had freed their enslaved people in the 20 years after the Revolutionary War. By 1860, almost half (49.1%) of the African Americans in Maryland were free.

After John Brown's raid in 1859 on Harper's Ferry, some citizens in slaveholding areas started forming local militias for defense. Out of a population of 687,000 in 1860, about 60,000 men joined the Union army, and about 25,000 fought for the Confederacy. People's political choices often matched their economic interests. Slave owners and those who traded with the South usually supported the Confederacy. Small farmers and merchants outside major cities and in western Maryland sided with the Union.

The first bloodshed of the Civil War happened in Baltimore. Massachusetts troops were fired upon while marching between train stations on April 19, 1861. After this, Baltimore Mayor George William Brown and others asked Maryland Governor Thomas H. Hicks to burn railroad bridges and cut telegraph lines leading to Baltimore. This was to stop more troops from entering the state. Governor Hicks reportedly agreed to this plan.

Maryland remained part of the Union during the Civil War. President Abraham Lincoln's strong actions to stop violence and disagreement in Maryland, along with Governor Hicks's help, were important. Hicks worked with federal officials to prevent more violence. As an example of the state's divided loyalties, Lincoln received only one vote in Prince George's County in the 1860 election. This county was a center for large plantations.

Lincoln promised to avoid having Northern soldiers march through Baltimore while protecting the endangered U.S. Capital. Most forces had to take a slow boat route. Massachusetts militia General Benjamin F. Butler used the water route after hearing about the troubles in Baltimore. He took a ferryboat and sailed down the Chesapeake Bay to anchor near the Naval Academy in Annapolis.

He landed his troops from Massachusetts, New York, and Rhode Island, despite protests from Governor Thomas Holliday Hicks. He put some soldiers on the old Navy training ship, the frigate USS Constitution, and moved it offshore to protect it. Butler's soldiers, including some railroad workers, found a small train engine. They used it to take cars full of soldiers up the Annapolis Line of the B&O Railroad to Relay Junction. From there, they could go west to Harpers Ferry, West Virginia or south to Washington. Northern regiments used this route to reach the train station near the U.S. Capitol. They camped that evening in the Capitol Rotunda, which was not yet finished. Another unit was sent to reinforce the White House, where the President greeted them with relief.

Marylanders who supported the South easily crossed the Potomac River to join and fight for the Confederacy. These exiles formed a "Maryland Line" in the Army of Northern Virginia. This group included one infantry regiment, one infantry battalion, two cavalry battalions, and four artillery battalions. Records show that up to 25,000 Marylanders went south to fight for the Confederacy. About 60,000 Maryland men served in all parts of the Union military. Many Union troops were said to join with the promise of staying in Maryland.

To prevent an uprising in Baltimore, a Union artillery group was placed on Federal Hill. They had orders to destroy the city if Southern supporters took control. After the Baltimore riot of 1861, Union troops under General Benjamin F. Butler occupied the hill in the middle of the night. This was against orders from Washington. Butler and his men built a small fort with cannons pointed toward the city center. Their goal was to ensure the city and state of Maryland remained loyal to the federal government, even if it meant using force. This fort and the Union occupation lasted throughout the Civil War. Today, a large flag, a few cannons, and a small monument remain on the hill to remember this time.

Because Maryland stayed in the Union, it was not included in the Emancipation Proclamation. A special meeting was held in 1864, which led to a new state constitution being passed on November 1 of that year. Article 24 of this document outlawed slavery. A campaign by state politician John Pendleton Kennedy and others ensured that slavery would be abolished in the new document. This issue was strongly debated for almost a year across the state. In the end, the elimination of slavery was approved by only about 1,000 votes. The right to vote was given to non-white males in the Maryland Constitution of 1867, which is still in use today.

During this time, the USS Constellation was the main ship of the U.S. Africa Squadron from 1859 to 1861. During this period, it stopped the African slave trade by capturing three slave ships and freeing the enslaved people. The last ship was captured at the start of the Civil War. The Constellation spent much of the war preventing Confederate ships from attacking trade in the Mediterranean Sea.

The Civil War on Maryland Soil

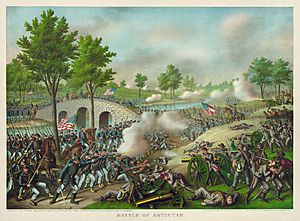

The largest and most important battle fought in Maryland was the Battle of Antietam. It took place on September 17, 1862, near Sharpsburg. This battle was the end of Robert E. Lee's Maryland Campaign. Lee hoped to get new supplies, recruit more men from Maryland (where many people supported the Confederacy), and influence public opinion in the North. With these goals, Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, with about 40,000 men, had entered Maryland after their recent victory at Second Bull Run.

While Major General George B. McClellan's 87,000-man Army of the Potomac was moving to stop Lee, a Union soldier found a lost copy of Lee's detailed battle plans. The order showed that Lee had divided his army and spread parts of it out (to Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, and Hagerstown, Maryland). This meant each part could be isolated and defeated if McClellan moved quickly enough. McClellan waited about 18 hours before deciding to use this information. This delay cost him a great chance to defeat Lee completely.

The armies met near Sharpsburg by Antietam Creek. Even though McClellan arrived on September 16, his usual caution delayed his attack on Lee. This gave the Confederates more time to prepare their defenses. It also allowed parts of Lee's army to arrive from other locations. McClellan had twice as many soldiers, but his lack of coordination meant Lee could move his defenders to stop each attack.

Even though the Battle of Antietam was a tactical draw (meaning neither side clearly won on the battlefield), it was seen as a strategic Union victory and a turning point of the war. It forced Lee's invasion of the North to end. It was also a big enough victory for President Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which took effect on January 1, 1863. His advisors had told him to announce it after a Union victory, so it wouldn't look like he was acting out of desperation. The Union's win at Antietam may also have stopped the governments of France and Great Britain from recognizing the Confederacy. Some believed they might have done so if the Union had lost again.

During the war, Maryland's naval ship, the relatively new sloop-of-war USS Constellation, continued its duty of stopping slave ships for the Union Navy. Stationed in the Mediterranean, the Constellation actively protected convoys and defended against ships attacking trade.

Maryland from 1865 to 1920

H. L. Mencken (1880–1956) was a famous writer and thinker from Maryland. In 1922, he praised the state for its "singular and various beauty from the stately estuaries of the Chesapeake to the peaks of the Blue Ridge." He noted that Maryland seemed to be in the middle for many things, like population and the number of Catholics. He felt that Maryland was a good example for other states.

After the Civil War: Political Changes

Since Maryland stayed in the Union during the Civil War, it was not part of the Reconstruction Act that applied to the former Confederate states. However, it had been a slave state. By 1860, almost half of its Black population was free. After the war, many white Maryland residents tried to regain control over freedmen (formerly enslaved people) and free Black people. Racial tensions increased. There were also deep divisions in the state between those who fought for the North and those who fought for the South.

In the late 1860s, white members of the Democratic Party quickly regained power in the state. They replaced Republicans who had been elected during the war. Support for the 1864 Constitution ended. Democrats replaced it with the Maryland Constitution of 1867. This document, still in use today, was more like the 1851 constitution. It allowed for the legislature to be based on population, not counties. This gave more political power to cities and, by extension, to freedmen. However, the new constitution took away some protections for African Americans that were in the 1864 document.

In 1896, a group of Republicans and Black voters helped elect Lloyd Lowndes, Jr. as governor. Some Republican congressmen were also elected after a period of Democratic control. Over the next few decades, African Americans faced discrimination. The Democratic-controlled legislature tried to pass laws in 1905, 1907, and 1911 to prevent Black people from voting. But these attempts failed, largely because of strong opposition from Black citizens and their growing influence. Black people made up 20% of the voters and had established themselves in several cities, where they had more security. Also, immigrants made up 15% of the voting population and opposed these measures. The legislature found it hard to create rules against Black people that would not also harm immigrants.

In 1910, the legislature proposed the Digges Amendment to the state constitution. This amendment would have used property requirements to effectively stop many African Americans and poor white people (including new immigrants) from voting. This technique was used by other southern states from 1890 to 1910. The Maryland General Assembly passed the bill, which Governor Austin Lane Crothers supported. Before the measure went to a public vote, another bill was proposed that would have made the Digges Amendment's requirements into law. Because of widespread public opposition, that measure failed, and the amendment was also rejected by Maryland voters.

Maryland citizens achieved the most notable rejection of a law designed to stop Black people from voting in the nation. Similar measures had been proposed in Maryland before but also failed (the Poe Amendment in 1905 and the Straus Amendment in 1909). The power of Black people at the ballot box and in the economy helped them resist these bills and efforts to take away their voting rights.

Businessmen like Johns Hopkins, Enoch Pratt, George Peabody, and Henry Walters were generous people in 19th-century Baltimore. They founded important educational, health care, and cultural institutions in the city. These include a university, a free city library, a music and art school, and an art museum, all named after them.

Progressive Era Reforms

In the early 1900s, a political reform movement began, led by the growing middle class. One of their main goals was to have government jobs given based on skill rather than political favors. Other changes aimed to reduce the power of political bosses and machines, which they succeeded in doing.

Through a series of laws passed between 1892 and 1908, reformers pushed for standard state-issued ballots (instead of those given out by political parties). They also got closed voting booths to prevent party workers from "helping" voters. They started primary elections to stop party bosses from choosing candidates. And they had candidates listed without party symbols, which made it harder for people who could not read to vote. While these were called democratic reforms, they also had other results desired by the middle class. They discouraged people from lower classes and those who could not read from voting. Voting participation dropped from about 82% of eligible voters in the 1890s to about 49% in the 1920s.

Other laws regulated working conditions. For example, in laws passed in 1902, the state regulated conditions in mines. It outlawed child labor for children under 12, made school attendance required, and passed the nation's first workers' compensation law.

The debate over prohibition of alcohol, another reform, led to Maryland's second nickname. A newspaper jokingly called Maryland "the Free State" because it allowed alcohol.

The Great Baltimore Fire

The Great Baltimore Fire of 1904 was a huge event for Baltimore and the entire state. The fire burned in Baltimore from Sunday, February 7, at 10:48 a.m., to Monday, February 8, at 5:00 p.m. More than 1,231 firefighters worked to control the blaze.

One reason the fire lasted so long was the lack of national standards for fire-fighting equipment. Fire engines from nearby cities (like Philadelphia and Washington, as well as units from New York, Wilmington, and Atlantic City) came to help. But many were useless because their hoses did not fit Baltimore hydrants. As a result, the fire burned for over 30 hours, destroying 1,526 buildings and covering 70 city blocks.

After the fire, 35,000 people lost their jobs. The city was rebuilt using more fireproof materials, such as granite pavers.

Maryland During World War I

Entry into World War I brought changes to Maryland.

Maryland became the site of new military bases, such as Camp Meade (now Fort Meade) and the Aberdeen Proving Ground, both started in 1917. The Edgewood Arsenal was founded the next year. Other existing facilities, like Fort McHenry, were greatly expanded.

To organize wartime activities, the General Assembly created a Council of Defense. This Council had a large budget and was in charge of defending the state, overseeing the draft, controlling wages and prices, providing housing for war-related industries, and promoting support for the war. Citizens were encouraged to grow their own victory gardens and follow rationing rules. They were also required to work, after the legislature passed a compulsory labor law.

Maryland in the 20th Century

The Ritchie Administration

In 1918, Maryland elected Albert C. Ritchie, a Democrat, as governor. He was reelected four times, serving from 1919 to 1934. He is considered the state's most popular governor ever. Ritchie was very supportive of businesses. He hired a company to make government operations more efficient and created a budget process controlled by economists. He also got approval for a civil service system, which reformers had wanted for a long time. This system meant jobs were given based on merit, not political favors. He also reduced the number of state elections by making legislative terms longer (from two to four years). He appointed many citizen groups to advise on almost every part of government. State property taxes dropped sharply under Ritchie, but so did state services. A powerful state movie censorship board kept ideas they considered "subversive" away from the public. Three times, including 1924 and 1932, Ritchie was a candidate for President of the United States. He argued that Presidents Coolidge and Hoover spent too much money. Ritchie lost his bid for the Democratic Party's nomination for President in 1932. Despite a large show of support at the convention, Franklin D. Roosevelt was nominated and won the election. Ritchie continued to serve as governor until 1935.

The Great Depression and World War II

Maryland's cities and rural areas experienced the Great Depression differently. In 1932, the "Bonus Army" marched through the state on its way to Washington, D.C.. Besides President Roosevelt's nationwide New Deal reforms, which put men to work building roads and parks, Maryland also took steps to get through the hard times. For example, in 1937, the state started its first ever income tax to raise money for schools and welfare.

The state made some progress in civil rights. In 1935, the case Murray v. Pearson et al. resulted in a Baltimore City Court ordering the integration of the University of Maryland Law School. The student in that case was represented by Thurgood Marshall, a young lawyer with the NAACP and a native of Baltimore. When the state attorney general appealed, the Court of Appeals upheld the decision.

Because the state did not appeal the ruling in federal courts, this state ruling was the first to challenge Plessy v. Ferguson, the 1896 Supreme Court decision that allowed "separate but equal" facilities. While the ruling was an important moral step, it only applied within Maryland.

A hurricane in 1933 created an inlet in Sinepuxent Bay at Ocean City. This made the small town attractive for recreational fishing. During World War II, more large defense facilities were built in the state, such as Andrews Air Force Base, Patuxent River Naval Air Station, and the large Glenn L. Martin aircraft factory east of Baltimore.

In 1952, the eastern and western parts of Maryland were connected for the first time by the long Chesapeake Bay Bridge. This bridge (and its later, parallel span) increased tourist traffic to Ocean City, which then experienced a building boom. Soon after, the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel allowed long-distance drivers to bypass downtown Baltimore. The earlier Harry W. Nice Memorial Bridge allowed them to bypass Washington, D.C. Two beltways, I-695 and I-495, were built around Baltimore and Washington. I-70, I-270, and later I-68 connected central Maryland with western Maryland. I-97 linked Baltimore with Annapolis. Passenger and freight steamboat transportation, once very important throughout the Chesapeake Bay, ended in the mid-1900s.

In 1980, the opening of Harborplace and the Baltimore Aquarium made that city a major tourist spot. Charles Center, the World Trade Center, and the popular Camden Yards baseball stadium were built downtown. Fells Point also became popular. The historic Annapolis waterfront area, once a working fishing port, also saw changes. The Metro Subway and the north-south Baltimore Light Rail system were built.

Besides general suburban growth, new planned communities appeared. The most notable was Columbia, but also Montgomery Village, Belair at Bowie, St. Charles, Cross Keys, and Joppatowne. Many shopping malls were built, with the state's three largest being Annapolis Mall, Arundel Mills, and the Towson Town Center. Community colleges were established in almost every county in Maryland. Large, mechanized poultry farms became common on the lower Eastern Shore, along with irrigated vegetable farming. In Southern Maryland, tobacco farming had almost disappeared by the end of the century due to suburban housing development and a state program that paid farmers to stop growing tobacco. Industrial, railroad, and coal-mining jobs in the four westernmost counties declined. However, that area's economy was helped by more outdoor tourism and new technology jobs. In 2013, Maryland ended capital punishment in the state.

Images for kids

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |